Abstract

Objective

Assess the impact of preoperative serum anti-TNFα drug levels on 30-day postoperative morbidity in inflammatory bowel disease patients.

Summary Background Data

Studies on the association of anti-TNFα drugs and postoperative outcomes in IBD are conflicting due to variable pharmacokinetics of anti-TNFα drugs.. It remains to be seen whether preoperative serum anti-TNFα drug levels correlate with postoperative morbidity.

Methods

30 days postoperative outcomes of consecutive IBD surgical patients with serum drawn within 7 days pre-operatively, were studied. The total serum level of 3 anti-TNF-α drugs (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab) was measured, with ≥0.98 µg/ml considered as detected. Data was also reviewed according to a clinical cut off value of 3 µg/ml.

Results

217 patients (123 Crohn’s disease (CD) and 94 ulcerative colitis (UC)) were analyzed. 75 of 150 (50%) treated with anti-TNFα therapy did not have detected levels at the time of surgery. In the UC cohort, adverse postoperative outcomes rates between the undetectable and detectable groups were similar when stratified according to type of UC surgery. In the CD cohort, there was a higher but statistically insignificant rate of adverse outcomes in the detectable vs undetectable groups. Using acut-off level of 3 µg/ml, postoperative morbidity (OR=2.5, p=0.03) and infectious complications (OR=3.0, p=0.03) were significantly higher in the ≥ 3 µg/ml group. There were higher rates of postoperative morbidity (p=0.047) and hospital readmissions (p=0.04) in the ≥ 8 µg/ml compared to < 3 µg/ml group.

Conclusion

Increasing preoperative serum anti-TNFα drug levels are associated with adverse postoperative outcomes in CD but not UC patients.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine playing a central role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Monoclonal antibodies targeting TNFα have revolutionized the management of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)1,2,3. Despite the expanding use of anti-TNFα therapy in IBD, the long term need for surgery may not be significantly reduced4,5. More than one-third of patients do not respond to induction therapy (primary nonresponse), and even among initial responders the response wanes over time in 20% to 60% of patients6.

Among its many actions, TNFα is implicated in regulating cells central to wound healing and protection against infection. For example, TNFα is an important mediator of neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion during the initial phases of inflammation7. Experimental studies have also demonstrated that TNFα blockade is associated with significant alterations in wound healing8,9. Patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy have an increased risk of opportunistic infections with various bacterial and mycotic infections10,11,12. Given its potential impact on wound healing and immunosuppressive properties, a crucial concern is whether patients undergoing major abdominal surgery after anti-TNFα drug exposure are at increased risk of early postoperative complications.

Studies reporting on the association of preoperative infliximab therapy use and postoperative outcomes in IBD have been published with conflicting results13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. These variable findings are attributed to a number of factors including retrospective study design, single institution experiences, dissimilar durations of anti-TNFα therapies, difficulty in controlling for disease severity, and the overlapping effect of other immunosuppressive medications, especially corticosteroids. In addition, differing time periods between the last anti-TNFα therapy infusion and date of surgery has plagued all prior studies22.

Rather than the medical history of anti-TNFα agents use, a more accurate measure of anti-TNFα effect in the IBD patient is the absolute serum anti-TNFα drug level at the time of the operation. Increasing evidence demonstrates that despite standardized dosing, varying pharmacokinetics profiles between patients leads to a wide variation in serum anti-TNFα drug levels and by extension, clinical response. Trough infliximab levels are known to be associated with increased rates of remission, lower C-reactive protein (CRP) and improved endoscopic outcomes23,24. We postulate that serum anti-TNFα drug levels may have an adverse surgical impact on IBD patients. Therefore, our study aims to evaluate the association of serum anti-TNFα drug levels with the risk of early postoperative complications in a cohort of IBD patients.

Methods

Study Population

Consecutive UC and CD adult patients undergoing major abdominal surgery by a single surgeon in a tertiary referral center over a 13-year period ending October 2012 were initially identified. From this group, patients who had stored serum drawn within the 7 days period before surgery comprised the study cohort. Patients with IBD-unclassified (IBDU) were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included patients in whom insufficient serum was available for analysis and IBD patients who had anorectal surgery only. This study was approved by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB #30095).

Assessment of Clinical Characteristics

A prospectively maintained IBD registry of patient’s clinical profiles including demographics and disease characteristics was retrospectively reviewed. Demographic information included patient gender, age at time of surgery, pre-operative morbidity and smoking history. Disease characteristics included type of IBD (UC or CD), type of preoperative medication use, abscesses at the time of surgery and indication for surgical intervention (medically-refractory disease vs. dysplasia/cancer). The diagnosis of UC or CD was based upon standard clinical, endoscopic, radiologic and when necessary, pathological criteria25. Medical therapy recorded before IBD-related surgery included steroids (intravenous or oral), immunomodulators (6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, methotrexate or cyclosporine) and anti-TNFα agents (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab). Laboratory values (hemoglobin, serum albumin and C-reactive protein) within one month of surgery were also collated.

Surgical Procedures

The index surgery for UC patients was either a two-stage ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA), or a subtotal colectomy (STC) (as part of a three-stage IPAA) or total proctocolectomy (TPC) with ileostomy. A standard IPAA procedure was performed with complete mucosectomy, ileal J-pouch creation and a temporary diverting ileostomy. The decision to perform an initial STC/TPC or IPAA as the index operation was at the discretion of the operating surgeon. Reasons for STC/TPC included toxic megacolon and/or bowel perforation or patients in whom an IPAA was not technically feasible (for example, significant intra-abdominal obesity or where the tissues were found intra-operatively to be too ‘fragile’ to safely stretch a potential ileal pouch into the pelvis). These criteria reflect current standard of surgical practice widely used by colorectal surgeons operating on UC patients26,27.

In CD patients, the type of surgical procedure selected by the surgeon was dependent on the disease site and surgical indication. In addition, surgical approach in all CD patients was guided by a desire for maximal bowel length conservation.

Serum anti-TNFα Drug Level Measurements

Stored frozen serum samples were used for analysis. Laboratory measurements of serum anti-TNFα drug levels did not degrade over time or with multiple freeze-thaw cycles28,29. Serum anti-TNFα drug levels were measured using the homogenous mobility shift assay, which utilizes high performance liquid phase chromatography (Prometheus Labs, Inc., San Diego, California)30,31. This assay measures the total serum level of all 3 anti-TNFα agents commonly used in IBD (infliximab, adalimumab and certolizumab). The serum anti-TNFα drug levels measurement’s false-positive rate is 5%, with the cut point value of 0.98 µg/ml, as referenced by Prometheus Lab.

Patients were categorized into detectable levels (serum anti-TNFα drug levels more than or equal to 0.98 µg/ml) or undetectable levels (serum anti-TNFα drug levels less than 0.98 µg/ml) groups. The detectable level group was further stratified into low (≥0.98 to <3 µg/ml), medium (≥ 3 to < 8 µg/ml) and high (≥ 8 µg/ml) subgroups.

Postoperative outcomes were also analyzed according to a level of 3 µg/ml, currently the most commonly utilized cut off value for clinical efficacy32. All assays were performed by Prometheus Labs blinded to patients’ clinical characteristics, disease type, and surgery outcomes. Similarly, the records of the postoperative outcomes were analyzed without knowledge of patients’ serum anti-TNFα drug levels.

