Abstract

The prnD-prnB intergenic region regulates the divergent transcription of the genes encoding proline oxidase and the major proline transporter. Eight nucleosomes are positioned in this region. Upon induction, the positioning of these nucleosomes is lost. This process depends on the specific transcriptional activator PrnA but not on the general GATA factor AreA. Induction of prnB but not prnD can be elicited by amino acid starvation. A specific nucleosomal pattern in the prnB proximal region is associated with this process. Under conditions of induction by proline, metabolite repression depends on the presence of both repressing carbon (glucose) and nitrogen (ammonium) sources. Under these repressing conditions, partial nucleosomal positioning is observed. This depends on the CreA repressor's binding to two specific cis-acting sites. Three conditions (induction by the defective PrnA80 protein, induction by amino acid starvation, and induction in the presence of an activated CreA) result in similar low transcriptional activation. Each results in a different nucleosome pattern, which argues strongly for a specific effect of each signal on nucleosome positioning. Experiments with trichostatin A suggest that both default nucleosome positioning and partial positioning under induced-repressed conditions depend on deacetylated histones.

In simple eukaryotes, some genes are transcribed divergently from a common bidirectional promoter. Well-studied examples are the GAL1-GAL10 promoter of Saccharomyces cerevisiœ (reviewed in references 10 and 35) and the niiA-niaD promoter of Aspergillus nidulans (37, 41, 52). Here we analyzed the nucleosome rearrangements of the bidirectional prnD-prnB intergenic region. This is a 1.7-kb region located between the gene coding for proline oxidase (prnD) and the one coding for the major, specific proline transporter (prnB) (29, 50). These genes are located in the prn gene cluster in the right arm of chromosome VII (Fig. 1). The regulation of prnD and prnB involves a multiplicity of metabolic signals. The pathway-specific transcription factor PrnA is essential for proline induction of both genes (11, 21, 22, 46). The prnD-prnB intergenic region is a genuine bidirectional promoter, as mutations in the two PrnA binding sites present in this region affect the transcription of both prnD and prnB (21; I. García, D. Gómez, and C. Scazzocchio, unpublished results).

FIG. 1.

prnD-prnB intergenic region. prnD encodes proline oxidase, and prnB encodes the specific proline transporter (20, 28, 29, 50). The CreA-binding sites 3.1 and 3.2 (grey lozenges) are essential for prnB and indirectly for prnD repression (51, 15, 16). The AreA-binding sites 13 and 14 (grey ovals) are necessary to set the maximal level of transcription of prnB and to integrate carbon and nitrogen metabolite repression of this gene (24). High-affinity PrnA binding sites 2 and 3 are shown by white triangles; their occupancy upon induction by PrnA in vivo has been demonstrated (23). A putative binding site for a GCN4-like factor is shown as a thick arrow (56) A black triangle indicates the prnB TATA box (24). The positions of the transcriptional start points (+1) and of the ATG of prnD and prnB are shown (20, 50; S. Demais and C. Scazzocchio, unpublished results). Relevant restriction sites mentioned in the text are also shown.

Transcription of prnB but not of prnD can also be induced by amino acid starvation. This effect depends on the integrity of a canonical GCN4 binding site in the proximity of the prnB TATA box (56).

Repression of both prnB and prnD occurs only when both carbon (glucose) and nitrogen-repressing (ammonium) sources are present simultaneously (2, 5, 6, 21, 22). Repression acts directly on prnB expression, while repression of prnD is indirect and results from inducer exclusion (5, 16, 22). Repression necessitates both the activation of the negative regulator CreA and the inactivation of the GATA factor AreA. A model to account for this pattern of repression has been published previously (23). Figure 1 shows the prnD-prnB intergenic region with the cis-acting sites that have been shown to be physiologically relevant.

In this article we show that eight nucleosomes are positioned in the prnD-prnB region. Upon induction, these nucleosomes are no longer positioned, while a single nucleosome is partially positioned at a new location. In conditions of simultaneous carbon and nitrogen metabolite repression in the presence of inducer, a partial repositioning of nucleosomes occurs. We analyze in detail the role of the three transcription factors involved in prnD-prnB regulation, PrnA, CreA, and AreA, in this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

A pabaA1 strain was used as the wild type. creA loss-of-function strains were creAd1 pabaA1 (48) and creAd25 pabaA1 (4). The areA loss-of-function strain was areA600 biA1 sB43. areA600 is an early chain termination null mutation (1, 30). The prnA loss-of-function mutations analyzed in this work are listed in Table 1. Strains used were prnA404 pabaA1, prnA15 cnxJ1 pabaA1 fwA1, prnA80 pabaA1, prnA407 pabaA1 fwA, and prnA442 pabaA1 alcR125 fwA1. alcR125 is an alcR loss of function (43). For definitions of the standard genetic markers, see the Glasgow Stock List at http://www.gla.ac.uk/Acad/IBLS/molgen/aspergillus/strintro.html.

TABLE 1.

Sequence changes of the prnA mutations used in this work

| Mutation | Nucleotide sequence changea | Amino acid sequence changea | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| prnA15 | T(2209)C | L(621)P | This work |

| prnA80 | G(2319)C | A(658)P | This work |

| prnA407 | C(2101)A | S585Y | 11 |

| prnA442 | G(2744)T | AMB(819)Y+18-residue extension | This work |

| prnA469 | Insertion of G(1911) and deletion of C(1987) | Substitution of residues 522-547 | 11 |

| prnA404 | Deletion of 67-1510 | Deletion of residues 23-398 | 11, 12 |

Numbering of nucleotides and amino acids is that of Cazelle et al. (11).

Sequences of new prnA alleles.

The sequence changes of a number of prnA alleles were determined (Table 1). The approximate position in the gene in relation to deletion mutations was known (11, 46). Thus, the appropriate sequence was amplified by PCR with specific primers and the newly introduced changes were checked by sequencing (automatic sequencing; MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany).

Growth conditions.

A total of 106 spores of each strain per ml were inoculated at 37°C into liquid minimal medium with the appropriate supplements plus 0.1% fructose as the carbon source and 5 mM urea as the nitrogen source, except for the areA600 strain. Mycelia were grown for 8 h at 37°C and then incubated for 2 additional hours at 37°C or repressed with glucose (1%) and ammonium (20 mM ammonium-l[+]-tartrate), or induced with 20 mM l-proline, or induced with 20 mM l-proline and simultaneously either carbon repressed (1% glucose), nitrogen repressed (20 mM ammonium-l[+]-tartrate), or carbon and nitrogen repressed and incubated 2 h at 37°C. The areA600 strain was grown at 37°C in liquid minimal medium with the appropriate supplements plus 1% glucose and 5 mM ammonium-l(+)-tartrate for 7 h at 37°C, and then cultures were filtered and shifted to minimal medium containing the appropriate supplements and neutral carbon and nitrogen sources (5 mM urea and 0.1% fructose) without or with 20 mM proline and incubated for 2 additional hours at 37°C. An areA+ strain was grown in parallel in the same culture conditions. Mycelia were harvested by filtration through sterile Blutex tissue, washed with sterile distilled water, and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

RNA preparation and Northern blots.

