Significance

People tend to incorporate desirable feedback into their beliefs but discount undesirable ones. Such optimistic updating has evolved as an advantageous mechanism for social adaptation and physical/mental health. Here, in three independent studies, we show that intranasally administered oxytocin (OT), an evolutionary ancient neuropeptide pivotal to social adaptation, augments optimistic belief updating by increasing updates and learning of desirable feedback but impairing updates of undesirable feedback. Moreover, the OT-impaired updating of undesirable feedback is more salient in individuals with high, rather than with low, depression or anxiety traits. OT also increases second-order confidence judgment after desirable feedback. These findings reveal a molecular substrate underlying the formation of optimistic beliefs about the future.

Keywords: oxytocin, social adaptation, confidence, belief updating, optimism

Abstract

Humans update their beliefs upon feedback and, accordingly, modify their behaviors to adapt to the complex, changing social environment. However, people tend to incorporate desirable (better than expected) feedback into their beliefs but to discount undesirable (worse than expected) feedback. Such optimistic updating has evolved as an advantageous mechanism for social adaptation. Here, we examine the role of oxytocin (OT)―an evolutionary ancient neuropeptide pivotal for social adaptation―in belief updating upon desirable and undesirable feedback in three studies (n = 320). Using a double-blind, placebo-controlled between-subjects design, we show that intranasally administered OT (IN-OT) augments optimistic belief updating by facilitating updates of desirable feedback but impairing updates of undesirable feedback. The IN-OT–induced impairment in belief updating upon undesirable feedback is more salient in individuals with high, rather than with low, depression or anxiety traits. IN-OT selectively enhances learning rate (the strength of association between estimation error and subsequent update) of desirable feedback. IN-OT also increases participants’ confidence in their estimates after receiving desirable but not undesirable feedback, and the OT effect on confidence updating upon desirable feedback mediates the effect of IN-OT on optimistic belief updating. Our findings reveal distinct functional roles of OT in updating the first-order estimation and second-order confidence judgment in response to desirable and undesirable feedback, suggesting a molecular substrate for optimistic belief updating.

Humans live in a complex, changing social environment. Adapting to the dynamic environment requires learning from feedback to accordingly update beliefs, change decisions, and guide future behaviors (1, 2). The hypothalamic peptide oxytocin (OT) is an evolutionarily ancient neuropeptide implicated in sociality and well-being (3, 4) and has been recently proposed as an important molecular substrate for social adaptation (5). The social adaptation model (5) posits that a fundamental function of OT is to promote adaptation to the social environment, by modifying cognitive processes and emotional responses and adjusting behaviors. Previous research has focused on the impact of OT on a specific stage of the social signal processing stream or a particular behavioral outcome. Intranasally administered OT (IN-OT) has been shown to improve mind reading (refs. 6 and 7; but also see ref. 8), enhance empathic accuracy (9), improve encoding and recognition of happy facial expressions (10, 11), increase eye contact (12), facilitate recognition of relationship words (13), increase in-group favoritism (14, 15), and promote prosocial behaviors (refs. 16 and 17; but also see ref. 18). However, there has been surprisingly little research examining OT effects on the cognitive dynamics during which feedback modifies cognitive processes and behavioral outcomes. Here, we used a two-stage belief-updating task (refs. 19 and 20; SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) in a double-blind, placebo (PL)-controlled design to investigate OT impact on the dynamic processes of belief updating. The belief-updating task required participants to estimate their personal probability of experiencing different adverse life events in the future before (stage 1) and after (stage 2) being provided with feedback (the probability of each event occurring to an average person in a similar environment).

Humans form and update their beliefs in an optimistic manner, i.e., people update desirable (better than expected) news into their beliefs but discount or ignore undesirable (worse than expected) news (2, 19, 21). The oxytocinergic system has been implicated in social learning and optimism. Animal research has shown evidence for a key role of the oxytocinergic system in mediating appetitive and aversive learning in mice (22). Human studies have linked optimism with OT receptor gene function (OXTR; ref. 23). Moreover, IN-OT has been recently used in the treatment for depressive patients (24, 25)—a population characterized by the absence of optimistic belief updating (20). There has been evidence that optimistic updating serves as an advantageous mechanism for individuals’ social adaptation. For example, optimistic updating facilitates individuals’ subjective well-being, physical healthy and success, buffers stress, and reduces anxiety (1, 26–28). Optimism also modulates social relations such that more optimistic individuals have better social connections (28), obtain greater social support (29), have larger social networks (30), and maintain better marital and parental relationships (31, 32). Given these positive effects of optimistic updating for social adaptation and the important role of OT in social adaptation (5), here we predicted that IN-OT would increase optimistic belief updating. More specifically, because optimistic belief updating was driven by enhanced updating and learning of desirable feedback and reduced updating and learning of undesirable feedback (19), we further examined whether IN-OT enhanced optimistic belief updating by impairing updating in response to undesirable feedback, facilitating updating upon receiving desirable feedback, or both.

