ABSTRACT

The rate of maternal influenza vaccination in Korea is much lower than the general population. We evaluated the influenza vaccination rate during pregnancy and assessed women's perceptions of the influenza vaccine. One thousand women of childbearing age were surveyed from April through May 2014, using a questionnaire about vaccination history, general understanding of influenza vaccination and that examined factors that influence decisions about influenza vaccination. We also conducted an intervention to evaluate potential improvement in vaccination behavior. The influenza vaccination rate during pregnancy was 37.3%. The common reasons listed in support of vaccination included the perception of the risk of influenza infection, recommendations from health care providers, and belief in the effectiveness of the influenza vaccine. The most common reasons for not vaccinating included concern about harmful effects and the lack of recommendation from health care providers. Based on the results of the questionnaire and intervention, it is important to provide accurate information and for health care providers to recommend the influenza vaccine to pregnant women. It is also necessary for the government to encourage women to receive the influenza vaccination as a healthcare policy.

KEYWORDS: influenza, vaccination, pregnancy, perception

Introduction

Pregnant women are at high risk of experiencing severe influenza-related complications. Influenza-related morbidity and mortality are higher among pregnant women compared with non-pregnant women,1-3 and influenza infection can also have harmful effects on the fetus, such as stillbirth, neonatal death, preterm delivery, and low birth weight.4 Therefore, it is recommended that pregnant women receive the influenza vaccination at any stage of pregnancy, based on evidence that the influenza vaccine is safe throughout pregnancy and is effective in preventing influenza-related complications.2

According to a 2005 report, influenza vaccination coverage in South Korea in the general population and high-risk groups was 34.3% and 61.3%, respectively.5-7 Although overall influenza vaccination rates were comparable to those in the US and Europe, previous studies have indicated that the maternal influenza vaccination rate is very low in Korea. The seasonal influenza vaccination rate among pregnant Korean women was only 4% during the 2006–2007 influenza epidemic, which was much lower than that of pregnant women in the US (14% in 2004). The influenza vaccination rate among pregnant Korean women increased to 16.4% in 2012, but was still much lower than that of other developed countries; 62% of pregnant US women were vaccinated in 2010 and 57.5% of pregnant UK women in 2012.8,9

As noted in previous studies, misconceptions among pregnant women about the influenza vaccine are a major barrier to vaccination,10,11 and there have been reports that most pregnant Korean women are less likely to be aware of the importance of the influenza vaccine.6,7 However, currently there have been limited efforts to characterize misconceptions and current medical practices are not sufficient to improve education and vaccination rates. Therefore, we evaluated the coverage rate and perceptions of the influenza vaccine in Korean women of childbearing age, and conducted a virtual intervention to increase their intention to receive vaccination.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 1,000 women of reproductive age were enrolled in the study; there were 500 non-pregnant and 500 pregnant women. Among the pregnant women, 264 participants were due prior to October 31, 2014 and there were 236 that were due after October 31, 2014. The median age of the respondents was 33 y old and the mean gestational age in pregnant women was 20.3 ± 10.5 weeks (Table 1). Eighty-one (8.1%) respondents had more than one chronic disease, diabetes mellitus being the most frequently reported.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population (N = 1000).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age groups (years), no. (%) | |

| 25–29 | 150 (15.0) |

| 30–34 | 568 (56.8) |

| 35–39 | 228 (22.8) |

| 40–44 | 54 (5.4) |

| Currently pregnant, no. (%) | 500 (50) |

| Gestational age (wks), mean±SD | 20.3 ± 10.5 |

| Occupation, no. (%) | |

| Full-time housewife | 516 (51.6) |

| Employed | 484 (48.4) |

| Underlying medical conditions, no. (%) | |

| None | 919 (91.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (1.7) |

| Asthma | 14 (1.4) |

| Solid tumor | 13 (1.3) |

| Renal disease | 12 (1.2) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 11 (1.1) |

| Thyroid disease | 11 (1.1) |

| Liver disease | 10 (1.0) |

| Cardiac disease | 5 (0.5) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 4 (0.4) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3 (0.3) |

| Other | 19 (1.9) |

Values are presented as median ± standard deviation, or number (%)

Knowledge of influenza

Participants were presented with 9 ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions about their general knowledge of influenza (Table 2). Most of them correctly answered that, if infected with influenza, pregnant women are at increased risk for a more severe disease course compared to the general population (78.9%) and agreed that influenza vaccination could prevent severe febrile disease and serious complications (77.5%). In contrast, fewer respondents answered that they believe the influenza vaccine is not harmful (57.7%) and that pregnant women are allowed to get the influenza vaccine (60.7%). Only 403 respondents (40.3%) reported that the influenza vaccination benefits neonatal health.

