Significance

Upon infection, circulating leukocytes leave the bloodstream and migrate into the inflammatory site. Neutrophils are the first leukocytes to be recruited within a few hours, followed by inflammatory lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)-positive monocytes. This study refines the model of the leukocyte recruitment cascade. We demonstrate that upon Toll-like receptor 7/8-mediated vascular inflammation, platelet activation drives the rapid mobilization of Ly6Clow monocytes to the luminal side of the endothelium. Accumulated Ly6Clow monocytes do not extravasate into the tissue. Instead, they meticulously patrol the endothelium and control the subsequent recruitment of neutrophils. Moreover, we show that endothelium-bound cyteine-rich protein 61 (CYR61)/CYR61 connective tissue growth factor nephroblastoma overexpressed 1 (CCN1) protein provides a molecular support for adequate patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state and under inflammatory conditions.

Keywords: inflammation, CCN1, monocyte, neutrophil, platelet

Abstract

Inflammation is characterized by the recruitment of leukocytes from the bloodstream. The rapid arrival of neutrophils is followed by a wave of inflammatory lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)-positive monocytes. In contrast Ly6Clow monocytes survey the endothelium in the steady state, but their role in inflammation is still unclear. Here, using confocal intravital microscopy, we show that upon Toll-like receptor 7/8 (TLR7/8)-mediated inflammation of mesenteric veins, platelet activation drives the rapid mobilization of Ly6Clow monocytes to the luminal side of the endothelium. After repeatedly interacting with platelets, Ly6Clow monocytes commit to a meticulous patrolling of the endothelial wall and orchestrate the subsequent arrival and extravasation of neutrophils through the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. At a molecular level, we show that cysteine-rich protein 61 (CYR61)/CYR61 connective tissue growth factor nephroblastoma overexpressed 1 (CCN1) protein is released by activated platelets and enables the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes upon vascular inflammation. In addition endothelium-bound CCN1 sustains the adequate patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes both in the steady state and under inflammatory conditions. Blocking CCN1 or platelets with specific antibodies impaired the early arrival of Ly6Clow monocytes and abolished the recruitment of neutrophils. These results refine the leukocyte recruitment cascade model by introducing endothelium-bound CCN1 as an inflammation mediator and by demonstrating a role for platelets and patrolling Ly6Clow monocytes in acute vascular inflammation.

Upon infection or tissue injury, circulating leukocytes leave the bloodstream and migrate into the inflammatory site. One determining parameter is the luminal side of the vascular endothelium, which locally presents stimulating molecules to establish adhesive contacts with leukocytes and promote their intravascular crawling and extravasation into the tissue. Neutrophils are typically the first leukocytes to be recruited to an inflammatory site, within a few hours, followed by the arrival of inflammatory monocytes (1, 2).

Two phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets of blood monocytes have been defined in mice according to the cell-surface markers they present. The first group is known as “lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)-positive monocytes” (Ly6C+ monocytes) because they express high levels of Ly6C+, but they also express CX3CR1, CCR2, and CD62L. These Ly6C+ monocytes are called “inflammatory” monocytes because they are recruited to sites of inflammation. The other group comprises the Ly6Clow monocytes which express higher levels of CX3CR1 and lack CCR2 and CD62L. These Ly6Clow cells are termed “patrolling” monocytes (3–5). Ly6C+ monocytes functionally resemble human CD14+ monocytes, whereas the Ly6Clow monocytes are homologs of the human CD14dimCD16+ subset (6). Ly6C+ monocytes are selectively recruited to inflamed tissues (3). They produce high levels of proinflammatory cytokines and differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells in several infectious disease models as well as in atherosclerosis (3, 7, 8). In contrast, the main characteristics of Ly6Clow monocytes are their ability to patrol along the endothelium of blood vessels in the steady state, independently of the direction of the blood flow, and to scavenge microparticles attached to the endothelium (6, 9, 10), acting as luminal blood macrophages (11). Ly6Clow monocytes exhibit anti-inflammatory properties, as evidenced in the ApoE−/− and ldlr−/− mouse models of atherosclerosis (12, 13). They are also proinflammatory, as their number is increased in lupus patients and animal models (6, 14).

Cysteine-rich protein 61 (CYR61)/CYR61 connective tissue growth factor nephroblastoma overexpressed 1 (CCN1) is a matricellular protein produced and secreted by endothelial cells and fibroblasts, among others (15). First described in cardiovascular development and carcinogenesis, CCN1 now is recognized as a mediator in leukocyte migration and inflammatory processes (15, 16) and in the development of the thymus (17). CCN1 exhibits chemoattractant properties for human and murine inflammatory monocytes by promoting their adhesion and migration through integrin CD11b and the cell-surface heparin sulfate proteoglycan syndecan-4 (15, 16, 18–21). CCN1 treatment of murine macrophages induces transcriptional changes characteristic of M1 polarization including the up-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, or IL-6 (21). In addition, CCN1 is up-regulated in response to bacterial or viral infections in vitro and in atherosclerotic lesions in both humans and mice (15, 16) and is released from activated platelets in experimentally induced sepsis (22, 23).

To date, the functions of CYR61/CCN1 in inflammation have been elusive, notably because of the embryonic lethality of Ccn1-null mice, which have impaired vascular integrity and dysfunctional cardiovascular development (24). The chemoattractant properties of CCN1 and its ability to bind to monocytes through CD11b led us to examine the role of endothelium-bound CCN1 on the functions of Ly6Clow monocytes in a steady state and under inflammatory conditions. In this paper we demonstrate that platelets and the luminal meticulous patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes are important in the initiation of Toll-like receptor 7/8 (TLR7/8)-mediated inflammation and in the recruitment of neutrophils. We also show that CCN1/CYR61 protein is released by platelets and acts as a chemoattractant for Ly6Clow monocytes. Moreover endothelium-bound CCN1 is required for adequate patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state and under inflammatory conditions. Collectively, our data refine the model of the leukocyte recruitment cascade.

Results

Endothelium-Bound CCN1 Sustains Patrolling of Ly6Clow Monocytes in the Steady State.

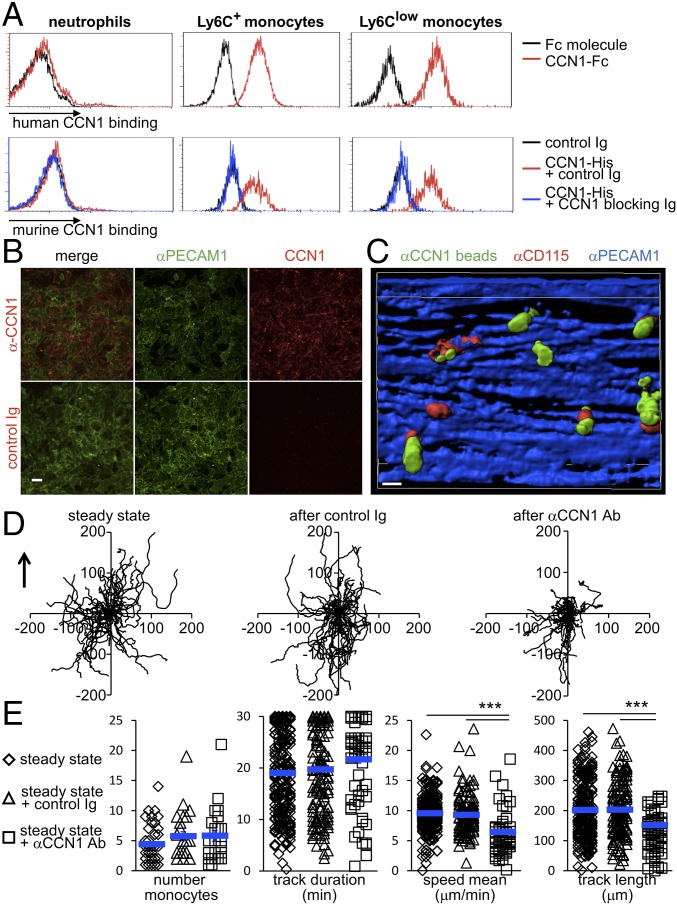

CYR61/CCN1 binds to several leukocytes, and in particular to inflammatory monocytes and macrophages, via integrin CD11b (18, 20, 25). However, the effect of CCN1 on the functions of Ly6Clow monocytes has not been investigated so far. We first examined the binding of CCN1 to Ly6Clow monocytes. We observed that recombinant human CCN1-Fc binds to both Ly6Clow and Ly6C+ murine monocytes but not to neutrophils (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). Identical results were obtained with recombinant murine CCN1-His. Importantly, binding to monocytes could be inhibited with a CCN1-blocking antibody (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Endothelium-bound CCN1 sustains the patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state. (A) Binding of CCN1 (1 μg/mL) was assessed by flow cytometry. For human CCN1, peripheral blood leukocytes were treated with recombinant Fc or human CCN1-Fc for 5 min at room temperature. Human CCN1 binding was detected by flow cytometry using a Dylight 488-conjugated anti-human Fc antibody. For murine CCN1, recombinant CCN1-His (1 μg/mL) was preincubated for 2 h at room temperature with control sheep Ig or blocking polyclonal sheep anti-CCN1 antibodies (50 μg/mL). Then cells were treated with recombinant murine CCN1-His for 5 min at room temperature. Murine CCN1 binding was detected by flow cytometry using a DyLight 650-conjugated anti–His-tag antibody. Data are representative of three experiments. (B) Cell surface-bound CCN1 on live bEnd-5 cells. Cells were incubated with sheep anti-CCN1 antibody or control Ig and then with Cy3-conjugated anti-sheep Ig in the presence of AF488-conjugated anti-PECAM1 to detect the vascular wall surface and the presence of CCN1. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) Representative maximal projections of four preparations are shown. (C) 3D reconstruction of mouse mesenteric veins obtained by confocal intravital microscopy depicting CD115+ patrolling monocytes located next to CCN1 hot spots on the luminal face of mesenteric veins. The view shows the luminal side of the vein. The i.v. injection of AF647-conjugated anti-PECAM1 (CD31, 10 μg) and AF594-conjugated anti-CD115 (1 μg) stained the endothelium blue and monocytes red, respectively. The luminal presence of CCN1-rich areas (green) was assessed after injection of protein A-coupled YFP beads conjugated with a nonblocking antibody to CCN1. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (Movie S1.) (D) Representative tracks of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state (before) and 30 min after injection of control Ig or CCN1-blocking antibodies (50 μg/mL). Fifty monocytes per condition are represented. The arrow indicates the direction of the blood flow. (E) The number of crawling Ly6Clow monocytes and their track duration, speed, and length in D are quantified. n = 4 mice per condition; 25–26 vessels were analyzed in each condition. Data are mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.005; Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

Fig. S1.

CCN1 binding to other populations of leukocytes. Binding of human CCN1 (1 μg/mL) was assessed by flow cytometry. Peripheral blood leukocytes were treated with recombinant Fc or human CCN1-Fc for 5 min at room temperature. Human CCN1 binding was detected by flow cytometry using a Dylight 488-conjugated anti-human Fc antibody. Data are representative of three experiments.

