Significance

Cyanobacterial blooms pose a major threat to the water quality of many eutrophic lakes and reservoirs. Cyanobacteria are thought to be very effective competitors when CO2 levels are depleted during dense blooms. Their response to elevated CO2 is less understood, however. We study competition among cyanobacteria, and find both laboratory and field evidence for natural selection of strains with different carbon uptake systems at different CO2 levels. Our results demonstrate that changes in inorganic carbon availability act as an important selective factor in cyanobacterial communities and suggest that future harmful cyanobacterial blooms will have a genotype composition that differs from contemporary blooms and will be tuned to the high-CO2 conditions.

Keywords: climate change, harmful algal blooms, Microcystis aeruginosa, microevolution, natural selection

Abstract

Rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations are likely to affect many ecosystems worldwide. However, to what extent elevated CO2 will induce evolutionary changes in photosynthetic organisms is still a major open question. Here, we show rapid microevolutionary adaptation of a harmful cyanobacterium to changes in inorganic carbon (Ci) availability. We studied the cyanobacterium Microcystis, a notorious genus that can develop toxic cyanobacterial blooms in many eutrophic lakes and reservoirs worldwide. Microcystis displays genetic variation in the Ci uptake systems BicA and SbtA, where BicA has a low affinity for bicarbonate but high flux rate, and SbtA has a high affinity but low flux rate. Our laboratory competition experiments show that bicA + sbtA genotypes were favored by natural selection at low CO2 levels, but were partially replaced by the bicA genotype at elevated CO2. Similarly, in a eutrophic lake, bicA + sbtA strains were dominant when Ci concentrations were depleted during a dense cyanobacterial bloom, but were replaced by strains with only the high-flux bicA gene when Ci concentrations increased later in the season. Hence, our results provide both laboratory and field evidence that increasing carbon concentrations induce rapid adaptive changes in the genotype composition of harmful cyanobacterial blooms.

Atmospheric CO2 concentrations are predicted to double during this century (1, 2). Species may adapt to elevated CO2 by the sorting of existing genetic variation and the establishment of new beneficial mutations. These evolutionary processes can alter the physiological and ecological response of photosynthetic species to future CO2 levels (3). Several recent laboratory studies have investigated the potential for evolutionary changes in response to rising CO2 concentrations (4–9). For example, selection experiments with the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii revealed that some cell lines grown at elevated CO2 levels for 1,000 generations had obtained a reduced growth rate at ambient CO2, presumably because mutations reduced the effectiveness of CO2 acquisition (4, 5). Other laboratory studies argue that elevated atmospheric CO2 fails to evoke specific evolutionary adaptation in phytoplankton species (7). Thus far, however, the specific genetic and molecular adaptations to rising CO2 favored by natural selection are not well understood. Furthermore, adaptation to changing CO2 conditions has rarely been investigated within complex species assemblages (9) and, to our knowledge, has never been reported from natural waters.

Cyanobacteria produce dense and often toxic blooms in many eutrophic lakes worldwide (10–12), and are likely to benefit from eutrophication and global warming (10, 13–15). Dense cyanobacterial blooms can deplete the dissolved CO2 [CO2(aq)] concentration (16–18), which provides an opportunity to study adaptation to changes in carbon availability. Cyanobacteria are often thought to be superior competitors when CO2(aq) concentrations are depleted, because they use a very effective CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) (19, 20). The cyanobacterial CCM is based on the uptake of CO2 and bicarbonate, and subsequent accumulation of inorganic carbon (Ci) in specialized compartments, called carboxysomes, for CO2 fixation by the enzyme RuBisCO (21). Five Ci uptake systems are known in cyanobacteria. Two CO2 uptake systems and the ATP-dependent bicarbonate transporter BCT1 are present in most freshwater cyanobacteria (15, 21–23). Two other bicarbonate uptake systems, BicA and SbtA, are less widespread. Both are sodium-dependent symporters, but BicA has a low affinity for bicarbonate and high flux rate, whereas SbtA has a high affinity and low flux rate (21, 24). Affinity refers here to the effectiveness of bicarbonate uptake at low bicarbonate concentrations, whereas the flux rate refers to the bicarbonate uptake rate at high bicarbonate concentrations.

