Abstract

Context:

D. macrostachyum is an epiphytic orchid abundant in Southern India and is reported for pain relief in folklore.

Aims:

The objective of the present study was to determine in vitro free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory activity of D. macrostachyum and to perform LCMS based metabolic profiling of the plant.

Settings and Design:

Sequential stem and leaf extracts were assessed for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity by in vitro methods.

Materials and Methods:

The antioxidant activity determined by assays based on the decolourization of the radical monocation of DPPH, ABTS and reducing power. Total amount of phenolics for quantitative analysis of antioxidative components was estimated. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity was evaluated using protein denaturation assay, membrane stabilization assay and proteinase inhibitory activity. Methanolic extract of plant was subjected to LCMS.

Results:

The stem ethanolic extracts exhibited significant IC50 value of 10.21, 31.54 and 142.97 μg/ml respectively for DPPH, ABTS radical scavenging and reducing power activity. The ethanol and water extract was highly effective as albumin denaturation inhibitors (IC50 = 114.13 and 135.818 μg/ml respectively) and proteinase inhibitors (IC50 = 72.49 and 129.681 μg/ml respectively). Membrane stabilization was also noticeably inhibited by the stem ethanolic extract among other extracts (IC50 = 89.33 μg/ml) but comparatively lower to aspirin standard (IC50 = 83.926 μg/ml). The highest total phenol content was exhibited by ethanolic stem and leaf extracts respectively at 20 and 16 mg of gallic acid equivalents of dry extract. On LCMS analysis 20 constituents were identified and it included chemotaxonomic marker for Dendrobium species.

Conclusions:

The results showed a relatively high concentration of phenolics, high scavenger activity and high anti-inflammatory activity of the stem extract compared to the leaf extract. The results indicate that the plant can be a potential source of bioactive compounds.

KEYWORDS: Anti-inflammatoryactivity, antioxidant activity, dendrobium, Dendrobium macrostachyum, general unknown screening, in vitro bioassays, marathilotti, orchidaceae, radam, reducing power, total phenol

INTRODUCTION

The genus Dendrobium with 1190 species is one of the most important genera in the orchid family. Orchidaceae, as being the source of wide variety of biologically active compounds are used extensively as crude material or pure compounds for treating various disease conditions.[1] Among them, Dendrobium macrostachyum Lindl (Common name: Radam/Marathilotti) is one of the widespread Dendrobium orchid species found in the plains of Southern India. It is an epiphytic herb, stem tufted, leaves membranous and deciduous during flowering season with small green flowers and narrow petals.[2,3,4] Presence of alkaloids, leaf flavonoids, sterols, glycosides, tannins and phenols were reported in a study.[4] A detailed study on ethylacetate fraction of ethanolic stem extract was found to possess good anti-lipoxygenase activity in-vitro.[5] Traditional use of tender tip juice for earache is reported.[6] Rural folk of Northern Andaman islands use whole plant to relieve pain.[7]

The utilization of liquid chromatography coupled to single (LC – MS) and tandem (LC – MS/MS) mass spectrometry has grown rapidly and is now widely recognized as powerful tool for a comprehensive General Unknown Screening (GUS) of organic molecules in a multiple component mixture.[8] In the present investigation, an effort is made to phytochemically profile Dendrobium macrostachyum Lindl. using these advanced techniques. The determination of these characters along with their in-vitro anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity screening will help establish the pharmaceutical values of this pharmacologically unscreened plant in future studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and authentication of plant

The plant materials collected at the flowering state in June from Melattur (North Kerala, India), was identified and a voucher specimen (5/23/2011 – 12/Tech. 785) was deposited in the Herbarium, Southern Regional Centre, Botanical Survey of India.

Preparation of extract and bioactivity studies

The fresh plant materials were collected, washed, stems and leaves separated, blended into small fragments and shade dried. The dried plant materials were disintegrated using mixture grinder, powdered well and then powder was passed through sieve No: 60 and stored. Dried ground stem and leaves (50 g) were extracted in Soxhlet extractor sequentially in 150 ml using increasing polarity (Petroleum Ether, Ethanol, Methanol, Water) to give eight extracts of the same nature (Solid). The extract yields were noted and tabulated [Table 1]. Total phenolic contents (TPC) were determined spectrophotometrically using Folin – Ciocalteu reagent and results were expressed as (+) milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE).[9]

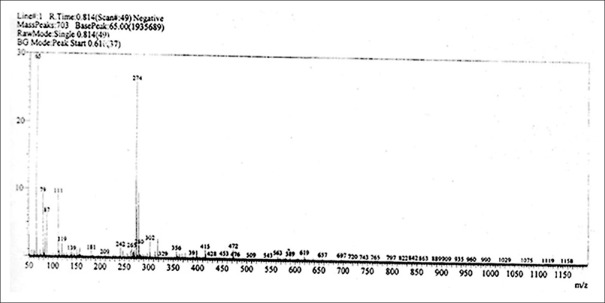

Table 1.

