Abstract

Induced defenses are thought to be economical: growth and fitness-limiting resources are only invested into defenses when needed. To date, this putative growth-defense trade-off has not been quantified in a common currency at the level of individual compounds. Here, a quantification method for 15N-labeled proteins enabled a direct comparison of nitrogen (N) allocation to proteins, specifically, ribulose-1,5-bisposphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) as proxy for growth, with that into small N-containing defense metabolites (nicotine, phenolamides) as proxies for defense after herbivory.

After repeated simulated herbivory, total N decreased in the shoots of wild type (WT) Nicotiana attenuata plants, but not in two transgenic lines impaired in jasmonate defense signaling (irLOX3) and phenolamide biosynthesis (irMYB8). N was reallocated among different compounds within elicited rosette leaves: in WT, a strong decrease in total soluble protein (TSP) and RuBisCO was accompanied by an increase in defense metabolites; irLOX3 showed a similar, albeit attenuated pattern; while irMYB8 rosette leaves were the least responsive to elicitation with overall higher levels of RuBisCO. Induced defenses were higher in the older compared to the younger rosette leaves, supporting the hypothesis that tissue developmental stage influences defense investments. We propose that MYB8, probably by regulating the production of phenolamides, indirectly mediates protein pool sizes after herbivory. Although the decrease in absolute N invested in TSP and RuBisCO elicited by simulated herbivory was much larger than the N-requirements of nicotine and phenolamide biosynthesis, 15N flux studies revealed that N for phenolamide synthesis originates from recently assimilated N rather than from RuBisCO turnover.

Keywords: Nicotiana attenuata; caffeoyl-putrescine; dicaffeoyl-spermidine; nicotine; ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase; total soluble protein; IRMS; LC-MSE; R2R3-MYB transcription factor; Manduca sexta

Introduction

Plants have evolved two general direct strategies against herbivory – constitutive and inducible defenses. The biosynthesis of these defenses requires fitness-limiting resources that could otherwise be invested into growth and reproduction. Hence, induced plant defenses are thought to be a cost-saving strategy compared to constitutive defenses, since they are only produced when needed, e.g. after herbivory (Karban and Baldwin 1997) and this cost-saving model plays a central role in most theoretical treatments of induced defenses (see Stamp 2003 for a review of plant defense hypotheses). Several studies have quantified the costs of induction by measuring photosynthesis rates, plant biomass, size and/or yield associated with an increase in defense metabolites (Bazzaz et al. 1987, Karban and Baldwin 1997, Zangerl et al. 2002). While measurements of the impact of anti-herbivore defenses on plant yield are important for understanding their ultimate fitness costs, measurements of plant biomass do not discriminate among the relative investments into compounds that function in growth, storage and defense processes in the analyzed tissues (Chapin et al. 1990). Therefore, the investment into growth is preferably estimated by measuring components of biomass that directly promote the acquisition of resources for growth, such as photosynthetic proteins (Chapin et al. 1990). Additionally, the costs of defense should be measured in the currency of a fitness-limiting resource (Baldwin et al. 1998, Mole 1994). Nitrogen (N) is often such a fitness-limiting resource, determining the growth and reproduction of plants and of the herbivores that eat them. N availability also influences N allocation to defense metabolites (Baldwin et al. 1998, Lou and Baldwin 2004, Simon et al. 2010). Thus, it is an ideal currency to use for the study of growth-defense trade-offs in plant-herbivore interactions.

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO), is the most abundant foliar protein in plants and is essential for the dark reaction of photosynthesis. RuBisCO constitutes 30-50% of the total soluble protein (TSP) in C3 plants (Ellis 1979, Imai et al.2008, Makino et al. 1984), and may function as a potential N storage protein (Millard 1988), consequently it represents a major N sink in plants. Its large and small subunit (LSU and SSU, respectively) are synthesized from separate precursor pools which have different metabolic origins (Allen et al. 2012). Although the amount and activity of RuBisCO are not the only factors controlling growth (Stitt and Schulze 1994), changes in RuBisCO expression influence growth and lead to complex changes in N metabolism (Matt et al. 2002, Stitt and Krapp 1999, Stitt and Schulze 1994), making this enzyme a reasonable proxy for growth parameters.

Nicotiana attenuata is a wild tobacco native to the Great Basin Desert in south-western USA that synchronizes its germination from long-lived seed banks in response to exposure to cues from pyrolized vegetation (Preston and Baldwin 1999). By timing its germination with the immediate post-fire environment, N. attenuata takes advantage of the abundant, yet ephemeral, pools of inorganic N in burned soil (Lynds and Baldwin 1998), but is subject to high intra-specific competition for this fitness-limiting resource, due to its mass germination behavior. Furthermore, since it is a pioneer species, N. attenuata is attacked by a diverse herbivore community, including the specialist tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta). Herbivore attack elicits the jasmonic acid (JA) signaling cascade (Kessler et al. 2004), which activates JA-responsive transcription factors that lead to the biosynthesis of a plethora of induced small metabolites (Figure 1a, Woldemariam et al. 2011), such as the N-intensive alkaloid nicotine, and a variety of phenolamides, which decrease herbivore performance (Baldwin 1999, Kaur et al. 2010, Onkokesung et al. 2010, Steppuhn et al. 2004). The biosynthesis of nicotine and phenolamides requires the same amino acid precursors (ornithine and arginine for putrescine and spermidine biosynthesis, Kaur et al. 2010, Steppuhn et al. 2004, Takano et al. 2012), but nicotine is produced only in the roots (Hibi et al. 1994), while phenolamides are synthesized in the attacked leaf (Kaur et al. 2010).

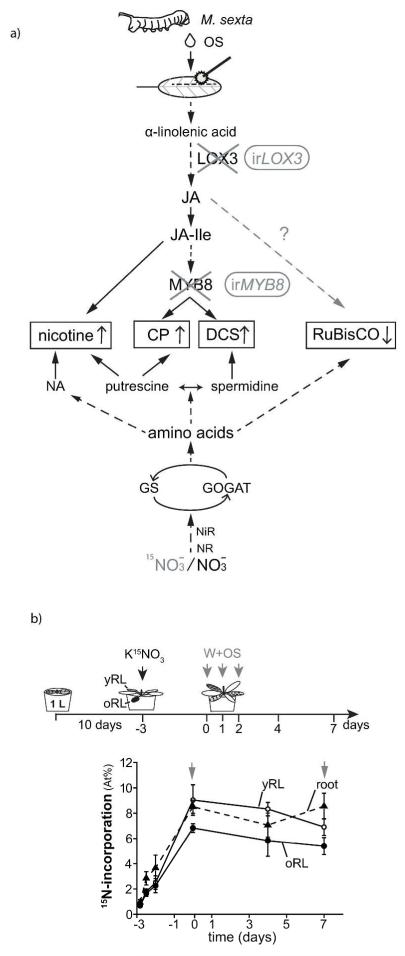

Figure 1.

Overview of experimental strategy used to study growth-defense trade-offs in Nicotiana attenuata in a common nitrogen (N) currency.

a) The biosynthesis of nicotine, caffeoyl-putrescine (CP) and dicaffeoyl-spermidine (DCS) is induced after simulated herbivory in wild type (WT) by wounding (W) with a pattern wheel and application of oral secretions (OS) of Manduca sexta, but is impaired in the transgenic plants silenced in the expression of lipoxygenase 3 (LOX3) or MYB8 by RNAi with inverted-repeat (ir) constructs. The concentration of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) decreases in WT after W+OS, but the effects of jasmonic acid (JA) on N-investment into RuBisCO are unclear. Amino acids serve as precursors for putrescine and spermidine and for nicotinic acid (NA), which provide N for the synthesis of these metabolites. Amino acids are derived from nitrate (NO3−) reduction, followed by assimilation catalyzed by glutamine synthetase (GS) and glutamate synthase (GOGAT), and are also used as precursors for RuBisCO synthesis. JA-Ile=JA- isoleucine; NR=nitrate reductase; NiR=nitrite reductase.

b) 15N-incorporation into roots, younger (yRL) and older rosette leaves (oRL) following pulse-labeling with K15NO3 27 days after germination was determined by isotope-ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) (n=5). Grey arrows indicate the time-points of elicitation in the following experiments. During this time-frame 15N-incorporation was stable. At%=atomic percent.

