Abstract

Summary

Consecutive admissions of 214 women with borderline personality disorder were investigated for patterns of specific forms of self-harm and reported developmental experiences. Systematic examination of clinical notes found that 75% had previously reported a history of childhood sexual abuse. These women were more likely to self-harm, and in specific ways that may reflect their past experiences. Despite this, treatment within a dialectical behaviour therapy-informed therapeutic community leads to relatively greater clinical gains than for those without a reported sexual abuse trauma history. Notably, greater behavioural and self-reported distress and dissociation were not found to predict poor clinical outcome.

Declaration of interest

None.

Copyright and usage

© The Royal College of Psychiatrists 2015. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Non-Commercial, No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND) licence.

Within psychiatry, the familiar constellation of difficulty managing emotions and interpersonal relationships, together with an impaired sense of self, have been variously considered a problem of emotional dysregulation,1 of complex post-traumatic stress,2 of disorganised attachment and mentalising capacity3 and of borderline personality disorder.4 In addition, studies have found an association between borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma,5 and that childhood sexual abuse is predictive of cluster B personality disorders across cultures.6

The effective treatment of borderline personality disorder has proved challenging. Psychotherapeutic approaches have included the therapeutic community,7 and more recently, dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT).1 A review of psychological therapies for borderline personality disorder identified 28 studies, with only DBT having a sufficient number of studies to permit meta-analysis.8 Very large effects were found for reducing suicidal behaviour and associated depression and anxiety, a large effect for reducing anger and moderate effects for reducing parasuicidality and improving overall mental health status. There has been little research into the relationship between trauma history and the efficacy of DBT for people with borderline personality disorder, and a suggestion that there may generally be a poor clinical outcome for those with a combined borderline personality disorder and childhood sexual abuse history.9

Consequently, the primary objective of this study was to examine the relationship between treatment outcome and reported childhood abuse history in women with borderline personality disorder. A secondary objective was the exploration of their patterns of self-harm behaviours. Variables included the nature and severity of self-injurious behaviours, reported adverse developmental experiences and measures of psychological distress and dissociation before and after treatment.

Method

The sample consisted of 214 consecutive referrals between 2000 and 2012, referred with sufficiently severe borderline personality disorder to warrant admission to a UK national specialist personality disorder service for up to 12 months. Of these, 213 were state-funded tertiary referrals and 159 completed more than 60 days in therapy. Treatment of less than 60 days was considered unlikely to be beneficial with this population as this would prohibit a full cycle of DBT modules. All participants were female, predominantly White British (83%), a mean age of 32 years (s.d.=10, range 18–59 years) with a clinical diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Although residential, all patients were treated informally within an open unit. DBT was undertaken within a UK accredited therapeutic community.

Participants provided data via a number of validated clinical outcome measures and a systematic case note review. A self-harm taxonomy consisting of 10 forms of self-injurious behaviour was constructed following a review of the literature: cutting, pathological cleaning, inhalation of noxious substances, injecting noxious substances (e.g. cleaning fluid and misuse of insulin), swallowing (e.g. sharps and overdose of medication), abnormal eating behaviour, force (e.g. belting, whipping and head banging), airway restriction (e.g. hanging and ligatures), electrocution/burns and harm directed at organs or body orifices (e.g. placing sharp objects in genitals). Data are collapsed into two groups representing the presence and the absence of reported childhood sexual abuse. Participant self-report measures included the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE-OM),10 and the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-II)11 completed pre-treatment and post-treatment on discharge.

Results

Of patients with borderline personality disorder engaging in more than 60 days of treatment within a residential DBT-informed therapeutic community, 75% had a documented history of childhood sexual abuse (childhood sexual abuse, n=119; no report of childhood sexual abuse, n=40). There were no significant differences between these two groups in terms of age (childhood sexual abuse, M=33.75, s.d.=10.49; no childhood sexual abuse, M=28.5, s.d.=8.98; t=2.85, P=0.091), or length of admission for treatment (childhood sexual abuse, range 60–483 days; no childhood sexual abuse, range 65–483 days; t=0.774, P=0.329).

