Abstract

Background

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinases (MAPKKKs) are the important components of MAPK cascades, which play the crucial role in plant growth and development as well as in response to diverse stresses. Although this family has been systematically studied in many plant species, little is known about MAPKKK genes in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), especially those involved in the regulatory network of stress processes.

Results

In this study, we identified 155 wheat MAPKKK genes through a genome-wide search method based on the latest available wheat genome information, of which 29 belonged to MEKK, 11 to ZIK and 115 to Raf subfamily, respectively. Then, chromosome localization, gene structure and conserved protein motifs and phylogenetic relationship as well as regulatory network of these TaMAPKKKs were systematically investigated and results supported the prediction. Furthermore, a total of 11 homologous groups between A, B and D sub-genome and 24 duplication pairs among them were detected, which contributed to the expansion of wheat MAPKKK gene family. Finally, the expression profiles of these MAPKKKs during development and under different abiotic stresses were investigated using the RNA-seq data. Additionally, 10 tissue-specific and 4 salt-responsive TaMAPKKK genes were selected to validate their expression level through qRT-PCR analysis.

Conclusions

This study for the first time reported the genome organization, evolutionary features and expression profiles of the wheat MAPKKK gene family, which laid the foundation for further functional analysis of wheat MAPKKK genes, and contributed to better understanding the roles and regulatory mechanism of MAPKKKs in wheat.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-016-2993-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Wheat, MAPKKKs, Gene family, Expression profiles

Background

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades play the crucial role in plant growth and development as well as in response to stresses, which are highly conserved in the signal transduction pathway in eukaryote [1]. The MAPK pathway included three main protein kinase members, namely MAPK kinase kinases (MAPKKK or MEKK), MAPK kinases (MKK or MEK) and MAPKs (MPK). They achieved the function through sequentially being phosphorylated. Upstream signals firstly activated the MAPKKKs, which in turn the MAPKKKs activated the MAPKKs and then specific MAPKs were activated by the MAPKKs. Eventually, the activated MAPKs phosphorylated transcription factors, enzymes or other signaling components to modulate the expression of downstream genes to complete signal amplification [2, 3]. It has been demonstrated that MAPK cascades played a vital role in cell division, growth and differentiation [4, 5], hormone response [6], plant immunity [7, 8], biotic and abiotic stress response and so on [9–11]. To date, extensive studies have been conduct to systematically investigate the MAPKKK gene family in many plant species and it is reported that there were 74 putative MAPKKK genes in maize (Zea mays), 75 in rice (O. sativa), 78 in cotton (G. raimondii) and 80 in Arabidopsis (A. thalianna), respectively [12–15].

Wheat is one of the most important crops worldwide, occupying 17 % of cultivated lands and serving as the staple food source for 30 % of the human population all over the world [16, 17]. Genetically, wheat is an allohexaploid species (2n = 6x = 42), which has a complex original and evolutionary history, derived from three diploid donor species through two naturally interspecific hybridization events. The initial hybridization event was occurred between A genome donor (T. urartu, AA; 2n = 14) and B geome donor (Aegilops speltoides, SS; 2n = 14) to produce the allotetraploid (AABB, T. turgidum L) about 0.2 MYa ago, and then the AABB donor crossed with the D genome donor (A. Tauschii Coss) to form the allohexaploid wheat (AABBDD) about 9000 years ago [18]. As a result, wheat possesses a large and complex genome with three homologous genomes (A, B and D) and the size more than 17 Gb, which makes it a huge challenge to conduct genomic study in wheat. But, as the newly formed polyploidy, wheat is considered as an ideal model for chromosome interaction and polyploidization studies in plants [19, 20]. Recently, the draft genome sequencing of hexaploid wheat Chinese Spring (CS) was completed using the chromosome-based strategy, which laid the foundation to identify wheat gene family at the genome-level and also to discern the homologous copies in these three sub-genomes [17]. The retention and dispersion of homologous gene will provide the indispensable information about chromosome interaction during polyploidization [21, 22].

At present, no systematical investigation of MAPKKK gene family has been performed in wheat. In light of the functional significance of this family, an in silico genome-wide search was conducted to identify wheat MAPKKK gene family in this study. Then, the chromosome localization, gene structure, conserved protein domain, phylogenetic relationship as well as expression profiles and regulatory network were systematically analyzed in the putative wheat MAPKKK genes to reveal the evolutionary and functional features of these genes. Our study will provide a basis for further functional analysis of the wheat MAPKKK genes, and will contribute to better understanding the molecular mechanism of MAPKKKs involving in regulating growth and development as well as stress processes in wheat.

Methods

Identification of MAPKKK gene family in wheat

The wheat MAPKKK gene family was identified following the method as described by Rao et al with some modifications [13]. First, all the wheat protein sequences available were downloaded from the Ensemble database (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html) to construct a local protein database. Then, this database were searched with 304 known MAPKKK gene sequences collected from A.thaliana (80), O. sativa (75), Z. mays (74) and B.distachyon (75) using the local BLASTP program with an e-value of 1e-5 and identity of 50 % as the threshold. Furthermore, all the MAPKKK sequences were aligned and the obtained alignments were used to construct a HMM profile using the hmmbuild tool embedded in HMMER3.0 (http://hmmer.org/download.html), and then the HMM profile were used to search the local protein database using the hmmsearch tool. HMMER and BLAST hits were compared and parsed by manual editing. Furthermore, a self-blast of these sequences was performed to remove the redundancy and the remaining sequences were considered as the putative TaMAPKKK proteins, which then were submitted to the NCBI Batch CD-search database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi) and PFAM databases (http://pfam.xfam.org/) to confirm the presence and integrity of the kinase domain. Finally, all the obtained sequences were verified the existence by BLASTN similarity search against the wheat ESTs deposited in NCBI database. The theoretical pI (isoelectric point) and Mw (molecular weight) of the putative TaMAPKKK were calculated using compute pI/Mw tool online (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/). Subcellular localization of each TaMAPKKK cascade kinases were predicted using the TargetP software of the CBS database [23].

Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments were generated using ClustalW tool [24]. To investigate the evolutionary relationship among MAPKKK proteins, a neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed by MEGA 6.0 software based on the full-length of MAPKKK protein sequences [25]. Bootstrap test method was adopted and the replicate was set to 1000.

Gene structure construction, protein domain and motif analysis

The gene structure information were got from Ensemble plants database (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html) and displayed by Gene Structure Display Server program (GSDS: http:/gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/). The protein domains and motifs in the MAPKKKs were predicted using InterProScan against protein databases (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/). The schematic representing the structure of all members of TaMAPKKKs was based on the InterProScan analysis.

Chromosomal locations and gene duplication

Genes were mapped on chromosomes by identifying their chromosomal position provided in the wheat genome database. Gene duplication events of MAPKKK genes in wheat were investigated based on the following three criteria: (a) the alignment covered >80 % of the longer gene; (b) the aligned region had an identity >80 %; and (c) only one duplication event was counted for the tightly linked genes [12, 26]. In order to visualize the duplicated regions in the T. aestivum genome, lines were drawn between matching genes using Circos-0.67 program (http://circos.ca/).

Identification of cis-regulatory elements

To investigate the cis-regulatory elements, the upstream regions (2 kbp) of all wheat MAPKKK genes were extracted, which were considered as the proximal promoter regions for the individual wheat MPKKK genes. Then, all the sequences were submitted to PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Plantcare/html/) to identify the putative cis-acting regulatory elements.

Network interaction analysis

The interaction network which the TaMAPKKK genes involved were investigated based on the orthologous genes between Wheat and Arabidopsis using the AraNet V2 tool (http//www.inetbio.org/aranet/). Then, enrichment analysis was implemented by BiNGO, a cytoscape plugin, for gene ontology analysis and identifying processes and pathways of specific gene sets. Over-represented GO full categories were identified with a significance threshold of 0.01.

The MAPKKK gene expression analysis by RNA-seq data

To study the expression of TaMAPKKK genes in different organs and response to stress, transcriptome sequencing data obtained from WHEAT URGI (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/files/RNASeqWheat/) and NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database were used to investigate the differential expression of TaMAPKKKs. The accession numbers and sample information of the used data were listed in Additional file 1. TopHat and Cufflinks were used to analyze the genes’ expression based on the RNA-seq data [27]. The FPKM value (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped) was calculated for each MAPKKK gene, the log10-transformed (FPKM + 1) values of the 155 TaMAPKKK genes were used for heat map generation. And fold change cutoff of two and p-value < 0.05, q-value < 0.05 were taken as statistically significant threshold [28, 29].

Plant materials, growth conditions, and treatments

The plants of wheat cultivar ‘CS’ were reared in growth chambers at 23 ± 1 °C with a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark. The roots, stems, leaves, spikes (1 d before flowering), and grains (10d after pollination) were collected from flowering plants for tissue expression analysis. One-week-old seedlings which consisted with RNA-seq data were treated by 150 mM NaCl which represented salt treatment, and the seedlings grown under normal condition were used as control. The leaves of seedlings under salt and also control conditions were collected at 0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h after treatment. All the plant samples from two biological replicates were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately and stored at −80 °C for RNA isolation.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

The total RNA was extracted using Plant RNA Kit reagent (Omega Bio-Tek, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA integrity was checked by electrophoresis on 1.0 % agarosegels stained with ethidium bromide (EB). The first strand cDNAs were synthesized using a Vazyme Reverse Transcription System (Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR analyses were performed using the primer pairs listed in Additional file 2. Two biological and three technical replicates for each sample were obtained using the real-time PCR system (BIO-RAD CFX96, USA). The β-actin gene was used as internal reference for all the qRT–PCR analysis. Each treatment was repeated three times independently. The expression profile was calculated from the 2–△△CT value [ΔΔCT = (CTtarget/salt – CTactin/salt) – (CTtarget/control – CTactin/control)] [30].

Results and discussion

Genome-wide Identification of MAPKKK Family in Wheat

Availability of the genome sequence made it possible for the first time to identify all the MAPKKK family members in wheat. Using the method as described above, a total of 155 genes with the complete kinase domain were identified as the MAPKKK members in the wheat genome. Since there is no standard nomenclature, the predicted wheat MAPKKK genes were then designated as TaMAPKKK1 to TaMAPKKK155 based on the blast scores. It was notable that wheat possessed the largest MAPKKK gene family among the reported species (Table 1), which may be the result of its allohexaploid genome and complex evolutionary process.

Table 1.