Nicotine is present constitutively in undamaged N. attenuata tissues and foliar concentrations increase substantially after herbivory (Baldwin 1999, McCloud and Baldwin 1997). The two major phenolamides found in N. attenuata are the N-acylated polyamines caffeoyl-putrescine (CP) and dicaffeoyl-spermidine (DCS), whose biosynthesis is regulated by the transcription factor NaMYB8 (hereafter MYB8, Figure 1a). Both CP and DCS accumulate constitutively in reproductive tissues and are strongly induced in leaves by simulated herbivory (Kaur et al. 2010). Herbivory also causes large scale changes in N. attenuata’s transcriptome and proteome, decreasing levels of photosynthetic genes and proteins, including RuBisCO (Giri et al. 2006, Halitschke et al. 2003, Voelckel and Baldwin 2004b). Due to the important constraints imposed by N availability upon both its growth and defense, as well as the wealth of understanding of its anti-herbivore defenses and the availability of isogenic transgenic lines impaired in individual classes of defenses, N. attenuata is an ideal model in which to study growth-defense trade-offs in a common N currency.

Induction of defense responses in wild tobacco can be simulated in a standardized and synchronized way by wounding leaves and applying oral secretions (OS) of M. sexta larvae to the wounds (W+OS, Fig. 1). The major elicitors in M. sexta OS are fatty acid amino acid conjugates (FAC) which are recognized by the plant, triggering defense responses (Giri et al. 2006, Halitschke et al. 2003, Schittko et al. 2001). The FAC composition of OS and resulting gene expression and metabolite induction in the plant differ between specialist and generalist folivores (Diezel et al. 2009, Steinbrenner et al. 2011, Voelckel and Baldwin 2004a).

Here, we quantified the N-investments into different plant parts and among different N pools within a tissue to compare the investments into growth and defense in the same currency after repeated simulated herbivory by W+OS-elicitation of a specialist herbivore. Repeated simulated herbivory, in contrast to single W+OS elicitation, more closely mimics natural herbivore feeding, which varies in duration and timing (Van Dam et al. 2001, Skibbe et al. 2008, Stork et al.2009). A stable isotope labeling technique was used to track N flux among different pools of individual compounds in locally-elicited and systemic leaves and seeds. We applied 15N labeled nitrate to the soil because nitrate is the most common form of N taken up by N. attenuata in nature, after rapid biological nitrification of the ammonium generated by pyrolysis (Figure 1, Lynds and Baldwin 1998).

The N-flux into the three major N-intensive small metabolites of N. attenuata (nicotine, CP and DCS) was used as proxy for defense investment that could be directly compared to the N-investment into proteins, and in particular the abundant photosynthetic protein, RuBisCO, as a proxy for growth-related investment. These different molecule classes could not be measured in the past with comparable precision and accuracy due to a lack of suitable methods especially for proteins. Here, we used a high-throughput LC-MSE method for the absolute quantitation of proteins and 15N-incorporation into peptides (Ullmann-Zeunert et al. 2012) which allows for the quantification of single large proteins with the same accuracy as small defense metabolites quantified by UPLC/UV/ToF-MS.

To further disentangle the effects of induced defenses on N allocation after herbivory, we compared two previously described transgenic lines, one deficient in JA signaling, irLOX3 (Allmann et al. 2010), and one deficient in the biosynthesis of phenolamides, irMYB8 (Kaur et al. 2010), with wild type (WT) plants (Fig. 1a). This design allows for a direct comparison of N-flux into specific classes of defense compounds with that into growth-related proteins measured in the same N currency, and an evaluation of the hypothesis that RuBisCO is used as N-storage compound for defense responses.

Results and Discussion

Anti-herbivore defense elicitation alters shoot N contents

Herbivory is known to change resource allocation within plants (Bazzaz et al. 1987, Frost and Hunter 2008, Gomez et al. 2010). To estimate the impact of the biosynthesis of N-containing defense metabolites on N accumulation in N. attenuata, we compared the shoot N contents (% dry mass) of the two transgenic lines impaired in defense responses with WT plants after repeated simulated herbivory with W+OS. The isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) measurements revealed that repeated elicitation reduced the N content of WT shoots (total of N per dry mass of, Welch two sample T-test, df=7.24, p=0.032), but not of the transgenic lines (Fig. 2), while the N pool sizes were slightly reduced after elicitation for all three genotypes (Fig. S1b). Changes in the N pool sizes of elicited irLOX3 and irMYB8 plants were due to a reduction in shoot dry mass (Fig. S1), while elicited WT showed both reduced shoot dry mass and reduced shoot N content, suggesting a possible N reallocation within the plant caused by the biosynthesis of N-containing defense metabolites.

Figure 2.

Total N content in WT shoots decreases after simulated herbivory.

N content of shoots of irLOX3, irMYB8 and WT (n=5) was determined by IRMS 4 days after the first W+OS elicitation. Unelicited plants were controls. Asterisks represent significant differences between treatments (*: p ≤ 0.05; n=5). Inset: The N content of WT roots (n = 5) was determined in a separate experiment at the same time-point. DM=dry mass

Plants can allocate N to roots to protect this resource from folivores and to reduce the nutritional value of the attacked tissues, which, together with increased defenses, can slow herbivore growth and increase their exposure to natural enemies (Trumble et al. 1993). Previous studies with tomato demonstrated that N allocation in the form of amino acids from the shoot to the roots was rapidly induced by methyl-jasmonate (MeJA) (Gomez et al. 2010) and M. sexta feeding (Gomez et al. 2012, Steinbrenner et al. 2011). In N. attenuata, OS-elicitation has been shown to cause a rapid allocation of carbon from the shoot to the roots, which can later be used for regrowth and reflowering (Schwachtje et al. 2006). The reduced N concentration of WT shoots in our experiment suggests that this species can also allocate N from the shoot to the roots after herbivory. This inference is consistent with the observation that N contents of WT roots increased after elicitation, as measured in a separate experiment, though the increase was not quite significant (Welch two sample t-test, df=4.71, p=0.054; inset Fig. 2). Alternatively, the increased N content of roots may have resulted from increased N assimilation, but previous 15N labeling experiments in this species have found no evidence for changes in N assimilation rate after herbivory (Baldwin and Ohnmeiss 1994, Lynds and Baldwin 1998). Therefore, we conclude that the induced biosynthesis of N-containing metabolites after OS-elicitation alters whole-plant N partitioning.

Changes in absolute pool sizes depend on developmental stage

To analyze the influence of anti-herbivore defense induction, especially phenolamide biosynthesis, on within-shoot N allocation, we determined the absolute N pools of different leaf types (hereafter, total N pools) and N allocation to seeds by IRMS. Expressing resource allocation as concentrations reveals proportional allocations within an organ; however, total pools allow for comparisons among organs, since they are a function of both organ size and concentration (Chapin et al. 1990). We analyzed elicited older (oRL) and younger (yRL) rosette leaves to explore the influence of leaf development on N reallocation after elicitation, and the first (unelicited) stem leaf (S1) to examine systemic effects.

Overall, there was no clear effect of genotype or elicitation on the leaf total N pools. Total N pools varied among genotypes only in the S1 leaf (ANOVA, F1,27=4.86, p=0.036), while OS-elicitation only reduced the total N pool of irLOX3 (two sample t-test, df=8, p=0.006) and WT (two sample t test, df=8, p=0.021) in the yRL (ANOVA, F1,28=7.40, p=0.011). The N pool size in oRL was unaffected by genotype and elicitation (Fig. 3). As N pool size correlates with biomass at the whole-plant scale (Baldwin and Hamilton 2000), we evaluated if the observed changes in total N pools of single leaves could be explained by changes in growth. Although the leaf size of yRL was reduced after elicitation (ANOVA, F1,24=12.33, p=0.002) (Fig. S2a), it did not correlate with total N pools (ANCOVA, p = 0.187). Similarly, the change in total N pools of S1 leaves was not correlated with changes in leaf size (ANCOVA, p=0.406).

