Abstract

In evolving to an obligate intracellular niche, Chlamydia has streamlined its genome by eliminating superfluous genes as it relies on the host cell for a variety of nutritional needs like amino acids. However, Chlamydia can experience amino acid starvation when the human host cell in which the bacteria reside is exposed to interferon gamma (IFN-γ), which leads to a tryptophan (Trp)-limiting environment via induction of the enzyme indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). The stringent response is used to respond to amino acid starvation in most bacteria but is missing from Chlamydia. Thus, how Chlamydia, a Trp auxotroph, responds to Trp starvation in the absence of a stringent response is an intriguing question. We previously observed that C. pneumoniae responds to this stress by globally increasing transcription while globally decreasing translation, an unusual response. Here, we sought to understand this and hypothesized that the Trp codon content of a given gene would determine its transcription level. We quantified transcripts from C. pneumoniae genes that were either rich or poor in Trp codons and found that Trp codon-rich transcripts were increased, whereas those that lacked Trp codons were unchanged or even decreased. There were exceptions, and these involved operons or large genes with multiple Trp codons: downstream transcripts were less abundant after Trp codon-rich sequences. These data suggest that ribosome stalling on Trp codons causes a negative polar effect on downstream sequences. Finally, reassessing previous C. pneumoniae microarray data based on codon content, we found that upregulated transcripts were enriched in Trp codons, thus supporting our hypothesis.

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia is an obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen that causes a range of illnesses in humans and animals (1–4). It alternates between functionally and morphologically distinct forms during its developmental cycle (see reference 5 for review). The elementary body (EB) mediates attachment and internalization into a susceptible host cell, whereas the reticulate body (RB) grows and divides within a membrane-bound pathogen-specified parasitic organelle termed an inclusion (6). In evolving to obligate intracellular parasitism, Chlamydia has streamlined its genome by eliminating superfluous pathways and genes (7). Conversely, if Chlamydia has maintained a set of genes, then it is likely important for the bacterium.

There are two primary species of Chlamydia that cause significant disease in humans: C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Many chlamydial infections are often unrecognized and asymptomatic, and failure to treat these infections can lead to chronic sequelae. For C. trachomatis, these sequelae can include pelvic inflammatory disease, tubal factor infertility, and reactive arthritis (8, 9). C. pneumoniae has been associated with a number of chronic conditions, including atherosclerosis and adult-onset asthma among others (10, 11). One possible explanation for asymptomatic chlamydial infections may be due to the ability of the organism to enter a nonproductive growth state referred to as persistence.

Chlamydial persistence is a culture-negative but viable growth state characterized by a cessation of cell division and aberrant bacterial morphology (12, 13). Persistence in vitro can be induced in cell culture by a variety of methods, including interferon gamma (IFN-γ) treatment of infected human host cells (14), iron starvation via chelation (15, 16), and amino acid starvation (17–19). Of these, IFN-γ-mediated persistence is the most studied and likely the most relevant to in vivo infections (20). The means by which IFN-γ induces persistence in Chlamydia is well characterized (14, 21, 22). IFN-γ induces indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression in human cells, and IDO cleaves tryptophan (Trp [W]) (23). C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae are Trp auxotrophs and acquire this essential amino acid from the host cell via the free amino acid pools in the cytosol or via uptake of lysosomal degradation products (24). Once starved of Trp, these pathogens stop dividing and become aberrantly enlarged, and their progression through the developmental cycle is blocked. However, removal of IFN-γ from the culture medium will lead to reactivation of productive growth with continued progress through the developmental cycle (25). IDO is the key mediator of the IFN-γ effect in human epithelial cells because (i) chlamydiae grown in IDO mutant cells treated with IFN-γ grow normally, (ii) flooding the culture medium with high levels of trp will allow for normal growth even in the presence of IFN-γ, and (iii) treating cells with an IDO inhibitor in the presence of IFN-γ also allows for normal growth (26–28).

Many laboratories, including our own, have investigated the transcriptional and proteomic changes that lead to IFN-γ-mediated persistence in Chlamydia (29–40). Unfortunately, these studies incorporated two methodological errors: incorrect normalization methods and inappropriate comparisons between samples. The former methodological error was, in retrospect, not surprising given that most bacterial transcriptional studies use so-called “housekeeping” genes to normalize transcript data, with the assumption that these genes accurately reflect bacterial numbers (and, therefore, growth state). However, as Chlamydia is a developmentally regulated bacterium that transitions between very different functional forms, there is no bona fide housekeeping gene that is expressed consistently during all developmental stages (41). Rather, the template for transcription—that is the chromosome—is the best means to normalize chlamydial transcript data (41, 42). The latter methodological error stemmed from the comparison of a population of “RBs differentiating to EBs” to the persistent forms (i.e., comparing equivalent time points postinfection of samples that are fundamentally very different). A more useful comparison is to perform longitudinal analyses within the same sample set to determine what happens as the RB transitions to a persistent form. Consequently, most of the previously published transcriptional studies are difficult to interpret, and all assume a specific “regulon” is induced by Chlamydia in response to Trp limitation.

In 2006, we investigated C. pneumoniae transcription via gene chip microarray during IFN-γ-mediated persistence and used genomic DNA (gDNA) normalization of our transcript data (42). We found that, contrary to expectations that a specific regulon would be induced, chlamydial transcription was globally increased during IFN-γ-mediated persistence, whereas translation was globally decreased. The latter finding is not surprising given that Trp is necessary for the translation of most proteins (∼80% in Chlamydia, with an average Trp content per protein of 0.96% for C. pneumoniae). We hypothesized that one explanation for the unusual observation of increased transcription may be that Chlamydia increases the transcription of genes that contain Trp codons in a futile attempt to make the protein. To test this, we measured the transcript levels of a subset of C. pneumoniae genes that were either rich or poor in Trp codons. Our results indicate that transcription of Trp codon-rich genes is generally increased, whereas transcription of Trp-free or Trp codon-poor genes is generally decreased or unchanged during IFN-γ-mediated Trp starvation. Some exceptions were noted in regard to operons and large genes, but a closer analysis revealed that these exceptions could be rationalized based on the overall Trp codon content of the operon/gene where upstream Trp codons lead to destabilization of downstream transcripts. Finally, we reexamined our earlier microarray data as a function of codon content and found that the most “upregulated” transcripts were significantly enriched in Trp codons, whereas the “downregulated” transcripts showed Trp codon levels that were average for the proteome. Additionally, the most downregulated transcripts corresponded to the largest genes, in keeping with a general defect in translation leading to transcript destabilization. These findings are in keeping with a model in which ribosome stalling on Trp codons feeds back to increase the transcription of the given gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and cell culture.

Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39 EBs were harvested from infected HEp-2 cell cultures at 35°C with 5% CO2, and their titers were determined for infectivity by determining inclusion-forming units (IFU) on fresh cell monolayers. The human epithelial cell line HEp-2 was routinely cultivated at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) containing GlutaMAX, glucose, HEPES, and sodium bicarbonate (Gibco-Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma). The HEp-2 cells were a kind gift from H. Caldwell (Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID). Recombinant human interferon gamma (IFN-γ) was purchased from Cell Sciences (Canton, MA) and resuspended to 100 μg ml−1 in 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) diluted in water. Aliquots were frozen at −80°C and used once only to avoid freeze-thawing. IFN-γ was titrated for its effect to induce persistence without killing and in our experiments was used at 2 ng ml−1 and added at the time of infection.

Nucleic acid extraction and RT-qPCR.