Total RNA was isolated with the RNA Plus Extraction Solution (Biogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA electrophoresis and Northern blot hybridizations were carried out as described previously (22, 23). prnB, prnD, and acnA probes were prepared as described by Gómez et al. (22).

Nucleosome positioning.

Micrococcal nuclease I digestions were performed by the method adapted by Gonzalez and Scazzocchio (24). Micrococcal nuclease was used at concentrations ranging between 0.5 and 2.5 U/g of mycelium. DNA was digested with an appropriate restriction enzyme: PstI (SC1 hybridization) or HindIII (SC2 hybridization). Probe SC1 is the 389-bp PstI-AccI fragment of the prnD-prnB intergenic region (24). Probe SC2 is the 332-bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment of the prnD-prnB intergenic region (23).

For the restriction enzyme protection assay, a method adapted from Gregory et al. (25) was used (M. Mathieu, personal communication). Probe HP is the 836-bp HindIII-PstI fragment of bAN926, which contains a 907-bp fragment of the prnD open reading frame, the prnD-prnB intergenic region, and 1,512 bp of the prnB open reading frame (23). At least three independent experiments were carried out for each mutant and/or condition with identical results. In every case, induction and repression were checked by Northern blots made in parallel with the same mycelia.

In vivo footprinting.

Binding of PrnA to sites PrnA-2 and PrnA-3 was detected by in vivo footprinting as described by Gómez et al. (23) following the technique of Wolschek et al. (59).

RESULTS

Chromatin rearrangements in the prnD-prnB bidirectional promoter.

Throughout this article we compare three growth conditions: noninduced, absence of proline in a medium which contains nonrepressing carbon and nitrogen sources (under these conditions expression of prnD and prnB is minimal and virtually undetectable in Northern blots); induced, the same but in the presence of proline; and induced-repressed, where proline is added together with repressing nitrogen and carbon sources. The simultaneous presence of these repressing metabolites strongly diminishes transcription, but it does not abolish it (22, 51). While the exact experimental conditions are given in Materials and Methods, it is important to keep in mind the conceptual differences between the three conditions. When other conditions are used, these are defined in the text.

Under noninduced conditions, eight nucleosomes are positioned in the prnD-prnB promoter. This pattern is identical, under noninducing, nonrepressing (noninduced, defined above, Fig. 2), or repressing conditions (glucose and ammonium in the absence of proline, not shown). Upon induction (under nonrepressing conditions), nucleosome positioning is lost (Fig. 2). Between positions 904 and 1205, the pattern of micrococcal nuclease I cuts is different from that of the naked DNA and indicates that a nucleosome is partially positioned between these boundaries. The nuclease cut at position 1055 is much weaker under induced than noninduced conditions, which indicates that this nucleosome is positioned differently from either nucleosome +1 or +2 under noninducing conditions. The pattern of micrococcal nuclease I digestion does not allow us to conclude whether a new nucleosome is positioned between the cutting sites at nucleotides 510 and 725. However, the presence of a SacI restriction site in position 685 allowed us to investigate the positioning of this putative nucleosome. No protection of this restriction site is seen, and thus induction does not result in the positioning of an additional nucleosome (not shown) between these boundaries.

FIG. 2.

Nucleosome positioning in the prnD-prnB intergenic region. Numbers besides the autoradiograms correspond to the positions of the main cuts relative to the prnD ATG. These were calculated from molecular size markers run in every gel. Three conditions are shown. NI, noninduced, mycelia grown in the absence of proline in the absence of glucose and ammonium; I, proline-induced; IR, proline-induced in the presence of glucose and ammonium. (A) Pattern obtained with the SC1 probe (revealing the prnD proximal pattern). (B) Pattern obtained with the SC2 probe (revealing the prnB proximal pattern). These patterns are partially overlapping. Triangles, increasing concentration of micrococcal nuclease I. (C) Schematic representation of nucleosome positioning. Arrows indicate micrococcal nuclease I cuts. Their thickness indicates the relative intensity of the bands in the autoradiogram. Dashed arrows indicate weakly cut sites. White ovals represent fully positioned nucleosomes, while partially positioned nucleosomes are shown by diagonally hatched ovals (see text). The positions and lengths of the probes used are also indicated. Other symbols are as in Fig. 1. Under noninduced, repressed conditions (R, see text), the nucleosome pattern is identical to the one shown in the figure for the noninduced conditions. See Materials and Methods for exact growth conditions.

Addition of either glucose or ammonium, which singly do not result in significant repression (22, 23), does not affect the destabilization of nucleosome positioning seen in induced cultures; the pattern is identical to that found under induced conditions in the absence of any repressing metabolite (results not shown). When both glucose and ammonium are added to an induced culture, nucleosome positioning is seen for nucleosomes +2 to −4. The pattern is, except for nucleosome +1, which is fully positioned, one of partial positioning (see above), while the prnB proximal nucleosomes, +3 and +4, are not positioned at all. By partial positioning we mean that the pattern observed is what would be generated by superimposing the fully positioned and the fully nonpositioned patterns. The possible significance of this finding will be discussed below.

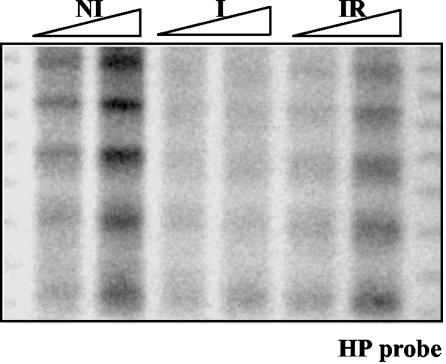

Induction results in nucleosome delocalization, not in complete nucleosome loss.

It is possible to differentiate between nucleosome delocalization and nucleosome loss if, rather than revealing micrococcal nuclease I cuts by indirect terminal labeling, one hybridizes a chromatin micrococcal nuclease I digest with a probe covering the whole region that is being analyzed. When this is done, the typical digestion ladder should be seen whether nucleosomes are positioned or not (J. L. Barra, personal communication).