Early Postoperative Outcomes

Postoperative morbidity and mortality were prospectively recorded during the 30-day period beginning from the date of surgery using inpatient medical records and office chart notes. In patients undergoing planned multi-staged procedures, only the complications arising from the initial surgery were analyzed. A complication was defined as any deviation from the normal expected postoperative course33. These complications were classified as either medical or surgical, and were further characterized as being either minor (grade 1) or major (grade 2 and 3) according to the established Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications34. In addition, all infectious complications, whether surgical or medical in nature, were specifically examined. Postsurgical length of hospitalization and 30-day hospital readmission rates were also noted.

Statistical Analysis

All data were prospectively entered in a standardized database computer program (Microsoft Excel, Seattle, WA). Descriptive statistics were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, frequencies for categorical variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test and continuous variables analyzed with Students’ t-test or one-way ANOVA. A Cochrane-Armitage trend analysis was also used to investigate the relationship between increasing serum anti-TNFα drug levels and postoperative outcomes. Factors found significant on univariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression model to test the effect of confounding variables. Analysis was performed using R statistical computing software. A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

IBD Study Cohort

From December 1999 to October 2012, 217 (21%) patients satisfied study entry criteria and comprised the study cohort (Table 1). The mean age of the study cohort was 36.9 years (standard deviation, 15.5). 57% of the study cohort had CD. Anti-TNFα agents were used before surgery in 65% of the study cohort, most commonly infliximab. Almost 20% of patients had been treated with multiple courses of anti-TNFα agents before surgery. The majority of operations were performed for medical intractability. A small bowel/ileocolic resection (for CD) or an IPAA or STC (for UC) were performed in 93% of the study cohort.

Table 1.

Study Cohort Clinical Characteristics and Serum anti-TNFα Drug Levels

| Study Cohort (n=217) |

Undetectable Level (n=150) |

Detectable Level (n=67) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) | 36.9 (15.5) | 36.6 (15) | 37.4 (16.7) | 0.74 |

| Gender (M : F) | 127 : 90 | 82 : 68 | 45 : 22 | 0.09 |

| Active Smoker at Time of Surgery | 12 (6) | 8 (5) | 4 (6) | 0.85 |

| Type of IBD | ||||

| Crohn’s disease | 123 (57) | 73 (49) | 50 (75) | 0.0005 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 94 (43) | 77 (51) | 17 (25) | |

| Preoperative Steroids | 116 (53) | 69 (46) | 47 (70) | 0.001 |

| Preoperative Immunomodulators | 201 (93) | 137 (91) | 64 (95) | 0.28 |

| 6-mercaptopurine | 138 (64) | 91 (61) | 47 (70) | 0.18 |

| Azathioprine | 15 (7) | 13 (9) | 2 (3) | 0.15 |

| Methotrexate | 22 (10) | 13 (9) | 9 (13) | 0.29 |

| Cyclosporine | 26 (12) | 20 (13) | 6 (9) | 0.36 |

| Preoperative anti-TNFα Agent | 143 (66) | 76 (51) | 67 (100) | 0.006 |

| Infliximab | 79 (36) | 43 (29) | 36 (54) | 0.0005 |

| Adalimumab | 18 (8) | 9 (6) | 9 (13) | 0.07 |

| Certolizumab | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (3) | 0.66 |

| Multiple | 41 (19) | 21 (14) | 20 (30) | 0.007 |

| Indication for Surgery | ||||

| Medical intractability | 189 (87) | 130 (87) | 59 (88) | 0.78 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess at surgery | 15 (7) | 8 (5) | 7 (10) | 0.18 |

| Dysplasia/cancer | 13 (6) | 12 (8) | 1 (1) | 0.10 |

| Mean Preoperative Lab Values | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.93 (1.92) | 11.83 (1.92) | 12.12 (1.93) | 0.36 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.81 (0.65) | 3.78 (0.64) | 3.86 (0.67) | 0.51 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 2.27 (3.41) | 2.23 (3.49) | 2.35 (3.29) | 0.84 |

| Surgical Procedures | ||||

| Small bowel / ileocolic resection | 108 (50) | 65 (43) | 43 (64) | 0.005 |

| Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis | 52 (23) | 45 (30) | 7 (10) | 0.003 |

| Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy | 43 (20) | 32 (21) | 11 (16) | 0.40 |

| Low colorectal anastomosis | 10 (5) | 4 (3) | 6 (9) | 0.06 |

| Closure of ileostomy / colostomy | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0.60 |

| Total proctocolectomy/ ileostomy | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0.60 |

| Pelvic Anastomosis Created | 62 (29) | 49 (33) | 13 (19) | 0.048 |

All values in parentheses denote % except age and preoperative lab values (standard deviation) IBD inflammatory bowel disease

Serum anti-TNFα Drug Level Profile

82% (177 out of 217) of the serum samples were drawn on the day of the surgery. Sixty-seven study cohort patients (31%) had detectable serum anti-TNFα drug levels (Table 1). Mean level in the detectable group was 18.17 ± 19.95 µg/ml (median 10.94, range, 1.53 to 99.11 µg/ml). There were no significant differences in age and gender distribution between the undetectable and detectable groups. Detectable levels were significantly more common in CD versus UC patients (OR 3.1; 95% CI 1.6–5.9; p=0.0005) and patients also being treated with steroids (OR 2.8; 95% CI 1.5–5.1; p=0.001). Although there was a significant association between the use of anti-TNFα agents and detection of serum anti-TNFα drug levels (p=0.001), 75 of the 142 (53%) patients with a history of anti-TNFα therapy did not have a detectable level at the time of surgery.

The detectable group included low, medium and high serum anti-TNFα drug levels, with 66% of the serum values in the high group (≥ 8 µg/ml) (Table 2). Although there was no significant association noted between levels and a single anti-TNFα agent use, patients treated with multiple courses of different anti-TNFα agents more commonly had high serum anti-TNFα drug levels. Significantly higher preoperative hemoglobin and albumin levels were noted in the high serum anti-TNFα drug level group compared to the low serum anti-TNFα drug level group.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Different Detectable Serum anti-TNFα Drug Levels

| Low Level (n=6) |

Medium Level (n=17) |

High Level (n= 44) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) | 32.2 (19.2) | 40.1 (17.1) | 37.1 (16.3) | 0.60 |

| Gender M:F | 3 : 3 | 13 : 4 | 29 : 15 | 0.46 |

| Type of IBD | ||||

| Crohn’s disease | 3 (50) | 12 (71) | 35 (79) | 0.23 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 3 (50) | 5 (29) | 9 (21) | |

| Preoperative Steroids | 3 (50) | 12 (70) | 32 (73) | 0.58 |

| Preoperative Immunomodulators | ||||

| 6-mercaptopurine | 5 (83) | 9 (53) | 33 (75) | 0.23 |

| Azathioprine | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.57 |

| Methotrexate | 1 (17) | 1 (6) | 7 (16) | 0.53 |

| Cyclosporine | 2 (33) | 1 (6) | 3 (7) | 0.12 |

| Preoperative anti-TNFα Agent | ||||

| Infliximab alone | 5 (83) | 10 (59) | 21 (48) | 0.27 |

| Adalimumab alone | 1 (17) | 5 (29) | 3 (7) | 0.06 |

| Certolizumab alone | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.57 |

| Multiple | 0 | 1 (6) | 19 (43) | 0.003 |

| Mean Preoperative Lab Values | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 10.7 (0.97) | 10.9 (1.98) | 12.7 (1.75) | 0.004 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.6 (0.34) | 3.42 (0.73) | 4.0 (0.62) | 0.03 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 5.72 (2.03) | 2.94 (4.03) | 1.76 (2.91) | 0.05 |

| Indication for Surgery | ||||

| Medical intractability | 6 (100) | 15 (88) | 38 (86) | 1.0 |

| Abscess at time of surgery | 0 | 1 (6) | 6 (14) | 0.83 |

| Dysplasia/cancer | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 | 0.34 |

| Surgical Procedures | ||||

| Small bowel/ ileocolic resection | 3 (50) | 12 (71) | 30 (68) | 0.62 |

| Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis | 2 (33) | 2 (12) | 3 (7) | 0.10 |

| Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy | 1 (17) | 4 (24) | 6 (14) | 0.67 |

| Low colorectal anastomosis | 0 | 1 (6) | 5 (11) | 1.0 |

| Closure of ileostomy/colostomy | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Total proctocolectomy/ileostomy | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Pelvic Anastomosis Created | 2 (33) | 3 (18) | 8 (18) | 0.71 |