For transcript analyses, HEp-2 cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 106 per well and infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 with C. pneumoniae AR39. In some wells, cells were plated and infected on coverslips to monitor the infection and progression to persistence (see “Immunofluorescence analysis”). Assays to quantify the indicated transcripts were performed essentially as described previously (41, 42). Briefly, total RNA was collected from infected cells at the indicated times using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Thermo) and rigorously treated with Turbo DNAfree (Ambion, Life Technologies) to remove contaminating DNA, according to the manufacturer's guidelines. One microgram of DNA-free RNA was reverse transcribed with random nonamers (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RT reaction mixtures were diluted 10-fold with water and aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Equal volumes of cDNA were used in 25-μl quantitative PCRs (qPCRs) with SYBR green (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) and measured on an ABI 7300 system (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) using the standard amplification cycle with a melting curve analysis. Results were compared to a standard curve generated against purified C. pneumoniae genomic DNA. Duplicate DNA samples were collected from the same experiment using the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen). Chlamydial genomes were quantified from equal amounts of total DNA by qPCR using the euo primer set as described above and used to normalize transcript data as described previously (41, 42). RT-qPCR results were corrected for efficiency (typically above 90% with r2 values above 0.999). Primer sequences are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material and were designed using the PrimerQuest tool (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) based on the C. pneumoniae CWL029 sequence available from the STD sequence database (http://stdgen.northwestern.edu). Results were graphed using GraphPad Prism 6 for Mac OS X (version 6.0f; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Student's t test was used for determination of significance of differences between the 48-h-postinfection (hpi) IFN-γ-treated sample and the 24-hpi sample. Spearman's rank correlation analysis was performed for the data in Table 1 to determine the significance of fold change as a function of Trp codon content.

TABLE 1.

| Gene name | Function | No. of Trp codons | Fold change in transcript in IFN-γ-treated cells from 24 to 48 hpia |

|---|---|---|---|

| mreB | Cell division | 0 | 0.63 ± 0.26 |

| rodZ | Cell division | 5 | 5.91 ± 0.47 |

| nusA | Transcription | 0 | 0.75 ± 0.19 |

| nusG | Transcription | 4 | 2.34 ± 0.47 |

| dksA | Transcription | 0 | 0.70 ± 0.34 |

| rho | Transcription | 0 | 1.11 ± 0.03 |

| obg | Translation | 2 | 8.57 ± 3.29 |

| ubiA | Metabolism | 5 | 7.90 ± 1.90 |

| groEL_1 | Chaperone | 0 | 0.16 ± 0.12 |

| groEL_2 | Chaperone | 2 | 1.96 ± 0.29 |

| groEL_3 | Chaperone | 1 | 1.74 ± 0.41 |

| clpP_1 | Protein degradation | 3 | 1.65 ± 0.05 |

| clpP_2 | Protein degradation | 0 | 0.35 ± 0.09 |

| rsbV_1 | Transcription | 0 | 0.95 ± 0.22 |

| rsbV_2 | Transcription | 0 | 1.23 ± 0.37 |

P = 0.0001 and r = 0.8560 by Spearman rank correlation analysis for fold change versus Trp content.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

For culture on coverslips, the cells were fixed in methanol at 48 h postinfection and stained with a mouse primary antibody targeting the C. pneumoniae major outer membrane protein (MOMP) GZD1E8, a kind gift from H. Caldwell) and a goat anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies). Images were collected on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope. Images were processed equally for brightness and contrast in Adobe Photoshop.

Western blotting.

HEp-2 cells were infected with C. pneumoniae and treated or not with IFN-γ as described above. At 24 or 48 hpi, cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) with 1% FBS, 150 μM clastolactacystin (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), and 1× HALT protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, ThermoFisher). Protein concentrations were determined using the EZQ protein concentration kit (Molecular Probes, ThermoFisher). Samples were equilibrated by taking known protein concentrations and diluting them based on genome equivalents, using 24-hpi samples as the baseline. Samples were resolved by SDS–12% PAGE and transferred for 60 min at constant 0.04 A using the Trans-Blot SD semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Western blots were developed using a mouse primary antibody against chlamydial Hsp60 (a kind gift from Rick Morrison, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) and goat anti-mouse IRDye-800CW secondary antibody (LiCor, Lincoln, NE). The Western blot was imaged using the LiCor Odyssey CLx and subsequently processed, including densitometric analysis, with LiCor Image Studio (version 5.2.5).

Microarray analysis.

The C. pneumoniae microarray data set from Ouellette et al. (42), a measure of transcription at 24 and 48 h postinfection in the presence and absence of IFN-γ, was analyzed based on codon content by merging the array data into an in-house-generated file listing the amino acid content for each open reading frame (ORF) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Data were then sorted based on fold change in transcript levels from 24 to 48 hpi during the different treatment conditions. The individual codon content for those genes that were at least 2-fold increased during IFN-γ, with the exception of late genes (described below), were then averaged. The same analysis was performed for those genes that were 2-fold decreased. The data file also included protein length, which was used to calculate the average size of the gene products from the up- and downregulated data sets. Spearman rank correlation analysis was performed on the data sets to determine the correlation between amino acid content and fold change in transcription in GraphPad Prism 6.

RESULTS

Chlamydial transcriptional responses are highly reproducible.

Our prior experiments assessing chlamydial transcription during IFN-γ-mediated persistence focused primarily on C. pneumoniae as a model system, although we measured responses of C. trachomatis as well (42). Here, we decided to continue using C. pneumoniae with the rationale that its longer developmental cycle would lead to more reproducible results in response to IFN-γ added at the time of infection, as opposed to C. trachomatis, where we typically have to add IFN-γ prior to infection to ensure that tryptophan (Trp) pools are sufficiently diminished (43). We previously observed that it takes approximately 24 h for IFN-γ-activated human epithelial cells to deplete their Trp pools, and this is consistent with the findings of others (44, 45).

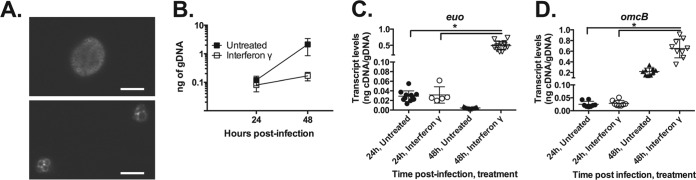

Chlamydial transcription can be broadly categorized based on the developmental cycle (46). Early genes are transcribed during EB-to-RB differentiation. Mid-cycle genes are transcribed during RB growth and division. Late genes are transcribed during RB-to-EB differentiation. We initiated these studies by measuring transcript levels of two genes: euo, an early gene, and omcB, a late gene (47–49). We and others have observed that euo transcription is highly elevated during IFN-γ-mediated persistence (20, 35, 42). Unusually, we previously observed that late gene transcription is also activated during IFN-γ-mediated persistence (42), likely owing to the inability to translate a negative regulator of late gene transcription. Importantly, late gene transcription is not accompanied by either late proteins or the production of EBs (42). We collected RNA and DNA samples from seven separate experiments and analyzed transcripts from multiple technical and/or biological replicates to assess the reproducibility of chlamydial transcriptional responses. We assayed two time points: 24 h postinfection (hpi), corresponding to peak mid-cycle/RB growth, and 48 hpi, a late time when RBs are converting to EBs. Monitoring chlamydial growth and morphology in IFN-γ-treated cells at 48 hpi, we observed typically aberrant forms in smaller inclusions (Fig. 1A) and noted that DNA replication effectively ceases (Fig. 1B) (42).

FIG 1.