Table 2.

Percentage of correct responses to questions regarding knowledge of influenza (N = 1000).

| Questions | No. (%) of correct responses |

|---|---|

| There are annual influenza outbreaks. | 856 (85.6) |

| When pregnant women get influenza, they are at increased risk for severe disease compared with the general population. | 789 (78.9) |

| When pregnant women get influenza, babies are at increased risk. | 784 (78.4) |

| Influenza vaccination can prevent severe febrile disease and serious complications. | 775 (77.5) |

| Influenza vaccination should be considered every year. | 614 (61.4) |

| Pregnant women are allowed to get the influenza vaccination. | 607 (60.7) |

| Influenza vaccination during pregnancy is harmful. | 577 (57.7) |

| Influenza refers to a severe cold. | 468 (46.8) |

| Influenza vaccination during pregnancy benefits neonatal health. | 403 (40.3) |

Factors that affect vaccination during pregnancy

Among the participants, 764 (non-pregnant women who gave birth within the past 2 y and pregnant women due prior to October 31, 2014) were asked whether they had received an influenza vaccine during their past pregnancy or the past season, and the reasons for vaccination. There were 285 respondents (37.3%) who received the influenza vaccine during pregnancy (Table 3). The common reasons for receiving the influenza vaccine were, in order of descending frequency: perception of the risk of influenza infection and its effects on pregnancy, recommendation from health care providers, and belief in the effectiveness of the influenza vaccine.

Table 3.

Previous experience with influenza vaccination and reasons for vaccination during pregnancy (N = 764).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Influenza vaccination during pregnancy | 285 (37.3) |

| Reason for vaccinationa | |

| Recommendation from healthcare providers | 76 (26.7) |

| Recommendation from a neighbor | 29 (10.2) |

| Media promotion (TV, newspaper and internet) | 15 (5.3) |

| Previous experience of suffering from influenza | 2 (0.7) |

| Perception of risk of influenza infection in pregnant women | 36 (12.6) |

| Perception of risk of influenza infection in babies | 65 (22.8) |

| Poor health | 4 (1.4) |

| Belief in efficacy of the influenza vaccine | 45 (15.8) |

| Previous influenza vaccination experience | 11 (3.9) |

| Other | 2 (0.7) |

| Influenza non-vaccination during pregnancy | 479 (62.7) |

| Reason for non-vaccinationa | |

| Lack of recommendation from healthcare providers | 62 (12.9) |

| Dissuasion by a neighbor | 25 (5.2) |

| Not aware of the necessity of vaccination during pregnancy | 46 (9.6) |

| Believe vaccination is not necessary during pregnancy | 38 (7.9) |

| Lack of time | 27 (5.6) |

| Fear of injection | 11 (2.3) |

| Concerns about adverse reactions | 48 (10.0) |

| Concerns about harmful effects on the fetus | 142 (29.6) |

| Concerns about the efficacy of influenza vaccination during pregnancy | 15 (3.1) |

| Expense | 8 (1.7) |

| Do not normally get a flu shot, regardless of pregnancy | 45 (9.6) |

| Other | 10 (2.1) |

The most important reason was selected by respondents.

Among 764 women, there were 479 (62.7%) respondents who did not receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. The most common reasons for not vaccinating were, in order of descending frequency: concerns about harmful effects on the fetus, adverse reactions, and lack of vaccine recommendation from health care providers (Table 3).

Influenza vaccination during next pregnancy

Among the respondents, 736 (non-pregnant women who gave birth within the past 2 y and pregnant women due after October 31, 2014) were asked about their plans to receive the influenza vaccine during their next pregnancy or upcoming season and reasons for the vaccination (Table 4). The most common reasons for planning to receive the influenza vaccine were the perception of the risk of an influenza infection to the baby, belief in the effectiveness of the influenza vaccination, recommendation from health care providers, and perception of the increased risk of influenza infection in pregnant woman. In contrast, 324 (44.0%) respondents indicated that they would not receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy in the future, because of its harmful effects on the fetus, doubt about the effectiveness of the influenza vaccine, and adverse events.

Table 4.

