Abstract

Background and Purpose

Diverse proteases cleave protease‐activated receptor‐2 (PAR2) on primary sensory neurons and epithelial cells to evoke pain and inflammation. Trypsin and tryptase activate PAR2 by a canonical mechanism that entails cleavage within the extracellular N‐terminus revealing a tethered ligand that activates the cleaved receptor. Cathepsin‐S and elastase are biased agonists that cleave PAR2 at different sites to activate distinct signalling pathways. Although PAR2 is a therapeutic target for inflammatory and painful diseases, the divergent mechanisms of proteolytic activation complicate the development of therapeutically useful antagonists.

Experimental Approach

We investigated whether the PAR2 antagonist GB88 inhibits protease‐evoked activation of nociceptors and protease‐stimulated oedema and hyperalgesia in rodents.

Key Results

Intraplantar injection of trypsin, cathespsin‐S or elastase stimulated mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia and oedema in mice. Oral GB88 or par2 deletion inhibited the algesic and proinflammatory actions of all three proteases, but did not affect basal responses. GB88 also prevented pronociceptive and proinflammatory effects of the PAR2‐selective agonists 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 and AC264613. GB88 did not affect capsaicin‐evoked hyperalgesia or inflammation. Trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase increased [Ca2+]i in rat nociceptors, which expressed PAR2. GB88 inhibited this activation of nociceptors by all three proteases, but did not affect capsaicin‐evoked activation of nociceptors or inhibit the catalytic activity of the three proteases.

Conclusions and Implications

GB88 inhibits the capacity of canonical and biased protease agonists of PAR2 to cause nociception and inflammation.

Abbreviations

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- GB88

N‐[(2S)‐3‐cyclohexyl‐1‐[[(2S,3R)‐3‐methyl‐1‐oxo‐1‐spiro[indene‐1,4′‐piperidine]‐1′‐ylpentan‐2‐yl]amino]‐1‐oxopropan‐2‐yl]‐1,2‐oxazole‐5‐carboxamide

- PAR

protease‐activated receptor

- TRP

transient receptor potential

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| GPCRs a | Enzymes c |

| PAR2 | Cathepsin‐S |

| Voltage‐gated ion channels b | Elastase |

| TRPV1 | Trypsin |

| TRPV4 |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (a,b,cAlexander et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c).

Introduction

Serine, cysteine and metalloproteases can signal to cells by cleaving protease‐activated receptors (PARs), a family of four G‐protein coupled receptors (PAR1–4) (Ossovskaya and Bunnett, 2004; Hollenberg et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2014b). PAR2 is expressed by epithelial, endothelial and smooth muscle cells, as well as by cells of the immune and nervous systems (Nystedt et al., 1995, 1994; Bohm et al., 1996). Proteases that activate PAR2 in primary sensory neurons stimulate the release of substance P and CGRP in peripheral tissues, leading to neurogenic inflammation (Steinhoff et al., 2000). PAR2 can also sensitize and activate transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels in primary sensory neurons, including TRP vanilloid 1 and 4 (TRPV1 and TRPV4) and ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) (Amadesi et al., 2004; Dai et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2007), which results in central transmission, neuropeptide release in the spinal cord and nociceptive transmission (Vergnolle et al., 2001). Proteases that activate PAR2 on epithelial cells can promote disassembly of tight junctions (Jacob et al., 2005), induce cyclooxygenase 2 (Wang et al., 2008) and stimulate release of proinflammatory cytokines (Wang et al., 2010). PAR2 deletion ameliorates inflammatory and painful disorders of the airways, joints, colon and skin (Lindner et al., 2000; Schmidlin et al., 2002; Ferrell et al., 2003; Shichijo et al., 2006; Cottrell et al., 2007; Cattaruzza et al., 2011). These observations suggest that PAR2 is an important target for inflammatory and painful disorders. However, the development of therapeutically useful antagonists has been hampered by the unusual mechanism of PAR2 auto‐activation.

The canonical mechanism by which trypsin and mast cell tryptase activate PAR2 involves hydrolysis of Arg36↓Ser37 and exposure of the tethered ligand S37LIGKV‐ (human PAR2), which binds to and activates the cleaved receptor (Nystedt et al., 1994; Bohm et al., 1996). Synthetic peptides that mimic the tethered ligand can directly activate PAR2 and are useful tools to probe receptor function. Trypsin‐activated PAR2 couples to Gαq and phospholipase Cβ, leading to mobilization of intracellular calcium and activation of PKC and D (Amadesi et al., 2006; Amadesi et al., 2009). Trypsin‐activated PAR2 also recruits G protein receptor kinase 2 and β‐arrestins, which mediate PAR2 endocytosis and ERK1/2 signalling from endosomes (Dery et al., 1999; DeFea et al., 2000; Ayoub and Pin, 2013; Jensen et al., 2013). The development of PAR2 antagonists is complicated by this mechanism of intramolecular receptor activation by a proteolytically exposed tethered ligand. Another complication is the existence of divergent mechanisms of proteolytic activation (Hollenberg et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2014b). Proteases that cleave PAR2 distal to the canonical cleavage site can disarm the receptor by removing the trypsin‐activation site. For example, neutrophil/leukocyte elastase cleaves PAR2 at Ser67↓Val68, which removes the trypsin cleavage site and thereby blocks the capacity of trypsin to activate the receptor (Dulon et al., 2003). However, proteases that cleave PAR2 at different sites within the N‐terminal domain can create different tethered ligands or stabilize unique receptor conformations and thereby can act as biased agonists that promote PAR2 coupling to divergent signalling pathways. Cathepsin‐S, a cysteine protease secreted by antigen‐presenting cells, cleaves PAR2 at Glu56↓Thr57, to reveal a different tethered ligand that promotes PAR2 coupling to Gαs, adenylyl cyclase, cAMP and PKA, but not to Gαq and β‐arrestins (Zhao et al., 2014a). Cathepsin‐S can also cleave PAR2 at Gly41↓Lys42 (Elmariah et al., 2014). Elastase is also a biased agonist that promotes PAR2 coupling to Gαs, adenylyl cyclase, cAMP and PKA, but not to Gαq and β‐arrestins, although elastase does not activate PAR2 by a tethered ligand mechanism (Ramachandran et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2015). Despite these divergent mechanisms of PAR2 activation, both canonical and biased protease agonists cause PAR2‐ and TRPV4‐dependent inflammation and pain (Grant et al., 2007; Poole et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014a, 2015). Thus, therapeutically useful antagonists may need to disrupt the capacity of diverse proteases to activate PAR2 at different sites by canonical and biased mechanisms.

Although antibodies that target the canonical PAR2 cleavage site have efficacy in preclinical models of inflammatory disease (Kelso et al., 2006; Yau et al., 2013), it is uncertain whether they can block activation of the receptor by biased proteases that cleave at distant sites. The small molecule PAR2 antagonist ENMD‐1068 and peptidomimetic antagonists based on the canonical tethered ligand domain, including K‐14585 and C391, can also inhibit PAR2‐mediated inflammation and pain, but their ability to suppress biased mechanisms of PAR2 activation has not been reported (Kelso et al., 2006; Goh et al., 2009; Yau et al., 2013; Boitano et al., 2015). GB83 and GB88 are small molecules that can inhibit PAR2 activation by trypsin, tryptase and tethered ligand‐derived agonists and are efficacious in preclinical models of inflammatory diseases (Barry et al., 2010; Suen et al., 2012; Lohman et al., 2012a, 2012b). However, it has not yet been reported whether GB88 can antagonize the actions of canonical and biased agonists of PAR2 on nociceptor activity and nociception. We examined the effects of GB88 on the capacity of canonical and biased proteases to activate rodent nociceptors and induce pain and inflammation.

Methods

Animals

Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath & Lilley, 2015).The Animal Ethics Committee of Monash University approved procedures using animals. Male C57BL/6, par2 −/− and par2 +/+ mice littermates (Lindner et al., 2000) (8–12 weeks‐old), and male Sprague Dawley rats (7–8 weeks‐old) were studied. Animals were maintained under temperature (22 ± 4°C) and light‐controlled (12 h light/dark cycle) conditions with free access to food and water.