All values in parentheses denote % except age and preoperative lab values (standard deviation)

IBD inflammatory bowel disease

Serum anti-TNFα drug levels and clinical characteristics of the UC and CD patients are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Although 60 out of 94 (64%) patients in the UC cohort were treated with preoperative anti-TNFα therapy, only 17 (28%) had detectable serum anti-TNFα drug levels at the time of surgery. In the UC cohort, the mean detectable serum anti-TNFα drug level was 14.00 ± 16.21 µg/ml. There were proportionately equal numbers of UC patients who underwent a 2-stage IPAA vs. 3-stage IPAA in both the detectable and undetectable groups. In the CD cohort, although 83 patients were treated with preoperative anti-TNFα therapy, only 50 (60%) had detected serum anti-TNFα drug levels at the time of surgery. Mean serum anti-TNFα drug level was 19.58 ± 21.03 µg/ml. Significantly more patients in the undetectable group had a small bowel/ileocolic resection compared to the detectable group (p=0.02). The incidence of intra-abdominal abscess found intra-operatively was similar between both groups.

Table 3.

UC Patient Cohort Clinical Characteristics and Serum anti-TNFα Drug Levels

| UC Cohort (n = 94) |

Undetectable Level (n = 77) |

Detectable Level (n =17) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) | 38.4 (15.9) | 37.2 (14.38) | 43.8 (21.52) | 0.12 |

| Gender M: F | 45 : 49 | 34 : 43 | 11 : 6 | 0.59 |

| Indication for Surgery | ||||

| Medical Intractability | 81 (86) | 67 (87) | 14 (82) | 0.13 |

| Dysplasia/Cancer | 13 (14) | 10 (13) | 3 (18) | |

| Type of Surgery | ||||

| 3-Stage (STC as index operation) | 42 (45) | 32 (41) | 10 (59) | 0.20 |

| 2-Stage (IPAA as index operation) | 52 (55) | 45 (59) | 7 (41) | |

| Mean Preoperative lab values | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.6 (1.7) | 11.6 (1.8) | 11.6 (1.6) | 0.90 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.7) | 0.75 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 2.0 (3.9) | 2.2 (4.2) | 1.0 (2.4) | 0.42 |

| Preoperative Steroids | 17 (18) | 13 (17) | 4 (24) | 0.50 |

| Preoperative Immunomodulators | ||||

| 6-mercaptopurine | 31 (33) | 27 (35) | 4 (23) | 0.41 |

| Azathiopurine | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 0 | 1.00 |

| Methotrexate | 6(6) | 6 (8) | 0 | 0.59 |

| Cyclosporine | 25 (26) | 19 (25) | 6 (35) | 0.38 |

| Preoperative anti-TNFα agent | 60 (64) | 43 (56) | 17 (100) | 0.02 |

All values in parentheses denote % except preoperative lab values (standard deviation)

UC ulcerative colitis; STC subtotal colectomy; IPAA ileal pouch-anal anastomosis

Table 4.

CD Patient Cohort Clinical Characteristics and Serum anti-TNFα Drug Levels

| CD Cohort (n = 123) |

Undetectable Level (n = 73) |

Detectable Level (n = 50) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Behavior | ||||

| Stricturing | 62 (50) | 37 (51) | 25 (50) | 0.94 |

| Penetrating | 24 (19) | 15 (20) | 9 (18) | 0.72 |

| Both | 25 (20) | 12 (16) | 13 (26) | 0.20 |

| Non-stricturing/penetrating | 12 (10) | 9 (12) | 3 (6) | 0.25 |

| Intra-abdominal Abscess | 15 (12) | 8 (11) | 7 (14) | 0.47 |

| Small Bowel/ileocolic Resection | 85 (69) | 56 (77) | 29 (58) | 0.02 |

| Mean Preoperative Lab Values | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 12.2 (2.0) | 12.1 (2.0) | 12.3 (2.0) | 0.66 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.9 (0.61) | 3.9 (0.56) | 3.9 (0.67) | 0.84 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 2.45(3.11) | 2.26 (2.84) | 2.67 (3.42) | 0.53 |

| Preoperative Steroids | 99 (80) | 56 (77) | 43 (86) | 0.21 |

| Preoperative Immunomodulators | ||||

| 6-mercaptopurine | 75 (61) | 41 (56) | 34 (68) | 0.24 |

| Azathiopurine | 12 (10) | 10 (14) | 2 (4) | 0.09 |

| Methotrexate | 16 (13) | 7 (10) | 9 (18) | 0.18 |

| Cyclosporine | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0.65 |

| Preoperative anti-TNFα Agent | 83 (67) | 33 (45) | 50 (100) | 0.0008 |

All values in parentheses denote % except preoperative lab values (standard deviation)

Influence of Serum anti-TNFα Drug Levels on Early Postoperative Complications

Postoperative complications in the study cohort were noted in a total of 68 patients, representing an overall rate of 31% (Table 5). The most common postoperative complication was ileus (n = 16). Included in the 19 major surgical complications were small bowel obstruction (3/8 in the detectable group), postoperative intra-abdominal abscess (5/7 in the detectable group), anastomotic leaks (2/2 in the undetectable group), evisceration (1 in the detectable group) and intra-abdominal hemorrhage (1 in the undetectable group). The majority of infectious complications in the study cohort are surgical related (19/30 with superficial and/or intra-abdominal infections). The only death was a 32-year-old CD patient (serum anti-TNFα drug level of 3.47 µg/ml) who developed a fatal pulmonary embolism on postoperative day one after an elective laparoscopic total colectomy. Although there was an increased rate of medical and infectious complications in the detectable vs undetectable serum anti-TNFα drug level groups, these differences did not reach statistical significance (18% vs 9%, 19% vs 11%). In addition, although there was an increasing incidence of overall surgical complication rates and readmission rates with increasing serum anti-TNFα drug levels, these trends did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5.

