Abstract

Purpose

Dermatologic adverse events (dAE) in cancer treatment are frequent with use of targeted therapies. These dAEs have been shown to have significant impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). While standardized assessment tools have been developed for physicians to assess severity of dAEs, there is a discord between objective and subjective measures. The identification of patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments useful in the context of targeted cancer therapies is therefore important in both the clinical and research settings for the overall evaluation of dAEs and their impact on HRQoL.

Methods

A comprehensive, systematic literature search of published articles was conducted by two independent reviewers in order to identify PRO instruments previously utilized in patient populations with dAEs from targeted cancer therapies. The identified PRO instruments were studied to determine which HRQoL issues relevant to dAEs were addressed, as well as the process of development and validation of these instruments.

Results

Thirteen articles identifying six PRO instruments met the inclusion criteria. Four instruments were general dermatology (Skindex-16©, Skindex-29©, Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI], and DIELH-24), and two were symptom-specific (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors-18 [FACT-EGFRI-18] and Hand-Foot Syndrome 14 [HFS-14]).

Conclusions

While there are several PRO instruments that have been tested in the context of targeted cancer therapy, additional work is needed to develop new instruments and to further validate the instruments identified in this study in patients receiving targeted therapies.

Keywords: Targeted cancer therapy, dermatologic adverse events, patient-reported outcomes, health-related quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, as multiple targeted anticancer agents have been introduced, the dermatologic adverse events (dAEs) that accompanied them have become more prevalent and a growing concern in the treatment of patients with cancer [1]. The increased incidence and severity of dAEs with novel therapies, such as acneiform rash, pruritus, xerosis, hair changes, and hand-foot skin reaction (palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome), have underscored the significance of dermatologic evaluation and treatment of these dAEs in patients with cancer. The range of dAEs from cancer therapy has a profound impact on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of the patient, which includes the emotional, psychosocial, and physical well being of patients [2].

For healthcare providers managing patients receiving targeted therapies, the severity of the patient’s skin condition is not easily assessed and communicated. Additionally, the visible degree of the disease often does not correlate with patient distress and impact on quality of life (QoL). The severity of the dAE is therefore related both to its clinical extent and its effects on a patient’s HRQoL. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) is a standardized tool used in oncology trials to document and grade toxic effects of anticancer therapies;[3] however, there are inconsistencies in the severity grading between patients and physicians [4]. Hence, supplementing healthcare provider-graded dAEs with patient self-report of symptoms can help to improve dAE reporting and treatment in both research and clinical settings [5]. Close monitoring, early recognition, and early intervention of dAEs may relieve symptoms and reduce their duration, ultimately leading to improvements in patients’ HRQoL [6].

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments that evaluate HRQoL of cancer patients with dAEs are, therefore, increasingly important in the evaluation of novel therapies in clinical trials. PRO instruments can be categorized as generic, disease-specific, or symptom-specific instruments. Generic instruments evaluate across different diseases and patient populations, while disease or symptom-specific instruments assess the HRQoL effects of a particular disease or its therapies, respectively. To select the proper PRO instrument, one should consider the instrument content, quality, and its development and validation [7] and the intended use (e.g. clinical care or research purposes). To identify available PRO instruments in the treatment of oncology patients with dAEs from targeted cancer therapy, we conducted a systematic review of the literature. The objectives were to: (1) identify PRO instruments designed to measure HRQoL in patients with dAEs from targeted cancer therapy; and (2) evaluate the development, content, and psychometric properties of these instruments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comprehensive electronic literature search of published articles was conducted in the following databases: MEDLINE via PubMED, PsychINFO (Psychological Abstracts) via OVID, Cochrane via Wiley, EMBASE via Elsevier, CINAHL via EBSCO, and HAPI (Health and Psychosocial Instruments) via OVID. There was no date restriction and each database was searched in its entirety. Grey literature sources were also searched and reviewed to include SCOPUS and BIOSIS Previews® for conference proceedings and meeting abstracts. There were no limits placed on language or publication type. Controlled vocabulary (MeSH, PsycINFO Subject Headings, CINAHL Headings, EMTREE) and keywords were used with the strategy including key words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms (Appendix I). Further manual search of the reference lists of the relevant studies was also performed. Four broad concept categories were searched, and results were combined using the appropriate Boolean operators (AND, OR). The broad categories included: patient reported outcomes, QoL, skin conditions, and targeted cancer therapies.

