Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a prevalent psychiatric disorder. Several studies have attempted to characterize molecular alterations associated with PTSD, but most findings were limited to the investigation of specific cellular markers in the periphery or defined brain regions. In the current study, we aimed to unravel affected molecular pathways/mechanisms in the fear circuitry associated with PTSD. We interrogated a foot shock-induced PTSD mouse model by integrating proteomics and metabolomics profiling data. Alterations at the proteome level were analyzed using in vivo 15N metabolic labeling combined with mass spectrometry in the prelimbic cortex (PrL), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), basolateral amygdala, central nucleus of the amygdala and CA1 of the hippocampus between shocked and nonshocked (control) mice, with and without fluoxetine treatment. In silico pathway analyses revealed an upregulation of the citric acid cycle pathway in PrL, and downregulation in ACC and nucleus accumbens (NAc). Chronic fluoxetine treatment prevented decreased citric acid cycle activity in NAc and ACC and ameliorated conditioned fear response in shocked mice. Our results shed light on the role of energy metabolism in PTSD pathogenesis and suggest potential therapy through mitochondrial targeting.

Key Words: Energy metabolism, Nucleus accumbens, Anterior cingulate cortex, Posttraumatic stress disorder model, Fluoxetine

Introduction

Life-threatening events, such as combat, sexual abuse or natural disasters, are traumatic stressors that can lead to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The core symptoms of PTSD include hyperarousal/hypervigilance, avoidance of trauma-related cues and excessive recall of traumatic memories [1]. PTSD does not develop until weeks to months after trauma exposure. Hence, the long-lasting effect of molecular changes in brain regions involved in stress and traumatic memory (fear circuitry) play an important role in the pathogenesis of PTSD.

Although clinical studies on PTSD have identified dysregulations in endocrine signaling [2,3], neurotransmitter system [4], as well as genetic and epigenetic risk factors [5,6], there is still a lack of global investigations on altered cellular and molecular pathways and biomarkers of fear circuitry involved in PTSD development. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) antidepressants, such as fluoxetine, have been widely used to improve PTSD symptoms in patients [7] and have shown therapeutic efficacy in animal studies [8]. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms affected by fluoxetine in distinct brain regions still remain elusive. A global investigation of molecular pathways associated with fear circuitry with the help of PTSD animal models subjected to fluoxetine treatment can provide useful insights into molecular pathology and treatment efficacy.

For PTSD, a complex and polygenic psychiatric disorder, the integration of different -omics-based methods and systems biology is necessary for a better understanding of disease-related molecular pathways [9,10]. These include nonhypothesis-driven proteomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics methods for the identification of affected pathways and biomarkers.

In the present study, we investigated a previously published PTSD mouse model generated by inescapable foot shocks (FSs) as traumatic stressors [8]. Shocked mice showed PTSD-like symptoms, including conditioned fear response, which was ameliorated upon chronic fluoxetine treatment. To identify dysregulated pathways and therapeutic targets of fluoxetine, we applied proteomics and metabolomics for the analyses of specific mouse model brain regions believed to be involved in PTSD. We focused on brain regions involved in fear circuitry, including the prelimbic cortex (PrL), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), nucleus accumbens (NAc), basolateral amygdala (BLA), central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) and CA1 region of the hippocampus [11,12,13]. For proteomics analysis, 15N metabolically labeled reference material was used for quantitative mass spectrometry [14]. We first identified altered molecular pathways upon FS exposure followed up by an investigation of the fluoxetine rescue effect on the proteome level. We then subjected PrL, ACC, NAc, BLA, CeA, and CA1 punched tissue to targeted polar metabolomics profiling analysis to further corroborate our proteomics findings [15]. Proteomics and metabolomics data were integrated to delineate affected pathways contributing to PTSD-like pathogenesis and fluoxetine targets.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Male C57BL/6NCrl mice, 7-8 weeks old (Charles River GmbH, Sulzfeld, Germany), were housed in groups of four in Makrolon type II cages (23 × 16.5 × 14 cm3) under standard conditions (inverse 12:12-hour light-dark cycle, light off at 7:00, room temperature 23 ± 2°C, humidity 60%) with food and water ad libitum. All experiments were carried out according to the European Community Council Directive 2010/63/EEC and approved by the local government of Upper Bavaria (55.2.1.54-2532-41-09 and 55.2.1.54-2532-141-12). Laboratory animal care and experiments were conducted according to the regulations of the current version of The German Animal Welfare Act.

PTSD Mouse Model and Fluoxetine Treatment

A previously published PTSD mouse model [8,16] was applied by performing fear conditioning (administration of an unsignaled FS in the shock chamber with house light on) during the active phase of the circadian cycle. Mice were conditioned in a Plexiglas cage (16 × 16 × 32 cm3) with a grid harness package (ENV-407, ENV-307A, MED Associates, St. Albans, Vt., USA) connected to a shock generator (Shocker/Scrambler: ENV-414, MED Associates). After 198 s of habituation, animals underwent two electric FSs (1.5 mA, 2 s of length) at moderate illumination (40 lux) with a 60-second interval in between. Animals remained in the shock chamber for another 60 s before being returned to their home cages. Nonshocked (control) mice went through the same procedure, but without receiving FSs.

Fluoxetine, dissolved and administered via drinking water in light-proof bottles (20 mg/kg/day; Ratiopharm GmbH, Ulm, Germany) or vehicle (tap water) treatment was applied to shocked mice 12 h after FSs for 28 days, followed by a 28-day washout period according to previous studies [8]. To assess fluoxetine treatment efficacy, sensitized fear response was evaluated by exposing mice to a neutral tone (60 s of length, 80 dB, 9 kHz) in a neutral cylindrical context on day 28 after FSs. The long-lasting effect of shock application and fluoxetine treatment was assessed after the washout period, by placing mice into the neutral (cylindrical and hexagonal shaped) and shock chambers for contextual fear test for 3 min. In the cylindrical grid chamber, mice were additionally exposed to a neutral tone for 3 min to test sensitized fear (online suppl. fig. S1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000445377). Freezing behavior was defined as immobility except for respiration movements with the head of the animals in a horizontal position according to procedures described previously [8,17]. The entire behavioral session was video-taped for off-line rating by a trained observer who was unaware of the treatment.

Brain Punch Sampling

Mice were euthanized by an overdose of isoflurane (Forene, Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany). Brains were harvested after decapitation and immediately fixed with ice-cold 2-methylbutane (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. For brain punch, brains were dissected with a cryostat (Microm, Walldorf, Germany) up to the appearance of target subregions. Punch specimens were isolated using cylindrical punchers (Fine Science Tools, Heidelberg, Germany) essentially as described [18]. The location and length of the punches were selected based on a stereotaxic atlas [19] described as follows (in mm: starting point rostral-caudal to bregma, punch diameter, punch length): PrL (2.3 mm posterior to bregma, 1.0 mm in diameter, 0.9 mm in length), ACC (0.86, 0.5, 1.0), NAc (1.7, 0.5, 1.0), BLA (-0.8, 0.35, 1.0), CeA (-0.9, 0.5, 0.8), cornu ammonis 1 (CA1) region of the dorsal hippocampus (-1.5, 0.5, 0.8). The dissection site was verified by Nissl histological staining with a stereomicroscope.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Quantitative Proteomics Analysis

Tissue pools (n = 5 for the nonshock-vehicle group, n = 5 for the shock-vehicle group, n = 3 for the shock-fluoxetine group) from each bilaterally punched brain region (PrL, ACC, NAc, BLA, CeA, CA1) were subjected to extraction of cytosolic and membrane-associated proteins [20]. Brain regions from 15N-labeled BL6/C57 mice that cover the punch subregions analyzed were used as reference material [14]. Equal protein amounts of 15N-labeled internal reference standard were added to all samples [14]. 14N/15N protein mixtures representing 50-60 μg were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, fixed and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Biorad, Hercules, Calif., USA). The gel was destained, and each gel lane was cut into 2.5-mm slices (20-22 slices per sample) for tryptic in-gel digestion and peptide extraction, as described previously [14].