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) induces a highly reproducible persistent phenotype in C. pneumoniae. (A) Characteristic immunofluorescent images of C. pneumoniae cells from untreated or IFN-γ-treated cultures. HEp-2 cells were infected with C. pneumoniae and treated or not with IFN-γ. At 48 h postinfection, infected cells were fixed and stained for the major outer membrane protein. IFN-γ-induced persistence results in smaller inclusions containing aberrantly enlarged RB forms. (B) Quantification of C. pneumoniae genomic DNA (gDNA) by qPCR from untreated (solid symbols) and IFN-γ-treated (open symbols) cultures at 24 and 48 h postinfection. (C and D) Quantification of C. pneumoniae euo (C) and omcB (D) transcript levels from untreated and IFN-γ-treated cultures at 24 and 48 h postinfection. Individual data points (themselves averages from three measurements) are from all technical and biological replicates from all experiments (n = 7, except 24-hpi IFN-γ, where n = 4). *, P ≤ 0.05 for 48-hpi IFN-γ versus 24-hpi IFN-γ.

From our multiple sample measurements, we made several key observations. First, in keeping with its taking approximately 24 h to deplete Trp pools, there was no statistical difference in gene transcription or DNA replication in untreated or IFN-γ-treated C. pneumoniae cultures at 24 hpi (Fig. 1B to D; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The transcript levels within the IFN-γ-treated cultures at 24 hpi were statistically indistinguishable from, and within 1.5-fold of, those of the untreated sample for all transcripts we have measured (42) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and thus we use this cutoff to determine changes in transcription by RT-qPCR. Second, euo and omcB transcription is highly reproducibly elevated during IFN-γ treatment as previously observed (42). Whether comparing the raw transcript data (i.e., nanograms of cDNA/gDNA) across experiments or normalizing within each experiment to the 24-h value (i.e., fold change [data not shown]), both transcripts are significantly (P ≤ 0.05) and reproducibly increased (Fig. 1C and D). Thus, we conclude that the IFN-γ-mediated transcriptional changes in C. pneumoniae are reproducible across experiments when persistence is confirmed by other means (e.g., genomic DNA levels, aberrant morphology, etc.).

Chlamydial transcription during IFN-γ-mediated Trp limitation correlates with Trp codon content.

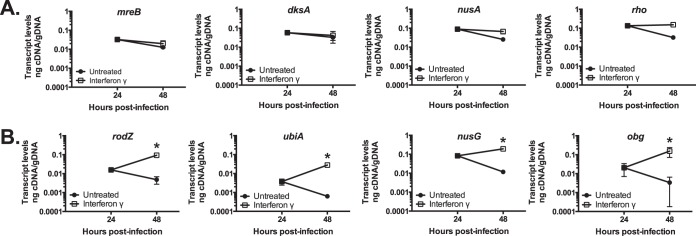

Interestingly, euo contains three Trp residues in C. pneumoniae (versus two in C. trachomatis), and its transcript levels are highly elevated during IFN-γ-mediated persistence. To begin testing our hypothesis that chlamydial transcription during IFN-γ-mediated Trp limitation is dependent on the Trp codon content of the gene being transcribed, we measured the transcript levels of eight genes, with various Trp codon contents, representing diverse functions from cell division (mreB and rodZ) (50, 51), to transcription (nusA, nusG, dksA, and rho), to translation (obg) (52), to metabolism (ubiA). MreB, DksA, NusA, and Rho contain no Trp. RodZ (5 Trp codons), NusG (4 Trp codons), UbiA (5 Trp codons), and Obg (2 Trp codons) contain various numbers of Trp codons. Consistent with our hypothesis, transcript levels for all genes lacking Trp codons were either unchanged or decreased and showed no statistically significant differences from the 24-hpi samples (Fig. 2A). Conversely, transcripts for those genes containing Trp codons were significantly (P ≤ 0.05) increased in IFN-γ-treated cells (Fig. 2B). The fold change in transcript levels between 24 and 48 hpi during IFN-γ-mediated persistence can be seen in Table 1. Overall, these data support the hypothesis.

FIG 2.

The tryptophan codon content of a gene influences its transcription in C. pneumoniae during IFN-γ-mediated persistence. Nucleic acid samples were collected from untreated (solid symbols) and IFN-γ-treated (open symbols) C. pneumoniae-infected HEp2 cells at 24 and 48 h postinfection. Transcript levels for the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to genomic DNA (nanograms of cDNA/gDNA). (A) Quantification of transcript levels for genes containing no Trp codons: mreB, dksA, nusA, and rho. (B) Quantification of transcript levels for genes containing various numbers of Trp (W) codons: rodZ (5 codons), ubiA (5 codons), nusG (4 codons), and obg (2 codons). Data are averages from at least 2 experiments with standard deviations displayed. *, P ≤ 0.05 for 48-hpi IFN-γ versus 24-hpi IFN-γ.

Paralogous genes are transcribed in a pattern correlated with Trp codon content.

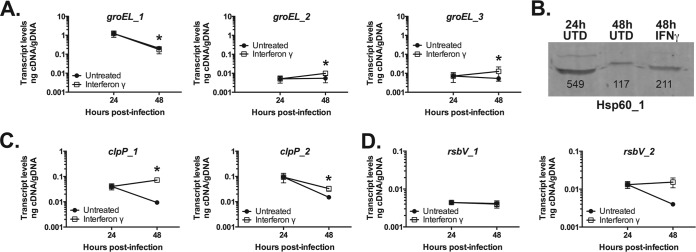

Chlamydia contains several sets of paralogous genes, and we reasoned that these genes may provide a unique opportunity to directly test our hypothesis of the effect of Trp codons on the transcription of a given gene during trp limitation. However, many of these paralogs have potential confounding factors, such as (i) the same or similar numbers of trp codons, (ii) transcriptional patterns reflecting different developmental stages (e.g., lcrH_1 and lcrH_2) (41), and (iii) positions within operons that might impact their transcript abundance (see “Exceptions” below). Therefore, we focused on two sets with different Trp codon contents in C. pneumoniae and one set in which neither gene encoded Trp codons: groEL_1 to -3, clpP_1 and -2, and rsbV_1 and -2. We then measured their transcript levels during IFN-γ-mediated Trp limitation. Each of these gene sets provided us with a unique opportunity to directly test our hypothesis. Additionally, each gene is located distally from its paralog and is thus regulated distinctly.

The groEL genes encode putative chaperones (53). Hsp60_1, encoded by groEL_1, contains no Trp residues, whereas Hsp60_2 and Hsp60_3 contain two Trp residues and one Trp residue, respectively. Interestingly, groEL_1 transcripts were decreased approximately 6-fold (0.16 ± 0.12) during Trp limitation and were statistically indistinguishable from the untreated sample at the 48-h time point. Conversely, groEL_2 (1.96 ± 0.29) and groEL_3 (1.74 ± 0.41) transcripts were increased by roughly 2-fold (Fig. 3A; Table 1). Of note, the groEL_2 primer set was located downstream of both Trp residues, whereas the groEL_3 primer set was located upstream of the single Trp residue (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Hsp60_1 protein was also decreased compared to the 24-h sample, as measured by Western blotting, with protein loading normalized for chlamydial genome content, and its levels were less than 2-fold different from those of the 48-h untreated sample (Fig. 3B). The decrease in Hsp60_1 is consistent with a decreased need for protein chaperone function when less translation is occurring (42).

FIG 3.

The presence of different tryptophan codon contents within paralogous genes in C. pneumoniae affects their transcription during IFN-γ-mediated tryptophan limitation. Nucleic acid samples were collected from untreated (solid symbols) and IFN-γ-treated (open symbols) C. pneumoniae-infected HEp2 cells at 24 and 48 h postinfection. Transcript levels for the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to genomic DNA (nanograms of cDNA/gDNA). (A) Quantification of transcript levels for groEL paralogues, where groEL_1 encodes 0 Trp codons, groEL_2 encodes 2 Trp codons, and groEL_3 encodes 1 Trp codon. (B) Western blot measurement of chlamydial Hsp60_1 (i.e., GroEL_1) from untreated and IFN-γ-treated C. pneumoniae-infected cultures. Protein loading was normalized for C. pneumoniae genomic DNA levels. Densitometry readings are displayed below the bands. (C) Quantification of transcript levels for clpP paralogues where clpP_1 encodes 3 Trp codons and clpP_2 encodes 0 Trp codons. (D) Quantification of transcript levels for rsbV paralogues where neither encodes Trp codons. All transcript data are the average from at least 2 experiments with standard deviations displayed. *, P ≤ 0.05 for 48-hpi IFN-γ versus 24-hpi IFN-γ.