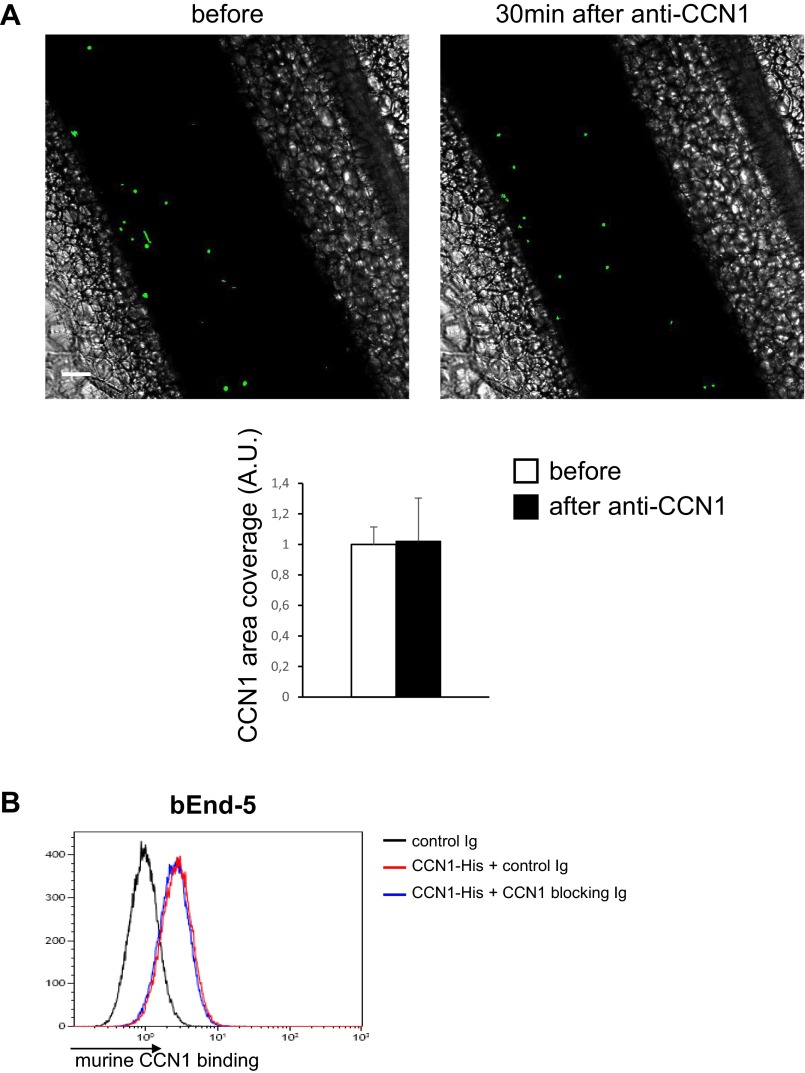

Endothelial cells produce, secrete, and bind to CCN1 through integrin αVβ3 (15, 16). By live microscopy we examined whether CCN1 secreted by endothelial cells coats their surface. A strong CCN1 signal was detected on the surface of live nonfixed bEnd-5 cells labeled with PECAM1 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1) after overnight culture (Fig. 1B). For technical reasons (signal vs. noise), detection of CCN1 coating on the surface of mesenteric veins by intravital confocal microscopy was not achieved. Therefore we adapted a technique previously used to detect endothelium-bound CRAMP (cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide) (26) to investigate whether secreted CCN1 may form dense CCN1-rich areas on the luminal side of mesenteric endothelium. To this purpose, intravital confocal microscopy imaging of mesenteric veins was performed on C57BL/6J mice that had been i.v. injected with fluorescent microbeads conjugated with a CCN1-nonblocking antibody (Fig. S2). In this way we were able to detect CCN1 hot spots but not low levels of CCN1 coating. We observed that CD115+ cells (CD115 is an exclusive marker for blood monocytes) were positioned close to CCN1-rich spots (Fig. 1C and Movie S1). Injection of CCN1-blocking antibodies did not modify the detection of endothelium-bound CCN1 spots (Fig. S3); therefore anti-CCN1 antibody inhibits CCN1 binding only to monocytes and not to endothelial cells.

Fig. S2.

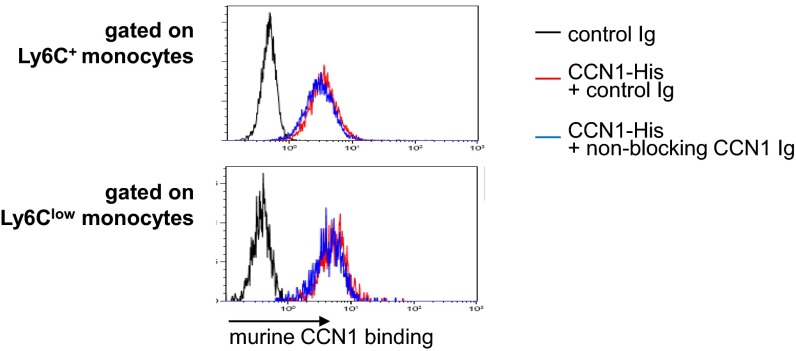

Nonblocking rabbit anti-CCN1 antibody does not affect the binding of CCN1 to monocytes. Binding of murine CCN1 (1 μg/mL) to Ly6C+ monocytes (Upper) and Ly6Clow monocytes (Lower) was assessed by flow cytometry. Recombinant CCN1-His (1 μg/mL) was preincubated for 2 h at room temperature with control rabbit Ig or with nonblocking polyclonal rabbit anti-CCN1 antibodies (50 μg/mL). Then cells were treated with recombinant murine CCN1-His for 5 min at room temperature. Murine CCN1 binding was detected by flow cytometry using a DyLight 650-conjugated anti–His-tag antibody. The y axis represents the percentage of gated cells. Data are representative of three experiments.

Fig. S3.

Blocking sheep anti-CCN1 antibody does not affect the binding of CCN1 to endothelium. (A, Upper) Representative confocal intravital microscopy images of a mesenteric vein in the steady state (before) and 30 min after i.v. injection of sheep anti-CCN1 antibody (50 μg). Luminal CCN1 accumulation was assessed after i.v. injection of protein A-coupled YFP beads conjugated with a nonblocking antibody to CCN1. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (Lower) Quantification in arbitrary units (A.U.). n = 8 vessels per condition. Data are mean ± SEM. (B) Binding of murine CCN1 (1 μg/mL) was assessed by flow cytometry. Recombinant CCN1-His (1 μg/mL) was preincubated for 2 h at room temperature with control rabbit Ig or with nonblocking polyclonal rabbit anti-CCN1 antibodies (50 μg/mL). Then cells were treated with recombinant murine CCN1-His for 5 min at room temperature. Murine CCN1 binding was detected by flow cytometry using a DyLight 650-coupled anti–His-tag antibody. Data are representative of three experiments.

Because monocytes were positioned close to CCN1-rich areas, we investigated whether CCN1 is a molecular partner for the efficient patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes. To explore this possibility, intravital confocal microscopy imaging was set up in vivo to monitor blood monocytes within mesenteric veins in real time. To do so we used Cx3cr1gfp/wt mice, in which both Ly6C+ and Ly6Clow monocytes express eGFP (3, 9, 27). Higher levels of CX3CR1 in patrolling Ly6Clow monocytes result in higher GFP levels, enabling Ly6Clow monocytes to be differentiated from Ly6C+ monocytes by FACS and microscopy (3, 9). After the vasculature was monitored under steady-state conditions, Cx3cr1gfp/wt mice were injected i.v. with either the CCN1-blocking antibody or control Ig. The impact of CCN1 blocking on monocyte patrolling was assessed 30 min later. Injection of control Ig had no impact on the tracks of crawling monocytes (Fig. 1D). In contrast, anti-CCN1 antibody strongly impaired the constitutive crawling-type motility of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state (Fig. 1 D and E). The average instantaneous velocity (speed mean) and the track length of crawling monocytes were decreased compared with controls. However, blocking CCN1 did not alter the number of patrolling monocytes nor the duration of their patrolling activity; therefore CCN1 is not involved in the adhesion of Ly6Clow monocytes to the endothelial wall (Fig. 1E).

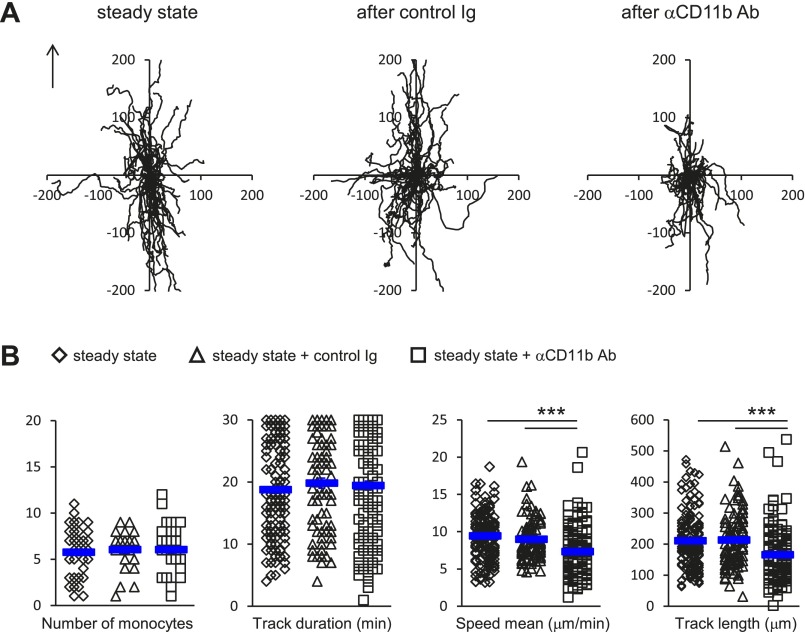

Next, because CD11b is one of the known ligands of CCN1 on monocyte surfaces (20, 25), we evaluated the impact of blocking CD11b on the quality of monocyte patrolling in the steady state by intravital microscopy. The i.v. injection of CD11b-blocking antibodies did not affect the number of patrolling Ly6Clow monocytes (Fig. S4), as previously reported (9). However, the quality of locomotory behavior was altered (Fig. S4), in a manner close to the blocking of CCN1 (Fig. 1 D and E). Overall these data show that endothelium-bound CCN1 is required for the efficient patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state but is not required for their adhesion to the endothelium.

Fig. S4.

CD11b blocking recapitulates the effect of CCN1 blocking on patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state. (A) Representative tracks of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state (before) and after injection of control Ig or blocking anti-CD11b antibodies (50 μg/mL). Fifty monocytes per condition are represented. The arrow indicates the direction of the blood flow. (B) The number of crawling Ly6Clow monocytes and track duration, speed, and length. n = 3 or 4 mice per condition; 27–35 vessels per condition were analyzed. Data are mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.005; Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

CCN1 Mediates Luminal Recruitment of Ly6Clow Monocytes, Which Precede Neutrophils During TLR7/8-Mediated Inflammation.

Ly6Clow monocytes survey blood vessels in the steady state (9). Therefore we reasoned that interactions between CCN1 and Ly6Clow monocytes might be important in the early steps of blood vessel inflammation. To test this idea, we used the TLR7/8 agonist Resiquimod (R848) (28), because Ly6Clow monocytes express high levels of TLR7 and TLR8 (Fig. S5); the homologous human CD14dimCD16+ monocytes also have high levels of TLR7/8, which mediate their response to nucleic acids and viruses (6). We first examined changes in CCN1 levels in inflamed mesenteric vessels by intravital confocal microscopy. Luminal endothelium-bound CCN1 was measured in mesenteric vessels before and 20 min after the induction of inflammation generated by applying R848 directly to the imaged vessels. We observed a threefold luminal increase in CCN1 compared with the steady state (Fig. 2A), strongly suggesting that CCN1 has a role in inflammation.