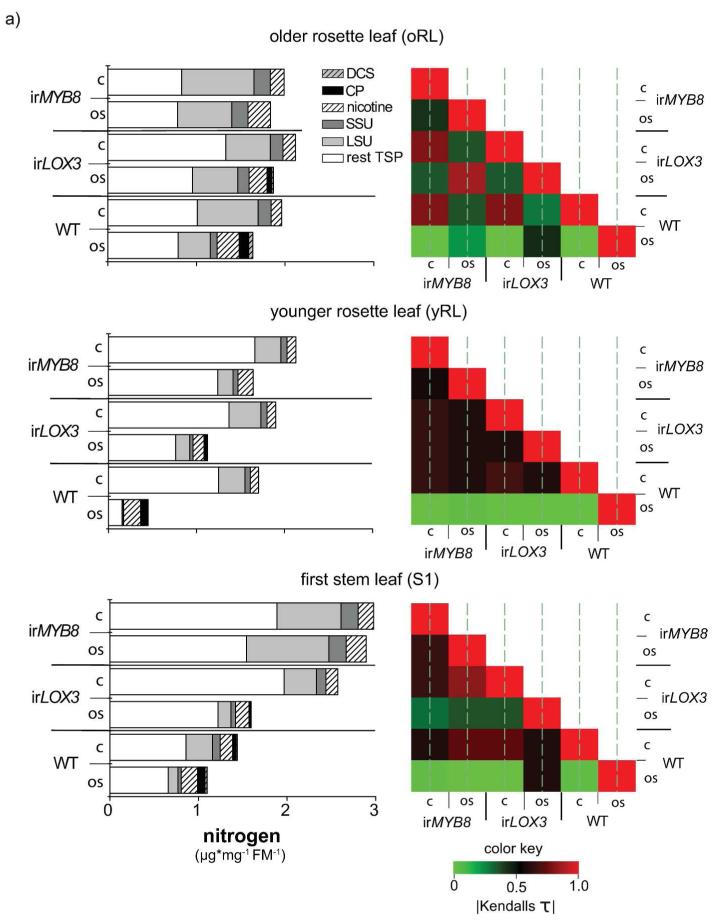

Figure 3.

Silencing of LOX3 and MYB8 alters the N distribution between and within leaves.

The N pools and total soluble protein (TSP) of leaves (oRL, yRL, S1=1st stem leaf) of irLOX3, irMYB8 and WT, calculated based on leaf mass. The N content was determined by IRMS and the TSP was measured by the Bradford assay. Plants were elicited as described for Figure 2. yRL and oRL were harvested 4 days after the first W+OS elicitation and when S1 leaves underwent the source-sink transition. Asterisks indicate differences among treatments (*: p ≤ 0.05; **: p ≤ 0.01; ***: p ≤ 0.001). Letters represent significant differences found using the minimum adequate model (n=5). For abbreviations see Figure 1.

It is possible that changes in the total N pool of a leaf reflect changes in a major pool within the leaf, such as proteins. Although TSP pool size dramatically decreased in the yRL after elicitation, it did not correlate with the total N pool size in this tissue (ANCOVA, p=0.122; Fig. 3). Thus, we conclude that although both pools are reduced by elicitation, the total N pool of the rosette leaves does not reflect the changes in TSP pool size or leaf size. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that total leaf N content and TSP (RuBisCO content) are controlled by different mechanisms, as has been shown for rice (Ishimaru et al. 2001, Makino et al. 2000).

TSP pools differed between the lines in all three leaf types (ANOVA, oRL: F1,27=8.70, p=0.007; yRL: F1,27=12.95, p=0.001; S1: F1,27=44.77, p=3.5*10−07; Fig. 3). The TSP pools of irLOX3 and irMYB8 in the yRL were reduced by about 50% after OS-elicitation, while WT TSP pools were reduced by 91%. Both transgenic lines had constitutively larger TSP pools in the S1 leaf than did WT and although S1 TSP decreased after elicitation in irLOX3 plants, TSP pools of both transgenic lines were still 2.5 to 3 times larger than those of WT after elicitation (Fig. 3), suggesting that the biosynthesis of N-containing metabolites affects protein pool sizes, and that inducible defenses also have constitutive costs.

The recently developed method for the absolute quantification of single proteins allowed us to quantitatively compare the investment in defense metabolites with that in growth-related compounds, specifically, the photosynthetic protein RuBisCO, with similar accuracy (Ullmann-Zeunert et al. 2012). Being the most abundant soluble protein in plants, the total amount of RuBisCO (sum of LSU and SSU) reflected the TSP pattern in the different leaves independent of genotypes (ANCOVA, oRL: p<0.0001; yRL: p<0.0001; S1: p=0.42; Fig. 3, Fig.S3a). Overall, the data revealed a decrease in pool sizes of both RuBisCO subunits after OS-elicitation (Fig. S3a), which coincided with an increase in N-containing defense metabolites (Fig. S3b), but the effects differed among lines, and for most traits measured, irLOX3 showed an intermediate phenotype between WT and irMYB8. The two transgenic lines with either reduced (irLOX3) or undetectable levels of CP and DCS (irMYB8; Fig. S3b) showed a smaller decrease of RuBisCO LSU and SSU than did WT in the elicited yRL (47-59% in irMYB8/irLOX3 compared to 92 95% in WT; Fig. S3a). RuBisCO LSU and SSU levels were unaltered after elicitation in the systemic S1 leaf of irMYB8, but strongly declined in WT and irLOX3. The nicotine pool sizes showed similar induction patterns for all lines, except in the yRL, where the OS-elicited nicotine levels were higher in WT than in the transgenic lines. These data suggest that the growth-defense trade-offs at the leaf scale are probably influenced by the capacity to biosynthesize and accumulate phenolamides, and that this also affects growth investments in the systemic S1 leaf.

Since all transgenic lines used in this study accumulated similar amounts of nicotine, it is unclear whether the biosynthesis of this alkaloid might affect N allocation to proteins (Fig. S3b). To answer this question rigorously, experiments with transgenic lines completely silenced in the flux of N into nicotine biosynthesis are needed. In the nicotine-silenced transgenic lines we have produced in our laboratory by silencing putrescine N-methyl transferase, nicotine biosynthesis is silenced, but the elicited flux of N into other alkaloids (anatabine) is not (Steppuhn et al. 2004).

Similarly, the induction of proteinase inhibitors could have additional influence on N-allocation. However, preliminary experiments with virus-induced empty vector and MYB8-silenced plants showed a similar trypsin proteinase activity in both plants after elicitation (H. Kaur, personal communication), indicating that the synthesis of proteinase inhibitors seems not to play a key role in the reallocation of N from primary to secondary metabolism.