The ClpP proteins function in the Clp protease system (54). ClpP_1 contains three Trp residues, whereas ClpP_2 contains none. As with the groEL paralogues, clpP_1 transcripts were significantly increased 1.65 ± 0.05-fold, whereas clpP_2 transcripts decreased 3-fold (0.35 ± 0.09) during IFN-γ treatment (Fig. 3C, Table 1). Given the role of ClpP in degradation of proteins, it is perhaps not surprising, given the decrease in translation we previously observed (42), that clpP_2 transcripts are decreased. Although not dramatically increased, the clpP_1 transcripts have the opposite profile consistent with the presence of Trp codons in the gene.

The RsbV proteins function within the Rsb anti-sigma factor signaling pathway to regulate, in Chlamydia, the function of the major housekeeping sigma factor (σ66) (55). Both RsbV_1 and RsbV_2 contain no Trp residues; transcripts for both were unchanged during Trp limitation (0.95 ± 0.22 and 1.23 ± 0.37, respectively) (Fig. 3D; Table 1). The transcription of these paralogous genes varied in a manner consistent with their Trp codon content and lends further support to the hypothesis.

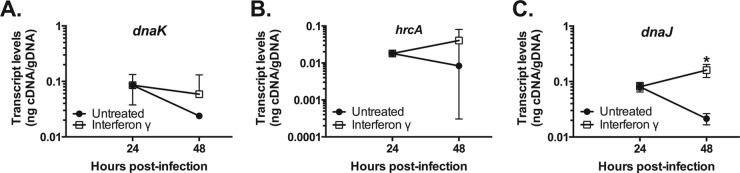

The heat shock regulon is maintained during IFN-γ-mediated persistence.

Our groEL_1 data were consistent with our prior observations (42) and prompted us to look more closely at the heat shock regulon, which serves an important chaperone function. We hypothesized that the global decrease in translation efficiency during IFN-γ-mediated persistence (42) would result in a decreased need for chaperone function. We also noted that, like groEL_1, the heat shock genes dnaK, dnaJ, and hrcA lack Trp codons: thus, we predicted that their transcript levels would be unchanged or decreased. Of note, dnaK is the terminal gene in the hrcA-grpE-dnaK operon, although it also encodes its own promoter (56, 57). As expected, dnaK followed the predicted pattern (0.2 ± 0.13) (Fig. 4A). However, hrcA transcripts increased, although with some variability (2.82 ± 2.15), which rendered the change statistically insignificant (Fig. 4B). HrcA is a negative regulator of the heat shock response that recognizes a consensus DNA-binding site called CIRCE: thus, an increase in hrcA transcripts (and presumably HrcA protein) that leads to downregulation of the other genes makes intuitive sense. The differences between dnaK and hrcA may reflect an unstable polycistronic transcript (e.g., see below) or differential regulation via the dnaK P2 promoter, which is not regulated by HrcA (57). dnaJ transcripts showed a consistent 2-fold increase (2.06 ± 0.16) (Fig. 4C). This increase of dnaJ transcripts is more difficult to rationalize and represents a potential exception to our overall hypothesis. It further suggests that dnaJ may not be regulated by HrcA, which is consistent with the lack of an identifiable CIRCE element upstream of dnaJ.

FIG 4.

Measurement of C. pneumoniae transcript levels for genes associated with the heat shock response during IFN-γ-mediated persistence. Nucleic acid samples were collected from untreated (solid symbols) and IFN-γ-treated (open symbols) C. pneumoniae-infected HEp2 cells at 24 and 48 h postinfection. Transcript levels for the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to genomic DNA (nanograms of cDNA/gDNA) for (A) dnaK, (B) hrcA, and (C) dnaJ. All transcript data are the average from at least 3 experiments with standard deviations displayed. *, P ≤ 0.05 for 48-hpi IFN-γ versus 24-hpi IFN-γ.

Exceptions: position within an operon or gene can affect transcript levels in a manner dependent on Trp codon content.

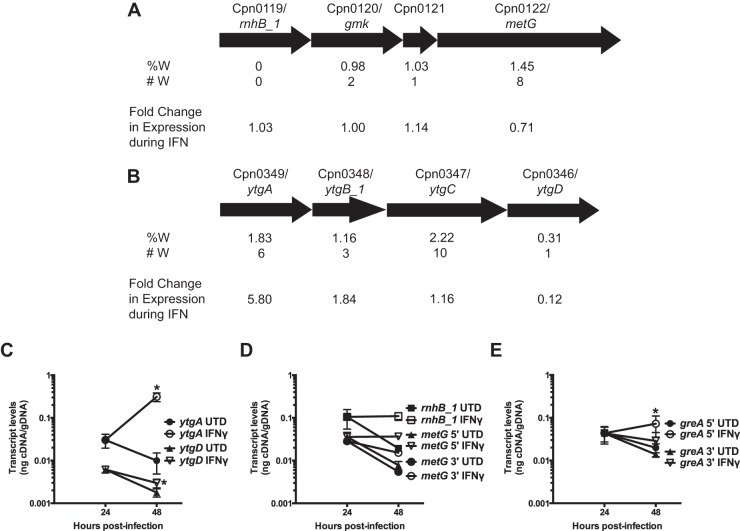

We anticipated that there would be two primary exceptions to our hypothesis and reasoned that these would most likely occur in (i) operons where the first gene was either rich or poor in Trp codons and (ii) large genes with multiple Trp codons. Our rationale was that ribosome stalling at Trp codons would lead to destabilization of the downstream transcript. To test this, we measured the transcript levels at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the ytg and rnhB_1 operons as well as the large gene greA (encoding 11 Trp residues within 722 amino acids).

The organization of the ytg operon is such that the 5′ gene, ytgA, encodes six Trp residues, whereas ytgD encodes one (Fig. 5A). Conversely, the putative rnhB_1 operon is organized such that the 5′ gene rnhB_1 lacks Trp, whereas the 3′ gene metG encodes eight Trp residues (Fig. 5B). One would presume that the operon transcript levels should follow the pattern of the 5′ gene, given the single promoter controlling expression. Our earlier microarray data suggested that ytgA transcripts were increased 5.8-fold, with the other open reading frames (ORFs) showing dramatic decreases toward the 3′ end of the operon (Fig. 5A). When we measured ytgA transcript levels during IFN-γ treatment by RT-qPCR, we observed an increase of roughly 10-fold. There was also a notable difference between the 5′ end and 3′ end of ytgA itself, with the 5′ end displaying an approximately 25% increase over the 3′ end compared to untreated cultures, where the 3′ end is detected within 10% of the 5′ level (data not shown). Remarkably, transcript levels of ytgD were more than 2-fold decreased during IFN-γ treatment (Fig. 5C). This indicates a destabilization of the 3′ end of the ytg operon that appears dependent on upstream Trp codons. In keeping with our prior observations, rnhB_1 transcript levels were unchanged during IFN-γ compared to untreated cultures (Fig. 5B and D). Somewhat surprisingly but in keeping with the operon regulation, metG transcript levels were also unchanged when using a primer set designed at the 5′ end of the gene upstream of all Trp codons. However, when we used a primer set toward the 3′ end (and downstream of 5 of 8 total Trp codons), metG transcripts were 2-fold decreased (Fig. 5D) in keeping with a negative polar effect of Trp codons on downstream sequences. Overall, the metG example illustrates how a high-Trp gene may behave transcriptionally like a low-Trp gene.

