Abstract

Background

Infantile hemangiomas (IH) are the most common soft-tissue tumors of infancy, but little is known regarding their true incidence.

Objectives

To determine the current incidence of IH and examine trends in incidence, demographics, and lesion characteristics over three decades.

Methods

The Rochester Epidemiology Project was used to identify infants residing in Olmsted County, Minnesota, who were diagnosed with IH between January 1, 1976 and December 31, 2010.

Results

Nine hundred and ninety-nine infants were diagnosed with IH. Incidence increased over the 3- decade study period from 0.97 per 100 person-years to 1.97 per 100 person years (p<0.001). Average gestational age at birth and birth weight for infants with IH decreased over the study period (39.2 to 38.3 weeks, p<0.001 and 3383 to 3185 grams, p=0.003, respectively). The overall age- and sex-adjusted incidence of IH was 1.64 per 100 person-years (95% CI 1.54–1.75).

Limitations

The population of Olmsted County is predominantly non-Hispanic white, limiting our ability to report racial differences in incidence. This was a retrospective study.

Conclusions

This study provides a longitudinal, population-based incidence of IH. Incidence has increased steadily over the past three decades, correlating significantly with decreasing gestational age at birth and birth weight in affected infants.

INTRODUCTION

Few reports of the true incidence of infantile hemangiomas (IH) exist, with prior estimates varying from 3 to 10%1, 2. While generally benign and self-limited, hemangiomas can lead to significant complications including disfigurement, pain, and functional impediment3.

Early estimates of incidence are difficult to interpret due to flaws in methodology, including referral bias, inadequate duration of follow-up, and inconsistency in classification of vascular birthmarks. Nomenclature of vascular anomalies became standardized only after Mulliken and Glowacki proposed a biological classification schema in 19824.

The few studies published since the introduction of this classification vary in their estimates of incidence. An Australian study found the incidence to be 2.6%, but relied on reporting of IH by parents and followed infants only through 6 weeks of age5. An American prospective study of 594 infants followed through 9 months of age found the incidence to be 4.5%6. This study was limited by the low number of IH identified (27 infants), and reliance on telephone follow-up and parental reporting to identify lesions that developed after birth6. A recent, large, cross-sectional study of the Dutch population found a prevalence of IH of 9.9% in children aged 0–16 months7. Practitioners were instructed on the use of the Mulliken classification of cutaneous vascular anomalies prior to diagnosis of these patients, thus providing an accurate estimate of prevalence of IH in this population. Although informative, prevalence cannot be directly compared to incidence.

Risk factors for the development of IH including female sex, white non-Hispanic race, prematurity, low birth weight, and multiple gestation have been well-described1, 7–10. Placental abnormalities, chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis have also been associated with IH6, 7, 9, 11. Prematurity rates and associated complications have increased in the US over the past decades, but how these changes relate to incidence of IH is unknown.

Our objective was to determine the current incidence of IH in Olmsted County, Minnesota (MN), as well as trends in incidence, demographics, and phenotypic data related to IH over the past three decades.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Patient Selection

In this institutional review board-approved study, the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) was used to identify 1,547 children aged 0–3 years, who were residents of Olmsted County, MN, at the time of diagnosis of ‘hemangioma skin’ between January 1, 1976 and December 31, 2010. The REP is a unique medical records linkage system allowing for access to records for nearly all patient encounters in Olmsted County, MN, since the 1960s. This resource provided a means to identify all diagnosed cases of IH in a geographically-defined community, thus enabling accurate calculation of incidence. The potential for the REP database to be utilized in a population-based study has been previously described12.

A review of each medical record was performed by the primary authors. Diagnosis of IH was determined to be accurate if the lesion demonstrated characteristic morphology via reported physical examination findings and/or appropriate growth characteristics with initial growth out of proportion to the child, followed by slow involution. When available, photographs were reviewed. Lesions that were found to have a description or photograph inconsistent with a diagnosis of IH were excluded. Fifteen patients declined research authorization during the data-gathering phase of the study and were excluded. Those with diagnosis after age 1 year were excluded as they were less likely to have a lesion description and clinical course consistent with IH. Incidence date was defined by first physician diagnosis date.