Comparison of the gene abundance in three subfamilies of MAPKKK genes in different plant species

| Species | Raf | MEKK | ZIK | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 115 | 29 | 11 | 155 |

| Arabidopsis | 48 | 21 | 11 | 80 |

| Rice | 43 | 22 | 10 | 75 |

| Maize | 46 | 22 | 6 | 74 |

| Brachypodium | 45 | 24 | 6 | 75 |

| Tomato | 40 | 33 | 16 | 89 |

| soybean | 92 | 34 | 24 | 150 |

| Grapevine | 27 | 9 | 9 | 45 |

| Cucumber | 31 | 18 | 10 | 59 |

| Canola | 39 | 18 | 9 | 66 |

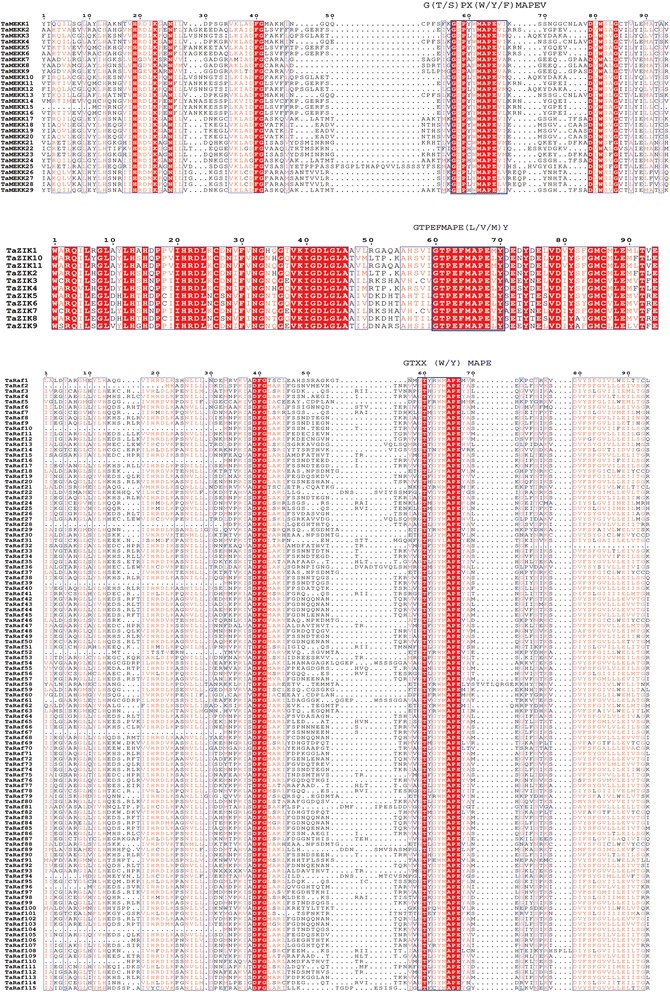

As reported in Arabidopsis and other plant species [12–15], the MAPKKK gene family could be subdivided into Raf, MEKK and ZIK subfamily according to the specific conserved signature motifs contained by these subfamilies, of which Raf had the signature of GTXX (W/Y) MAPE, ZIK of GTPEFMAPE (L/V) Y, and MEKK of G (T/S) PX (W/Y/F) MAPEV [15, 31]. To validate our prediction and subcategorize the identified wheat MAPKKKs, we further investigated the conserved signature motif in these TaMAPKKKs. Results showed that all the putative wheat MAPKKKs possessed at least one of the three conserved signature motifs (Fig. 1). Among them, 29 genes shared the conserved motif G (T/S) PX (W/Y/F) MAPEV, which were categorized into MEKK subfamily, and 11 had the motif GTPEFMAPE (L/V)Y, belonging to ZIK subfamily as well as the remaining 115 genes shared the motif GTXX (W/Y) MAPE, belonging to Raf subfamily. Then, we further named these gene based on the subfamily categories (Table 2). Moreover, the Raf subfamily is found to be the largest subfamily while the ZIK subfamily had the least members in wheat, which was consistent with the composition of MAPKKK genes in other species.

Fig. 1.

Protein sequence alignment of TaMAPKKK genes by ClustalW. The highlighted blue boxes showed the conserved signature motif

Table 2.

Characteristics of the putative wheat MAPKKK genes

| No. | MAPKKKs | Ensemble Wheat Gene ID | Subfamily | Subfamily Gene ID | Amino acid length | EST count | PI | MW (kDa) | Subcellular location | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TaMAPKKK1 | Traes_2BL_23D01E7F4 | MEKK | TaMEKK1 | 174 | 1 | 8.46 | 19.5 | Extracellular PlasmaMembrane | scaffold_2BL_6949321:447-1269 |

| 2 | TaMAPKKK2 | Traes_4DS_63F7CF3CE | TaMEKK2 | 424 | 17 | 5.46 | 47.7 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_4DS_2304216:3-2906 | |

| 3 | TaMAPKKK3 | Traes_4BL_A7AE389EE | TaMEKK3 | 654 | 20 | 6.33 | 72.0 | Nuclear | scaffold_4BL_6901486:6-5409 | |

| 4 | TaMAPKKK4 | Traes_6BL_93505FEAF | TaMEKK4 | 186 | 0 | 6.95 | 20.8 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_6BL_4252290:2480-4222 | |

| 5 | TaMAPKKK5 | Traes_2AS_6DA49285E | TaMEKK5 | 424 | 95 | 5.95 | 48.2 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_2AS_5236692:1-3092 | |

| 6 | TaMAPKKK6 | Traes_4BS_E01B5DAC9 | TaMEKK6 | 398 | 18 | 5.94 | 44.9 | Cytoplasmic | 4B:9539577-9542587 | |

| 7 | TaMAPKKK7 | TRAES3BF169900020CFD_g | TaMEKK7 | 473 | 4 | 4.64 | 49.8 | Chloroplast | 3B:24030208-24031629 | |

| 8 | TaMAPKKK8 | TRAES3BF036800120CFD_g | TaMEKK8 | 431 | 1 | 5.13 | 46.1 | Cytoplasmic Chloroplast | 3B:452802187-452803479 | |

| 9 | TaMAPKKK9 | TRAES3BF036800100CFD_g | TaMEKK9 | 366 | 5 | 4.55 | 38.2 | Cytoplasmic Chloroplast | 3B:452828028-452829181 | |

| 10 | TaMAPKKK10 | Traes_4DL_94E10E6EB | TaMEKK10 | 659 | 21 | 6.44 | 72.5 | Nuclear | 4D:19445439-19451009 | |

| 11 | TaMAPKKK11 | Traes_5DL_ADFFAE33D | TaMEKK11 | 450 | 36 | 5.84 | 51.1 | Cytoplasmic | 5D:146319049-146323269 | |

| 12 | TaMAPKKK12 | Traes_4AS_DF85CBD39 | TaMEKK12 | 710 | 21 | 6.55 | 77.7 | Nuclear | 4A:60064569-60070396 | |

| 13 | TaMAPKKK13 | Traes_6AL_E854742BB | TaMEKK13 | 186 | 0 | 7.67 | 20.8 | Cytoplasmic Extracellular | 6A:166723325-166725190 | |

| 14 | TaMAPKKK14 | Traes_5AS_9A8A9187C | TaMEKK14 | 404 | 22 | 5.32 | 45.9 | Cytoplasmic | 5A:52959512-52965983 | |

| 15 | TaMAPKKK15 | Traes_5AL_DEDF36AD2 | TaMEKK15 | 355 | 29 | 5.86 | 40.5 | Cytoplasmic | 5A:127609658-127614056 | |

| 16 | TaMAPKKK16 | Traes_5BL_35A6B4387 | TaMEKK16 | 557 | 29 | 5.95 | 62.7 | Cytoplasmic | 5B:250599335-250602791 | |

| 17 | TaMAPKKK17 | Traes_5AL_4D0919BA1 | TaMEKK17 | 549 | 9 | 5.7 | 60.9 | Nuclear | scaffold_5AL_2767817:3993-8685 | |

| 18 | TaMAPKKK18 | Traes_2BL_84B12F4F8 | TaMEKK18 | 1262 | 47 | 5.86 | 139.6 | Nuclear | scaffold_2BL_8013221:1461-11089 | |

| 19 | TaMAPKKK19 | Traes_2DL_000136878 | TaMEKK19 | 1267 | 44 | 5.69 | 139.8 | Nuclear | 2D:137763450-137774947 | |

| 20 | TaMAPKKK20 | Traes_2AL_66079157A | TaMEKK20 | 1059 | 22 | 5.54 | 116.6 | Nuclear | 2A:238560833-238569155 | |

| 21 | TaMAPKKK21 | Traes_6AS_E690A27CA | TaMEKK21 | 543 | 3 | 6.83 | 61.2 | Cytoplasmic | 6A:131214661-131219615 | |

| 22 | TaMAPKKK22 | Traes_5AL_F9C2BEAF3 | TaMEKK22 | 601 | 5 | 5.4 | 66.2 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 5A:109832378-109839192 | |

| 23 | TaMAPKKK23 | Traes_6DS_185723D1E | TaMEKK23 | 480 | 3 | 6.59 | 54.6 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 6D:52694919-52699797 | |

| 24 | TaMAPKKK24 | Traes_5BL_3EFFD8013 | TaMEKK24 | 547 | 5 | 5.75 | 60.4 | Nuclear | 5B:45438771-45443053 | |

| 25 | TaMAPKKK25 | Traes_5BL_38DB82ACF | TaMEKK25 | 518 | 0 | 6.01 | 56.5 | Cytoplasmic Chloroplast | 5B:75941978-75943867 | |

| 26 | TaMAPKKK26 | Traes_2DS_122AEE879 | TaMEKK26 | 1302 | 4 | 7.79 | 142.3 | PlasmaMembrane | scaffold_2DS_5390089:1-10763 | |

| 27 | TaMAPKKK27 | Traes_2BS_8506C57C5 | TaMEKK27 | 1335 | 5 | 8.01 | 146.1 | PlasmaMembrane | scaffold_2BS_1798276:2-10405 | |

| 28 | TaMAPKKK28 | Traes_2AS_F0521C4F2 | TaMEKK28 | 1332 | 5 | 8.09 | 145.9 | PlasmaMembrane | 2A:17064310-17075483 | |

| 29 | TaMAPKKK29 | Traes_5DL_243735D6C | TaMEKK29 | 617 | 5 | 5.89 | 68.0 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 5D:48513467-48518535 | |

| 30 | TaMAPKKK30 | Traes_5DL_9824E97A8 | ZIK | TaZIK1 | 640 | 17 | 5.71 | 70.6 | Nuclear | scaffold_5DL_4596034:10027-17090 |

| 31 | TaMAPKKK31 | Traes_6DL_F70F83614 | TaZIK2 | 616 | 13 | 4.86 | 68.9 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_6DL_3325277:1-4055 | |

| 32 | TaMAPKKK32 | Traes_2AS_2B84A0A98 | TaZIK3 | 650 | 33 | 5.56 | 72.9 | Nuclear | scaffold_2AS_3354645:196-4869 | |

| 33 | TaMAPKKK33 | Traes_6BL_4A17F7221 | TaZIK4 | 617 | 13 | 4.89 | 69.0 | Nuclear | scaffold_6BL_4289517:41-4156 | |

| 34 | TaMAPKKK34 | Traes_2DS_AA3E486F3 | TaZIK5 | 321 | 16 | 6.62 | 36.2 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 2D:43089164-43091159 | |

| 35 | TaMAPKKK35 | Traes_2AS_E27D25DA3 | TaZIK6 | 213 | 13 | 6.1 | 24.1 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 2A:69759079-69760992 | |

| 36 | TaMAPKKK36 | Traes_2BS_18264AA5C | TaZIK7 | 703 | 32 | 5.61 | 78.6 | Nuclear | 2B:135976808-135980180 | |

| 37 | TaMAPKKK37 | Traes_2BS_1E887CFE5 | TaZIK8 | 292 | 13 | 6.1 | 33.0 | Cytoplasmic | 2B:157476501-157478662 | |

| 38 | TaMAPKKK38 | Traes_1DS_34EFDA767 | TaZIK9 | 243 | 3 | 5.91 | 27.9 | Cytoplasmic | 1D:3919344-3922775 | |

| 39 | TaMAPKKK39 | Traes_6AL_48165ABE5 | TaZIK10 | 616 | 13 | 4.82 | 68.9 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 6A:166642548-166647057 | |

| 40 | TaMAPKKK40 | Traes_5BL_4002B5518 | TaZIK11 | 640 | 17 | 5.55 | 70.5 | Nuclear | 5B:140747940-140754957 | |