Mechanical hyperalgesia and oedema

Mice were placed in individual cylinders on a mesh stand. They were acclimatized to the experimental room, restraint apparatus and investigator for 2 h periods on two successive days before experiments. To assess mechanical pain, paw withdrawal in response to stimulation of the plantar surface of the hindpaw with graded von Frey filaments (0.078, 0.196, 0.392, 0.686, 1.569, 3.922, 5.882, 9.804, 13.725 and 19.608 mN) was determined using the ‘up‐and‐down’ paradigm (Chaplan et al., 1994). In this analysis, an increase in the filament stiffness required to induce paw withdrawal indicates mechanical analgesia, whereas a decrease in the filament stiffness required to induce withdrawal indicates mechanical hyperalgesia. On the day before the study, von Frey scores were measured in triplicate to establish a baseline for each animal. To assess inflammatory oedema of the paw, hind paw thickness was measured using digital callipers before and after treatments (Zhao et al., 2014a, 2015).

Thermal hyperalgesia

For studies of thermal hyperalgesia, paw withdrawal latencies to thermal stimulation of the plantar surface of the hind paw were measured in unrestrained mice using Hargreaves' apparatus (Amadesi et al., 2006). Mice were placed in plastic chambers on a glass surface (25°C) and acclimatized for 1 h before baseline readings were collected. A radiant heat source was applied to the hind paw, and latency of the paw withdrawal was taken as the average of three trials per animal. A cut‐off latency was set at 20 s to avoid tissue damage. In this analysis, an increase in latency indicates thermal analgesia, whereas a decrease in latency indicates thermal hyperalgesia.

PAR2 antagonist and agonists

Investigators were blinded to the experimental treatments. GB88 (10 mg·kg−1 in olive oil) or vehicle (control and olive oil) was administered by gavage (150 μL) 2 h before intraplantar injections. For intraplantar injections, mice were sedated with 5% isoflurane. Trypsin (140 nM, 0.04 U·μL−1), elastase (1.18 μM, 0.03 U·μL−1), cathepsin‐S (2.5 μM, 0.06 U·μL−1), 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 (64 μM, 50 ng·μL−1), AC264613 (250 μM, 100 ng·μL−1), capsaicin (1.6 μM, 0.5 ng·μL−1) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl) was injected s.c. into the plantar surface of the left hind paw (10 μL). Mechanical hyperalgesia, paw thickness and thermal hyperalgesia were measured hourly for 4 h.

In situ hybridization

cDNAs for mouse and rat PAR2 were amplified by using RNA from mouse or rat colon. The following forward and reverse primers were used: mouse PAR2, CACCGGGACGCAACAACAGTAAAG (mPar2_F199) and GAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGATATGCAGCTGTTGAGGGTCGACAG (mPar2_R1136_T7); rat PAR2, GAATGCACCGGGACCCAACAGTAA (rPAR2_F165) and GAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGATGGAGGTGAGCGATATCTGCATGC (rPAR2_R1216_T7). The design of the reverse primers included the T7 promoter sequence (underlined), which allowed the PCR products to be used directly for the generation of digoxigenin (DIG)‐labelled antisense cRNA probes by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (Roche Products, Dee Why, NSW, Australia). Sections (12 μm) of mouse and rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG, lumbar) or trigeminal ganglia were processed for combined in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence as described previously (Bron et al., 2014; Lieu et al., 2014). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti‐CGRP (Sigma #C8198; 1:2000), mouse anti‐heavy chain neurofilament (NF200, Sigma; #N0142; 1000). Biotinylated isolectin B4 (IB4) was from Sigma (#L2140). Secondary antibodies used were donkey anti‐mouse‐Alexa‐488 (1:500), donkey anti‐rabbit‐Alexa568 (1:1000) and streptavidin‐Alexa647 (1:500) (Thermofisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sections were imaged using 10× or 20× objective magnification on a Zeiss Axioskope.Z1 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberkocken, Germany). Images were processed using the Zeiss Zen software and exported as TIFF files to Adobe Photoshop for figure preparation.

Dissociation of DRG neurons

DRG were collected from Sprague Dawley rats. Neurons were dispersed as described previously with modifications (Zhao et al., 2014a; 2015). Briefly, DRG from all levels were incubated with collagenase IV (2 mg·mL−1), dispase II (2 mg·mL−1) and DNase I (100 μg·mL−1) for 40 min at 37°C. Cells were centrifuged (500 g, 5 min), re‐suspended in HBSS and filtered through a 40 μm nylon mesh. Filtered cells were centrifuged, re‐suspended in 1 mL of HBSS and layered onto a 20% Percoll gradient in Leibovitz's L‐15 medium. The gradient was centrifuged (800 g, 9 min). The supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was washed with L‐15 medium. Neurons were placed in 96 well plates coated with laminin (0.004 mg·mL−1) and poly‐l‐lysine (0.1 mg·mL−1). Neurons were cultured in L‐15 medium containing 10% FCS, with penicillin and streptomycin for 16 h at 37°C.

Measurement of [Ca2 +]i in DRG neurons

Neurons were loaded with Fura2‐AM (2 μM, 1.5 h, 37°C). Neurons were incubated in calcium buffer (150 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1.18 mM MgCl2, 10 mM D‐glucose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) at 37°C on the stage of a Leica DMI6000B microscope equipped with a PL APO × 20 NA 0.75 objective (Leica Microsystems, North Ryde, NSW, Australia). Fluorescence was measured at 340 and 380 nm excitation with 530 nm emission using an Andor iXon 887 camera (Andor Technology, Belfast, UK) and metafluor version 7.8.0 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) (Zhao et al., 2014a; Zhao et al., 2015). Neurons were challenged sequentially with trypsin (10 nM, 2.85 mU·μL−1), elastase (100 nM, 2.54 mU·μL−1) or cathepsin‐S (100 nM, 2.4 mU·μL−1), followed by capsaicin (1 μM) and KCl (50 mM). In some experiments, neurons were incubated with GB88 (10 μM) or vehicle (control) (30 min pre‐incubation and inclusion throughout). Images were analysed using a custom journal in metamorph software version 7.8.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). A maximum intensity image was generated and projected through time to generate an image of all cells. Cells were segmented and binarized from this image using the Multi Wavelength Cell Scoring module on the basis of size and fluorescence intensity. Neurons of interest (<25 μm diameter) were selected. Results are expressed as the proportion of capsaicin‐ and KCl‐responsive neurons that also responded to proteases.

Fluorogenic protease assays

GB88 (10 μM) was pre‐incubated with the appropriate fluorogenic substrate (50 μM): trypsin, H‐D‐Ala‐Leu‐Lys‐AMC; elastase, MeOSuc‐Ala‐Ala‐Pro‐Val‐AMC, cathepsin‐S: Boc‐Val‐Leu‐Lys‐AMC. Proteases were added to give final concentrations of 10 nM trypsin, 100 nM elastase or 100 nM cathepsin‐S. Substrate cleavage was assessed by measuring fluorescence during the initial 60–120 s (ex/em 360/440 nm). The slope was determined in the linear range and presented as % of the control.

Covalent activity‐based probe protease assays

Recombinant proteases (100 ng) were diluted in 20 μL PBS containing GB88 (0, 1 or 10 μM) and DMSO (1%) and were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The appropriate activity‐based probes were added: trypsin, PK‐DPP (1 μM); elastase, V‐DPP (1 μM), cathepsin‐S, BMV109 (100 nM) (Pan et al., 2006; Gilmore et al., 2009; Verdoes et al., 2013). Proteases were incubated with activity‐based probes for 5 min at 37°C, solubilized with sample buffer, boiled and separated on a 15% SDS‐PAGE gel. Probe labelling was detected by scanning gels for Cy5 fluorescence using a Typhoon FLA 7000 Scanner (GE Healthcare, Parramatta, NSW, Australia).