Demographic data and maternal pregnancy complication(s) (if present) were extracted from the medical record. Pregnancy complications were defined as potentially pathologic processes associated with pregnancy documented in the infant’s medical record, including, but not limited to: multiple gestation, diabetes/gestational diabetes, hypertension (preexisting or pregnancy-induced), preeclampsia/eclampsia, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count), maternal infection, substance abuse, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Extracted IH characteristics included type (superficial, deep, combined, or not specified), number, size at time of diagnosis, distribution (focal, multiple, segmental, or not specified), location(s), presence of associated syndromes, and complications. IH complications identified from review of the medical record included bleeding, ulceration, infection, disfigurement, visual axis obstruction, airway involvement, feeding impairment, or other functional impediment. For each patient, the date/age of diagnosis, age at referral (if present), and treatment method (if present) was identified.

Statistical Methods

Continuous features were summarized with means, standard deviations (SDs), medians, and ranges; categorical features were summarized with frequency counts and percentages. Associations of features with year of diagnosis, gestational age, and birth weight were evaluated using Spearman rank correlation coefficients and Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Incidence rates per 100 person-years were calculated using incident cases of IH as the numerator and age- and sex-specific estimates of the population of Olmsted County, Minnesota as the denominator. The denominators were obtained from a complete enumeration of the Olmsted County population provided by the REP13. Because the population of Olmsted County is predominantly white, incidence rates were directly age- and sex-adjusted to the structure of the 2010 US white population. The relationships of sex and year of diagnosis (grouped as 1976–1980, 1981–1985, 1986–1990, 1991–1995, 1996–2000, 2001–2005, and 2006–2010) with incidence rates of IH were assessed by fitting Poisson regression models using the SAS procedure GENMOD. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All tests were two-sided and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Population

Nine hundred ninety-nine children less than 1 year of age and diagnosed with IH were identified in Olmsted County, Minnesota between January 1, 1976 and December 31, 2010. Sixty-four percent were female. Of the patients with documented race (N=924), 837 (91%) were non-Hispanic white (Table I). Mean gestational age at birth (N=957) was 38.7 weeks, range 25.4 – 42.6 weeks. Eighty-five percent of girls were full-term (37+ weeks) compared with 84% of boys (p=0.98). Mean birth weight (N=988) was 3276 grams, range 705–5080 grams.

Table I.

Summary of features for incident cases of infantile hemangioma; N=999

| Feature | Number (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Female | 644 (64) |

| Male | 355 (36) |

|

| |

| Race (N=924)* | |

| White | 837 (91) |

| Non-white | 87 (9) |

|

| |

| Type of hemangioma(s)* | |

| Not specified | 672 (67) |

| Superficial | 200 (20) |

| Deep | 80 (8) |

| Combined | 70 (7) |

|

| |

| Distribution of hemangioma(s)* | |

| Not specified | 24 (2) |

| Focal | 752 (75) |

| Segmental | 14 (1) |

| Multifocal | 212 (21) |

|

| |

| Number of lesions (N=996) | |

| 1 | 769 (77) |

| 2 | 144 (14) |

| 3 | 42 (4) |

| 4 | 16 (2) |

| ≥5 | 25 (3) |

|

| |

| Complication | |

| No | 889 (89) |

| Yes | 110 (11) |

|

| |

| Syndrome | |

| No | 989 (99) |

| Yes | 10 (1) |

|

| |

| Type of syndrome* | |

| Spinal dysraphism | 1 (<1) |

| Visceral hemangioma | 3 (<1) |

| Other | 7 (1) |

|

| |

| Treatment | |

| No | 917 (92) |

| Yes | 82 (8) |

Patient could be listed in more than one group.

Forty-four percent of patients had IH on the head/neck, 38% on the trunk, 33% on extremities, and 6% in the genital/perineal region. In cases where IH sub-type was reported or identifiable (N=350), 57% were superficial, 23% were deep, and 20% were combined. Fourteen patients (1%) were identified to have segmental IH. Multiple IH (>1 hemangioma) were identified in 23% of patients, though only 25 patients (3%) had ≥5 lesions (Table I). Infants with low birth weight or premature birth were more likely to have >1 IH (p<0.001 and p=0.017, respectively).