Postoperative Outcomes and Serum anti-TNFα Drug Levels in Study Cohort

| Study Cohort (n=217) |

Undetectable Level (n=150) |

Detectable Level (n=67) |

Low Level (n=6) |

Medium Level (n=17) |

High Level (n=44) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative morbidity | 68 (31) | 44 (29) | 24 (36) | 1 (17) | 7 (41) | 16 (36) |

| Medical complications | 26 (12) | 14 (9) | 12 (18) | 1 (17) | 5 (29) | 6 (14) |

| Major | 11 (5) | 5 (3) | 6 (9) | 0 | 4 (24) | 2 (4) |

| Minor | 15 (7) | 9 (6) | 6 (9) | 1 (17) | 1 (6) | 4 (9) |

| Surgical complications | 51 (24) | 36 (24) | 15 (22) | 0 | 3 (18) | 12 (27) |

| Major | 19 (9) | 13 (9) | 6 (9) | 0 | 2 (12) | 4 (9) |

| Minor | 32 (15) | 23 (15) | 9 (13) | 0 | 1 (6) | 8 (18) |

| Infectious complications | 30 (14) | 17 (11) | 13 (19) | 1 (17) | 3 (18) | 9 (20) |

| Postoperative mortality | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Mean postoperative LOS (d) | 5.6 (2.5) | 5.8 (2.6) | 5.2 (2.2) | 5.3 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.9) | 5.4 (2.4) |

| Readmission within 30 days | 32 (15) | 20 (13) | 12 (18) | 0 | 3 (18) | 9 (20) |

All values in parentheses denote % except postoperative length of stay (standard deviation)

LOS length of stay

All p=

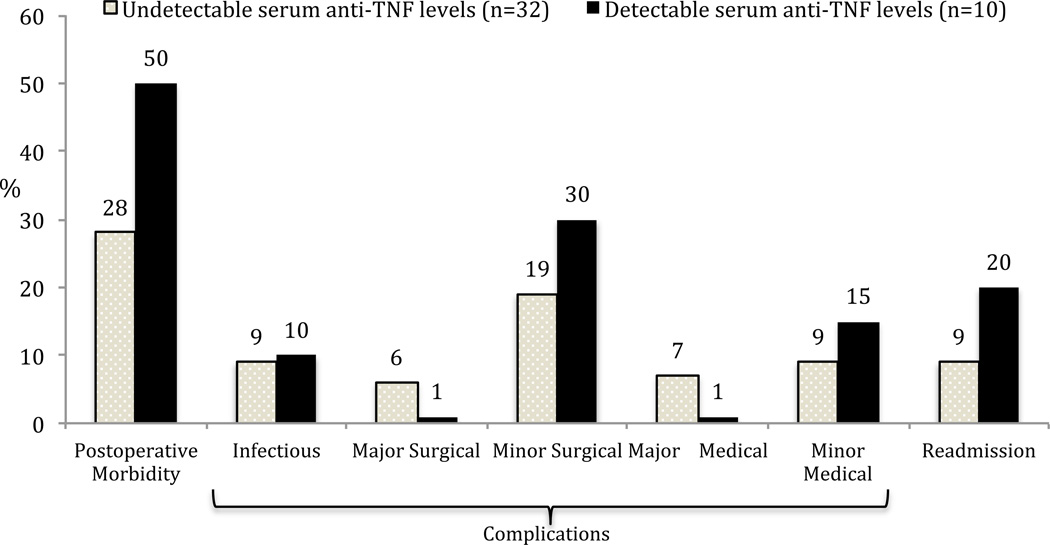

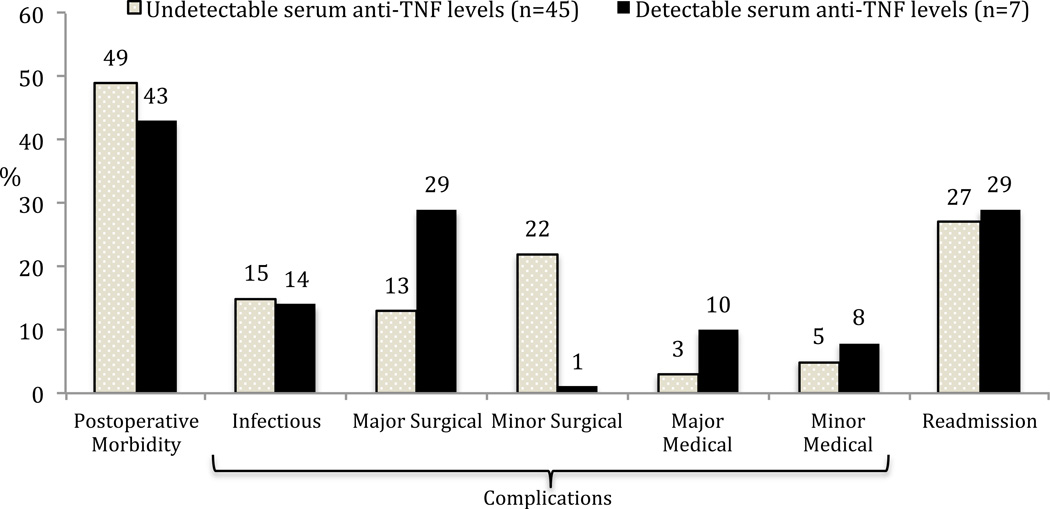

There were no significant differences in adverse postoperative outcomes between the detectable and undetectable serum anti-TNFα drug level groups in the entire UC cohort (Table 6) or in UC patients stratified according to type of index surgery (Figures 1 and 2). Similar results were also seen with outcomes analyzed according to a serum cut off level of 3 µg/ml (data not shown). Analyzing a subgroup of UC patients with a preoperative history of anti-TNFα agent use (n = 60), the infectious complication risk between the undetectable group (n = 43) and the detectable serum anti-TNFα drug level groups (n =17) was not significantly different (4/43 vs 2/17, 9% vs 12%, p = 0.78). Overall postoperative morbidity risk (17/43 vs 8/17, 40% vs 47%, p = 0.59) and readmissions (8/43 vs 4/17, 19% vs 24%, p = 0.67) were also not significantly different.

Table 6.

Postoperative Outcomes and Serum anti-TNFα Drug Levels in UC Cohort

| UC Cohort (n=94) |

Undetectable Level (n=77) |

Detectable Level (n=17) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative morbidity | 39 (41) | 31 (40) | 8 (47) | 0.61 |

| Medical complications | 11 (12) | 8 (10) | 3 (18) | 0.41 |

| Major | 4 (4) | 3 (4) | 1 (6) | 0.72 |

| Minor | 7 (7) | 5 (6) | 2 (12) | 0.46 |

| Surgical complications | 29 (31) | 24 (31) | 5 (29) | 1.00 |

| Major | 10 (11) | 8 (10) | 2 (12) | 0.87 |

| Minor | 19 (20) | 16 (21) | 3 (18) | 0.77 |

| Infectious complications | 12 (13) | 10 (13) | 2 (12) | 0.89 |

| Mean postoperative LOS (d) | 6.3 (2.1) | 6.3 (2.1) | 6.0 (2.3) | 0.54 |

| Readmission within 30 days | 19 (20) | 15 (19) | 4 (23) | 0.71 |

All values in parentheses denote % except postoperative length of stay (standard deviation)

LOS length of stay

Figure 1.

Postoperative outcomes and serum anti-TNFα drug levels in ulcerative colitis patients undergoing subtotal colectomy or total proctocolectomy/end-ileostomy (all p=NS).

Figure 2.

Postoperative outcomes and serum anti-TNFα drug levels in ulcerative colitis undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (all p=NS).