Statistical Analyses

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were analysed in graphpad prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) using Student's t‐test or ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. Post hoc tests were used only if F achieved P < 0.05 and there was no significant variance in homogeneity. Differences between means with a P‐value < 0.05 were considered significant at the 95% confidence level.

Materials

GB88 (N‐[(2S)‐3‐cyclohexyl‐1‐[[(2S,3R)‐3‐methyl‐1‐oxo‐1‐spiro[indene‐1,4′‐piperidine]‐1′‐ylpentan‐2‐yl]amino]‐1‐oxopropan‐2‐yl]‐1,2‐oxazole‐5‐carboxamide) was prepared as described previously (Barry et al., 2010; Suen et al., 2012). The PAR2 agonists 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 was from American Peptide Company Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and AC264613 was from Tocris Biosciences (Bristol, UK). Human pancreatic trypsin (100 000 U·mL−1) was from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Human cathepsin‐S (0.4 U·mL−1) was a gift from Medivir AB (Huddinge, Sweden) and has been described previously (Zhao et al., 2014a). Human sputum elastase (864 U·mg−1) was from Elastin Products Company (Owensville, MO, USA). Fluorogenic protease substrates were from Bachem AG (Budendorf, Switzerland): trypsin, H‐D‐Ala‐Leu‐Lys‐AMC; elastase, MeOSuc‐Ala‐Ala‐Pro‐Val‐AMC; cathepsin‐S, Bock‐Val‐Leu‐Lys‐AMC. The activity‐based protease probes Cy5‐ProLys‐diphenyl phosphonate (PK‐DPP), Cy5‐Val‐diphenyl phosphonate (V‐DPP) and BMV109 were synthesized as described previously (Pan et al., 2006; Gilmore et al., 2009; Verdoes et al., 2013). Unless otherwise indicated, other reagents were from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Results

GB88 antagonized the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of canonical and biased protease agonists of PAR2

Proteases that cleave PAR2 at different sites within the extracellular N‐terminal domain can activate canonical or biased signalling pathways (Hollenberg et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2014b). Although PAR2 deletion attenuates the pronociceptive and proinflammatory actions of trypsin, tryptase, elastase and cathepsin‐S (Vergnolle et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2014a; Zhao et al., 2015), a pharmacological inhibitor of pain and inflammation induced by biased protease agonists of PAR2 has not been identified. We evaluated whether GB88 inhibits trypsin‐, elastase‐ and cathepsin‐S‐evoked inflammation and nociception in mice.

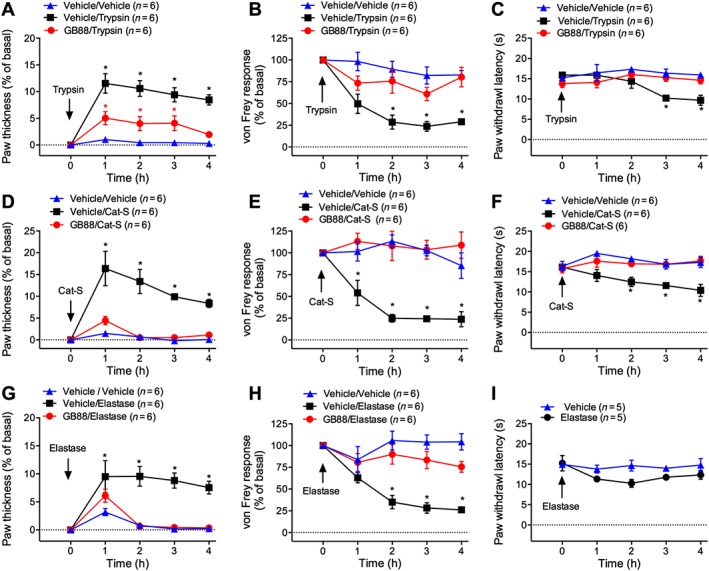

Intraplantar injection of trypsin stimulated a 12% increase in paw thickness within 1 h that was sustained for 4 h, indicative of oedema (Figure 1A). Trypsin caused a significant reduction in von Frey responses between 2–4 h, consistent with mechanical hyperalgesia (Figure 1B), and decreased the latency of paw withdrawal to heat from 3 to 4 h, indicating thermal hyperalgesia (Figure 1C). P.o. administration of GB88 (10 mg·kg−1) 2 h before injection of trypsin reduced the effects of trypsin on paw thickness by ~50% and prevented trypsin‐induced mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia (Figure 1A–C).

Figure 1.

Effects of GB88 on protease‐evoked inflammation and nociception. Mice were treated with GB88 (10 mg·kg−1 p.o.) or vehicle 2 h before intraplantar injections of trypsin (A–C; 30 ng), cathepsin‐S (Cat‐S, D–F; 14 μg), elastase (G–I; 290 ng) or vehicle. Paw thickness (A, D and G), paw withdrawal to mechanical stimulation (B, E and H) and paw withdrawal to thermal stimulation (C, F and I) were measured. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle/vehicle control. Variable n indicates mouse number.

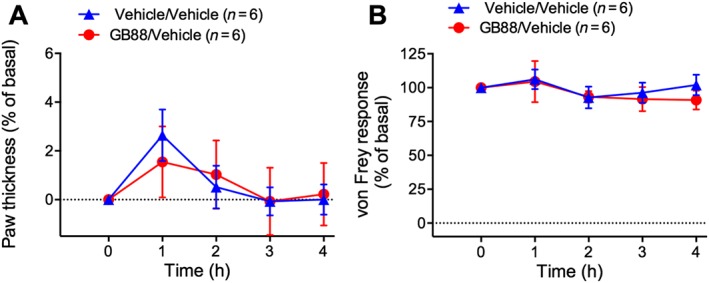

Intraplantar injection of cathepsin‐S caused a 16% increase in paw thickness within 1 h, which was sustained for 4 h (Figure 1D). Cathepsin‐S reduced the von Frey response from 1 to 4 h (Figure 1E) and decreased latency time to paw withdrawal from heat at 2–4 h (Figure 1F). GB88 abolished cathepsin‐S‐induced oedema and attenuated cathepsin‐S‐stimulated mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia (Figure 1D–F). Intraplantar injection of elastase caused a 9% increase in paw thickness at 1 h that was sustained for 4 h (Figure 1G). Elastase reduced the von Frey response from 2 to 3 h, consistent with mechanical hyperalgesia (Figure 1H). In contrast to trypsin and cathepsin‐S, elastase did not cause significant thermal hyperalgesia (Figure 1I). GB88 attenuated elastase‐induced oedema and mechanical hyperalgesia (Figure 1G–I). Intraplantar injection of vehicle did not induce oedema or mechanical hypersensitivity, and GB88 did not affect baseline paw thickness (Figure 2A) or mechanical sensitivity (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effects of GB88 on basal inflammation and nociception. Mice were treated with GB88 (10 mg·kg−1 p.o.) or vehicle 2 h before intraplantar injection of vehicle. Paw thickness (A) and paw withdrawal to mechanical stimulation (B) were measured hourly for 4 h. Variable n indicates mouse number.

Thus, GB88 inhibits the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of proteases that activate PAR2 by canonical and biased mechanisms.