The overall complication rate was 11%. Bleeding was the most common complication at 6% of the total cohort, followed by ulceration (5%), other (including disfigurement, visual axis obstruction, feeding impairment, or other functional impediment) (3%), infection (2%), and airway involvement (1%). Presence of an IH- related syndrome was uncommon (1%). Twenty-seven percent of patients were referred to one or more subspecialists, most commonly dermatologists at 17% of the total cohort, followed by plastic surgeons (5%) and ophthalmologists (4%). Other subspecialists included general surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, otorhinolaryngologists, and hematologists. Eight percent (8%) of patients underwent treatment of the IH. Surgical removal was the most common form of treatment (4% of total cohort), followed by corticosteroid injection (2%), pulsed-dye laser (2%), oral corticosteroid (1%), topical corticosteroid (1%), other treatment (1%), oral beta-blocker (<1%), and topical beta-blocker (<1%).

Thirty percent had a reported maternal pregnancy complication, most commonly, multiple gestation (7% of the total cohort), followed by diabetes or gestational diabetes (5%), hypertension (3%), and tobacco use (3%).

Age- and Sex-Specific Incidence of IH

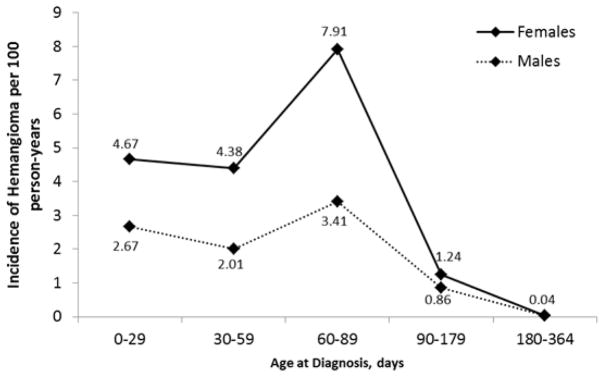

The overall age- and sex-adjusted incidence of IH over the entire study period was 1.64 per 100 person-years (95% CI 1.54–1.75). Age-adjusted incidence was 2.20 per 100 person-years (95% CI 2.03–2.37) for girls compared with 1.11 per 100 person-years (95% CI 1.00–1.23) for boys (p<0.001). Mean age at diagnosis was 2.7 months, range 0 – 11.8 months (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Incidence of Infantile Hemangioma (Females versus Males).

Temporal Trends in Incidence and Characteristics of IH

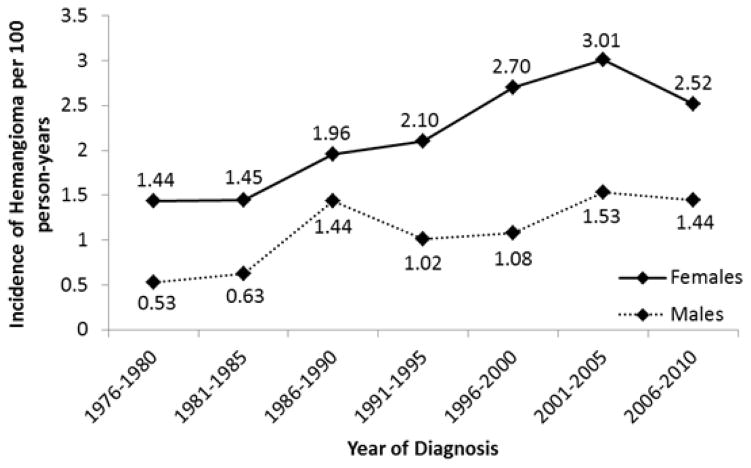

Incidence rates of IH increased over the 35-year period from 0.97 per 100 person-years to 1.97 per 100 person years (p<0.001). Incidence peaked during the years 2001–2005 at 2.25 per 100 person-years (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in Incidence of Infantile Hemangioma (Olmstead County, Minnesota 1976–2010).

Demographic data and clinical features of IH were compared by year of diagnosis (Table II). For these comparisons, year of diagnosis was grouped as 1976–1990, 1991–2000, and 2001–2010. Female-to-male ratio did not vary significantly between time intervals. Percentage of non-white patients was noted to increase, likely to due to diversification of the population of Olmsted County over this time interval. The average number of lesions increased from 1.3 to 1.6 (p<0.001).