Tryptic peptide extracts were dissolved in 0.1% formic acid and subjected to a nanoflow HPLC-2D system (Eksigent, Dublin, Calif., USA) coupled on-line to an LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Prior to peptide separation, samples were on-line desalted for 10 min with 0.1% formic acid at a flow rate of 3 μl/min [Zorbax-C18 (5 μm) guard column, 300 μm × 5 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, Calif., USA]. Desalted peptides were then separated by chromatography [in-house packed Pico-frit column, RP-C18 (3 μm), 75 μm × 15 cm; New Objective, Woburn, Mass., USA]. A gradient of 95% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid from 10 to 45% over 93 min at a flow rate of 200 nl/min was applied for peptide elution. Column effluents were directly injected into the mass spectrometer via a nanoelectrospray ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive mode applying a data-dependent scan switch between MS and MS/MS acquisition. Full scans were recorded in the Orbitrap mass analyzer (profile mode, m/z 380-1,600, resolution R = 60,000 at m/z 400). The top 5 most intense peaks in each scan were fragmented and recorded in the LTQ with a target value of 10,000 ions in the centroid mode. Other MS parameters were set as described previously [14,21].

Protein Identification and Quantitation

Peptides were identified by 14N and 15N database searches using Sequest (v28, implemented in Bioworks v3.3.1; Thermo Fisher Scientific) against a decoy Uniprot mouse protein database (release 2010_02) containing 110,128 entries (including forward and reverse sequences). Enzyme specificity was set to trypsin. Mass accuracy settings were 10 ppm and 1 Da for MS and MS/MS, respectively. Two missed cleavages were allowed, and cysteine carboxyamidomethylation and methionine oxidation were set as fixed and variable modifications, respectively. The filtering parameters for peptide identifications were minimum Delta Cn: 0.08 and Xcorr: 1.90 (z = 1+), 2.7 (z = 2+), 3.50 (z = 3+), and 3.00 (z ≥4+). 15N peptide identification was assessed by a variable modification of −0.99970 Da for lysine and arginine for the frequent shift from 15N monoisotopic to the most intense 15N isotopomer, as described previously [22]. A false discovery rate of 0.1% was set as the filtering criterion for peptide hits using PeptideProphet; 14N and 15N database searches were combined via iProphet, and protein groups were identified by ProteinProphet [23]. Keratin and proteins with one peptide identified were excluded. Relative protein quantification was performed with the ProRata software (v1.0) with default parameter settings [24]. The identified peptides for every 14N/15N were filtered and quantified with a minimum signal-to-noise ratio cutoff of 2, and ambiguous peptides were excluded from further analysis. To correct potential mixing errors during sample preparation, quantification results were normalized by subtracting the median from all log2 ratios of the quantified proteins.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium [25] via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifiers PXD002231, PXD002271, and PXD002272.

Metabolomics Analysis

Punched tissues from 15 mice for each brain region (PrL, ACC, NAc, BLA, CeA, CA1) were pooled into 5 biological replicates (three pooled mouse tissues per analysis) and homogenized (2 min × 1,200 min−1; homogenizer PotterS, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) in 30-fold (W/V) ice-cold 80% methanol (Merck). Homogenates were centrifuged (14,000 g, 10 min) at 4°C, and supernatants were incubated on dry ice for 2 h. Tissue pellets were further disrupted and homogenized with 6-fold (w/v) ice-cold 80% methanol and combined with previous supernatants. Extracts were lyophilized and stored at −80°C for further analysis.

Samples were resuspended in 20 μl liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry grade water; 10 μl were injected and analyzed using a 5500 QTRAP triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB/Sciex, Framingham, Mass., USA) coupled to a Prominence UFLC HPLC system (Shimadzu, Columbia, Md., USA). Samples were delivered to the mass spectrometer via normal-phase chromatography using a 4.6-mm i.d. × 10-cm Amide Xbridge HILIC column (Waters Corp., Milford, Mass., USA) at 350 μl/min. HPLC running buffers and gradients were set as described previously [21]. Some metabolites were targeted in both positive and negative ion modes for a total of 320 SRM transitions using positive/negative polarity switching with previously described mass spectrometer parameter settings [21]. Peak areas from the total ion current for each metabolite SRM transition were integrated using the MultiQuant v2.0 software (AB/Sciex).

Statistics and Data Analysis

Identification of Differentially Expressed Proteins

To compare protein expression levels between two experimental groups, profile likelihoods of both groups were combined via cross-correlation to get a probabilistic estimate of the indirect abundance ratio between two groups. For each protein, a p value for the null hypothesis was derived from the profile likelihood by means of a likelihood ratio test to identify whether the estimated log2 ratio is significantly different from 0. All p values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

In silico Pathway Analysis

To identify altered biological pathways and processes between different mouse groups in distinct brain regions, DE proteins (p < 0.05) were uploaded to DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp) with all quantified proteins as background. Functional enrichment of the KEGG pathway and Gene ontology was acquired, and pathways were considered enriched with a p value <0.05 after the Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

One-Sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test-Based Gene Set Enrichment Analysis and Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and metabolite set enrichment analysis (MSEA) are commonly used statistical methods to identify enriched gene sets or metabolite sets by considering the genome-wide expression profiles of samples from two different groups [26]. The one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test based on GSEA and MSEA is a variation of the typical GSEA/MSEA and uses random walk with permutation to estimate the significance of enrichment. The one-sided KS test-based GSEA/MSEA uses one-sided KS test to estimate whether genes or metabolites involved in the set distribute unevenly in the ranked list (online suppl. fig. S2).

Genes or metabolites are first ranked based on the Pearson's correlation coefficients between their expression profiles and the group distinction pattern, i.e. the pattern using 0 and 1 to distinguish samples from the two different groups. Given a priori-defined sets of genes or metabolites, e.g. the genes or metabolites involved in a given metabolic pathway, the distribution of ranks of these genes or metabolites is compared with the uniform distribution across the list using the one-sided KS test, by trying two different null hypotheses: (1) the rank distribution of the defined gene set is not less than the uniform distribution; (2) the rank distribution of the defined gene set is not greater than the uniform distribution. The significance and the direction of the changes are determined based on the p values for the two null hypotheses.

In this study, the metabolic pathway information, including genes and metabolites that are part of the pathways was obtained from the Small Molecule Pathway Database (http://smpdb.ca/) and Human Metabolome Database (http://www.hmdb.ca/).