FIG 5.

Tryptophan codons have destabilizing effects on downstream transcripts. Shown is determination of the effect of Trp (W) codons on transcript levels within operons and large genes in C. pneumoniae during IFN-γ-mediated persistence. (A and B) Schematic representation of the (A) ytg and (B) rnhB_1 operons, including the percentage (%W) and number (#W) of Trp codons within the open reading frames. Arrow sizes represent the relative sizes of the genes in the operons. Also shown is the fold change in transcript levels during IFN-γ persistence between 24 and 48 h postinfection, as measured by microarray (42). (C to E) Nucleic acid samples were collected from untreated (solid symbols) and IFN-γ-treated (open symbols) C. pneumoniae-infected HEp2 cells at 24 and 48 h postinfection. Transcript levels for the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR and normalized to genomic DNA (nanograms of cDNA/gDNA). (C) Quantification of transcript levels of ytgA and ytgD. (D) Quantification of transcript levels of rnhB_1 and metG. Two different primer sets were used to quantify metG transcripts: one targeting the 5′ end of the gene and another the 3′ end. (E) Quantification of transcript levels of greA using primer sets designed against the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene. (See the text for more detail.) All transcript data are the average from 3 experiments (except metG 3′, where n = 2) with standard deviations displayed. *, P ≤ 0.05 for 48-hpi IFN-γ versus 24-hpi IFN-γ.

To determine if the polar effect of Trp codons would apply within large monocistronic units, we examined greA transcription using primer sets designed near the ends of the gene. The GreA protein contains 11 Trp residues. We observed that the 5′ end of greA, downstream of 3 Trp codons, was increased approximately 2-fold in IFN-γ-treated cultures (Fig. 5E). Conversely, the 3′ end of the gene, downstream of 8 Trp codons, was decreased approximately 2-fold in IFN-γ treatment, reflecting an overall 4-fold decrease compared to the 5′ end. In untreated cultures, the difference between the ends of greA was less than 10%. Overall, the transcript levels of greA would appear to be unchanged or even decreased, in apparent opposition to our hypothesis, yet the Trp codons clearly affect the transcript levels at each end of the gene.

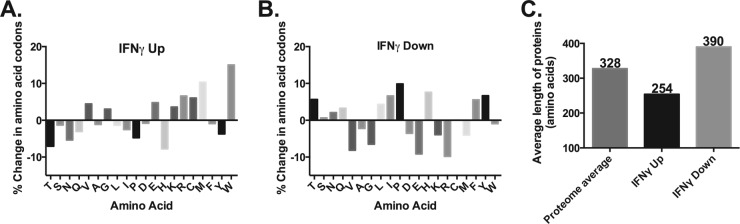

A reanalysis of the microarray data supports a role for Trp codon content in increased transcription.

To test our hypothesis on a larger scale, we revisited our previous microarray data (42) and normalized the changes in transcription based on codon content (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The average percentage of Trp codons within C. pneumoniae genes is 0.96%, or roughly 1 Trp codon per 100 amino acids. In Fig. 6, the RB profile at 24 hpi is represented by the 0 value on the y axis. Importantly, we excluded all late genes, those transcribed during RB-to-EB differentiation, from the analysis (85 total) as their increased transcription (63 of 85) during IFN-γ-mediated persistence is almost certainly due to the inability to effectively regulate their expression; no late gene protein products are present, and no EBs are produced (42). In addition, late genes are typically poor in Trp codons (average of 0.84%), and thus this artificially skews the analysis.

FIG 6.

Codon content analysis of C. pneumoniae transcript data during IFN-γ-mediated persistence reveals an enrichment of tryptophan codon-containing genes in the upregulated data set. Microarray data from IFN-γ-treated C. pneumoniae were analyzed based on the codon content of the genes that were at least 2-fold increased (A [IFNγ Up]) or 2-fold decreased (B [IFNγ Down]). The percentage change in the codon content is reflected on the y axis, whereas the individual single-letter code for the amino acid is listed on the x axis. The 0 value reflects the average C. pneumoniae codon content of the 24-h postinfection (i.e., RB profile) transcript levels. (C) For the data in panels A and B, the average length of the proteins encoded by the differentially transcribed genes was plotted and compared to the proteome average (328 amino acids).

In total, 226 genes displayed increased transcription of more than 2-fold between 24 hpi and 48 hpi during IFN-γ-mediated persistence, and these genes had an average Trp codon content of 1.1% (versus 1.05% if late genes are included), which corresponds to an overall Trp enrichment of +15% (P < 0.05, r = 0.1371, by Spearman rank correlation) (Fig. 6A). These genes also showed an enrichment of +10% in methionine (Met), but this was not statistically significant. All other amino acids showed changes of less than 10%. Intriguingly, of the 15 genes that showed an increase of transcripts of at least 10-fold, these had an average Trp enrichment of +51% compared to +9.7% for Met (data not shown). Conversely, for the 296 genes that displayed decreased transcription of more than 2-fold, the average Trp content was unchanged (0.95%), corresponding to a net enrichment of −1% that was not statistically significant (Fig. 6B). Several amino acids approached a 10% change in codon abundance in the downregulated genes, including proline (+9.9%), valine (−8.2%), glutamate (−9.2%), and arginine (−9.8%), but none of these changes were significant.

Because of our findings with operons and large genes where the 3′ ends appeared to be destabilized, we next asked the question whether there was a correlation between the levels of transcripts and the size of the encoded protein. Our hypothesis was that larger gene transcripts would be less abundant. The average size of C. pneumoniae proteins is 328 amino acids (Fig. 6C). Here, we found that the most upregulated transcripts were for smaller gene products with an average size of 254 amino acids. The opposite profile was found for the downregulated transcripts, where these gene products had an average size of 390 amino acids. Overall, the microarray data show a trend that is consistent with our hypothesis and our RT-qPCR analysis, which is remarkable given the caveats we have previously characterized concerning operons and large genes.

DISCUSSION

Most bacteria respond to amino acid limitation by enacting the stringent response (58). This global regulatory response is evolved to effectively shut down anabolic pathways and activate catabolic processes that result in an increase in the free amino acid pool such that the organism can continue growing. These effects are mediated by a polyphosphorylated guanine analog, (p)ppGpp, the levels of which are controlled by the enzymes RelA and SpoT (59). During amino acid starvation, an increase in uncharged tRNAs will lead to ribosomes' stalling on transcripts, and this activates RelA to produce (p)ppGpp. ppGpp in turn acts as a global regulator by binding RNA polymerase, among other targets, and modifying its activity in a promoter-dependent manner (60). This global regulatory “program” is highly conserved in bacteria.

Interestingly, no functional stringent response has been described in obligate intracellular bacteria like Chlamydia. Why these highly adapted organisms would eliminate this pathway is not clear and may reflect the relatively stable nutritional environment within a host cell. However, Chlamydia can experience amino acid starvation. IFN-γ, an immune cytokine produced during chlamydial infections (61, 62), can induce a Trp-limiting environment in human epithelial cells by activating expression of the enzyme IDO, which cleaves the indole ring of Trp (23). Thus, IFN-γ treatment leads to an enzymatically controlled Trp starvation state. Importantly, Chlamydia is a Trp auxotroph and acquires this essential amino acid from the host cell. By analogy with other bacteria, when Chlamydia is exposed to amino acid starvation, an increase in uncharged tRNAs will lead to ribosome stalling on transcripts. However, what occurs after this at a regulatory level is not known. Descriptively, it leads to a persistent growth state characterized by a cessation in cell division and aberrantly enlarged organisms that remain viable (14, 25). Thus, understanding how Chlamydia responds to Trp starvation will facilitate our understanding of chlamydial persistence more generally.