The effects of OT have been recognized to be modulated by personal milieu (5, 33). IN-OT produced stronger effects on less socially adapted individuals, such as those with high trait anxiety (34), impaired emotion regulation (35), or low emotional sensitivity (36). Because optimism has been implicated in anxiety and depression (26, 27, 37, 38), we further examined whether the effects of IN-OT on optimistic belief updating were moderated by individuals’ depression and anxiety traits. Given the finding of stronger effects of IN-OT on less socially adapted individuals (34–36), we hypothesized that IN-OT would produce stronger effects on belief updating in individuals with high (relative to low) depression and anxiety traits. These hypotheses were tested in study 1 (as a discovery sample) and study 2 (as a replication sample) by asking participants to complete a two-stage belief-updating task 40 min after OT or PL administration.

It has been revealed that an overt judgment (first-order estimation) is usually followed by a second-order judgment (e.g., confidence judgment; ref. 39). These two consecutive processes intertwine with each other and share neural underpinnings to guide decisionmaking (39, 40). Optimistic belief updating is often observed in situations incorporating uncertainty (21, 41), and low confidence is more likely to be associated with subsequent decision changes (40). Thus, we further investigated OT effects on participants’ confidence in their first-order estimates in an independent study 3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Moreover, since alongside sensitivity to perceptions of internal processes (e.g., perceived confidence in estimation), sensitivity to information received externally (e.g., feedback) can facilitate better decisionmaking (42), we also assessed whether IN-OT would influence the degree to which participants accepted feedback (as external information). These measures allowed us to address potential mechanisms underlying OT effects on optimistic belief updating by clarifying whether the OT-induced changes in belief updates were mediated by (i) OT effects on confidence in one’s own estimates, (ii) OT effects on acceptance of the feedback, or (iii) both.

Results

OT Effects on Optimistic Belief Updating.

To estimate OT effects on belief updating, we calculated belief update for each participant defined as the difference in average estimate before and after receiving feedback: Belief Update (BU) = second Estimate – first Estimate. Negative BUs indicated underestimation of encountering aversive events after receiving feedback and reflected optimistic updating. By contrast, positive BUs reflected pessimistic updating. A one-sample test revealed that the mean BU was significantly smaller than 0 [study 1: BU = −1.76, t(1,97) = 2.98, P = 0.004; study 2: BU = −1.37, t(1,94) = 2.80, P = 0.006], indicating reliable optimistic updating across OT and PL groups and replicating previous findings (21, 22). More importantly, an independent-samples t test showed that optimistic updating was greater in IN-OT (vs. PL) group [study 1: t (96) = 2.72, P = 0.008; study 2: t(93) = 2.08, P = 0.041; SI Appendix, Table S1], and this result was also replicated in study 3 [t(112) = 2.76, P = 0.007, SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. S2], indicating that OT shifted participants’ belief updating to be more optimistic.

To test whether IN-OT led to a general underestimation of encountering aversive events before receiving feedback, we compared initial estimates (i.e., first Estimate) between OT and PL groups, but failed to find significant difference (ps > 0.35 in studies 1–3). Thus, the OT-facilitated optimistic updating was not driven by a general effect of underestimation due to IN-OT. The OT effect on optimistic updating remained significant after controlling for memory error of feedback and initial estimates [study 1: F(1,86) = 6.65, P = 0.012; study 2: F(1,87) = 5.04, P = 0.027 study 3: F(1,110) = 9.20, P = 0.003]. In studies 2 and 3, after the memory test, participants further rated event characteristics, i.e., the familiarity, negativity, vividness, arousal, and prior experience of each event (SI Appendix, Table S2). We found a reliable OT effect on optimistic updates after controlling for self-reports of event characteristics [study 2: F(1,88) = 10.74, P = 0.002; study 3: F(1,107) = 11.15, P = 0.001]. Together, these results demonstrated OT-enhanced optimistic belief updating.