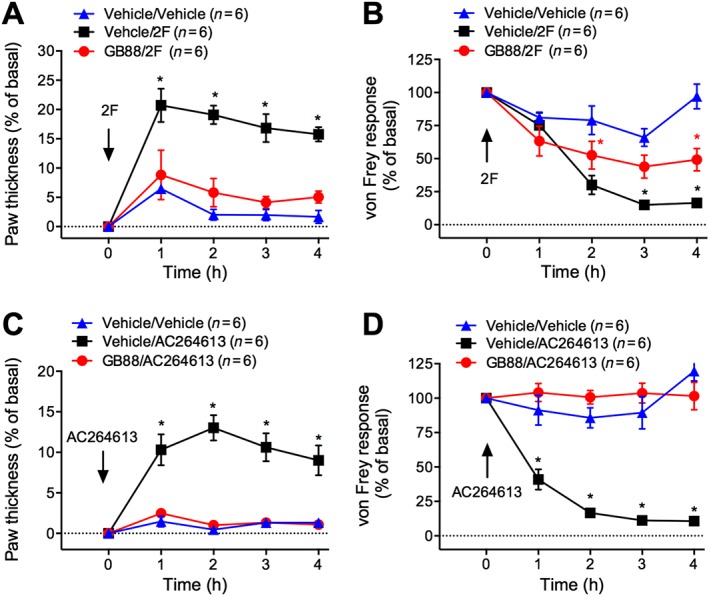

GB88 antagonized the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of synthetic PAR2 agonists

Synthetic peptides that mimic the trypsin‐exposed tethered ligand can directly activate PAR2. Like trypsin, these activating peptides induce PAR2 coupling to Gαq and β‐arrestins, sensitize TRP channels, and cause inflammation and pain (Amadesi et al., 2004; Dai et al., 2004; Grant et al., 2007). We investigated whether GB88 inhibited the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2, an analogue of the tethered ligand domain (Kanke et al., 2005), and AC264613, a small molecule agonist of PAR2 that elicits thermal hyperalgesia and oedema (Gardell et al., 2008).

Intraplantar injection of 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 caused a 21% increase in paw thickness at 1 h, which was sustained for 4 h (Figure 3A). 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 reduced the von Frey withdrawal response from 2 to 4 h, indicative of mechanical hyperalgesia (Figure 3B). GB88 inhibited oedema induced by 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 and reduced mechanical hyperalgesia by 30% (Figure 3A, B). Intraplantar injection of AC264613 induced a 10% increase in paw thickness at 1 h that persisted for 4 h (Figure 3C). AC264613 also evoked a robust mechanical hyperalgesia from 1 to 4 h (Figure 3D). GB88 prevented the proinflammatory and pronociceptive effects of AC264613 (Figure 3C, D). Thus, GB88 inhibits mouse paw inflammation and nociception caused by small molecule synthetic agonists of PAR2.

Figure 3.

Effects of GB88 on PAR2 agonist‐evoked inflammation and nociception. Mice were treated with GB88 (10 mg·kg−1 p.o.) or vehicle 2 h before intraplantar injections of 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 (2F) (A and B; 500 ng) or AC264613 (C and D; 1 μg). Paw thickness (A and C) and paw withdrawal to mechanical stimulation (B and D) were measured hourly for 4 h. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle/vehicle control. Variable n indicates mouse number.

GB88 did not affect the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of capsaicin

The capacity of GB88 to inhibit protease‐ and PAR2‐evoked inflammation and nociception could be due to antagonism of PAR2 or downstream mediators, such as TRP channels. TRPV1 is a downstream target of PAR2 that contributes to the effects of proteases on inflammation and nociception (Amadesi et al., 2004). Capsaicin directly activates TRPV1 on primary sensory neurons to cause neurogenic inflammation and nociception (Caterina et al., 1997). We examined whether GB88 affected capsaicin‐induced inflammation and nociception.

Intraplantar injection of capsaicin evoked a 55% increase in paw thickness within 1 h that persisted for 4 h (Figure 4A). Capsaicin also induced a robust mechanical hyperalgesia at 1 h that was sustained for 4 h (Figure 4B). GB88 had no effect on capsaicin‐stimulated oedema and mechanical hyperalgesia (Figure 4A, B). Thus, the anti‐inflammatory and analgesic actions of GB88 are not due to antagonism of TRPV1, because the proinflammatory and nociceptive effects of capsaicin were unaffected.

Figure 4.

Effects of GB88 on capsaicin‐evoked inflammation and nociception. Mice were treated with GB88 (10 mg·kg−1 p.o.) or vehicle 2 h before intraplantar injection of capsaicin (Cap, 5 μg). Paw thickness (A) and paw withdrawal to mechanical stimulation (B) were measured hourly for 4 h. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle/Cat‐S control. Variable n indicates mouse number.

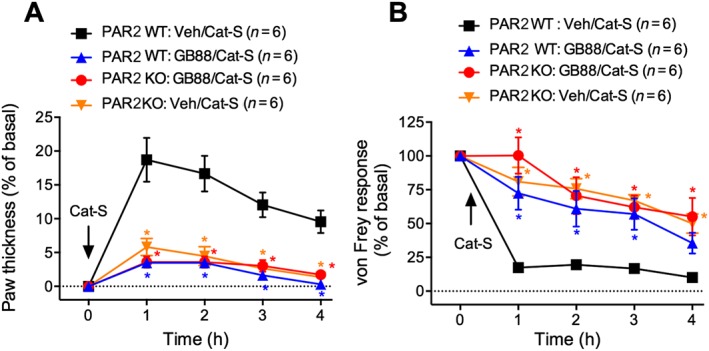

The effects of GB88 on inflammation and nociception required expression of PAR2

Deletion of par 2 attenuates the capacity of trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase to induce oedema and hyperalgesia (Vergnolle et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2014a; Zhao et al., 2015). Because par 2 deletion does not completely inhibit cathepsin‐S‐induced inflammation and nociception (Zhao et al., 2014a), we examined whether GB88 had residual actions in par 2 −/− mice, consistent with PAR2‐independent effects. In wild‐type mice, cathepsin‐S evoked a 19% increase in paw thickness (Figure 5A) and a sustained mechanical hyperalgesia (Figure 5B). GB88 inhibited cathepsin‐S‐induced oedema and hyperalgesia. Par 2 deletion also inhibited cathepsin‐S‐induced oedema and hyperalgesia, and GB88 had no additional inhibitory actions in par 2 −/− mice. The inability of GB88 to exert additional anti‐inflammatory and antinociceptive effects in par 2 −/− mice suggests that the actions of GB88 are mediated by antagonism of PAR2.

Figure 5.

Effects of GB88 on inflammation and nociception in PAR2 deficient mice. Par2 +/+ (wild‐type, WT) or par2 −/− (knockout, KO) mice were treated with GB88 (10 mg·kg−1 p.o.) or vehicle 2 h before intraplantar injection of Cat‐S (14 μg). Paw thickness (A) and paw withdrawal to mechanical stimulation (B) were measured hourly for 4 h. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle/vehicle control. Variable n indicates mouse number.

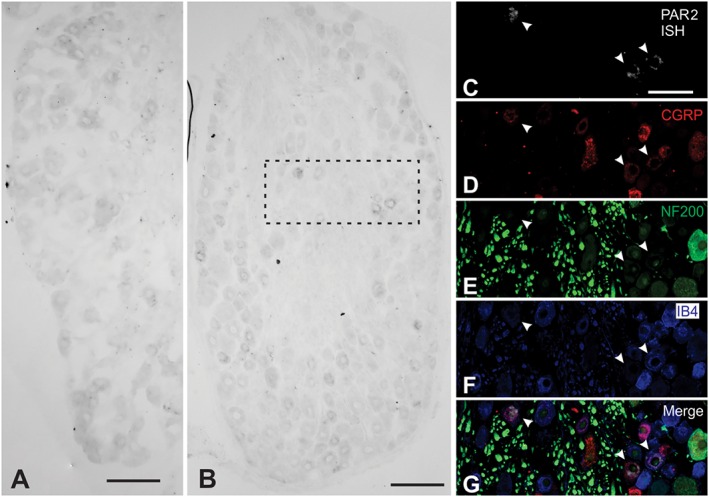

PAR2 was highly expressed by rat nociceptors

Proteases can induce neurogenic inflammation and nociception directly by activating PAR2 on primary sensory neurons (Steinhoff et al., 2000) or indirectly by releasing stimulants from keratinocytes, which express high levels of PAR2 (Steinhoff et al., 1999). We used in situ hybridization to examine the expression of PAR2 mRNA by primary sensory neurons in dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia of rat and mouse. In mice, PAR2 was detected at low levels in DRG neurons (data not shown), but was more prominently expressed in trigeminal neurons (Figure 6A). In rats, PAR2 mRNA was readily detected in DRG neurons (Figure 6B, C). PAR2‐positive neurons were of small diameter and included peptidergic neurons expressing immunoreactive CGRP and non‐peptidergic neurons that bound IB4 (Figure 6C–G). PAR2‐positive neurons did not express NF200, a marker for large diameter neurons. Thus, PAR2 mRNA is abundantly expressed in rat nociceptors.