The prnD-prnB intergenic region shows a typical nucleosome repeat under all induction and repression conditions, with a length of ≈160 bp, the length previously reported for Aspergillus nidulans (24, 36, 42). This is shown for the prnB-proximal region in Fig. 3. Note that under induction conditions the bands became fuzzy and that this effect it more pronounced the longer the polynucleosome is. This is exactly what is to be expected if in a given segment of DNA nucleosomes is present but not translationally positioned, the distribution of sizes obtained by digestion being broader the larger the number of nucleosomes. Bands are fuzzy in induced conditions, clear in noninduced conditions, and intermediate under induced-repressed conditions. The latter finding supports the data obtained (Fig. 2) with indirect terminal labeling, which corresponds to a pattern of partial positioning for the induced-repressed conditions (see Discussion). Other blots, hybridized with suitable probes, show the same pattern for the whole intergenic region (not shown). As this experiment does not distinguish individual nucleosomes, it cannot be excluded that some nucleosomes may be lost and some delocalized, nor can it be excluded that the population of nuclei be heterogeneous vis à vis these two possibilities.

FIG. 3.

Presence of nucleosomes in the prnD-prnB promoter, independent of positioning. We show here only the prnB proximal region (bp 998 to 1834 from the prnD ATG) NI, I, and IR are as in Fig. 2.

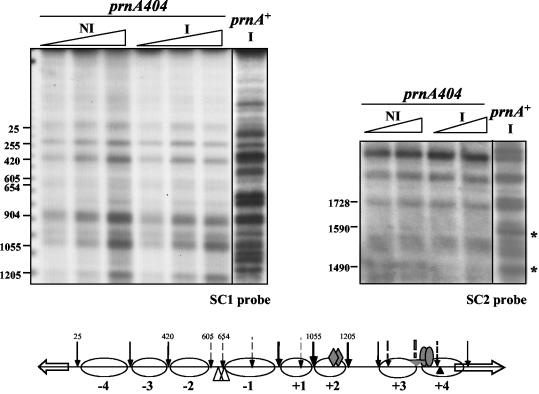

PrnA is necessary for nucleosome delocalization upon induction.

Figure 4 shows that in a deletion of prnA, all nucleosomes remain completely positioned upon induction. A number of prnA mutants outside the DNA binding domain have been characterized (11, 12, 46; this article). We investigated whether any of these mutants, unable to activate prnD and prnB transcription, as assessed by Northern blots, maintain the ability to delocalize nucleosomes. The sequence changes of these mutations are shown in Table 1. All mutations tested, with the exception of prnA80, are unable to elicit transcription and nucleosome delocalization (not shown). The binding of some PrnA mutant proteins to high-affinity sites 2 and 3 (23) was also investigated by in vivo methylation protection. The results are shown in Fig. 5. All mutations tested, with the exception of prnA80, resulted in inability to bind both PrnA sites 2 and 3. prnA80 does not affect the binding to either site 2 or 3. The prnA80 mutant was classified as cryosensitive in growth tests (46); it equally affects transcription of prnD at 37°C and at 25°C, while showing a cryosensitive phenotype for prnB transcription (Fig. 6A). At the level of chromatin, a prnA80 strain behaves exactly like a prnA+ strain: upon induction all nucleosomes are delocalized and a nucleosome is newly (and partially) positioned between nucleotides 904 and 1205 (Fig. 6B). The significance of these results will be discussed below.

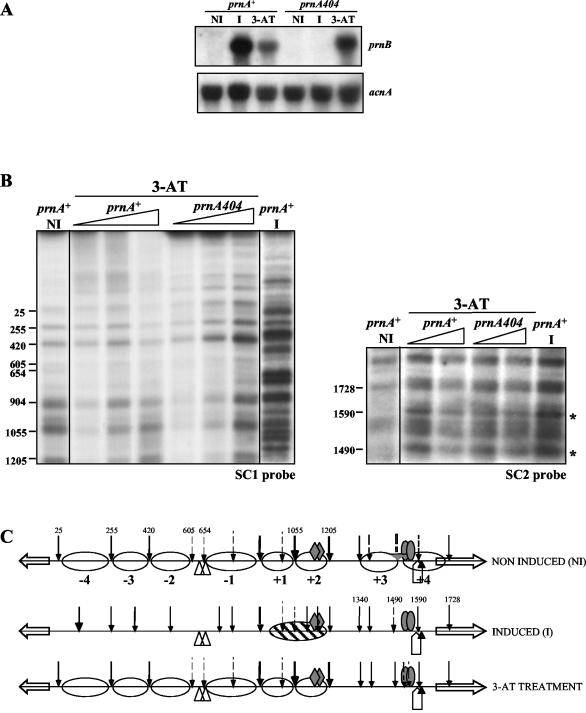

FIG. 4.

Nucleosome positioning in a prnA deletion. For comparison, the micrococcal nuclease I protection pattern of a prnA+ strain grown under inducing conditions is also shown. Left, SC1 probe; right, SC2 probe. Asterisks indicate the positions of the relevant changes observed with probe SC2. Symbols are as in Fig. 1 and 2. No transcription of either prnD or prnB is seen in this mutant (shown for prnB also in Fig. 7). Bottom panel, schematic representation of nucleosome positioning in a prnA404 mutant, which was the same under noninduced and induced conditions.

FIG. 5.

In vivo footprints of a number of prnA mutants. Left panel, in vivo footprints of a prnA+ and a prnA442 strain (prnD coding strand shown). Right panel, in vivo footprint pattern of a number of prnA missense mutants. The prnA404 deletion mutant is also included as a control. Footprints of a prnA+ strain under both noninducing and inducing conditions are also shown. All mutant strains were grown under inducing conditions (prnD coding strand shown). The sequence corresponding to PrnA binding sites 2 and 3 is shown to the side of the autoradiograms. The protected G's in PrnA binding sites 2 and 3 are indicated in bold in the sequence and by arrows pointing to the autoradiogram. Symbols are as in Fig. 2. Nucleotide and amino acid changes in each mutant are shown in Table 1.

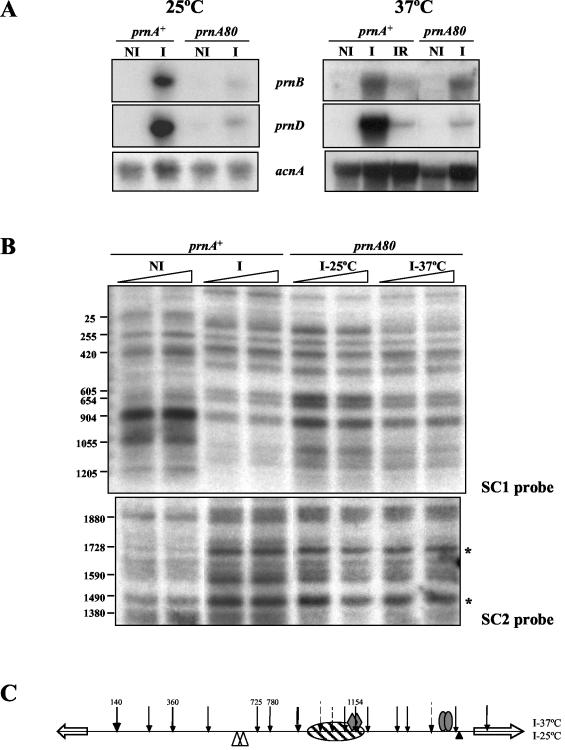

FIG. 6.

