Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide. It was reported to account for about 4.7 % of chronic liver disease in Egyptian patients. The present study aimed at studying the different factors that may be implicated in the relationship of schistosomiasis mansoni with HCC in Egypt. A total of 75 Egyptian patients with primary liver tumours (HCC) were enrolled in this study. They were subjected to full history taking and indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA) for the diagnosis of schistosomiasis. According to the results, the patients were categorized into two groups: Group I: 29 patients with negative IHA for schistosomiasis and hepatitis C virus (HCV) positive with no history or laboratory evidence of previous or current Schistosoma mansoni infection. Group II: 46 patients with positive IHA for schistosomiasis and HCV positive. The significant higher proportion of HCC patients in the present study had concomitant HCV and schistosomiasis (61.3 %) compared to HCC patients with HCV alone (38.7 %) suggesting that the co-infection had increased the incidence of HCC among these patients. Analysis of the age distribution among HCC patients revealed that patients in Group II were younger in age at time of diagnosis of HCC with mean age 57.1 years, as compared to patients in Group I with mean age 64.3 years with a highly significant statistical difference between the 2 groups. HCC in Group II was more common in rural residents while it was more common in urban areas in Group I with a significant statistical difference between the 2 groups. Analysis of the sex distribution among the studied groups showed that HCC was more common in males than females in both groups. As regards the aggression of HCC, it was more commonly multifocal and larger in size in patients with concomitant infection than in patients with HCV alone.

Keywords: Schistosoma mansoni, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Risk factors, Egyptian patients

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide, it is the fifth most common malignancy in men and the eighth in women. It accounts for more than 90 % of all primary hepatic tumors (El-Serag 2002).

In Egypt, HCC was reported to account for about 4.7 % of chronic liver disease (CLD) patients (El-Zayadi et al. 2001).

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is considered as a major risk factor for the progression to liver cirrhosis and HCC (Ohata et al. 2004). Integration of the viral DNA into host genome was suggested to be the initiating event for HBV-induced carcinogenesis (Xiong et al. 2003).

The fundamental mechanism by which hepatitis C virus (HCV) is related to HCC is not definitely known. Some studies suggest that HCV mostly plays an indirect role in tumor development and appears to increase the risk of HCC by promoting fibrosis and cirrhosis. On the other hand, other studies suggest that HCV may play a direct role in hepatic carcinogenesis through involvement of viral gene products in inducing liver cell proliferation (El-Nady et al. 2003).

Schistosomiasis is a chronic helminthic disease infecting more than 200 million people worldwide. Concomitant schistosomiasis and HCV infection is common in many developing countries and exhibits a unique clinical, virological, and histological pattern manifested by virus persistence with high HCV RNA titers, higher necroinflammatory and fibrosis scores in liver biopsies, and poor response to interferon therapy. Patients with hepatitis C and Schistosoma mansoni coinfection show markedly accelerated hepatic fibrosis when compared to HCV alone (Kamal et al. 2006).

Literature demonstrates that the association between S. mansoni and HCC is probably an indirect one through potentiating the effect of hepatitis virus. In fact, patients infected by S. mansoni have higher rates of HBV and HCV infection compared with non-infected controls. An experimental study was carried out to clarify whether S. mansoni infection is considered as a risk factor for development of HCC or not, the authors concluded that S. mansoni infection accelerates hepatic dysplastic changes in the presence of other risk factors making cancer appear early and with a more aggressive nature, compared to the same risk in absence of schistosomiasis (El-Tonsy et al. 2013).

El-Zayadi et al. (2005) reported that the epidemiology of HCC in Egypt is characterized by marked demographic and geographic variations.

So, the aim of this work was to study the different factors that may be implicated in the relationship of schistosomiasis mansoni with HCC in Egypt.

Subjects and methods

A total of 75 Egyptian patients with primary liver tumours (HCC) were enrolled in this study. They had been diagnosed by ultrasonography, alpha fetoprotein (AFP) level and fine needle aspiration cytology. All the patients were HCV positive. The patients were residing Cairo, Nile delta and Upper Egypt and were admitted to various cancer institutes in Egypt. No patients had any serological evidence or past history of recent or old hepatitis A, B or D virus infection.