Two independent reviewers examined the titles and abstracts of all articles. The full text of any potentially relevant article was examined using the inclusion criteria: (1) patient population with dAEs from targeted anticancer agents; and (2) study describing a PRO instrument measuring HRQoL or patient satisfaction. Exclusion criteria were: (1) articles that did not include a PRO instrument of HRQoL or patient satisfaction; (2) articles that used generic or ad hoc questionnaires (i.e. without published evidence of a development or validation process); and (3) no PRO outcomes of interest related to our patient population.

The identified PRO instruments were studied to determine which HRQoL issues relevant to dAEs were addressed. All instruments were investigated to obtain information on the original development and validation process. The instruments were assessed for adherence to guidelines of the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust and US Food and Drug Administration [8].

RESULTS

The search identified 1,124 articles (Figure I). The full-text of 73 articles were reviewed in detail for eligibility. Four additional articles were identified via manual search. Thirteen articles (Table I) identifying six instruments (Table II) met the inclusion criteria. Four instruments were generic (Skindex-16© [2,9–11], Skindex-29© [12], Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI] [6,13], Deutsches Instrument zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität bei Hauterkrankungen [DIELH-24] [14]) and two were symptom-specific Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors-18 [FACT-EGFRI-18] [15,16] and Hand-Foot Syndrome 14 [HFS-14][17–19]).

Figure I.

Flow diagram of search strategy

Table I.

Previous Studies with PRO Instruments in Targeted Cancer Therapy

| Publication | PRO Instrument | Population | Targeted Therapies | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joshi SS. Cancer, 2010[2] | Skindex-16© | 67 | EGFRI |

|

| Nardone B. J Drugs Dermatol, 2012[9] | Skindex-16© | 23 | Sorafenib, Sunitinib |

|

| Rosen AC. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2013[10] | Skindex-16© | 163 (targeted therapy), 120 (non-targeted therapy | EGFRI, mTOR, TKIs |

|

| Jatoi A. Cancer, 2008 [11] | Skindex-16© | 61 | EGFRI |

|

| Andreis F. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2010 [12] | Skindex-29© | 45 | EGFRI |

|

| Lacouture ME. J Clin Oncol, 2010 [6] | DLQI | 95 | EGFRI |

|

| Osio A. Br J Dermatol, 2009 [13] | DLQI | 15 | EGFRI |

|

| Unger K. Z Gastroenterol, 2013 [14] | DIELH-24 | 20 (Chemotherapy + Anti-EGFR), 20 (Chemotherapy) | EGFRI |

|

| Wagner LI. Support Care Cancer, 2013[15] | FACT-EGFRI-18 | 20 | EGFRI |

|

| Boers-Doets CB. Support Care Cancer, 2013[16] | FACT-EGFRI-18 | 10 (patients with dAEs due to Anti-EGFR therapy) | EGFRI |

|

| Sibaud V. Oncologist, 2011[17] | HFS-14 | 43 (with Hand-Foot Syndrome) | Sorafenib, Sunitinib |

|

| Taieb C. Value in Health, 2009 [18] | HFS-14 | 20 (with Hand-Foot Syndrome) | Sorafenib, Sunitinib |

|

| Teo YL. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2014[19] | HFS-14 | 24 | Sunitinib |

|

CTCAE= Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; EGFRI=Epidermal Growth Receptor Inhibitor; HFSR= hand-foot skin reaction; QoL= Quality of life

Table II.

Comparison of PRO Instruments Previously Tested in Targeted Cancer Therapy

| PRO Instrument | Type of Instrument | Number of Questions | Validation Status for Targeted Therapies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skindex-16© | Generic | 16 | Validated |