Future plan and reasons for receiving influenza vaccination during next pregnancy (N = 736).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Plan to receive influenza vaccination during future pregnancya | 412 (56.0) |

| Recommendation from healthcare providers | 66 (16.0)a |

| Perception of risk of influenza infection in pregnant women | 59 (14.3)a |

| Perception of risk of influenza infection in babies | 140 (34.0)a |

| Belief in efficacy of influenza vaccination | 81 (19.7)a |

| Vaccinated during a previous pregnancy | 21 (5.1)a |

| Recommendation from a neighbor | 3 (0.7)a |

| Media promotion (TV, newspaper and internet) | 7 (1.7)a |

| Normally get the influenza vaccine | 7 (1.7)a |

| Previous experience of suffering from influenza | 13 (3.2)a |

| Poor health | 14 (3.4)a |

| Other | 1 (0.2)a |

| Plan not to receive influenza vaccination during future pregnancya | 324 (44.0) |

| Lack of recommendation from healthcare providers | 12 (3.7)a |

| Lack of awareness of the necessity of vaccination during pregnancy | 13 (4.0)a |

| Belief that vaccination is unnecessary during pregnancy | 19 (5.9)a |

| Concerns about the efficacy of influenza vaccination during pregnancy | 51 (15.7)a |

| Concerns about harmful effects on the fetus | 149 (46.0)a |

| Concerns regarding adverse effects | 40 (12.3)a |

| Lack of time | 7 (2.2)a |

| Dissuasion by a neighbor | 15 (4.6)a |

| Fear of injection | 6 (1.9)a |

| Expense | 3 (0.9)a |

| Do not normally get a flu shot, regardless of pregnancy | 10 (3.1)a |

The most important reason was selected by respondents

Changes in future receptiveness after receiving information about the influenza vaccine

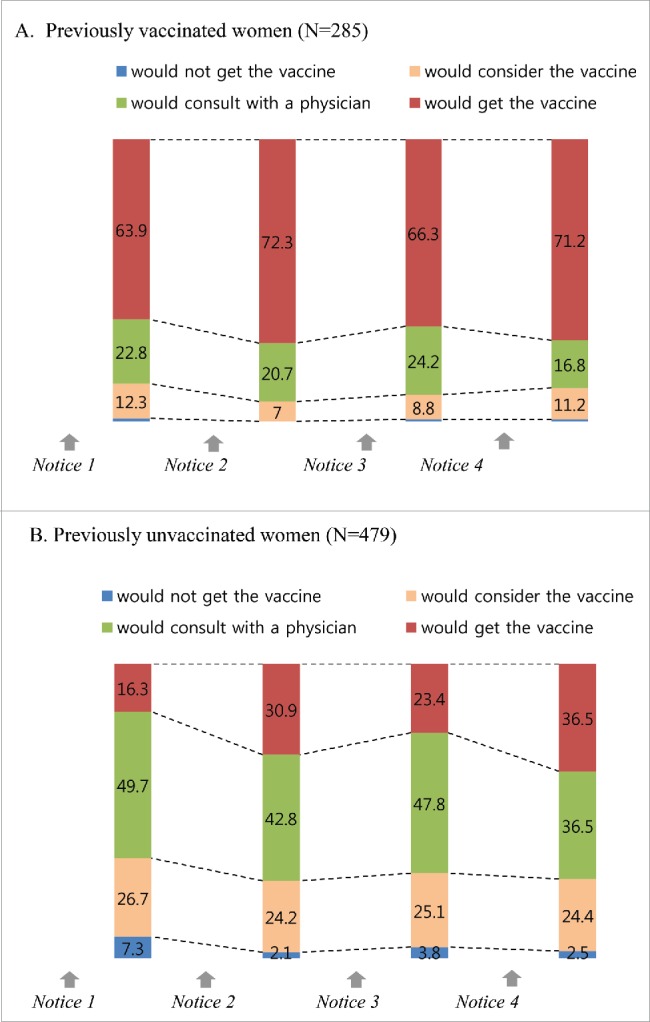

We surveyed 764 participants, as above, and further evaluated potential change in their vaccination behavior after an intervention. The participants received 4 sequential paragraphs and answered questions about their willingness to get the influenza vaccine after reading each paragraph. The first paragraph was about influenza infection risk in pregnant women, the second paragraph was about the benefits of the influenza vaccine in pregnant women and their babies, and the third paragraph was about the safety of the influenza vaccine in pregnant women. After three paragraphs, participants answered whether they would choose to receive the influenza vaccine if the vaccine was offered free of charge by government policy (fourth paragraph). We also compared the difference between the previously vaccinated group and the unvaccinated group.