| 41 | TaMAPKKK41 | Traes_6DS_D8750EB5A | Raf | TaRaf1 | 326 | 3 | 8.65 | 36.6 | Nuclear | scaffold_6DS_1052516:1426-2508 |

| 42 | TaMAPKKK42 | Traes_2BL_4CAF2C184 | TaRaf2 | 149 | 7 | 5.07 | 16.5 | Extracellular | 2B:344488349-344489312 | |

| 43 | TaMAPKKK43 | Traes_6BL_01E6CE316 | TaRaf3 | 882 | 10 | 6 | 99.6 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 6B:192776834-192783783 | |

| 44 | TaMAPKKK44 | Traes_2DS_DFE006BB6 | TaRaf4 | 236 | 19 | 6.08 | 26.9 | PlasmaMembrane | 2D:2355728-2357164 | |

| 45 | TaMAPKKK45 | Traes_3DL_CFCA7AA6B | TaRaf5 | 280 | 10 | 6.1 | 31.7 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_3DL_6928571:2813-4619 | |

| 46 | TaMAPKKK46 | Traes_2DS_0BFF3B23D | TaRaf6 | 342 | 4 | 6.26 | 38.9 | Cytoplasmic | 2D:9025906-9028377 | |

| 47 | TaMAPKKK47 | Traes_7DS_361EC0618 | TaRaf7 | 454 | 0 | 5.3 | 50.8 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 7D:151974-158365 | |

| 48 | TaMAPKKK48 | Traes_7DS_A3EB5BFEB | TaRaf8 | 272 | 19 | 5.82 | 30.8 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | 7D:15224206-15225510 | |

| 49 | TaMAPKKK49 | Traes_7DS_7A0BEA59B | TaRaf9 | 267 | 14 | 6.79 | 30.1 | Cytoplasmic Chloroplast | 7D:15301325-15302622 | |

| 50 | TaMAPKKK50 | Traes_7DS_D56FBFFD4 | TaRaf10 | 180 | 12 | 4.86 | 19.9 | PlasmaMembrane | 7D:19252002-19255310 | |

| 51 | TaMAPKKK51 | Traes_7DS_5A97B2141 | TaRaf11 | 177 | 5 | 5.25 | 20.1 | Cytoplasmic | 7D:44647285-44648284 | |

| 52 | TaMAPKKK52 | Traes_7DS_342F25C32 | TaRaf12 | 380 | 4 | 8.56 | 42.8 | PlasmaMembrane | 7D:87713571-87717063 | |

| 53 | TaMAPKKK53 | Traes_1BL_C9B36DE76 | TaRaf13 | 247 | 15 | 5.83 | 27.8 | Cytoplasmic | 1B:269260712-269261808 | |

| 54 | TaMAPKKK54 | Traes_7DL_F0110933B | TaRaf14 | 714 | 17 | 6.28 | 79.7 | Extracellular Cytoplasmic | 7D:221995565-222000466 | |

| 55 | TaMAPKKK55 | Traes_3DS_0694296CB | TaRaf15 | 199 | 33 | 6.2 | 22.1 | Cytoplasmic | 3D:812187-813154 | |

| 56 | TaMAPKKK56 | Traes_3DS_4E61EE6EA | TaRaf16 | 180 | 16 | 4.94 | 20.0 | PlasmaMembrane | 3D:2782290-2783296 | |

| 57 | TaMAPKKK57 | Traes_3DS_6801BD0D2 | TaRaf17 | 279 | 33 | 5.24 | 31.3 | PlasmaMembrane | 3D:3073536-3075436 | |

| 58 | TaMAPKKK58 | Traes_3DL_B28036C5B | TaRaf18 | 284 | 19 | 7.05 | 31.7 | Cytoplasmic | 3D:56193757-56197452 | |

| 59 | TaMAPKKK59 | Traes_2AS_9219695D6 | TaRaf19 | 340 | 6 | 5.89 | 37.4 | Cytoplasmic Chloroplast | 2A:121409421-121412207 | |

| 60 | TaMAPKKK60 | Traes_2AS_79A94F84A | TaRaf20 | 229 | 1 | 6.44 | 26.1 | PlasmaMembrane | 2A:155554112-155555589 | |

| 61 | TaMAPKKK61 | Traes_7DL_705BA7CDD | TaRaf21 | 218 | 3 | 9.24 | 24.9 | Mitochondrial Nuclear | 7D:60185604-60186553 | |

| 62 | TaMAPKKK62 | Traes_4AL_1C557F688 | TaRaf22 | 255 | 6 | 5.9 | 28.5 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | 4A:171143548-171144835 | |

| 63 | TaMAPKKK63 | Traes_4AL_06A8F8B8F | TaRaf23 | 287 | 13 | 7.19 | 32.5 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | 4A:183127766-183129049 | |

| 64 | TaMAPKKK64 | Traes_4AL_FEFC21AAB | TaRaf24 | 709 | 2 | 5.24 | 79.4 | Cytoplasmic | 4A:211420094-211424697 | |

| 65 | TaMAPKKK65 | Traes_4AL_C217A20A1 | TaRaf25 | 741 | 3 | 5.79 | 82.8 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | 4A:211772709-211779190 | |

| 66 | TaMAPKKK66 | Traes_1DL_FB90601E7 | TaRaf26 | 348 | 5 | 6.76 | 30.5 | Cytoplasmic Mitochondrial Nuclear | 1D:93818790-93820691 | |

| 67 | TaMAPKKK67 | Traes_1DL_F49D0E56A | TaRaf27 | 248 | 15 | 5.54 | 28.0 | Cytoplasmic | 1D:116551471-116552444 | |

| 68 | TaMAPKKK68 | Traes_1DL_A0FB3E1D3 | TaRaf28 | 193 | 14 | 5.14 | 21.7 | Extracellular Cytoplasmic | 1D:129495165-129496613 | |

| 69 | TaMAPKKK69 | Traes_2DL_C5A0BDC60 | TaRaf29 | 271 | 18 | 9.33 | 31.0 | Mitochondrial Nuclear | 2D:144590634-144593681 | |

| 70 | TaMAPKKK70 | Traes_1DL_56B195A26 | TaRaf30 | 289 | 25 | 7.49 | 31.9 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 1D:129622264-129624911 | |

| 71 | TaMAPKKK71 | Traes_6AS_006C344A3 | TaRaf31 | 786 | 6 | 5.89 | 90.0 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 6A:146084-152036 | |

| 72 | TaMAPKKK72 | Traes_3AS_A2CECBF17 | TaRaf32 | 243 | 30 | 6.34 | 26.9 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 3A:1529045-1530295 | |

| 73 | TaMAPKKK73 | Traes_3AS_769E90DDD | TaRaf33 | 268 | 13 | 8.12 | 29.9 | PlasmaMembrane | 3A:4632011-4633193 | |

| 74 | TaMAPKKK74 | Traes_3AS_5AF26B2FC | TaRaf34 | 327 | 10 | 6.72 | 36.8 | PlasmaMembrane | 3A:5100634-5102019 | |

| 75 | TaMAPKKK75 | Traes_3AS_A542EC6F6 | TaRaf35 | 305 | 8 | 7.21 | 34.3 | Mitochondrial | 3A:15435755-15437806 | |

| 76 | TaMAPKKK76 | Traes_3AL_7F6E774BB | TaRaf36 | 253 | 11 | 5.27 | 28.3 | Cytoplasmic | 3A:91931309-91932151 | |

| 77 | TaMAPKKK77 | Traes_3AL_943665768 | TaRaf37 | 279 | 18 | 7.05 | 31.2 | Cytoplasmic | 3A:107041859-107044259 | |

| 78 | TaMAPKKK78 | Traes_3AL_60BB7086F | TaRaf38 | 183 | 33 | 8.44 | 20.6 | PlasmaMembrane Nuclear | 3A:178617601-178618324 | |

| 79 | TaMAPKKK79 | Traes_3AL_F384515F5 | TaRaf39 | 188 | 24 | 4.81 | 21.0 | Extracellular Cytoplasmic | 3A:180162239-180164198 | |

| 80 | TaMAPKKK80 | Traes_2AS_0C8932B8E | TaRaf40 | 339 | 7 | 5.54 | 38.8 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 2A:180067672-180069167 | |

| 81 | TaMAPKKK81 | Traes_5AL_3FE725FD4 | TaRaf41 | 775 | 2 | 6.28 | 88.0 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 5A:82903861-82912218 | |

| 82 | TaMAPKKK82 | Traes_5AL_A236B0387 | TaRaf42 | 259 | 11 | 5.49 | 29.2 | Cytoplasmic | 5A:96483013-96484223 | |

| 83 | TaMAPKKK83 | Traes_5AL_CDD4A02E7 | TaRaf43 | 299 | 5 | 6.36 | 33.8 | PlasmaMembrane | 5A:97062318-97064376 | |

| 84 | TaMAPKKK84 | Traes_5AL_13784C39B | TaRaf44 | 233 | 6 | 5.46 | 26.3 | PlasmaMembrane | 5A:97195379-97196530 | |

| 85 | TaMAPKKK85 | Traes_5AL_68C659562 | TaRaf45 | 272 | 8 | 5.2 | 30.6 | PlasmaMembrane | 5A:99451668-99452790 | |

| 86 | TaMAPKKK86 | Traes_5AL_7B1C0342F | TaRaf46 | 339 | 40 | 8.16 | 38.0 | Extracellular PlasmaMembrane | 5A:105814700-105817645 | |

| 87 | TaMAPKKK87 | Traes_1AS_BEE845715 | TaRaf47 | 388 | 18 | 6.32 | 43.0 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 1A:100519-103703 | |

| 88 | TaMAPKKK88 | Traes_1AL_C21696173 | TaRaf48 | 332 | 27 | 6.25 | 36.8 | Nuclear | 1A:243280434-243282190 | |

| 89 | TaMAPKKK89 | Traes_7AS_51069274F | TaRaf49 | 264 | 17 | 6.13 | 29.8 | Cytoplasmic | 7A:12995054-12996342 | |

| 90 | TaMAPKKK90 | Traes_7AS_81545C211 | TaRaf50 | 214 | 3 | 8.93 | 24.0 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 7A:27180845-27181770 | |

| 91 | TaMAPKKK91 | Traes_4DS_7D8A5F90B | TaRaf51 | 755 | 4 | 6.45 | 85.9 | Cytoplasmic | 4D:38444291-38457344 | |

| 92 | TaMAPKKK92 | Traes_5DL_3191490FE | TaRaf52 | 160 | 50 | 7.02 | 18.0 | Cytoplasmic | 5D:119596889-119599696 | |

| 93 | TaMAPKKK93 | Traes_5BS_0B466F42F | TaRaf53 | 278 | 0 | 7.59 | 31.8 | Nuclear | 5B:4053009-4053978 | |

| 94 | TaMAPKKK94 | Traes_5BS_43731B6AC | TaRaf54 | 285 | 8 | 6.41 | 30.4 | Cytoplasmic Chloroplast | 5B:4123947-4125118 | |

| 95 | TaMAPKKK95 | Traes_5BL_E44E042FD | TaRaf55 | 344 | 6 | 9.3 | 37.6 | Nuclear | 5B:106916097-106920463 | |

| 96 | TaMAPKKK96 | Traes_5BL_2DA8896EE | TaRaf56 | 784 | 2 | 8.4 | 88.3 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 5B:178405794-178411614 | |

| 97 | TaMAPKKK97 | Traes_5BL_11A7A1F5C | TaRaf57 | 205 | 9 | 9.3 | 23.2 | Cytoplasmic | 5B:206004103-206004989 | |