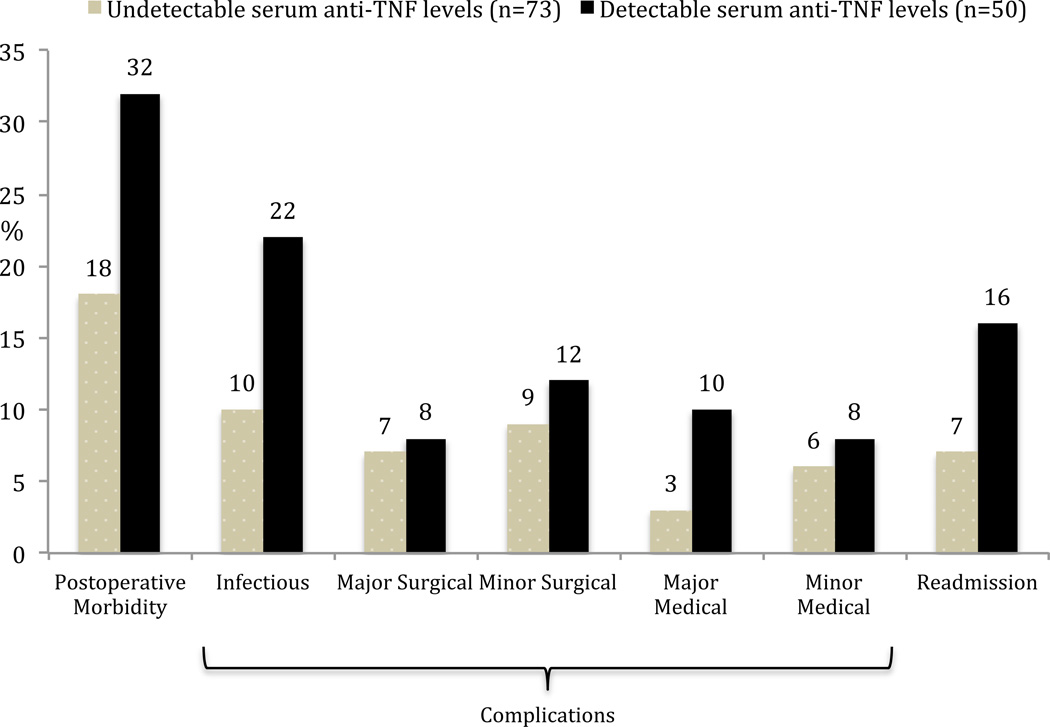

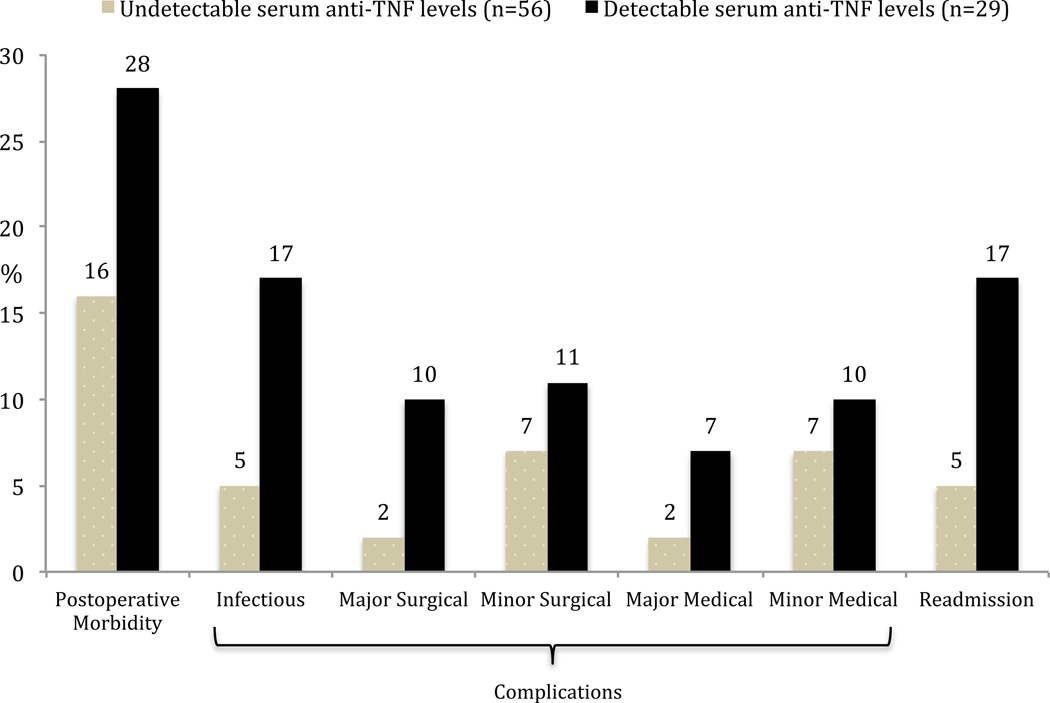

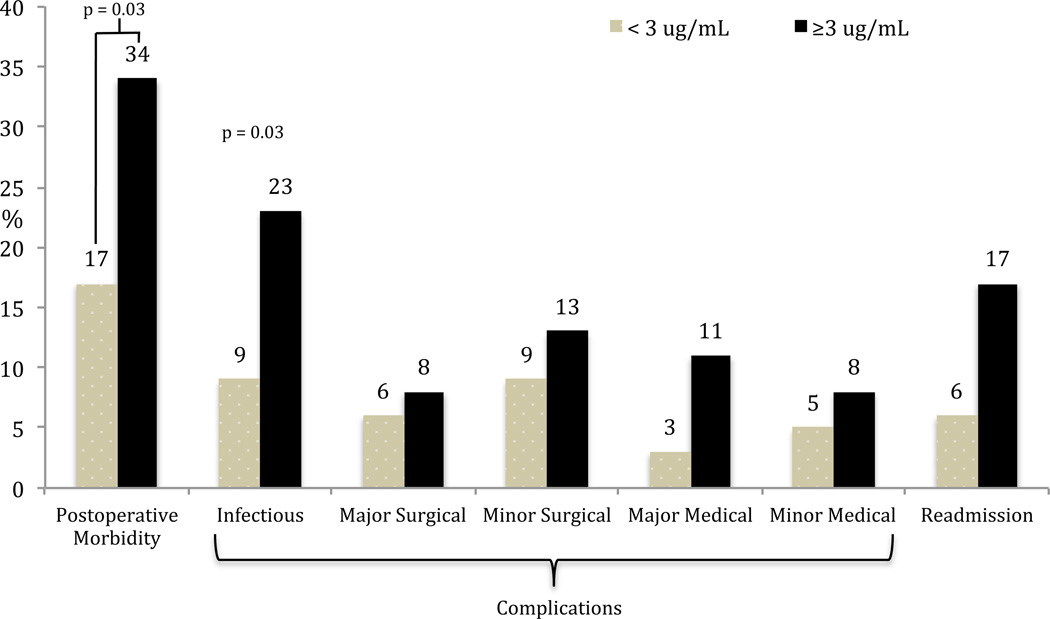

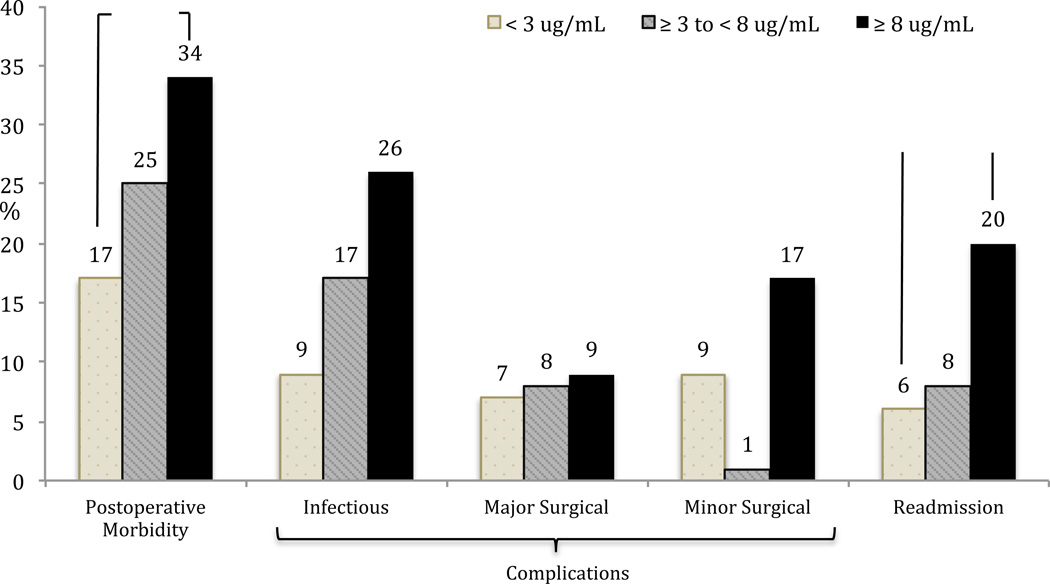

In the CD cohort, there was a higher rate of overall postoperative morbidity, infectious complications and readmissions in the detectable serum anti-TNFα drug level group (Figure 3). None of these trends however reached statistical significance. As the majority of operations performed in the CD group were small bowel/ileocolic resections, the outcomes were also analyzed in this subgroup. Again, there was a higher but statistically insignificant higher rate of overall postoperative morbidity, infectious complications and readmissions in patients with detectable serum anti-TNFα drug levels (Figure 4). Using a clinical cut-off serum anti-TNFα drug level of 3 µg/ml, both overall postoperative morbidity (16/47 vs 13/76; OR=2.5, 95% CI 1.07–5.85, p = 0.03) and infectious complications (11/47 vs 7/76; OR=3.0, 95% CI 1.08–8.43, p = 0.03) were significantly higher in the ≥ 3 µg/ml group (Figure 5). There was a significantly higher rate of overall postoperative morbidity (p = 0.047) and readmissions (p = 0.043) in the ≥ 8 µg/ml serum anti-TNFα drug level group compared to the < 3 µg/ml serum anti-TNFα drug level group (Figure 6). However, a Cochrane Armitage trend analysis did not demonstrate significant results.

Figure 3.

Postoperative outcomes and serum anti-TNFα drug levels in Crohn’s disease patients (all p=NS).

Figure 4.

Postoperative outcomes and serum anti-TNFα drug levels in Crohn’s disease patients undergoing small bowel/ileocolic resection (all p=NS)

Figure 5.

Postoperative outcomes in Crohn’s disease and serum anti-TNFα drug level cut off value at 3 µg/ml. There was a proportionately higher rate of overall postoperative morbidity and infectious complications in the ≥ 3 µg/ml serum anti-TNFα drug level group compared to the < 3 µg/ml serum anti-TNFα drug level group.

Figure 6.

Postoperative outcomes in Crohn’s disease patients with increasing serum anti-TNFα drug levels. There was a proportionately higher rate of overall postoperative morbidity and readmissions in the ≥ 8 µg/ml serum anti-TNFα drug level group compared to the < 3 µg/ml serum anti-TNFα drug level group.

In our CD cohort, as there was a significantly higher incidence of overall postoperative morbidity and infectious complications in the ≥ 3 µg/ml group on univariate analysis, we then focused on whether these results held true when we adjusted for the important confounding factors such as preoperative steroids, immunomodulators and albumin. Using a multivariable logistic regression model, the effect of adding additional confounding variables was tested. Paired comparisons of ≥ 3 µg/ml serum anti-TNFα drug levels with steroids, 6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine showed that the association of ≥ 3 µg/ml