Transcription and nucleosomal rearrangements in a prnA80 mutant. (A) Northern blots of mycelia grown at 25 and 37°C. (B) Micrococcal nuclease I digestion of the prnA80 induced mycelia at 25 and 37°C. For comparison, the prnA+ strain grown at 25°C is shown. This is identical to the pattern obtained for prnA+ at 37°C (Fig. 2 and Fig. 4). (C) Schematic representation of nucleosome positioning of a prnA80 mutant grown under inducing conditions at both 25 and 37°C. Asterisks indicate the positions of the relevant changes observed with probe SC2. Other symbols are as in Fig. 2.

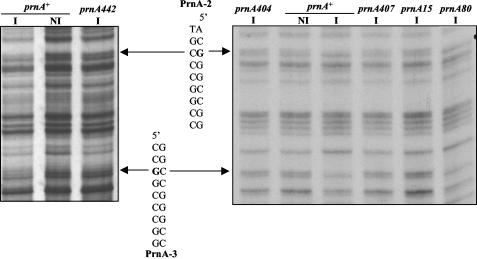

Induction of prnB transcription by amino acid starvation results in loss of positioning of prnB proximal nucleosomes.

The transcription of prnB (but not of prnD) can be elicited independently from proline induction by amino acid starvation, possibly mediated by a GCN4-like factor (56). This activation is lower, but noticeable, in a strain with prnA deleted (56). We used 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole, a competitive inhibitor of the histidine biosynthetic enzyme His3p, to induce amino acid starvation (as in reference 56). Under these conditions, the positioning of the prnB proximal nucleosomes +3 and +4 is lost (Fig. 7). All other nucleosomes remained positioned as they are under noninduced conditions. This chromatin rearrangement is identical in prnA+ and prnA404 strains.

FIG. 7.

Transcriptional activation and nucleosome positioning under conditions of amino acid starvation. (A) Northern blot. (B) Patterns obtained after micrococcal nuclease I treatment of mycelia grown in the presence of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT). For comparison, patterns of a prnA+ strain grown in noninduced and induced conditions are also shown. All other symbols are as in Fig. 2. Asterisks indicate the bands resulting from micrococcal nuclease I cuts and revealed by the SC2 probe that appear under conditions of both proline and 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole induction and that show loss of positioning of nucleosomes +3 and +4. (C) Schematic representation of nucleosome positioning of both prnA+ and prnA404 strains grown in the presence of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole.

AreA is not necessary for chromatin remodeling upon induction.

The GATA factor AreA is necessary to achieve the maximal levels of transcription of prnB and prnD (22). We investigated here the role of AreA in nucleosome positioning upon induction. Under both inducing and noninducing conditions, the nucleosomal pattern is the same in areA+ and areA600 strains (Fig. 8).

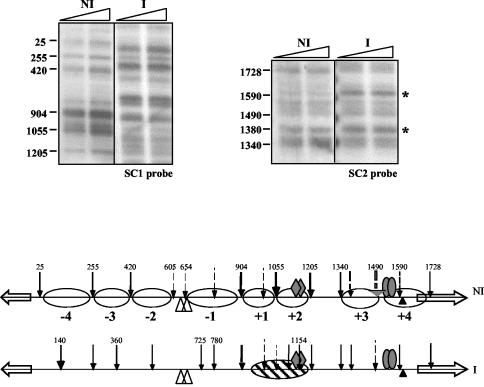

FIG. 8.

Micrococcal nuclease I digestion pattern of an areA600 mutant. Noninduced and induced conditions are shown. Symbols are as in Fig. 2. The growth conditions used to permit the growth of the areA600 strain are different from those used in other experiments (see Materials and Methods). Under the same growth conditions, the areA+ strain behaves exactly as shown in Fig. 2 for noninduced and induced cultures (not shown). Asterisks indicate the positions of the relevant changes observed with probe SC2. Other symbols are as in Fig. 2.

CreA is essential for nucleosome positioning upon repression but is not involved in the establishment of the default chromatin structure.

The creA loss-of-function mutant creAd1, which bears a point mutation in the DNA binding domain (48), results in complete derepression of prnB and prnD (Fig. 9A). Figure 9B shows that the nucleosome positioning associated with repression depends strictly on CreA. The pattern of nucleosome positioning in creA mutant strains is the same under induced nonrepressed and induced-repressed conditions and identical to the wild-type pattern obtained under induced conditions. creAd25, a mutation in the carboxy terminus of the protein which results specifically in derepression of prnB and prnD but not of alcR and alcA (4; B. Cubero, M. Mathieu, B. Felenbok, and C. Scazzocchio, unpublished results) has the same effect on nucleosomal positioning as the more extreme creAd1 mutation (not shown). Figure 9B also shows the chromatin pattern obtained under noninduced conditions in creA-derepressed mutants, which are identical to the one obtained in creA+ strains grown in the same conditions. This demonstrates that CreA is not involved in default nucleosome positioning.

FIG. 9.

Nucleosome patterns of derepressed mutants. (A) Northern blot of prnB and prnD mRNAs in creA+ and creAd1 strains. (B) Micrococcal nuclease I protection pattern of the creAd1 strain. For probe SC2, the induced-repressed pattern is not shown, as the pattern under induced-repressed conditions does not differ from the pattern under induced conditions in this region in a creA+ strain (see Fig. 2). The pattern of a creA+ strain grown under noninduced conditions is also shown. (C) Micrococcal nuclease I pattern of a cis-derepressed mutant (prnd22). For comparison, the pattern obtained for a prn+ strain in induced and induced-repressed conditions is shown. (D) Schematic representation of nucleosome positioning in both creAd1 and prnd22 strains grown under inducing and inducing-repressing conditions. Asterisks indicate the positions of the relevant changes observed with probe SC2. Other symbols are as in Fig. 2. The creAd1 and the prnd22 mutants show the same noninduced (noninduced, repressed) position pattern as the wild type (not shown).

We constructed a double creA prnA loss-of-function mutant (prnA404 creAd1). Northern blots and chromatin analysis were carried out, showing that the prnA404 deletion is completely epistatic to a creAd1 mutation for both transcriptional activation and nucleosome delocalization (not shown).