| 98 | TaMAPKKK98 | Traes_5DL_294C4EDB3 | TaRaf58 | 387 | 49 | 7.58 | 42.2 | Nuclear | 5D:148108984-148113098 | |

| 99 | TaMAPKKK99 | Traes_3AS_2A0765E10 | TaRaf59 | 279 | 29 | 8.13 | 31.2 | PlasmaMembrane | 3A:671046-672777 | |

| 100 | TaMAPKKK100 | Traes_3AL_82306B917 | TaRaf60 | 316 | 9 | 6.82 | 35.9 | Cytoplasmic | 3A:154206856-154208804 | |

| 101 | TaMAPKKK101 | Traes_5DS_53F8C78FA | TaRaf61 | 199 | 8 | 6.01 | 21.1 | Cytoplasmic | 5D:10503237-10504290 | |

| 102 | TaMAPKKK102 | Traes_7BL_46880A4FE | TaRaf62 | 280 | 119 | 8.7 | 31.5 | Mitochondrial | scaffold_7BL_6485684:8-1478 | |

| 103 | TaMAPKKK103 | Traes_7AL_9AD23808D | TaRaf63 | 314 | 2 | 6.9 | 35.4 | Cytoplasmic | 7A:84246015-84251550 | |

| 104 | TaMAPKKK104 | Traes_1DL_0162A6BAC | TaRaf64 | 241 | 7 | 5.98 | 26.8 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_1DL_2275852:3-2035 | |

| 105 | TaMAPKKK105 | Traes_3AS_A0EA6D12C | TaRaf65 | 210 | 7 | 6.08 | 24.0 | Cytoplasmic Mitochondrial Nuclear | scaffold_3AS_1117810:1-1084 | |

| 106 | TaMAPKKK106 | Traes_4AL_48E7FB1C6 | TaRaf66 | 197 | 11 | 6.15 | 22.5 | PlasmaMembrane | scaffold_4AL_7145827:1-952 | |

| 107 | TaMAPKKK107 | Traes_4AL_83D9333FE | TaRaf67 | 154 | 9 | 6.82 | 17.4 | PlasmaMembrane | scaffold_4AL_7109061:3-710 | |

| 108 | TaMAPKKK108 | Traes_5DL_62B6846F6 | TaRaf68 | 191 | 7 | 6.3 | 21.7 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | scaffold_5DL_4605280:630-1568 | |

| 109 | TaMAPKKK109 | Traes_2DS_42A9CC22D | TaRaf69 | 252 | 3 | 5.24 | 27.9 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_2DS_838920:50-1605 | |

| 110 | TaMAPKKK110 | Traes_4BL_3626CDB73 | TaRaf70 | 265 | 1 | 5.61 | 28.8 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_4BL_7036128:2-919 | |

| 111 | TaMAPKKK111 | Traes_3AL_5DC02A5FC | TaRaf71 | 302 | 7 | 6.14 | 33.3 | Cytoplasmic Chloroplast | scaffold_3AL_1833470:519-2133 | |

| 112 | TaMAPKKK112 | Traes_5DL_0A74AE348 | TaRaf72 | 297 | 5 | 5.76 | 33.5 | PlasmaMembrane | 5D:124050225-124051615 | |

| 113 | TaMAPKKK113 | Traes_3AS_C492FCE9A | TaRaf73 | 242 | 3 | 6.52 | 27.1 | Nuclear | scaffold_3AS_2578257:98-1277 | |

| 114 | TaMAPKKK114 | Traes_4AL_32D968595 | TaRaf74 | 270 | 17 | 6.1 | 30.5 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_4AL_7089761:892-2199 | |

| 115 | TaMAPKKK115 | Traes_3AL_0187ECBAC | TaRaf75 | 159 | 7 | 5.39 | 17.9 | Cytoplasmic Chloroplast | scaffold_3AL_4340950:1-1036 | |

| 116 | TaMAPKKK116 | Traes_1BL_1E2841006 | TaRaf76 | 267 | 19 | 6.24 | 30.2 | Extracellular Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_1BL_3793082:882-2495 | |

| 117 | TaMAPKKK117 | Traes_3DS_0B1914F50 | TaRaf77 | 305 | 9 | 6.9 | 34.3 | Cytoplasmic Mitochondrial | scaffold_3DS_2550735:71-2194 | |

| 118 | TaMAPKKK118 | Traes_5DL_5DAC7A4CF | TaRaf78 | 497 | 3 | 5.88 | 56.4 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_5DL_4513923:4360-10186 | |

| 119 | TaMAPKKK119 | Traes_2AL_0E43EBBB6 | TaRaf79 | 180 | 13 | 7.06 | 20.3 | Mitochondrial | scaffold_2AL_6381182:1-1586 | |

| 120 | TaMAPKKK120 | Traes_4AL_9601B9873 | TaRaf80 | 314 | 4 | 6.96 | 34.7 | Nuclear | scaffold_4AL_7096965:1880-5803 | |

| 121 | TaMAPKKK121 | Traes_2DS_964FA3D25 | TaRaf81 | 245 | 13 | 4.64 | 27.1 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_2DS_5355140:3031-4467 | |

| 122 | TaMAPKKK122 | Traes_2AS_DCD2F10331 | TaRaf82 | 311 | 9 | 6.23 | 34.8 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_2AS_2039357:2956-4095 | |

| 123 | TaMAPKKK123 | Traes_5DL_A367964F5 | TaRaf83 | 225 | 10 | 8.79 | 25.2 | Cytoplasmic | 5D:124089352-124090277 | |

| 124 | TaMAPKKK124 | Traes_2AS_AC9886ABC | TaRaf84 | 225 | 12 | 8.88 | 25.3 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_2AS_5255912:5418-6352 | |

| 125 | TaMAPKKK125 | Traes_7DS_81C827CE6 | TaRaf85 | 363 | 4 | 6.27 | 40.5 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | scaffold_7DS_3862762:1862-7469 | |

| 126 | TaMAPKKK126 | Traes_6BS_511AB47D71 | TaRaf86 | 339 | 19 | 5.59 | 38.1 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | scaffold_6BS_3043664:2-1698 | |

| 127 | TaMAPKKK127 | Traes_6DL_7662129AC | TaRaf87 | 928 | 55 | 5.77 | 104.3 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_6DL_3324907:1786-5987 | |

| 128 | TaMAPKKK128 | Traes_1BL_CDC566E72 | TaRaf88 | 289 | 25 | 7.97 | 32.0 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_1BL_3828880:5213-7383 | |

| 129 | TaMAPKKK129 | Traes_6BL_658AE8589 | TaRaf89 | 280 | 1 | 5.7 | 31.6 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_6BL_4262535:303-3102 | |

| 130 | TaMAPKKK130 | Traes_7AS_0BE0D89AC | TaRaf90 | 251 | 14 | 5.79 | 28.6 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | scaffold_7AS_4255305:1753-2961 | |

| 131 | TaMAPKKK131 | Traes_6BS_EAABDE59A | TaRaf91 | 250 | 47 | 9.14 | 28.4 | Extracellular Mitochondrial | scaffold_6BS_3021108:276-3989 | |

| 132 | TaMAPKKK132 | Traes_5BL_17A56822E | TaRaf92 | 221 | 6 | 7.69 | 24.8 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | scaffold_5BL_10894314:6618-8227 | |

| 133 | TaMAPKKK133 | Traes_1BS_EA26D2661 | TaRaf93 | 388 | 18 | 6.32 | 42.5 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_1BS_3482116:8155-10572 | |

| 134 | TaMAPKKK134 | Traes_5DL_383D5A71F | TaRaf94 | 189 | 11 | 5.94 | 21.0 | PlasmaMembrane Nuclear | 5D:157768052-157768754 | |

| 135 | TaMAPKKK135 | Traes_2DL_77990F25A | TaRaf95 | 319 | 1 | 7.11 | 36.4 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_2DL_9829349:7066-8506 | |

| 136 | TaMAPKKK136 | Traes_2BS_C0AED9734 | TaRaf96 | 219 | 2 | 4.72 | 24.5 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_2BS_5191771:1720-2933 | |

| 137 | TaMAPKKK137 | Traes_3DL_73ACAB95C | TaRaf97 | 309 | 9 | 6.14 | 34.8 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_3DL_6924167:1792-4345 | |

| 138 | TaMAPKKK138 | Traes_7DS_03068057C | TaRaf98 | 259 | 0 | 7.07 | 29.6 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_7DS_3924816:112-1661 | |

| 139 | TaMAPKKK139 | Traes_3AL_AB54706CA | TaRaf99 | 381 | 26 | 5.69 | 43.1 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_3AL_4360739:391-3058 | |

| 140 | TaMAPKKK140 | Traes_5BS_F1687AA56 | TaRaf100 | 231 | 30 | 9.33 | 27.1 | Mitochondrial | scaffold_5BS_2278981:2727-5793 | |

| 141 | TaMAPKKK141 | Traes_7DS_A46AFAE10 | TaRaf101 | 918 | 5 | 6.62 | 102.6 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic | scaffold_7DS_3809424:2024-7790 | |

| 142 | TaMAPKKK142 | Traes_2AS_CC27D1C41 | TaRaf102 | 248 | 8 | 7.64 | 27.8 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_2AS_5226094:20239-21469 | |

| 143 | TaMAPKKK143 | Traes_2AS_AC9886ABC1 | TaRaf103 | 225 | 12 | 8.88 | 25.3 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | scaffold_2AS_5255913:5418-6352 | |

| 144 | TaMAPKKK144 | Traes_3DL_3D1CAD68F | TaRaf104 | 188 | 15 | 4.84 | 20.9 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_3DL_6944830:139-1513 | |

| 145 | TaMAPKKK145 | Traes_2BS_5C64FC44A | TaRaf105 | 265 | 11 | 6.33 | 29.8 | Cytoplasmic | 2B:125675753-125677190 | |

| 146 | TaMAPKKK146 | Traes_4BS_C5AB35B0C | TaRaf106 | 203 | 10 | 5.84 | 22.6 | Mitochondrial Chloroplast | scaffold_4BS_948180:48-952 | |

| 147 | TaMAPKKK147 | Traes_2AS_E5AB3458C | TaRaf107 | 347 | 3 | 6.57 | 39.6 | Nuclear | scaffold_2AS_5232094:4234-6292 | |

| 148 | TaMAPKKK148 | Traes_1BS_41E5F1990 | TaRaf108 | 269 | 6 | 6.09 | 30.9 | Cytoplasmic | scaffold_1BS_3451546:6832-8016 | |

| 149 | TaMAPKKK149 | Traes_3B_582DCEA06 | TaRaf109 | 352 | 8 | 7.74 | 39.2 | Cytoplasmic Mitochondrial | scaffold_3B_10637137:56-2229 | |

| 150 | TaMAPKKK150 | TRAES3BF061500080CFD_t1 | TaRaf110 | 340 | 30 | 5.29 | 37.6 | Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 3B:1864715-1866712 | |

| 151 | TaMAPKKK151 | TRAES3BF104900080CFD_t1 | TaRaf111 | 1005 | 9 | 6.67 | 111.9 | Nuclear | 3B:97278846-97291325 | |

| 152 | TaMAPKKK152 | TRAES3BF026200090CFD_t1 | TaRaf112 | 396 | 9 | 6.24 | 43.7 | Cytoplasmic | 3B:421410785-421414323 | |

| 153 | TaMAPKKK153 | TRAES3BF086600060CFD_t1 | TaRaf113 | 302 | 8 | 6.25 | 33.4 | Cytoplasmic Mitochondrial | 3B:552717475-552718658 | |

| 154 | TaMAPKKK154 | TRAES3BF078400040CFD_t1 | TaRaf114 | 775 | 3 | 5.67 | 87.6 | PlasmaMembrane Cytoplasmic Nuclear | 3B:696462241-696470991 | |

| 155 | TaMAPKKK155 | Traes_6BS_5BFDC774A | TaRaf115 | 318 | 2 | 5.2 | 36.1 | PlasmaMembrane | 6B:84413110-84414856 |

To support the actual existence of these wheat MAPKKKs, we further performed a BLASTN search against the wheat expressed sequence tag (EST) and unigene database using the MAPKKKs as query. Results showed that most of the TaMAPKKKs’ existences were supported by EST hits except 6 MAPKKKs (TaMEKK4, TaMEKK13, TaMEKK25, TaRaf7, TaRaf53 and TaRaf98). We speculated these 6 not-support TaMAPKKKs might not express under any the used conditions or express with very low level that cannot be detected experimentally. Among the supported TaMAPKKK genes, TaRaf62 has the largest hits of ESTs, with the number of 119, followed by TaMEKK5 and TaRaf87 with the number of 95 and 55 ESTs, respectively.