serum anti-TNFα drug levels remained significant for overall postoperative morbidity and infectious complications when adjusting for these confounders. However, these serum levels did not remain significantly associated with postoperative morbidity when adjusted for albumin (Table 7). There were no statistically significant risks for adverse postoperative outcomes in association with immunomodulator use, steroid use or laboratory levels (data not shown).

Table 7.

Model Analysis of Postoperative Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease Patients using Multivariate Logistic Regression and Serum anti-TNFα Drug Level Cut-off Value of 3 µg /ml

| Overall Postoperative Morbidity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

P value |

|

| 1. | Serum anti-TNFα drug level ≥ 3 µg/ml | 2.41 | 1.03 – 5.68 | 0.04 |

| Steroids alone | 1.47 | 0.45 – 4.82 | 0.53 | |

| 2. | Serum anti-TNFα drug level ≥ 3 µg/ml | 2.52 | 1.07 – 5.92 | 0.03 |

| 6-Mercaptopurine alone | 0.95 | 0.39 – 2.29 | 0.91 | |

| 3. | Serum anti-TNFα drug level ≥ 3 µg/ml | 2.45 | 1.04 – 5.78 | 0.04 |

| Azathioprine alone | 0.78 | 0.16 – 3.91 | 0.76 | |

| 4. | Serum anti-TNFα drug level ≥ 3 µg/ml | 1.91 | 0.66 – 5.51 | 0.23 |

| Albumin alone | 0.42 | 0.18 – 0.99 | 0.05 | |

| Infectious Complications | ||||

| 1. | Serum anti-TNFα drug level ≥ 3 µg/ml | 2.86 | 1.01 – 8.08 | 0.04 |

| Steroids alone | 1.79 | 0.37 – 8.6 | 0.46 | |

| 2. | Serum anti-TNFα drug level ≥ 3 µg/ml | 3.34 | 1.16 – 9.57 | 0.02 |

| 6-Mercaptopurine alone | 0.5 | 0.17 – 1.41 | 0.19 | |

| 3. | Serum anti-TNFα drug level ≥ 3 µg/ml | 2.92 | 1.03 – 8.26 | 0.04 |

| Azathioprine alone | 0.66 | 0.08 – 5.71 | 0.71 | |

| 4. | Serum anti-TNFα drug level ≥ 3 µg/ml | 3.03 | 0.82 – 11.21 | 0.09 |

| Albumin alone | 0.63 | 0.24 – 1.65 | 0.35 | |

Discussion

This study represents the first to specifically examine the impact of preoperative anti-TNFα drug levels on postoperative outcomes in IBD patients. A comprehensive literature review yielded a subgroup analysis in one retrospective case-control study that looked at postoperative outcomes in 19 IBD patients with preoperative serum infliximab levels35. Ten patients had detectable serum levels of infliximab and nine patients had undetectable infliximab levels. There were no differences in overall infectious complication rates between the two groups. Wound infections were more frequent in the group with detected infliximab (30% vs. 0%) although the results were not statistically significant and this was a small study. As there are many studies correlating clinical and endoscopic responses in IBD with anti-TNFα drug levels and recognizing the potential for adverse wound healing and serious infections with anti-TNF-α therapy usage36,37, evaluation of the association between levels and early postoperative complications represents a logical step in IBD surgical research.