Table II.

Comparison of features by year of diagnosis; N=999

| 1976–1990 | 1991–2000 | 2001–2010 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=300 | N=288 | N=411 | ||

|

| ||||

| Feature | Mean (Median) | P-value | ||

| Age at diagnosis (months) | 3.0 (2.1) | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.5 (2.1) | 0.40 |

| Gestational age (weeks; N=957) | 39.2 (39.3) | 38.6 (39.0) | 38.3 (39.1) | <0.001 |

| Birth weight (grams; N=988) | 3383 (3380) | 3294 (3343) | 3185 (3320) | 0.003 |

| Age at referral (months; N=265) | 7.8 (6) | 8.3 (5) | 5.2 (3) | <0.001 |

| Number of lesions (N=996) | 1.3 (1) | 1.6 (1) | 1.6 (1) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Feature | Number (%) | P-value | ||

|

| ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 187 (62) | 195 (68) | 262 (64) | 0.79 |

| Male | 113 (38) | 93 (32) | 149 (36) | |

|

| ||||

| Race (N=924)* | ||||

| White | 259 (97) | 250 (92) | 328 (85) | <0.001 |

| Non-white | 7 (3) | 21 (8) | 59 (15) | |

|

| ||||

| Gestational age (weeks; N=957) | ||||

| ≥37 | 247 (90) | 234 (83) | 324 (81) | 0.003 |

| 34–36.85 | 22 (8) | 35 (12) | 46 (12) | |

| 32–33.85 | 4 (1) | 8 (3) | 14 (4) | |

| 25–31.85 | 2 (1) | 6 (2) | 15 (4) | |

|

| ||||

| Birth weight (grams; N=988) | ||||

| ≥2500 | 281 (94) | 253 (88) | 346 (86) | <0.001 |

| 1500–2499 | 16 (5) | 29 (10) | 41 (10) | |

| 1000–1499 | 1 (<1) | 3 (1) | 12 (3) | |

| <1000 | 0 | 1 (<1) | 5 (1) | |

|

| ||||

| Pregnancy complication | ||||

| No | 248 (83) | 201 (70) | 252 (61) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 52 (17) | 87 (30) | 159 (39) | |

|

| ||||

| Referral | ||||

| None mentioned | 243 (81) | 213 (74) | 276 (67) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 57 (19) | 75 (26) | 135 (33) | |

|

| ||||

| Number of lesions (N=996) | ||||

| 1 | 247 (83) | 230 (80) | 292 (71) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 34 (11) | 40 (14) | 70 (17) | |

| 3 | 8 (3) | 8 (3) | 26 (6) | |

| 4 | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 8 (2) | |

| ≥5 | 5 (2) | 6 (2) | 14 (3) | |

|

| ||||

| Complication | ||||

| No | 267 (89) | 255 (89) | 367 (89) | 0.88 |

| Yes | 33 (11) | 33 (11) | 44 (11) | |

|

| ||||

| Treatment | ||||

| No | 277 (92) | 264 (92) | 376 (91) | 0.69 |

| Yes | 23 (8) | 24 (8) | 35 (9) | |

Patient could be listed in more than one group.