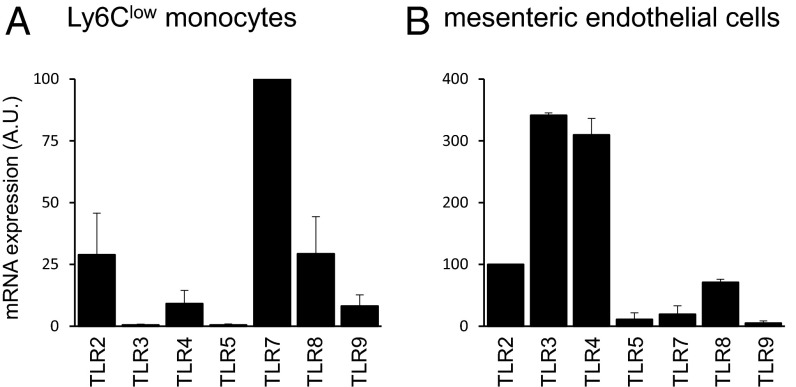

Fig. S5.

TLR expression. Expression of TLRs in Ly6Clow monocytes (n = 4) (A) and mesenteric endothelial cells (n = 3) (B) was determined by quantitative PCR. Data are mean ± SEM.

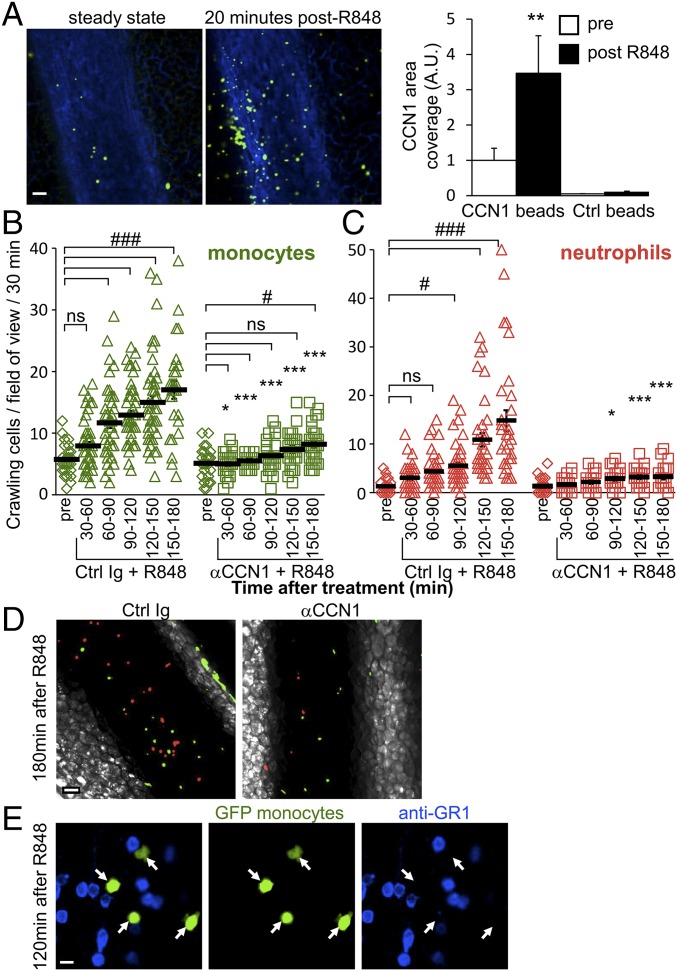

Fig. 2.

CCN1 mediates luminal recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes, which precedes the arrival of neutrophils during TLR7/8-mediated inflammation. (A) Luminal CCN1 accumulation during inflammation. Representative confocal intravital microscopy images of mesenteric vein in the steady state (before) and 20 min after induction of inflammation by treatment with R848 (100 μg). AF647-conjugated anti-PECAM1 (CD31, 10 μg, i.v.) stained the endothelium blue. Luminal CCN1 accumulation was assessed after i.v. injection of protein A-coupled YFP beads conjugated with a nonblocking antibody to CCN1. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) Quantification is provided on the right. “Pre” denotes steady-state conditions before R848 treatment and antibody injection. Protein A-coupled YFP beads conjugated with rabbit Ig were used as controls. Eight vessels from two mice were analyzed. **P < 0.01; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. (B and C) Kinetics of recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes (green) (B) and neutrophils (red) (C) in response to R848 stimulation (100 μg) in Cx3cr1gfp/wt mice transferred with CellTracker Orange-labeled neutrophils. Mice were administered control sheep Ig or CCN1-blocking antibodies (50 μg/mL, i.v.) after steady-state conditions were achieved. Simultaneously, R848 was applied to the monitored vessels to induce inflammation. n = 5–8 mice per condition; 28–50 vessels were analyzed per time point. Data are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005, control (Ctrl) Ig vs. αCCN1 treatment; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.005, antibody and R848 treatment vs. the precondition; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (D) Representative confocal intravital microscopy images of mesenteric vein 180 min after R848 treatment in the presence of control sheep Ig or CCN1-blocking antibodies (50 μg/mL) (from Movie S2 and experiments shown in Fig. 3 B and C). (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (E) Representative confocal intravital microscopy images of mesenteric vein from Movie S4. Mice were administered BV421-conjugated GR1 antibody (1 µg, i.v.) 120 min after R848 treatment. Endogenous neutrophils are labeled in blue, and all monocytes are green. Inflammatory Ly6C+ monocytes would appear in blue and green, and Ly6Clow monocytes only in green. All observed monocytes were GR1−, indicating that they were Ly6Clow monocytes. White arrows indicate the position of monocytes. Fifteen vessels from three mice were analyzed. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

We next evaluated the importance of CCN1 in the kinetics of monocyte and neutrophil recruitment to inflamed mesenteric veins. We i.v. injected CellTracker Orange-labeled murine neutrophils into Cx3cr1gfp/wt mice to visualize monocytes in green and neutrophils in red under steady-state and inflammatory conditions by intravital confocal microscopy (27). After monitoring the locomotory behavior of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state (precondition), mice were i.v. injected with either the CCN1-blocking antibody or control Ig. At the same time, inflammation was generated by directly applying R848 onto the imaged vessels. Time-lapse series of 30 min were recorded, and the number of patrolling monocytes and neutrophils was determined (Fig. 2 B and C). R848 stimulation rapidly recruited crawling monocytes to the endothelium; the wave of neutrophils occurred later (Fig. 2 B and C and Movie S2). Monocytes were actively captured from the flowing blood (Movie S3) or crawled into the field. Interestingly, blocking the binding of CCN1 to monocytes dampened the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes and almost abolished the arrival of neutrophils (Fig. 2D, Fig. S6, and Movie S2). The phenomenon occurred both in large mesenteric veins and in the microvasculature (Fig. S6).

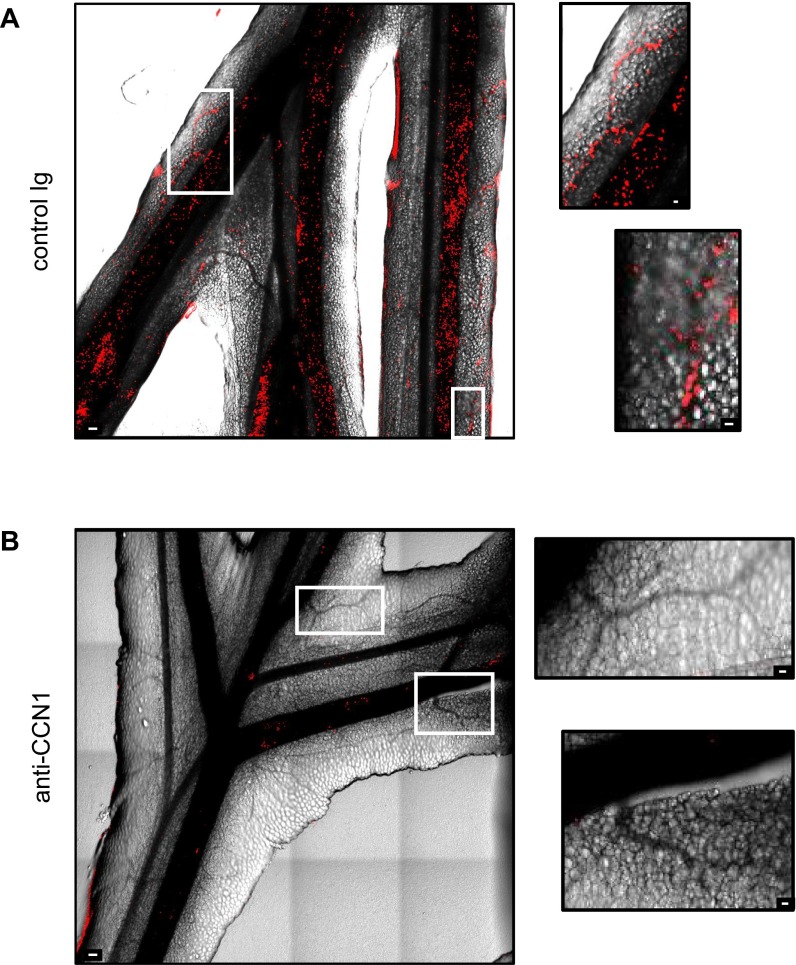

Fig. S6.

CCN1 blocking impairs leukocyte recruitment. Representative maximal projection of stitch images were acquired by confocal intravital microscopy of mesenteric vessels 150 min after the initiation of inflammation with R848 (200 μg) and i.v. injection of control sheep Ig (A) or sheep anti-CCN1 antibody (50 μg) (B). Intravascular neutrophils were detected by i.v. injection of AF647-conjugated anti-Ly6G (0.2 μg) 5 min before starting image acquisition. Vessels are determined by phase contrast. (Scale bars: 100 μm for large images; 25 μm for Insets.) Images are representative of experiments performed on five different mice per condition.

Anti-GR1 antibody recognizes both Ly6C and Ly6G antigens. Therefore, Ly6C+ and Ly6Clow monocytes can be distinguished by their GFP and Ly6C/GR1 expression (4). Although recruited monocytes were GFPhigh, intravital imaging was combined with i.v. injection of labeled anti-GR1 antibody, which stains both neutrophils and Ly6C+ monocytes but not Ly6Clow monocytes. All recruited monocytes that crawled on the endothelium were GR1−, confirming that they were Ly6Clow monocytes (Fig. 2E and Movie S4).

Overall our results demonstrate clearly that CCN1 is required for the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes and that this recruitment precedes the arrival of neutrophils upon TLR7/8-mediated inflammation.

Recruited Neutrophils Extravasate While Accumulated Ly6Clow Monocytes Meticulously Patrol the Luminal Side of the Endothelium upon TLR7/8-Mediated Inflammation.