Figure 6.

Localization of PAR2 mRNA in DRG. In situ hybridization on sections of mouse trigeminal ganglia (A) or rat DRG (B). (C–G) The inset shows an inverted image of PAR2 in situ hybridization (ISH; C), immunoreactive CGRP (D), immunoreactive neurofilament 200 (NF200; E), IB4 (F) and a merged image (G). Arrowheads show expression of PAR2 in small diameter neurons that expressed CGRP or bound IB4. Scale is 20 μm.

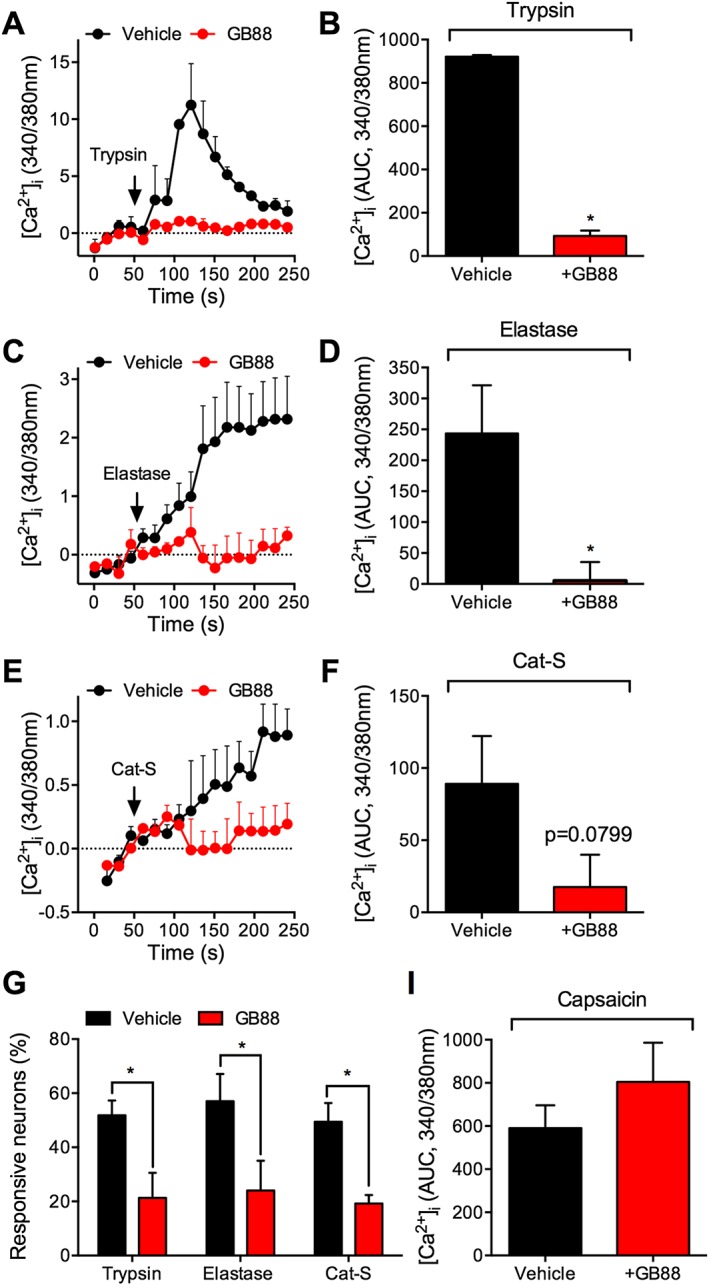

GB88 antagonized activation of nociceptors by canonical and biased protease agonists of PAR2

To determine whether GB88 can attenuate nociceptor activation by proteases that are canonical and biased agonists of PAR2, we examined protease‐induced Ca2 + signalling in DRG neurons. We studied neurons from rats, rather than mice, due to the higher expression of PAR2 mRNA in rat nociceptors (Figure 6) and because PAR2 agonists generated larger signals in a higher proportion of DRG neurons from rats than mice (not shown). We have previously reported that canonical (trypsin, tryptase) and biased (cathepsin‐S, elastase) proteolytic activators can induce PAR2‐dependent Ca2 + signals in DRG neurons (Steinhoff et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2014a; 2015). Whereas canonical proteases evoke PAR2 coupling to Gαq, and mobilization of intracellular Ca2 +, cathepsin‐S‐ and elastase‐activated PAR2 does not couple to Gαq, and instead causes Gαs‐, adenylyl cyclase‐ and PKA‐mediated activation of TRPV4, which permits influx of Ca2 + ions from the extracellular fluid (Zhao et al., 2014a, 2015).

Trypsin induced a rapid but transient increase in [Ca2 +]i that was maximal at 2 min and returned to baseline after 5 min, consistent with mobilization of Ca2 + ions from intracellular stores (Figure 7A). Cathepsin‐S and elastase caused a gradual and sustained increase in [Ca2 +]i that was maintained for at least 5 min, consistent with activation of TRPV4 and influx of extracellular Ca2 + ions (Figure 7C, F). GB88 markedly inhibited the magnitude of responses to trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase. Of all the capsaicin‐ and KCl‐responsive neurons, 52 ± 5% responded to trypsin, 49 ± 7% responded to cathepsin‐S and 57 ± 10% responded to elastase. GB88 reduced the proportion of responsive neurons by >60% (Figure 7G). In contrast, GB88 neither affected the magnitude of the Ca2 + response to capsaicin nor the proportion of capsaicin‐responsive neurons, consistent with its inability to inhibit capsaicin‐evoked inflammation and nociception. The results suggest that GB88 inhibits proteolytic activation of nociceptive neurons, which has been shown to depend in a large part on PAR2 (Zhao et al., 2014a, 2015).

Figure 7.

Effects of GB88 on protease‐induced Ca2 + signalling in DRG neurons. Rat DRG neurons were challenged with trypsin (A and B; 10 nM), elastase (C and D; 100 nM) or Cat‐S (E and F; 100 nM) in the presence of GB88 (10 μM) or vehicle (control). (A, C and E) Representative traces of kinetics of Ca2 + responses. (B, D and F) AUC from 50 to 250 s. (G) Effects of GB88 on the proportion of protease‐responsive neurons that also responded to capsaicin. *P < 0.05; n = 4–6 rats, >100 neurons analysed from each rat.