All patients were subjected to the following:

Full history taking (age, residency, history of schistosomiasis or anti-schistosomal treatment, risk factors for HCV transmission like blood transfusion and surgery).

Indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA) (Bilharziose Fumouze Diagnostics/SERFIB, France) for the diagnosis of schistosomiasis. According to the results, the patients were categorized into two groups:

Group I: Twenty-nine patients with negative IHA for schistosomiasis and HCV positive by ELISA and PCR, with no history or laboratory evidence of previous or current S. mansoni infection.

Group II: Forty-six patients with positive IHA for schistosomiasis and HCV positive. These patients gave positive history of schistosomiasis with or without anti-schistosomal therapy.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS statistics (V. 22.0, IBM Corp., USA, 2013) was used for data analysis. Date were expressed as mean ± SD for quantitative parametric measures in addition to Median Percentiles for quantitative non-parametric measures and both number and percentage for categorized data.

The following tests were done:

Comparison between two independent mean groups for parametric data using Student’s t test.

Chi square test to study the association between each 2 variables or comparison between 2 independent groups as regards the categorized data.

The probability of error <0.05 was considered significant, while <0.01 was considered highly significant.

Results

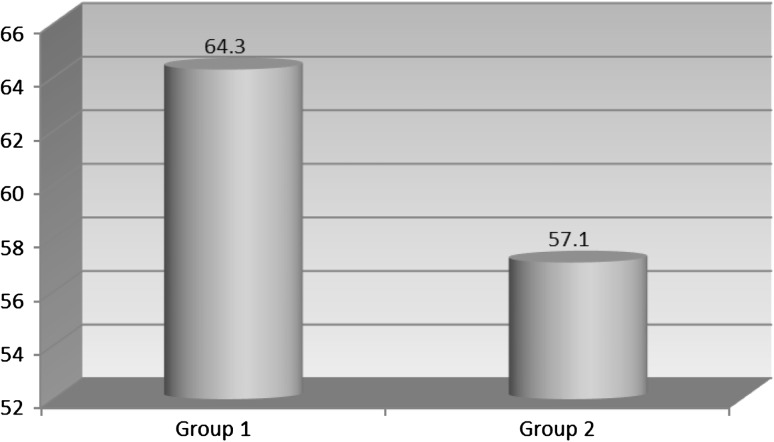

Analysis of the age distribution among HCC patients revealed that patients with co-infection were younger in age at time of diagnosis of HCC; with mean age, 57.1 years, as compared to patients with HCV alone; with mean age, 64.3 years. There was a highly significant difference (P < 0.001) between the two groups (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Age distribution of patients at time of HCC diagnosis

| Mean | SD | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 64.3 | 3.51 | 7.5997 | <0.001 |

| Group II | 57.1 | 4.27 |

P < 0.001 = highly significant statistical difference

Fig. 1.

Mean age of patients at time of HCC diagnosis

In the present study, analysis of the sex distribution among the studied groups of patients showed that there were 19 (65.5 %) male patients in group I and 27 (58.7 %) in group II, while there were 10 (34.5 %) female patients in group I and 19 (41.3 %) in group II. There was no significant statistical difference between the 2 groups since HCC was more common in males than females in both groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sex distribution among studied groups of patients

| Males | Females | χ 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 19 (65.5 %) | 10 (34.5 %) | 0.349 | 0.555 |