Results

Alterations on the Proteome Level in FS-Induced PTSD Mouse Model

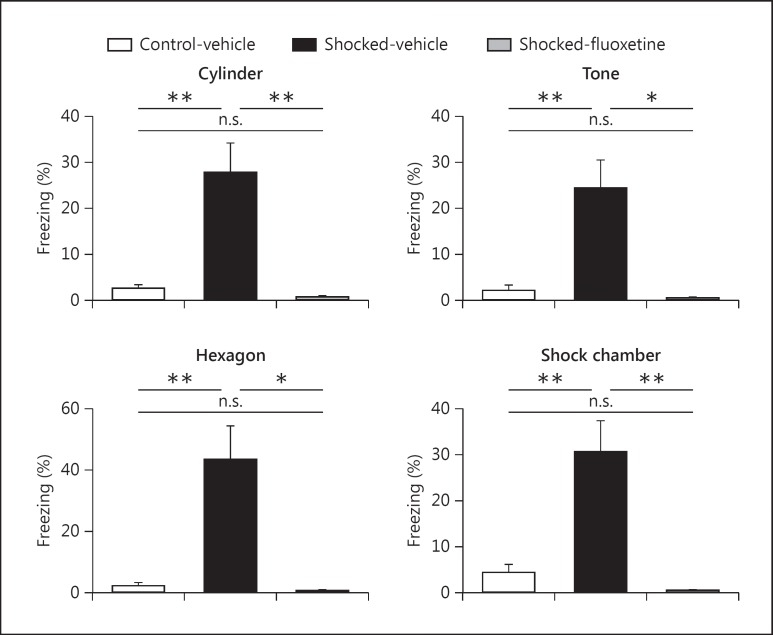

We applied a previously published PTSD mouse model to investigate the molecular changes in the brain [8]. Adult C57BL/6 mice were subjected to two nonescapable electric FSs (1.5 mA, 2 s), followed by a 28-day incubation to develop PTSD-like symptoms. Shocked mice showed significantly higher conditioned fear response when being exposed to neutral contexts (cylindrical and hexagonal shaped plexiglas chambers), neutral tone, and shock context (cubic chamber with metal grid) compared to control (nonshocked) mice (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Shock application and chronic fluoxetine treatment effects on contextual fear response in mice. Mice receiving electric FSs (day 0) showed a significantly higher expression of freezing response when exposed to a neutral context (cylinder chamber, day 56), grid context (hexagon Plexiglas chamber, day 57), neutral tone (day 56), and shock context (cubic chamber with metal grids for shock application, day 57) compared to control (nonshocked) mice. Contextual fear response in shocked mice was ameliorated upon chronic fluoxetine treatment. All comparisons were assessed by one-way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test; n = 5 for the control-vehicle group, n = 5 for the shocked-vehicle group, and n = 3 for the shocked-fluoxetine group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, n.s. = not significant).

A quantitative proteomics platform based on 15N metabolic labeling and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis was used to investigate FS-induced proteome changes in different brain regions involved in fear circuitry [14,22]. 15N-labeled proteins were used as the internal standard for the indirect comparison between control and shocked mice. We punched brain subregions that are involved in fear circuity, including PrL, ACC, NAc, BLA, CeA, and CA1 for further analysis. Due to the limited tissue amount, punched brain tissues from 3-5 mice were pooled. Pooled brain tissues were then extracted for cytosolic and membrane-associated fractions. Nonredundant protein groups were quantified for each brain region by direct comparison between test sample and reference material (online suppl. table S1). Indirect comparison between control and shocked mice revealed significantly differentially expressed (DE) proteins (p < 0.05) after multiple testing correction in both cytosolic and membrane-associated fractions (online suppl. table S1). ACC and NAc showed the strongest alterations in protein abundance, with 154 and 549 DE proteins in ACC, and 223 and 310 DE proteins in NAc in cytosolic and membrane-associated fractions, respectively.

We next investigated enriched cellular processes in different brain regions as described in Experimental Procedures (table 1). A major finding was a significant enrichment of proteins involved in the generation of precursor metabolites and energy metabolism including the citric acid cycle in the membrane-associated fraction of ACC, NAc and PrL (table 1). As a follow-up, we therefore decided to further interrogate FS-induced energy metabolism pathway changes with the help of a metabolomics platform [15].

Table 1.

Enriched molecular pathways in shocked mice

| Brain region | Cellular fraction | Pathway (Gene Ontology/KEGG) | Fold enrichment | Bonferroni | Benjamini | FDR | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrL | cytosolic | GO:0005938~cell cortex | 11.470 | 1.1E–05 | 1.1E–05 | 1.1E–04 | + |

| GO:0044448~cell cortex part | 12.412 | 5.3E–05 | 2.6E–05 | 5.5E–04 | + | ||

| GO:0015629~actin cytoskeleton | 7.930 | 1.5E–03 | 4.9E–04 | 1.5E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0005856~cytoskeleton | 3.893 | 1.6E–03 | 4.1E–04 | 1.7E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0030863~cortical cytoskeleton | 12.594 | 4.0E–03 | 8.0E–04 | 4.2E–02 | + | ||

| membrane-associated | mmu00020:citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 15.565 | 1.1E–03 | 1.1E–03 | 4.5E–02 | + | |

| ACC | cytosolic | GO:0044430~cytoskeletal part | 2.850 | 7.8E–04 | 7.8E–04 | 6.1E–03 | + |

| GO:0007018~microtubule-based movement | 5.954 | 1.2E–02 | 1.2E–02 | 2.7E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0005856~cytoskeleton | 2.316 | 5.1E–03 | 2.5E–03 | 4.0E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0006461~protein complex assembly | 4.253 | 3.8E–02 | 1.9E–02 | 8.4E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0070271~protein complex biogenesis | 4.253 | 3.8E–02 | 1.9E–02 | 8.4E–02 | + | ||

| membrane-associated | GO:0019001~guanyl nucleotide binding | 1.540 | 9.8E–03 | 9.8E–03 | 3.3E–02 | + | |

| GO:0032561~guanyl ribonucleotide binding | 1.540 | 9.8E–03 | 9.8E–03 | 3.3E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0005525~GTP binding | 1.540 | 9.8E–03 | 9.8E–03 | 3.3E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0006091~generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 1.609 | 5.2E–02 | 5.2E–02 | 6.4E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0003924~GTPase activity | 1.850 | 2.8E–02 | 1.4E–02 | 9.6E–02 | – | ||

| NAc | cytosolic | GO:0034622~cellular macromolecular complex assembly | 3.160 | 1.0E–03 | 1.0E–03 | 1.8E–03 | – |

| GO:0065003~macromolecular complex assembly | 3.039 | 1.1E–03 | 5.3E–04 | 1.9E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0034621~cellular macromolecular complex subunit organization | 3.105 | 1.4E–03 | 4.7E–04 | 2.5E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0043933~macromolecular complex subunit organization | 2.943 | 2.0E–03 | 4.9E–04 | 3.5E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0051258~protein polymerization | 6.020 | 3.4E–03 | 6.9E–04 | 6.0E–03 | + | ||

| GO:0003924~GTPase activity | 3.402 | 6.7E–03 | 6.7E–03 | 3.8E–02 | + | ||

| membrane-associated | mmu00020:citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 3.159 | 5.1E–06 | 5.1E–06 | 5.2E–05 | – | |

| GO:0006091~generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 2.102 | 2.7E–06 | 2.7E–06 | 2.9E–06 | – | ||

| GO:0031974~membrane-enclosed lumen | 2.044 | 3.0E–05 | 3.0E–05 | 1.3E–04 | – | ||

| GO:0043233~organelle lumen | 1.973 | 3.2E–04 | 7.9E–05 | 1.3E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0006084~acetyl-CoA metabolic process | 3.500 | 2.5E–03 | 1.3E–03 | 2.7E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0070013~intracellular organelle lumen | 1.949 | 6.7E–04 | 1.3E–04 | 2.8E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0043232~intracellular non-membrane-bound organelle | 1.519 | 7.8E–04 | 1.3E–04 | 3.2E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0043228~non-membrane-bound organelle | 1.519 | 7.8E–04 | 1.3E–04 | 3.2E–03 | |||