Chromosome localization analysis found that the 155 TaMAPKKK genes were unevenly distributed on all the 21 wheat chromosomes, of which chromosome 3A contained the most MAPKKK genes with the number of 15, followed by 2A with the number of 14, then 5B, 5D as well as 7D all with the number of 11, while the chromosome 7B had the least MAPKKK gene, with the number of only 1. Furthermore, the length of putative TaMAPKKK proteins ranged from 149 to 1335 amino acids, with the putative molecular weight (Mw) ranging from 16.5 to 146.1 kDa and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) ranging from 4.55 to 9.33, respectively. The subcellular localization analysis found that a total of 51 TaMAPKKKs localized in nuclear, 42 localized in cytoplasmic and 32 localized in plasma membrane, while the remaining were predicted to be located in chloroplast, mitochondrial and extra-cellular (Table 2).

Phylogenetic and conserved domains analysis of TaMAPKKKs

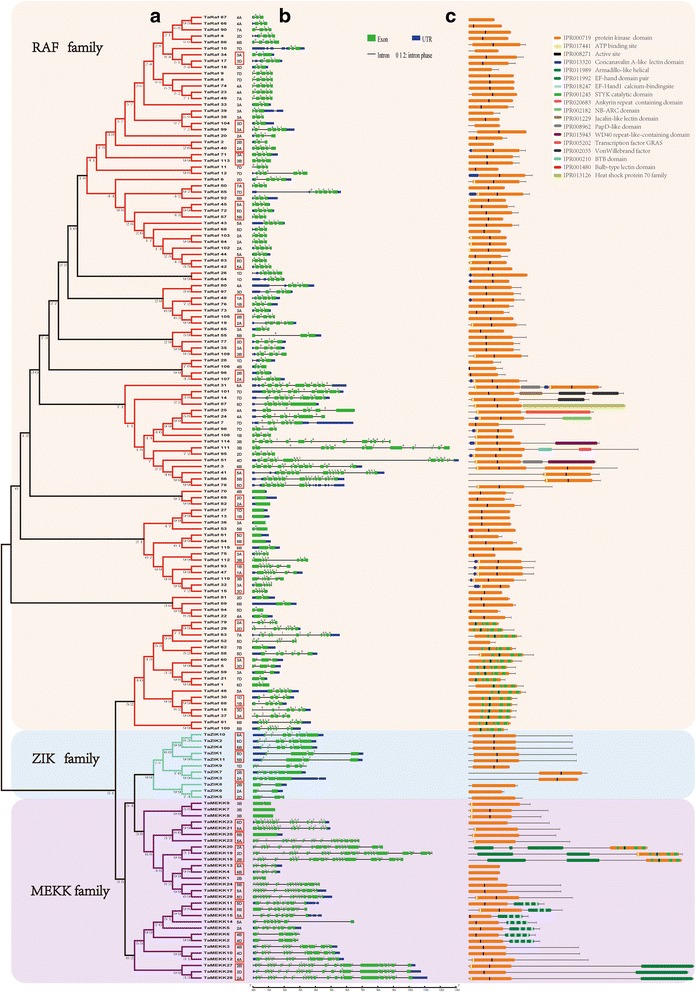

To further evaluate the phylogenetic relationships of the wheat MAPKKK cascade genes, the full-length protein sequences of the 155 TaMAPKKKs were aligned using ClustalW software and then the phylogenetic tree were constructed using the neighbor joining (NJ) method integrated into MEGA6.0 (Fig. 2a). On the basis of phylogenetic analysis, MAPKKKs in wheat were clustered into three major groups, of which MEKK, Raf and ZIK subfamily members clustered together into one category, respectively. It is found that the bootstrap value of the phylogenetic tree is low, which may due to the low similarity of the full-length protein sequences, suggesting that there are high sequence differentiation in these MAPKKK genes although the conserved motifs were included, which was consistent with the MAPKKKs in maize [12], rice [13] and Brachypodium [15, 32]. The conserved domains and phylogenetic relationship suggested that MAPKKK genes showing the closer phylogenetic relationship may have the similar biological function. To date, there is no report regarding MAPKKK genes in T. aestivum, so searching for MAPKKK family genes and understanding their phylogenetic relationship in T. aestivum is necessary and helpful for their further functional study.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships (a), gene structures (b) and protein structures (c) of MAPKKK genes in wheat

Furthermore, the protein domains of these wheat MAPKKK genes were identified by searching against InterProScan databases (Fig. 2c). Results found that each cluster of the MAPKKKs classified by phylogenetic analysis shared the similar protein structure and domain composition, demonstrating that the protein architecture is remarkably conserved within a specific subfamily of MAPKKKs. Protein kinases have been demonstrated to play the crucial role in mediating process of protein phosphorylation, which widely occurred in most cellular activities [32]. In this study, we found all the TaMAPKKK proteins contained a kinase domain (IPR000719), and most of them had the serine/threonine protein kinase active site (IPR008271) in the central part of the catalytic domain. These features were also found in the MAPKKK proteins of rice and cucumber [13, 33], suggesting the conserved function of MAPKKK genes in plants. Moreover, the ATP-binding site, which is located on the catalytic domain, is the most conserved sequences in the kinase family [33]. We found that most of TaMAPKKKs also contained an ATP-binding site (IPR017441), suggesting that these wheat MAPK cascade kinases use ATP as the ligand in signal transduction pathway. In addition, the TaMAPKKKs also had some other conserved domains, such as concanavalin A-like lectin/glucanase domain (IPR013320), armadillo-like helical (IPR011989), and EF-hand domain (IPR011992). Interestingly, these TaMAPKKKs containing the same protein domains were generally clustered into the same clade in phylogenetic analysis, and showed similar expression patterns in response to multiple stresses, which was consistent with the result of BdMAPKKK genes as reported previously [32]. For example, most TaMAPKKK genes containing concanavalin A-like lectin/glucanase domain were up-regulated by drought stress, while those genes containing armadillo-like helical domain showed to be down-regulated under salt stress. These results indicated that the various protein domains could regulate the TaMAPKKK gene to exhibit specific biological functions. The conserved domains identification and analysis may facilitate the identification of functional units in these kinase genes and accelerate to understand their crucial roles in plant growth and development as well as stresses response [34, 35].

Analyses of gene structures and promoter regions of TaMAPKKKs

Gene structure analysis can provide important information about the gene function, organization and evolution [36]. Thus, the exon/intron structures of TaMAPKKK genes were further analyzed using the available wheat genome annotation information and then were displayed by the Gene Structure Display Server (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) (Fig. 2b). We found the exon/intron structures in the TaMAPKKK genes were relatively conserved within the subfamily but some divergent between different subfamily. The Raf and MEKK subfamily have more sophisticated structure than ZIK subfamily due to the various number of intron. In detail, all the ZIK genes had introns, with the number ranging from 1 to 7. In the MEKK subfamily, 3 gene had no intron, and others had 1 to 22 introns, which was the most highly variable in the number of introns in TaMAPKKKs. In the Raf subfamily, 7 out 115 genes had no intron, and other Raf genes had the intron number ranging from 1 to 14. Interestingly, most gene pairs clustered together by phylogenetic analysis shared the similar exon/intron structure and intron phases in these TaMAPKKK genes, suggesting the evolutionary event may impact not only on the gene function but also on gene structure. It has been revealed that intron gain or loss is the results of selection pressures during evolution in plants, and the genes tend to evolve into diverse exon-intron structures and perform differential functions [37, 38]. Accordingly, the wheat MAPKKK genes were found to have the similar exon-intron structure within same subfamily, while the numbers of introns were varied, even within subfamily, which indicated that gene differentiation have occurred in the wheat MAPKKK to accomplish different biological functions under the selection pressure during the wheat genome formation and evolution.

Promoter is the region of the transcription factors (TF) binding site to initiate transcription, which plays a key role in regulating gene spatial and temporal expressions [39]. To further detect the possible biological function and transcription regulation of these TaMAPKKKs, the 2 kb-upstream region of the transcriptional start site of all these genes were extracted and then used to screen for cis-regulatory elements. Results showed that a large number of stress-related and hormone-related cis-elements were found in promoter regions of the wheat MAPKKK genes (Additional file 3), which were similar with the result in Brachypodium, tomato and cucumber [32, 33, 36]. In addition, the abiotic stress-related (a total of 9 drought-stress, 1 salt-stress, 1 heat-stress, 1 cold-stress, 2 wound-stress and 2 disease resistance-related) and hormones signaling transduction-related (6 gibberellins, 4 abscisic acid and 3 ethylene-related) cis-regulatory elements were also found, suggesting that the wheat MAPKKKs may involve in regulating varieties of stress responses and hormone signaling transduction processes.