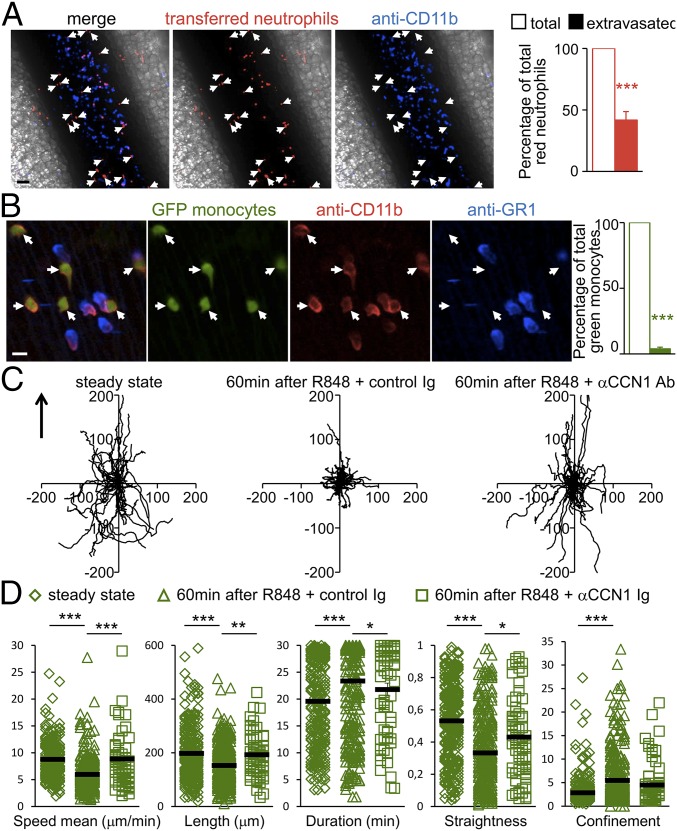

CD11b is present on the surface of all monocytes and neutrophils. Therefore an i.v. injection of labeled anti-CD11b antibodies will stain all cells located in the lumen but not extravasated cells. Two hours after R848 stimulation, i.v. injection of labeled anti-CD11b antibodies (blue) stained around 50% of transferred red neutrophils, indicating the rapid extravasation of neutrophils into the surrounding tissue after their recruitment to the endothelial wall (Fig. 3A). In contrast to the neutrophils, the crawling monocytes were located inside the mesenteric veins, as indicated by their nearly 100% positive labeling with anti-CD11b (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Recruited neutrophils extravasate while accumulated Ly6Clow monocytes meticulously patrol the luminal side of the endothelium upon TLR7/8-mediated inflammation. (A) Recruited neutrophils exit the vessel and invade the surrounding tissue. Shown are representative confocal intravital microscopy images of the mesenteric vein. Mesenteric veins of mice transferred with CellTracker Orange-labeled neutrophils were treated with R848 (100 μg). After 120 min, mice were injected with AF647-conjugated anti-CD11b antibody (1 µg, i.v.). All transferred neutrophils are CD11b+ cells. Endogenous neutrophils are blue. Transferred red neutrophils crawling on the luminal side of the endothelium are in contact with circulating labeled anti-CD11b antibody (red and blue). Extravasated red neutrophils do not have contact with the labeled anti-CD11b antibody and appear only in red (white arrows). (Scale bar: 50 μm.) Quantification is provided on the right. n = 3 mice; 20 vessels were analyzed. ***P < 0.005; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. (B) Ly6Clow monocytes patrol the luminal side of the endothelium. Shown are representative confocal intravital microscopy images of mesenteric vein. AF594-conjugated anti-CD11b and BV421-conjugated anti-GR1 antibodies were administered (1 µg, i.v.) to mice 120 min after R848 treatment. Ly6Clow monocytes are GFP+ (green) and GR1− (not blue). Arrows indicate monocytes. All observed cells were CD11b+ (red), indicating that they are located on the luminal side of the endothelium. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) Quantification is provided on the right. ***P < 0.005; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. n = 3 mice; 16 vessels were analyzed. (C and D) Meticulous patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes after R848 treatment. (C) Representative tracks of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state (before) and 60 min after R848 treatment that were injected with control sheep Ig or antibodies blocking CCN1 (from experiments in B). Fifty monocytes per condition are represented. The arrow indicates the direction of the blood flow. (D) Track speed, length, duration, linearity, and confinement ratio of recruited patrolling Ly6Clow monocytes from experiments in B. Data are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

Analysis of patrolling tracks 60 min after R848 treatment, a time point when the number of Ly6Clow monocytes was already increased (Fig. 2 B and C), revealed a more “meticulous” patrolling behavior of Ly6Clow monocytes than seen in the steady state (Fig. 3 C and D). We observed that R848 increased the duration of attachment of monocytes to the endothelium and that the average instantaneous velocity (speed mean) and the linearity and the length of the track of crawling monocytes were decreased. The more muddled locomotory behavior was also witnessed by the increase of the confinement ratio (track length/track displacement) (Fig. 3 C and D). In contrast, anti-CCN1 antibody prevented the establishment of meticulous patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes, resulting in an intermediate quality of patrolling (Fig. 3 C and D). These data show that Ly6Clow monocytes remain patrolling on the luminal side of the endothelium upon R848 treatment whereas recruited neutrophils exit the vessel.

Luminal Recruitment of Patrolling Ly6Clow Monocytes Relies on Chemokine Receptors.

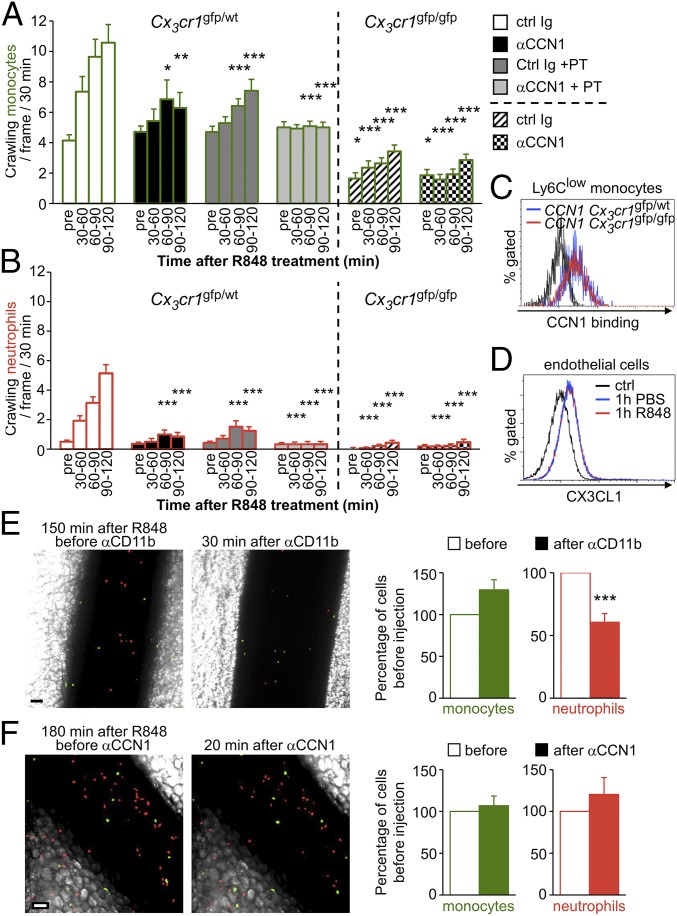

We next wondered whether CCN1 and chemokine receptors use the same pathways for the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes and neutrophils. To this end, we performed the intravital imaging experiments in Cx3cr1gfp/wt mice depicted in Fig. 2 in the presence of pertussis toxin (PT), an inhibitor of chemokine receptor signaling. The i.v. injection of PT or CCN1-blocking antibody alone reduced the recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils (Fig. 4 A and B). Administration of both treatments together completely suppressed the arrival of monocytes and neutrophils in response to R848 (Fig. 4 A and B), showing that CCN1 acts independently of chemokine receptors.

Fig. 4.

Recruitment of patrolling Ly6Clow monocytes relies on chemokine receptors. (A and B) Kinetics of recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes (bars outlined in green) (A) and neutrophils (bars outlined in red) (B) in response to R848 stimulation (100 μg) in Cx3cr1gfp/wt (Left) and Cx3cr1gfp/gfp (Right) mice transferred with CellTracker Orange-labeled neutrophils. After steady-state conditions were recorded, R848 was applied to the monitored vessels to induce inflammation. Simultaneously, mice were i.v. injected with control sheep Ig or antibodies blocking CCN1 in PBS containing PT (50 µg). “Pre” denotes steady state conditions before R848 treatment and antibody injection. n = 3 mice per condition; 14–21 vessels were analyzed per condition. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.005; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (C) FACS analysis of CCN1 binding to Ly6Clow monocytes of Cx3cr1gfp/wt and Cx3cr1gfp/gfp mice. (D) Mesenteric vasculature of C57BL/6J mice was treated with PBS or R848 (100 μg). Then mesenteric endothelial cells were analyzed by FACS for CX3CL1 surface expression. n = 3 mice per condition. (E) Representative confocal intravital microscopy images of mesenteric vein. Mice were injected with anti-CD11b antibody (50 µg, i.v.) 150 min after R848 treatment (100 μg). Thirty minutes later, attached monocytes (green) and neutrophils (red) were quantified. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) Quantification is provided on the right. n = 3 mice; 20 vessels were analyzed. ***P < 0.005; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. (F) Representative confocal intravital microscopy images of mesenteric vein. Mice were injected with anti-CCN1 antibody (50 µg, i.v.) 180 min after R848 treatment (100 μg). Twenty minutes later, attached monocytes (green) and neutrophils (red) were quantified. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) Quantification is provided on the right. n = 2 mice; 14 vessels were analyzed. Data are mean ± SEM.

To establish the importance of Ly6Clow monocyte patrolling in the recruitment of neutrophils, we next performed intravital experiments in Cx3cr1-deficient mice (Cx3cr1gfp/gfp), which have decreased numbers of Ly6Clow monocytes patrolling the endothelium in the steady state (9) as compared with Cx3cr1gfp/wt mice (Fig. 4A), although the binding of Ly6Clow monocytes to CCN1 is normal (Fig. 4C) (9, 29). The recruitment of Cx3cr1-deficient monocytes to the vascular wall was reduced in response to R848 (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the recruitment of neutrophils in Cx3cr1-deficient mice also was compromised (Fig. 4B). Flow cytometry analyses revealed that the expression of fractalkine (CX3CL1), the ligand of chemokine receptor CX3CR1, was not significantly increased on the surface of mesenteric endothelial cells 60 min after topical stimulation of mesenteric vessels with R848 (Fig. 4D). These results confirm that the presence of Ly6Clow monocytes on the vasculature and their ability to patrol efficiently are required to achieve an adequate recruitment of neutrophils in response to R848.

Finally, intravital imaging showed that i.v. injection of antibodies blocking CD11b or CCN1 after R848 stimulation did not affect the attachment of Ly6Clow monocytes (Fig. 4 E and F), as already observed in the steady state (Fig. 1E and Fig. S4B). Therefore, CCN1 and its ligand CD11b are not involved in the attachment of Ly6Clow monocytes even under inflammatory conditions. On the contrary, CD11b blockade after R848 stimulation detached red transferred neutrophils from the endothelial wall (Fig. 4E), indicating the importance of integrin CD11b for the adhesion of neutrophils. We infer that the remaining neutrophils were those that had extravasated and thus were not affected by anti-CD11b injection (Fig. 4A). Because CCN1 does not bind to neutrophils, anti-CCN1 injection had no effect on their attachment (Fig. 4F).