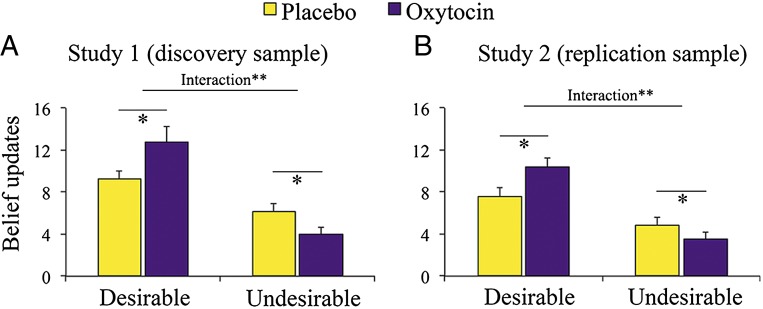

Next, we investigated whether IN-OT increased optimistic updating through reduced updating upon undesirable feedback, enhanced updating upon desirable feedback, or both. BUs upon desirable and undesirable feedback were calculated separately: BUDes = first Estimate − second Estimate (greater BUDes indicated decreased estimates upon desirable feedback, suggesting more desirable updating); BUUndes = second Estimate − first Estimate (greater BUUndes indicated increased estimates upon undesirable feedback, suggesting more undesirable updating). The analyses of variance (ANOVA) with Treatment as a between-subjects factor and Feedback as a within-subject factor revealed a significant main effect of Feedback [study 1: F(1,97) = 33.27, P < 0.001; study 2: F(1,93) = 34.51, P < 0.001, SI Appendix, Table S1], suggesting greater updating upon desirable compared with undesirable feedback. Moreover, there was a significant Treatment × Feedback interaction [study 1: F(1,97) = 8.40, P = 0.005, Fig. 1A; study 2: F(1,93) = 7.28, P = 0.008, Fig. 1B] because IN-OT (vs. PL) enhanced updating upon desirable feedback [study 1: F(1,97) = 6.40, P = 0.013; study 2: F(1,93) = 4.57, P = 0.035] but decreased updating upon undesirable feedback [study 1: F(1,97) = 4.13, P = 0.045; study 2: F(1,93) = 5.56, P = 0.020]. The Treatment × Feedback interactive effect on belief updating was replicated in study 3 [F(1, 112) = 6.047, P = 0.015; SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. S2]. These results provided evidence for distinct OT effects on belief updating upon desirable and undesirable feedback.

Fig. 1.

Distinct OT effects on belief updates upon desirable and undesirable feedback in studies 1 (A) and 2 (B). IN-OT enhanced belief updating upon desirable feedback, but decreased belief updating upon undesirable feedback. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Distinct OT Effects in Individuals with High and Low Depression or Anxiety Scores.

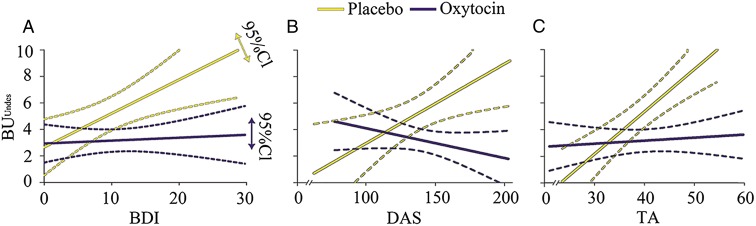

To examine whether the OT effects on belief updating were moderated by depression or anxiety traits, we measured participants’ depression and anxiety scores in studies 2 and 3 (SI Appendix, SI Methods). The reported results of moderation and simple slope analyses were based on data collapsed over studies 2 and 3. The same pattern was observed in studies 2 and 3, respectively (SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4 and Tables S3–S7). Participants’ depressive symptoms, depression-related cognitive distortions, and anxiety traits were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; ref. 43), the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS*) and the Trait Anxiety scale (TA; ref. 44), respectively. These three scales were theoretically distinct in terms of different aims and emphases. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis further confirmed the discriminant validity between the scales in the present sample (SI Appendix, Table S8). Thus, moderation analyses were conducted separately for each scale to assess whether and how depression and anxiety traits moderated the OT effects on belief updating. These analyses showed that the interaction between Treatment and Trait was predictive of BUUndes [BDI: B = −1.79, t(194) = −2.34, P = 0.020, Fig. 2A; DAS: B = −2.25, t(193) = −2.951, P = 0.004, Fig. 2B; TA: B = −2.84, t(194) = −3.82, P < 0.001; Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Tables S9–S11]; but not BUDes (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 and Tables S9–S11), suggesting that individuals’ depression and anxiety traits moderated OT effects on belief updates in response to undesirable feedback.

Fig. 2.

Treatment x Trait interaction predicted belief updating upon undesirable feedback. Under PL, less socially adapted individuals (those with higher BDI, DAS, or TA scores) updated their estimates upon undesirable feedback to a greater degree than those with lower BDI (A), DAS (B), or TA (C) scores. IN-OT normalized the hyperupdating in response to undesirable feedback for less socially adapted individuals.

The significant Treatment × Trait interaction was followed up with simple slope analyses to assess the magnitude of the different effects that contributed to the interaction. Simple slope analyses revealed that the OT effects on BUUndes were significant in individuals who scored high in each trait measurement [BDI: B = −3.910, t(193) = −3.603, P < 0.001; DAS: B = −4.314, t(192) = −3.988, P < 0.001; TA: B = −4.996, t(193) = −4.762, P < 0.001] but not in those who scored low (ps > 0.5). Taking another perspective to interpret the Treatment × Trait interaction, we examined the relationship between trait measurement and BUUndes for OT and PL group, respectively. Under PL, there was a significant correlation between trait scores and BUUndes because individuals who scored high (vs. low) in each trait measure updated their estimates upon undesirable feedback to a greater degree (BDI: B = 1.957, t(193) = 3.395, P = 0.001; DAS: B = 1.637, t(193) = 3.011, P = 0.003; TA: B = 3.053, t(193) = 5.297, P < 0.001). Interestingly, OT treatment normalized the hyperupdates toward undesirable feedback for less socially adapted individuals. Under OT, BUUndes did not vary significantly with individuals’ trait scores (P > 0.25).

Distinct OT Effects on Learning of Desirable and Undesirable Feedback.