| GO:0006099~tricarboxylic acid cycle | 3.482 | 8.4E–03 | 2.8E–03 | 9.2E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0046356~acetyl-CoA catabolic process | 3.482 | 8.4E–03 | 2.8E–03 | 9.2E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0006007~glucose catabolic process | 2.813 | 8.9E–03 | 2.2E–03 | 9.7E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0046365~monosaccharide catabolic process | 2.813 | 8.9E–03 | 2.2E–03 | 9.7E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0019320~hexose catabolic process | 2.813 | 8.9E–03 | 2.2E–03 | 9.7E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0006006~glucose metabolic process | 2.396 | 1.5E–02 | 3.0E–03 | 1.6E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0019318~hexose metabolic process | 2.396 | 1.5E–02 | 3.0E–03 | 1.6E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0016052~carbohydrate catabolic process | 2.639 | 1.8E–02 | 3.0E–03 | 1.9E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0044275~cellular carbohydrate catabolic process | 2.639 | 1.8E–02 | 3.0E–03 | 1.9E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0005996~monosaccharide metabolic process | 2.331 | 2.7E–02 | 4.0E–03 | 3.0E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0006096~glycolysis | 2.857 | 2.8E–02 | 3.6E–03 | 3.1E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0005759~mitochondrial matrix | 2.270 | 6.8E–03 | 9.7E–04 | 2.8E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0031980~mitochondrial lumen | 2.270 | 6.8E–03 | 9.7E–04 | 2.8E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0009109~coenzyme catabolic process | 3.250 | 3.2E–02 | 3.6E–03 | 3.5E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0009060~aerobic respiration | 3.250 | 3.2E–02 | 3.6E–03 | 3.5E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0051187~cofactor catabolic process | 3.088 | 3.3E–02 | 3.3E–03 | 3.6E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0015980~energy derivation by oxidation of organic compounds | 2.386 | 4.5E–02 | 4.2E–03 | 5.0E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0050662~coenzyme binding | 2.257 | 1.5E–02 | 1.5E–02 | 4.5E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0015672~monovalent inorganic cation transport | 6.658 | 1.8E–03 | 1.8E–03 | 4.5E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0006096~glycolysis | 6.053 | 4.8E–03 | 2.4E–03 | 1.2E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0051258~protein polymerization | 8.194 | 6.0E–03 | 2.0E–03 | 1.5E–02 | – | ||

| BLA | cytosolic | GO:0042623~ATPase activity, coupled | 5.644 | 9.9E–03 | 9.9E–03 | 6.9E–02 | – |

| GO:0005874~microtubule | 4.276 | 1.3E–02 | 1.3E–02 | 8.6E–02 | – | ||

| CeA | cytosolic | mmu04540:Gap junction | 9.882 | 6.1E–05 | 6.1E–05 | 1.5E–03 | + |

| GO:0051258~protein polymerization | 17.762 | 5.1E–06 | 5.1E–06 | 2.4E–05 | + | ||

| GO:0043623~cellular protein complex assembly | 12.212 | 1.5E–04 | 7.7E–05 | 7.2E–04 | + | ||

| GO:0007018~microtubule-based movement | 11.493 | 2.6E–04 | 8.6E–05 | 1.2E–03 | + | ||

| GO:0003924~GTPase activity | 7.914 | 3.2E–04 | 3.2E–04 | 3.5E–03 | + | ||

| GO:0007017~microtubule-based process | 7.850 | 9.3E–04 | 2.3E–04 | 4.3E–03 | + | ||

| GO:0006461~protein complex assembly | 9.769 | 9.5E–04 | 1.9E–04 | 4.4E–03 | + | ||

| GO:0070271~protein complex biogenesis | 9.769 | 9.5E–04 | 1.9E–04 | 4.4E–03 | + | ||

| GO:0005874~microtubule | 7.663 | 3.1E–04 | 3.1E–04 | 4.0E–03 | + | ||

| GO:0005198~structural molecule activity | 5.500 | 4.0E–04 | 2.0E–04 | 4.5E–03 | + | ||

| GO:0034622~cellular macromolecular complex assembly | 6.737 | 1.5E–02 | 2.5E–03 | 7.1E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0034621~cellular macromolecular complex subunit organization | 6.737 | 1.5E–02 | 2.5E–03 | 7.1E–02 | + | ||

| GO:0044430~cytoskeletal part | 3.621 | 5.7E–03 | 2.9E–03 | 7.2E–02 | + | ||

| CA1 | cytosolic | GO:0005198~structural molecule activity | 6.424 | 4.2E–09 | 4.2E–09 | 6.3E–08 | – |

| GO:0007017~microtubule-based process | 8.439 | 1.0E–05 | 1.0E–05 | 4.8E–05 | – | ||

| GO:0051258~protein polymerization | 11.763 | 1.4E–04 | 6.8E–05 | 6.3E–04 | – | ||

| GO:0007018~microtubule-based movement | 10.859 | 2.8E–04 | 9.4E–05 | 1.3E–03 | – | ||

| GO:0043623~cellular protein complex assembly | 8.304 | 2.8E–03 | 6.9E–04 | 1.3E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0044430~cytoskeletal part | 3.206 | 1.9E–03 | 1.9E–03 | 2.6E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0005882~intermediate filament | 8.172 | 4.1E–03 | 2.0E–03 | 5.7E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0045111~intermediate filament cytoskeleton | 8.172 | 4.1E–03 | 2.0E–03 | 5.7E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0006461~protein complex assembly | 6.416 | 2.0E–02 | 4.0E–03 | 9.3E–02 | – | ||

| GO:0070271~protein complex biogenesis | 6.416 | 2.0E–02 | 4.0E–03 | 9.3E–02 | – | ||

| membrane-associated | GO:0043209~myelin sheath | 43.667 | 2.9E–03 | 2.9E–03 | 3.8E–02 | – | |

Energy metabolism-related terms are in bold and cytoskeleton-related terms are in italics.

Integration of Proteomics and Metabolomics Profiling Data in Shocked Mice Reveals Altered Energy Metabolisms in NAc and ACC

We applied the one-sided KS test-based GSEA to cytosolic and membrane-associated fraction proteomics data of the different brain regions to enrich affected metabolic pathways. Multiple metabolic pathways were enriched in the shocked mice in distinct brain regions (online suppl. table S2). We found a decrease in citric acid cycle enzyme abundance in the membrane-associated fraction of both ACC and NAc, as well as increased enzyme levels in PrL. These findings were consistent with the DAVID analysis results.

For further verification of these metabolic pathway alterations, we subjected distinct brain region extracts (PrL, ACC, NAc, BLA, CeA, and CA1) from control and shocked mice to metabolomics analyses. A total of 320 metabolites were quantified, of which 268 were assigned to Human Metabolome Database-annotated metabolites (online suppl. table S3). Focusing on the brain regions PrL, ACC, and NAc that had shown metabolic pathway alterations based on the proteomics data, we applied the one-sided KS test-based MSEA to identify significantly altered metabolic pathways in shocked mice (online suppl. table S4). We next employed the permutation-based test by calculating Euclidean distance (De) for rank similarity between GSEA and MSEA analysis. The similarity test showed consistent output results between MSEA and GSEA in the membrane-associated fraction analysis of ACC and NAc (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected false discovery rate <0.1), suggesting that the proteomics and metabolomics data both implicate metabolic pathway alterations in these two brain regions.