| Skindex-29© | Generic | 29 | Validated |

| DLQI | Generic | 10 | Validated |

| DIELH-24 | Generic | 24 | Not Validated |

| FACT-EGFRI-18 | Symptom-Specific | 18 | In Process |

| HFS-14 | Symptom-Specific | 14 | Validated |

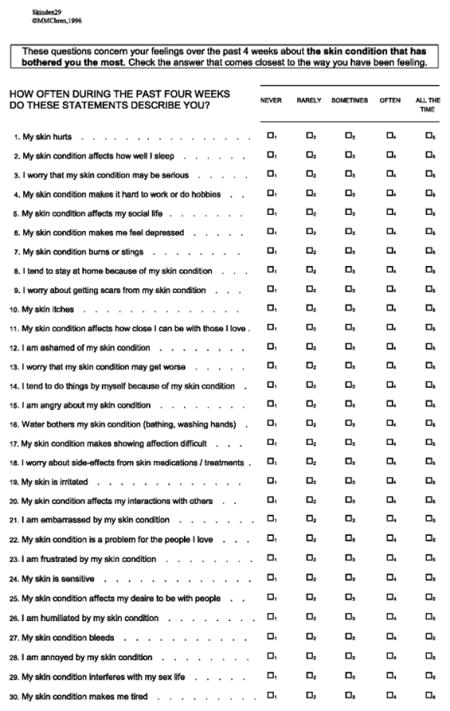

The Skindex-29© is a validated, self- administered, 29-item questionnaire (Appendix II). The instrument uses open-ended questions to assess how bothered a patient is by his/her skin condition on a 5-point scale (1–5) from “Never” (1) to “All the Time” (5). Results of the Skindex-29© are reported as 3-scale scores assessing emotions, physical symptoms, and functioning. Scale scores are the means of responses to the items included in the scale, range from 29 to 116, and higher scores indicate worse HRQoL. An Italian version of the instrument was previously utilized to measure the impact of EGFRI skin toxicity on HRQoL in colon cancer patients [12]. More comprehensive than the later developed Skindex-16©, the Skindex-29© is more useful in understanding detailed effects of a condition on HRQoL [21]. Since it has been available for clinical researchers for longer than the Skindex-16©, the Skindex-29© also has a more expansive database of typical scores for a variety of skin conditions [21]. However, this increased detail comes with the disadvantage of a longer survey, which may be a disadvantage in studies where respondent burden is a concern. Another disadvantage of the Skindex-29© is the lack of questions pertaining to hair, nails, or mucous membranes, which are common sites of toxicity for targeted cancer therapies [15].

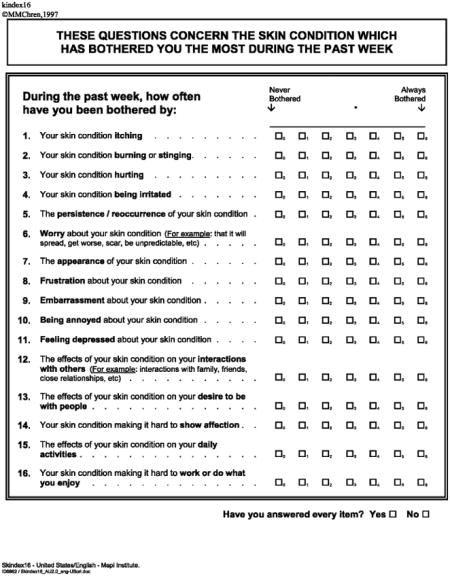

Developed from the Skindex-29© questions with the best performance characteristics, the Skindex-16© is a 16-question survey that has been validated to accurately and sensitively measure how much a patient is bothered by a skin condition (Appendix III). It uses questions to assess how bothered a patient is by his/her skin condition on a 7 point scale (0–6) from “Never bothered” (0) to “Always bothered” (6), and assesses HRQoL as it pertains to three domains of life: symptoms, emotions and functioning. The Skindex-16© has been shown to have good reproducibility (r=0.88–0.90) [20]. The survey has been tested with several targeted therapies, including EGFRIs and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Table I). These studies showed significant correlation between the survey’s HRQoL scores and other outcome measures, including severity grading and NCI CTCAE scores [2,9–11]. Because the Skindex-16© assesses how much a side effect “bothers” the respondent rather than “how often” such a side effects occurs (as in the Skindex-29©), the instrument may more directly assess side effects on HRQoL [21]. In addition, the single-page length of this survey is helpful in studies where respondent burden may be troublesome [21]. However, similar to the Skindex-29©, the Skindex-16© does not specifically address toxicities of the hair, nails, or mucous membranes.