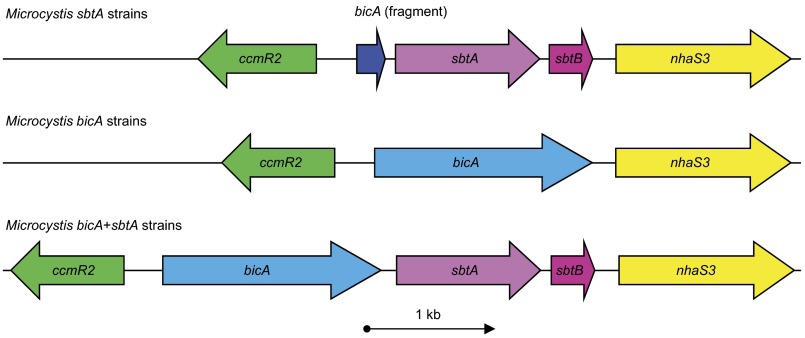

We recently compared CCM gene sequences of 20 strains of Microcystis (23), a ubiquitous cyanobacterium that can produce a potent family of hepatotoxins known as microcystins (25). The strains were very similar in their CCM gene composition, but interestingly some strains lacked the high-flux bicarbonate uptake gene bicA, whereas others lacked the high-affinity bicarbonate uptake gene sbtA. Hence, three different Ci uptake genotypes can be distinguished (23): sbtA strains (with sbtA but no or incomplete bicA), bicA strains (with bicA but no sbtA), and bicA + sbtA strains (Fig. 1). The three genotypes produce different phenotypes. Laboratory experiments showed that the growth rate of the sbtA genotype is reduced at high Ci levels, the bicA genotype has reduced growth at low Ci levels, whereas the bicA + sbtA genotype maintains a constant growth rate across a wide range of Ci levels (23). Little is known, however, about the occurrence of these three Ci uptake genotypes in lakes, and how their relative frequencies may change in response to increasing Ci concentrations. Here, we test the potential for adaptive microevolution of Microcystis in response to elevated CO2, by investigating changes in the relative frequencies of the different Ci uptake genotypes in laboratory competition experiments and a lake study.

Fig. 1.

The three Ci uptake genotypes of Microcystis. The variable genomic regions contain the transcriptional regulator gene ccmR2, the sodium-dependent bicarbonate uptake genes bicA and sbtA, a posttranslation regulator gene of SbtA known as sbtB, and the sodium/proton antiporter gene nhaS3.

Results

Competition Experiments.

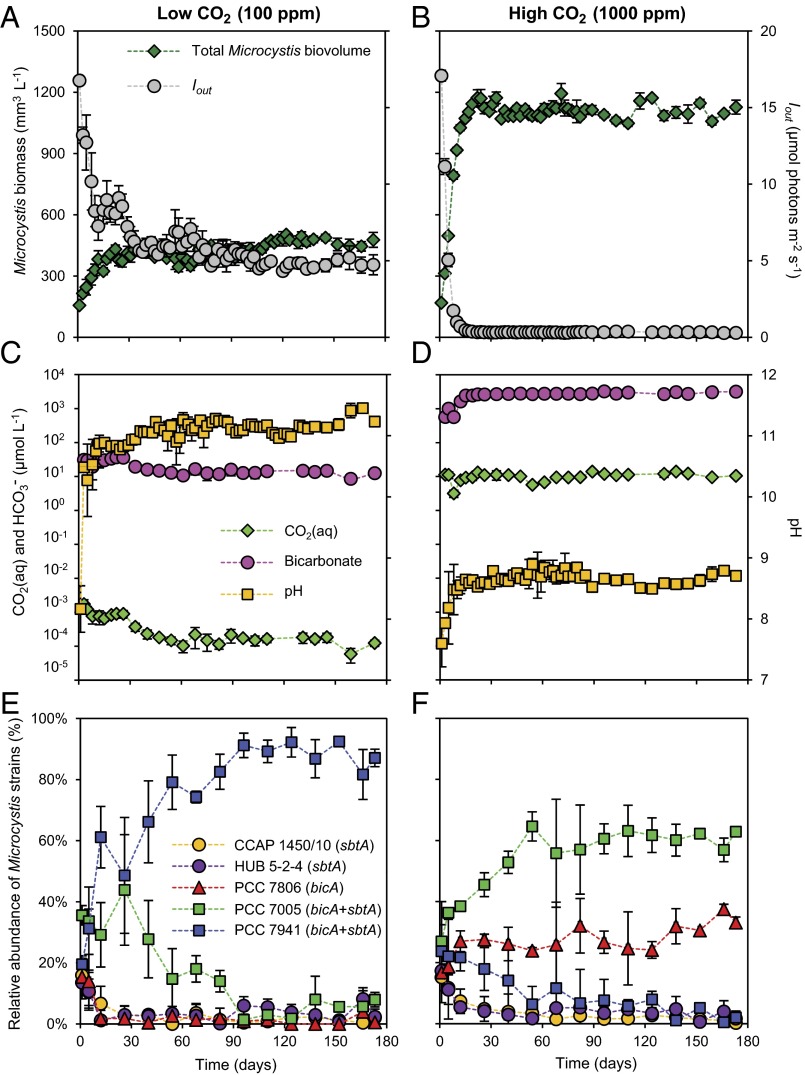

We ran competition experiments in three chemostats at low CO2 (100 ppm) and three chemostats at high CO2 (1,000 ppm) levels. Each chemostat was inoculated with five Microcystis strains, including two sbtA strains (CCAP 1450/10 and HUB 5-2-4), one bicA strain (PCC 7806) and two bicA + sbtA strains (PCC 7005 and PCC 7941) (SI Appendix, Table S1). Four strains produced the hepatotoxin microcystin, whereas PCC 7005 was the only nontoxic strain. In the low CO2 chemostats, the total Microcystis biomass increased until a steady state was reached, at which the CO2(aq) and bicarbonate concentration were depleted to 1.5 × 10−4 μmol⋅L−1 and 15 μmol⋅L−1, respectively, and pH increased to 11.2 (Fig. 2 A and C). The high CO2 chemostats produced a 2.5-fold higher Microcystis biomass, with much higher steady-state CO2(aq) and bicarbonate concentrations of 10 μmol⋅L−1 and 2,700 μmol⋅L−1, respectively, and a lower pH of 8.8 (Fig. 2 B and D).