Nucleosome positioning upon repression does not occur in cis-derepressed mutants.

Mutations in CreA-binding sites 3.1 and 3.2 (prnd22 and prnd20, respectively) have shown these sites to be essential for CreA-mediated repression (3, 5, 15, 51). Figure 9C shows that the nucleosome positioning pattern in a prnd22 mutant is the same under induced and induced-repressed conditions, indicating that the partial positioning of nucleosomes −4 to −1 does not occur when this site is mutated. Experiments with prnd20 and the prnd22 prnd20 double mutant gave identical results (not shown). Thus, mutation at these sites results in the same chromatin pattern as mutations in the CreA trans-acting factor.

Histone deacetylation is involved in default and CreA-promoted nucleosome positioning.

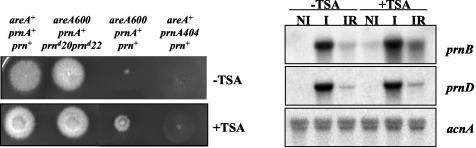

creAd mutations suppress areA loss-of-function mutations for the utilization of proline in the presence of a repressive carbon source (2, 8). This happens because AreA is only necessary for prnB transcription in the presence of an active CreA-repressing protein (2, 23, 24). We found that the presence of trichostatin A, an inhibitor of histone deacetylation (61), results in a similar phenotypic suppression of an areA null mutation (Fig. 10A). For analogous reasons, creAd mutations also suppress areA loss-of-function mutations for the utilization of acetamide and γ-aminobenzoic acid as nitrogen sources in the presence of glucose. We thus checked whether trichostatin A results in a similar phenotypic suppression of an areA null mutation on the latter nitrogen sources. We could not see any phenotypic suppression on either acetamide or γ-aminobenzoic as the nitrogen source at a trichostatin A concentration identical to that used in Fig. 10A. Higher concentrations were too toxic to be tested usefully (not shown).

FIG. 10.

Trichostatin A treatment. Left, growth tests showing partial suppression of an areA600 mutation. The medium contains proline as the sole nitrogen source plus glucose as the sole carbon source. The relevant genotypes of strains are indicated above the growth tests. Right, Northern blots showing the effect of trichostatin A on prnB and prnD expression. −TSA, no trichostatin A; +TSA, 3.3 μM trichostatin A.

We then investigated the effect of trichostatin A on both transcription and nucleosome positioning (Fig. 10B and Fig. 11). The presence of trichostatin A results in an elevated basal level of prnB but not prnD transcription. Proline affords optimal induction independently of the presence of the drug. As predicted by the partial suppression of an areA mutation by trichostatin A, transcription of prnB and, to a lesser extent, prnD is partially derepressed when the drug is added to the culture medium. Trichostatin A results in specific changes in the pattern of nucleosome positioning. In the presence of trichostatin A in noninduced conditions, positioning of nucleosomes +1 to +4 is completely lost and nucleosomes −1, −3, and −4 are only partially positioned. It may be relevant that nucleosome +4 occludes the prnB TATA box. This result is shown in Fig. 11.

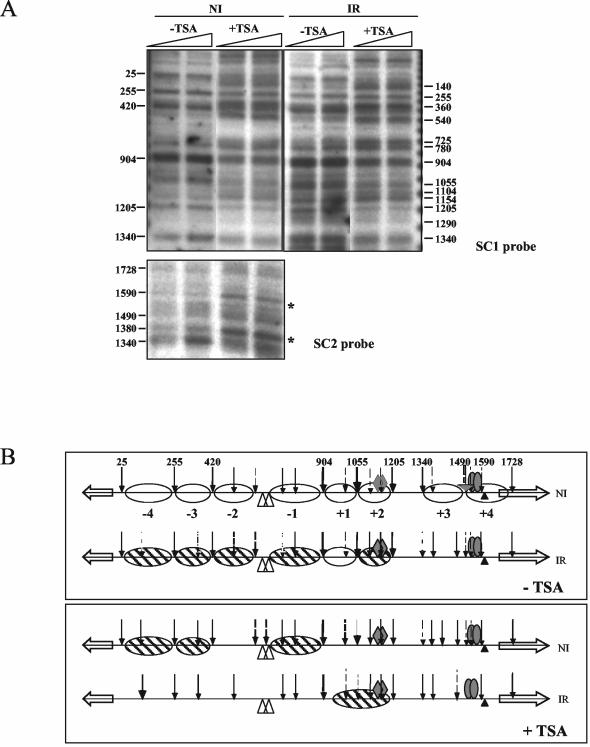

FIG. 11.

Effect of trichostatin A on nucleosome positioning. (A) Micrococcal nuclease I patterns. In noninduced (NI) conditions, under trichostatin A (TSA) treatment, nucleosomes +2 and −1 to −4 are partially positioned (probe SC1), and nucleosome +3 and +4 positioning is lost (probe SC2). In induced-repressed (IR) conditions, positioning of nucleosomes −4 to +2 is lost after trichostatin A treatment, as revealed with probe SC1. For probe SC2, the induced-repressed pattern is not shown, as in this region the pattern under induced-repressed conditions does not differ from the pattern under induced conditions (see Fig. 2). Under induced (I) conditions, the patterns obtained in the presence of trichostatin A are identical to those found in its absence (Fig. 2) and thus are not shown. Asterisks indicate the positions of the relevant changes observed with probe SC2. (B) Schemes comparing nucleosome positioning under noninduced and induced-repressed conditions in the presence and absence of trichostatin A. Symbols are as in Fig. 2. −TSA, no trichostatin A; +TSA, 3.3 μM trichostatin A. As trichostatin A is prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide, controls without trichostatin A were treated with equivalent amounts of this solvent.

The most striking differences, however, are found under inducing-repressing conditions. Trichostatin A treatment results in total loss of nucleosome positioning; that is, the same result as obtained for a creA-derepressed mutant (Fig. 11, compare with Fig. 8). There is complete agreement between the partial phenotypic suppression of areA600 by trichostatin A, the levels of transcription, and nucleosome positioning in the prnD-prnB region. These results suggest that CreA-mediated repression acts via histone deacetylation.

DISCUSSION

Loss of nucleosome positioning in prnD-prnB depends on the specific activator PrnA and is independent of the GATA factor AreA.