When they read the first informational paragraph, most participants positively responded that they would choose the influenza vaccine or consider it and consult with a physician; in contrast, 38 (5.0%) respondents answered that they would not receive vaccination. With the second paragraph, the number of participants that indicated that they would get the influenza vaccine increased. Of note, there was a striking increase in the willingness to receive the vaccination among the previously unvaccinated participants, from 16.3% to 30.9% after reading 2 paragraphs (Fig. 1). After the third paragraph, several respondents who had earlier reported that they would have a vaccination retracted their willingness, showing a decrease from 72.3 to 66.3% and from 30.9 to 23.4%. However, after reading the proposed government guarantee, more respondents reported that they would receive vaccination, showing an increase in willingness to be vaccinated.

Figure 1.

Change in future willingness to receive influenza vaccination after intervention regarding the risk of severe disease from influenza during pregnancy (paragraph 1), the effectiveness of the influenza vaccine (paragraph 2), the safety of the influenza vaccine (paragraph 3) and a governmental guarantee (paragraph 4). Numbers in the bars indicate the percentage of subjects in each group.

There were a large number of respondents that were hesitant to get the vaccine, but might potentially receive it. Therefore, we conducted an additional analysis to identify their characteristics, in regards to gestational age, comorbidities, living area, occupation, income, level of education and previous vaccination history. Among them, significant factors included living area, their occupation and previous vaccination history. The results indicated that previously vaccinated women were more likely to receive vaccination (p=0.0009). Women who lived in a province far from Seoul tended to be reluctant to receive the vaccine (p = 0.019) and working mothers were hesitant to receive it compared with full-time mothers (p = 0.001). Interestingly, after the fourth paragraph on government policy, women who lived in the province and those with lower incomes tended to change their willingness to receive vaccination.

Discussion

In 2005, the influenza vaccination rate in Korea was 34.3%, and the rates in high risk groups and persons ≥ 65 years of age were 61.3% and 79.7%, respectively.5 Although those were relatively high, the influenza vaccination rate in pregnant Korean women was much lower than in other developed countries6,7 and this study still showed low coverage rates, which were higher than in 2012.6 In the study, the authors proposed a reason for the high vaccination rate among elderly groups, suggesting that it was associated with government policy.5 In Korea, persons ≥65 years of age are given the influenza vaccine each year free of charge at public health centers between October and December. However, there is currently no healthcare policy to encourage influenza vaccination for pregnant women. There has been an increase in vaccination among pregnant Korean women over recent years, and the rate seems to have increased since 2009. Since the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, public awareness and knowledge about influenza have increased, which has resulted in a gradual increase in vaccination rates. Nonetheless, additional policies and campaigns are needed to further improve influenza vaccination rates, especially in pregnant Korean women. Several studies have emphasized education and healthcare provider recommendations;6,7 however; there have been limited studies evaluating the factors influencing healthcare delivery systems and government policy.Barriers to vaccination are well described within the framework of the Systems Model of Clinical Preventive Care proposed by Walsh and McPhee.12 According to this model, influencing factors for influenza vaccination during pregnancy are classified as predisposing factors (attitudes, concerns about vaccine safety), enabling factors (knowledge, education, physician advice) and health care delivery system/organizational factors (insurance, reimbursement, facilities).11 Factors that improve the willingness of pregnant women to receive vaccination include education and healthcare provider recommendation. In accordance with this model, previous studies reported that misconceptions regarding the influenza vaccine were a significant barrier to vaccination,6,9,13-15 and our study showed that most participants appeared to be poorly informed about the safety and benefits of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. To improve vaccination behavior, education and healthcare provider advice are strongly needed and have been emphasized in the literature. In this study, we provided information about the influenza vaccine to our participants and observed potential improvements in their vaccination behavior. When the participants received information about the importance and effectiveness of the influenza vaccine from the first 2 paragraphs provided, they showed an increased willingness to receive the vaccine. However, throughout this experiment, several participants remained undecided about vaccination, even with knowledge about the reported benefits. An important role in encouraging these pregnant women will be recommendation from health care providers and governmental policy. Within Walsh and McPhee's model,12 the health care delivery system and other organizational factors are also barriers to vaccination during pregnancy. When we suggested that the government could provide the influenza vaccine to pregnant women, approximately half of the participants reported that they would get the influenza vaccine, along with an increased willingness among participants who remained undecided about vaccination. This increase can be explained by the cost effect, although initially the participants reported that they consider the expense less than other factors. Therefore, the last paragraph suggests that the government should become an agent in the vaccine campaign, and we surmise that this suggestion convinced the participants of the legitimacy of vaccination during pregnancy.