Fig. 2.

Laboratory competition experiments with five Microcystis strains at low and high CO2 levels. (Left) Low CO2 chemostats. (Right) High CO2 chemostats. (A and B) Microcystis biomass (expressed as biovolume) and the light intensity Iout transmitted through the chemostats. (C and D) Concentrations of dissolved CO2 [CO2(aq)] and bicarbonate, and pH. (E and F) Relative abundances of the five Microcystis strains. The data points show the mean values (±SD) of three replicated chemostat experiments.

In the low CO2 chemostats, the toxic bicA + sbtA strain PCC 7941 competitively replaced the two sbtA strains, the bicA strain, and the nontoxic bicA + sbtA strain, and comprised ∼90% of the total Microcystis population at steady state (Fig. 2E). In contrast, in the high CO2 chemostats, the nontoxic bicA + sbtA strain PCC 7005 coexisted with the toxic bicA strain PCC 7806, with relative abundances of ∼60% and ∼30%, respectively, at steady state (Fig. 2F). Selection coefficients, calculated from the replacement rates of the strains and their generation times, ranged from 0.16 to 0.62 in the low CO2 chemostats and from 0.08 to 0.20 in the high CO2 chemostats (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S2).

Lake Study.

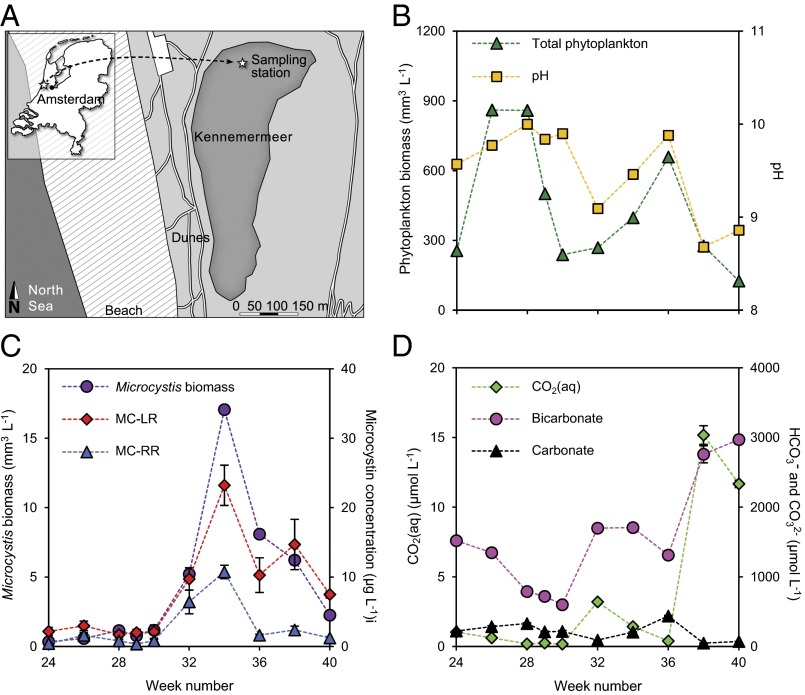

Our field study was carried out in Lake Kennemermeer, a slightly brackish coastal dune lake in The Netherlands, in summer and autumn of 2013 (Fig. 3A). Water temperature was 20–23 °C in summer, and then gradually declined to 11 °C in early autumn (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The lake contained high phytoplankton abundances, with particularly dense blooms in weeks 26–28 and week 36 (Fig. 3B). The phytoplankton community consisted largely of cyanobacteria (>95% of the total biovolume), including Pseudanabaenaceae, small Chroococcales, Anabaenopsis hungarica and Microcystis spp. The Microcystis population was dominated by potentially toxic genotypes containing the microcystin synthetase gene mcyB (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Concentrations of Microcystis and the two dominant microcystin types, MC-LR and MC-RR, peaked in week 34 (Fig. 3C). The MC-LR concentration (up to 23.2 µg⋅L−1) exceeded the provisional guideline for safe drinking water (1 µg⋅L−1) of the World Health Organization and common guidelines for recreational waters (26), justifying closure of the lake for recreation.

Fig. 3.