Transcriptional activation is often accompanied by a loss of nucleosome positioning. Usually, specific transcription factors are necessary for this process (7, 53, 57), the niiA-niaD promoter of A. nidulans being an interesting exception (37). In the prnD-prnB promoter, loss of nucleosome positioning requires an active PrnA protein. Chromatin rearrangements may be elicited directly or indirectly by transcription factors or could be merely a passive result of transcription. Of the eight nucleosomes in the prnD-prnB intergenic region, only nucleosomes +4 and −4 overlap the initiation of transcription. The progress of RNA polymerase has been shown to result in positive DNA supercoiling downstream and negative DNA supercoiling upstream of its site of action (34). Positive supercoiling but not negative supercoiling has been associated with nucleosome destabilization (32, 33). On the contrary, negative supercoiling has been associated with nucleosome stability (38). Thus, it is extremely unlikely that the delocalization of nucleosomes +3 to −3 could be in any way related to topological alterations in the DNA resulting passively from transcription.

In other experimental systems, mutations in the TATA box have been used to investigate the dependence of chromatin rearrangements on transcriptional activation (18, 47), but this is not possible in this promoter, because a deletion of the putative prnB TATA box does not abolish transcription (22) and there is no obvious prnD TATA box. To discriminate the transcriptional activation function of PrnA from its chromatin remodeling function, we have taken advantage of a number of mutations available outside the DNA binding domain (Table 1). All these mutants were tested for transcriptional activation and chromatin rearrangement activity. We failed to find a mutant that had completely lost transcriptional activation while maintaining chromatin remodeling. Nevertheless, the results with prnA80 strongly suggest that these functions are indeed separable. This mutation results in greatly impaired transcriptional activation, but chromatin remodeling occurs exactly as in a prnA+ strain. The transcription of prnB and prnD in prnA80 mutants is as low as that found under induced-repressed conditions in the wild type. Under the latter conditions, we see an intermediate pattern of nucleosome positioning (see below). The fact that complete loss of nucleosome positioning occurs in prnA80 strains in spite of the strongly diminished transcription of prnB and prnD argues strongly for a specific effect of PrnA on nucleosomal delocalization and, by the same token, for a specific role of CreA on nucleosome positioning under inducing-repressing conditions (see below).

prnB transcription can also be induced by amino acid starvation. While we have not shown by mutational analysis that a GCN4 homologue is directly involved in chromatin restructuring, this was previously shown for the transcriptional activation elicited by amino acid starvation (56). A mutation in a putative Gcn4p-like binding site abolishes this alternative induction process but not PrnA-mediated proline induction. There is a close homologue of GCN4 in A. nidulans (CpcA) (58), and thus it is very likely that this is the transcription factor involved (56). Gcn4p has been shown to be involved in destabilization of nucleosome positioning in the HIS3 and PHO5 promoters (31, 55). This protein interacts physically with coactivators such as Gcn5p and other proteins of the SAGA and the SWI/SNF complexes (reference 54 and references therein).

The prnB transcription levels elicited by amino acid starvation are considerably higher than those found in a prnA80 mutant induced by proline, where loss of nucleosome positioning is complete. What is relevant here is that two different induction processes, mediated necessarily by different transcription factors, result in different chromatin rearrangements and that these are not correlated with the levels of transcript. A similar uncoupling of transcriptional activation and nucleosomal rearrangement has been observed in mutants resulting in derepression of the SUC2 promoter of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (19).

The GATA factor AreA is totally irrelevant for nucleosome delocalization upon induction in the prnD-prnB promoter. This contrasts with its essential role in the niiA-niaD promoter (37). Ammonium repression on its own does not lead to nucleosome positioning in the prnD-prnB promoter. As ammonium repression prevents AreA function (30, 40) this is consistent with the fact that AreA is not necessary for nucleosome delocalization upon induction.

Partial positioning of nucleosomes upon repression depends on the CreA repressor.

Positioning of nucleosomes under noninduced conditions is independent from the presence of the CreA repressor. A specific pattern of nucleosome positioning, different from the default pattern and from the fully induced pattern, is seen under inducing-repressing conditions (see below). Positioning upon simultaneous glucose and ammonium repression requires CreA. This has been shown by using mutations in both the CreA protein itself and in its cognate binding sites in the prnD-prnB promoter. The comparison of these results with those obtained with the prnA80 mutant demonstrates that the partial positioning found under induced-repressed conditions is specific (see above).

We have shown by in vivo methylation protection experiments that under conditions of CreA-mediated repression, PrnA remains bound to the high-affinity sites 2 and 3 (Fig. 8 in reference 21). This implies that CreA acts by negating PrnA interactions with the transcriptional and chromatin remodeling complexes rather than by preventing its binding to DNA.

Under conditions of CreA-mediated repression, positioning of nucleosomes +3 and +4 is completely lost, nucleosome 1 is positioned, and nucleosomes −4 to −1 and +2 show a pattern of partial positioning (see Fig. 2 and Results section). A similar pattern of partial positioning has been obtained for the PHO8 promoter in S. cerevisae (9). This pattern can be due either to an “oscillation” in the state of each nucleosome or to a heterogeneity in the nuclear population, in which some nuclei show an “open” and others a “closed” chromatin pattern. We favor the first alternative. Nuclear heterogeneity would imply that the intracellular concentration of CreA is limiting. It is unlikely for a protein that represses every single gene sensitive to carbon catabolite repression to be present in limiting concentrations. Limiting concentrations of transcription factors lead to codominance of loss-of-function mutations when tested in diploids with their wild-type allele (6, 14, 44, 45), while creAd (loss of function) mutations are clearly recessive (8).

In S. cerevisae, Mig1, the specific carbon catabolite repressor, acts by recruiting the Tup1-Ssn6 complex, and this in its turn acts directly on chromatin structure, and specifically on H3 acetylation (17, 27; reviewed in references 49 and 60). One cannot, however, extrapolate directly from S. cerervisae to A. nidulans. CreA shows similarity to Mig1 only in its DNA binding domain. RcoA, the only clear Tup1 homologue present in the A. nidulans genome, is not involved in carbon catabolite repression of either the prn cluster or the alc regulon (26; I. García, M. Mathieu, B. Felenbok, and C. Scazzocchio, unpublished data). Its role will be analyzed in detail in another publication.

Both default nucleosome positioning and positioning upon repression are probably dependent on deacetylation.

Trichostatin A treatment results in loss of positioning of nucleosomes +1 to +4 and very mild transcriptional activation of prnB in the absence of induction by proline. This implies that the deacetylation of histones plays a role in the default positioning of at least some nucleosomes in the prnD-prnB promoter. Among the nucleosomes delocalized by trichostatin A treatment, we find nucleosome +4, the one that occludes the prnB TATA box. Previous work has shown that this element is not essential for prnB transcriptional activation, but that its deletion leads to halving the steady-state level of the prnB mRNA (22). A striking effect of trichostatin A is seen under conditions of repression (induced-repressed). Here we see total loss of nucleosome positioning and partial derepression. However, the derepression observed is not nearly as drastic as that seen in a creAd mutation. This implies that while nucleosome repositioning may be necessary for full repression, CreA can still partially repress on completely open chromatin.