There were some limitations to this study. One limitation was a potential selection bias resulting from recruiting participants using an online mailing. Among the participants who received the questionnaire, it is possible that women who were more interested in the influenza vaccine might have eagerly completed it. This could have resulted in an increase in the participation rate of women who were already favorable toward the influenza vaccine, which could have led to bias in the reported vaccination rate. Additionally, there is a further limitation in that we did not measure actual behavior, but intention, which is unpredictable.

In conclusion, the influenza vaccination rate during pregnancy has improved, but remains low. To improve the influenza vaccination rate in pregnant women in Korea, it is important to provide women with accurate information, and health care providers should strongly recommend vaccination. Finally, if the government guaranteed influenza vaccination as a healthcare policy, it could improve vaccination rates among pregnant Korean women.

Materials and methods

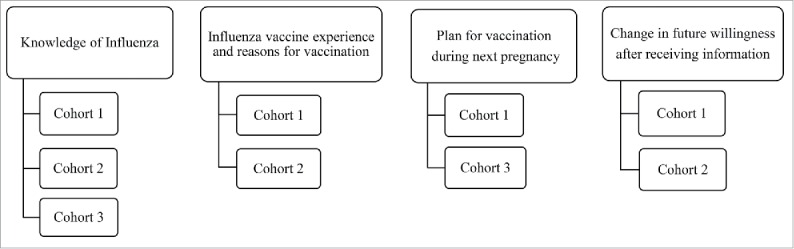

We planned to survey 1,000 women of childbearing age, comprising 500 pregnant and 500 non-pregnant women who had given birth within the last 2 y. We asked a research company (Macromillembrain) to do an online survey using a questionnaire and the study was conducted between April and May 2014. The company selected approximately 10,000 women 20–45 y of age from their panel and sent questionnaires via an email. Among them, 2,970 responded and we enrolled 1,000 women based on their character, including pregnancy and childbirth. We divided the pregnant women into 2 groups, based on birth due date, and selected October 31 which is part of the seasonal influenza vaccination campaign period. In Korea, influenza vaccination is received between October and December, because the influenza season begins annually in December and its peak comes during the following February. We assumed that most pregnant women who expected their babies prior to October 31, 2014 had gone through the previous influenza vaccine season and already received or did not receive the vaccine. In contrast, women that were expecting their babies after October 31, 2014 would not have been pregnant during the previous influenza season and could opt to receive vaccination in the upcoming season. Therefore, we asked the former group about their experience with the influenza vaccine during the past season and asked the latter group about their intention to receive vaccination in the upcoming season. Consequently, this study involves 3 cohorts of women: a cohort of 500 non-pregnant women who had given birth within the previous 2 y (cohort 1); a cohort of pregnant women who were due to give birth before October 31, 2014 (cohort 2); a cohort of pregnant women who were due to give birth after October 31, 2014 (cohort 3). We surveyed the 3 cohorts differentially, using a preformed questionnaire (Fig. 2); we assessed general knowledge about the influenza vaccine in all 3 cohorts, previous experience of influenza vaccination during their past or current pregnancy and reasons for receiving it in 2 cohorts (cohort 1 and 2), and intention to receive the influenza vaccine in their current or next pregnancy in cohorts 1 and 3. Change in future willingness to receive the influenza vaccine was assessed in cohorts 1 and 2 by dissemination of 4 paragraphs and further questions regarding this intervention.

Figure 2.

This study involved 3 cohorts: a cohort of 500 non-pregnant women who had given birth within the previous 2 y (cohort 1); a cohort of pregnant women who were due to give birth before October 31, 2014 (cohort 2); and a cohort of pregnant women who were due to give birth after October 31, 2014 (cohort 3). They were differentially assessed on 4 subjects using a questionnaire.