Phytoplankton biomass and inorganic carbon speciation in Lake Kennemermeer. (A) Map of Lake Kennemermeer with the sampling station. (B) Total phytoplankton biomass (expressed as biovolume) and pH. (C) Microcystis biomass (expressed as biovolume) and concentrations of the two most abundant microcystin variants (MC-LR and MC-RR). (D) Concentrations of CO2(aq), bicarbonate, and carbonate. Data points represent the mean (±SD) of three replicate measurements; error bars that are not visible do not exceed the size of the symbols.

In summer, CO2(aq) concentrations in the lake were reduced below 3.5 µmol⋅L−1 and were strongly depleted to <0.4 µmol⋅L−1 in weeks 28–30 and week 36 (Fig. 3D). When phytoplankton abundance decreased in autumn, the CO2(aq) concentration increased to ∼15 µmol⋅L−1, equilibrating with the atmospheric pCO2 levels (390 ppm). CO2 depletion during the summer bloom led to a strong increase in pH, with values up to ∼10 during the two peaks in phytoplankton abundance (Fig. 3B) (Pearson correlation of pH vs. log CO2: r = −0.98, n = 10, P < 0.001). At pH between 8 and 10, bicarbonate is the dominant Ci species. Bicarbonate concentrations showed similar temporal dynamics as the CO2(aq) concentration, with relatively low bicarbonate concentrations during the summer blooms and higher concentrations in autumn (Fig. 3D) [Pearson correlation of CO2(aq) vs. bicarbonate: r = 0.90, n = 10, P < 0.001]. The sodium concentration in the lake (measured in week 29) was 12.7 ± 0.4 mmol⋅L−1, which allows maximum or near-maximum activity of the sodium-dependent bicarbonate transporters BicA and SbtA, because both transporters have half-saturation constants of 1–2 mmol⋅L−1 sodium (24, 27).

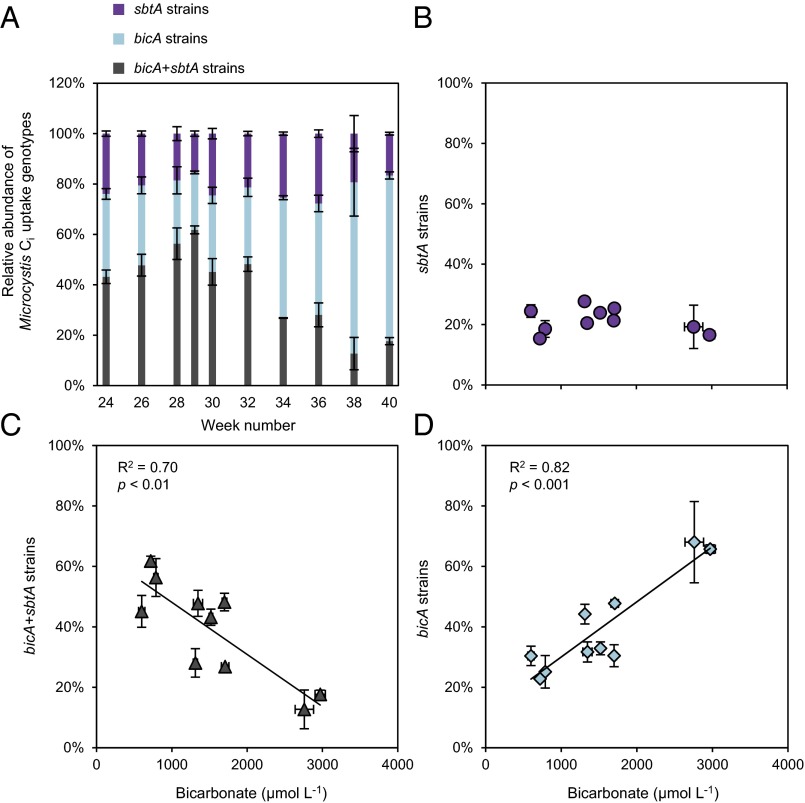

All three Ci uptake genotypes of Microcystis were present in the lake (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Tables S3 and S4), but their relative abundances changed during the study period (Fig. 4A). The sbtA strains represented ∼20% of the Microcystis population during the entire season (Fig. 4B). The bicA + sbtA strains dominated the Microcystis population in weeks 24–32, especially during the strong CO2 depletion in weeks 28–29, but were largely replaced by bicA strains in late summer and autumn when Ci concentrations in the lake increased. Relative abundances of the bicA + sbtA strains were negatively correlated with the bicarbonate concentration (Fig. 4C) (Pearson correlation: r = −0.84, n = 10, P < 0.01), whereas those of the bicA strains were positively correlated with bicarbonate (Fig. 4D) (Pearson correlation: r = 0.91, n = 10, P < 0.001). Replacement of bicA + sbtA strains by bicA strains occurred in ∼2 months. With a generation time of 1.5–5.2 d (28), this corresponds to 12–42 generations and a selection coefficient of 0.06–0.19 per generation, which is comparable to the selection coefficients in the chemostats (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Table S2).

Fig. 4.