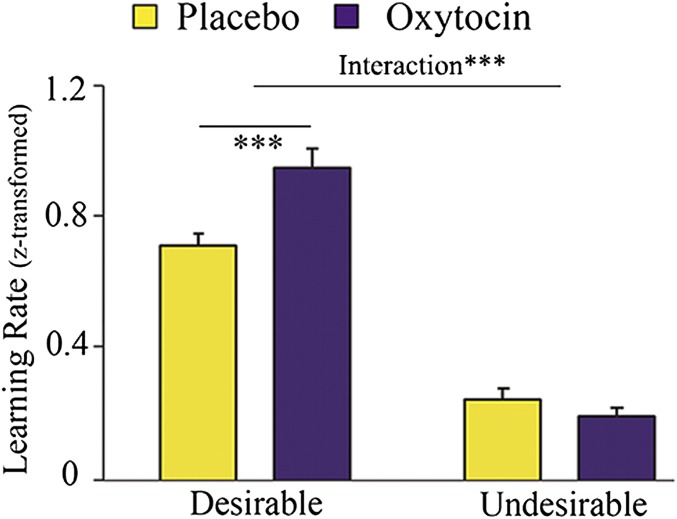

To examine OT effects on the dynamic learning processes of desirable and undesirable feedback, for each participant we calculated the learning rate [i.e., the strength of association between the estimation error (prediction error) and the subsequent updates, SI Appendix, SI Methods], which has been suggested as a computational principle that underlies the observed biased belief formation by pointing to estimation errors as a learning signal (45) and reflects the dynamic learning processes of prediction errors (46). The Treatment × Feedback ANOVA of collapsed data from studies 1–3 revealed a significant main effect of Feedback as participants learned to a greater degree from estimation errors in the desirable (than undesirable) trials [F(1,306) = 246.482, P < 0.001]. Moreover, relative to PL, IN-OT enhanced the learning rate of desirable estimation errors [F(1,306) = 11.779, P = 0.001], but not of undesirable ones (P > 0.2; Fig. 3). A significant Treatment × Feedback interaction on learning rate confirmed that IN-OT selectively increased learning from prediction error in the desirable but not undesirable trials [F(1,306) = 13.687, P < 0.001, Fig. 3]. The same pattern of OT effects on learning rate was observed in each study (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. S6).

Fig. 3.

IN-OT enhanced learning rate related to desirable but not undesirable feedback. ***P < 0.001.

OT Effects on Acceptance of Feedback and Confidence Judgment.

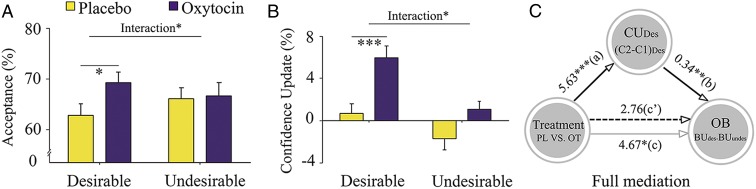

The procedure of study 3 was similar to those in the studies 1 and 2 except that participants were additionally asked to rate their confidence in their first and second estimates, respectively, and their acceptance of the feedback. A 2 (Treatment: OT vs. PL) × 2 (Feedback: Desirable vs. Undesirable) ANOVA of feedback acceptance failed to show significant main effects of Treatment (P > 0.2) or Feedback (F < 1). However, there was a significant Treatment × Feedback interaction on feedback acceptance [F(1,112) = 4.697, P = 0.032; Fig. 4A], because IN-OT (relative to PL) increased participants’ acceptance of desirable feedback [F(1,112) = 4.320, P = 0.040] but failed to influence the acceptance of undesirable feedback (P > 0.8).

Fig. 4.

(A) IN-OT increased participants’ acceptance of desirable (but not undesirable) feedback. (B) OT increased participants’ confidence in their estimates after receiving desirable but not undesirable feedback. (C) Moreover, the OT effect on optimistic bias (OB) in belief updating was mediated by the effect of OT on confidence update upon desirable feedback (CUdes). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Confidence updates (confidence judgment of second Estimate minus that of first Estimate, i.e., CU = C2 – C1) were also subjected to ANOVAs with Treatment as a between-subjects factor and Feedback as a within-subject factor. There was a significant main effect of Feedback [F(1,112) = 17.966, P < 0.001] as participants demonstrated increased confidence in their estimates after receiving desirable compared with undesirable feedback. Moreover, there was a significant Treatment × Feedback interaction on CU [F(1,112) = 4.535, P = 0.035; Fig. 4B]. IN-OT (relative to PL) increased participants’ confidence in their estimates after they had received desirable [F(1,112) = 13.277, P < 0.001] but not undesirable feedback (P > 0.1). Under PL, participants’ confidence did not change before or after receiving either desirable (F < 1) or undesirable feedback (P > 0.1). Under OT, participants demonstrated increased confidence in their estimates after receiving desirable feedback [F(1,56) = 28.099, P < 0.001] but not undesirable feedback (P > 0.1). These results provided further evidence that IN-OT (vs. PL) produced distinct effects on the second-order confidence judgments, as well as acceptance, in response to desirable and undesirable feedback.