| Group II | 27 (58.7 %) | 19 (41.3 %) |

P > 0.05 = no significant statistical difference

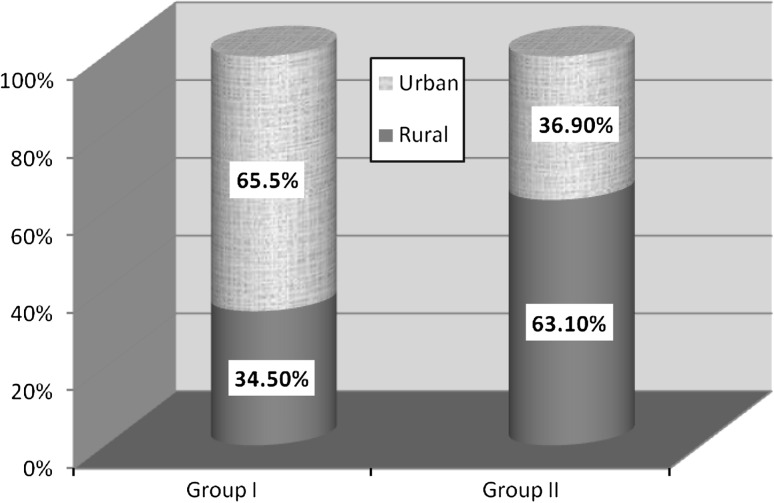

As regards the residential distribution among the studied groups, there was a significant statistical difference (P < 0.05) between groups I and II regarding residential distribution in rural and urban areas with 10 patients (34.5 %) residing in rural areas in group I and 29 patients (63.1 %) in group II, and 19 patients (65.5 %) residing in urban areas in group I and 17 patients (36.9 %) in group II (Table 3; Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Residential distribution among studied groups of patients

| Rural | Urban | χ 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 10 (34.5 %) | 19 (65.5 %) | 5.813 | 0.016 |

| Group II | 29 (63.1 %) | 17 (36.9 %) |

P < 0.05 = significant statistical difference

Fig. 2.

Residential distribution among groups I and II

Comparison between groups I and II as regards the distribution of liver cancer showed that HCC was more commonly multifocal and larger in size in patients with concomitant infection than in patients with HCV alone (Table 4). The table shows that most patients of group II have multifocal lesions distributed in both lobes and most of them have lesions which are >3.0 cm.

Table 4.

Description of liver cancer among the studied groups of patients

| No. of lesions | Site of lesions | Size of lesions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unifocal | Multifocal | Rt. lobe | Lt. lobe | Both | <3.0 cm | >3.0 cm | |

| Group I | 13 | 16 | 14 | 3 | 12 | 15 | 14 |

| Group II | 18 | 28 | 13 | 7 | 26 | 14 | 32 |

Discussion

HCC is the fifth most frequent neoplasm and the third most common cause of cancer related death, accounting for approximately one million deaths per year all over the world (Pleguezuelo et al. 2010).

In the present study, analysis of the age distribution among HCC patients revealed that patients with co-infection were younger in age at time of diagnosis of HCC with mean age 57.1 years, as compared to patients with HCV alone with mean age 64.3 years with a highly significant statistical difference between the 2 groups (Table 1; Fig. 1). The present study also showed that HCC due to co-infection was more common in rural residents as there was a significant statistical difference between the 2 groups as regards residence (Table 3; Fig. 2). This is consistent with the study of El-Zayadi et al. (2005) who found that, the most predominant age group among HCC patients was (40–59 years), with a shift to a younger age group over the last two decades. They attributed that to emergence of HCV infection, as well as to acquisition of both hepatitis B and C virus infection at younger age during schistosomiasis intravenous therapy. Moreover, Abdel-Wahab et al. (2007) found that most of HCC patients were rural residents and farmers. He observed that the mean age of HCC among those patients was 54.26 ± 9.2 with a high prevalence between 51 and 60 years old. Hussein et al. (2004) had also clarified that HCC occurs at younger age group in Upper Egypt as compared to other high risk regions in Asia and attributed that to the involvement of S. mansoni as a risk factor among Egyptian patients.

Analysis of the sex distribution among the studied groups showed that HCC was more common in males than females in both groups. In group I, 65.5 % of patients were males while only 34.5 % were females, and in group II, 58.7 % of patients were males and 41.3 % were females (Table 2). This is consistent with the study of El-Zayadi et al. (2005) where the calculated risk of development of HCC was nearly three times higher in male than in female patients, which may be explained by differences in exposure to risk factors. Yu et al. (1991) mentioned that sex hormones and other X-linked genetic factors may also be important.

As regards the aggression of HCC, it was more commonly multifocal and larger in size in patients with concomitant infection than in patients with HCV alone (Table 4).