Ci uptake genotypes of Microcystis in the lake study. (A) Relative abundances of the three Ci uptake genotypes (sbtA strains, bicA strains, and bicA + sbtA strains). (B–D) Relation between the relative abundances of the Ci uptake genotypes and the bicarbonate concentration. The data points show the mean (±SD) of three replicate measurements. The trend lines are based on linear regression (n = 10).

Discussion

Our laboratory competition experiments and lake study show qualitatively similar changes in strain composition. In both systems, the Microcystis population was dominated by bicA + sbtA strains at low Ci levels that were (partly) replaced by bicA strains at high Ci levels (Figs. 2 and 4). Previous studies have shown that the high-affinity but low-flux bicarbonate uptake system SbtA is more effective at low bicarbonate concentrations, whereas the low-affinity but high-flux enzyme BicA is more effective at high bicarbonate concentrations (23, 24). Hence, the trade-off between affinity and flux rate offers a likely explanation for the observed shift in strain composition. In particular, with increasing CO2 and bicarbonate concentrations, high-affinity bicarbonate uptake systems are no longer needed. We note that in bicA + sbtA strains of Microcystis, bicA and sbtA are located on the same operon and hence are cotranscribed (23). Superfluous transcription of sbtA or posttranscriptional down-regulation of the SbtA enzyme, for example by SbtB (27), will be costly when SbtA cannot be efficiently used, which will disfavor bicA + sbtA strains at high bicarbonate concentrations. Our results thus provide both laboratory and field evidence demonstrating that bicA strains; that is, strains with low-affinity but high-flux bicarbonate uptake systems, have a selective advantage at high Ci availability.

In addition to bicarbonate uptake systems, cyanobacteria also deploy two intracellular CO2 “uptake” systems, which convert CO2 passively diffusing into the cell into bicarbonate (21, 29, 30). In all Microcystis strains investigated so far, both CO2 uptake systems were present (23) and the genes encoding these two CO2 uptake systems were constitutively expressed (31–33). A possible explanation might be that the sustained activity of both intracellular CO2 uptake systems helps to maintain a low CO2(aq) concentration in the cytoplasm, thus maximizing the diffusive influx of CO2. Bloom-forming cyanobacteria like Microcystis usually occur in mildly to highly alkaline waters (pH > 7.5), where bicarbonate concentrations are much higher than the CO2(aq) concentration (Fig. 3D). Laboratory studies have shown that the high-affinity bicarbonate uptake system BCT ceases its activity, whereas the BicA enzyme remains active at elevated CO2 levels (31, 32), and that bicarbonate still accounts for most of the Ci uptake even at elevated CO2 levels (34–36). Hence, in alkaline waters, adaptation of the bicarbonate uptake systems to changes in Ci availability is indeed likely to have major fitness consequences.

Quantitatively, bicA strains responded more strongly to increasing Ci concentrations in the lake than in the chemostat experiments, whereas sbtA strains persisted in the lake but were competitively excluded from the chemostats. These dissimilarities might be attributed to differences in environmental conditions between lakes and laboratory experiments. For example, the chemostat experiments used continuous illumination, whereas Microcystis in Lake Kennemermeer experienced large daily fluctuations in both light conditions and inorganic carbon concentrations, which induced diel variation in expression of the bicarbonate uptake genes and several other CCM genes (33). Furthermore, the chemostats applied homogeneous mixing to single-celled Microcystis populations, whereas Microcystis often develops multicellular colonies migrating vertically in stagnant lakes (37). Microcystis is also known to survive prolonged burial in lake sediments, after which it can be resuspended in the water column (38). Both spatiotemporal heterogeneity and reseeding from the sediments tend to promote diversity, and may explain the observed co-occurrence of all three Ci uptake genotypes in the lake.

Some of our results may also be due to further variation among Microcystis strains other than their Ci uptake genes (39, 40). For instance, the strains in our selection experiments differed in the production of microcystin. In addition to its toxicity to humans and mammals, microcystin can also bind to cyanobacterial proteins such as the RuBisCO enzyme to offer protection against oxidative stress (41). Carbon-limited conditions are likely to induce more oxidative stress than elevated CO2 concentrations, which may explain why the microcystin-producing bicA + sbtA strain PCC 7941 performed better at 100 ppm CO2, whereas the nonmicrocystin-producing bicA + sbtA strain PCC 7005 performed better at 1,000 ppm (Fig. 2). Our lake study, however, did not show a relation between the relative abundance of microcystin-producing strains and the Ci concentrations (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C), indicating that selection among the different Ci uptake genotypes played a much larger role in the adaptation to changing Ci concentrations than genetic variation in microcystin production.

Our results add to the growing literature showing that plankton species are capable of rapid evolutionary adaptation to changing conditions; for example, in response to rising CO2 levels (6, 8, 9), increasing temperature (42, 43), and changes in predation pressure (44, 45). A key advance of the present work is that the adaptive changes could be linked to specific genetic and molecular traits, which enabled monitoring of natural selection not only in confined laboratory experiments but also in lakes. In our study, and several previous studies (6, 42–45), the adaptive changes are most likely caused by sorting of existing genetic variation rather than by de novo mutations. This implies that at the time scale of cyanobacterial bloom development, the traits (in this case, the Ci uptake kinetics) of cyanobacterial species may change due to a reshuffling of the relative abundances of different genotypes within the species. Hence, predictions of harmful algal bloom development cannot be based on the assumption that species traits remain constant. Instead, an ecoevolutionary approach will be required (46–48), in which traits evolve in response to changes in environmental conditions that, in the case of CO2 depletion, are at least partly induced by the phytoplankton blooms themselves.