Stringent response (so-called “relaxed”) mutants have been created in other bacteria to study the effects of this system. The main characteristic of these mutants is that they do not downregulate stable RNA synthesis in response to amino acid starvation (e.g., see references 63–66). Some mutants have been examined by large-scale transcriptomic analyses but not in the context of codon influence on transcription. Also not clear is whether these studies used appropriate normalization methods given the tendency to rely on 16S rRNA or relative expression to another gene as a normalizer (e.g., see references 67–70). We previously observed that Chlamydia does not downregulate stable RNA synthesis during IFN-γ-mediated Trp limitation (42), and as such, this would qualify Chlamydia as a relaxed mutant.

Why would Chlamydia eliminate the stringent response when it is clearly affected by nutrient limitation? Interestingly, different chlamydial species have adapted to respond to the IFN-γ effectors of their host species. For example, in the mouse, IFN-γ does not induce IDO (27): thus, Chlamydia muridarum does not encode mechanisms for responding specifically to Trp. In the guinea pig, IFN-γ does induce IDO, but Chlamydophila caviae contains an operon that recycles kynurenine, the metabolic product of IDO activity, to Trp (71). In humans, as described, IFN-γ induces IDO. C. trachomatis has eliminated most Trp biosynthetic genes, with the exception of the terminal genes (trpBA) in the operon that use indole to produce Trp (45). One hypothesis is that C. trachomatis will use indole generated by normal flora (in the female genital tract) to withstand the IDO-mediated Trp-limiting environment, and thus, it would never be exposed to Trp starvation (72, 73). Thus, for all these species, it is easy to envision the advantage in eliminating the now superfluous stringent response. However, once C. trachomatis ascends the genital tract and reaches areas that are devoid of normal flora producing indole, it will become persistent. In this scenario, persistent C. trachomatis could contribute to chronic sequelae without producing infectious EBs. C. pneumoniae, on the other hand, does not carry trpBA, suggesting that the respiratory tract is an unlikely source of indole and may explain why C. pneumoniae becomes persistent more readily.

We previously observed that chlamydial transcription was globally increased even though translation was generally decreased during IFN-γ-mediated persistence (42). That a bacterium would globally increase transcription in response to a stress is difficult to rationalize. We hypothesized that the Trp codon content of a given gene would determine its transcription during Trp limitation. We analyzed the transcription of 25 genes (2.3% of the genome) by RT-qPCR and observed patterns of transcription that were generally consistent with the hypothesis. Furthermore, an analysis of prior microarray data based on codon content supported a role for increased abundance of Trp codon-containing transcripts during IFN-γ-mediated persistence. We also made the surprising observation that there was a differential pattern of expression based on the size of the gene, with a correlation between larger genes and downregulation and vice versa.

Not surprisingly, we did find exceptions to our hypothesis. In the first instance, dnaJ transcripts were significantly increased 2-fold, even though DnaJ lacks Trp. Why this should be is not clear. DnaJ is a cochaperone of DnaK that functions in proteostasis to limit misfolded proteins (74, 75). Given that Trp limitation leads to a decrease in global translation rates (42), one would anticipate a decreased need for chaperone function under these conditions. Further work will be necessary to understand the promoter elements that lead to the increased transcription of dnaJ during Trp limitation in Chlamydia as well as what the significance of this finding is.

In a second instance, we observed apparent exceptions to our hypothesis in the context of operons and large genes. For example, metG transcripts (when measured at the 5′ end upstream of all Trp codons) were unchanged even though MetG encodes eight Trp residues. However, the 5′ gene of the operon, rnhB_1 (rnhB_1 encodes 0 Trp residues), was also unchanged. These data suggest that the regulatory information controlling transcript levels of operons is encoded within the promoter and determined by the Trp codon content of the 5′ gene.

We also analyzed the ytg operon because of the Trp content of its proteins and because of our initial microarray data (Fig. 5A). ytgA transcripts were dramatically increased, as expected given its high Trp codon content, whereas transcripts for the 3′ gene ytgD were significantly decreased. Similarly, we observed that the 3′ end of greA was significantly decreased in abundance compared to the 5′ end during IFN-γ-mediated Trp limitation. greA encodes 11 Trp residues. Taken together, these data indicate an apparent destabilization of transcripts downstream of Trp codons and are supported by the microarray data showing larger gene transcripts being less abundant. We hypothesize this is due to one of two factors associated with ribosome stalling at Trp codons: either the 3′ end of the transcript is exposed for degradation by RNases or the transcription terminator Rho is activated to stop transcription (i.e., Rho-dependent polarity). We are examining these possibilities.

In further support of the effect of Trp on downstream sequences, we did not observe a positive correlation between the amount of Trp codons within a gene and its overall increased transcript level. For instance, transcripts for obg (2 W codons) were more than 8-fold increased compared to those for nusG (4 W codons), which were less than 3-fold increased (Table 1). However, these differences may also be explained by the location of the primer sets used. That for obg was downstream of a single Trp codon, whereas that for nusG was downstream of two Trp codons. Thus, even within a smaller gene, Trp codons may have an effect on overall transcript abundance.

Is this transcriptional response unique to Chlamydia, or does it represent a typical relaxed (e.g., relA) mutant? Interestingly, Chlamydia has maintained the gene dksA, which is a cofactor or facilitator of the stringent response in other bacteria that possess this system. In some instances, overexpression of DksA can compensate for the lack of a stringent response (77). However, we observed a decrease in dksA transcripts; thus, this is not its likely function in Chlamydia. Rather, DksA in Chlamydia may be critical for transcription elongation and mediating conflicts between the replication and transcriptional machineries (78). Further work will be necessary to determine the role of DksA in Chlamydia.

The specific mechanism that controls this unusual response of Chlamydia to amino acid starvation remains to be determined. Comparing and contrasting the responses of C. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis may aid in this. How does the Trp content of a gene feed back to influence transcription? Is it a sequence-encoded event, or is there a global regulator controlling this response? Is this response the consequence of the inability to translate key transcription factors? Recent advances in chlamydial genetic approaches should allow these questions to be addressed (79), and we are currently implementing such strategies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Caldwell (Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID) for eukaryotic cell stocks and antibodies against C. pneumoniae AR39 and R. Morrison (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) for the antibody against cHsp60_1. We thank M. Chaussee (University of South Dakota) and R. Carabeo (Washington State University) for critical reading of the manuscript and fruitful discussions.

S.P.O. and E.A.R. were supported by start-up funds from the University of South Dakota.