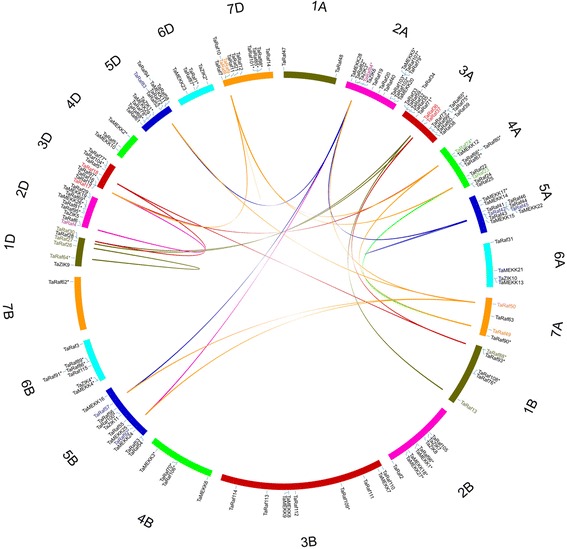

Genomic distribution and gene duplication of TaMAPKKK gene family

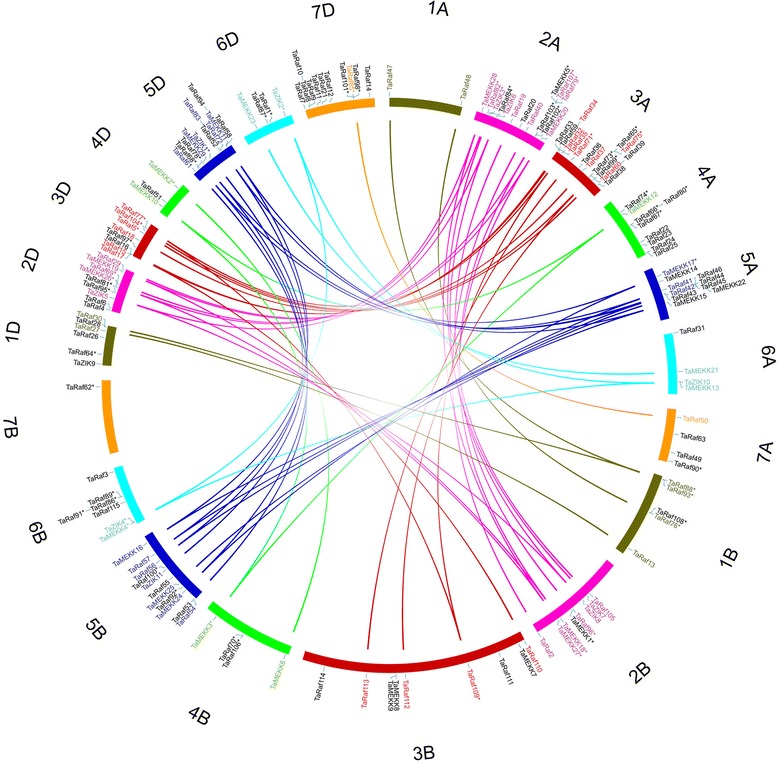

Based on the available wheat genome annotation information, the chromosomal location of the TaMAPKKK genes were further investigated (Fig. 3). A total of 58, 45, and 52 TaMAPKKK genes are distributed in the A, B and D sub-genome, respectively (A > D > B). Initial gene loss may occurred in B genomes following tetraploidy to decrease functional redundancy and define the core wheat genes, with subsequent loss from all three genomes following the formation of the hexaploid around 9000 years ago. The distribution of MAPKKK genes was not random in wheat chromosomes. There were 13, 31, 32, 16, 32, 15 and 16 genes in the group 1 to 7 chromosomes, which show two obvious gradients between group 2, 3, 5 and other four groups. And chromosome 3A had the highest number of MAPKKK genes with the value of 15 genes, whereas chromosome 7B had only one MAPKKK gene. These results indicates that duplication events of MAPKKK gene have likely occurred in wheat 2, 3 and 5 group chromosomes during wheat formation and the evolution of gene families within the different sub-genome is independent, which may associate with gene functions.

Fig. 3.

Chromosomal localization and the homologous TaMAPKKK genes in wheat A, B and D sub-genomes. The genes followed by * represent that the gene only anchor to scaffold. Seven homologous groups of wheat chromosomes are displayed in different colors. Duplicated genes of each homo-group are displayed in corresponding color and linked using lines with corresponding color

Gene duplication is frequently observed in plant genomes, arising from polyploidization or through tandem and segmental duplication associated with replication [40]. In our study, a total of 11 homologous gene groups with a copy on each of A, B and D homologous chromosome were found in wheat MAPKKK gene family, and 24 gene pairs with a copy on only 2 of the 3 homologous chromosomes were also identified (Fig. 3 and Additional file 4), while the remaining 74 genes were not found homologs in wheat genome. Previous studies have demonstrated that the fractionation from ploidy caused the loss of some homologous sequences because of some combination of deletion [41]. Our results indicated gene loss may also occur in wheat MAPKKK gene family, resulting in the loss of some homologous copies. The specific retention and dispersion of MAPKKKs in homologous chromosomes provide the invaluable information to better understand the wheat chromosome interaction and polyploidization. Furthermore, these homologous genes are clustered in group 2, 3 and 5 chromosomes, which was consistent with the above chromosome localization analysis, suggesting that group 2, 3 and 5 chromosomes suffered less sequence loss and interaction impact compared to other homologous chromosome groups.

Additionally, 25 pairs of duplication genes from different sub-genomes were also identified (Fig. 4 and Additional file 4), including 3 duplication events within the same chromosome and 22 segmental duplication events between different chromosomes, suggesting that the duplication events could play vital roles in the expansion of the MAPK cascade kinase genes in wheat genome. Interestingly, most duplication events occurred between A and D genomes, except the pair of Raf92 and Raf57 occurred on 5B as well as that of Raf13 and Raf88 from 1B. We postulated that the gene family size of the A and B sub-genome have arrived to balance after first hybridization with the long evolutionary process, but the D sub-genome, which was added to form hexaploid wheat recently, appeared to have more interaction with other two sub-genomes. More interestingly, all the 25 pairs of duplication genes belonging to Raf subfamily, which indicates that gene duplication is a main processes responsible for expanding family size and protein functional diversity [42].

Fig. 4.

Duplicated MAPKKK genes pairs identified in wheat. Seven homologous groups of wheat chromosomes are displayed in different colors. Duplicated gene pairs are displayed in corresponding color and linked using lines with the corresponding color

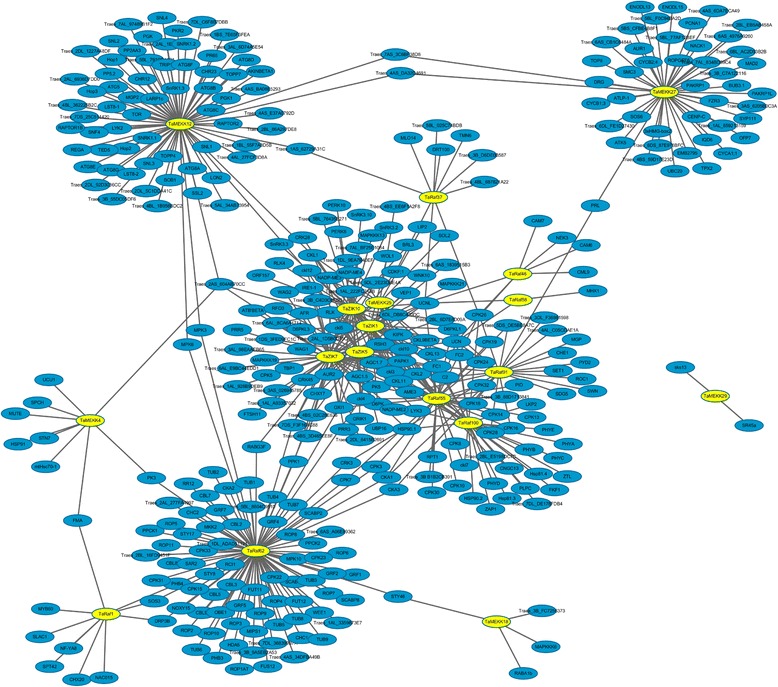

Regulatory network between TaMAPKKK genes with other wheat genes

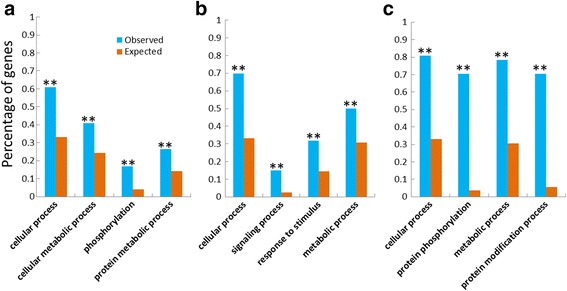

MAPKKKs, as the first step of MAPK cascade, function as the pivotal component linking upstream signaling steps to the core MAPK cascade and then promote the corresponding cellular responses, which are activated by a diversity of external stimuli and interact with other genes to form the signaling regulatory network in plants [2, 31]. To understand the interactions between TaMAPKKKs and other wheat genes, the regulatory network of them (Fig. 5) was predicted using the orthology-based method [43]. Results showed 18 MAPKKKs (6 TaMEKKs, 8 TaRafs and 4 TaZIKs) were found to have homology with Arabidopsis genes, and corresponding 509 gene pairs of network interactions were detected with the average of 28.3 gene/TaMAPKKK, suggesting the MAPKKKs were widely involved in the regulatory network and metabolic processes in wheat (Additional files 5 and 6). Among them, 149 genes were interacted by TaZIKs, and 212 genes were interacted by TaRafs, as well as 148 genes interacted by TaMEKKs, respectively. TaMEKK27 showed orthologous to Arabidopsis Fused (FU) gene, with an active kinase domain and the C-terminal ARM/HEAT repeat domain. Previously study has revealed that Arabidopsis Fused kinase termed TIO is essential for cytokinesis in both sporophytic and gametophytic cell types [44]. In this study, TaMEKK27 was found to interact with 38 wheat genes, including SOS6, NACK1 and FZR3, suggesting it was also mainly involved in cell proliferation and cytokinesis. TaRaf1 is found to interact with 10 wheat genes, which is homology with Arabidopsis HT1 gene reported to encode an important protein kinase for regulation of stomatal movements and corresponding to CO2, ABA and light [45]. The predicted upstream target genes of TaRaf1 included SLAC1, FMA and CHX20 as well as MYB and NAC transcription factor, which indicated TaRaf1 might play a vital role in ion homeostasis and stress response in wheat. Furthermore, Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment of those genes was performed to understand their potential functions. GO descriptions of those interacted genes were involved in diverse biological process, molecular function and stress response. TaMEKK interacted genes were significantly enriched for cellular process and metabolic process, and TaRaf interacted genes were significantly enriched for cellular process and pathways for stress response, while TaZIK interacted genes were functionally enriched in cellular process and protein modification process pathway (Fig. 6a–c), which indicated that TaMAPKKK genes played the vital role in cellular response to external stimuli, especially TaRaf subfamily genes might be the main adaptors to transduce the stress-related signal.

Fig. 5.

The interaction network of TaMAPKKK genes in Wheat according to the orthologs in Arabidopsis

Fig. 6.

Functional categories of genes in MEKK (a), Raf (b), and ZIK (c) subfamily. FDR-adjusted P values, **P < 0.01, respectively. Observed, numbers of genes observed in this study; Expected, numbers of genes in this same category in the GO enrichment analysis program