In conclusion, our study shows that changes in Ci availability act as an important selective factor in cyanobacterial communities. Some strains perform better at low Ci concentrations, whereas other strains are better competitors at high Ci levels, causing a succession of different Ci uptake genotypes during bloom development. Models and laboratory experiments predict that rising atmospheric CO2 levels will lead to higher CO2(aq) and bicarbonate concentrations, and a later onset and shorter duration of CO2-depleted conditions during dense summer blooms (14, 15). Our results suggest that this increased Ci availability will favor low-affinity but high-flux bicarbonate uptake genotypes. Hence, future harmful cyanobacterial blooms will most likely have a genotype composition that differs from contemporary blooms and will be adapted to the new conditions in a high-CO2 world.

Materials and Methods

Competition Experiments.

Competition experiments were conducted in CO2-controlled chemostats designed specifically for phytoplankton studies (14, 31, 49). The chemostats consisted of flat culture vessels with an optical path length of 5 cm and an effective working volume of 1.8 L. The chemostats were illuminated from one side at a constant incident irradiance of Iin = 40 μmol photons·m−2⋅s−1 using white fluorescent tubes (Philips Master TL-D 90 De Luxe 18 W/965; Philips Lighting). The chemostats were maintained at a constant temperature of 25 °C, using a nutrient-rich mineral medium without (bi)carbonate salts, and aerated with small gas bubbles containing either 100 or 1,000 ppm CO2 at a flow rate of 30 L⋅h−1 (31). The chemostats were run at a dilution rate of 0.2 d−1.

Microcystis strains CCAP 1450/10, HUB 5-2-4, PCC 7806, PCC 7005, and PCC 7941 (SI Appendix, Table S1) were precultured in monoculture chemostats at 400 ppm CO2. Subsequently, six chemostats were each inoculated with the five precultured strains mixed at equal initial abundances and a total initial Microcystis biovolume of ∼160 mm3⋅L−1. Three chemostats were exposed to 100 ppm pCO2 (“low CO2”) and the three other chemostats to 1,000 ppm pCO2 (“high CO2”). The chemostats were run for a total of 175 d and were sampled one to three times per week for further analysis. Cell numbers, biovolumes, light conditions, and pH were measured as described before (31).

Lake Study.

Lake Kennemermeer (52°27′18.5′′N, 4°33′48.6′′E) is a shallow coastal dune lake located northwest of Amsterdam, The Netherlands, close to the North Sea (Fig. 2A). The lake is not an official swimming location, because of yearly recurrent problems caused by dense harmful cyanobacterial blooms. The lake has a maximum depth of ∼1 m and a surface area of ∼0.1 km2. The lake is well mixed by wind throughout the year.

From June to October 2013, we sampled the lake two to three times per month, always at 10:30 AM, at a fixed location at the north side using a small boat. Aliquots of lake water (three replicates of 5 L each) were collected 0.2 m below the surface and processed immediately on land. A hydrolab surveyor and Datasonde 4a (OTT Hydromet) measured temperature and pH at 0.2-m depth. Phytoplankton cells were preserved with Lugol’s iodine for microscopic analysis (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods).

Chemical Analyses.

Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and sodium concentrations were measured in filtered supernatant of the chemostat and lake samples. CO2(aq), bicarbonate, and carbonate concentrations were calculated from DIC, pH, and temperature (SI Appendix, Table S5). Microcystins were extracted from filtered cells with 75% MeOH and analyzed by HPLC (49). See SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods for details.

Analysis of Genotype Composition.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from chemostat samples and lake samples that were filtered on-site, using spin column DNA extraction kits (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods).

We first investigated whether all three Microcystis Ci uptake genotypes were present in purified gDNA lake samples, using PCR reactions with the GoTaq Hot Start Polymerase kit (Promega) according to the supplier’s instructions (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods). The Microcystis-specific primers used for this purpose are listed in SI Appendix, Table S3.