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00377-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schachter J, Storz J, Tarizzo ML, Bogel K. 1973. Chlamydiae as agents of human and animal diseases. Bull World Health Organ 49:443–449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grayston JT. 1992. Infections caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR. Clin Infect Dis 15:757–761. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mabey DCW, Solomon AW, Foster A. 2003. Trachoma. Lancet 362:223–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13914-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Datta SD, Sternberg M, Johnson RE, Berman S, Papp JR, McQuillan G, Weinstock H. 2007. Gonorrhea and chlamydia in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999 to 2002. Ann Intern Med 147:89–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AbdelRahman YM, Belland RJ. 2005. The chlamydial developmental cycle. FEMS Microbiol Rev 29:949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore ER, Ouellette SP. 2014. Reconceptualizing the chlamydial inclusion as a pathogen-specific parasitic organelle: an expanded role for Inc proteins. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:157. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, Koonin EV, Davis RW. 1998. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunham RC, MacLean IW, Binns B, Peeling RW. 1985. Chlamydia trachomatis: its role in tubal infertility. J Infect Dis 152:1275–1282. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor-Robinson D, Gilroy CB, Thomas BJ, Keat AC. 1992. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis DNA in joints of reactive arthritis patients by polymerase chain reaction. Lancet 340:81–82. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90399-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saikku P, Leinonen M, Mattila K, Ekman WR, Nieminen MS, Mäkelä PH, Huttunen JK, Valtonen V. 1988. Serological evidence of an association of a novel Chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet ii:983–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn DL. 1995. Treatment of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in adult asthma: a before-after trial. J Fam Pract 41:345–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beatty WL, Morrison RP, Byrne GI. 1994. Persistent chlamydiae: from cell culture to a paradigm for chlamydial pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev 58:686–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wyrick PB. 2010. Chlamydia trachomatis persistence in vitro: an overview. J Infect Dis 201(Suppl 2):S88–S95. doi: 10.1086/652394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beatty WL, Byrne GI, Morrison RP. 1993. Morphologic and antigenic characterization of interferon gamma-mediated persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:3998–4002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raulston JE. 1997. Response of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar E to iron restriction in vitro and evidence for iron-regulated chlamydial proteins. Infect Immun 65:4539–4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson CC, Carabeo RA. 2011. An optimal method of iron starvation of the obligate intracellular pathogen, Chlamydia trachomatis. Front Microbiol 2:20. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011/00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatch TP. 1975. Competition between Chlamydia psittaci and L cells for host isoleucine pools: a limiting factor in chlamydial multiplication. Infect Immun 12:211–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harper A, Pogson CI, Jones ML, Pearce JH. 2000. Chlamydial development is adversely affected by minor changes in amino acid supply, blood plasma amino acid levels, and glucose deprivation. Infect Immun 68:1457–1464. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.3.1457-1464.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones ML, Gaston JS, Pearce JH. 2001. Induction of abnormal Chlamydia trachomatis by exposure to interferon-gamma or amino acid deprivation and comparative antigenic studies. Microb Pathog 30:299–309. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis ME, Belland RJ, AbdelRahman YM, Beatty WL, Aiyar AA, Zea AH, Greene SJ, Marrero L, Buckner LR, Tate DJ, McGowin CL, Kozlowski PA, O'Brien M, Lillis RA, Martin DH, Quayle AJ. 2014. Morphologic and molecular evaluation of Chlamydia trachomatis growth in human endocervix reveals distinct growth patterns. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:71. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrne GI, Lehmann LK, Landry GJ. 1986. Induction of tryptophan catabolism is the mechanism for gamma-interferon-mediated inhibition of intracellular Chlamydia psittaci replication in T24 cells. Infect Immun 53:347–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beatty WL, Morrison RP, Byrne GI. 1994. Immunoelectron-microscopic quantitation of differential levels of chlamydial proteins in a cell culture model of persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun 62:4059–4062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfefferkorn ER. 1984. Interferon gamma blocks the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts by inducing the host cells to degrade tryptophan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:908–912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouellette SP, Dorsey FC, Moshiach S, Cleveland JL, Carabeo RA. 2011. Chlamydia species-dependent differences in the growth requirement for lysosomes. PLoS One 6:e16783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beatty WL, Morrison RP, Byrne GI. 1995. Reactivation of persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in cell culture. Infect Immun 63:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas SM, Garrity LF, Brandt CR, Schobert CS, Feng GS, Taylor MW, Carlin JM, Byrne GI. 1993. IFN-gamma-mediated antimicrobial response. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-deficient mutant host cells no longer inhibit intracellular Chlamydia spp. or Toxoplasma growth. J Immunol 150:5529–5534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roshick C, Wood H, Caldwell HD, McClarty G. 2006. Comparison of gamma interferon-mediated antichlamydial defense mechanisms in human and mouse cells. Infect Immun 74:225–238. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.225-238.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibana JA, Belland RJ, Zea AH, Schust DJ, Nagamatsu T, AbdelRahman YM, Tate DJ, Beatty WL, Aiyar AA, Quayle AJ. 2011. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity by levo-1-methyl tryptophan blocks gamma interferon-induced Chlamydia trachomatis persistence in human epithelial cells. Infect Immun 79:4425–4437. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05659-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw AC, Christiansen G, Birkelund S. 1999. Effects of interferon gamma on Chlamydia trachomatis serovar A and L2 protein expression investigated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 20:775–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrne GI, Ouellette SP, Wang Z, Rao JP, Lu L, Beatty WL, Hudson AP. 2001. Chlamydia pneumoniae expresses genes required for DNA replication but not cytokinesis during persistent infection of HEp-2 cells. Infect Immun 69:5423–5429. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5423-5429.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gérard HC, Krauße-Opatz B, Wang Z, Rudy D, Rao JP, Zeidler H, Schumacher HR, Whittum-Hudson JA, Köhler L, Hudson AP. 2001. Expression of Chlamydia trachomatis genes encoding products required for DNA synthesis and cell division during active versus persistent infection. Mol Microbiol 41:731–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathews S, George C, Flegg C, Stenzel D, Timms P. 2001. Differential expression of ompA, ompB, pyk, nlpD, and Cpn0585 genes between normal and interferon-gamma treated cultures of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Microb Pathog 30:337–345. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gérard HC, Freise J, Wang Z, Roberts G, Rudy D, Krauß-Opatz B, Köhler L, Zeidler H, Schumacher HR, Whittum-Hudson JA, Hudson AP. 2002. Chlamydia trachomatis genes whose products are related to energy metabolism are expressed differentially in active versus persistent infection. Microbes Infect 4:13–22. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molestina RE, Klein JB, Miller RD, Pierce WH, Ramirez JA, Summersgill JT. 2002. Proteomic analysis of differentially expressed Chlamydia pneumoniae genes during persistent infection of HEp-2 cells. Infect Immun 70:2976–2981. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2976-2981.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belland RJ, Nelson DE, Virok D, Crane DD, Hogan D, Sturdevant D, Beatty WL, Caldwell HD. 2003. Transcriptome analysis of chlamydial growth during IFN-gamma-mediated persistence and reactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:15971–15976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535394100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukhopadhyay S, Miller RD, Summersgill JT. 2004. Analysis of altered protein expression patterns of Chlamydia pneumoniae by an integrated proteome-works system. J Proteome Res 3:878–883. doi: 10.1021/pr0400031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goellner S, Schubert E, Liebler-Tenorio E, Hotzel H, Saluz HP, Sachse K. 2006. Transcriptional response patterns of Chlamydophila psittaci in different in vitro models of persistent infection. Infect Immun 74:4801–4808. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01487-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polkinghorne A, Hogan RL, Vaughan L, Summersgill JT, Timms P. 2006. Differential expression of chlamydial signal transduction genes in normal and interferon gamma-induced persistent Chlamydophila pneumoniae infections. Microbes Infect 8:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klos A, Thalmann J, Peters J, Gérard HC, Hudson AP. 2009. The transcript profile of persistent Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae in vitro depends on the means by which persistence is induced. FEMS Microbiol Lett 291:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timms P, Good D, Wan C, Theodoropoulos C, Mukhopadhyay S, Summersgill JT, Mathews S. 2009. Differential transcriptional responses between the interferon-gamma-induction and iron-limitation models of persistence for Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 42:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouellette SP, AbdelRahman YM, Belland RJ, Byrne GI. 2005. The Chlamydia pneumonia type III secretion-related lcrH gene clusters are developmentally expressed operons. J Bacteriol 187:7853–7856. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7853-7856.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ouellette SP, Hatch TP, AbdelRahman YM, Rose LA, Belland RJ, Byrne GI. 2006. Global transcriptional upregulation in the absence of increased translation in Chlamydia during IFNgamma-mediated host cell tryptophan starvation. Mol Microbiol 62:1387–1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison RP. 2000. Differential sensitivities of Chlamydia trachomatis strains to inhibitory effects of gamma interferon. Infect Immun 68:6038–6040. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.10.6038-6040.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kane CD, Vena RM, Ouellette SP, Byrne GI. 1999. Intracellular tryptophan pool sizes may account for differences in gamma interferon-mediated inhibition and persistence of chlamydial growth in polarized and nonpolarized cells. Infect Immun 67:1666–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wood H, Fehlner-Gardner C, Berry J, Fischer E, Graham B, Hackstadt T, Roshick C, McClarty G. 2003. Regulation of tryptophan synthase gene expression in Chlamydia trachomatis. Mol Microbiol 49:1347–1359. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belland RJ, Zhong G, Crane DD, Hogan D, Sturdevant D, Sharma J, Beatty WL, Caldwell HD. 2003. Genomic transcriptional profiling of the developmental cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:8478–8483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331135100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hatch TP, Miceli M, Sublett JE. 1986. Synthesis of disulfide-bonded outer membrane proteins during the developmental cycle of Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol 165:379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Everett KD, Hatch TP. 1991. Sequence analysis and lipid modification of the cysteine-rich envelope proteins of Chlamydia psittaci 6BC. J Bacteriol 173:3821–3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wichlan DG, Hatch TP. 1993. Identification of an early-stage gene of Chlamydia psittaci 6BC. J Bacteriol 175:2936–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouellette SP, Karimova G, Subtil A, Ladant D. 2012. Chlamydia co-opts the rod shape-determining proteins MreB and Pbp2 for cell division. Mol Microbiol 85:164–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ouellette SP, Rueden KJ, Gauliard E, Persons L, de Boer PA, Ladant D. 2014. Analysis of MreB interactors in Chlamydia reveals a RodZ homolog but fails to detect an interaction with MraY. Front Microbiol 5:279. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Polkinghorne A, Vaughan L. 2011. Chlamydia abortus YhbZ, a truncated Obg family GTPase, associates with the Escherichia coli large ribosomal subunit. Microb Pathog 50:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karunakaran KP, Noguchi Y, Read TD, Cherkasov A, Kwee J, Shen C, Nelson CC, Brunham RC. 2003. Molecular analysis of the multiple GroEL proteins of Chlamydiae. J Bacteriol 185:1958–1966. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1958-1966.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu AY, Houry WA. 2007. ClpP: a distinctive family of cylindrical energy-dependent serine proteases. FEBS Lett 581:3749–3757. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson CC, Griffiths C, Nicod SS, Lowden NM, Wigneshweraraj S, Fisher DJ, McClure MO. 2015. The Rsb phosphoregulatory network controls availability of the primary sigma factor in Chlamydia trachomatis and influences the kinetics of growth and development. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005125. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan M, Wong B, Engel JN. 1996. Transcriptional organization and regulation of the dnaK and groE operons of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol 178:6983–6990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanson BR, Tan M. 2015. Transcriptional regulation of the Chlamydia heat shock stress response in an intracellular infection. Mol Microbiol 97:1158–1167. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chatterji D, Ojha AK. 2001. Revisiting the stringent response, ppGpp, and starvation signaling. Curr Opin Microbiol 4:160–165. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00182-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magnusson LU, Farewell A, Nyström T. 2005. ppGpp: a global regulator in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol 13:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kanjee U, Ogata K, Houry WA. 2012. Direct binding targets of the stringent response alarmone (p)ppGpp. Mol Microbiol 85:1029–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grifo JA, Jeremias J, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. 1989. Interferon-gamma in the diagnosis and pathogenesis of pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160:26–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90080-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vicetti Miguel RD, Reighard SD, Chavez JM, Rabe LK, Maryak SA, Wiesenfeld HC, Cherpes TL. 2012. Transient detection of chlamydial-specific TH1 memory cells in the peripheral circulation of women with history of Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Am J Reprod Immunol 68:499–506. doi: 10.1111/aji.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaplan S, Atherly AG, Barrett A. 1973. Synthesis of stable RNA in stringent Escherichia coli cells in the absence of charged transfer RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 70:689–692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tauch A, Wehmeier L, Götker S, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. 2001. Relaxed rrn expression and amino acid requirement of a Corynebacterium glutamicum rel mutant defective in (p)ppGpp metabolism. FEMS Microbiol Lett 201:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bugrysheva JV, Godfrey HP, Schwartz I, Cabello FC. 2011. Patterns and regulation of ribosomal RNA transcription in Borrelia burgdorferi. BMC Microbiol 11:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kästle B, Geiger T, Gratani FL, Reisinger R, Goerke C, Borisova M, Mayer C, Wolz C. 2015. rRNA regulation during growth and under stringent conditions in Staphylococcus aureus. Environ Microbiol 17:4394–4405. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brockmann-Gretza O, Kalinowski J. 2006. Global gene expression during stringent response in Corynebacterium glutamicum in presence and absence of the rel gene encoding (p)ppGpp synthase. BMC Genomics 7:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lemos JA, Nascimento MM, Lin VK, Abranches J, Burne RA. 2008. Global regulation by (p)ppGpp and CodY in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 190:5291–5299. doi: 10.1128/JB.00288-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Traxler MF, Summers SM, Nguyen HT, Zacharia VM, Hightower GA, Smith JT, Conway T. 2008. The global, ppGpp-mediated stringent response to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 68:1128–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holley CL, Zhang X, Fortney KR, Ellinger S, Johnson P, Baker B, Liu Y, Janowicz DM, Katz BP, Munson RS Jr, Spinola SM. 2015. DksA and (p)ppGpp have unique and overlapping contributions to Haemophilus ducreyi pathogenesis in humans. Infect Immun 83:3281–3292. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00692-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wood H, Roshick C, McClarty G. 2004. Tryptophan recycling is responsible for the interferon-gamma resistance of Chlamydia psittaci GPIC in indoleamine dioxygenase-expressing host cells. Mol Microbiol 52:903–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Caldwell HD, Wood H, Crane D, Bailey R, Jones RB, Mabey D, MacLean I, Mohammed Z, Peeling R, Roshick C, Schachter J, Solomon AW, Stamm WE, Suchland RJ, Taylor L, West SK, Quinn TC, Belland RJ, McClarty G. 2003. Polymorphisms in Chlamydia trachomatis tryptophan synthase genes differentiate between genital and ocular isolate. J Clin Invest 111:1757–1769. doi: 10.1172/JCI17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aiyar A, Quayle AJ, Buckner LR, Sherchand SP, Chang TL, Zea AH, Martin DH, Belland RJ. 2014. Influence of the tryptophan-indole-IFNγ axis on human genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection: role of vaginal co-infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:72. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jordan R, McMacken R. 1995. Modulation of the ATPase activity of the molecular chaperone DnaK by peptides and the DnaJ and GrpE heat shock proteins. J Biol Chem 270:4563–4569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cho Y, Zhang X, Pobre KF, Liu Y, Powers DL, Kelly JW, Gierasch LM, Powers ET. 2015. Individual and collective contributions of chaperoning and degradation to protein homeostasis in E. coli. Cell Rep 11:321–333. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reference deleted. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Magnusson LU, Gummesson B, Joksimović P, Farewell A, Nyström T. 2007. Identical, independent, and opposing roles of ppGpp and DksA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 189:5193–5202. doi: 10.1128/JB.00330-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tehranchi AK, Blankschien MD, Zhang Y, Halliday JA, Srivatsan A, Peng J, Herman C, Wang JD. 2010. The transcriptional factor DksA prevents conflicts between DNA replication and transcription machinery. Cell 141:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang Y, Kahane S, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Lambden PR, Clarke IN. 2011. Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.