The work presented here is an analysis of the chromatin structure of a region subject to a multiplicity of transcription signals in a simple eukaryote. The prnD-prnB promoter integrates four different signals, proline induction, amino acid starvation, and nitrogen and carbon metabolite repression. This level of complexity is higher than that found in some other well-studied promoters, such as GAL1-GAL10 of S. cerevisiae and niiA-niaD of Aspergillus nidulans. We have been able to discriminate between the roles of the different transcription factors involved on nucleosome positioning. Transcription factors act on chromatin structure by recruiting remodeling and acetylation complexes (see reference 39 for a review). The availability of the complete genomic sequence of A. nidulans and of new methods simplifying the procedures for gene inactivation (13; K.-H. Han, Z. Hamari, J.-H. Seo, C. Scazzocchio, and J.-H. Yu, unpublished results) will permit us to study systematically the involvement of these complexes and their interaction with a multiplicity of transcription factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank José L. Barra for suggesting the experiment used to discriminate nucleosome delocalization from complete nucleosome loss and Martine Mathieu and Béatrice Felenbok for communicating their adaptation (25) before publication. We thank Rafael Fernández for help and discussion and Beatriz Cubero for critical reading of the manuscript.

I.G. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from, successively, the Spanish Ministry of Education and the EU Marie Curie Programme. R.G. was the recipient of postdoctoral fellowships from, successively, the EMBO and the EU Marie Curie Programme. D.G. was supported by a predoctoral scholarship from the French Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer. This work was supported by the Université Paris-Sud, the CNRS, the IUF, and EU contract BIO4-CT96-0535.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al Taho, N., H. N. Sealy-Lewis, and C. Scazzocchio. 1984. Suppressible alleles in a positive control gene in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Genet. 8:245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arst, H. N., Jr., and D. J. Cove. 1973. Nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 126:111-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arst, H. N., Jr., and D. W. MacDonald. 1975. A gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans with an internally located cis-acting regulatory region. Nature 254:26-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arst, H. N., Jr., and C. R. Bailey. 1977. The regulation of carbon metabolism in Aspergillus nidulans, p. 131-146. In J. E. Smith and J. A. Pateman (ed.), Genetics and physiology of Aspergillus. Academic Press, London, England.

- 5.Arst, H. N., Jr., D. W. MacDonald, and S. A. Jones. 1980. Regulation of proline transport in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 116:285-294. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arst, H. N., Jr., and C. Scazzocchio. 1985. Formal genetics and molecular biology of the control of gene expression in Aspergillus nidulans, p. 309-343. In J. W. Bennet and L. L. Lasure (ed.), Gene manipulations in fungi. Academic Press, Orlando, Fla.

- 7.Axelrod, J. D., M. S. Reagan, and J. Majors. 1993. GAL4 disrupts a repressing nucleosome during activation of GAL1 transcription in vivo. Genes Dev. 7:857-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey, C., and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1975. Carbon catabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Eur. J. Biochem. 51:573-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbaric, S., K. D. Fascher, and W. Hörz. 1992. Activation of the weakly regulated PHO8 promoter in S. cerevisiae: chromatin transition and binding sites for the positive regulatory protein PHO4. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1031-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bash, R., and D. Lohr. 2001. Yeast chromatin structure and regulation of GAL gene expression. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 65:197-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cazelle, B., A. Pokorska, E. Hull, P. M. Green, G. Stanway, and C. Scazzocchio. 1998. Sequence, exon-intron organization, transcription and mutational analysis of prnA, the gene encoding the transcriptional activator of the prn gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 28:355-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cazelle, B., A. Pokorska, E. Hull, P. M. Green, G. Stanway, and C. Scazzocchio. 1999. Sequence, exon-intron organization, transcription and mutational analysis of prnA, the gene encoding the transcriptional activator of the prn gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans (erratum). Mol. Microbiol. 31:1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaveroche M. K., J. M. Ghigo, and C. d'Enfert. 2000. A rapid method for efficient gene replacement in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:E97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cove, D. J. 1966. The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 113:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cubero, B., and C. Scazzocchio. 1994. Two different adjacent and divergent zinc-finger binding sites are necessary for CREA-mediated carbon catabolite repression in the proline gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 13:407-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cubero, B., D. Gómez, and C. Scazzocchio. 2000. Metabolite repression and inducer exclusion in the proline utilization gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 182:233-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edmonson, D. G., M. M. Smith, and S. Y. Roth. 1996. Repression domain of the yeast global repressor Tup1p interacts directly with histones H3 and H4. Genes Dev. 10:1247-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fascher, K. D., J. Schmitz, and W. Hörz. 1993. Structural and functional requirements for the chromatin transition at the PHO5 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae upon PHO5 activation. J. Mol. Biol. 231:658-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavin, I. M., and R. T. Simpson. 1997. Interplay of yeast global transcriptional regulators Ssn6p-Tup1p and Swi-Snf and their effect on chromatin structure. EMBO J. 16:6263-6271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gavrias, V. 1992. Etudes moléculaires sur la régulation et la structure du groupe de gènes prn chez Aspergillus nidulans. Ph.D. thesis. Université Paris-Sud XI, Orsay, France.