A comparison of the two locally elicited leaves revealed differences in their defense and growth pool sizes: while the oRL accumulated the largest defense metabolite pools with only slight reductions in TSP and both RuBisCO subunits after elicitation, the yRL had the strongest reductions in protein pools, with less pronounced increases in N-containing defense metabolite levels than the oRL (Fig. 3, Fig. S3). The optimal defense theory predicts that the allocation of defense metabolites is directly proportional to the fitness value of different plant parts (McKey 1974, McKey 1979, Rhoades 1979) and many studies have demonstrated that younger leaves of N. attenuata, presumed to have a higher fitness value than older leaves, contain higher defense metabolite levels (Zavala et al. 2004a, Kaur et al. 2010, Onkokesung et al. 2012). These results appear to contradict our findings, because the oRL contained higher metabolite levels than did the yRL, however, the previous studies compared concentrations of metabolites in elicited rosette leaves at different stages of plant development, while here we analyzed metabolite pool sizes of two elicited rosette leaves, of different maturity, harvested simultaneously from the same plant. Since the plants were just beginning stalk elongation at the time of OS-elicitation, both oRL and yRL are likely to be important tissues for later plant growth and reproduction. Thus the larger defense metabolite pools of the mature oRL- which was a source leaf at the time-point of the first elicitation -may be due to its larger nutrient pools, which are probably important for regrowth capacity. Meanwhile, the smaller pools of TSP and RuBisCO in elicited yRL- which was in the transition stage from sink to source during the first W+OS treatment - may reflect a lower N allocation to proteins in developing leaves, which could enhance their defense status by reducing the food quality for herbivores. This is in agreement with the model from Orians et al. (2011), assuming that the mature source leaf allocates resources not only to defense and growth but also to storage, thus making it relatively more valuable for the whole plant, and therefore better protected. Regardless of their ultimate explanations, these data demonstrate that growth-defense trade-offs are dependent on leaf development.

Many previous studies have demonstrated that inducible defenses are costly, often leading to a decrease in reproductive performance (Heil and Baldwin 2002); e.g. growth-defense trade-offs at the leaf scale affect the N allocation to capsules in N. sylvestris (Ohnmeiss and Baldwin 2000). However, here, neither the time of flowering and seed ripening, nor the number of mature capsules, the mass of the first mature seed capsule, nor the total N content of the first seed capsule were significantly different from controls after repeated simulated herbivory (Fig. S4). This lack of observed fitness effects could be due to species-specific differences or differences in the experimental design. In our experiment, OS-elicitation may have been too early to affect seed set (first capsules were harvested on average 18 days after the last elicitation) or the W+OS treatment was too weak to elicit changes in allocation to seeds, compared to the relatively stronger MeJA elicitation used in other experiments (Voelckel et al. 2001). In nature, wild tobacco faces strong intraspecific competition due to its mass-germination behavior, and strong alterations in N allocation to reproductive units in greenhouse cultivated tobacco were only found when MeJA-elicited plants competed with control plants for the same limited resources (Van Dam and Baldwin 2001, Baldwin 1998). Thus, the costs and benefits of N allocation for a plant after herbivore attack may only become obvious, if neighboring plants competing for the same limited resources are present. Additional experiments with plants grown in competition and exposed to simulated and natural herbivory are necessary to further explore the impact of growth-defense trade-offs within the leaf on plant fitness.

MYB8 indirectly affects N-investments into proteins

The pool sizes of proteins and defense metabolites of the two transgenic lines suggest an influence of N-containing metabolite biosynthesis on the observed growth-defense trade-offs, but did not allow for a direct comparison of the amounts of N demanded for metabolite biosynthesis and the decreased N partitioned into TSP and RuBisCO after herbivory. By calculating the N-investment into growth and defense per mg of fresh tissue mass after elicitation, we were able to further explore the role of phenolamide biosynthesis on N reallocation. We combined this approach with 15N pulse labeling to follow the investment of a defined N pool into both plant functions.

For all lines and in both locally treated leaves, elicitation decreased N-investment into rest TSP and RuBisCO per mg fresh mass compared to controls. Particularly in yRLs, the decrease in N-investment into TSP (rest TSP and RuBisCO) was much more pronounced in WT (89%) compared to 28% in irMYB8 and 47% in irLOX3 (Fig. 4a). IrLOX3 plants, for all parameters measured here, showed similar, but less pronounced N-allocation patterns after elicitation as WT. These patterns are consistent with the correlation analysis of all measured N pools (Fig 4a, heatmaps). Correlating all genotype/treatment groups with each other revealed that OS-elicited WT plants did not correlate with the other genotype/treatment groups in all three leaf types. Only OS-elicited irLOX3oRL and S1 leaves showed a weak correlation to WT-OS. In contrast, irMYB8-OS did not correlate with any other genotype by treatment group.

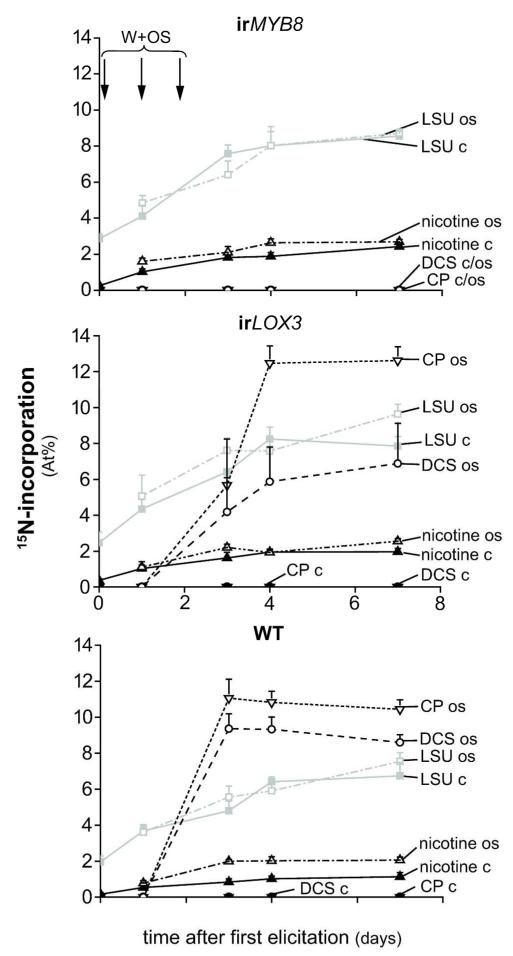

Figure 4.

Increased N-investment in nicotine, CP and DCS is accompanied by a decreased N-investment in protein.

a) N-investment in residual TSP (TSP - (SSU + LSU)), RubisCO large (LSU) and small (SSU) subunit, nicotine, CP and DCS in oRL, yRL and S1 was calculated by multiplying the proportion of N in each compound with the concentration of the compound for each leaf. The amount of TSP was quantified by the Bradford assay, RuBisCO LSU and SSU were determined by LC-MSE and the defense metabolites by UPLC-UV-ToF-MS. Plants were elicited as described for Figure 2 and leaves were harvested as described for Figure 3 (n=5). FM=fresh mass. For other abbreviations see Figure 1.

Heatmaps represent Kendall’s τ coefficient for pairwise correlation of N-investment in all of the above compounds among all genotype/elicitation groups.

b) 15N-investment in RuBisCO LSU and SSU and defense metabolites was calculated as 15N-incorporation multiplied by the N-investment. Plants were pulse-labeled with K15NO3 3 days before the first treatment. 15N-incorporation was determined based on the MS-spectra with ProSipQuant (Taubert et al. 2011).

Interestingly, the observed N-investment pattern is congruent with previous results on the patterns of MYB8 transcript accumulation in N. attenuata asLOX3 plants (which are comparable to irLOX3,Allmann et al. 2010, Halitschke et al. 2004). After elicitation, asLOX3 leaves have 4 times lower MYB8 transcript levels, while irMYB8 have 10 times lower levels than WT leaves (Onkokesung et al. 2012, Kaur et al. 2010). Furthermore, MYB8 functions downstream of JA signaling, and OS-elicited JA levels are not altered in irMYB8 plants (Kaur et al. 2010), whereas they are significantly reduced in LOX3-silenced lines (to about one third of WT, but roughly 6 to 7 times higher than in untreated controls, Allmann et al. 2010). Thus, the observed phenotypes of the two transgenic lines are consistent with their respective MYB8 transcript levels, but not their JA levels; the MYB8 expression after elicitation in the three lines used in this study is inversely proportional to the N-investments into soluble proteins. Based on these results we conclude that the observed changes in N allocation after simulated herbivory only indirectly depend on JA signaling, and are probably caused by differences in MYB8 expression or the MYB8-regulated synthesis of phenolamides. MYB8 could regulate defense induction by playing a role in N assimilation and allocation. In other plants and algae, members of the R2R3-MYB transcription factor family, to which NaMYB8 belongs, have been shown to be crucial for increases in the abundance of transcripts of N assimilation genes (Imamura et al. 2009, Miyake et al. 2003). To further elucidate the putative role of MYB8 in N reallocation, more detailed expression and enzyme activity studies targeting N metabolism at later time-points after herbivory are necessary.