We then examined whether locally necrotic endothelial cells could account for the accumulation of Ly6Clow monocytes. To examine this possibility, we assessed the integrity of mesenteric veins after R848 stimulation. Mice were i.v. injected simultaneously with Sytox, a nucleic acid stain that can be used as an indicator of dead cells, and with anti-PECAM1 to label the vascular wall. 3D reconstruction of vessels revealed no dead endothelial cells even 120 min after stimulation. However, a few dead cells could be observed deep in the tissue surrounding the stimulated vessels (Movie S5). As a positive control for Sytox staining, mesenteric veins were treated with H2O2 to induce cell death. In that case, dead endothelial cells were observed all around the vasculature (Movie S6).

Our data point out that the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes involves a synergic role of chemokine receptors (including CX3CR1) and CCN1 in response to R848 but not in response to local necrosis of endothelium.

Platelet–Ly6Clow Monocyte Interactions Are Required for the Initiation of Inflammation.

Platelets are known to be important for hemostasis, but the number of reports regarding their role in immunity is increasing (30–32). Their ability to recognize pathogens and microbial products contributes to the activation and recruitment of immune cells (33, 34). In fact, efficient interaction between platelets and inflammatory monocytes increases the production of cytokines (35, 36).

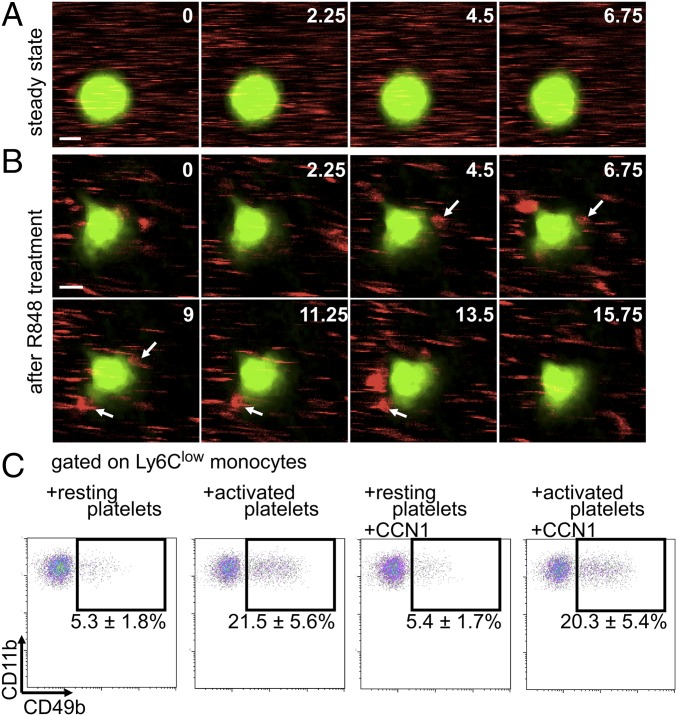

In vivo labeling of mouse platelets with anti-CD49b was described and validated previously (33, 37). We thus performed intravital microscopy of mesenteric veins with anti-CD49b and found numerous interactions between platelets and crawling monocytes as early as 20 min after R848 stimulation, although such interactions were not detected in the steady state (Fig. 5 A and B and Movies S7 and S8). Ly6Clow monocytes seemed to be less polarized and to exhibit smaller lamellipods than during meticulous patrolling in response to R848 stimulation. An average interaction lasted 19.5 ± 1.3 s, and on average each monocyte interacted with 6.9 ± 0.4 platelets every 3 min. These interactions were further confirmed in vitro. Activation of platelets with thrombin strongly increased the percentage of Ly6Clow monocytes interacting with platelets (Fig. 5C), but the presence of CCN1 did not affect these interactions (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Early platelet–Ly6Clow monocyte interactions. (A and B) Intravital microscopy of interactions (arrows in B) of platelets (labeled with anti-CD49b; red) and Ly6Clow monocytes (labeled with GFP, green) in mesenteric veins in the steady state (A) and after R848 stimulation (50 µg) of the vasculature (B). Images in A are from Movie S7. (Scale bar: 5 μm.) Images in B are from Movie S8. Arrows indicate platelets interacting with a monocyte. Numbers in corners indicate time (in seconds). (Scale bar: 5 μm.) Images are representative of 71 monocytes analyzed. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis of platelets interacting with Ly6Clow monocytes. Peripheral blood leukocytes were incubated with thrombin (0.25 U/mL)-activated platelets for 20 min in the presence of recombinant CCN1 (5 µg/mL). Plots are gated on Ly6Clow monocytes. Data are mean ± SEM from four preparations.

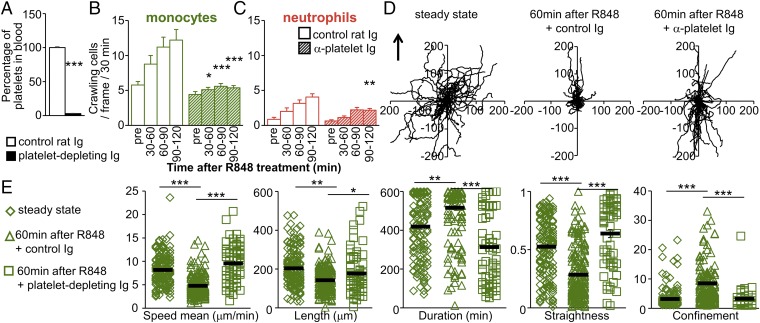

We next studied the role of platelets in early monocyte recruitment in response to R848 by intravital microscopy. Mice were i.v. injected with platelet-depleting antibodies or control Ig. After 60 min (the time needed to eliminate >95% of circulating platelets) (Fig. 6A), we monitored the behavior of Ly6Clow monocytes in response to R848. Depletion of platelets drastically impaired the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes and neutrophils (Fig. 6 B and C and Movie S9). In addition, the locomotory behavior of Ly6Clow monocytes from platelet-depleted mice failed to exhibit the characteristics of meticulous patrolling seen after R848 treatment (Fig. 6 D and E). We did not see protrusions where platelets become trapped in the steady state. In the steady state, patrolling is quick.

Fig. 6.

Platelet–Ly6Clow monocyte interactions are required for the initiation of inflammation and meticulous patrolling. (A) C57BL/6J mice were administered control rat Ig or platelet-depleting antibodies (50 µg, i.v.). Depletion of platelets from blood circulation was evaluated 1 h later by flow cytometry. Data are expressed relative to control rat Ig-treated mice. Three mice were studied per condition. ***P < 0.005; the Mann–Whitney unpaired test was used for statistical analysis. (B and C) Kinetics of recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes (green) (B) and neutrophils (red) (C) in response to R848 stimulation (100 μg) in Cx3cr1gfp/wt mice transferred with CellTracker Orange-labeled neutrophils. Mice were administered control rat Ig or platelet-depleting antibodies (50 µg, i.v.) 1 h before R848 was applied to the monitored vessels. “Pre” denotes steady-state conditions before R848 treatment. Three mice were used, and 19–21 vessels were analyzed per condition. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (D and E) Impaired meticulous patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes after R848 treatment (100 μg) in platelet-depleted mice. (D) Representative tracks of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state (before) and 60 min after R848 treatment from experiments in B in mice injected with control rat Ig or platelet-depleting antibodies. Fifty monocytes per condition are represented. The arrow indicates the direction of the blood flow. (E) Track speed, length, duration, straightness, and confinement ratio of recruited patrolling Ly6Clow monocytes from experiments in B. Data are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005; Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

We conclude that platelets are important for the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes and in the setting of meticulous patrolling upon R848 stimulation.

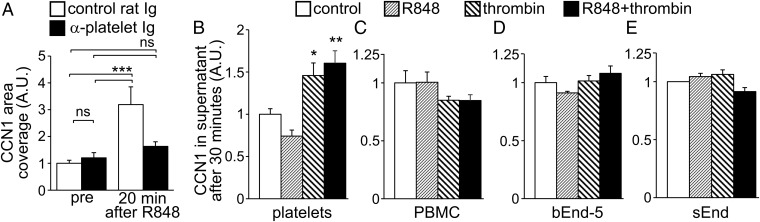

Platelets Contribute to Luminal CCN1 upon TLR7/8-Mediated Inflammation.

Platelet depletion and blocking CCN1 have similar effects on leukocyte recruitment and on the locomotory behavior of Ly6Clow monocytes (Figs. 2, 3, and 6). Moreover platelets are known to produce and release CCN1 in experimentally induced sepsis (22). Therefore we next investigated whether increased luminal CCN1 upon R848 treatment was dependent on platelets. Intravital confocal imaging revealed that depletion of platelets did not affect endothelium-bound CCN1 in mesenteric vessels in the steady state, but it suppressed the increase of endothelium-bound CCN1 in response to TLR7/8 stimulation (Fig. 7A). Treatment of platelets with thrombin alone induced the release of CCN1 within 30 min, whereas R848 had no effect (Fig. 7B). No increase in CCN1 release was observed in similarly stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or in two endothelial cell lines (Fig. 7 C and D).

Fig. 7.

Platelets contribute to luminal CCN1 upon TLR7/8-mediated inflammation. (A) C57BL/6J mice were administered control rat Ig or platelet-depleting antibodies (50 µg, i.v.) 1 h before starting the experiment. Luminal CCN1 accumulation in mesenteric veins in the steady state (before) and 20 min after R848 treatment (100 μg) was assessed after i.v. injection of protein A-coupled YFP beads conjugated with a nonblocking antibody to CCN1. Protein A-coupled YFP beads conjugated with rabbit Ig were used as controls. Data are normalized to the level of CCN1 before R848 treatment of control Ig-treated mice; 19–23 vessels from three mice per group were analyzed. ***P < 0.005; two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (B–E) CCN1 release by platelets (B), PBMCs (C), and bEnd-5 (D) and sEnd cells (E) were assessed by ELISA. Cells were incubated with thrombin (0.25 U/mL) and/or R848 (3 μg/mL) for 30 min. Data are normalized to the level of CCN1 release in the control incubation. Seven independent preparations per condition were used for platelets, and four independent preparations per condition were used for PBMCs and bEnd-5 and sEnd cells. Data are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak multiple comparisons test.

Taken together, our data show that platelets are required for luminal CCN1 upon TLR7/8 stimulation in vivo and, based on in vitro experiments, suggest that they directly release CCN1.

Platelets Potentiate the Production of Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines by Ly6Clow Monocytes.

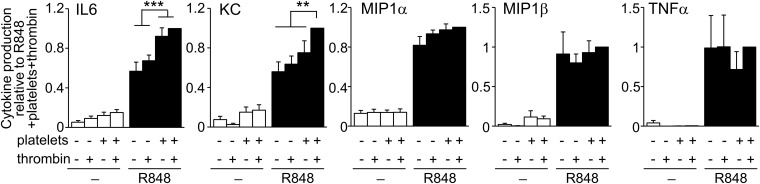

Because Ly6Clow monocytes are recruited before neutrophils (Fig. 2), and this process relies on platelets (Figs. 5 and 6), we tested the capacity of Ly6Clow monocytes to produce cytokines and chemokines relevant to neutrophil recruitment and activation. To this end, FACS-sorted Ly6Clow monocytes were stimulated in vitro with R848 (Fig. 8). The response of Ly6Clow monocytes was characterized by the production of chemokines KC (CXCL1), MIP1α (CCL3), and MIP1β (CCL4) and the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6. The production of KC and MIP1α is of particular interest, because they are well known to contribute to neutrophil recruitment (38). Moreover, the presence of platelets or thrombin-activated platelets further stimulated the production of cytokines by Ly6Clow monocytes, at least regarding the production of IL-6 and KC (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Platelets potentiate the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by Ly6Clow monocytes. Cytokine production by FACS-sorted Ly6Clow monocytes treated for 16 h with R848 (3 μg/mL) in the presence of platelets and thrombin (0.25 U/mL). Data are mean ± SEM normalized to cytokine production in the presence of R848, platelets, and thrombin. n = 4–8 per condition. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005; one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD multiple comparisons test.