To further assess whether the OT-facilitated optimistic belief updating was mediated by (i) the OT effect on confidence updates, (ii) the OT effect on feedback acceptance, or (iii) both, we first examined the relationship between the optimistic bias in belief updating (OB, defined as BUDes − BUUndes) and measures of confidence/acceptance. We found that OB was significantly correlated only with CUDes (r = 0.328, P < 0.001). There was no evidence for reliable correlations between OB and CUUndes (r = 0.110, P = 0.245) or between OB and acceptance of desirable (r = −0.026, P = 0.780) or undesirable feedback (r = −0.013, P = 0.887). We then conducted a mediation analysis (SI Appendix, SI Methods) to estimate whether the OT impact on OB was mediated by the OT effect on confidence updating. The mediation analysis confirmed that the OT effect on OB was mediated by its effect on confidence updating upon desirable feedback (Sobel test: t = 2.36, P = 0.018; SI Appendix, Fig. 4C and Tables S12–S15). The stepwise regression excluding Treatment was no longer significant when putting together with CUDes, B = 2.76, t(111) = 1.42, P = 0.157, compared with initial coefficient, B = 4.67, t(112) = 2.46, P = 0.016, suggesting that the OT effect on CUDes acted as a full mediator of the OT effect on OB. A bootstrap resampling analysis (SI Appendix, SI Methods) of the effect size indicated that this mediation effect was different from zero with 95% confidence (confidence intervals: 0.58–4.32).

Matched Mood and Trait Between OT and PL Groups.

OT and PL groups did not differ in age, trait optimism, mood, anxiety, depression-related cognitive distortions or symptoms, self-reports of event characteristics (SI Appendix, Tables S2 and S16–S18). Moreover, neither participants’ memory performance nor reaction times during first and second estimation differed significantly between OT and PL groups (SI Appendix, Tables S19 and S20), suggesting that the IN-OT effects on belief updating cannot be attributed to OT-induced changes in cognitive abilities (e.g., reaction times, memory performance on feedback).

Discussion

The updating of beliefs upon feedback and adjusting behavior accordingly are pivotal to successful adaptation in a changing environment. Optimistic updating has evolved as an adaptive mechanism for physical and mental health (1, 2, 26–28). Here, we showed evidence supporting an impact of OT on optimistic belief updating. Specifically, we demonstrated that IN-OT increased belief updating in response to desirable feedback but reduced updating upon undesirable feedback. The distinct OT effects on belief updating were also evident on the learning rate, i.e., OT selectively facilitated participants’ learning from desirable but not undesirable prediction error to update their belief. Our findings complemented previous findings on OT effects on the processing of social signals (10–15) by uncovering the OT impact on dynamic cognitive processes during belief formation and updating. Our results suggest that OT is a key molecular substrate for optimistic belief updating and plays opposing functional roles in belief updating upon desirable versus undesirable feedback.

Our results indicated that IN-OT (vs. PL) did not influence estimation times and memory of feedback, suggesting that the OT effects on optimistic updating were not driven by a general OT effect on attention or cognitive abilities. These results were in line with previous findings that optimistic updating could not be interpreted purely on the basis of selective attention, cognitive, or mnemonic abilities in processing desirable and undesirable feedback (19, 20, 45), but relied on a learning process involving asymmetric information integration (20, 41). It has been proposed that the uncertainty in prior knowledge relative to that of new data determines how posterior beliefs are formed (47). The more ambiguous and open to interpretation information is, the stronger the optimistic updating appears to be (41). Consistent with this proposition, we showed that the OT effect on optimistic updating was mediated by the effect of OT on confidence updating upon desirable feedback, suggesting a potential mechanism underlying OT-facilitated optimistic updating. IN-OT might increase individuals’ trust in information about others (i.e., an average person), thus adjusting their belief during the second estimation with more confidence, especially in the desirable condition.

The findings of OT studies have suggested several mechanisms underlying OT effects on social cognition (5, 33) that, however, would predict different OT effects on updating of desirable and undesirable feedback. For example, the social motivation hypothesis, which proposes that OT mainly increases intrinsic reward from social interaction (48), predicts that IN-OT would facilitate updating upon desirable feedback but produce little effect on updating upon undesirable feedback. The social salience hypothesis, which suggests that OT enhances sensitivity to and salience of social cues independently of valence (33, 49), predicts that OT would increase learning and updating of both desirable and undesirable feedback. The current findings of opposing OT effects on belief updating upon desirable versus undesirable feedback cannot be explained by these hypotheses. The social adaptation model (5), which proposes that both reducing negative experiences and enhancing positive experiences are facilitative of well-being and promote social adaptation, predicts that IN-OT facilitates learning and updating of desirable feedback and diminishes learning and updating of undesirable feedback. Thus, our findings that OT increased updates from desirable feedback but reduced updates from undesirable feedback fit well with the social adaptation model (5).