Based on our data we cannot differentiate if MYB8 itself or the synthesis of phenolamides, in particular CP and DCS, mediate the changes in N-investment into growth and defense. Silencing MYB8 also silences genes further downstream of the transcription factor, and in addition to CP and DCS, the synthesis of at least 29 different coumaroyl-, caffeoyl- and feruloyl containing metabolites (Onkokesung et al. 2012). It is difficult to pinpoint the effects of single compounds in the complex biosynthetic network of a leaf, but applying phenolamides in different amounts to control and elicited leaves of irMYB8 plants, and evaluating their effects on protein (RuBisCO) levels, or using plants silenced in genes affecting phenolamide biosynthesis downstream of MYB8 can help to evaluate if either MYB8 alone or MYB8 indirectly through phenolamide biosynthesis mediates the changes in N-investment into proteins.

A comparison of the total N-investment with the 15N-investment per mg fresh mass revealed a similar pattern, with increased 15N in defense compounds and decreased 15N in both RuBisCO subunits after elicitation. One major difference was that WT and irLOX3 plants allocated proportionally more 15N than total N into CP and DCS, and less into nicotine, after elicitation, while the 15N-investment into the RuBisCO subunits was proportionally similar to the total N-investment in both control and elicited leaves (Fig. 4b; for a clearer comparison of N- and 15N-investment see Fig. S5). Larger investments of recently assimilated 15N into CP and DCS compared to nicotine makes ecological sense, because the OS used was from M. sexta larvae, a tobacco specialist, which is nicotine-tolerant but negatively affected by phenolamides (Kaur et al. 2010).

A comparison of the decrease in total N-investment into RuBiSCO and TSP after OS-elicitation with the N-requirements of nicotine and phenolamide biosynthesis (Fig. 4a, Fig. S6 showing a time-course analysis) suggested that RuBisCO metabolism could be a source of reallocated N to defense metabolite biosynthesis. Based on concentrations in the yRL, about 54% of N from RuBisCO or 13% of N from TSP could have been invested into phenolamides and nicotine (Fig. S5).This comparison does not take into account the N-requirements of biosynthetic enzymes or other N-containing inducible defense compounds such as proteinase inhibitors (Zavala et al. 2004b). Hence, the N demands for defense metabolite biosynthesis are likely underestimated; however, considering the dramatic decline in TSP it is likely that more N is released from the turnover of primary metabolism than N invested into defense metabolites.

N invested into phenolamides does not originate from RuBisCO after herbivory

To further elucidate the N-flux into defense metabolites and to investigate if RuBisCO N is used as a source of N for CP and DCS biosynthesis after OS-elicitation, the 15N-incorporation (atomic percent, At%) into N-containing metabolites and RuBisCO was determined in a time-course experiment (see Fig. 1b for details). This approach allows one to follow the N-flux of a known amount of 15N, independently of within-leaf N pool sizes. The experiment was carried out with the yRL, because this leaf showed the greatest differences in N-investment after elicitation (Fig. 4a,b). It is important to note that during the experimental period, the 15N-incorporation of the whole leaf was constant in all three lines, independent of elicitation (Fig. S7), indicating that N is mainly redistributed within the leaves and that there is no increased net N-influx into the leaf after elicitation.

As the 15N-incorporation into RuBisCO LSU and SSU was similar, we only report the incorporation into LSU. Incorporation into RuBisCO increased at a constant rate until it reached a maximum of about 8 At% between 4 and 7 days after the 1st OS-elicitation in all three lines, independent of elicitation (Fig. 5). In contrast, 15N was rapidly incorporated into CP and DCS in OS-elicited leaves until these compounds attained a maximum of about 10-12 At%, 4 days after the 1st elicitation in WT and irLOX3 plants. Had RuBisCO degradation provided the precursors for PA biosynthesis, it should have a similar or higher 15N-incorporation as did both phenolamides, since precursor pools will have similar or higher labeled isotope incorporation rates as their derived compounds. The large differences in 15N-incorporation between CP and DCS and LSU make it unlikely that N derived from RuBisCO was used for CP and DCS biosynthesis. This result challenges the common conception that N released from products of primary metabolism (proteins) is a direct source for the production of defense metabolites (Herms and Mattson 1992, Schwachtje et al. 2006). In contrast, the data indicate that recently assimilated N is channeled into defense metabolite synthesis (Fig. 4b). We hypothesize that N released from TSP turnover is mainly reinvested into other compounds, enabling the plant to react in different ways upon attack. Thus, plants may reduce the nutritive value of the tissue by reducing the amount of TSP and at the same time investing N not only in defense metabolites, but also in other N-containing compounds which are less digestible for the herbivore or more easily reallocated.

Figure 5.

Dynamics of 15N-incorporation into nicotine, CP, DCS and LSU demonstrates that recently assimilated N, not N derived from LSU metabolism, is rapidly invested into CP and DCS biosynthesis after elicitation.

Three days before the first W+OS treatment plants were pulse labeled with K15NO3 (see Fig. 1a). The yRL at the time of labeling was harvested at indicated time points. 15N-incorporation (n=5) of RuBisCO LSU, nicotine, CP and DCS was determined as described for Figure 4. For abbreviations see Figure 1.

15N-incorporation into nicotine only increased slightly after elicitation and reached a maximum of around 2 At% in all three lines (Fig. 5), though roots had a labeling of about 8 At%, similar to leaves (Fig. S6). These findings differ from previous results showing the rapid incorporation of recently assimilated 15N into nicotine after elicitation, but those results were obtained from plants that were N-starved for 24h before application of the 15N pulse, and 15N was applied at the same time as MeJA to the roots (Baldwin et al. 1994, Lynds and Baldwin 1998). Elicitation of roots and shoots is known to differentially affect the accumulation of defense metabolites (van Dam and Oomen 2008). Furthermore, MeJA is a stronger elicitor than OS elicitation (Voelckel et al. 2001), and N-starved plants are known to transport N preferentially to the strongest sink (Ohtake et al. 2001).These differences in experimental design probably led to different source-sink relationships within the plant, resulting in different patterns of 15N-investments.

Nicotine is a constitutively synthesized pool in the roots in N. attenuata, which is transported to the shoot, but not metabolized, and contains 5-8 % of the plant’s total N (Baldwin and Hamilton 2000). It is possible that the newly synthesized nicotine might be diluted by the large pool of previously synthesized unlabeled nicotine, resulting in a low 15N-incorporation. Alternatively, it may be derived from previously synthesized (and therefore unlabeled) precursors.

In summary, the 15N-incoporation illustrates the flux of a defined 15N pulse, independent of pool size, and indicates that N invested into CP and DCS is unlikely derived from RuBisCO, but is allocated directly to defense processes after assimilation instead of growth processes.