Taken together, these data show that interactions between platelets and Ly6Clow monocytes favor the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes, their meticulous patrolling, and their activation upon R848-mediated inflammation.

Discussion

The leukocyte recruitment cascade is often considered to be merely a case of cell transmigration into the injured or infected tissue. Neutrophils are critical in the early steps of the immune response, because they typically are the first leukocytes to be recruited to the inflammatory region, followed by the emigration of Ly6C+/GR1+ monocytes (1, 2). These neutrophils actively participate in the subsequent arrival of Ly6C+/GR1+ monocytes through the release of granule proteins such as cathelicidins, azurocidin, or cathepsin G (26, 38–40), but not that of Ly6Clow monocytes.

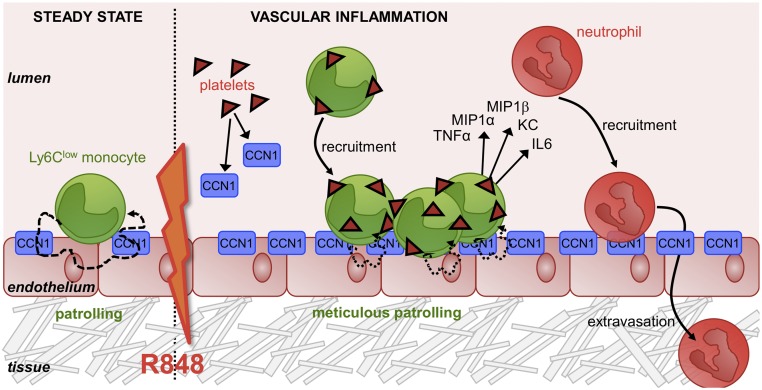

TLR7/8-mediated inflammation of the endothelium by R848 up-regulates ICAM-2, P-selectin, E-selectin, and VCAM-1, leading to peripheral blood leukocyte rolling (41). Here we provide evidence for the role of endothelium-bound CCN1 in leukocyte recruitment. In particular, we demonstrate that activated platelets release CCN1 protein. We show that after R848 stimulation increased endothelium-bound CCN1 mediates the rapid mobilization of Ly6Clow monocytes that remain on the luminal side of the vessel, in accordance with its previously described chemoattractant properties for inflammatory monocytes (15, 16). Direct interactions with platelets and endothelium-bound CCN1 commit accumulated Ly6Clow monocytes to a meticulous patrolling of the vascular wall and the local production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, thus controlling the initial capture of neutrophils from the circulation. The surrounding inflamed tissue obviously produces strong chemotactic gradients supporting the later rapid extravasation of neutrophils (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Model of the CCN1-mediated mechanisms of vascular inflammation. Schematic representation of Ly6Clow monocytes’ behavior with the endothelium in the steady state and after TLR7/8-mediated vascular inflammation. CCN1 sustains the patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state. Under inflammatory conditions, CCN1 is released by platelets. Luminal accumulation of CCN1 stimulates the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes. While interacting with platelets, mobilized Ly6Clow monocytes meticulously patrol the luminal face of the vasculature and orchestrate the recruitment of neutrophils via the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

Ly6Clow monocytes constitutively patrol the endothelium and rarely extravasate in the steady state (9), whereas they rapidly invade the peritoneal cavity in response to Listeria monocytogenes infection (9). In contrast, they are mobilized tardily to the injured myocardium a few days after inflammatory Ly6C+ monocytes (42). Here we show that Ly6Clow monocytes do not extravasate in response to R848, as also observed in kidney capillaries (10). Instead the Ly6Clow monocytes remain in the lumen and meticulously patrol the endothelial wall, a locomotory behavior characterized by enhanced adhesion time, decreased speed, and decreased track length in mesenteric veins. Conversely, in the kidney microvasculature, Carlin et al. (10) found that the track length of Ly6Clow monocytes increased upon TLR7 stimulation. They also showed that Ly6Clow monocytes are responsible for the luminal recruitment of neutrophils to kill endothelial cells of the kidney microvasculature and that the remaining cell debris is scavenged by monocytes (10). In our study of the mesenteric vasculature, we did not observe endothelial cell death. However, some dead nonendothelial cells could be observed deep in the surrounding tissue 2 h after the initiation of inflammation. We also report that neutrophils extravasate rapidly after Ly6Clow monocyte-dependent recruitment. The wave of neutrophils began around 90 min after R848 stimulation, and many had extravasated by 120 min. Neutrophils thus remain crawling on the luminal side of the vessel for a very short period. In contrast, Ly6Clow monocytes were significantly increased and remained on the luminal side throughout the course of the experiment. The discrepancy between the studies may result from the functional and physical differences between kidney capillaries and mesenteric veins. Notably patrolling Ly6Clow monocytes are 10 times more abundant in kidney microvasculature than in the mesentery (10).

Inflammation increases the number of activated platelets in the circulation (31, 32, 43, 44). We show here that activation of platelets is required for the recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes and to stimulate their cytokine production. However, we did not observe platelet accumulation on the endothelial surface or thrombus formation. We presume that platelet-activating signals do not reach a threshold necessary for thrombus formation. Confocal intravital microscopy also revealed transient but repeated interactions with Ly6Clow monocytes after R848 treatment. Trapping in monocyte protrusions may participate in the establishment of meticulous patrolling. However, we did not investigate the molecules responsible for these interactions. Although TLR7 is expressed by human and murine platelets and mediates platelet aggregation to leukocytes (34), R848 treatment alone did not stimulate CCN1 release. In contrast, thrombin elicits changes in the shape of platelets, the release of the platelet activators ADP, serotonin, and thromboxane A2 (43–45), and also the release of CCN1, as shown here and previously (22). Activated platelets are able to bind to leukocytes, preferentially to monocytes through the expression of P-selectin (32, 35), which is mobilized to the surface of TLR7 agonist-stimulated and thrombin-activated platelets (34, 43, 44). In this way, they participate in the activation and recruitment of immune cells (30, 31, 33, 46), acting as chaperones. Activated platelets were reported to bind more quickly and more intensely to monocytes than to neutrophils (31). However, we observed no interaction between Ly6Clow monocytes and platelets in the steady state, perhaps because the setup of our microscope allowed the detection only of interactions lasting longer than 2 s. Therefore, we cannot entirely rule out brief interactions in the steady state, such as the “touch-and-go” events observed with Kupffer cells in liver sinusoids (33). We also report that Ly6Clow monocytes are responsive to R848 in terms of cytokine and chemokine production, as is consistent with findings on their human homologs, CD14dimCD16+ monocytes, which respond to nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7/8 (6). In addition, interactions with platelets further improve the production of KC and IL-6, as would be expected from platelets’ role in stimulating cytokine production by inflammatory monocytes (35, 36). Therefore, platelets have at least three functions in our model: (i) recruitment of Ly6Clow monocytes; (ii) commitment to meticulous patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes; and (iii) promotion of cytokine production by Ly6Clow monocytes via direct interaction and/or release of CCN1.

Matricellular protein CYR61/CCN1 has been studied extensively in cancer development and wound healing (15, 16, 47, 48). In addition to confirming the chemoattractant properties of CCN1 on monocytes/macrophages (18, 20, 21), we also show that CCN1 sustains the patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes and is important for the initiation of inflammation. We used i.v. injection of CCN1-blocking antibodies in WT mice to circumvent the lethality of Ccn1-null mice, which results from the impairment of vascular integrity and cardiovascular development dysfunction (24). Patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes is dependent on CD18, CD11a, ICAM1, ICAM2, and CX3CR1 (9, 10). Here we report that endothelium-bound CCN1 constitutes a molecular support for monocyte patrolling in the steady state but is not required for monocyte adhesion to the endothelium. CD11b is an integrin able to engage multiple ligands, counter receptors, or products of coagulation and complement (49), one of which is CCN1 on monocytes and macrophages (15, 16, 20, 21, 25). A role of CD11b in the patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes was ruled out initially (9), based solely on the observation that anti-CD11b injection does affect the adhesion of crawling monocytes to the endothelium but without examining the locomotory behavior (9). Here we show that blocking CD11b recapitulated in part the phenotype of CCN1 blocking, affecting the locomotion of monocytes without affecting their adhesion in the steady state.

In this study, we focus on the early steps of inflammation. We pinpoint platelets as a source for endothelium-bound CCN1 after R848 stimulation, because activated platelets released CCN1 in vitro and depletion of platelets suppressed inflammation-induced endothelium-bound CCN1 increase in vivo. Because platelets were observed only in contact with Ly6Clow patrolling monocytes and not attached to the endothelium, we speculate that activated platelets release CCN1 in the circulation which then binds to the inflamed endothelium. Neither murine PBMCs nor endothelial cells released CCN1 on a short-term basis, although endothelial cell-derived CCN1 coats the surface of these cells in the steady state and 18-h treatment with TNF-α and bafilomycin A1 stimulated CCN1 release by human PBMCs (18). These results are in accordance with the chemoattractant properties of CCN1 for monocytes/macrophages in the early phase of inflammation, whereas PBMC-derived CCN1 locally immobilize recruited leukocytes in the invaded tissue after extravasation at later time points (18, 19, 50–53).

Live imaging of endogenous neutrophils may be tricky at long-time points as antibodies used to detect them have depleting and/or blocking properties. In order to avoid functional interference with neutrophil behavior, we preferred to inject negatively selected neutrophils labeled with Cell-Tracker Orange. We observed no difference between the rolling of transferred and endogenous neutrophils (Movie S10). Another issue with live imaging is the detection of chemokines. In our case, live detection of CCN1 would certainly require an antibody with a higher affinity because the background signal was too high in mesenteric veins. To circumvent the detection problem, we adapted a technique previously used to detect endothelium-bound CRAMP (26) that allowed the monitoring of the luminal accumulation of CCN1 in response to R848, which is a ligand for TLR7/8 (28). Such a result reinforces the idea that CCN1 has a role in antiviral responses and TLR7 recognition of viral single-strand RNA (54). Indeed, hepatitis C virus, coxsackievirus B3, and herpes simplex virus type1 were shown to induce CCN1 expression in vitro and in vivo (15). CCN1 accumulation mediates the rapid mobilization of Ly6Clow monocytes to the endothelium in response to TLR7/8-mediated local inflammation of the vasculature. Mobilization of Ly6Clow monocytes and adequate patrolling motion are mandatory for the arrival of neutrophils, as evidenced by experiments with anti-CCN1 and antiplatelet antibodies. The recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils also was reduced in Cx3cr1-deficient mice that exhibit lower numbers of patrolling Ly6Clow monocytes, underlining the early importance of patrolling in leukocyte recruitment in response to R848. However, Cx3cr1-deficient mice have no defects in neutrophil recruitment when challenged with the complex TLR7-independent pathogens Clostridium difficile and Candida albicans and or in recruitment at later time points (55, 56). This finding argues in favor of a local and timely impact of CCN1 and Ly6Clow monocytes or a role restricted to TLR7/8-mediated inflammation.