Total phenolic content and yields of Dendrobium macrostachyum extracts

Antioxidant activity was determined by spectrophotometric methods based on the reduction of an ethanol solution of DPPH[10] and by measuring ABTS+ radical cation formation induced by metmyoglobin and hydrogen peroxide.[11] We also used FRAP assay which uses anti-oxidants as reductants in a redox linked colorimetric method to test the total antioxidant power directly.[12]

In-vitro anti-inflammatory activity was evaluated using inhibition of protein denaturation which was calculated with bovine albumin fraction after heating (37°C for 20 min and then at 57°C for 20 min) and read at 600 nm.[13] Red blood cell membrane stabilization method (RBC method)[14] and anti-proteinase activity[15] at different concentrations, was also used for the confirmation of anti-inflammatory activity in vitro.

Ascorbic acid was used as positive control for free radical scavenging and antioxidant activities whereas aspirin for anti-inflammatory activity studies. The tests were done in triplicates for each sample and the means were used to determine the percentage radical scavenging activity by (A – B/A) ×100, where A is the activity without test material and B is the activity with test material. The activities studied were expressed as IC50.

Sample and Buffer preparation for LC – MS

Extract was reconstituted in 1 ml of a 10% methanol solution. Standards were prepared by spiking stock solutions of drug mixtures to make concentrations ranging from 0.500 to 5 mg/ml, resulting in a set of standards with the following concentrations: 0.500, 1.000, 1.500, 2.000 and 5.000 mg/ml. A buffer (pH 2.2) was prepared with a 20 mmol/l K2 HPO4 solution.

Chromatographic and mass spectral conditions

Extract was subjected to chromatographic separation on Phenomenex Reverse phase 18 column (dimension 25 cm × 2.5 cm) and operated at a column temperature of 25°C with a flow rate of 2 ml/min. Injection volume was 10 µl. Electronic spray ionization (ESI) mode was used with m/z range of 50–1000 for negative and 50–980 for positive. Class VP integrated software was used and identification of isolated compounds was based on the comparison of the mass spectral data with METWIN 2.0.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The amounts of TPC were found to vary over a wide range (3 to 20 mg/g) with it being higher in stem extract as compared to leaf extract [Table 1]. The phenolic substances are known to possess the ability to reduce oxidative damage and acts as antioxidants.[16]

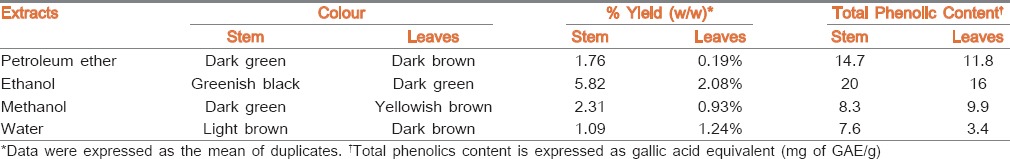

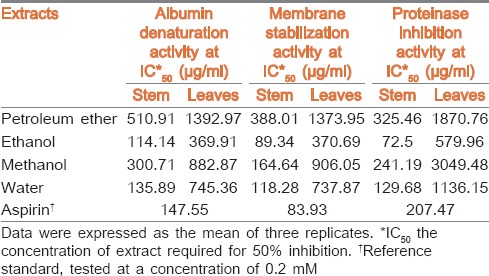

The results exhibited a relatively high concentration of antioxidants, high scavenger activity and high anti-inflammatory activity in stem compared to leaves. On comparing various stem extracts, ethanolic extract was a more effective radical scavenger and anti-inflammatory as compared to petroleum ether, methanol, water extracts and positive standards (ascorbic acid and aspirin respectively). IC50 (µg/ml) values of the scavenging and anti-inflammatory activity were determined from the concentration–effect regression lines is tabulated in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Antioxidant activities of Dendrobium macrostachyum extracts

Table 3.