In the present study, the significant higher proportion of HCC patients had concomitant HCV and schistosomiasis (61.3 %) compared to HCC patients with HCV alone (38.7 %) suggesting that the co-infection had increased the incidence of HCC among these patients. These results agree with Kamal et al. (2000) who suggested that the combination of chronic schistosomiasis caused by S. mansoni and chronic hepatitis C in Egypt is frequently associated with more rapid progression to cirrhosis and HCC together with higher liver related mortality rates during follow-up. Moreover, Strickland (2006) had shown that in Egypt, 70–90 % of patients with chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis or HCC have co-infection of schistosomiasis and HCV. Also, Angelico et al. (1997) concluded that co-infection of S. mansoni and HCV, are highly prevalent among patients with CLD in Egypt, and this association may have mutual interaction, increasing the severity of liver pathology and the risk of HCC.

Badawi and Michael (1999) had studied the risk factors of HCC in Egypt and concluded that factors associated with increased risk of HCC in Egypt were age over 60 years old, farming, schistosomiasis with relative risk (RR) 95 % and HBV infection with RR 95 %, cigarette smoking and occupational exposure to chemicals. They added that schistosomiasis increased the severity of HBV infection and elevated the risk of HCC in co-infected patients compared to patients with HBV alone.

The high incidence of HCC in patients with schistosomiasis and HCV infection, agrees with similar finding in Japan. Iida et al. (1999) had conducted Japanese preliminary study and found that 19.1 % of patients with CLD and 51 % of HCC cases were co-infected with S. japonicum and HCV. They also conducted a prospective case control study for 10 years which showed that HCC developed in 5.4 % of chronic schistosomiasis cases and in 7.5 % of patients with HCV, with a high incidence of HCV antibodies in patients with chronic schistosomiasis. On the other hand Hassan et al. (2001) in his study of the role of HCV in HCC concluded that HCV infection increases the risk of HCC whereas S. mansoni infection does not. He also conducted the idea that S. mansoni infection may increase the risk of HCC only in the presence of HCV. Recently, Abdel-Rahman et al. (2013) found that positive schistosomal serology is significantly associated with failure of response to HCV treatment despite antischistosomal therapy.

El-Zayadi et al. (2005) through his single center study of the risk factors of HCC in Egypt suggested that schistosomal infection may be a unique invisible risk factor for the development of HCC in Egypt. He attributed that to two factors, either the role of anti-schistosomiasis parenteral therapy in transmission of HCV which is later complicated with HCC, or through persistence of hepatitis B and C viremia due to immune suppression caused by schistosomiasis. However, his results did not reach a statistical significance and he couldn’t identify a direct causal effect of schistosomiasis in development of HCC.

Understanding these relationships may clarify the role of S. mansoni as a risk factor in the development of HCC at an early age which should draw the national attention to provide people at high risk with more effort in the control and prevention of schistosomiasis.

Further investigations must be conducted for the development of a schistosomiasis vaccine that target school children, who are at higher risk for infection and are more vulnerable to the development of HCC due to acquiring infection at young age.

According to the WHO recommendations that all countries should incorporate HBV vaccine into their routine program by 1997, HBV vaccination was discussed to be implemented in the national immunization programs. In the absence of vaccination for hepatitis C, vaccination for schistosomiasis should be also implemented in the national immunization programs in order to decrease the risk of development of HCC among co-infected patients.

Although HCC meets the criteria of a tumor that would benefit from surveillance programs, the poor sensitivity and specificity of currently available tools have hindered their implementation (Pleguezuelo et al. 2010). Currently, only few biomarkers for HCC are available for clinical use, among which only AFP partially fulfills the requirements of an ideal tumor marker (Santamaria et al. 2007). Therefore the application of new technologies to identify a biomarker that can be used as a screening test for HCC in high risk groups must be considered.

It is concluded that schistosomiasis insult on the liver is a slowly progressive one. So it is difficult to initiate alone, within the normal life span of any patient, dysplastic changes that may be a risk factor for HCC development. But it accelerates these dysplastic changes in the presence of any other risk factor making the cancer appear at an earlier age and with a more aggressive nature.

Also, any patients with chronic schistosomal hepatosplenomegaly, especially those who acquired infection in childhood and whose schistosomiasis insult will have the chance to affect their livers a longer period of time, must be followed up for fear of earlier development of HCC.