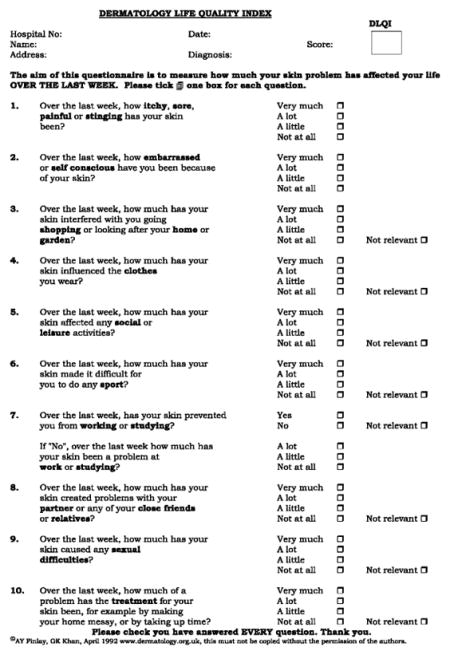

The DLQI was the first dermatology-specific HRQoL instrument [22]. It is a 10-question survey assessing symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work/school, personal relationships, and treatment within the last week (Appendix IV). It has been validated and found to be reliable in adult patients (>18 years old) with different skin diseases. Each question has four alternative responses scored from 0 to 3: ‘not at all (0),’ ‘a little (1),’ ‘a lot (2),’ or ‘very much (3).’ The scores are summed and overall scores range from 0 (no impairment) to 30 (maximum impairment). In five studies that looked at internal consistency for the DLQI, Cronbach’s α scores ranged from 0.83 to 0.93 [22,23]. The instrument was previously utilized to examine differences in decrease in HRQoL from panitumumab-related skin toxicities in patients receiving pre-emptive skin dermatologic treatment compared to reactive dermatologic treatment [6]. The DLQI has also been used to measure impact of long-term EGFRI side effects on HRQoL [13]. As the first dermatology-specific HRQoL instrument, a major strength of the DLQI is its vast amount of available clinical research data. In addition, the DLQI was purposefully designed to be very simple to use and score [24]. Score interpretation is also relatively easy (e.g. greater than 10 generally implies a very severe impact) [24]. However, like the Skindex instruments, the DLQI does not address hair, nail, or mucous membrane toxicities.

The Deutsches Instrument zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität bei Hauterkrankungen (DIELH-24), or German Instrument for Recording Quality of Life in Skin Diseases, is a HRQoL instrument previously shown to possess internal consistency, reliability, and validity in the German language for general skin complaints and atopic dermatitis [25]. Recently it was used in the setting of cetuximab therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer [14]. A major disadvantage of this instrument is its current availability only in German.

The FACT-EGFRI-18 is an 18-question survey that assesses the physical, emotional, social, and functional impact of skin, nail, and hair toxicities from EGFRI treatment on patients’ HRQoL (Appendix V). It uses statements and asks patients to use a 5-point scale, from “Not at all” (0) to “Very Much” (4), to indicate how that statement applies to them. Instrument development was accomplished by interviewing patients and providers, and there is currently a trial through Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) that has FACT-EGFRI-18 validation as a secondary objective. To date, patient and expert input has been solicited for item generation, selection, and refinement with further validation underway [15,16]. The major strength of the FACT-EGFRI-18 is its incorporation of questions related to hair, nails, and mucous membrane toxicities [15]. One weakness of this instrument is the lack of substantial clinical research data for comparison since the survey has just recently been developed. Another limitation of the FACT-EGFRI-18 is its application to only EGFRI side-effects.