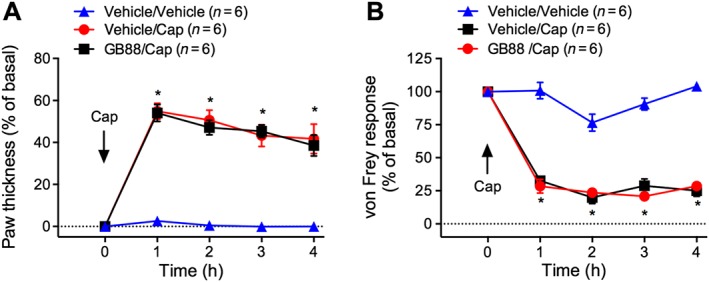

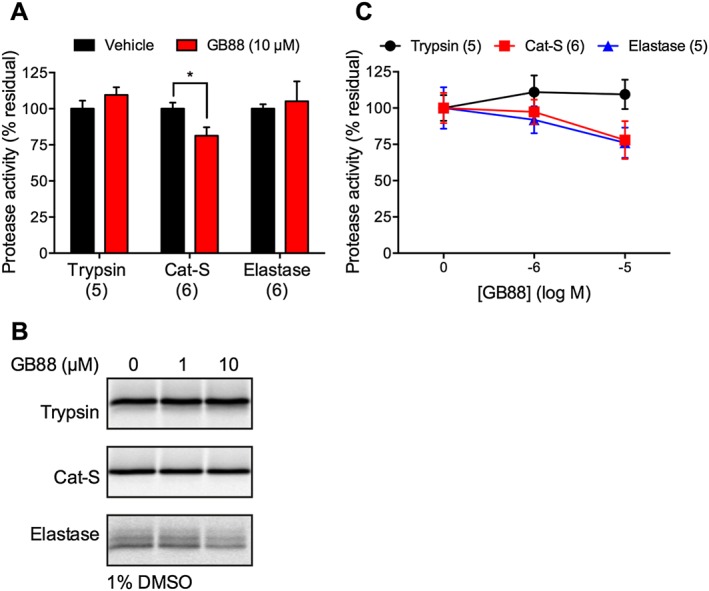

GB88 did not inhibit protease activity

To eliminate the possibility that the anti‐inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of GB88 were mediated by protease inhibition rather than PAR2 antagonism, we studied the ability of GB88 to prevent proteolytic activity. Using fluorogenic substrates, we monitored the activity of recombinant proteases upon initial interaction with GB88, mimicking the conditions that were used in the studies of DRG neurons. GB88 (1 or 10 μM) did not affect the activity of trypsin, elastase of cathepsin‐S (Figure 8A). We also tested the ability of GB88 to inhibit the covalent binding of proteases to activity‐based probes. In this assay, GB88 was incubated with the enzyme for 30 min. Trypsin activity was not affected at any concentration of GB88 tested (1, 10 μM) (Figure 8B, C). Cathepsin‐S and elastase activities were modestly affected at 10 μM (<25% inhibition). Hence, GB88 can directly inhibit proteases activity, but only at high concentrations that are unlikely to be achieved in vivo. Thus, the effects of GB88 on nociceptor activation, inflammation and nociception are unlikely to be due to direct effects on protease activity, but rather through antagonism of PAR2.

Figure 8.

Effects of GB88 on protease activity. (A) Effects of GB88 on protease cleavage of fluorogenic substrates. GB88 (10 μM) was mixed with substrates (50 μM). Proteases were added (final concentrations: trypsin, 10 nM; Cat‐S, 100 nM; elastase, 100 nM), and fluorescence was monitored. The slope of the reaction was measured during the initial 60–120 s (in the linear range). (B and C) Effects of GB88 on protease labelling by fluorescent activity‐based probes. Recombinant proteases were pretreated with GB88 (1, 10 μM) in 1% DMSO. Residual activity was determined by labelling with activity‐based probes and analysis by fluorescent SDS‐PAGE. (B) A representative gel; (C) shows quantified signals. *P < 0.05, n = 5 or 6 separate experiments.

Discussion and conclusions

GB88 antagonism of inflammation and nociception

GB88 inhibited the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of proteases that are either canonical or biased agonists of PAR2. Trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase exert proinflammatory and pronociceptive effects that are attenuated by par2 deletion (Vergnolle et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2014a; Zhao et al., 2015). However, these proteases all cleave PAR2 at different sites and induce receptor coupling to distinct G proteins and signalling pathways. Trypsin causes PKC‐ and PKA‐dependent sensitization of TRP channels and nociceptors, whereas cathepsin‐S and elastase activate TRP channels and nociceptors solely via PKA (Amadesi et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2014a; Zhao et al., 2015). Despite these differences, we found that GB88 inhibited the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase, consistent with the observation that Par 2 deletion inhibits trypsin‐, cathepsin‐S‐ and elastase‐induced inflammation and nociception (Vergnolle et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2014a; Zhao et al., 2015). GB88 did not affect capsaicin‐evoked and TRPV1‐mediated inflammation and nociception and had no additional anti‐inflammatory or antinociceptive actions in par2‐deficient mice, consistent with PAR2 being the primary target of GB88 in vivo.

GB88 inhibited the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of the synthetic PAR2 agonists 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 and AC264613. 2‐furoyl‐LIGRLO‐NH2 and AC264613 are selective for PAR2 over other PARs and induce oedema and hyperalgesia after intraplantar injection to mice (Kanke et al., 2005; Gardell et al., 2008; Suen et al., 2012). These results are consistent with GB88 inhibiting protease‐induced inflammation and pain and support the view that GB88 exerts anti‐inflammatory and analgesic actions by antagonism of PAR2.

Trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase each caused a sustained paw oedema and mechanical hyperalgesia in mice. Trypsin and cathepsin‐S, but not elastase, also caused thermal hyperalgesia. The reason for the differences in the tendency of proteases to cause thermal hyperalgesia is unknown, but may relate to the activation of different signalling processes that differentially sensitize thermo‐sensitive TRP channels. Although trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase induced PAR2‐dependent activation of TRPV4 (Zhao et al., 2014a; Zhao et al., 2015), trypsin can also sensitize TRPV1 and TRPA1 (Amadesi et al., 2004; Dai et al., 2007). Further studies are required to ascertain whether cathepsin‐S and elastase can sensitize TRPV1 and TRPA1.

GB88 antagonism of nociceptors

GB88 blocked the capacity of trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase to activate nociceptors. DRG neurons expressing PAR2 mRNA were of small diameter and included peptidergic and non‐peptidergic neurons with the characteristics of nociceptors. Our findings support other reports of prominent expression of PARs by nociceptors (Steinhoff et al., 2000; Vellani et al., 2010). Consistent with these findings, trypsin, cathepsin‐S and elastase induced robust increases in [Ca2 +]i in a substantial proportion of small diameter, capsaicin‐sensitive rat DRG neurons. Whereas trypsin stimulated a rapid and transient increase in [Ca2 +]i, consistent with mobilization of intracellular calcium stores, cathepsin‐S and elastase induced a gradual and sustained increase in [Ca2 +]i, which suggests activation of a plasma membrane channel and influx of extracellular Ca2 + ions. Regardless of the mechanism, GB88 inhibited the magnitude of protease‐evoked signals and the proportion of neurons with detectable responses. Thus, PAR2 is a prominent mediator of protease signalling to nociceptive neurons. Residual responses in GB88‐treated neurons may be attributed to activation of other receptors or channels. Elastase can also activate PAR1, and cathepsin‐S activates MrgprC11, which are expressed in nociceptors (Vellani et al., 2010; Mihara et al., 2013; Reddy et al., 2015).

GB88 mechanism and selectivity

GB88 can antagonize mouse, rat and human PAR2, consistent with the high degree of PAR2 homology in these species (Ossovskaya and Bunnett, 2004). We observed that GB88 antagonizes mouse and rat PAR2, in agreement with reports that GB88 inhibits protease‐ and PAR2‐mediated inflammation in rats (Barry et al., 2010; Suen et al., 2012; Lohman et al., 2012a, 2012b). GB88 also inhibits the effects of trypsin and synthetic PAR2 agonists on Ca2 + signalling in multiple human cell lines (Suen et al., 2012; Lohman et al., 2012a).

The molecular mechanism by which GB88 antagonizes PAR2 is not fully understood. GB88 is a competitive antagonist of SLIGRL‐NH2 and 2fLIGRLO‐NH2, surmountable and PAR2‐selective (Suen et al., 2012), displaying antagonism of Gαq signalling but activation of other G‐protein coupled signalling pathways (Suen et al., 2014). However, it has not been reported yet whether GB88 binds at the same (orthosteric) site as the tethered ligand. We found that GB88 antagonizes the activation of PAR2 by multiple proteases and synthetic agonists. Trypsin and cathepsin‐S cleave PAR2 at different sites to reveal distinctly different tethered ligands, whereas elastase activates PAR2 by a non‐tethered ligand mechanism (Zhao et al., 2014a, 2015). Although the trypsin‐exposed tethered ligand interacts with the second extracellular loop of PAR2 (Ossovskaya and Bunnett, 2004), the binding site of the cathepsin‐S‐revealed tethered ligand is unknown. Thus, GB88 likely antagonizes PAR2 by stabilizing an inactive conformation because it does not inhibit cleavage nor binding of a specific tethered ligand, rather it inhibits activation by multiple proteases, multiple peptide agonists and also nonpeptide agonists. Further studies are required to define the mechanisms by which GB88 specifically inhibits cathepsin‐S and elastase activation of PAR2.