Conclusion

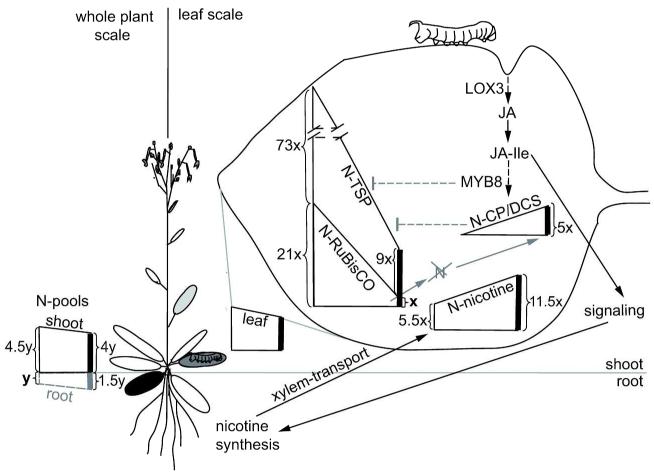

In this study, we quantified simulated herbivory-induced growth-defense trade-offs in a unified currency by measuring the investments of the limited resource N into RuBisCO as proxy for growth and into small defense related compounds (nicotine, phenolamides). In N. attenuata, OS-elicitation reconfigures N allocation at multiple scales. Figure 6 summarizes the relative changes in the different N-pool sizes after repeated simulated herbivory in the yRL. At the whole-plant scale, OS-elicitation induced a weak N re-allocation from the shoot to the root, thus, presumably giving attacked plants a higher tolerance against herbivores by reducing the chances that valuable resources are removed by herbivores and by increasing regrowth capacity after attack. At the within-leaf scale, changes between different N pools are much more dramatic. Taking the N-amount of RuBisCO after elicitation as a reference (x), RuBisCO-N declined 21×, and TSP from 73 to 9×, while N-investment into defense metabolites increased, but to a far lesser extent (increase from 5.5× to 11.5× for nicotine and 5× for CP and DCS).

Figure 6.

Herbivory-induced trade-offs of N-investment into growth and defense are mediated by MYB8.

N-investment in defense causes a reallocation of N from the shoot to the root. We suggest that the transcription factor MYB8 probably via the synthesis of phenolamides (CP, DCS) is involved in the reallocation of N within the local leaf. N invested in phenolamides and in the root synthesized alkaloid nicotine increases after herbivory, while the N-investment in TSP and RuBisCO strongly decreases, but it is unlikely that N invested into phenolamides originates from RuBisCO metabolism. The height of the left and right side of the quadrangles represent relative changes in N-pool sizes for each compound of C and OS-elicited plants, respectively, using the N-amount of RuBisCO after elicitation as a reference (x). All N-pools within the depicted leaf show the ratios of measured values per mg fresh mass. Shoot, root and whole-leaf N-pools depicted outside the plant represent ratios of N determined per mg dry mass. For abbreviations see Figure 1.

The transcription factor NaMYB8, possibly by regulating the production of metabolically dynamic phenolamides, CP and DCS, indirectly mediates the reconfiguration of N-allocation after elicitation. The comparison of two elicited rosette leaves indicated that the extent of reconfiguration and the total amount of defense metabolites produced depends on the developmental stage of the leaf, and on source-sink relationships.

15N flux studies strongly indicated that the N for PA biosynthesis comes from recently assimilated N rather than RuBisCO turnover. These results suggest that the drastic reallocation of resources and the shut-down of investments into growth within the leaf are not primarily driven by the direct costs for defense metabolite biosynthesis but rather that N release from primary metabolism may enable the plants to react in multiple ways to attack. It remains to be elucidated if and how these allocation costs are translated into ecological costs. This question can only be answered if plants are grown in competition under different levels of herbivore attack.

Future experiments will seek to validate these results under more natural settings by comparing the results shown here for simulated herbivory using OS of a specialist folivore to damage by the natural herbivore community. An additional focus will be on tracing N-investments into further metabolites and non-soluble proteins, and following the N-flux at whole plant level in more detail.

Experimental Procedures

Plant germination and growth conditions

Seeds of the 31st generation of an inbred WT line of Nicotiana attenuata Torr. ex. Watts (Solanaceae) and two stably transformed lines, irMYB8 with reduced expression of the transcription factor NaMYB8 (A-08-810, Kaur et al. 2010), and irLOX3 silenced in lipoxygenase 3 (NaLOX3, A-03-562-2, Allmann et al. 2010), were sterilized and germinated according to Kruegel et al. (2002) and cultivated in 1L-pots. For details on the cultivation and fertilization, see the Supplemental Procedures. The transgenic lines were homozygous, near-isogenic to WT and representative of several independent transformation events.

Plant treatment

Pre-experiment to determine elicitation time-points

Seven days after transfer to 1L single pots, rosette-stage plants were pulse-labeled with 5.1 mg 15N in 50 mL of a 0.694 g*L−1 solution of K15NO3 (modified from Van Dam and Baldwin 2001) and the oldest sink leaf (hereafter, younger rosette leaf, yRL) and the youngest source leaf (hereafter, older rosette leaf, oRL, Pluskota et al. 2007) were labeled for later sampling. The leaves and roots were harvested 0, 4, 12 h, and 4, 7 and 10 days after the 15N-pulse. Roots were washed to remove excess soil and all samples were dried for 48h at 60°C. Between 3 and 10 days after the pulse, the leaves and roots had a constant 15N-concentration (Fig. 1b), indicating that an equilibrium had been reached. This time-period was chosen for further experiments (Fig. 1b, indicated by the grey arrows) since a stable 15N-incorporation facilitates the analysis of proportional allocation to single compounds. The N-pulse did not have any obvious effects on plant growth.

Pulse-labeling experiments

Three days after the 15N pulse the oldest sink, youngest source and transition leaf at the time-point of labeling were wounded with a pattern wheel and treated with M. sexta oral secretion (OS, 10 μL per leaf*day−1, 1:5 diluted) on three consecutive days (Ullmann-Zeunert et al. 2012). Unelicited plants were used as controls. For the whole-shoot N analysis, the aboveground biomass of control and elicited plants was harvested 4 days after the first elicitation and dried as above.

For the N-partitioning analysis, both the locally elicited yRL and oRL were harvested 4 days after the first elicitation and flash-frozen in liquid N2. After stalk elongation, the first stem leaf (S1) was harvested when it reached the source-sink transition stage. For all three leaves, only the right leaf blade was harvested to standardize sampling and minimize changes in source-sink relationships due to repeated sampling. Harvest time-points of the S1 leaf differed depending on plant development. The first mature seed capsules were harvested at the day of opening: seeds were counted, weighed and analyzed for N content. For the kinetic analysis, plants received a 15N pulse and were elicited as described above, and the locally elicited yRL was harvested 0, 1, 3, 4 and 7 days after the first elicitation (Fig. 1b). Sample size for all analyses was 5.

Protein extraction and quantification

The TSP and RuBisCO LSU and SSU were extracted and quantified by Bradford assay and LC-MSE, respectively, as described by Ullmann-Zeunert et al. (2012). The 15N-incorporation of RuBisCO was determined with ProSipQuant (Taubert et al. 2011).

Metabolite extraction and quantification

Small metabolites were extracted as in Gaquerel et al. (2010) and analyzed by UPLC/UV/ToF-MS, using a Dionex RSLC system with a Diode Array Detector (Dionex, Sunnyvale, USA) and a Micro-ToF Mass Spectrometer (BrukerDaltonik, Bremen, Germany). Further details on instrument parameters and quantification are described in the Supplemental Procedures. Average mass spectra were extracted for 15N-incorporations using ProSipQuant (Taubert et al. 2011), modified for small metabolites based on compound sum formula.

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry Analysis (IRMS)

The IRMS sample preparation, analysis and following calculations of total N content (% dry mass) and 15N-incorporation were carried out as described in Meldau et al. (2012).

Statistical Analysis

The R environment was used for statistical analysis (Team 2009). For ANOVA and ANCOVA analyses, if the assumption of homoscedasticity of variances was violated or the residuals did not follow a normal distribution, response variables were transformed prior to the analyses using Box Cox transformation (see Appendix S1). The Box-Cox-lambda was estimated using Venables’ and Ripley’s MASS library for R. All ANOVA models were simplified to the minimum adequate model using Aikaike’s information criterion (Ronchetti 1985). For the correlation analysis (Fig. 4a, heatmaps) the data were imported into the environment and vectors containing the following variables generated: N-rest protein μg/mg, N-RuBisCO LSU μg/mg, N-RuBisCO SSU μg/mg, N-nicotine μg/mg, N-CP μg/mg, and N-DCS μg/mg. These vectors were pairwise correlated, calculating Kendall’s τ coefficient (Kendall 1938). In contrast to Pearson’s correlation coefficient Kendall’s τ is more robust and not sensitive to the data distribution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Franziska Hufsky for bioinformatics help with RuBisCO quantification and Dr. Matthias Schöttner for technical support with metabolite measurements. This research was supported by the Max Planck Society, M.A.S. by a grant of the International Max Planck Research School and I.T.B by an advanced ERC grant, ClockworkGreen (293926).