- 21.Gómez, D., B. Cubero, G. Cecchetto, and C. Scazzocchio. 2002. PrnA, a Zn2Cys6 activator with a unique DNA recognition mode, requires inducer for in vivo binding. Mol. Microbiol. 44:585-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gómez, D., I. García, C. Scazzocchio, and B. Cubero. 2004. Multiple GATA sites: protein binding and physiological relevance for the regulation of the proline transporter gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 50:277-289. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gonzalez, R., V. Gavrias, D. Gómez, C. Scazzocchio, and B. Cubero. 1997. The integration of nitrogen and carbon catabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans requires the GATA factor AreA and an additional positive-acting factor, ADA. EMBO J. 16:2937-2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez, R., and C. Scazzocchio. 1997. A rapid method for chromatin structure analysis in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Nucleic Acid Res. 25:3955-3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregory, P. D., A. Schmid, M. Zavari, M. Munsterkotter, and W. Horz. 1999. Chromatin remodelling at the PHO8 promoter requires SWI-SNF and SAGA at a step subsequent to activator binding. EMBO J. 18:6407-6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hicks, J., R. A. Lockington, J. Strauss, D. Dieringer, C. P. Kubicek, J. Kelly, and N. Keller. 2001. RcoA has pleiotropic effects on Aspergillus nidulans cellular development. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1482-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, L., W. Zhang, and S. Y. Roth. 1997. Amino termini of histones H3 and H4 are required for a1-α2 repression in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6555-6562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hull, E. P., P. M. Green, H. N. Arst, Jr., and C. Scazzocchio. 1989. Cloning and physical characterisation of the L-proline catabolism gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 3:553-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones, S. A., H. N. Arst, Jr., and D. W. MacDonald. 1981. Gene roles in the prn cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Genet. 27:150-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kudla, B., M. X. Caddick, T. Langdon, N. M. Martinez-Rossi, C. F. Bennett, S. Sibley, R. W. Davies, and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1990. The regulatory gene areA mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mutations affecting specificity of gene activation alter a loop residue of a putative zinc finger. EMBO J. 9:1355-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, Y., and D. J. Clark. 2002. SWI/SNF-dependent long-range remodeling of yeast HIS3 chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:15381-15386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, M. S., and W. T. Garrard. 1991. Transcription-induced nucleosome ‘splitting’: an underlying structure for DNase I sensitive chromatin. EMBO J. 10:607-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, M. S., and W. T. Garrard. 1991. Positive DNA supercoiling generates a chromatin conformation characteristic of highly active genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:9675-9679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, L. F., and J. C. Wang. 1987. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:7024-7027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lohr, D., P. Venkov, and J. Zlatanova. 1995. Transcriptional regulation in the yeast GAL gene family: a complex genetic network. FASEB J. 9:777-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris, N. R. 1976. Nucleosome structure in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell 8:357-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muro-Pastor, M. I., R. Gonzalez, J. Strauss, F. Narendja, and C. Scazzocchio. 1999. The GATA factor AreA is essential for chromatin remodelling in an eukaryotic bidirectional promoter. EMBO J. 18:1584-1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterton, H. G., and C. von Holt. 1993. Negative supercoiling and nucleosome cores. I. The effect of negative supercoiling on the efficiency of nucleosome core formation in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 229:623-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterson, C. L., and C. Logie. 2000. Recruitment of chromatin remodeling machines. J. Cell. Biochem. 78:179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Platt, A., T. Langdon, H. N. Arst, Jr., D. Kirk, D. Tollervey, J. M. Sanchez, and M. X. Caddick. 1996. Nitrogen metabolite signalling involves the C terminus and the GATA domain of the Aspergillus transcription factor AREA and the 3′ untranslated region of its mRNA. EMBO J. 15:2791-2801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Punt, P. J., J. Strauss, R. Smit, J. R. Kinghorn, C. A. van den Hondel, and C. Scazzocchio. 1995. The intergenic region between the divergently transcribed niiA and niaD genes of Aspergillus nidulans contains multiple NirA binding sites which act bidirectionally. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5688-5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramón, A., M. I. Muro-Pastor, C. Scazzocchio, and R. Gonzalez. 2000. Deletion of the unique gene encoding a typical histone H1 has no apparent phenotype in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 35:223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts, T., S. Martinelli, and C. Scazzocchio. 1979. Allele specific, gene unspecific suppressors in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 177:57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scazzocchio, C., N. Sdrin, and G. Ong. 1982. Positive regulation in a eukaryote, a study of the uaY gene of Aspergillus nidulans. I. Characterization of alleles, dominance and complementation studies, and a fine structure map of the uaY-oxpA cluster. Genetics 100:185-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scazzocchio, C. 1994. The proline utilisation pathway, history and beyond. Prog. Ind. Microbiol. 29:259-277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma, K. K., and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1985. The product of the regulatory gene of the proline catabolism gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans is a positive-acting protein. Curr. Genet. 9:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen, C. H., B. P. Leblanc, J. A. Alfieri, and D. J. Clark. 2001. Remodeling of yeast CUP1 chromatin involves activator-dependent repositioning of nucleosomes over the entire gene and flanking sequences. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:534-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shroff, R. A., R. A. Lockington, and J. M. Kelly. 1996. Analysis of mutations in the creA gene involved in carbon catabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Can. J. Microbiol. 42:950-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith, R. L., and A. D. Johnson. 2000. Turning genes off by Ssn6-Tup1: a conserved system of transcriptional repression in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sophianopoulou, V., and C. Scazzocchio. 1989. The proline transport protein of Aspergillus nidulans is very similar to amino acid transporters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 3:705-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sophianopoulou, V., T. Suarez, G. Diallinas, and C. Scazzocchio. 1993. Operator derepressed mutations in the proline utilisation gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 236:209-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strauss, J., M. I. Muro-Pastor, and C. Scazzocchio. 1998. The regulator of nitrate assimilation in ascomycetes is a dimer which binds a nonrepeated, asymmetrical sequence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1339-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Svaren, J., and W. Hörz. 1997. Transcription factors vs nucleosomes: regulation of the PHO5 promoter in yeast. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:93-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swanson, M. J., H. Qiu, L. Sumibcay, A. Krueger, S. J. Kim, K. Natarajan, S. Yoon, and A. G. Hinnebusch. 2003. A multiplicity of coactivators is required by Gcn4p at individual promoters in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:2800-2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Syntichaki, P., I. Topalidou, and G. Thireos. 2000. The Gcn5 bromodomain coordinates nucleosome remodelling. Nature 404:414-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tazebay, U. H., V. Sophianopoulou, C. Scazzocchio, and G. Diallinas. 1997. The gene encoding the major proline transporter of Aspergillus nidulans is upregulated during conidiospore germination and in response to proline induction and amino acid starvation. Mol. Microbiol. 24:105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verdone, L., F. Cesari, C. L. Denism, E. Di Mauro, and M. Caserta. 1997. Factors affecting Saccharomyces cerevisiae ADH2 chromatin remodelling and transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 272:30828-30834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wanke, C., S. Eckert, G. Albrecht, W. van Hartingsveldt, P. J. Punt, C. A. van den Hondel, and G. H. Braus. 1997. The Aspergillus niger GCN4 homologue, cpcA, is transcriptionally regulated and encodes an unusual leucine zipper. Mol. Microbiol. 23:23-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolschek, M. F., F. Narendja, J. Karlseder, P. Kubicek, C. Scazzocchio, and J. Strauss. 1998. In situ detection of protein-DNA interactions in filamentous fungi by in vivo footprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:3862-3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu, J., N. Suka, M. Carlson, and M. Grunstein. 2001. TUP1 utilizes histone H3/H2B-specific HDA1 deacetylase to repress gene activity in yeast. Mol. Cell 7:117-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshida, M., M. Kijima, M. Akita, and T. Beppu. 1990. Potent and specific inhibition of mammalian histone deacetylase both in vivo and in vitro by trichostatin A. J. Biol. Chem. 265:17174-17179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]