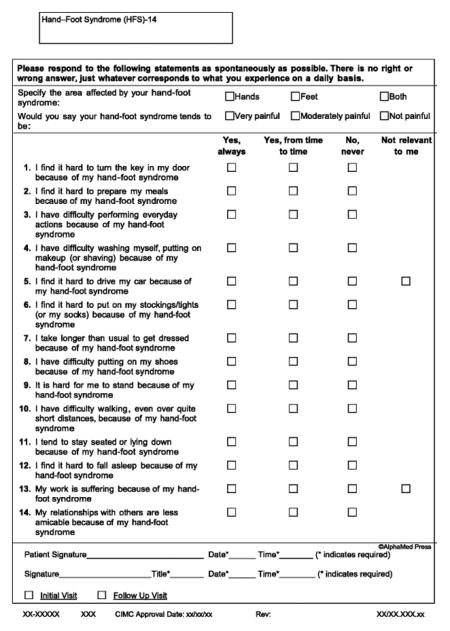

The Hand-Foot Syndrome 14 (HFS-14) is a QoL scale for patients experiencing chemotherapy-associated hand-foot syndrome (HFS) and targeted therapy-associated hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR). This instrument measures severity and impact on patients. The HFS-14 is a 14-item questionnaire that has been validated to measure how HFS impairs a patient’s HRQoL (Appendix VI). It uses statements that may be true for patients with HFS and each item is scored on a three-point Likert scale: 0, “No, never”; 1, “Yes, from time to time”; 2, “Yes, always.” Patients are also asked if their HFS affects their hands, feet, or both, and to assess their overall level of pain (not painful, moderately painful, and very painful). While Skindex-16© and FACT-EGFRI-18 focus on the patient’s experiences with dAEs in the past week, the HFS-14 asks patients to base their answers on experiences within the past day. This tool demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α>0.9) and had good correlation with other validated tools (DLQI, Skindex-16©, and NCI CTCAE clinical grading) [17]. A primary weakness of HFS-14 is its limitation to only HFS toxicities. In addition, there is limited published data related to HFS-14 survey results at this time.

DISCUSSION

With the increased use of novel chemotherapeutic agents, dAEs are increasingly more common [1]. Historically, alopecia and mucositis were the most common dAE associated with chemotherapy. With newer target-specific therapies, other dAEs including papulopustular (acneiform) rash, hand-foot skin reaction, xerosis, pruritus, hair changes (including trichomegaly, hypertrichosis, hair curling), pigmentary changes, mucosal toxicities, fissures of fingertips and toes, and nail changes (paronychia, onycholysis) have become more prominent [26]. Such dAEs can often necessitate treatment interruption or dose modification, and may also significantly impact HRQoL [27]. A recent survey study showed that target-specific cancer therapies are associated with a poorer HRQoL compared to traditional non-targeted cancer therapies [10]. In an interview study of patients receiving EGFRIs, patients identified physical discomfort – specifically, the sensations of pain, burning, skin sensitivity – as having the largest impact on HRQoL, resulting in worry, frustration, and depression [28]. In particular, younger patients with dAEs from cancer treatment appear to have a significantly greater decrease in HRQoL compared to older patients who experience similar toxicities [2].

The previous lack of systematic grading systems for dAEs has led to the recent development of standardized systems to evaluate these toxicities in both the research and clinical setting. In particular, the NCI CTCAE was developed as a standardized tool used in oncology trials to document and grade toxic effects of anticancer therapies [26]. However, patients and physicians often disagree as to the severity of dAEs [16]. It is also difficult for healthcare providers to objectively measure the effect of a particular dAE on a patient’s HRQoL. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a strategy to capture the patient’s understanding of the severity of dAEs and their effects on HRQoL.

In this study, we have reviewed the PRO instruments that can be utilized in research and clinical settings to objectively assess the effects of dAEs on patient HRQoL. Our systematic review of the literature identified six available PRO instruments that have been used to measure HRQoL in patients with dAEs from targeted cancer therapy. PRO instruments are useful as a means to acknowledge the discrepancy between patient and clinicians’ understanding of dAEs, and as a supplement to grading systems, such as NCI CTCAE, in evaluating the overall effect of dAEs on patient well being. Furthermore, patients with cancer are generally receptive to repeated HRQoL assessment, making implementation of PRO instruments feasible [29]. Routine use of these instruments may encourage patients to address how dAEs affect their physical, emotional, and psychosocial well being. In doing so, clinicians can intervene earlier to improve symptoms and reduce the length of dAEs, ideally leading to improvements in patients’ HRQoL and avoid unnecessary modifications in or cessation of cancer treatment [6]. Future research is required to assess whether the incorporation of HRQoL tools in routine clinical practice would lead to less dAEs. In another study, the investigators evaluated the differences in plasma sunitinib and metabolite concentrations between patients with and without dAEs. [19] In this study, hand and feet complaints were assessed utilizing HFS-14. This demonstrates another utility of PRO instruments: to correlate clinical outcomes with biochemical findings.

There are several limitations to be acknowledged in this review. While our search was only limited to targeted therapies, there are other PRO instruments developed for the measurement of HRQoL in dermatologic patients [30]. Although these PRO instruments have not been tested specifically in targeted cancer therapy, they are additional resources that the clinician or scientific investigator may consider for application and further validation in the context of targeted cancer therapy.