References

- Abdel-Wahab M, El-Ghawalby N, Mostafa M, Sultan A, El-Sadany M, Fathy O, Salah T, Ezzat F (2007) Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in lower Egypt, Mansoura Gastroenterology Center. Hepatogastroenterology 54(73):157–62 [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman M, El-Sayed M, El Raziky M, Elsharkawy A, El-Akel W, Ghoneim H, Khattab H, Esmat G. Coinfection with hepatitis C virus and schistosomiasis: fibrosis and treatment response. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2013;19(17):2691. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelico M, Renganathan E, Gandin C, Fathy M, Profili MC. Chronic liver disease in the Alexandria governorate, Egypt: contribution of schistosomiasis and hepatitis virus. J Hepatol. 1997;26:236–243. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawi AF, Michael MS. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Egypt: the role of hepatitis-B viral infection and schistosomiasis. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:4565–4569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Nady GM, Ling R, Harrison TJ. Gene expression in HCV associated hepatocellular carcinoma-upregulation of a gene encoding a protein related to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Liver Int. 2003;23:329–337. doi: 10.1034/j.1478-3231.2003.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemiologic view. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35(Suppl. 2):S72–S78. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200211002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Tonsy MM, Hussein HM, Helal TES, Tawfik RA, Koriem KM, Hussein HM. Schistosoma mansoni infection: is it a risk factor for development of hepatocellular carcinoma? Acta Trop. 2013;128(3):542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Zayadi AR, Abaza H, Shawky S, Mohamed MK, Selim OE, Badran HM. Prevalence and epidemiological features of hepatocellular carcinoma in Egypt—a single center experience. Hepatol Res. 2001;19:170–179. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6346(00)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Zayadi AR, Badran HM, Barakat EM, Attia ME, Shawky S, Mohamed MK, Selim O, Saeid A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Egypt: a single center study over a decade. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(33):5193–5198. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i33.5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan MM, Zaghloul AS, El-Serag HB. The role of hepatitis C in HCC: a case control study among Egyptian patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:123–126. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein HM, El-Gindy IM, Abdel-Hamid DM, El-Wakil HS, Maher KM. Characterization of three types of Schistosoma mansoni soluble egg antigen and determination of their immunodiagnostic potential by western blot immunoassay. Egypt J Immunol. 2004;11(1):65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida F, Lida R, Kamijo H, Takaso K, Miyazaki Y, Funabashi W, et al. Chronic Japanese schistosomiasis and hepatocellular carcinoma; ten years of follow-up in Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:573–581. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal S, Madwar M, Bianchi L, Tawil AE, Fawzy R, Peters T, Rasen JW. Clinical, virological and histopathological features: long-term follow-up in patients with chronic hepatitis C co-infected with S. mansoni. Liver. 2000;20:281–289. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020004281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal SM, Turner B, He Q, Rasenack J, Bianchi L, Al Tawil A, Nooman A, Massoud M, Koziel MJ, Afdhal NH. Progression of fibrosis in hepatitis C with and without schistosomiasis: correlation with serum markers of fibrosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:771–779. doi: 10.1002/hep.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohata K, Hamasaki K, Toriyama K, Ishikawa H, Nakao K, Eguchi K. High viral load is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:670–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleguezuelo M, Lopez LM, Rodrigues A, Montero JL, et al. Proteomic analysis for developing new biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2010;2(3):127–135. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i3.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría Enrique, Muñoz Javier, Fernández-Irigoyen Joaquín, Prìeto Jesús, Corrales Fernando J. Toward the discovery of new biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma by proteomics. Liver International. 2007;27(2):163–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland TG. Liver disease in Egypt: hepatitis C superseded schistosomiasis as a result of iatrogenic and biological factors. Perspect Clin Hepatol. 2006;43(5):915–922. doi: 10.1002/hep.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J, Yao YC, Zi XY, Li JX, Wang XM, Ye XT, Zhao SM. Expression of hepatitis B virus X protein in transgenic mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:112–116. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu MC, Tong MJ, Govindarajan S, Henderson BE. Nonviral risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in a low-risk population, the non-Asians of Los Angeles County, California. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1820–1826. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.24.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]