Anti-inflammatory activity of Dendrobium macrostachyum extracts at IC50

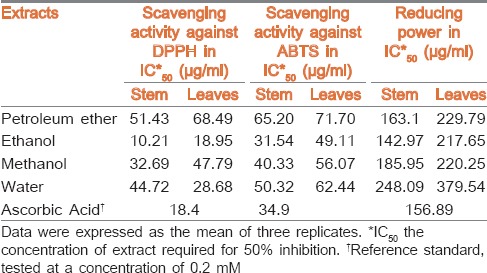

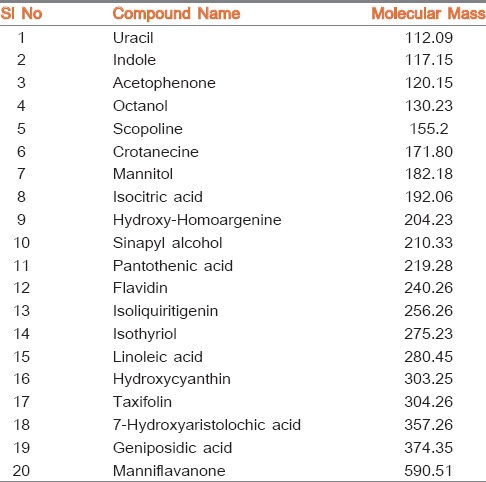

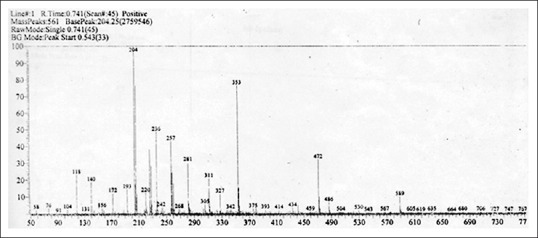

GUS analysis for exploring metabolites present in Dendrobium macrostachyum Lindl with LC – MS identified 20 compounds including chemotaxonomic marker Flavidin (a phenantherene class of compound), of the genus Dendrobium. The compounds are listed below in Table 4 with their molecular mass. Liquid Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry (LC – MS) is proved to be a useful technique for plant metabolite profiling which allows the quantification of a large variety of plant metabolites in a single chromatogram.[17] The LCMS spectra of both positive mode and negative mode are included as Figures 1 and 2 respectively. Identification is done with the aid of Computer assisted evaluation of the resulting data by searching against the spectral library. Some of the identified compounds are reported to have great pharmacological importance, while some compounds are novel and yet to be studied.

Table 4.

Identified compounds from LC-MS Spectrum

Figure 1.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry spectrum (positive mode)

Figure 2.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry spectrum (negative mode)

Present investigation constitutes the first screening of Dendrobium macrostachyum Lindl and the resultant scavenging and anti-inflammatory activities gives insight to the strong presence of bioactive constituents. Recent research centers on various strategies to protect crucial tissues and organs against oxidative damage induced by free radicals. Hence, possible identification and isolation of biologically active compounds will be valuable.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that the ethanolic stem extract of Dendrobium macrostachyum Lindl possesses high phenolic content, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity that might be helpful in preventing or slowing the progress of various oxidative stress related diseases. Metabolic profiling provided an evidence of the presence of promising compounds for the abovesaid activity. Further investigation on the isolation, identification and mode of action may lead to chemical entities with potential for clinical use.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Uwin life sciences for performing the LCMS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bulpitt CJ, Li Y, Bulpitt PF, Wang J. The use of orchids in Chinese medicine. J R Soc Med. 2007;100:558–63. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.100.12.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre S. The strange case of Dendrobium aphyllum. Orchid Rev. 2011;119:104–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham A, Vatsala P. Introduction to Orchids with Illustration and Descriptions of 150 South Indian Orchids. 1st ed. Trivandrum: Tropical Botanical Garden and Research Institute Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nimisha PS, Hiranmai YR. Proximate and physicochemical analysis of Dendrobium macrostachyum Lindl. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2011;4:385–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimisha PS, Hiranmai YR. Anti-lipoxygenase (LOX) activity of Dendrobium macrostachyum Lindl. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2012;3:601–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hossain MM. Therapeutic orchids: Traditional uses and recent advances – An overview. Fitoterapia. 2011;82:102–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad PR, Reddy CS, Raza SH, Dutt CB. Folklore medicinal plants of North Andaman Islands, India. Fitoterapia. 2008;79:458–64. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauvage FL, Picard N, Saint-Marcoux F, Gaulier JM, Lachâtre G, Marquet P. General unknown screening procedure for the characterization of human drug metabolites in forensic toxicology: Applications and constraints. J Sep Sci. 2009;32:3074–83. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singelton VR, Orthifer R, Lamuela-Raventos RM. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piao XL, Park IH, Baek SH, Kim HY, Park MK, Park JH. Antioxidative activity of furanocoumarins isolated from Angelicae dahuricae. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93:243–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathew S, Abraham TE. In vitro antioxidant activity and scavenging effects of Cinnamomum verum leaf extract assayed by different methodologies. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006;44:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selvakumar K, Madhan R, Srinivasan G, Baskar V. Antioxidant assays in pharmacological research. Asian J Pharm Technol. 2011;1:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizushima Y, Kobayashi M. Interaction of anti-inflammatory drugs with serum proteins, especially with some biologically active proteins. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1968;20:169–73. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1968.tb09718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azeem AK, Dilip C, Prasanth SS, Junise V, Shahima H. Antiinflammatory activity of the glandular extracts of Thunnu salalunga. Asia Pac J Med. 2010;3:412–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oyedepo OO, Femurewa AJ. Anti-protease and membrane stabilizing activities of extracts of Fagra zanthoxiloides, Olax subscorpioides and Tetrapleura tetraptera. Int J Pharmacongn. 1995;33:65–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halliwell B. Antioxidants and human disease: A general introduction. Nutr Rev. 1997;55:S44–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb06100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payal SS, Tribhuwan S, Rekha V, Jayabaskaran C. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry based profile of bioactive compounds of Cucumiscallosus. Eur J Exp Biol. 2013;3:316–26. [Google Scholar]