Targeted therapies are gaining popularity in the management of cancers ranging from chronic myeloid leukemia to renal cell carcinoma. Much evidence suggests that patients’ HRQoL may be affected by the dAEs of these agents. As there is often a discord between objective and subjective measures of dAEs in clinical practice, there may be a need to incorporate appropriate PRO instruments to accurately assess these dAEs from the patient’s perspective. This study has reviewed the PRO instruments that can currently be utilized in research and clinical settings to objectively assess the effects of dAEs on patient HRQoL.

Appendix I. Search Strategies and Terms Used

| Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) | Keyword terms |

|---|---|

|

| |

| (“Questionnaires”[Mesh] OR “Weights and Measures”[Mesh] OR “Health Care Surveys”[Mesh] AND (“Quality of Life”[Mesh] OR “Quality-Adjusted Life Years”[Mesh] OR “Health Status”[Mesh] OR “Personal Satisfaction”[Mesh] OR “Patient Satisfaction”[Mesh] OR “Patient Compliance”[Mesh] OR “Pain”[Mesh] OR “Body Image”[Mesh] OR “Social Adjustment”[Mesh] OR “Social Behavior” [Mesh] OR “Shyness”[Mesh] OR “Social Distance”[Mesh] OR “Social Isolation”[Mesh] OR “Fear” [Mesh] OR “Frustration”[Mesh] OR “Personal Autonomy”[Mesh] OR “Self Concept”[Mesh] OR “Adaptation, Psychological”[Mesh] OR “Stress, Psychological”[Mesh] OR “Emotions”[Mesh]) AND “Skin Diseases”[Mesh] OR “Epidermal Necrolysis, Toxic”[Mesh] AND (“Molecular Targeted Therapy”[Mesh] OR “temsirolimus” [Supplementary Concept] OR “lenalidomide” [Supplementary Concept] OR “Aromatase Inhibitors”[Mesh] OR “anastrozole” [Supplementary Concept] OR “exemestane” [Supplementary Concept] OR “letrozole” [Supplementary Concept] OR “dasatinib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “4-methyl-N-(3-(4-methylimidazol-1-yl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-((4-pyridin-3-ylpyrimidin-2-yl)amino)benzamide” [Supplementary Concept] OR “bosutinib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “trastuzumab” [Supplementary Concept] OR “pertuzumab” [Supplementary Concept] OR “lapatinib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “gefitinib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “erlotinib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “cetuximab” [Supplementary Concept] OR “panitumumab” [Supplementary Concept] OR “everolimus” [Supplementary Concept] OR “N-(4-bromo-2-fluorophenyl)-6-methoxy-7-((1-methylpiperidin-4-yl)methoxy)quinazolin-4-amine” [Supplementary Concept] OR “PLX4032” [Supplementary Concept] OR “crizotinib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “vorinostat” [Supplementary Concept] OR “romidepsin” [Supplementary Concept] OR “bexarotene” [Supplementary Concept] OR “alitretinoin” [Supplementary Concept] OR “Tretinoin”[Mesh] OR “bortezomib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “carfilzomib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “10-propargyl-10-deazaaminopterin” [Supplementary Concept] OR “sunitinib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “pazopanib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “regorafenib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “cabozantinib” [Supplementary Concept] OR “rituximab” [Supplementary Concept] OR “alemtuzumab” [Supplementary Concept] OR “ofatumumab” [Supplementary Concept] OR “ipilimumab” [Supplementary Concept] OR “iodine-131 anti-B1 antibody” [Supplementary Concept] OR “ibritumomab tiuxetan” [Supplementary Concept] OR “denileukin diftitox” [Supplementary Concept] OR “cAC10-vcMMAE” [Supplementary Concept]) | (patient-reported outcomes OR PROM OR PROMs OR PRO OR PROs OR patient-reported outcomes OR questionnaire OR instrument OR instruments OR measure OR measures OR scale OR scales OR survey OR surveys) AND (quality of life OR QOL OR HRQL OR HRQOL OR quality adjusted life years OR QALY OR health status OR functional status OR well-being OR personal satisfaction OR patient satisfaction OR patient compliance OR pain OR disability OR disabilities OR disabled OR body image OR social function OR social behavior OR social behaviour OR shyness OR social distance OR social isolation OR fear OR frustration OR autonomy OR self-concept OR adaptation OR adjustment OR coping OR stress OR emotion) AND (skin conditions OR skin side effects OR skin irritation OR skin reactions) AND (targeted cancer therapies OR molecularly targeted drugs OR molecularly targeted therapies OR EGFR inhibitors OR temsirolimus OR lenalidomide OR Aromatase inhibitors OR Anastrozole OR Arimidex OR Exemestane OR Aromasin OR Letrozole OR Femara OR Dasatinib OR Sprycel OR Nilotinib OR Tasigna OR Bosutinib OR Bosulif OR Trastuzumab OR Herceptin OR Pertuzumab OR Perjeta OR Lapatinib OR Tykerb OR Gefitinib OR Iressa OR Erlotinib OR Tarceva OR Cetuximab OR Erbitux OR Panitumumab OR Vectibix OR Torisel OR Everolimus OR Afinitor OR Vandetanib OR Caprelsa OR Vemurafenib OR Zelboraf OR Crizotinib OR Xalkori OR Vorinostat OR Zolinza OR Romidepsin OR Istodax OR Bexarotene OR Targretin OR Alitretinoin OR Panretin OR Tretinoin OR Vesanoid OR Bortezomib OR Velcade OR Carfilzomib OR Kyprolis OR Pralatrexate OR Folotyn OR Bevacizumab OR Avastin OR Ziv-aflibercept OR Zaltrap OR Sorafenib OR Nexavar OR Sunitinib OR Sutent OR Pazopanib OR Votrient OR Regorafenib OR Stivarga OR Cabozantinib OR Cometriq OR Rituximab OR Rituxan OR Alemtuzumab OR Campath OR Ofatumumab OR Arzerra OR Ipilimumab OR Yervoy OR cTositumomab OR 131I-tositumomab OR Bexxar OR Ibritumomab tiuxetan OR Zevalin OR Denileukin diftitox OR Ontak OR Brentuximab vedotin OR Adcetris) |