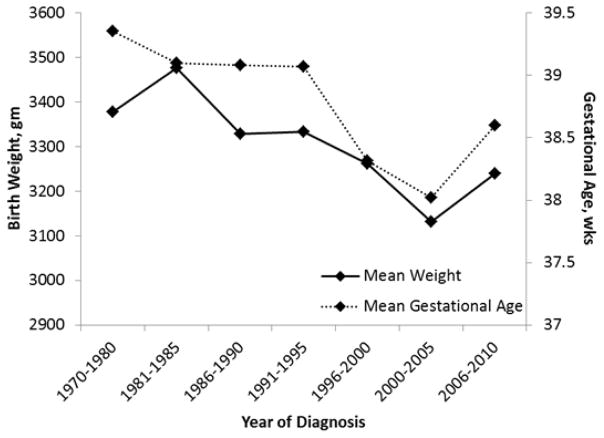

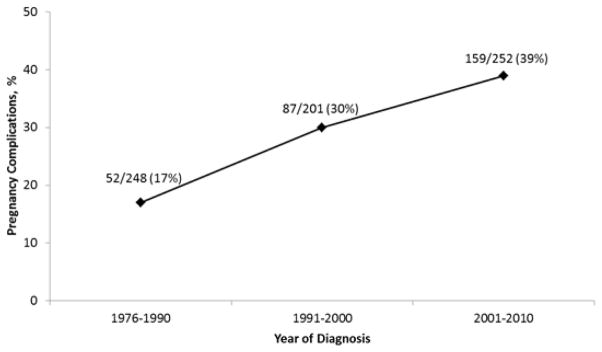

Average size of lesion did not demonstrate significant change. Average gestational age at birth and birth weight for infants diagnosed with IH decreased over the 3 decade time period (39.2 to 38.3 weeks, p<0.001 and 3383 to 3185 grams, p=0.003, respectively) (Fig 3). Maternal pregnancy complication rate increased from 17 to 39% (p<0.001) (Fig 4).

Figure 3.

Changes in Birth Weight and Gestational Age (Olmstead County, Minnesota 1976–2010).

Figure 4.

Changes in Maternal Pregnancy Complication Rate (Olmstead County, Minnesota1976–2010).

The percentage of patients referred to a subspecialist increased from 19 to 33%, with increase in dermatology referrals accounting for the majority of this change. Mean age at referral was noted to decrease from 7.8 to 5.2 months (p<0.001). Complication rate and type of complication was stable across the study period.

DISCUSSION

Accurate estimation of the incidence of IH has previously been difficult due to a lack of large, population-based studies. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a temporal trend in incidence of IH over recent decades. Incidence of IH significantly and steadily increased over the 35-year study period (Fig 2). Previous studies identified decreased gestational age at birth and decreased birth weight, as well as other maternal-fetal characteristics, as risk factors for development of IH6, 8–10. The observed increase in incidence of IH throughout our study period strongly correlated with a steady decline in gestational age at birth and in birth weight, as well as an increase in pregnancy complications. These novel and significant findings provide important insight into possible pathogenic factors of IH. Notably, the decreasing gestational age of affected infants in our study mirrors increasing prematurity rates seen in the United States over the past several decades, making our findings relevant to the general population of the United States14.

The incidence of IH over the 35-year period was 1.64 per 100 person-years, with a current incidence of 1.97 per 100 person-years, which is lower than previous estimates1, 5, 6, 15. Geographic differences in the study population may partly account for the lower estimated incidence, particularly in regard to maternal-fetal health. According to the Center for Disease Control National Vital Statistics Reports, Minnesota consistently has lower rates of preterm birth, low birth weight infants, and infant mortality compared to national averages16–18.

Prior studies may have overestimated incidence for several reasons. Lack of consistency in nomenclature may explain overestimated incidence in studies conducted before the standardization in classification of vascular birthmarks 2, 4. Referral bias has likely been a factor in studies that were conducted at referral centers, within dermatology practices, or by those with special interest/expertise2, 15. Two recent studies which found incidence rates of 4.5 and 2.6%5, 6, respectively, were cohort studies rather than population-based studies, each from a single hospital, which may have significantly impacted their accuracy. Through use of the REP, we were able to conduct a true population-based study, and thereby minimize referral bias.

The increase in referrals to subspecialists (particularly dermatologists) over the 35-year period is an interesting finding, perhaps corresponding with increased recognition of IH as potentially complicated lesions, greater availability of pediatric dermatologists, and evolution of treatment options including the discovery of beta-blockers as a treatment for IH over recent years19–23. Over the study period, infants were referred to a subspecialist at an increasingly younger age, which is encouraging, as early initiation of treatment has demonstrated improved outcomes24. A recent study found IH growth to be earlier than previously believed, with 80% of growth complete by 3 months of age25. The period of most rapid IH growth appears to be in the first 8 weeks of life, thus emphasizing need for early referral and treatment in order to minimize complications26. Although referral rates increased over time in our study, complication rates did not demonstrate change. We hypothesize that complication rates may decrease in the future with earlier and more widespread use of beta-blockers. The prevalence of various therapeutic interventions over a three decade period does not reflect current practice.