TRP channels are downstream targets of PAR2. PAR2 can sensitize TRPV1, and TRPV1 deletion or antagonism inhibits PAR2‐dependent hyperalgesia (Amadesi et al., 2004). We found that GB88 did not affect capsaicin‐evoked calcium signals in nociceptors, consistent with its inability to inhibit the proinflammatory and hyperalgesic actions of capsaicin. These findings support the conclusion that GB88 prevents protease activation of nociceptors, inflammation and pain by antagonism of PAR2 rather than TRPV1.

To confirm that the effects of GB88 were not due to protease inhibition, we examined whether GB88 inhibits protease activity. By using a fluorogenic assay to mimic conditions of protease signalling to nociceptors in culture, we found that GB88 (10 μM) did not affect trypsin or elastase activity and had a modest effect on cathepsin‐S activity. When pre‐incubated with activity‐based probes, GB88 did not affect trypsin, cathepsin‐S or elastase binding. Thus, the effects of GB88 on inflammation and pain are more likely due to antagonism of PAR2 rather than inhibition of protease activity.

Multiple proteases become activated during injury and inflammation. The activity of these proteases is regulated by a large number of endogenous protease inhibitors. Thus, the balance between protease activation and inhibition is likely to be of crucial importance for the control of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. For example, cathepsin‐S is activated in macrophages and spinal microglial cells during colitis and in neuropathic pain states (Clark et al., 2007; Cattaruzza et al., 2011), and mast cell tryptase is elevated in patients with visceral pain (Barbara et al., 2004). Elastase released from leukocytes within sensory ganglia can contribute to neuropathic pain, which is exacerbated by deficiency in the elastase inhibitor serpinA3N (Vicuna et al., 2015). Thus, the finding that GB88 inhibits the pronociceptive actions of diverse proteases suggests a potential to suppress different forms of inflammatory and neuropathic pain that are associated with the differential activation of proteases. The findings reported here support the usefulness of GB88 and potentially other PAR2 antagonists to inhibit inflammatory and painful conditions.

Author contributions

T.M.L. and E.S. analysed nociception and inflammation. P.Z. and D.P.P. studied nociceptor activation. R.B. localized receptors by in situ hybridization. L.E.M. and N.B. analysed the enzymatic activity. P.M., R.L. and D.F. provided GB88 and conceived the studies of nociception. N.W.B. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council Centres of Excellence in Convergent Bio‐Nano Science and Technology and in Advanced Molecular Imaging. Work in NWB's laboratory is funded in part by Takeda Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Lieu, T. , Savage, E. , Zhao, P. , Edgington‐Mitchell, L. , Barlow, N. , Bron, R. , Poole, D. P. , McLean, P. , Lohman, R. ‐J. , Fairlie, D. P. , and Bunnett, N. W. (2016) Antagonism of the proinflammatory and pronociceptive actions of canonical and biased agonists of protease‐activated receptor‐2. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 2752–2765. doi: 10.1111/bph.13554.