Accumulating evidence has shown stronger effects of OT in individuals with high trait anxiety (34), high autistic traits (9), impaired emotion regulation (35), low emotional sensitivity (36), or high attachment avoidance (50). IN-OT also benefits individuals with mental disorders, such as anxiety disorder (51), autism (52), and depression (24, 25). The social adaption model of OT function proposed stronger OT effect on social processes in less socially adapted individuals (5). In support of this model, we found that the OT-reduced updating upon undesirable feedback was selectively observed in less socially adapted individuals (i.e., those with higher depression or anxiety trait). The finding that IN-OT normalized the hyperupdates upon undesirable feedback in less-adapted individuals has important clinical implications for OT treatment in depression, which is characterized by the lack of optimistic updating (2, 20). Although IN-OT has been applied to depression in a few clinical trials (24, 25), the cognitive mechanisms underlying the potential therapeutic effect of OT in depressed patients remain unclear. Our findings suggest a potential cognitive mechanism through which IN-OT ameliorates pessimism in depression.

However, some previous studies have shown stronger OT effects in more socially adapted individuals such as those with low attachment anxiety (53) or low social anxiety (54). It has been suggested that a crucial factor determining these inconsistent results may lie in the social focus of trait measures (54). The studies, showing stronger OT effects in well-adapted individuals, used social-oriented trait measurement, such as the attachment anxiety scale that measured the attachment bond between participants and their parents (53). However, the studies showing stronger OT effects in less socially adapted individuals mainly used self-centered measures, such as anxiety traits measured by State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T) (34), sociocognitive skills (9), or emotional sensitivity/regulation (35, 36). Similarly, we showed stronger OT effects in individuals with less socially adapted traits as measured by self-centered measures such as STAI-T, DAS (one’s own maladaptive thinking patterns), and BDI (depressive symptoms). Taken together, the social-oriented and self-centered traits may interact with OT effects on cognition and behavior in different fashions.

Interestingly, we found a significant Treatment × Trait interaction on undesirable but not desirable belief updating. The OT effect on desirable updating was not modulated by anxiety or depressive traits, suggesting a general OT-increased desirable updating across individuals. Belief updating upon desirable feedback did not vary as a function of individuals’ trait scores under PL, thus left no opportunity for IN-OT to normalize “abnormal” belief updating upon desirable feedback. Alternatively, a large variation (especially in the severe end) in trait measures may be required to reveal significant relationships between individuals’ traits and belief updating upon desirable feedback (20). However, the current study recruited only healthy participants with a small variation in each trait scale (SI Appendix, Table S8). These possible accounts can be addressed in future research by examining the Treatment × Trait interactions in samples with a large variation in trait scores or in clinical populations. Whereas optimistic updating is adaptive for mental health, excessive optimism, especially ignoring undesirable information, can be maladaptive (1, 2, 55) and makes people less likely to take precautionary actions (56). Given that well-adapted individuals already show strong discounting of undesirable feedback under PL, reducing updating upon undesirable feedback could be hazardous for this cohort. Thus, the finding that OT did not reduce belief updating of undesirable feedback in well-adapted individuals may also reflect an adaptive mechanism for this cohort.

Our results were consistent with previous findings of distinct OT effects on positive and negative social-affective processes (5). IN-OT facilitated responses to positive social cues, increased positive social memory, and promoted positive value transmission to social interactions (5, 15, 33). Our findings suggested that OT-induced belief updates were biased toward positive information. Thus, OT may make positive information easier to be accessed and incorporated, so as to enhance recognition and memory of social cues and facilitate approach to positive signals. By contrast, IN-OT led to ignorance of undesirable feedback and, thus, may weaken the influence of undesirable information on subsequent decisionmaking and behavior. Consistently, previous studies showed that OT reduced recognition of and affective responses to negative signals, and failed to change behavior after the receipt of negative information (i.e., social betrayal; ref. 17). Animal studies also reported that OT abolished the impact of negative outcomes (such as traumatic events and aversive conditioning) on subsequent behaviors in rats and mice (57, 58). Our findings suggest a cognitive mechanism underlying such valence-specific OT effects: the facilitation of learning from positive information for subsequent updates and the reduction of learning from negative information.

Research has suggested the engagement of dopamine in optimistic updating (59). Administration of dihydroxy-l-phenylalanine that enhanced dopaminergic function facilitated optimism by impairing updating upon undesirable feedback (59). Although both the oxytocinergic and dopaminergic systems were involved in optimism, the cognitive route each system took to mediate optimism differed remarkably. Enhancing dopaminergic function selectively reduced updating upon undesirable feedback without having an influence on updating upon desirable feedback (59). However, IN-OT increased optimistic updating through both facilitation of updating upon desirable feedback and impairment of updating upon undesirable feedback. Thus, distinct molecular substrates may be engaged in belief updating linked to desirable versus undesirable feedback. Future research should clarify whether and how the oxytocinergic and dopaminergic systems interact to mediate human optimistic updating.

Methods

Ethics Approval.

The experimental procedures were in line with the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the local Research Ethics Committee of the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, Beijing Normal University. Participants provided written informed consent after the experimental procedure had been fully explained and were reminded of their right to withdraw at any time during the study.

Participants.