Limitations of the study include that the population of Olmsted County, Minnesota is predominantly non-Hispanic white, thus impacting our ability to report racial/ethnic differences in incidence of IH. Our estimate of IH may be low due to underreporting, as we relied on physician/provider diagnosis of IH. Some providers may have chosen not to document the presence of IH due to belief that these lesions are medically insignificant. True cases of IH may have inadvertently been excluded by the authors in the process of rigorous medical record review, contributing to the low estimate of incidence. Our review was limited to the records of infants, and documentation of the prenatal course was often brief. Therefore, maternal pregnancy complications are likely underreported in our data.

Unique strengths of this study included the ability to utilize the REP to conduct a population-based study and follow individual patient medical records over time.

Knowledge of the true incidence of IH and documentation of temporal changes to incidence, risk factors, and lesion characteristics are important steps in identifying those at highest risk, and guiding efforts aimed at discovering a precise pathogenesis underlying IH development.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES: None.

ABBREVIATIONS

- IH

infantile hemangiomas

- REP

Rochester Epidemiology Project

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE: None declared.

IRB: This study was approved by Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center IRBs. Mayo IRB#: PR12-004598-02; OMC IRB#: 034-OMC-12.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jacobs AH, Walton RG. The incidence of birthmarks in the neonate. Pediatrics. 1976;58:218–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilcline C, Frieden IJ. Infantile hemangiomas: how common are they? A systematic review of the medical literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:168–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frieden IJ, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Mancini AJ, Friedlander SF, Boon L, et al. Infantile hemangiomas: current knowledge, future directions. Proceedings of a research workshop on infantile hemangiomas, April 7–9, 2005, Bethesda, Maryland, USA Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:383–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finn MC, Glowacki J, Mulliken JB. Congenital vascular lesions: clinical application of a new classification. J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18:894–900. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickison P, Christou E, Wargon O. A prospective study of infantile hemangiomas with a focus on incidence and risk factors. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:663–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munden A, Butschek R, Tom W, Marshall JS, Poeltler DM, Krohne SE, et al. Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: Incidence, clinical characteristics, and association with placental anomalies. Br J Dermatol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bjd.12804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoornweg MJ, Smeulders MJ, Ubbink DT, van der Horst CM. The prevalence and risk factors of infantile haemangiomas: a case-control study in the Dutch population. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:156–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amir J, Metzker A, Krikler R, Reisner SH. Strawberry hemangioma in preterm infants. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:331–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemangioma Investigator G. Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, et al. Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: demographic, prenatal, and perinatal characteristics. J Pediatr. 2007;150:291–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drolet BA, Swanson EA, Frieden IJ. Infantile hemangiomas: an emerging health issue linked to an increased rate of low birth weight infants. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008;153:712–5. 5e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton BK, Schulz CJ, Angle B, Burd LI. An increased incidence of haemangiomas in infants born following chorionic villus sampling (CVS) Prenat Diagn. 1995;15:209–14. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970150302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1059–68. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs AH. Strawberry hemangiomas; the natural history of the untreated lesion. Calif Med. 1957;86:8–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJ, Wilson EC, Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61:1–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality statistics from the 2010 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML. Births: final data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2005;54:1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leaute-Labreze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, Boralevi F, Thambo JB, Taieb A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0708819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogeling M, Adams S, Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e259–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marqueling AL, Oza V, Frieden IJ, Puttgen KB. Propranolol and infantile hemangiomas four years later: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:182–91. doi: 10.1111/pde.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frieden IJ, Drolet BA. Propranolol for infantile hemangiomas: promise, peril, pathogenesis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:642–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakkittakandiyil A, Phillips R, Frieden IJ, Siegfried E, Lara-Corrales I, Lam J, et al. Timolol maleate 0.5% or 0. 1% gel-forming solution for infantile hemangiomas: a retrospective, multicenter, cohort study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:28–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sagi L, Zvulunov A, Lapidoth M, Ben Amitai D. Efficacy and safety of propranolol for the treatment of infantile hemangioma: a presentation of ninety-nine cases. Dermatology. 2014;228:136–44. doi: 10.1159/000351557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tollefson MM, Frieden IJ. Early growth of infantile hemangiomas: what parents' photographs tell us. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e314–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]