Appendix II. Skindex-29©[21]

Appendix III. Skindex-16©[21]

Appendix IV. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)[22]

Appendix V. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors-18 (FACT-EGFRI-18)[15]

Appendix VI. Hand-Foot Syndrome 14 [HFS 14][17]

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST AND SOURCES OF FUNDING

There were no sources of funding used in this study. The authors have full control of the primary data, which is available to the journal at their request for review.

Dr. Roeland has a consultant role with Cellulitix.

Dr. Choi has received remuneration from Onyx Pharmaceuticals and has a consultant role with Biotest AG.

Dr. Bryce has a consultant role with AstraZeneca and Roche.

Dr. Gerber has a consultant role with Galderma International. He is also receiving research funding from Hoffman La Roche.

Dr. Lacouture has a consultant role with AstraZeneca, Roche, Bayer, Janssen, Exelixis, Advancell, BMS, Amgen, and Genentech. He is also receiving research funding from Berg, Roche and BMS.

References

- 1.Agha R, Kinahan K, Bennett CL, Lacouture ME. Dermatologic challenges in cancer patients and survivors. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2007;21(12):1462–1472. discussion 1473, 1476, 1481 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi SS, Ortiz S, Witherspoon JN, Rademaker A, West DP, Anderson R, Rosenbaum SE, Lacouture ME. Effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced dermatologic toxicities on quality of life. Cancer. 2010;116(16):3916–3923. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen A, Acharya A, Setser A. Dermatologic Principles and Practice in Oncology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013. Grading Dermatologic Adverse Events in Clinical Trials Using CTCAE v4.0; pp. 47–59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basch E, Iasonos A, McDonough T, Barz A, Culkin A, Kris MG, Scher HI, Schrag D. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: results of a questionnaire-based study. The lancet oncology. 2006;7(11):903–909. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(06)70910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basch E. Beyond the FDA PRO guidance: steps toward integrating meaningful patient-reported outcomes into regulatory trials and US drug labels. Value in health: the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2012;15(3):401–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.03.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B, Pillai MV, Shearer H, Iannotti N, Xu F, Yassine M. Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-Emptive Skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(8):1351–1357. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.21.7828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cano SJ, Klassen A, Pusic AL. The science behind quality-of-life measurement: a primer for plastic surgeons. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009;123(3):98e–106e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819565c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, Lohr KN, Patrick DL, Perrin E, Stein RE. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2002;11(3):193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nardone B, Hensley JR, Kulik L, West DP, Mulcahy M, Rademaker A, Lacouture ME. The effect of hand-foot skin reaction associated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib on health-related quality of life. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD. 2012;11(11):e61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen AC, Case EC, Dusza SW, Balagula Y, Gordon J, West DP, Lacouture ME. Impact of dermatologic adverse events on quality of life in 283 cancer patients: a questionnaire study in a dermatology referral clinic. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2013;14(4):327–333. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jatoi A, Rowland K, Sloan JA, Gross HM, Fishkin PA, Kahanic SP, Novotny PJ, Schaefer PL, Johnson DB, Tschetter LK, Loprinzi CL. Tetracycline to prevent epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced skin rashes: results of a placebo-controlled trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N03CB) Cancer. 2008;113(4):847–853. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreis F, Rizzi A, Mosconi P, Braun C, Rota L, Meriggi F, Mazzocchi M, Zaniboni A. Quality of life in colon cancer patients with skin side effects: preliminary results from a monocentric cross sectional study. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2010;8:40. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osio A, Mateus C, Soria JC, Massard C, Malka D, Boige V, Besse B, Robert C. Cutaneous side-effects in patients on long-term treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. The British journal of dermatology. 