The observation that over one-half of patients treated with anti-TNFα therapy before surgery did not have detectable levels at the time of surgery was intriguing. The half-life of infliximab demonstrates a wide range from 7 to 18 days38,39. Marked inter-individual differences in drug pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity lead to differences in observed clinical efficacy despite standardized dosing40. The poor correlation between preoperative anti-TNFα therapy use and detectable levels in our study also demonstrates that merely using a medication record of anti-TNFα drug exposure is not rigorous enough as a factor for analysis in postoperative morbidity studies. Existing studies on the effect of anti-TNFα therapy on early postoperative complications in IBD patients demonstrate a wide disparity in the timing of drug infusion to surgery date. A recent meta-analysis on anti-TNFs and postoperative complications in IBD included prior studies with infliximab infusions varying from 4 to 12 weeks before surgery41. Conflicting results from these studies may in part reflect different anti-TNFα drug levels at the time of surgery.

There was a higher proportion of UC patients compared to CD patients in the undetectable serum anti-TNFα drug level group. UC disease-specific factors might stimulate earlier formation of immune complexes in anti-TNFα agent treated UC patients and lead to a reduction in serum infliximab levels24. This effect appears to be largely dependent on the severity of disease as a larger volume of inflamed intestinal surface leads to increased drug clearance42. This observation might explain the overall poorer clinical response to anti-TNFα in hospitalized vs. ambulatory UC patients43,44,45.

Significant associations were noted between a number of laboratory values and serum anti-TNFα drug levels in this surgical cohort. Notably, mean hemoglobin and albumin levels trended higher and CRP trended lower with increasing drug levels. Anemia in IBD can be a result of the inhibitory effects of cytokines such as TNFα on erythropoiesis and as such an improvement in hemoglobin levels is expected following anti-TNFα therapy46,47. Hepatic synthetic function and nutritional status are also known to improve with clinical response to anti-TNFα therapy, as reflected in our study’s laboratory values48. A decrease in CRP levels is seen with increasing anti-TNFα drug levels secondary to anti-TNF blockade on the inflammatory cascade49. It is possible the associations between these laboratory values and anti-TNFα drug levels could favorably influence the purported deleterious effects anti-TNFα therapy have on early postoperative outcomes.

Some surgeons advocate that UC patients exposed to anti-TNF drug therapy in the preoperative period should undergo a three-stage rather than two-stage IPAA; the first operation would be a STC and end ileostomy, allowing the patient to be withdrawn from anti-TNFα therapy before creation of a ileal pouch. This surgical approach is supported by two studies showing UC patients exposed to anti-TNFα agents were significantly more likely to have postoperative anastomotic leak and pelvic infections after IPAA14,18. Other UC studies, including a recent meta-analysis, however have found no such association20,21,50,51. The variable results noted in all these studies may reflect that they are all retrospective, patients are undergoing varying percentages of two-stage and three-stage IPAA, and are not uniformly based on a single surgeon experience resulting in variations in surgical techniques confounding postoperative outcomes. Additionally, as these studies included varying anti-TNFα drug dosing and intervals between dosing and surgery, the diverse results may reflect differing serum anti-TNFα drug levels between patients. In our UC cohort, there was no significant difference in adverse postoperative outcomes between the undetectable and undetectable serum anti-TNFα drug level groups. In addition, we analyzed the STC/TPC group and the IPAA group separately in order to standardize our results according to the complexity of UC surgery performed. The results again showed no significant disparity, even when patients were stratified according to a clinical cut off value at 3 µg/ml. Measurements of anti-TNFα drug levels may not have a role in the prognostication of postoperative morbidity in UC patients. More importantly though, the lack of effect of serum anti-TNFα drug levels on patients undergoing two-stage IPAA suggests that a universal policy of using a three-stage IPAA in anti-TNFα exposed patients espoused by some surgeons may be unnecessary.

The use of anti-TNFα therapy can simply be a surrogate marker for more severe disease and inherently sicker UC patients. It is plausible that undetected serum anti-TNFα drug levels in this group represent treatment failure due to the higher inflammatory disease burden, and that it is the severity of the underlying disease rather than the medications per se that potentially contribute to worse surgical outcomes. With this in mind, we looked at subgroup analysis of postoperative outcomes in undetected vs. detected serum anti-TNFα drug levels in UC patients exposed to anti-TNFα therapy only. No significant differences in outcomes were seen between groups.

In our CD group, overall postoperative morbidity and infectious complications were significantly higher in the ≥ 3 µg/ml group compared to the < 3 µg/ml group. Our data also demonstrated a significantly increased overall postoperative morbidity and readmissions with levels ≥ 8 µg/ml. Taken together, these results suggest that rising values of serum anti-TNFα drug levels are associated with adverse postoperative outcomes in this population set. Our findings confirm and extend the observations from a prior study in our institution that analyzed the association between prior anti-TNFα therapy use and postoperative morbidity in 458 CD patients52. A recent meta-analysis of eight studies in CD patients also indicated that preoperative infliximab treatment was associated with an increased risk of postoperative infectious complications, and a trend towards an increased risk of both noninfectious and overall complications41.

There were many factors that account for differences in morbidity outcomes between our UC and the CD groups. The type of surgical procedure was a crucial consideration. For example, all our UC patients who underwent a pelvic anastomosis have temporary protective stomas and this surgical factor would have minimized the adverse sequelae of anastomotic leaks and/or pelvic sepsis. The proportion of patients with detectable serum anti-TNFα drug levels in the UC group was also much lower than in the CD group. Finally, our CD patients frequently had additional risk factors for adverse surgical outcomes such as multiple intra-abdominal fistulae, multiple bowel anastomoses, past surgeries, and urgent indications for surgery.

Limitations of this study are a lack of adjustment for disease severity in UC patients, steroid dosage, nutritional deficiency such as body mass index and disease duration prior to operation, all of which might be predictive of developing postsurgical morbidity53,54. We also do not have accurate information on the time period from date of last anti-TNFα drug dosage to the date of surgery. As this is a study spanning over 12 years, improved surgical technique and postoperative care such as the introduction of enhanced recovery pathways may have impacted our results. We also have no prospective information on surgery-specific factors such as intraoperative operating time and blood loss. It still remains unknown whether these factors could have confounded our results or whether such factors differ among anti-TNFα therapy exposed and unexposed patients. Lastly, our results reflect the experience of a single high-volume tertiary referral center and thus may not be generalizable to other settings.

The challenge that surgeons face is the balance between the timing of surgical intervention and preoperative anti-TNFα therapies’ perceived infectious risk profile. Our series is the first study to date specifically looking at the relationship between serum anti-TNFα drug levels and early surgical complications. There is an association of increasing preoperative levels and postoperative infectious outcomes for CD patients but not UC patients. Although our study results need to be validated, the potential surgical practice-changing implications of this study suggest that especially among CD patients, preoperative serum anti-TNFα drug levels measurement should be considered to optimize preoperative counseling, guide surgical practice and determine surgical prognosis. For example, a surgeon may elect to wait for the drug serum wash out period in elective CD surgery. Lastly, a blanket policy of advocating 3 stage procedures for all anti-TNFα-treated UC patients may be unfounded.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Podium presentation at Digestive Disease Week, Orlando, FL, May 21, 2013.