We recruited 320 male Chinese college students as paid volunteers. Twelve participants (3.75%) were dropped from data analysis because of technical problems or participants’ failure to complete the study. Data from 308 participants were included in the final data analysis: 99 participants in study 1 (50 under PL, 49 under OT), 95 participants in study 2 (47 under PL, 48 under OT), and 114 participants in study 3 (57 under PL, 57 under OT). All participants reported no history of neurological or psychiatric diagnoses. Exclusion criteria were self-reported medical or psychiatric disorder and drug/alcohol abuse. Participants were instructed to refrain from smoking or drinking (except water) for 2 h before the experiment.

Procedure.

All three studies were conducted by following a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, between-subjects design. Participants first completed a set of questionnaires and were then administered with OT or PL and performed the belief updating task 40 min later. The procedure of OT and PL administration was similar to previous work (15–17). A single intranasal dose of 24 IU OT or PL (containing the same ingredients except for the neuropeptide) was self-administrated by nasal spray under experimenter supervision. Finally, participants completed the mood measurement again.

The Belief Update Task.

In studies 1 and 2, participants completed two sessions of life event estimation. Participants were first presented with 40 different adverse life events (SI Appendix, SI Methods) and estimated their likelihood (0–99%) of experiencing each event on a self-paced basis (first Estimate). Participants were then presented with the probability of each event occurring to an average person in a similar environment (Feedback). Five minutes after the first session, participants were invited to complete a second estimation session, in which participants were presented with these 40 events in a random order and estimated the likelihood of each event again (second Estimate). The number of desirable and undesirable trials was reported in SI Appendix, Table S21. After the second session, participants were given a surprise memory test for the presented feedback. The belief update task in study 3 was similar to that in studies 1 and 2, except that, for each event, participants additionally made judgment of (i) confidence in their first and second Estimate; and (ii) acceptance of the presented feedback.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs. M. Crockett, A. Kappes, S. Shamay-Tsoory, and C. Zink for their valuable comments on an early draft; B. Li for OT preparation; and Dr. K. Woodcock for proofreading. This work was supported by startup funding from the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning, IDG/McGovern Institute for Brain Research; Open Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning (Y.M.); Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Z151100003915122) (to Y.M.); National Natural Science Foundation of China Projects 31470986, 31421003, and 91332125; and Ministry of Education of China Project 20130001110049 (to S.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*Weissman AN, Beck AT, Development and Validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A Preliminary Investigation. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, March 27–31, 1978, Toronto.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1604285113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McKay RT, Dennett DC. The evolution of misbelief. Behav Brain Sci. 2009;32(6):493–510, discussion 510–561. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X09990975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharot T. The optimism bias. Curr Biol. 2011;21(23):R941–R945. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter CS. Oxytocin pathways and the evolution of human behavior. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:17–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishak WW, Kahloon M, Fakhry H. Oxytocin role in enhancing well-being: A literature review. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Y, Shamay-Tsoory S, Han S, Zink CF. Oxytocin and social adaptation: Insights from neuroimaging studies of healthy and clinical populations. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20(2):133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domes G, Heinrichs M, Michel A, Berger C, Herpertz SC. Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(6):731–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riem MME, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Voorthuis A, van IJzendoorn MH. Oxytocin effects on mind-reading are moderated by experiences of maternal love withdrawal: An fMRI study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;51:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radke S, de Bruijn ERA. Does oxytocin affect mind-reading? A replication study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartz JA, et al. Oxytocin selectively improves empathic accuracy. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(10):1426–1428. doi: 10.1177/0956797610383439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guastella AJ, Mitchell PB, Mathews F. Oxytocin enhances the encoding of positive social memories in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(3):256–258. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsh AA, Yu HH, Pine DS, Blair RJ. Oxytocin improves specific recognition of positive facial expressions. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;209(3):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1780-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guastella AJ, Mitchell PB, Dadds MR. Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unkelbach C, Guastella AJ, Forgas JP. Oxytocin selectively facilitates recognition of positive sex and relationship words. Psychol Sci. 2008;19(11):1092–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Dreu CKW, et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Science. 2010;328(5984):1408–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.1189047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Y, Liu Y, Rand DG, Heatherton TF, Han S. Opposing oxytocin effects on intergroup cooperative behavior in intuitive and reflective minds. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(10):2379–2387. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature. 2005;435(7042):673–676. doi: 10.1038/nature03701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron. 2008;58(4):639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nave G, Camerer C, McCullough M. Does oxytocin increase trust in humans? A critical review of research. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(6):772–789. doi: 10.1177/1745691615600138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharot T, Korn CW, Dolan RJ. How unrealistic optimism is maintained in the face of reality. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(11):1475–1479. doi: 10.1038/nn.2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korn CW, Sharot T, Walter H, Heekeren HR, Dolan RJ. Depression is related to an absence of optimistically biased belief updating about future life events. Psychol Med. 2014;44(3):579–592. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eil D, Rao JM. The good news-bad news effect: Asymmetric processing of objective information about yourself. Am Econ J Microecon. 2011;3(2):114–138. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choe HK, et al. Oxytocin mediates entrainment of sensory stimuli to social cues of opposing valence. Neuron. 2015;87(1):152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saphire-Bernstein S, Way BM, Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is related to psychological resources. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(37):15118–15122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113137108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacDonald K, et al. Oxytocin and psychotherapy: A pilot study of its physiological, behavioral and subjective effects in males with depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):2831–2843. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercedes Perez-Rodriguez M, Mahon K, Russo M, Ungar AK, Burdick KE. Oxytocin and social cognition in affective and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(2):265–282. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Reed GM, Bower JE, Gruenewald TL. Psychological resources, positive illusions, and health. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):99–109. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor SE, Broffman JI. Psychosocial resources: Functions, origins, and links to mental and physical health. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2011;44:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(6):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vollmann M, Antoniw K, Hartung FM, Renner B. Social support as mediator of the stress buffering effect of optimism: The importance of differentiating the recipients’ and providers’ perspective. Eur J Pers. 2011;25(2):146–154. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersson MA. Dispositional optimism and the emergence of social network diversity. Sociol Q. 2012;53(1):92–115. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruiz JM, Matthews KA, Scheier MF, Schulz R. Does who you marry matter for your health? Influence of patients’ and spouses’ personality on their partners’ psychological well-being following coronary artery bypass surgery. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(2):255–267. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor ZE, et al. Dispositional optimism: A psychological resource for Mexican-origin mothers experiencing economic stress. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26(1):133–139. doi: 10.1037/a0026755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartz JA, Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner KN. Social effects of oxytocin in humans: Context and person matter. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(7):301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvares GA, Chen NTM, Balleine BW, Hickie IB, Guastella AJ. Oxytocin selectively moderates negative cognitive appraisals in high trait anxious males. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(12):2022–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quirin M, Kuhl J, Düsing R. Oxytocin buffers cortisol responses to stress in individuals with impaired emotion regulation abilities. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(6):898–904. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leknes S, et al. Oxytocin enhances pupil dilation and sensitivity to ‘hidden’ emotional expressions. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;8(7):741–749. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puskar KR, Sereika SM, Lamb J, Tusaie-Mumford K, McGuinness T. Optimism and its relationship to depression, coping, anger, and life events in rural adolescents. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1999;20(2):115–130. doi: 10.1080/016128499248709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirsch JK, Walker KL, Chang EC, Lyness JM. Illness burden and symptoms of anxiety in older adults: Optimism and pessimism as moderators. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(10):1614–1621. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lebreton M, Abitbol R, Daunizeau J, Pessiglione M. Automatic integration of confidence in the brain valuation signal. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(8):1159–1167. doi: 10.1038/nn.4064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Martino B, Fleming SM, Garrett N, Dolan RJ. Confidence in value-based choice. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(1):105–110. doi: 10.1038/nn.3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharot T, Garrett N. Forming beliefs: Why valence matters. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma WJ, Jazayeri M. Neural coding of uncertainty and probability. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:205–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults: Manual, Instrument, and Scoring Guide. Mind Garden; Inc., Menlo Park, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garrett N, et al. Losing the rose tinted glasses: Neural substrates of unbiased belief updating in depression. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:639. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palminteri S, et al. Critical roles for anterior insula and dorsal striatum in punishment-based avoidance learning. Neuron. 2012;76(5):998–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vilares I, Howard JD, Fernandes HL, Gottfried JA, Kording KP. Differential representations of prior and likelihood uncertainty in the human brain. Curr Biol. 2012;22(18):1641–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stavropoulos KK, Carver LJ. Research review: Social motivation and oxytocin in autism--implications for joint attention development and intervention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(6):603–618. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shamay-Tsoory SG, Abu-Akel A. The social salience hypothesis of oxytocin. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(3):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Dreu CK. Oxytocin modulates the link between adult attachment and cooperation through reduced betrayal aversion. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(7):871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labuschagne I, et al. Oxytocin attenuates amygdala reactivity to fear in generalized social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2403–2413. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watanabe T, et al. Mitigation of sociocommunicational deficits of autism through oxytocin-induced recovery of medial prefrontal activity: A randomized trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):166–175. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bartz JA, et al. Effects of oxytocin on recollections of maternal care and closeness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(50):21371–21375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012669107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radke S, Roelofs K, de Bruijn ERA. Acting on anger: Social anxiety modulates approach-avoidance tendencies after oxytocin administration. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(8):1573–1578. doi: 10.1177/0956797612472682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varki A. Human uniqueness and the denial of death. Nature. 2009;460(7256):684. doi: 10.1038/460684c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weinstein ND, Klein WM. Resistance of personal risk perceptions to debiasing interventions. Health Psychol. 1995;14(2):132–140. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lukas M, et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin facilitates pro-social behavior and prevents social avoidance in rats and mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(11):2159–2168. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toth I, Neumann ID, Slattery DA. Central administration of oxytocin receptor ligands affects cued fear extinction in rats and mice in a timepoint-dependent manner. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;223(2):149–158. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharot T, Guitart-Masip M, Korn CW, Chowdhury R, Dolan RJ. How dopamine enhances an optimism bias in humans. Curr Biol. 2012;22(16):1477–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.