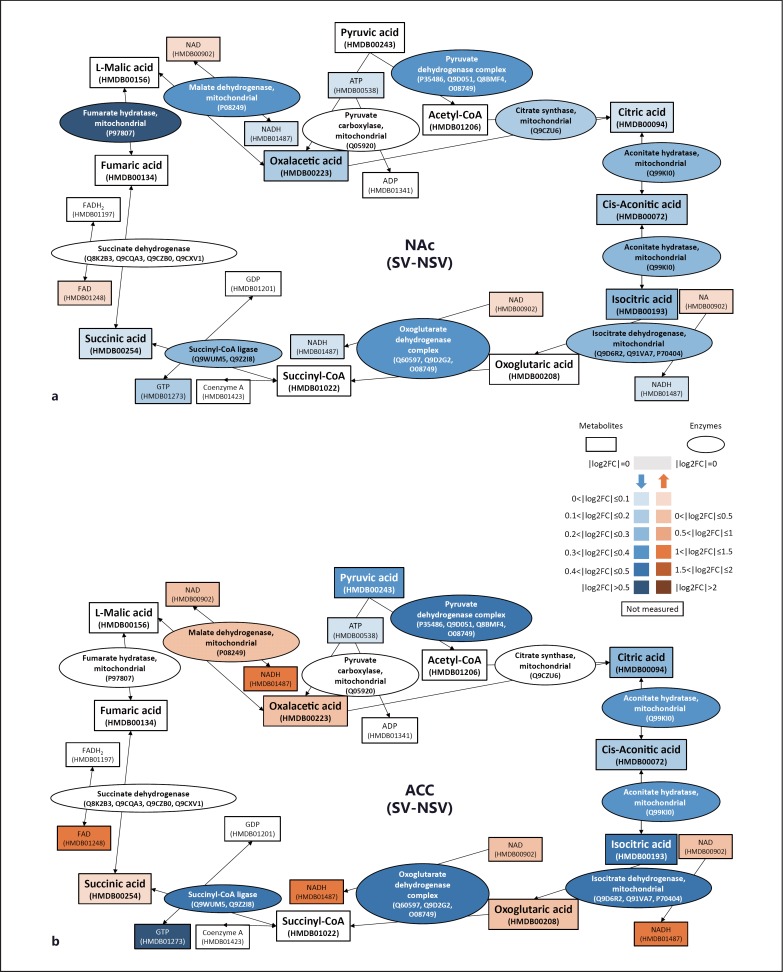

We found a trend for a downregulated citric acid cycle pathway in NAc in shocked mice from MSEA analysis (p = 0.077). The levels of citric acid cycle intermediates including oxalacetic acid, citric acid, aconitic acid, isocitric acid, and succinic acid were decreased (fig. 2a). This was consistent with the proteomics data from DAVID and GSEA analyses that also support downregulation of the citric acid cycle in NAc in shocked mice. Furthermore, MSEA analysis also suggests a weak signal for a decreased citric acid cycle pathway activity in ACC in shocked mice that can in part be explained by the increased abundance of certain metabolites such as NAD and NADH, which in addition to the citric acid cycle are members of several other metabolic pathways. The majority of metabolites involved in the citric acid cycle including pyruvic acid, citric acid, aconitic acid, and isocitric acid were found at lower levels, while only few intermediates (oxolutaric acid, succinic acid and oxalacetic acid) were found with small increases in the ACC of shocked mice (fig. 2b). We then applied the permutation-based test for the longest path of components with a continuous decrease in expression in shocked mice, taking into consideration both the quantified enzymes and metabolites involved in the citric acid cycle in ACC. In the shocked mice, the observation that quantified enzymes and metabolites not only tended to decrease in abundance but also tended to link with each other in one pathway (permutation p = 0.0367) supports the notion that the citric acid cycle in ACC was downregulated in the shocked mice.

Fig. 2.

Altered enzyme and metabolite levels of the citric acid cycle in NAc and ACC in shocked mice. In NAc (a) and ACC (b), enzymes and metabolites involved in the citric acid cycle were downregulated in the shocked mice. Oval- and rectangle-shaped boxes represent enzymes and metabolites of the citric acid cycle, respectively. Red and blue boxes indicate increased and decreased levels, respectively, in the shocked mice compared to control mice. Red and blue box shade intensities represent the level of fold change expressed by log2 ratio (colors refer to the online version only).

Chronic Fluoxetine Treatment Prevents FS-Induced Citric Acid Cycle Proteome Alterations

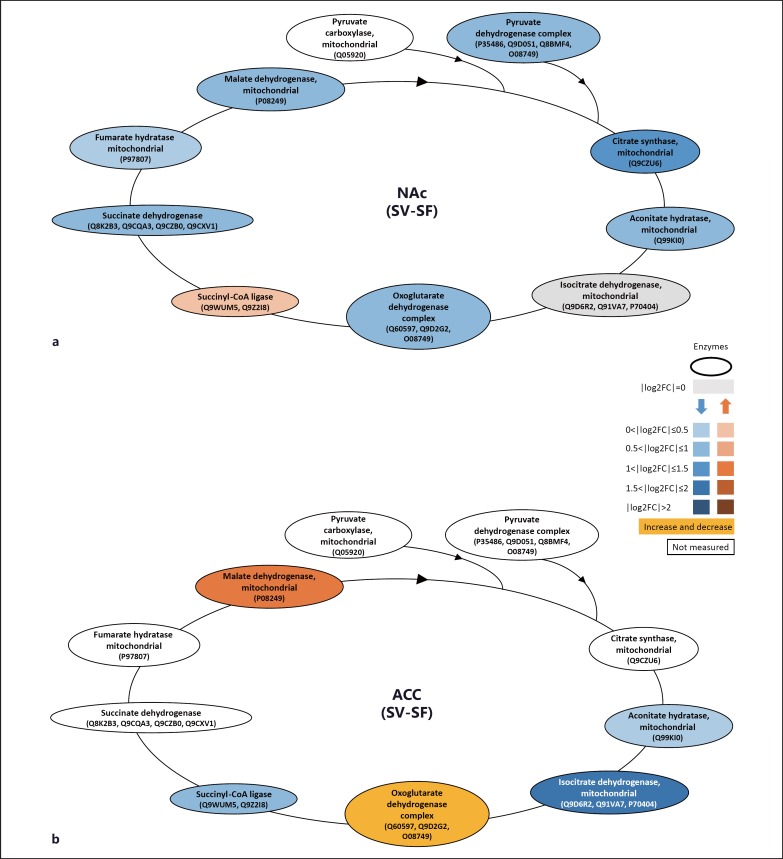

Conditioned fear response, one of the key PTSD-like symptoms, was tested after the fluoxetine washout, and was ameliorated after chronic fluoxetine treatment in shocked mice (fig. 1). We compared brain proteomes between shocked mice treated with fluoxetine and vehicle to investigate molecular changes associated with the fluoxetine rescue. Focusing on the proteins that were affected in the shocked mice, proteomic analysis revealed a rescue effect of fluoxetine treatment for FS-induced altered pathways. With chronic fluoxetine treatment, we found most of the significant FS-induced alterations rescued in the membrane-associated fraction of ACC and CA1 (table 2). Furthermore, fluoxetine treatment increased the expression level of proteins involved in the GO pathway ‘generation of precursor metabolites and energy’ (aconitate hydratase, isocitrate dehydrogenase and succinyl-CoA ligase) which were found decreased in ACC in shocked mice (fig. 3b). In addition, upon fluoxetine treatment, the FS-induced downregulation of most enzymes involved in the citric acid cycle in NAc, including fumarate hydratase, malate dehydrogenase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, aconitate hydratase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, was rescued (fig. 3a; table 2). These findings suggest that fluoxetine treatment affects energy metabolism pathways in NAc, ACC and CA1 associated with FS-induced PTSD-like symptoms.