Our results have important implications for pathologies involving inflammation. Circulating activated platelets promote inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis patients (57). Interactions with monocytes and the endothelium of the vessel wall in ApoE−/− mice enable the deposition of chemokines on the cell surface and the recruitment of monocytes and thus accelerate the development of atherosclerotic plaques (58) that exhibit intense CCN1 expression (25). Platelet activation markers and soluble adhesion molecules are also observed in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (59). Increased recruitment of human CD16+ monocytes into synovial tissues and glomeruli is also seen in rheumatoid arthritis and lupus patients, respectively (6, 60–63), and murine Ly6Clow/Gr1low monocytes are expanded in the Yaa model of SLE (14). Interestingly, increased soluble CCN1 levels are observed in synovial fluid from rheumatoid arthritis patients (15) and in the serum of SLE patients (64). Hence, the chemoattractant properties of CCN1 for human and murine monocytes and macrophages (15, 16, 18, 19) strongly implicates CCN1 in the numerous pathologies in which TLR7 activity plays an important role.

Collectively, our data provide evidence for refining the model of the leukocyte recruitment cascade and the TLR7/8-mediated response. The commitment of Ly6Clow monocytes to surveying the endothelial wall reinforces the proposition that they should be considered luminal blood macrophages (11). The accumulation and meticulous patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes on the luminal side of the endothelium and their interaction with platelets also demonstrates that leukocytes can play an active role in inflammation without extravagating. The therapeutic targeting of Ly6Clow monocytes and CCN1 to control leukocyte recruitment and the course of inflammation in human pathologies remains an interesting possibility for future investigation.

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Animals.

Cx3crgfp/gfp mice were initially obtained from Charles River Laboratories. C57BL/6J mice were from Charles River Laboratories or from the animal facility of the University of Geneva. All animals were kept on a C57BL/6J background in the specific pathogen-free animal facility of the University of Geneva.

Statistics.

Statistical calculations were carried out in Prism 6 (GraphPad). Mann–Whitney unpaired test, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons tests, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD), Holm–Sidak multiple comparisons tests, and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s or Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests were used as appropriate. All statistical tests are two-sided. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

Study Approval.

Animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Ethical Committee of Animal Care in Geneva, Switzerland and the Cantonal Veterinary Office.

SI Materials and Methods

Antibodies.

The following antibodies were purchased from BioLegend: AF488-, PE-, and AC7- conjugated anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7); BV421- and AF647-conjugated GR1 (clone RB6-8C5); AF488- and AF647-conjugated anti-PECAM1 (clone 390); BV711- and PE-conjugated anti-CD115 (clone AFS98); PE-conjugated anti-CD49b (clone HMa2); AC7-conjugated anti-CD19 (clone 6D5); AC7-conjugated anti-TCRb (clone H57-597); BV421-, AF594-, and AF647-conjugated anti-CD11b (clone M1/70); AF488- and BV421-conjugated anti-Ly6C (clone HK1.4); BV421- and PC5.5-conjugated anti-Ly6G (clone 1A8); PE-conjugated anti-CD62P (RMP-1); and PE-conjugated anti-CD49b (clone HMα2). PE- and APC-conjugated anti-CD115 (clone AFS98), eFluor450-conjugated anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7), and anti-CD11b (clone M1/70) were purchased from eBioscience. DyLight 488- and DyLight 650-conjugated anti-human IgG and DyLight 488- and DyLight 650-conjugated anti-6×His–tagged antibody (clone AD1.1.10) were purchased from Abcam. Cy3-conjugated anti-sheep Ig and HRP-conjugated anti-sheep Ig were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Anti-CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2) was purchased from BD Pharmingen. Nonblocking rabbit polyclonal anti-human/mouse CCN1/CYR61 was purchased from Millipore. Blocking sheep polyclonal anti-mouse CCN1/CYR61 was purchased from R&D systems.

Intravital Confocal Microscopy.

Experiments were conducted on C57BL/6J, Cx3cr1gfp/wt, and Cx3cr1gfp/gfp mice as previously described (27). An anesthetized mouse (ketamine 60 mg/kg, xylazine 4.5 mg/kg, acepromazone 1.75 mg/kg) was placed on a heating pad to maintain body temperature. Abdominal skin and peritoneum were incised to expose the intestine. To expose the mesenteric vessels, sterilized cotton buds were used to unroll the intestine onto a coverslip (35 mm in diameter) placed inside a cell-culture dish that had a 300-mm diameter hole. The intestine was immobilized with PBS-moistened tissue to decrease peristaltic movements. The vasculature was never allowed to dry; prewarmed PBS was used to humidify tissue and vasculature regularly. The preparation was put inside a temperature-controlled chamber (37 °C) and was placed a custom-made tray stage of an inverted Nikon A1r microscope. Boosts of anesthetics were delivered i.m. every 30 min to maintain adequate anesthesia. Mouse eyes were protected with an ocular gel. The mouse preparation involves surgery that slightly stresses the endothelium, and thus rolling leukocytes may be observed during the first 15 min following mouse preparation. Therefore the mouse and the mesenteric vessels were allowed to recover from the preparation for 30 min for the vasculature to return to a resting state. The first images were acquired after this procedure. This first movie, called “pre condition,” shows the patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes in the steady state. Each movie was acquired with a 20× objective (20× CFI Plan Apochromat, VC 0.75, DT: 1 mm) and lasts 30 min with a time frame of 20 s. Laser power was 0.15–0.25 mW. Numerical zoom was used in some cases (platelet–monocyte interaction, 3D stacks). Images of 512 × 512 pixels (i.e., 635 μm) were acquired at 1.1 s per channel with the Galvano scanner of the inverted Nikon A1r confocal microscope. For recruitment kinetics and monocyte–platelet interactions, acquisition was at a single z; z-depth was 12–16 µm. Phase contrast allows the identification of endothelial walls, and imaging was performed on mesenteric veins. Files were acquired with Nikon NIS Elements software and were posttreated with ImageJ.

Antibody blocking experiments under steady-state conditions.

Anti-CD11b (clone M1/70) (50 μg), 50 μg of anti-CYR61/CCN1 (sheep polyclonal), or 50 μg of the appropriate control Ig (in 100 μL of PBS preheated to 37 °C) was i.v. injected after the acquisition of pre-condition images. The impact of CD11b blocking on the patrolling of Ly6Clow monocytes was investigated for 30 min immediately after the injection of antibodies. The impact of CCN1 blocking was investigated for 30 min beginning 30 min after injection.

Kinetics of monocyte and neutrophil recruitment upon R848 stimulation.

Antibodies specifically labeling murine neutrophils have blocking and depleting properties. Therefore the injection of even low levels of anti-Ly6G or anti-GR1 blocking/depleting antibodies to detect endogenous neutrophils in kinetic experiments lasting several hours may interfere with neutrophil behavior. To avoid functional interference, we injected negatively selected neutrophils (magnetic bead separation, see below) labeled with CellTracker Orange. We observed no difference between the rolling of transferred and endogenous neutrophils (Movie S10). Similarly, Swamydas et al. (65) showed that neutrophils purified from bone marrow can be used in transfer experiments for trafficking studies. Hasenberg et al. (66) showed that negatively purified neutrophils from murine bone marrow exhibited normal functional activity in vitro and in vivo when transferred to mice. In this way, bone marrow-derived neutrophils transferred into Trypanosoma-infected recipient mice migrated efficiently and produced cytokines (67).

Neutrophils were obtained from bone marrow of C57BL/6J mice using the EasySep Mouse Neutrophil Enrichment kit (Stem Cell Technologies). After purification, cells were stained with CellTracker Orange CMRA (Invitrogen), and 10 million cells (in 100 μL of PBS) were i.v. injected into anesthetized Cx3cr1gfp/wt and Cx3cr1gfp/gfp mice just before mouse preparation for intravital imaging. After the acquisition of the pre-condition movie, 100 μg of R848 diluted in 20 μL of PBS was applied directly to the imaged mesenteric vessels for TLR7/8 stimulation. Imaging of inflamed vessels started immediately upon R848 application. Each movie lasts 30 min with a time frame of 20 s, beginning 30 min or up to 3 h after the induction of inflammation. The addition of TLR agonists alters the vessel width and therefore the focus. Consequently, it is very difficult to image properly the first 10–15 min after stimulation, before the vessels stabilize. Therefore, the first movie to be analyzed starts 30 min after TLR stimulation with a frame rate of 20 sand a scanning speed of 2.2 s. Monocytes were tracked using the Spot Tracking Wizard of Imaris software (Bitplane). Movie files were posttreated in ImageJ. First, a median filter was applied to the green and red channels; then files were converted to binary files and saved as .avi.

Large image for neutrophil recruitment.

Seven-week-old C57bl6J mice were prepared for intravital confocal imaging as above. Inflammation was induced by applying R848 (200 μg) directly to the vessels. Simultaneously sheep anti-CCN1 antibody or control sheep Ig (50 μg) was i.v. injected. In vivo labeling of neutrophils was performed 150 min after the initiation of inflammation by i.v. injection of AF647-conjugated anti-Ly6G (0.2 μg) and 5 min before starting image acquisition with a Plan Apo 10× DIC L objective. Stacks of 10 μm were done. NIS software allowed acquisition and stitching of images to obtain the large images shown.

Platelet detection, depletion, and interaction with Ly6Clow monocytes.

In vivo labeling of mouse platelets with anti-CD49b was adapted from Jenne et al. (37). Cx3cr1gfp/wt mice were anesthetized and i.v. injected with 1 μg PE-conjugated anti-CD49b (clone HMα2) in 100 μL of PBS before mouse preparation as described above for intravital imaging. Movies of the steady-state condition were recorded for 3 min. Mesenteric vessels were stimulated with R848 as described above, and interactions between platelets and Ly6Clow monocytes were recorded for 3 min with a time frame of 2.25 s and a scanning speed of 2.2 s.

Platelet depletion was achieved through i.v. injection of platelet-depleting antibody (Emfret Analytics). After 1 h, mesenteric veins were stimulated with R848. As control, rat Ig (R&D Systems) was injected.

Ly6C and CD11b phenotyping, CD11b and CCN1 blocking, and dead cell detection.

In some experiments, 2 h after induction of inflammation, 1 μg AF647- or AF594-conjugated anti-CD11b (clone M1/70), or BV421-conjugated or AF647-conjugated anti-GR1 (clone RB6-8C5), or 10 μg AF647-conjugated anti-PECAM1 (clone 390) in 100 μL of PBS (preheated to 37 °C) was i.v. injected. Anti-GR1 labels endogenous and transferred neutrophils and inflammatory Ly6C+ monocytes but not Ly6Clow monocytes. Anti-CD11b and anti-GR1 labeling allows the identification of extravasated monocytes and transferred neutrophils.

To determine the importance of CD11b and CCN1 in the adhesion of neutrophils and Ly6Clow monocytes to the endothelium, 50 μg of CD11b antibody (clone M1/70) or 50 μg of CCN1-blocking antibody (sheep polyclonal) was i.v. injected 2 h after the induction of inflammation.