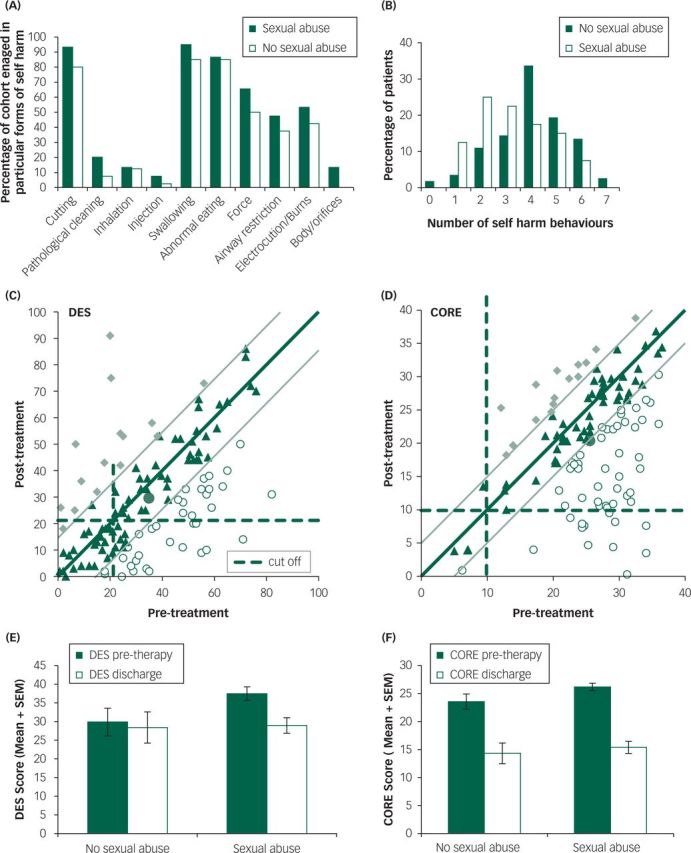

All patients engaged in at least one form of self-harm (Fig. 1A), with those reporting a childhood sexual abuse history showing a more severe profile (Fig. 1B). Analysis using the chi-square test (Fisher’s exact test was used owing to unequal group sizes, 1-tailed) revealed a significantly larger proportion of patients reporting childhood sexual abuse engaged in self-cutting (χ2=5.831, P=0.022), and swallowing (χ2=4.254, P=0.049). Only those reporting a childhood sexual abuse history directed self-harm behaviours at their body orifices or organs (χ2=3.756, P=0.040); however, this form of self-harm was only observed in a small percentage of patients (n=16, 10%). There was no difference in the number of people who engaged in other categories of self-harm (P>0.05).

Fig. 1. (A) Percentage of patients with borderline personality disorder showing particular forms of self-harm behaviours as reported in case notes. (B) Number of self-harm behaviours in patients with and without a reported history of childhood sexual abuse. (C–D) DES and CORE Jacobson plots. Circles, reliable change; triangles, no change; diamonds, deteriorated; green circle, average client score pre- and post-treatment; black line, line of no change. Within tramlines, no reliable change. (E) Patients who reported a history of sexual abuse had significantly higher levels of dissociation (DES-II) pre-therapy; this significantly reduced post-therapy. (F) Levels of psychological distress (CORE) significantly reduced in both groups following therapy.

Examination of psychometric data, presented as Jacobson plots (Fig. 1C and 1D), revealed that the majority of patients reported a reduction in CORE and DES scores post-therapy; patients experienced reliable and statistically significant change more often on CORE than on the DES. It can be seen, however, that a greater number of patients had low pre-therapy DES scores and therefore were less likely to experience reductions in a potentially sub-clinical problem. There were a small number of outliers who reported a reliable and significant deterioration in DES score, contributing to the greater variability in levels of dissociation post-therapy. The overall mean for psychological distress (CORE) represents a reliable clinical improvement post-therapy.