Footnotes

Supplemental Procedures

Supplemental Figure Legends

Figure S1: The dry mass and the absolute amount of nitrogen (N) of the shoot are not influenced by genotype.

Figure S2: Average leaf size produced by transgenic (irLOX3, irMYB8) and WT plants with and without the W+OS treatment.

Figure S3: Silencing of LOX3 and MYB8 alters the absolute pools of RuBisCO (a) and N-containing small metabolites (b) in leaves.

Figure S4: Reproductive timing and output produced by transgenic (irLOX3, irMYB8) and WT plants with and without the W+OS treatment.

Figure S5: Increased N investment into nicotine, CP and DCS is accompanied by a decreased N investment into RuBisCO.

Figure S6: The decrease of N investment into protein pools is greater than the amount of N required for the biosynthesis of the N-containing defense metabolites.

Figure S7:15N incorporation in the yRL is not influenced by treatment or genotype.

Appendix S1: Supplemental Statistical Information

References

- Allen DK, Laclair RW, Ohlrogge JB, Shachar-Hill Y. Isotope labelling of Rubisco subunits provides in vivo information on subcellular biosynthesis and exchange of amino acids between compartments. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:1232–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmann S, Halitschke R, Schuurink RC, Baldwin IT. Oxylipin channelling in Nicotiana attenuata: lipoxygenase 2 supplies substrates for green leaf volatile production. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:2028–2040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin IT. Inducible nicotine production in native Nicotiana as an example of adaptive phenotypic plasticity. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999;25:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin IT, Gorham D, Schmelz EA, Lewandowski CA, Lynds GY. Allocation of nitrogen to an inducible defense and seed production in Nicotiana attenuata. Oecologia. 1998;115:541–552. doi: 10.1007/s004420050552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin IT, Hamilton W. Jasmonate-induced responses of Nicotiana sylvestris results in fitness costs due to impaired competitive ability for nitrogen. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000;26:915–952. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin IT, Karb MJ, Ohnmeiss TE. Allocation of 15N from nitrate to nicotine - production and turnover of a damage-induced mobile defense. Ecology. 1994;75:1703–1713. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin IT, Ohnmeiss TE. Coordination of photosynthetic and alkaloidal responses to damage in uninducible and inducible Nicotiana sylvestris. Ecology. 1994;75:1003–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzaz FA, Chiariello NR, Coley PD, Pitelka LF. Allocating rescources to reproducation and defense. Bioscience. 1987;37:58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chapin FS, Schulze ED, Mooney HA. The ecology and economics of storage in plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1990;21:423–447. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- Diezel C, von Dahl CC, Gaquerel E, Baldwin IT. Different lepidopteran elicitors account for cross-talk in herbivory-induced phytohormone signaling. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1576–1586. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.139550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ. Most abundant protein in the world. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1979;4:241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Frost CJ, Hunter MD. Herbivore-induced shifts in carbon and nitrogen allocation in red oak seedlings. New Phytol. 2008;178:835–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaquerel E, Heiling S, Schoettner M, Zurek G, Baldwin IT. Development and validation of a liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry method for Induced changes in Nicotiana attenuata leaves during simulated herbivory. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:9418–9427. doi: 10.1021/jf1017737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri AP, Wuensche H, Mitra S, Zavala JA, Muck A, Svatos A, Baldwin IT. Molecular interactions between the specialist herbivore Manduca sexta (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae) and its natural host Nicotiana attenuata. VII. Changes in the plant’s proteome. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1621–1641. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.088781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez S, Ferrieri RA, Schueller M, Orians CM. Methyl jasmonate elicits rapid changes in carbon and nitrogen dynamics in tomato. New Phytol. 2010;188:835–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez S, Steinbrenner AD, Osorio S, Schueller M, Ferrieri RA, Fernie AR, Orians CM. From shoots to roots: transport and metabolic changes in tomato after simulated feeding by a specialist lepidopteran. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2012;144:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Halitschke R, Gase K, Hui DQ, Schmidt DD, Baldwin IT. Molecular interactions between the specialist herbivore Manduca sexta (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae) and its natural host Nicotiana attenuata. VI. Microarray analysis reveals that most herbivore-specific transcriptional changes are mediated by fatty acid-amino acid conjugates. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:1894–1902. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.018184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halitschke R, Ziegler J, Keinanen M, Baldwin IT. Silencing of hydroperoxide lyase and allene oxide synthase reveals substrate and defense signaling crosstalk in Nicotiana attenuata. Plant J. 2004;40:35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil M, Baldwin IT. Fitness costs of induced resistance: emerging experimental support for a slippery concept. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)02186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herms DA, Mattson WJ. The dilemma of plants - to grow or defend. Q. Rev. Biol. 1992;67:283–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hibi N, Higashiguchi S, Hashimoto T, Yamada Y. Gene-expression in tobacco low-nicotine mutants. Plant Cell. 1994;6:723–735. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.5.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Suzuki Y, Mae T, Makino A. Changes in the synthesis of rubisco in rice leaves in relation to senescence and N influx. Ann. Bot. 2008;101:135–144. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura S, Kanesaki Y, Ohnuma M, Inouye T, Sekine Y, Fujiwara T, Kuroiwa T, Tanaka K. R2R3-type MYB transcription factor, CmMYB1, is a central nitrogen assimilation regulator in Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12548–12553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902790106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru K, Kobayashi N, Ono K, Yano M, Ohsugi R. Are contents of Rubisco, soluble protein and nitrogen in flag leaves of rice controlled by the same genetics? J. Exp. Bot. 2001;52:1827–1833. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.362.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karban R, Baldwin IT. Induced responses to herbivory. Univ. of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H, Heinzel N, Schoettner M, Baldwin IT, Galis I. R2R3 NaMYB8 regulates the accumulation of phenylpropanoid-polyamine conjugates, which are essential for local and systemic defense against insect herbivores in Nicotiana attenuata. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1731–1747. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.151738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall M. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika. 1938;30:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler A, Halitschke R, Baldwin IT. Silencing the jasmonate cascade: Induced plant defenses and insect populations. Science. 2004;305:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.1096931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruegel T, Lim M, Gase K, Halitschke R, Baldwin IT. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Nicotiana attenuata, a model ecological expression system. Chemoecology. 2002;12:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lou YG, Baldwin IT. Nitrogen supply influences herbivore-induced direct and indirect defenses and transcriptional responses to Nicotiana attenuata. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:496–506. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynds GY, Baldwin IT. Fire, nitrogen, and defensive plasticity in Nicotiana attenuata. Oecologia. 1998;115:531–540. doi: 10.1007/PL00008820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Harada M, Kaneko K, Mae T, Shimada T, Yamamoto N. Whole-plant growth and N allocation in transgenic rice plants with decreased content of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase under different CO2 partial pressures. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 2000;27:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K. Relation between nitrogen and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in rice leaves from emergence through senescence. Plant Cell Physiol. 1984;25:429–437. [Google Scholar]

- Matt P, Krapp A, Haake V, Mock HP, Stitt M. Decreased Rubisco activity leads to dramatic changes of nitrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism and the levels of phenylpropanoids and nicotine in tobacco antisense RBCS transformants. Plant J. 2002;30:663–677. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloud ES, Baldwin IT. Herbivory and caterpillar regurgitants amplify the wound-induced increases in jasmonic acid but not nicotine in Nicotiana sylvestris. Planta. 1997;203:430–435. [Google Scholar]