2009;161(3):515–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unger K, Niehammer U, Hahn A, Goerdt S, Schumann M, Thum S, Schepp W. Treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer with cetuximab: influence on the quality of life. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie. 2013;51(8):733–739. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner LI, Berg SR, Gandhi M, Hlubocky FJ, Webster K, Aneja M, Cella D, Lacouture ME. The development of a Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) questionnaire to assess dermatologic symptoms associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (FACT-EGFRI-18) Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21(4):1033–1041. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1623-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boers-Doets CB, Gelderblom H, Lacouture ME, Epstein JB, Nortier JW, Kaptein AA. Experiences with the FACT-EGFRI-18 instrument in EGFRI-associated mucocutaneous adverse events. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21(7):1919–1926. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1752-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibaud V, Dalenc F, Chevreau C, Roche H, Delord JP, Mourey L, Lacaze JL, Rahhali N, Taieb C. HFS-14, a specific quality of life scale developed for patients suffering from hand-foot syndrome. The oncologist. 2011;16(10):1469–1478. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taieb C, Sibaud V. PCN82 HFS 14: A Specific Quality of Life Instrument for Patients with Hand-Foot Syndrome. Value in Health. 2009;12(3):A52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teo YL, Chong XJ, Chue XP, Chau NM, Tan MH, Kanesvaran R, Wee HL, Ho HK, Chan A. Role of sunitinib and SU12662 on dermatological toxicities in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients: in vitro, in vivo, and outcomes investigation. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2014;73(2):381–388. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, Sands LP. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2001;5(2):105–110. doi: 10.1007/s102270000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chren MM. The Skindex instruments to measure the effects of skin disease on quality of life. Dermatologic clinics. 2012;30(2):231–236. xiii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis V, Finlay AY. 10 years experience of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) The journal of investigative dermatology Symposium proceedings/the Society for Investigative Dermatology, Inc [and] European Society for Dermatological Research. 2004;9(2):169–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.09113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finlay AY, Basra MK, Piguet V, Salek MS. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI): a paradigm shift to patient-centered outcomes. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2012;132(10):2464–2465. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schafer T, Staudt A, Ring J. German instrument for the assessment of quality of life in skin diseases (DIELH). Internal consistency, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity and responsiveness. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2001;52(7):624–628. doi: 10.1007/s001050170102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen AP, Setser A, Anadkat MJ, Cotliar J, Olsen EA, Garden BC, Lacouture ME. Grading dermatologic adverse events of cancer treatments: the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.0. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012;67(5):1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boone SL, Rademaker A, Liu D, Pfeiffer C, Mauro DJ, Lacouture ME. Impact and management of skin toxicity associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy: survey results. Oncology. 2007;72(3–4):152–159. doi: 10.1159/000112795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner LI, Lacouture ME. Dermatologic toxicities associated with EGFR inhibitors: the clinical psychologist’s perspective. Impact on health-related quality of life and implications for clinical management of psychological sequelae. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2007;21(11 Suppl 5):34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, Brown PM, Lynch P, Brown JM, Selby PJ. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(4):714–724. doi: 10.1200/jco.2004.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner LI, Cella D. Dermatologic Principles and Practice in Oncology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013. Psychosocial Issues in Oncology: Clinical Management of Psychosocial Distress, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Special Considerations in Dermatologic Oncology; pp. 60–68. [DOI] [Google Scholar]