Table 2.

Rescued pathways upon chronic fluoxetine treatment in shocked mice

| Brain region | DAVID terms | prescueda<0.05 |

|---|---|---|

| ACC | transit peptide | 1.14E–13 |

| membrane | acetylation | 4.93E–13 |

| GO:0005525~GTP binding | 6.67E–11 | |

| gtp binding | 1.90E–10 | |

| GO:0006091~generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 1.36E–08 | |

| iron | 2.86E–06 | |

| GO:0003924~GTPase activity | 2.10E–05 | |

| mmu04540:Gap junction | 0.001281604 | |

| CA1 | transmembrane protein | 1.53E–05 |

| membrane | GO:0007017~microtubule-based process | 0.001953125 |

| GO:0043209~myelin sheath | 0.015625 | |

| microtubule | 0.015625 | |

| myelin | 0.015625 | |

| PIRSF002306:tubulin | 0.03125 | |

| NAc | mmu00020:citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 0.009605408 |

Energy metabolism-related terms are in bold and cytoskeletonrelated terms are in italics.

prescued = p value before multiple test correction.

Fig. 3.

Chronic fluoxetine treatment effect on the enzyme and metabolite levels of the citric acid cycle in NAc and ACC in shocked mice. Proteome comparison of shocked mice with vehicle or fluoxetine treatments revealed lower enzyme levels of the citric acid cycle in both NAc (a) and ACC (b). The results indicate that chronic fluoxetine treatment rescued decreased enzyme expressions of the citric acid cycle in NAc (a) and ACC (b) in shocked mice. Red and blue boxes indicate increased and decreased levels, respectively, in the shocked mice compared to control mice. Red and blue box shade intensities represent the level of fold change expressed by log2 ratio (colors refer to the online version only).

Discussion

In the present study, we have for the first time combined proteomics and metabolomics data of a PTSD mouse model to unravel affected molecular pathways in brain regions believed to be involved in fear circuitry. Our data implicate energy metabolism alterations in NAc and ACC in the shocked mice. Chronic fluoxetine treatment prevents energy metabolism dysregulation in the same brain areas and ameliorates PTSD-like symptoms in shocked mice.

We applied an FS-induced PTSD model using inbred C57BL/6NCrl mice, a strain that is susceptible to PTSD-like symptom development [16,18,27,28,29]. Using a standardized proteomics platform based on 15N metabolic labeling and mass spectrometry, we accurately quantified and identified significantly altered protein expression levels in affected brain regions and enriched altered cellular pathways by in silico pathway analyses. Proteomics findings were further corroborated by targeted metabolite profiling. By integrating proteome and metabolome data, we were able to unravel altered molecular pathways associated with PTSD pathogenesis as well as potential therapeutic targets for fluoxetine treatment.

Mitochondria are involved in intracellular processes regulating neuronal plasticity, survival and signal transduction [30,31,32]. Dysregulated mitochondrial function has been implicated in psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Filiou et al. [14] showed that divergent mitochondrial mechanisms, including energy metabolism, mitochondrial transport and oxidative stress contribute to anxiety-related behaviors in mice. Upon psychological trauma exposure, cellular metabolic responses are activated and chronic inflammation is produced in neurons [33,34]. Persistent dysregulated energy metabolism ultimately leads to bioenergetic impairment and chronic low-grade inflammation, and may result in chronic diseases such as PTSD [33] and schizophrenia [35]. In this regard, Flaquer et al. [36] identified two mitochondrial variants located in the adenosine triphosphate synthase subunit 8 and NADH subunit 5 which were significantly associated with PTSD.

The citric acid cycle produces NADH as a precursor of oxidative phosphorylation and chemical energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate [37]. In our study, we observed an increased expression of proteins involved in the citric acid cycle in PrL in shocked mice (table 1; online suppl. table S1). Persistent PrL activation was reported to be associated with enhanced learned fear expression in female rats [38]. Another study suggested that sustained conditioned responses in PrL correlated with fear extinction failure [39]. Endocannabinoids have been shown to regulate PrL activity by activating cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors and anxiety-like behaviors in rats [40]. Furthermore, CB1 receptors are part of neuronal mitochondria membranes, where they regulate respiration and energy metabolism [41]. Persistent increased energy metabolism that we have observed in PrL may result in neuronal activity and signaling alterations causing exaggerated fear expression in the shocked mouse.

ACC belongs to the prefrontal cortex and interacts with PrL to regulate top-down attention and stimulus-guided action [42] and is involved in emotional control and cognitive functions which are dysregulated in PTSD [43,44]. Previous studies indicate that ACC exhibits diminished activation in response to threat-related events in PTSD [45]. In addition, increased activation in the ventral ACC correlates with symptom improvement after successful treatment of PTSD by cognitive behavioral therapy [46]. Another study reported reduced N-acetylaspartate (NAA) levels in the right ACC of PTSD patients [47]. NAA facilitates energy metabolism in neuronal mitochondria, and decreased NAA levels are associated with reversible neuronal or mitochondrial dysfunction [48,49]. In accordance with previous findings, our proteomics and metabolomics data revealed a downregulation of the citric acid cycle pathway (table 1; fig. 2b), implying decreased mitochondrial/neuronal activity in the ACC of shocked mice.

NAc is associated with cognitive processing, such as motivation and reward [50,51] and plays an important role in anxiety-like behaviors [52,53], emotion [54], and depression [55,56]. Emotional numbing and negative alterations in cognition are among the core PTSD symptoms [1]. Previous studies showed a lower activation of the NAc in PTSD patients, which may be related to decreased motivation and altered reward processing [57]. Similar to our findings in ACC, we observed a decreased expression of proteins and metabolites associated with the citric acid cycle in NAc in shocked mice (table 1; fig. 2a). Proteomics analysis revealed that rats reared with a control condition exhibited decreased expression of proteins involved in the citric acid cycle upon acute stress exposure, while rats reared with environmental enrichment, which produced a protective antidepressant-like phenotype, showed increased protein expression in NAc [58]. Taken together, upon exposure to a stressor, persistent mitochondrial dysfunction results in downstream cellular metabolic changes (e.g. decreased citric acid cycle activity) in NAc and may contribute to the pathogenesis of PTSD.