References

- Alexander SPH, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5744–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Catterall WA, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Voltage‐gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5904–5941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015c). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadesi S, Cottrell GS, Divino L, Chapman K, Grady EF, Bautista F et al. (2006). Protease‐activated receptor 2 sensitizes TRPV1 by protein kinase Cepsilon‐ and A‐dependent mechanisms in rats and mice. J Physiol 575: 555–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadesi S, Grant AD, Cottrell GS, Vaksman N, Poole DP, Rozengurt E et al. (2009). Protein kinase D isoforms are expressed in rat and mouse primary sensory neurons and are activated by agonists of protease‐activated receptor 2. J Comp Neurol 516: 141–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadesi S, Nie J, Vergnolle N, Cottrell GS, Grady EF, Trevisani M et al. (2004). Protease‐activated receptor 2 sensitizes the capsaicin receptor transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1 to induce hyperalgesia. J Neurosci 24: 4300–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub MA, Pin JP (2013). Interaction of protease‐activated receptor 2 with g proteins and beta‐arrestin 1 studied by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Front Endocrinol 4: 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara G, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R, Cremon C, Cottrell GS, Santini D et al. (2004). Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 126: 693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry GD, Suen JY, Le GT, Cotterell A, Reid RC, Fairlie DP (2010). Novel agonists and antagonists for human protease activated receptor 2. J Med Chem 53: 7428–7440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm SK, Kong W, Bromme D, Smeekens SP, Anderson DC, Connolly A et al. (1996). Molecular cloning, expression and potential functions of the human proteinase‐activated receptor‐2. Biochem J 314 (Pt 3): 1009–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitano S, Hoffman J, Flynn AN, Asiedu MN, Tillu DV, Zhang Z et al. (2015). The novel PAR2 ligand C391 blocks multiple PAR2 signalling pathways in vitro and in vivo. Br J Pharmacol 172: 4535–4545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bron R, Wood RJ, Brock JA, Ivanusic JJ (2014). Piezo2 expression in corneal afferent neurons. J Comp Neurol 522: 2967–2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D (1997). The capsaicin receptor: a heat‐activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389: 816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaruzza F, Lyo V, Jones E, Pham D, Hawkins J, Kirkwood K et al. (2011). Cathepsin S is activated during colitis and causes visceral hyperalgesia by a PAR2‐dependent mechanism in mice. Gastroenterology 141: 1864–1874 .e1861‐1863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL (1994). Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods 53: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AK, Yip PK, Grist J, Gentry C, Staniland AA, Marchand F et al. (2007). Inhibition of spinal microglial cathepsin S for the reversal of neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 10655–10660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell GS, Amadesi S, Pikios S, Camerer E, Willardsen JA, Murphy BR et al. (2007). Protease‐activated receptor 2, dipeptidyl peptidase I, and proteases mediate Clostridium difficile toxin A enteritis. Gastroenterology 132: 2422–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SP, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Moriyama T, Higashi T, Togashi K, Kobayashi K, Yamanaka H et al. (2004). Proteinase‐activated receptor 2‐mediated potentiation of transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 activity reveals a mechanism for proteinase‐induced inflammatory pain. J Neurosci 24: 4293–4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Wang S, Tominaga M, Yamamoto S, Fukuoka T, Higashi T et al. (2007). Sensitization of TRPA1 by PAR2 contributes to the sensation of inflammatory pain. J Clin Invest 117: 1979–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFea KA, Zalevsky J, Thoma MS, Dery O, Mullins RD, Bunnett NW (2000). beta‐arrestin‐dependent endocytosis of proteinase‐activated receptor 2 is required for intracellular targeting of activated ERK1/2. J Cell Biol 148: 1267–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dery O, Thoma MS, Wong H, Grady EF, Bunnett NW (1999). Trafficking of proteinase‐activated receptor‐2 and beta‐arrestin‐1 tagged with green fluorescent protein. beta‐Arrestin‐dependent endocytosis of a proteinase receptor. J Biol Chem 274: 18524–18535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulon S, Cande C, Bunnett NW, Hollenberg MD, Chignard M, Pidard D (2003). Proteinase‐activated receptor‐2 and human lung epithelial cells: disarming by neutrophil serine proteinases. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 28: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmariah SB, Reddy VB, Lerner EA (2014). Cathepsin S signals via PAR2 and generates a novel tethered ligand receptor agonist. PLoS One 9: e99702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell WR, Lockhart JC, Kelso EB, Dunning L, Plevin R, Meek SE et al. (2003). Essential role for proteinase‐activated receptor‐2 in arthritis. J Clin Invest 111: 35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardell LR, Ma JN, Seitzberg JG, Knapp AE, Schiffer HH, Tabatabaei A et al. (2008). Identification and characterization of novel small‐molecule protease‐activated receptor 2 agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 327: 799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore BF, Quinn DJ, Duff T, Cathcart GR, Scott CJ, Walker B (2009). Expedited solid‐phase synthesis of fluorescently labeled and biotinylated aminoalkane diphenyl phosphonate affinity probes for chymotrypsin‐ and elastase‐like serine proteases. Bioconjug Chem 20: 2098–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh FG, Ng PY, Nilsson M, Kanke T, Plevin R (2009). Dual effect of the novel peptide antagonist K‐14585 on proteinase‐activated receptor‐2‐mediated signalling. Br J Pharmacol 158: 1695–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AD, Cottrell GS, Amadesi S, Trevisani M, Nicoletti P, Materazzi S et al. (2007). Protease‐activated receptor 2 sensitizes the transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 ion channel to cause mechanical hyperalgesia in mice. J Physiol 578: 715–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg MD, Mihara K, Polley D, Suen JY, Han A, Fairlie DP et al. (2014). Biased signalling and proteinase‐activated receptors (PARs): targeting inflammatory disease. Br J Pharmacol 171: 1180–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob C, Yang PC, Darmoul D, Amadesi S, Saito T, Cottrell GS et al. (2005). Mast cell tryptase controls paracellular permeability of the intestine. Role of protease‐activated receptor 2 and beta‐arrestins. J Biol Chem 280: 31936–31948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen DD, Godfrey CB, Niklas C, Canals M, Kocan M, Poole DP et al. (2013). The bile acid receptor TGR5 does not interact with beta‐arrestins or traffic to endosomes but transmits sustained signals from plasma membrane rafts. J Biol Chem 288: 22942–22960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanke T, Ishiwata H, Kabeya M, Saka M, Doi T, Hattori Y et al. (2005). Binding of a highly potent protease‐activated receptor‐2 (PAR2) activating peptide, [3H]2‐furoyl‐LIGRL‐NH2, to human PAR2. Br J Pharmacol 145: 255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso EB, Lockhart JC, Hembrough T, Dunning L, Plevin R, Hollenberg MD et al. (2006). Therapeutic promise of proteinase‐activated receptor‐2 antagonism in joint inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 316: 1017–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu T, Jayaweera G, Zhao P, Poole DP, Jensen D, Grace M et al. (2014). The bile acid receptor TGR5 activates the TRPA1 channel to induce itch in mice. Gastroenterology 147: 1417–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner JR, Kahn ML, Coughlin SR, Sambrano GR, Schauble E, Bernstein D et al. (2000). Delayed onset of inflammation in protease‐activated receptor‐2‐deficient mice. J Immunol 165: 6504–6510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman RJ, Cotterell AJ, Barry GD, Liu L, Suen JY, Vesey DA et al. (2012a). An antagonist of human protease activated receptor‐2 attenuates PAR2 signaling, macrophage activation, mast cell degranulation, and collagen‐induced arthritis in rats. FASEB J 26: 2877–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman RJ, Cotterell AJ, Suen J, Liu L, Do AT, Vesey DA et al. (2012b). Antagonism of protease‐activated receptor 2 protects against experimental colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 340: 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara K, Ramachandran R, Renaux B, Saifeddine M, Hollenberg MD (2013). Neutrophil elastase and proteinase‐3 trigger G protein‐biased signaling through proteinase‐activated receptor‐1 (PAR1). J Biol Chem 288: 32979–32990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt S, Emilsson K, Larsson AK, Strombeck B, Sundelin J (1995). Molecular cloning and functional expression of the gene encoding the human proteinase‐activated receptor 2. Eur J Biochem 232: 84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt S, Emilsson K, Wahlestedt C, Sundelin J (1994). Molecular cloning of a potential proteinase activated receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 9208–9212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossovskaya VS, Bunnett NW (2004). Protease‐activated receptors: contribution to physiology and disease. Physiol Rev 84: 579–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Jeffery DA, Chehade K, Beltman J, Clark JM, Grothaus P et al. (2006). Development of activity‐based probes for trypsin‐family serine proteases. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 16: 2882–2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole DP, Amadesi S, Veldhuis NA, Abogadie FC, Lieu T, Darby W et al. (2013). Protease‐activated receptor 2 (PAR2) protein and transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) protein coupling is required for sustained inflammatory signaling. J Biol Chem 288: 5790–5802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Mihara K, Chung H, Renaux B, Lau CS, Muruve DA et al. (2011). Neutrophil elastase acts as a biased agonist for proteinase‐activated receptor‐2 (PAR2). J Biol Chem 286: 24638–24648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VB, Sun S, Azimi E, Elmariah SB, Dong X, Lerner EA (2015). Redefining the concept of protease‐activated receptors: cathepsin S evokes itch via activation of Mrgprs. Nat Commun 6: 7864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidlin F, Amadesi S, Dabbagh K, Lewis DE, Knott P, Bunnett NW et al. (2002). Protease‐activated receptor 2 mediates eosinophil infiltration and hyperreactivity in allergic inflammation of the airway. J Immunol 169: 5315–5321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shichijo M, Kondo S, Ishimori M, Watanabe S, Helin H, Yamasaki T et al. (2006). PAR‐2 deficient CD4+ T cells exhibit downregulation of IL‐4 and upregulation of IFN‐gamma after antigen challenge in mice. Allergol Int 55: 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP et al. (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M, Corvera CU, Thoma MS, Kong W, McAlpine BE, Caughey GH et al. (1999). Proteinase‐activated receptor‐2 in human skin: tissue distribution and activation of keratinocytes by mast cell tryptase. Exp Dermatol 8: 282–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M, Vergnolle N, Young SH, Tognetto M, Amadesi S, Ennes HS et al. (2000). Agonists of proteinase‐activated receptor 2 induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism. Nat Med 6: 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen JY, Barry GD, Lohman RJ, Halili MA, Cotterell AJ, Le GT et al. (2012). Modulating human proteinase activated receptor 2 with a novel antagonist (GB88) and agonist (GB110). Br J Pharmacol 165: 1413–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen JY, Cotterell A, Lohman RJ, Lim J, Han A, Yau MK et al. (2014). Pathway‐selective antagonism of proteinase activated receptor 2. Br J Pharmacol 171: 4112–4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellani V, Kinsey AM, Prandini M, Hechtfischer SC, Reeh P, Magherini PC et al. (2010). Protease activated receptors 1 and 4 sensitize TRPV1 in nociceptive neurones. Mol Pain 6: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoes M, Oresic Bender K, Segal E, van der Linden WA, Syed S, Withana NP et al. (2013). Improved quenched fluorescent probe for imaging of cysteine cathepsin activity. J Am Chem Soc 135: 14726–14730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Bunnett NW, Sharkey KA, Brussee V, Compton SJ, Grady EF et al. (2001). Proteinase‐activated receptor‐2 and hyperalgesia: a novel pain pathway. Nat Med 7: 821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicuna L, Strochlic DE, Latremoliere A, Bali KK, Simonetti M, Husainie D et al. (2015). The serine protease inhibitor SerpinA3N attenuates neuropathic pain by inhibiting T cell‐derived leukocyte elastase. Nat Med 21: 518–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Moreau F, Hirota CL, MacNaughton WK (2010). Proteinase‐activated receptors induce interleukin‐8 expression by intestinal epithelial cells through ERK/RSK90 activation and histone acetylation. FASEB J 24: 1971–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wen S, Bunnett NW, Leduc R, Hollenberg MD, MacNaughton WK (2008). Proteinase‐activated receptor‐2 induces cyclooxygenase‐2 expression through beta‐catenin and cyclic AMP‐response element‐binding protein. J Biol Chem 283: 809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau MK, Liu L, Fairlie DP (2013). Toward drugs for protease‐activated receptor 2 (PAR2). J Med Chem 56: 7477–7497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Lieu T, Barlow N, Metcalf M, Veldhuis NA, Jensen DD et al. (2014a). Cathepsin S causes inflammatory pain via biased agonism of PAR2 and TRPV4. J Biol Chem 289: 27215–27234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Lieu T, Barlow N, Sostegni S, Haerteis S, Korbmacher C et al. (2015). Neutrophil elastase activates protease‐activated receptor‐2 (PAR2) and transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) to cause inflammation and pain. J Biol Chem 290: 13875–13887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Metcalf M, Bunnett NW (2014b). Biased signaling of protease‐activated receptors. Front Endocrinol 5: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]