The data (Fig. 1E and 1F) further revealed that patients who reported a childhood sexual abuse history had significantly higher pre-therapy dissociation (DES) (Mann–Whitney test, Z=2.012, P=0.044, effect size r=0.167). There was no significant difference between groups in levels of psychological distress pre-therapy (CORE; Z=1.721, P=0.085). Following treatment, DES scores significantly reduced in patients reporting childhood sexual abuse but not in patients who did not report childhood sexual abuse (DES, Wilcoxon, childhood sexual abuse, Z=3.586, P=0.001, effect size r=0.376; no childhood sexual abuse, Z=0.227, P=0.820). In contrast, both patient groups showed significant reductions in CORE scores following therapy (childhood sexual abuse, Z=4.770, P=0.001, effect size r=0.497; no childhood sexual abuse, Z=2.909, P=0.001, effect size r=0.303).

Discussion

In accord with previous findings,5 women with borderline personality disorder of sufficient severity to warrant state-funded referral to a specialist residential personality disorder service (2000–2012) were three times more likely to have a documented history of reported childhood sexual abuse. Self-harm in all forms was more frequent in women who reported childhood sexual abuse. One form of self-harm was found only in the childhood sexual abuse group, albeit at a low frequency; women without a childhood sexual abuse history did not direct their self-injury towards their genitalia and breasts.

A medium effect size was found for post-treatment improvement in psychological distress among the childhood sexual abuse group, and a small-to-medium effect size for post-treatment improvement in dissociation. Treatment was also effective for those not reporting childhood sexual abuse albeit to a lesser degree; a small effect was found for distress. There was little change in dissociation, however, likely due to low pre-treatment dissociation in those not reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse.

While these results support the clinical effectiveness of a DBT-informed therapeutic community, unlike other studies,9 there was a relatively greater improvement in the more symptomatic childhood sexual abuse group on all measures. It is possible that DBT delivered within an informal (non-detained) residential therapeutic community offers a treatment advantage for this population. The therapeutic community may offer a contained opportunity to consolidate DBT skills and further address the interpersonal difficulties that commonly follow adverse childhood experiences within relationships, for example, fear of trust and friendship. This may then potentially facilitate the normal distress-reducing benefit of reciprocal relationships.

Given the centrality of hope to recovery in mental health, these results may have clinical benefit in imparting therapeutic optimism in patients and clinicians alike as high levels of behavioural and self-reported distress and dissociation did not predict poor clinical outcome.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jenna Kirtley, Adele Hurst, Megan Shakeshaff, Michelle Potts and Susanna Ward for their systematic review of archive data. We are also grateful to Jo Clarke for facilitating the collaborative research group.

References

- 1.Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herman J. Trauma and Recovery. New York: Basic Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonagy P. Attachment and borderline personality disorder. J Am Psychoanal Ass 2000; 48: 1129–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: 5th edition (DSM-5) APA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanarini MC, Wedig MM. Childhood adversity and the development of borderline personality disorder In Handbook of Borderline Personality Disorder in Children and Adolescents ( Sharp C. & Tackett L.): 265–276. Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang T, Chow A, Wang L, Dai Y, Xiao Z. Role of childhood traumatic experience in personality disorders in China. Comprehensive Psych 2012; 53: 829–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearce S, Pickard E. How therapeutic communities work. Int J Soc Psych 2013; 59:636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoffers J, Völlm B, Rücker G, Timmer A, Huband N, Lieb K. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder.Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 8: 1–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnicot K, Priebe S. Post-traumatic stress disorder and the outcome of dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder. Personal Ment Health 2013; 7: 181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans C, Connell J, Barkham M, Margison F, McGrath G, Mellor-Clark J, Audio K. Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180: 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson E, Putnam F. Dissociative Experiences Scale-II. Chicago, 2001. [Google Scholar]