Fluoxetine is an SSRI antidepressant commonly used for treatment of major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder [7,59,60]. Major psychotherapeutic actions of fluoxetine treatment are reported to impact cortical neurofilament, synaptic remodeling, neurogenesis, and metabolism via 5-HT receptor signaling [61,62,63]. However, treatment with SSRIs has by and large failed to cure PTSD. Nevertheless, this class of compounds is often prescribed to PTSD patients to induce symptomatic relief. This applies to paroxetine in Europe and fluoxetine in North America. One of the reasons why chronic SSRI treatment has failed so far may relate to the time of intervention. In most cases, treatment is initiated once patients are diagnosed with PTSD, which is typically the case weeks to months after trauma. This, however, might be too late for a genuine curative intervention. Indeed, animal experiments indicate that PTSD-like symptoms may become manifest only several weeks after trauma and that this long-term consolidation process has a different neurochemical/molecular signature at early versus late stages [64]. Our data suggest that SSRI treatment starting in the early aftermath of a trauma can prevent the development of a ‘full-blown’ PTSD symptomatology. This conclusion is further supported by the fact that the washout of fluoxetine treatment was not followed by relapse of PTSD-like symptoms. Behavioral changes were accompanied by a ‘reinstatement’ of the citric acid cycle pathways in ACC and NAc of shocked mice after drug washout (fig. 3), indicating a long-lasting effect of fluoxetine treatment on regulating mitochondrial functionality and its preventative effect on PTSD development. Apart from serotonergic neurotransmission, several studies also indicated modulations of mitochondrial functionality after fluoxetine treatment. Upon norfluoxetine (active metabolite of fluoxetine) or other antidepressant treatment, a decreased transmembrane electrochemical gradient generated by the mitochondrial electron transport chain was observed in isolated rat heart mitochondria [65]. Treatment of rats with paroxetine, another SSRI antidepressant, increased mitochondrial respiratory chain in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and cerebral cortex [66]. In line with previous animal studies, Zhao et al. [67] demonstrated that fluoxetine and imipramine treatments regulate energy metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and neurotransmitters in the hippocampus and showed antidepressant effects in a chronic mild stress mouse model. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effect of fluoxetine may improve stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and prevent neurons from cellular metabolism perturbations [68]. Taken together, mitochondria appear to be the target of fluoxetine treatment by its ability to alter energy metabolism and production of amines. The modulation of neuronal energy metabolism might constitute a venue for treating PTSD.

In conclusion, our proteomics and metabolomics data of an FS-induced PTSD mouse model have shown altered energy metabolism in PrL, ACC, and NAc. Furthermore, fluoxetine treatment of PTSD mice rescued protein expression alterations associated with the citric acid cycle in ACC and NAc. A limitation of the current study is the small number of mice (n = 5) per study group. In addition, due to the small amount of tissue mass from the brain punches, proteomic mass spectrometry analyses had to be performed with pooled samples. However, through an integration of proteomics and metabolomics data, we were able to provide novel insights into molecular pathways involved in PTSD and the potential for therapeutic mitochondrial targeting, which most recently is also considered for cancer [69] and neurodegenerative disorder treatments [70]. Mitochondrial involvement has also been suggested in other psychiatric diseases [71,72]. Further studies are needed to find out whether mitochondrial-related alterations are specific for different classes of neurons and elucidate their role in the pathogenesis of distinct mental disorders.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Max Planck Society. We would like to thank Dr. Judith Reichel for assistance with the PTSD mouse model, and Stefan Reckow for help with data processing. Chi-Ya Kao was supported by the Graduate School of Systemic Neurosciences (GSN-LMU).