References

- 1.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. ACCENT I Study Group. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9317):1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawson MM, Thomas AG, Akobeng AK. Tumour necrosis factor alpha blocking agents for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD005112. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005112.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Oussalah A, Williet N, et al. Impact of azathioprine and tumour necrosis factor antagonists on the need for surgery in newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2011;60:930–936. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.227884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713–1725. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1102942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):52–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulich TE, del Castillo J, Keys M, et al. Kinetics and mechanisms of recombinant human interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced changes in circulating numbers of neutrophils and lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1987;139:3406–3415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee R, Efron D, Udaya T, et al. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha attenuates wound breaking strength in rats. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8:547–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albina J, Mastrofrancesco B, Vessella J, et al. HIF-1 expression in healing wounds: HIF-1alpha induction in primary inflammatory cells by TNF-alpha. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1971–C1977. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Vidal C, Rodriguez-Fernandez S, Teijon S, et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in infliximab-treated patients: the importance of screening in prevention. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:331–337. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0628-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein GR, Cohen RD, Feagan BG, et al. Safety of infliximab and other Crohn’s disease therapies: treat (TM) registry data with a mean of 5 years of follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S773-S. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al. Early postoperative complications are not increased in patients with Crohn’s disease treated perioperatively with infliximab or immunosuppressive therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:878–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mor IJ, Vogel JD, da Luz Moreira A, et al. Infliximab in ulcerative colitis is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1202–1207. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchal L, D’Haens G, van Assche G, et al. The risk of post-operative complications associated with infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease: a controlled cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:749–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunitake H, Hodin R, Shellito PC, et al. Perioperative treatment with infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis is not associated with an increased rate of postoperative complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1730–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0630-8. discussion 1730–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schluender SJ, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky M, et al. Does infliximab influence surgical morbidity of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis? Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1747–1753. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvasekar CR, Cima RR, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Harrington JR, Harmsen WS, Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ, Wolff BG, Pem-berton JH. Effect of infliximab on short-term complications in patients undergoing operation for chronic ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:956–962. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.044. discussion 962–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appau KA, Fazio VW, Shen B, Church JM, Lashner B, Remzi F, 37 Brzezinski A, Strong SA, Hammel J, Kiran RP. Use of infliximab within 3 months of ileocolonic resection is associated with ad- verse postoperative outcomes in Crohn's patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1738–1744. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrante M, D’Hoore A, Vermeire S, Declerck S, Noman M, Van Assche G, Hoffman I, Rutgeerts P, Penninckx F. Corticosteroids but not infliximab increase short-term postoperative infectious complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1062–1070. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z, Wu Q, Wang F, Wu K, Fan D. Meta-analysis: effect of preoperative infliximab use on early postoperative complications in patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing abdominal surgery. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:922–928. doi: 10.1111/apt.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali Tauseef, Yun Laura, Rubin David T. Risk of post-operative complications associated with anti- TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Jan 21;18(3):197–204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maser EA, Villela R, Silverberg MS, Greenberg GR. Association of trough serum infliximab to clinical outcome after scheduled maintenance treatment for Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1248–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seow CH, Newman A, Irwin SP, et al. Trough serum infliximab: a predictive factor of clinical outcome for infliximab treatment in acute ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2010;59(1):49–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.183095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein CN, Fried M, Krabshuis JH, et al. World Gastroenterology Organization Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of IBD in 2010. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010;16:112–124. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen JL, Strong SA, Hyman NH, et al. Practice parameters for the surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1997–2009. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metcalf AM. Elective and emergent operative managements of ulcerative colitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGuyer C. Infliximab and Antibodies to Infliximab (ATI) Measurement-- 27222, 2012. New York, NY: Clinical Laboratory Evaluation Program (CLEP), New York State Department of Health Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGuyer C. Adalimumab and Antibodies to Adalimumab (ATA) determination (AnserADA) -35169, 2013. New York, NY: Clinical Laboratory Evaluation Program (CLEP), New York State Department of Health Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang SL, Ohrmund L, Hauenstein S, et al. Development and validation of a homogeneous mobility shift assay for the measurement of infliximab and antibodies-to-infliximab levels in patient serum. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2012;382(1–2):177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauenstein S, Ohrmund L, Salbato J, et al. Comparison of homogeneous mobility shift assay and solid-phase ELISA for the measurement of drug and anti-drug antibody (ADA) levels in serum from patients treated with anti-TNF biologics. Presented at Digestive Disease Week; May 19–22, 2012; San Diego, California. Abstract Su1928. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feagan BG, Singh S, Lockton S, et al. Novel infliximab (IFX) and antibody-to infliximab (ATI) assays are predictive of disease activity in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(Suppl.1):S-565. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clavien P, Sanabria J, Strasberg S. Proposed classification of complication of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dindo Daniel, et al. Classification of Surgical Complications: A New Proposal With Evaluation in a Cohort of 6336 Patients and Results of a Survey. Ann Surg. 2004 Aug;240(2):205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waterman M, Wei Xu, Dinani A, et al. Preoperative biological therapy and short-term outcomes of abdominal surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62:387–394. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. Arthritis Care Res. 5. Vol. 64. Hoboken: 2012. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis; pp. 625–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grijalva CG, Chen L, Delzell E, et al. Initiation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists and the risk of hospitalization for infection in patients with autoimmune diseases. JAMA. 2011;306(21):2331–2339. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klotz U, Teml A, Schwab M. Clinical pharmacokinetics and use of infliximab. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46:645–660. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200746080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ternant D, Aubourg A, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, et al. Infliximab pharmacokinetics in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2008;30:523–529. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e318180e300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bendtzen K, Ainsworth M, Steenholdt C, et al. Individual medicine in inflammatory bowel disease: monitoring bioavailability, pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity of anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha antibodies. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(7):774–781. doi: 10.1080/00365520802699278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kopylov U, Ben-Horin S, Zmora O, et al. Anti-tumor Necrosis Factor and Postoperative Complications in Crohn’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2404–2413. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ordas I, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Therapeutic drug monitoring of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1079–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Regueiro M, Curtis J, Plevy S. Infliximab for hospitalized patients with severe ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:476–481. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Järnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-Liby I, et al. Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1805–1811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gisbert JP, Gonzalez-Lama Y, Mate J. Systematic review: Infliximab therapy in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(1):19–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergamaschi G, Sabatino A, Alvertini R, et al. Prevalence and pathogenesis of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Influence of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α treatment. Haematologica. 2010 Feb;95(2):199–205. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.009985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doyle Mittie K, Rahman Mahboob U, et al. Treatment with infliximab plus methotrexate improves anemia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis independent of improvement in other clinical outcome measures—A Pooled Analysis from three large, multicenter, double-blind, randomized clinical trials. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;39:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Olson A, et al. Serum albumin concentration: a predictive factor of infliximab pharmacokinetics and clinical response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48:297–308. doi: 10.5414/cpp48297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elliott MJ, Maini RN, Feldmann M, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with chimeric monoclonal antibodies to tumor necrosis factor alpha. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1681–1690. doi: 10.1002/art.1780361206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gainsbury ML, Chu DI, Howard LA, et al. Preoperative infliximab is not associated with an increased risk of short-term postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:397–403. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eshuis EJ, Al Saady RL, Stokkers PC, et al. Previous infliximab therapy and post-operative complications after proctocolectomy with ileum pouch anal anastomosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lau CC, Dubinsky M, Melmed G, et al. Su1133 Influence of Biologic Agents on Short-Term Postoperative Complications in Patients With Crohn's Disease: A Prospective, Single-Surgeon Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 144.5(2013):S-407. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kasparek MS, Bruckmeier A, Beigel F, et al. Infliximab does not affect postoperative complication rates in Crohn’s patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1207–1213. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coquet-Reinier B, Berdah SV, Grimaud JC, et al. Preoperative infliximab treatment and postoperative complications after laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: a case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1866–1871. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]