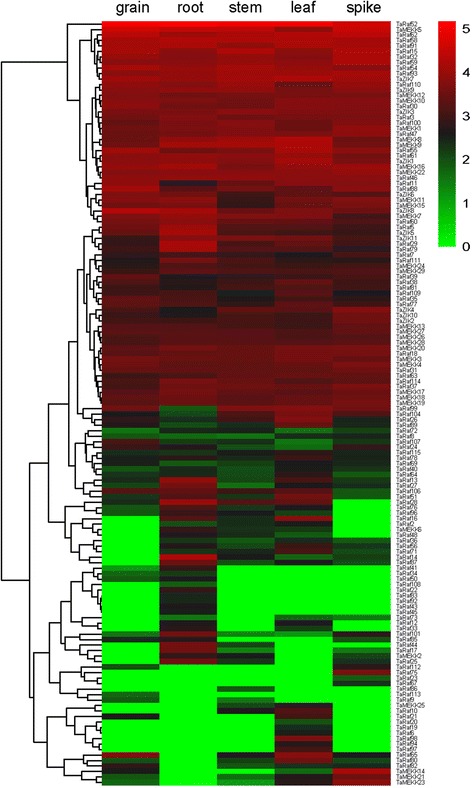

Tissue-specific expression patterns of TaMAPKKK genes

Different members of gene families exhibit great disparities in abundance among different tissues to accommodate different physiological processes [46, 47]. To gain insight into the temporal and spatial expression patterns and putative functions of MAPKKK genes in wheat growth and development, the tissue specificity of the 155 TaMAPKKK genes was investigated using available RNA-seq data for five different tissues [48]. Based on the log10-transformed (FPKM + 1) values, we found that the expression levels of the TaMAPKKKs varied significantly in different tissues (Fig. 7). Most MAPKKK genes were found to be expressed in at least one detected organ. All the members in ZIK subfamily were expressed in all of the 5 organs, while a total of 16 Raf genes had too weak expression abundances to be detected in any tissues, which indicated that these genes have undergone functional differentiation and redundancy. Most of MAPKKK genes were much more highly expressed in the root and leaf compared to grain, stem and spike. Furthermore, the tissue-specific expressed MAPKKK genes were identified. A total of 1, 6, 1, 6 and 3 genes were found to be specifically expressed in grain, root, stem, leaf and spike, respectively. Among them, TaRaf112 was predominantly expressed in grain and spike, TaMEKK25 showed preferential expression in stem and leave, and TaRaf12, TaRaf33 as well as TaRaf73 showed preferential expression in root and leave. As shown in Fig. 7 and Additional file 7, most homologous and duplication genes showed similar expression pattern during development. However, it also should be noted that many clustering of expression profiles does not reflect gene similarities, including the copies of one MAPKKK gene from sub-genomes and duplication genes from different sub-genomes. Some of them even show converse expression patterns. For instance, TaRaf71 which located in 3A showed preferential expression patterns in the root, stem, leaf and spike, whereas its homology gene TaRaf113 from 3B was only expressed in the grain. TaMAPKKK23 in 5A was expressed in all tested organs with relatively higher abundance, while its homology TaMAPKKK25 from 5B only slightly expressed in stem and leaf. The divergences in expression profiles between homologous genes revealed that some of them may lose function or acquire new function after polyploidy and duplication in the wheat evolutionary process.

Fig. 7.

Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of all TaMAPKKK genes in five different organs or tissues (grain, root, stem, leaf and spike). Log10-transformed (FPKM + 1) expression values were used to create the heat map. The red or green colors represent the higher or lower relative abundance of each transcript in each sample

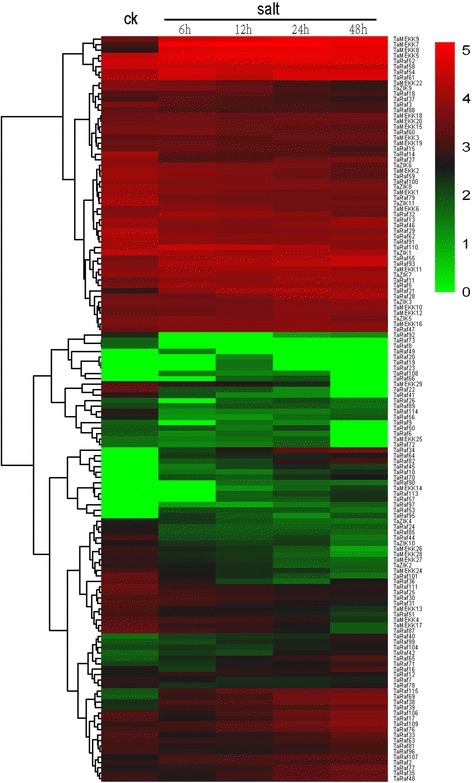

Expression patterns of TaMAPKKK genes under abiotic stresses

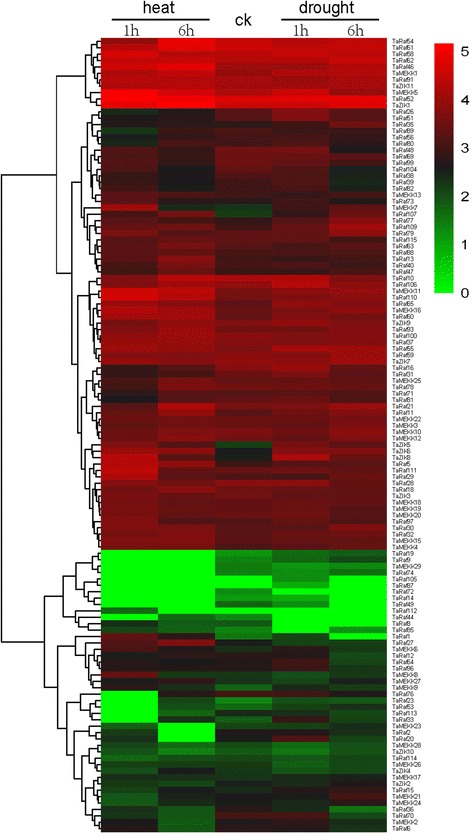

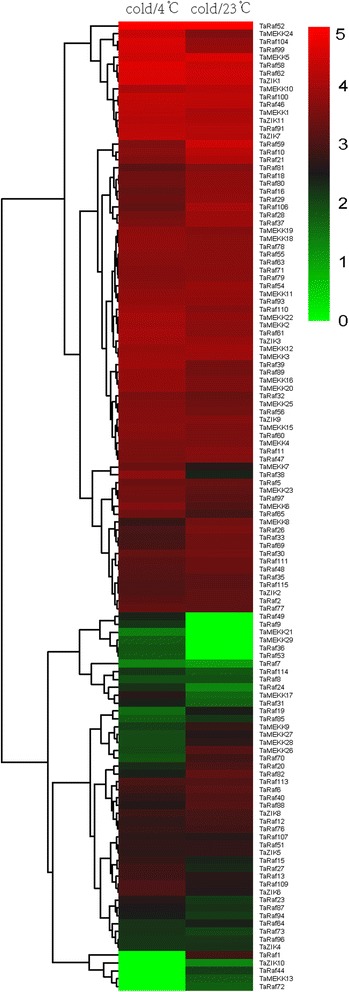

Extensive studies have revealed that the MAPKKK genes played a crucial role in response to abiotic stresses in plant [10, 49, 50]. In the present study, expression patterns of all TaMAPKKK genes in response to four abiotic (salt, heat, drought, cold) stresses were investigated using RNA-seq data to study the roles of TaMAPKKK genes in the response to abiotic stresses. Overall, all the 155 wheat MAPKKK genes showed differential expression patterns under these conditions and most of them were up-regulated in response to more than one stress (Figs. 8, 9 and 10). Among them, TaMEKK14, TaRaf10, TaRaf34 and TaRaf53 showed specific-expression under salt stress, while TaRaf87 and TaRaf105 specifically expressed under drought stress. Meanwhile, TaRaf36 and TaRaf49 were specifically expressed under cold stress while TaRaf112 were specifically expressed under heat stress. In addition, some down-regulated TaMAPKKKs were also observed. TaMEKK29, TaRaf22, TaRaf41, and TaRaf73 was down-regulated under salt stress (Fig. 8), TaMEKK29 showing down-regulated under heat stress, while TaRaf44, TaRaf72 and TaRaf80 showing down-regulated under heat and drought stress (Fig. 9), as well as TaMEKK13, TaRaf1 and TaZIK10 were down-regulated under cold stress (Fig. 10), respectively. These stress-induced MAPKKK genes provided the valuable information to further reveal the roles of TaMAPKKKs playing in regulating wheat diverse stress processes. Finally, the most of the homologous and duplication gene pairs such as TaRaf110/TaRaf32/TaRaf15, and TaMEKK18/ TaMEKK19/ TaMEKK20 showed the similar expression pattern under these stress treatments, suggesting that these had similar physiological functions. On the other hand, several gene pairs such as TaRaf83/TaRaf42 and TaRaf17/TaRaf74, exhibited different expression patterns under the same stress treatments, suggesting functional differentiation has been occurred in these genes and they involved in regulating different stress signaling pathways.

Fig. 8.

Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of all 155 TaMAPKKK genes under salt stress treatments. Log10-transformed (FPKM + 1) expression values were used to create the heat map. The red or green colors represent the higher or lower relative abundance of each transcript in each sample. Fold change cutoff of two and p-value < 0.05, q-value < 0.05 were taken as statistically significant

Fig. 9.

Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of all TaMAPKKK genes under drought and heat stress treatments. Log10-transformed (FPKM + 1) expression values were used to create the heat map. The red or green colors represent the higher or lower relative abundance of each transcript in each sample. Fold change cutoff of two and p-value < 0.05, q-value < 0.05 were taken as statistically significant

Fig. 10.

Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of all TaMAPKKK genes under cold stress treatments. Log10-transformed (FPKM + 1) expression values were used to create the heat map. The red or green colors represent the higher or lower relative abundance of each transcript in each sample. Fold change cutoff of two and p-value < 0.05, q-value < 0.05 were taken as statistically significant

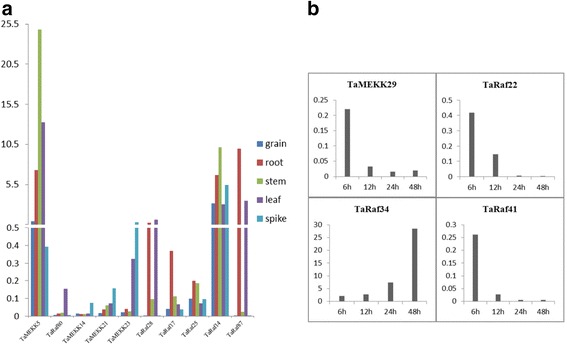

Validation of the expression of TaMAPKKKs by qRT-PCR analysis

Gene expression patterns usually provide the important clue for its function. Though expression profiles analysis based on RNA-seq data, the differentially expressed TaMAPKKKs among different tissues and stresses were obtained. To further verify the expression levels of these TaMAPKKKs, 10 differentially expressed genes in tissues and 4 salt-responsive genes were randomly selected to detect their expression levels through qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 11). Among five tissues, TaMEKK5 was found to be expressed in all tested materials with relatively higher abundance. TaMEKK14, TaMEKK21 and TaMEKK23 were found to show a relatively high expression level in the spike comparing with other four tissues, whereas TaRaf80 exhibited the high abundance in the leaf and TaRaf87 showed high expression levels in root and leaf (Fig. 11a). Under salt stress, TaRaf34 was found to be significantly up-regulated while TaRaf22, TaRaf4 and TaMEKK29 were down-regulated under salt stress condition (Fig. 11b). The qRT-PCR results were highly consistent with that of RNA-seq data, suggesting it is reasonable to use RNA-seq data to assess the expression level of transcripts in wheat and the validated tissues-specific and salt-responsive TaMAKKK provided the candidates for further study of their function in wheat development and stress response.

Fig. 11.

Validation of the expression level of TaMAPKKKs by qRT-PCR analysis. a The relative expression levels of the 10 selected TaMAPKKKs in different tissues; b The relative expression levels of the 4 TaMAPKKKs under salt treatment

Conclusion

This study for the first time identified and characterized the wheat MAPKKK gene family. Through a genome-wide search using the latest available wheat genome information, a total of 155 putative TaMAPKKKs were obtained, which classified into MEKK, ZIK and Raf 3 subfamilies based on the conserved motif signatures. The gene structure, conserved protein domain as well as phylogenetic relationship of these TaMAPKKKs were systematically analyzed and strongly supported the classification. The homologous genes between wheat A, B and D sub-genome and gene duplication were also investigated, which was found to be the main factors contributing to the expansion of wheat MAPKKK gene families. Furthermore, the expression profiles of wheat MAPKKKs during development and under abiotic stresses were investigated and the tissue-specific or stress-responsive TaMAPKKK genes were identified. Finally, 6 tissue-specific and 4 salt-responsive TaMAPKKK genes were selected to validate their expression level through qRT-PCR analysis, which provided the important candidates for further functional analysis of MAPKKK genes in wheat development and stress response. Our current study systematically investigated the genome organization, evolutionary features, regulatory network and expression profiles of the wheat MAPKKK gene family, which not only lay the foundation for investigating the function of these MAPKKKs, but also facilitate to reveal the regulatory and evolutionary mechanism of MAPK cascade involving in growth and development as well as in response to stresses in wheat.