For cell death detection, C57BL/6J mice were prepared as described above for intravital imaging and were stimulated with 100 μg of R848. Two hours later, mice were i.v. injected with 10 μL Sytox Blue (stock; 5 mM) or 10 μg AF647 or AF488-conjugated anti-PECAM1 (clone 390) in 100 μL of PBS (preheated to 37 °C). Images of mesenteric vessels were acquired immediately with a 20× objective. For 3D stacks, z stacks of 1-μm thickness were acquired and reconstructed with Imaris (Bitplane).

Luminal CCN1 binding.

For luminal detection of CCN1 presented on the endothelium, the method was adapted from Wantha et al. (26). Fifty microliters of Protein A Fluoresbrite Yellow Green Microspheres (1-μm diameter) (Polysciences) was coupled to 50 μg of nonblocking rabbit polyclonal antibody to CCN1 (Millipore). Beads were washed three times in PBS and then reacted with antibody for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes, beads were ready for injection. C57BL/6J mice were prepared as described above for intravital imaging and were i.v. injected with 100 μL of prewarmed PBS containing 10 μg of AF647-conjugated anti-PECAM1 (clone 390). If needed, 1 μg of AF594-conjugated anti-CD115 (clone AFS98) was coinjected to determine the position of monocytes relative to CCN1-dense spots. Inflammation was induced by local application of R848 (100 μg).

Surface-Bound CCN1 Detection on Live Cells.

bEnd-5 endothelial cells were plated overnight in Ibidi microslides in phenol red-free RPMI + 10% FCS. Cells were incubated directly with sheep anti-CCN1 antibody (R&D Systems) or control sheep Ig (R&D Systems) for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing in RPMI, cells were incubated for 1 h with Cy3-conjugated anti-sheep Ig (Jackson ImmunoResearch) in the presence of AF488-conjugated anti-PECAM1 (BioLegend) in RPMI + 2% FCS. After washing in RPMI, cells were cultured in RPMI + 2% FCS. Images were acquired with a Nikon A1R confocal microscope to detect the presence of surface CCN1 and were analyzed with ImageJ.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

Cells were sorted on a MoFlow Astrios (Beckman-Coulter), an Aria Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences), or a S3 Cell Sorter (Bio-Rad) and then were resuspended in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) for total RNA preparation and were purified using the PureLink RNA Micro Kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized with random hexamers and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed with the iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR Detection System and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Expression of TLRs and of CYR61/CCN1 was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using specific PrimePCR primers (Bio-Rad) for the respective candidate molecules. The primer sequences for cyclophilin were forward ATGGCAAATGCTGGACCAA and reverse GCCATCCAGCCATTCAGTCT.

Isolation of Mesenteric Endothelial Cells.

Mesenteric endothelial cells were obtained by digestion in HBSS containing Liberase (Roche) and DNase I. Cell suspensions were labeled with anti-PECAM1 and anti-CD45 and were sorted on an Aria II FACS sorter (BD Biosciences).

CYR61/CCN1 Binding by Flow Cytometry.

Recombinant human CCN1-Fc and Fc molecules were purchased from R&D Systems. Recombinant murine CCN1-His was purchased from Cusabio.

Binding was adapted from the method previously used for CCN1 binding to thymic cells (17). Murine blood was collect into EDTA microcuvettes (Sarstedt). Red cells were lysed (NH4Cl, NaHCO3, EDTA). Then leukocytes were washed and incubated in phenol red-free DMEM/F12 (Gibco) at room temperature for 10 min in the presence of Fc block (clone 2.4G2; BD Pharmingen). Then cells were labeled with anti-CD115, CD11b, TCR, CD19, Ly6C, and Ly6G antibodies for 10 min followed by treatment with recombinant human Fc (1 μg/mL), human CCN1-Fc (1 μg/mL), or murine CCN1-His (1 μg/mL) for 5 min at room temperature. After washing in phenol red-free DMEM/F12, cells were incubated for 5 min at room temperature with DyLight 488- or DyLight 650-conjugated anti-human Fc antibody (Abcam) to detect human CYR61-Fc binding or with AF488-conjugated anti-6ΧHis–tagged antibody (Abcam). After washing in phenol red-free DMEM/F12, binding was assessed by flow cytometry (Gallios; Beckman Coulter).

Binding to bEnd-5 cells was assayed in a similar manner. After trypsinization, cells were washed and incubated in phenol red-free DMEM/F12 at room temperature for 10 min in the presence of Fc block and then were incubated with murine CCN1-His (1 μg/mL) for 5 min at room temperature. After washing in phenol red-free DMEM/F12, cells were incubated for 5 min at room temperature with AF488-conjugated anti-6×His–tagged antibody in the presence of AF647-conjugated anti-PECAM1.

For experiments involving the blocking of CCN1 binding, recombinant CCN1-His was preincubated for 2 h at room temperature with blocking sheep anti-mouse CCN1 or nonblocking rabbit anti-CCN1, sheep Ig, or rabbit Ig (50 μg/mL) before the treatment of leukocytes and bEnd-5 cells.

Platelet Isolation.

Blood was collected in citrate-phosphate-dextrose (Sigma Aldrich) containing PGE1 (1 μM) and was centrifuged at 200 × g for 20 min at room temperature (no brake). Platelet-rich plasma was transferred to a new tube with an equal volume of HEP buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 3.8 mM Hepes, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). After centrifugation (150 × g for 15 min at room temperature), the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and pelleted by centrifugation (800 × g for 15 min at room temperature). The platelet pellet was resuspended in phenol red-free Opti-MEM and dispatched for monocyte–platelet interactions and cytokine production.

Measurement of CCN1 in Supernatants.

PBMCs were resuspended in RPMI without serum and platelets in Tyrode’s buffer (5 mM glucose) and were stimulated with thrombin (0.25 U/mL) and/or R848 (3 μg/mL) for 30 min at 37 °C. bEnd-5 endothelial cells were cultured overnight in RPMI + 10% FCS, washed with phenol red-free RPMI, and incubated for 2 h in RPMI + 2% FCS. Stimuli were added directly to the wells. After stimulation, samples were centrifuged (2,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature) and kept at −20 °C until assay. CCN1 levels were determined by direct ELISA using sheep anti-mouse CCN1 antibody (R&D Systems), HRP-conjugated anti-sheep Ig antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and the 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) liquid substrate system (KPL).

Platelet–Monocyte Interactions.

Leukocytes were obtained from C57bl6J mice after red cell lysis (NH4Cl, NaHCO3, EDTA) and were resuspended in Opti-MEM. After washing, Fc receptors were blocked with anti-CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2), and leukocytes were incubated for 20 min at room temperature with platelets in the presence of thrombin (0.25 U/mL), CCN1 (5 μg/mL), and labeled antibodies (anti-CD115, anti-CD49b, anti-CD11b, and anti-Ly6C). To stabilize platelet–leukocyte interactions, paraformaldehyde was added to reach a final concentration of 2% for 5 min. Cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer. Interactions were assessed by flow cytometry (Gallios; Beckman Coulter).

Production of Cytokines and Chemokines.

Leukocytes were obtained from C57bl6J mice after red cell lysis (NH4Cl, NaHCO3, EDTA). SSClow, Ly6G−, TCRβ−, CD19−, CD11b+, CD115+, and Ly6Clow monocytes were sorted on a MoFlow Astrios (Beckman Coulter) in 96-well plates. Ly6Clow monocytes (1 × 104) were stimulated overnight in Opti-MEM and 5% FCS with R848 (3 μg/mL) and/or thrombin (0.25 U/mL) in the presence or absence of platelets. Platelets were prepared as described above. Platelets obtained from one mouse were equally dispatched in each well. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and were stored at −80 °C until analysis. IL-6, KC, MIP1α, MIP1β, and TNF-α were assessed using the Bio-Rad Bio-Plex Multiplex murine cytokine kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Results of each series were normalized to the production of cytokines from monocytes stimulated simultaneously with R848, platelets, and thrombin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bioimaging and Flow Cytometry core facilities of the University of Geneva for technical assistance; M. A. Meier for fruitful discussions; Dr. B. Karoubi for monocyte tracking; and Dr. N. Magon and Dr. T. Venables for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the European Molecular Biology Organization (Y.E.), Foundation Machaon (Y.E.), and the Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 310030_153456 (to B.A.I.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. P.K. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1607710113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ryan GB, Majno G. Acute inflammation. A review. Am J Pathol. 1977;86(1):183–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soehnlein O, Lindbom L, Weber C. Mechanisms underlying neutrophil-mediated monocyte recruitment. Blood. 2009;114(21):4613–4623. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-221630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19(1):71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunderkötter C, et al. Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2004;172(7):4410–4417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geissmann F, et al. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327(5966):656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cros J, et al. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33(3):375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tacke F, et al. Monocyte subsets differentially employ CCR2, CCR5, and CX3CR1 to accumulate within atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):185–194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf D, Zirlik A, Ley K. Beyond vascular inflammation--recent advances in understanding atherosclerosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(20):3853–3869. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1971-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auffray C, et al. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317(5838):666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlin LM, et al. Nr4a1-dependent Ly6C(low) monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell. 2013;153(2):362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: Developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(6):392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamers AA, et al. Bone marrow-specific deficiency of nuclear receptor Nur77 enhances atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2012;110(3):428–438. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanna RN, et al. NR4A1 (Nur77) deletion polarizes macrophages toward an inflammatory phenotype and increases atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2012;110(3):416–427. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amano H, et al. Selective expansion of a monocyte subset expressing the CD11c dendritic cell marker in the Yaa model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2790–2798. doi: 10.1002/art.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emre Y, Imhof BA. Matricellular protein CCN1/CYR61: A new player in inflammation and leukocyte trafficking. Semin Immunopathol. 2014;36(2):253–259. doi: 10.1007/s00281-014-0420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau LF. CCN1/CYR61: The very model of a modern matricellular protein. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(19):3149–3163. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0778-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emre Y, et al. Thymic epithelial cell expansion through matricellular protein CYR61 boosts progenitor homing and T-cell output. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2842. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löbel M, et al. CCN1: A novel inflammation-regulated biphasic immune cell migration modulator. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(18):3101–3113. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0981-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shigeoka M, et al. Cyr61 promotes CD204 expression and the migration of macrophages via MEK/ERK pathway in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2015;4(3):437–446. doi: 10.1002/cam4.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schober JM, et al. Identification of integrin alpha(M)beta(2) as an adhesion receptor on peripheral blood monocytes for Cyr61 (CCN1) and connective tissue growth factor (CCN2): Immediate-early gene products expressed in atherosclerotic lesions. Blood. 2002;99(12):4457–4465. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai T, Chen CC, Lau LF. Matricellular protein CCN1 activates a proinflammatory genetic program in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;184(6):3223–3232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hviid CV, et al. The matricellular “cysteine-rich protein 61” is released from activated platelets and increased in the circulation during experimentally induced sepsis. Shock. 2014;41(3):233–240. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hviid CV, et al. The matri-cellular proteins ‘cysteine-rich, angiogenic-inducer, 61’ and ‘connective tissue growth factor’ are regulated in experimentally-induced sepsis with multiple organ dysfunction. Innate Immun. 2012;18(5):717–726. doi: 10.1177/1753425912436764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mo FE, et al. CYR61 (CCN1) is essential for placental development and vascular integrity. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(24):8709–8720. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8709-8720.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schober JM, Lau LF, Ugarova TP, Lam SC. Identification of a novel integrin alphaMbeta2 binding site in CCN1 (CYR61), a matricellular protein expressed in healing wounds and atherosclerotic lesions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(28):25808–25815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301534200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]