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders: DSM-5. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yehuda R, Seckl J. Minireview: Stress-related psychiatric disorders with low cortisol levels: a metabolic hypothesis. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4496–4503. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris MC, Compas BE, Garber J. Relations among posttraumatic stress disorder, comorbid major depression, and HPA function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:301–315. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu G, Feder A, Cohen H, Kim JJ, Calderon S, Charney DS, Mathé AA. Understanding resilience. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:10. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt U, Holsboer F, Rein T. Epigenetic aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder. Dis Markers. 2011;30:77–87. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2011-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domschke K. Patho-genetics of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravindran LN, Stein MB. Pharmacotherapy of PTSD: premises, principles, and priorities. Brain Res. 2009;1293:24–39. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegmund A, Wotjak CT. A mouse model of posttraumatic stress disorder that distinguishes between conditioned and sensitised fear. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:848–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitano H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science. 2002;295:1662–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.1069492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barabási AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herry C, Johansen JP. Encoding of fear learning and memory in distributed neuronal circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/nn.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson OJ, Krimsky M, Lieberman L, Allen P, Vytal K, Grillon C. Towards a mechanistic understanding of pathological anxiety: the dorsal medial prefrontal-amygdala ‘aversive amplification’ circuit in unmedicated generalized and social anxiety disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:294–302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70305-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keding TJ, Herringa RJ. Abnormal structure of fear circuitry in pediatric post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:537–545. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filiou MD, Zhang Y, Teplytska L, Reckow S, Gormanns P, Maccarrone G, Frank E, Kessler MS, Hambsch B, Nussbaumer M, et al. Proteomics and metabolomics analysis of a trait anxiety mouse model reveals divergent mitochondrial pathways. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:1074–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan M, Breitkopf SB, Yang X, Asara JM. A positive/negative ion-switching, targeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics platform for bodily fluids, cells, and fresh and fixed tissue. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:872–881. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golub Y, Mauch CP, Dahlhoff M, Wotjak CT. Consequences of extinction training on associative and non-associative fear in a mouse model of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Behav Brain Res. 2009;205:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamprath K, Wotjak CT. Nonassociative learning processes determine expression and extinction of conditioned fear in mice. Learn Mem. 2004;11:770–786. doi: 10.1101/lm.86104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahlhoff M, Siegmund A, Golub Y, Wolf E, Holsboer F, Wotjak CT. AKT/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin signalling within hippocampus and amygdala reflects genetically determined differences in posttraumatic stress disorder like symptoms. Neuroscience. 2010;169:1216–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paxinos G, Franklin K. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiśniewski JR, Nagaraj N, Zougman A, Gnad F, Mann M. Brain phosphoproteome obtained by a FASP-based method reveals plasma membrane protein topology. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:3280–3289. doi: 10.1021/pr1002214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webhofer C, Gormanns P, Reckow S, Lebar M, Maccarrone G, Ludwig T, Pütz B, Asara JM, Holsboer F, Sillaber I, et al. Proteomic and metabolomic profiling reveals time-dependent changes in hippocampal metabolism upon paroxetine treatment and biomarker candidates. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Webhofer C, Reckow S, Filiou MD, Maccarrone G, Turck CW. A MS data search method for improved 15N-labeled protein identification. Proteomics. 2009;9:4265–4270. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller A, Shteynberg D. Software pipeline and data analysis for MS/MS proteomics: the trans-proteomic pipeline. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;694:169–189. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-977-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan C, Kora G, McDonald WH, Tabb DL, VerBerkmoes NC, Hurst GB, Pelletier DA, Samatova NF, Hettich RL. ProRata: A quantitative proteomics program for accurate protein abundance ratio estimation with confidence interval evaluation. Anal Chem. 2006;78:7121–7131. doi: 10.1021/ac060654b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vizcaíno JA, Deutsch EW, Wang R, Csordas A, Reisinger F, Ríos D, Dianes JA, Sun Z, Farrah T, Bandeira N, et al. ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia J, Wishart DS. MSEA: a web-based tool to identify biologically meaningful patterns in quantitative metabolomic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W71–W77. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq329. (Web Server issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrmann L, Ionescu IA, Henes K, Golub Y, Wang NX, Buell DR, Holsboer F, Wotjak CT, Schmidt U. Long-lasting hippocampal synaptic protein loss in a mouse model of posttraumatic stress disorder. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pamplona FA, Henes K, Micale V, Mauch CP, Takahashi RN, Wotjak CT. Prolonged fear incubation leads to generalized avoidance behavior in mice. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegmund A, Dahlhoff M, Habersetzer U, Mederer A, Wolf E, Holsboer F, Wotjak CT. Maternal inexperience as a risk factor of innate fear and PTSD-like symptoms in mice. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:1156–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billups B, Forsythe ID. Presynaptic mitochondrial calcium sequestration influences transmission at mammalian central synapses. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5840–5847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05840.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanden Berghe P, Kenyon JL, Smith TK. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake regulates the excitability of myenteric neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6962–6971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06962.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kann O, Kovács R, Heinemann U. Metabotropic receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling elevates mitochondrial Ca2+ and stimulates oxidative metabolism in hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:613–621. doi: 10.1152/jn.00042.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naviaux RK. Oxidative shielding or oxidative stress? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342:608–618. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.192120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehlert U. Enduring psychobiological effects of childhood adversity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1850–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajasekaran A, Venkatasubramanian G, Berk M, Debnath M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: pathways, mechanisms and implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;48:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flaquer A, Baumbach C, Ladwig KH, Kriebel J, Waldenberger M, Grallert H, Baumert J, Meitinger T, Kruse J, Peters A, et al. Mitochondrial genetic variants identified to be associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e524. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowenstein J. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 13. Boston: Academic Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fenton GE, Pollard AK, Halliday DM, Mason R, Bredy TW, Stevenson CW. Persistent prelimbic cortex activity contributes to enhanced learned fear expression in females. Learn Mem. 2014;21:55–60. doi: 10.1101/lm.033514.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burgos-Robles A, Vidal-Gonzalez I, Quirk GJ. Sustained conditioned responses in prelimbic prefrontal neurons are correlated with fear expression and extinction failure. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8474–8482. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0378-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lisboa SF, Borges AA, Nejo P, Fassini A, Guimarães FS, Resstel LB. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the dorsal hippocampus and prelimbic medial prefrontal cortex modulate anxiety-like behavior in rats: additional evidence. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015;59:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bénard G, Massa F, Puente N, Lourenço J, Bellocchio L, Soria-Gómez E, Matias I, Delamarre A, Metna-Laurent M, Cannich A, et al. Mitochondrial CB1 receptors regulate neuronal energy metabolism. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:558–564. doi: 10.1038/nn.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Totah NK, Jackson ME, Moghaddam B. Preparatory attention relies on dynamic interactions between prelimbic cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:729–738. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodward SH, Shurick AA, Alvarez J, Kuo J, Nonyieva Y, Blechert J, McRae K, Gross JJ. A psychophysiological investigation of emotion regulation in chronic severe posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychophysiology. 2015;52:667–678. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wisdom NM, Pastorek NJ, Miller BI, Booth JE, Romesser JM, Linck JF, Sim AH. PTSD and cognitive functioning: importance of including performance validity testing. Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;28:128–145. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2013.863977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim MJ, Chey J, Chung A, Bae S, Khang H, Ham B, Yoon SJ, Jeong DU, Lyoo IK. Diminished rostral anterior cingulate activity in response to threat-related events in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bryant RA, Felmingham K, Kemp A, Das P, Hughes G, Peduto A, Williams L. Amygdala and ventral anterior cingulate activation predicts treatment response to cognitive behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2008;38:555–561. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schuff N, Neylan TC, Fox-Bosetti S, Lenoci M, Samuelson KW, Studholme C, Kornak J, Marmar CR, Weiner MW. Abnormal N-acetylaspartate in hippocampus and anterior cingulate in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2008;162:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gasparovic C, Arfai N, Smid N, Feeney DM. Decrease and recovery of N-acetylaspartate/creatine in rat brain remote from focal injury. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:241–246. doi: 10.1089/08977150151070856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demougeot C, Marie C, Giroud M, Beley A. N-acetylaspartate: a literature review of animal research on brain ischaemia. J Neurochem. 2004;90:776–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spencer S, Brown RM, Quintero GC, Kupchik YM, Thomas CA, Reissner KJ, Kalivas PW. ɑ2δ-1 signaling in nucleus accumbens is necessary for cocaine-induced relapse. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8605–8611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1204-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wakabayashi KT, Myal SE, Kiyatkin EA. Fluctuations in nucleus accumbens extracellular glutamate and glucose during motivated glucose-drinking behavior: dissecting the neurochemistry of reward. J Neurochem. 2015;132:327–341. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gray JA. Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens: the perspective from aberrations of consciousness in schizophrenia. Neuropsychologia. 1995;33:1143–1153. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salamone JD, Cousins MS, Snyder BJ. Behavioral functions of nucleus accumbens dopamine: empirical and conceptual problems with the anhedonia hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:341–359. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davidson RJ, Irwin W. The functional neuroanatomy of emotion and affective style. Trends Cogn Sci. 1999;3:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shirayama Y, Chaki S. Neurochemistry of the nucleus accumbens and its relevance to depression and antidepressant action in rodents. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4:277–291. doi: 10.2174/157015906778520773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Laplant Q, Graham A, Lutter M, Lagace DC, et al. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sailer U, Robinson S, Fischmeister FP, König D, Oppenauer C, Lueger-Schuster B, Moser E, Kryspin-Exner I, Bauer H. Altered reward processing in the nucleus accumbens and mesial prefrontal cortex of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:2836–2844. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fan X, Li D, Lichti CF, Green TA. Dynamic proteomics of nucleus accumbens in response to acute psychological stress in environmentally enriched and isolated rats. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geller DA, March J. The AACAP Committee on Quality Issues (CQI): Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:98–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guest PC, Knowles MR, Molon-Noblot S, Salim K, Smith D, Murray F, Laroque P, Hunt SP, De Felipe C, Rupniak NM, et al. Mechanisms of action of the antidepressants fluoxetine and the substance P antagonist L- 000760735 are associated with altered neurofilaments and synaptic remodeling. Brain Res. 2004;1002:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang YX, Zhang XR, Zhang ZJ, Li L, Xi GJ, Wu D, Wang YJ. Protein kinase Mζ is involved in the modulatory effect of fluoxetine on hippocampal neurogenesis in vitro. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:1429–1441. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Imoto Y, Kira T, Sukeno M, Nishitani N, Nagayasu K, Nakagawa T, Kaneko S, Kobayashi K, Segi-Nishida E. Role of the 5-HT4 receptor in chronic fluoxetine treatment-induced neurogenic activity and granule cell dematuration in the dentate gyrus. Mol Brain. 2015;8:29. doi: 10.1186/s13041-015-0120-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thoeringer CK, Henes K, Eder M, Dahlhoff M, Wurst W, Holsboer F, Deussing JM, Moosmang S, Wotjak CT. Consolidation of remote dear memories involves corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptor type 1-mediated enhancement of AMPA receptor GluR1 signaling in the dentate gyrus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:787–796. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abdel-Razaq W, Kendall DA, Bates TE. The effects of antidepressants on mitochondrial function in a model cell system and isolated mitochondria. Neurochem Res. 2011;36:327–338. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0331-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scaini G, Maggi D, De-Nês B, Gonçalves C, Ferreira G, Teodorak B, Bez G, Ferreira G, Schuck P, Quevedo J, et al. Activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain is increased by chronic administration of antidepressants. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2011;23:112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2011.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao J, Jung YH, Jang CG, Chun KH, Kwon SW, Lee J. Metabolomic identification of biochemical changes induced by fluoxetine and imipramine in a chronic mild stress mouse model of depression. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8890. doi: 10.1038/srep08890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Currais A. Ageing and inflammation - a central role for mitochondria in brain health and disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;21:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fulda S, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Targeting mitochondria for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:447–464. doi: 10.1038/nrd3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Armstrong LC, Saenz AJ, Bornstein P. Metaxin 1 interacts with metaxin 2, a novel related protein associated with the mammalian mitochondrial outer membrane. J Cell Biochem. 1999;74:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ben-Shachar D, Laifenfeld D. Mitochondria, synaptic plasticity, and schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2004;59:273–296. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(04)59011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stork C, Renshaw PF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder: evidence from magnetic resonance spectroscopy research. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:900–919. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]