The questionnaire was designed based on previous studies6,7 and was composed of questions about demographic characteristics (age, pregnancy, pregnancy period and baby due date), knowledge about the influenza vaccine, previous influenza vaccination history, factors that influenced vaccination and non-vaccination, and an influenza vaccination plan for pregnancy. In the end of the questionnaire, we used an intervention to evaluate potential change in willingness to be vaccinated. Four paragraphs were provided that informed the participants about the influenza vaccine and each paragraph had a following set of questions that asked about willingness to get the influenza vaccine during future pregnancy. The four paragraphs can be summarized as follows: (1) Pregnant women are at increased risk of severe disease and death from influenza; the infection may also lead to complications such as stillbirth, neonatal death, preterm delivery and decreased birth weight; (2) Influenza vaccination in pregnancy will protect both pregnant women and their newborns against influenza; (3) Influenza vaccination is safe throughout pregnancy; in previous studies, mothers have not reported any significant vaccine reactions, and no associations between vaccination and delivery complications or poor fetal outcomes have been observed; (4) If the government offered the influenza vaccine free of charge, would you receive it?

The general characteristics of respondents and the differences in perception were analyzed using Chi-square tests. The associations among influenza vaccination-related factors were analyzed with Chi-square tests and Fisher's exact tests. Analyses were run using the statistical program SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA).

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant of the TEPIK (Transgovernmental Enterprise for Pandemic Influenza in Korea) which is a part of Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project by Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No.: A103001).

References

- [1].Omer SB, Goodman D, Steinhoff MC, Rochat R, Klugman KP, Stoll BJ, Ramakrishnan U. Maternal influenza immunization and reduced likelihood of prematurity and small for gestational age births: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2011; 8(5):e1000441; PMID:21655318; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vaccines against influenza. Weekly epidemiological record. 2012; 87(47):461-76; PMID:2321014720308830 [Google Scholar]

- [3].Creanga AA, Johnson TF, Graitcer SB, Hartman LK, Al-Samarrai T, Schwarz AG, Chu SY, Sackoff JE, Jamieson DJ, Fine AD, et al.. Severity of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 115(4):717-26; PMID:20308830; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d57947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rasmussen SA JD, Bresee JS. Pandemic Influenza and Pregnant Women. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008; 14(1):95-100; PMID:18258087; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3201/eid1401.070667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kee SY, Lee JS, Cheong HJ, Chun BC, Song JY, Choi WS, Jo YM, Seo YB, Kim WJ. Influenza vaccine coverage rates and perceptions on vaccination in South Korea. J Infect 2007; 55(3):273-81; PMID:17602750; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.04.354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kim IS, Seo YB, Hong KW, Noh JY, Choi WS, Song JY, Cho GJ, Oh MJ, Kim HJ, Hong SC, et al.. Perception on influenza vaccination in Korean women of childbearing age. Clin Exp Vaccine Res 2012; 1(1):88-94; PMID:23596582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7774/cevr.2012.1.1.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kim M-J, Lee S-Y, Lee K-S, Kim A, Son D, Chung M-H, et al.. Influenza Vaccine Coverage Rate and Related Factors on Pregnant Women. Infect Chemother 2009; 41(6):349-354; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3947/ic.2009.41.6.349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Drees M, Johnson O, Wong E, Stewart A, Ferisin S, Silverman PR, Ehrenthal DB. Acceptance of 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine among pregnant women in Delaware. Am J Perinatol 2012; 29(4):289-94; PMID:22147638; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1055/s-0031-1295660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dexter LJ, Teare MD, Dexter M, Siriwardena AN, Read RC. Strategies to increase influenza vaccination rates: outcomes of a nationwide cross-sectional survey of UK general practice. BMJ open 2012; 2(3); PMID:22581793; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Maher L, Hope K, Torvaldsen S, Lawrence G, Dawson A, Wiley K, Thomson D, Hayen A, Conaty S. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy: coverage rates and influencing factors in two urban districts in Sydney. Vaccine 2013; 31(47):5557-64; PMID:24076176; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Naleway AL, Smith WJ, Mullooly JP. Delivering influenza vaccine to pregnant women. Epidemiol Rev 2006; 28:47-53; PMID:16731574; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/epirev/mxj002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Judith M.E., Walsh SJM. A systems model of clinical preventive care: an analysis of factors influencing patient and physician. Health Educ Quart 1992; 19(2):157-75; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/109019819201900202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Silverman NS, Greif A. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Patients' and physicians' attitudes. J Reprod Med 2001; 46(11):989-94; PMID:11762156 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wallis DH, Chin JL, Sur DK. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy: current practices in a suburban community. J Am Board Fam Pract 2004; 17(4):287-91; PMID:15243017; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3122/jabfm.17.4.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yeager DP, Toy EC, Baker B 3rd. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 1999; 16(6):283-6; PMID:10586981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1055/s-2007-993873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]