Subsequently, qPCR reactions were applied to purified gDNA to quantify the relative abundances of the different genotypes in the chemostat and lake samples (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods). For this purpose, we designed gene-specific primers to target the 16S rRNA gene, rbcX, bicA, sbtA, bicA + sbtA, mcyB, and isiA (SI Appendix, Table S3), using gDNA from axenic laboratory strains as reference samples. LinRegPCR software (v2012.3) was used for baseline correction, calculation of Cq values, and calculation of the amplification efficiency of individual runs (SI Appendix, Table S3). Relative ratios of the numbers of gene copies were calculated according to the comparative CT method (50). The qPCR analysis was validated using defined mixtures of isolated Microcystis strains (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Because our field data set was limited to one lake sampled during one summer, we did not attempt to separate the statistical effects of many environmental variables on the genotype assemblage. Instead, we applied simple correlation analyses to describe relationships between the relative frequencies of the Ci uptake genotypes and the Ci concentration. The rate of replacement was estimated from the slope of the linear regression of ln(x1/x2) versus time (51, 52), where x1 and x2 are the relative frequencies of two genotypes. The selection coefficient was calculated by scaling the replacement rate to the generation time (51). The generation time in the chemostats was calculated as td = ln(2)/µ, where µ is the growth rate of the total Microcystis population (taking into account the dilution rate).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to the memory of our dear colleague and coauthor Hans C.P. Matthijs, one of the pioneers of cyanobacterial photosynthesis. We thank Cathleen Broersma for assistance with the laboratory competition experiments; Bas van Beusekom and Hélène Thuret for support with lake sampling; Leo Hoitinga for assistance with the dissolved inorganic carbon measurements; Dennis Jakupovic for assistance with the gDNA extractions; and Jan van Arkel for drawing the map of Lake Kennemermeer. This research was supported by the Division of Earth and Life Sciences of The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. J.M.S. acknowledges support by the BE-BASIC Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1602435113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Solomon S, et al., editors. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2007. Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meinshausen M, et al. The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Clim Change. 2011;109(1–2):213–241. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raven JA, Giordano M, Beardall J, Maberly SC. Algal evolution in relation to atmospheric CO2: Carboxylases, carbon-concentrating mechanisms and carbon oxidation cycles. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367(1588):493–507. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins S, Bell G. Phenotypic consequences of 1,000 generations of selection at elevated CO2 in a green alga. Nature. 2004;431(7008):566–569. doi: 10.1038/nature02945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins S, Sültemeyer D, Bell G. Changes in C uptake in populations of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii selected at high CO2. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29(9):1812–1819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohbeck KT, Riebesell U, Reusch TBH. Adaptive evolution of a key phytoplankton species to ocean acidification. Nat Geosci. 2012;5(5):346–351. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low-Décarie E, Jewell MD, Fussmann GF, Bell G. Long-term culture at elevated atmospheric CO2 fails to evoke specific adaptation in seven freshwater phytoplankton species. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;280(1754):20122598. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchins DA, et al. Irreversibly increased nitrogen fixation in Trichodesmium experimentally adapted to elevated carbon dioxide. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8155. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheinin M, Riebesell U, Rynearson TA, Lohbeck KT, Collins S. Experimental evolution gone wild. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12(106):20150056. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paerl HW, Huisman J. Blooms like it hot. Science. 2008;320(5872):57–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1155398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin B, et al. A drinking water crisis in Lake Taihu, China: Linkage to climatic variability and lake management. Environ Manage. 2010;45(1):105–112. doi: 10.1007/s00267-009-9393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michalak AM, et al. Record-setting algal bloom in Lake Erie caused by agricultural and meteorological trends consistent with expected future conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(16):6448–6452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216006110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neil JM, Davis TW, Burford MA, Gobler CJ. The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: The potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae. 2012;14:313–334. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verspagen JMH, et al. Rising CO2 levels will intensify phytoplankton blooms in eutrophic and hypertrophic lakes. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visser PM, et al. How rising CO2 and global warming may stimulate harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Harmful Algae. 2016;54:145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibelings BW, Maberly SC. Photoinhibition and the availability of inorganic carbon restrict photosynthesis by surface blooms of cyanobacteria. Limnol Oceanogr. 1998;43(3):408–419. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balmer MB, Downing JA. Carbon dioxide concentrations in eutrophic lakes: Undersaturation implies atmospheric uptake. Inland Waters. 2011;1(2):125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu B, Schelske CL, Coveney MF. Low carbon dioxide partial pressure in a productive subtropical lake. Aquat Sci. 2011;73(3):317–330. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro J. The role of carbon dioxide in the initiation and maintenance of blue-green dominance in lakes. Freshw Biol. 1997;37(2):307–323. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low-Décarie E, Fussmann GF, Bell G. The effect of elevated CO2 on growth and competition in experimental phytoplankton communities. Glob Change Biol. 2011;17(8):2525–2535. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price GD. Inorganic carbon transporters of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. Photosynth Res. 2011;109(1–3):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s11120-010-9608-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rae BD, Förster B, Badger MR, Price GD. The CO2-concentrating mechanism of Synechococcus WH5701 is composed of native and horizontally-acquired components. Photosynth Res. 2011;109(1–3):59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11120-011-9641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandrini G, Matthijs HCP, Verspagen JMH, Muyzer G, Huisman J. Genetic diversity of inorganic carbon uptake systems causes variation in CO2 response of the cyanobacterium Microcystis. ISME J. 2014;8(3):589–600. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price GD, Woodger FJ, Badger MR, Howitt SM, Tucker L. Identification of a SulP-type bicarbonate transporter in marine cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(52):18228–18233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405211101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Codd GA, Morrison LF, Metcalf JS. Cyanobacterial toxins: Risk management for health protection. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;203(3):264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibelings BW, Backer LC, Kardinaal WEA, Chorus I. Current approaches to cyanotoxin risk assessment and risk management around the globe. Harmful Algae. 2015;49:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du J, Förster B, Rourke L, Howitt SM, Price GD. Characterisation of cyanobacterial bicarbonate transporters in E. coli shows that SbtA homologs are functional in this heterologous expression system. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson AE, Sarnelle O, Tillmanns AR. Effects of cyanobacterial toxicity and morphology on the population growth of freshwater zooplankton: Meta‐analyses of laboratory experiments. Limnol Oceanogr. 2006;51(4):1915–1924. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tchernov D, et al. Passive entry of CO2 and its energy-dependent intracellular conversion to HCO3- in cyanobacteria are driven by a photosystem I-generated ΔμH+ J Biol Chem. 2001;276(26):23450–23455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda S, Badger MR, Price GD. Novel gene products associated with NdhD3/D4-containing NDH-1 complexes are involved in photosynthetic CO2 hydration in the cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43(2):425–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandrini G, Cunsolo S, Schuurmans JM, Matthijs HCP, Huisman J. Changes in gene expression, cell physiology and toxicity of the harmful cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa at elevated CO2. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:401. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandrini G, Jakupovic D, Matthijs HCP, Huisman J. Strains of the harmful cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa differ in gene expression and activity of inorganic carbon uptake systems at elevated CO2 levels. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(22):7730–7739. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02295-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandrini G, et al. Diel variation in gene expression of the CO2-concentrating mechanism during a harmful cyanobacterial bloom. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:551. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sültemeyer D, Price GD, Yu JW, Badger MR. Characterisation of carbon dioxide and bicarbonate transport during steady-state photosynthesis in the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus strain PCC7002. Planta. 1995;197:597–607. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benschop JJ, Badger MR, Dean Price G. Characterisation of CO2 and HCO3- uptake in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Photosynth Res. 2003;77(2–3):117–126. doi: 10.1023/A:1025850230977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eichner M, Thoms S, Kranz SA, Rost B. Cellular inorganic carbon fluxes in Trichodesmium: A combined approach using measurements and modelling. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(3):749–759. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visser PM, Passarge J, Mur LR. Modelling vertical migration of the cyanobacterium Microcystis. Hydrobiologia. 1997;349(1):99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verspagen JMH, et al. Recruitment of benthic Microcystis (Cyanophyceae) to the water column: Internal buoyancy changes or resuspension? J Phycol. 2004;40(2):260–270. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humbert JF, et al. A tribute to disorder in the genome of the bloom-forming freshwater cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harke MJ, et al. A review of the global ecology, genomics, and biogeography of the toxic cyanobacterium, Microcystis spp. Harmful Algae. 2016;54:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zilliges Y, et al. The cyanobacterial hepatotoxin microcystin binds to proteins and increases the fitness of microcystis under oxidative stress conditions. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geerts AN, et al. Rapid evolution of thermal tolerance in the water flea Daphnia. Nat Clim Chang. 2015;5(7):665–668. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Padfield D, Yvon-Durocher G, Buckling A, Jennings S, Yvon-Durocher G. Rapid evolution of metabolic traits explains thermal adaptation in phytoplankton. Ecol Lett. 2015;19(2):133–142. doi: 10.1111/ele.12545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida T, Jones LE, Ellner SP, Fussmann GF, Hairston NG., Jr Rapid evolution drives ecological dynamics in a predator-prey system. Nature. 2003;424(6946):303–306. doi: 10.1038/nature01767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyer JR, Ellner SP, Hairston NG, Jr, Jones LE, Yoshida T. Prey evolution on the time scale of predator-prey dynamics revealed by allele-specific quantitative PCR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(28):10690–10695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600434103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hairston NG, Ellner SP, Geber MA, Yoshida T, Fox JA. Rapid evolution and the convergence of ecological and evolutionary time. Ecol Lett. 2005;8(10):1114–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buckling A, Craig Maclean R, Brockhurst MA, Colegrave N. The Beagle in a bottle. Nature. 2009;457(7231):824–829. doi: 10.1038/nature07892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoener TW. The newest synthesis: Understanding the interplay of evolutionary and ecological dynamics. Science. 2011;331(6016):426–429. doi: 10.1126/science.1193954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van de Waal DB, et al. Reversal in competitive dominance of a toxic versus non-toxic cyanobacterium in response to rising CO2. ISME J. 2011;5(9):1438–1450. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔC(T) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dykhuizen DE, Hartl DL. Selection in chemostats. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47(2):150–168. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.2.150-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Passarge J, Hol S, Escher M, Huisman J. Competition for nutrients and light: Stable coexistence, alternative stable states, or competitive exclusion? Ecol Monogr. 2006;76(1):57–72. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.