- McKey D. Adaptive patterns in alkaloid physiology. Am. Nat. 1974;108:305–320. [Google Scholar]

- McKey D. Distribution of secondary compounds within plants. In: Rosenthal GA, Janzen DH, editors. Herbivores: Their interaction with secondary plant metabolites. Academic Press; New York: 1979. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Meldau S, Ullmann-Zeunert L, Govind G, Bartram S, Baldwin IT. Basal and herbivory-induced defense trade-offs are mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinases, jasmonic acid and salicylic acid in the native tobacco, Nicotiana attenuata. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard P. The accumulation and storage of nitrogen by herbaceous plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1988;11:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake K, Ito T, Senda M, Ishikawa R, Harada T, Niizeki M, Akada S. Isolation of a subfamily of genes for R2R3 MYB transcription factors showing up-regulated expression under nitrogen nutrient-limited conditions. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003;53:237–245. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000009296.91149.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mole S. Trade-offs and constraints in plant-herbivore defense theory - a life-history perspective. Oikos. 1994;71:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnmeiss TE, Baldwin IT. Optimal Defense theory predicts the ontogeny of an induced nicotine defense. Ecology. 2000;81:1765–1783. [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake N, Sato T, Fujikake H, Sueyoshi K, Ohyama T, Ishioka NS, Watanabe S, Osa A, Sekine T, Matsuhashi S, Ito T, Mizuniwa C, Kume T, Hashimoto S, Uchida H, Tsuji A. Rapid N transport to pods and seeds in N-deficient soybean plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2001;52:277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onkokesung N, Galis I, von Dahl CC, Matsuoka K, Saluz H-P, Baldwin IT. Jasmonic acid and ethylene modulate local responses to wounding and simulated herbivory in Nicotiana attenuata leaves. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:785–798. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onkokesung N, Gaquerel E, Kotkar H, Kaur H, Baldwin IT, Galis I. MYB8 controls inducible phenolamide levels by activating three novel hydroxycinnamoyl-coenzyme A:polyamine transferases in Nicotiana attenuata. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:389–407. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.187229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orians CM, Thorn A, Gomez S. Herbivore-induced resource sequestration in plants: why bother? Oecologia. 2011;167:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00442-011-1968-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluskota WE, Qu N, Maitrejean M, Boland W, Baldwin IT. Jasmonates and its mimics differentially elicit systemic defence responses in Nicotiana attenuata. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:4071–4082. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston CA, Baldwin IT. Positive and negative signals regulate germination in the post-fire annual, Nicotiana attenuata. Ecology. 1999;80:481–494. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades DF. Evolution of plant chemical defense against herbivores. In: Rosenthal GA, Janzen DH, editors. Herbivores: Their interaction with secondary plant metabolites. Academic Press; New York: 1979. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ronchetti E. Robust model selection in regression. Stat. Probab. Lett. 1985;3:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schittko U, Hermsmeier D, Baldwin IT. Molecular interactions between the specialist herbivore Manduca sexta (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae) and its natural host Nicotiana attenuata. II. Accumulation of plant mRNAs in response to insect-derived cues. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:701–710. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwachtje J, Minchin PEH, Jahnke S, van Dongen JT, Schittko U, Baldwin IT. SNF1-related kinases allow plants to tolerate herbivory by allocating carbon to roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12935–12940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602316103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J, Gleadow RM, Woodrow IE. Allocation of nitrogen to chemical defence and plant functional traits is constrained by soil N. Tree Physiol. 2010;30:1111–1117. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibbe M, Qu N, Galis I, Baldwin IT. Induced plant defenses in the natural environment: Nicotiana attenuata WRKY3 and WRKY6 coordinate responses to herbivory. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1984–2000. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamp N. Out of the quagmire of plant defense hypotheses. Q. Rev. Biol. 2003;78:23–55. doi: 10.1086/367580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrenner AD, Gomez S, Osorio S, Fernie AR, Orians CM. Herbivore-induced changes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) primary metabolism: A whole plant perspective. J. Chem. Ecol. 2011;37:1294–1303. doi: 10.1007/s10886-011-0042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steppuhn A, Gase K, Krock B, Halitschke R, Baldwin IT. Nicotine’s defensive function in nature. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:1074–1080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Krapp A. The interaction between elevated carbon dioxide and nitrogen nutrition: the physiological and molecular background. Plant Cell Environ. 1999;22:583–621. [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Schulze D. Does Rubisco control the rate of photosynthesis and plant-growth - an exercise in molecular ecophysiology. Plant Cell Environ. 1994;17:465–487. [Google Scholar]

- Stork W, Diezel C, Halitschke R, Galis I, Baldwin IT. An ecological analysis of the herbivory-elicited JA burst and its metabolism: plant memory processes and predictions of the moving target model. Plos One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano A, Kakehi JI, Takahashi T. Thermospermine is not a minor polyamine in the plant kingdom. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:606–616. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubert M, Jehmlich N, Vogt C, Richnow HH, Schmidt F, von Bergen M, Seifert J. Time resolved protein-based stable isotope probing (Protein-SIP) analysis allows quantification of induced proteins in substrate shift experiments. Proteomics. 2011;11:2265–2274. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2009. http://www.r-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Trumble JT, Kolodnyhirsch DM, Ting IP. Plant compensation for arthropod herbivory. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1993;38:93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ullmann-Zeunert L, Muck A, Wielsch N, Hufsky F, Stanton MA, Bartram S, Böcker S, Baldwin IT, Groten K, Svatos A. Determination of 15N-Incorporation into plant proteins and their absolute quantitation: A new tool to study nitrogen flux dynamics and protein pool sizes elicited by plant–herbivore interactions. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:4947. doi: 10.1021/pr300465n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam NM, Baldwin IT. Competition mediates costs of jasmonate-induced defences, nitrogen acquisition and transgenerational plasticity in Nicotiana attenuata. Funct. Ecol. 2001;15:406–415. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam NM, Hermenau U, Baldwin IT. Instar-specific sensitivity of specialist Manduca sexta larvae to induced defences in their host plant Nicotiana attenuata. Ecol. Entomol. 2001;26:578–586. [Google Scholar]

- van Dam NM, Oomen MWAT. Root and shoot jasmonic acid applications differentially affect leaf chemistry and herbivore growth. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008;3:91–98. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.2.5220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelckel C, Baldwin IT. Generalist and specialist lepidopteran larvae elicit different transcriptional responses in Nicotiana attenuata, which correlate with larval FAC profiles. Ecol. Lett. 2004a;7:770–775. [Google Scholar]

- Voelckel C, Baldwin IT. Herbivore induced plant vaccination. Part II. Array-studies reveal the transience of herbivore-specific transcriptional imprints and a distinct imprint from stress combinations. Plant J. 2004b;38:650–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelckel C, Krugel T, Gase K, Heidrich N, van Dam NM, Winz R, Baldwin IT. Anti-sense expression of putrescine N-methyltransferase confirms defensive role of nicotine in Nicotiana sylvestris against Manduca sexta. Chemoecology. 2001;11:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Woldemariam MG, Baldwin IT, Galis I. Transcriptional regulation of plant inducible defenses against herbivores: a mini-review. J. Plant Interact. 2011;6:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Zangerl AR, Hamilton JG, Miller TJ, Crofts AR, Oxborough K, Berenbaum MR, de Lucia EH. Impact of folivory on photosynthesis is greater than the sum of its holes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1088–1091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022647099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala JA, Patankar AG, Gase K, Baldwin IT. Constitutive and inducible trypsin proteinase inhibitor production incurs large fitness costs in Nicotiana attenuata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004a;101:1607–1612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305096101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala JA, Patankar AG, Gase K, Hui DQ, Baldwin IT. Manipulation of endogenous trypsin proteinase inhibitor production in Nicotiana attenuata demonstrates their function as antiherbivore defenses. Plant Physiol. 2004b;134:1181–1190. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.035634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.