Acknowledgment

This research was mainly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant NO: 31561143005 and 31401373), and partially supported by the 863 program (2012AA10A308) from the Chinese of Ministry of Science & Technology.

Availability of data and material

All of the datasets obtained from the public database and the data supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its Additional files. The phylogenetic data in our manuscript has been deposited into Treebase database with the accession No. S19638. The access URL is http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S19638?x-access-code=e874b0f389ce8519b16789d764348e81&format=html.

Authors’ contributions

NXJ and SWN designed the study and supervised the experiment. WM performed the bioinformatic analysis and prepared the manuscript. YH collected experimental materials. FKW and DPC conducted QPCR analysis. NXJ revised and improved the draft. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competent interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional files

Accession number and samples information of RNA-seq data using in this study. (XLSX 10 kb)

The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR analysis. (XLSX 8 kb)

Cis-regulatory elements found in the promoters of 155 wheat MAPKKK genes. (XLSX 24 kb)

The chromosome position of the identified homologous TaMAPKKK genes and duplicated genes. (XLSX 12 kb)

The detail of 18 TaMAPKKK orthologous genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. (XLSX 10 kb)

Detail information of the network of TaMAPKKK with other wheat genes. (XLSX 42 kb)

FPKM values of the wheat MAPKKK gene in 5 tissues (grain, root, stem, leaf and spike) and under 4 abiotic stresses (drought, salt, heat and cold). (XLSX 34 kb)

Contributor Information

Meng Wang, Email: wm2008xs@163.com.

Hong Yue, Email: yuehongsx@163.com.

Kewei Feng, Email: 791140343@qq.com.

Pingchuan Deng, Email: wangsui519@163.com.

Weining Song, Phone: +86-29-87082984, Email: sweining2002@yahoo.com.

Xiaojun Nie, Phone: +86-29-87082984, Email: small@nwsuaf.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Nishihama R, Banno H, Shibata W, Hirano K, Nakashima M, Usami S, Machida Y. Plant homologs of components of mapk (mitogen-activated protein-kinase) signal pathways in yeast and animal-cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 1995;36(5):749–757. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a078818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez MCS, Petersen M, Mundy J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:621–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiil BK, Petersen K, Petersen M, Mundy J. Gene regulation by MAP kinase cascades. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12(5):615–621. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi Y, Soyano T, Kosetsu K, Sasabe M, Machida Y. HINKEL kinesin, ANP MAPKKKs and MKK6/ANQ MAPKK, which phosphorylates and activates MPK4 MAPK, constitute a pathway that is required for cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51(10):1766–1776. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao FY, Hu F, Zhang SY, Wang K, Zhang CR, Liu T. MAPKs regulate root growth by influencing auxin signaling and cell cycle-related gene expression in cadmium-stressed rice. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2013;20(8):5449–5460. doi: 10.1007/s11356-013-1559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieber JJ, Rothenberg M, Roman G, Feldmann KA, Ecker JR. Ctr1, a negative regulator of the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis, encodes a member of the Raf family of protein-kinases. Cell. 1993;72(3):427–441. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90119-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asai T, Tena G, Plotnikova J, Willmann MR, Chiu WL, Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T, Ausubel FM, Sheen J. MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature. 2002;415(6875):977–983. doi: 10.1038/415977a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danquah A, de Zelicourt A, Colcombet J, Hirt H. The role of ABA and MAPK signaling pathways in plant abiotic stress responses. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(1):40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munnik T, Meijer HJ. Osmotic stress activates distinct lipid and MAPK signalling pathways in plants. FEBS Lett. 2001;498(2-3):172–178. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frye CA, Tang DZ, Innes RW. Negative regulation of defense responses in plants by a conserved MAPKK kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(1):373–378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.1.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar K, Sinha AK. Overexpression of constitutively active mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 6 enhances tolerance to salt stress in rice. Rice. 2013;6(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong XP, Lv W, Zhang D, Jiang SS, Zhang SZ, Li DQ. Genome-wide identification and analysis of expression profiles of maize mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao KP, Richa T, Kumar K, Raghuram B, Sinha AK. In silico analysis reveals 75 members of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene family in rice. DNA Res. 2010;17(3):139–153. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin Z, Wang J, Wang D, Fan W, Wang S, Ye W. The MAPKKK gene family in Gossypium raimondii: genome-wide identification, classification and expression analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(9):18740–18757. doi: 10.3390/ijms140918740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichimura K, Shinozaki K, Tena G, Sheen J, Henry Y, Champion A, Kreis M, Zhang SQ, Hirt H, Wilson C, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: a new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(7):301–308. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill BS, Appels R, Botha-Oberholster AM, Buell CR, Bennetzen JL, Chalhoub B, Chumley F, Dvorak J, Iwanaga M, Keller B, et al. A workshop report on wheat genome sequencing: International Genome Research on Wheat Consortium. Genetics. 2004;168(2):1087–1096. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer KFX, Rogers J, Dolezel J, Pozniak C, Eversole K, Feuillet C, Gill B, Friebe B, Lukaszewski AJ, Sourdille P et al. A chromosome-based draft sequence of the hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) genome. Science. 2014;345(6194):1251788. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Feldman M, Levy AA. Allopolyploidy--a shaping force in the evolution of wheat genomes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;109(1-3):250–258. doi: 10.1159/000082407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berkman PJ, Visendi P, Lee HC, Stiller J, Manoli S, Lorenc MT, Lai K, Batley J, Fleury D, Simkova H, et al. Dispersion and domestication shaped the genome of bread wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2013;11(5):564–571. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nie X, Li B, Wang L, Liu P, Biradar SS, Li T, Dolezel J, Edwards D, Luo M, Weining S. Development of chromosome-arm-specific microsatellite markers in Triticum aestivum (Poaceae) using NGS technology. Am J Bot. 2012;99(9):e369–371. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wicker T, Mayer KF, Gundlach H, Martis M, Steuernagel B, Scholz U, Simkova H, Kubalakova M, Choulet F, Taudien S, et al. Frequent gene movement and pseudogene evolution is common to the large and complex genomes of wheat, barley, and their relatives. Plant Cell. 2011;23(5):1706–1718. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.086629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenchley R, Spannagl M, Pfeifer M, Barker GLA, D’Amore R, Allen AM, McKenzie N, Kramer M, Kerhornou A, Bolser D, et al. Analysis of the breadwheat genome using whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Nature. 2012;491(7426):705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature11650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu CS, Lin CJ, Hwang JK. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins for Gram-negative bacteria by support vector machines based on n-peptide compositions. Protein Sci. 2004;13(5):1402–1406. doi: 10.1110/ps.03479604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Current protocols in bioinformatics. 2002. Chapter 2:Unit 2 3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu ZL, Cavalcanti A, Chen FC, Bouman P, Li WH. Extent of gene duplication in the genomes of Drosophila, nematode, and yeast. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(3):256–262. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong CB, Wang XW, Yu JY, Wu J, Li WS, Huang JY, Dong CH, Hua W, Liu SY. Comprehensive analysis of RNA-seq data reveals the complexity of the transcriptome in Brassica rapa. BMC Genomics. 2013;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Lu K, Guo W, Lu J, Yu H, Qu C, Tang Z, Li J, Chai Y, Liang Y. Genome-wide survey and expression profile analysis of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) gene family in Brassica rapa. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Udvardi MK, Czechowski T, Scheible WR. Eleven golden rules of quantitative RT-PCR. Plant Cell. 2008;20(7):1736–1737. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonak C, Okresz L, Bogre L, Hirt H. Complexity, cross talk and integration of plant MAP kinase signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2002;5(5):415–424. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang M, Wen F, Cao J, Li P, She J, Chu Z. Genome-wide exploration of the molecular evolution and regulatory network of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades upon multiple stresses in Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:228. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Pan C, Wang Y, Ye L, Wu J, Chen L, Zou T, Lu G. Genome-wide identification of MAPK, MAPKK, and MAPKKK gene families and transcriptional profiling analysis during development and stress response in cucumber. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:386. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang G, Lovato A, Polverari A, Wang M, Liang YH, Ma YC, Cheng ZM. Genome-wide identification and analysis of mitogen activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:219. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0219-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao J, Huang JL, Yang YP, Hu XY. Analyses of the oligopeptide transporter gene family in poplar and grape. BMC Genomics. 2011;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Wu J, Wang J, Pan C, Guan X, Wang Y, Liu S, He Y, Chen J, Chen L, Lu G. Genome-wide identification of MAPKK and MAPKKK gene families in tomato and transcriptional profiling analysis during development and stress response. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e103032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altenhoff AM, Studer RA, Robinson-Rechavi M, Dessimoz C. Resolving the ortholog conjecture: orthologs tend to be weakly, but significantly, more similar in function than paralogs. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(5):e1002514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mattick JS. Introns: evolution and function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4(6):823–831. doi: 10.1016/0959-437X(94)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong FL, Wang J, Cheng L, Liu SY, Wu J, Peng Z, Lu G. Genome-wide analysis of the mitogen-activated protein kinase gene family in Solanum lycopersicum. Gene. 2012;499(1):108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J. Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18(6):292–298. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00033-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynch M, Force A. The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics. 2000;154(1):459–473. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.1.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abascal F, Tress ML, Valencia A. The evolutionary fate of alternatively spliced homologous exons after gene duplication. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7(6):1392–1403. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee T, Yang S, Kim E, Ko Y, Hwang S, Shin J, Shim JE, Shim H, Kim H, Kim C, et al. AraNet v2: an improved database of co-functional gene networks for the study of Arabidopsis thaliana and 27 other nonmodel plant species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D996–1002. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oh SA, Allen T, Kim GJ, Sidorova A, Borg M, Park SK, Twell D. Arabidopsis Fused kinase and the Kinesin-12 subfamily constitute a signalling module required for phragmoplast expansion. Plant J. 2012;72(2):308–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hashimoto M, Negi J, Young J, Israelsson M, Schroeder JI, Iba K. Arabidopsis HT1 kinase controls stomatal movements in response to CO2. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(4):391–397. doi: 10.1038/ncb1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu ZN, Lv YX, Zhang M, Liu YP, Kong LJ, Zou MH, Lu G, Cao JS, Yu XL. Identification, expression, and comparative genomic analysis of the IPT and CKX gene families in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp pekinensis). BMC Genomics. 2013;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Qiao L, Zhang X, Han X, Zhang L, Li X, Zhan H, Ma J, Luo P, Zhang W, Cui L, et al. A genome-wide analysis of the auxin/indole-3-acetic acid gene family in hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:770. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choulet F, Alberti A, Theil S, Glover N, Barbe V, Daron J, Pingault L, Sourdille P, Couloux A, Paux E, et al. Structural and functional partitioning of bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science. 2014;345(6194):1249721. doi: 10.1126/science.1249721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pitzschke A, Schikora A, Hirt H. MAPK cascade signalling networks in plant defence. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12(4):421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ichimura K, Casais C, Peck SC, Shinozaki K, Shirasu K. MEKK1 is required for MPK4 activation and regulates tissue-specific and temperature-dependent cell death in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(48):36969–36976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]