Abstract

Congenital heart disease is diagnosed in 0.4% to 5% of live births and presents unique challenges to the pediatric anesthesiologist. Furthermore, advances in surgical management have led to improved survival of those patients, and many adult anesthesiologists now frequently take care of adolescents and adults who have previously undergone surgery to correct or palliate congenital heart lesions. Knowledge of abnormal heart development on the molecular and genetic level extends and improves the anesthesiologist's understanding of congenital heart disease. In this paper we aim to review current knowledge pertaining to genetic alterations and their cellular effects that are involved in the formation of congenital heart defects. Given that congenital heart disease can currently only occasionally be traced to a single genetic mutation, we highlight some of the difficulties that researchers face when trying to identify specific steps in the pathogenetic development of heart lesions.

Introduction

The embryonic development of the human heart is a complex process. Considering the hearts seemingly simple function of pumping oxygen- and nutrient-rich blood, its development requires multiple critical and time-sensitive steps, all of which need to occur in the correct order to avoid the structural and functional abnormalities collectively described as congenital heart disease. Depending on the definition used, the incidence of congenital heart disease is 0.4% to 5% of live births.1 Low incidence rates reported by earlier studies are attributed to the then limited availability of diagnostic modalities such as echocardiography. Studies examining severe diseases presenting only in infancy had lower incidence rates than those that included less severe abnormalities presenting later in life.1

From the practicing physician's point of view, a sound understanding of cardiac development, including genetics, molecular cell biology, embryology, systems biology and anatomy, allows for a better appreciation of disruptions in developmental patterns and the resulting pathophysiology of congenital heart disease. Yet there are three hindrances to understanding the embryology of congenital heart disease: 1) multiple names exist for the same cardiac structures; 2) the molecular biology is extraordinarily complex; and 3) the causes of congenital heart disease are poorly established. We aim to provide a review of the current understanding of the molecular processes and disruptions that lead to congenital heart disease rather than to review the pathophysiologic effects of specific defects which are delineated in major textbooks.2-4

Structural Heart Development – A Brief Overview

A detailed account of the development of the human heart is not the purpose of this manuscript but some knowledge is required to understand the molecular biology. The interested reader is directed to embryology textbooks or excellent reviews on this topic .5,6 However, to understand the concepts described here, a basic knowledge of the structural development of the heart is necessary. Heart development, in its simplest terms, can be put into the context of nine major steps.

Formation of the three germ layers (gastrulation)

Establishment of the first and second heart fields

Formation of the heart tube

Cardiac looping, convergence, and wedging

Formation of septa (common atrium, atrioventricular canal)

Development of the outflow tract

Formation of cardiac valves

Formation of vasculature (coronary arteries, aortic arches, sinus venosus)

Formation of the conduction system

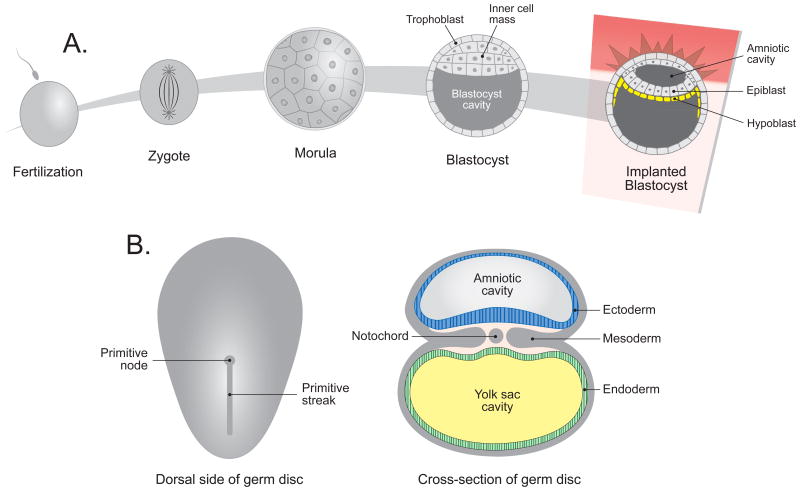

Fertilization, the fusion of gametes (sperm and oocyte), creates a zygote and initiates embryogenesis. The zygote proceeds through multiple stages via mitotic divisions. After reaching the blastocyst stage, the cell mass implants into the uterus. Early after uterine implantation, the rudimentary germ disc consists of two cell layers, the epiblast and hypoblast (Figure 1A). A groove called the primitive streak forms in the epiblast and extends from the caudal region, cranially towards the primitive node located between the oropharyngeal (cranial) and cloacal (caudal) membranes.

Figure 1.

Overview of human embryogenesis. A) Step-wise progression from fertilization (fusion of sperm and oocyte to create a zygote) to morula and blastocyst with blastocyst implantation into uterus. B) Formation of the germ disc with three germ cell layers.

Formation of the primitive streak defines the major body axes; the cranio-caudal, ventral-dorsal and left-right axes thus orienting cellular migration and proliferation.

The three germ cell layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm) are developed within a cup-shaped structure in a process called gastrulation (Figure 1B). Starting on day sixteen after fertilization, some epiblast cells around the primitive streak detach and migrate between the epiblast and hypoblast cell layer. These migrating cells form endoderm and mesoderm, while the epiblast cells that remain in the initial cell layer become ectoderm. The mesodermal cells differentiate into four cell populations - cardiogenic mesoderm, and the paraxial, intermediate and lateral plate mesoderm.

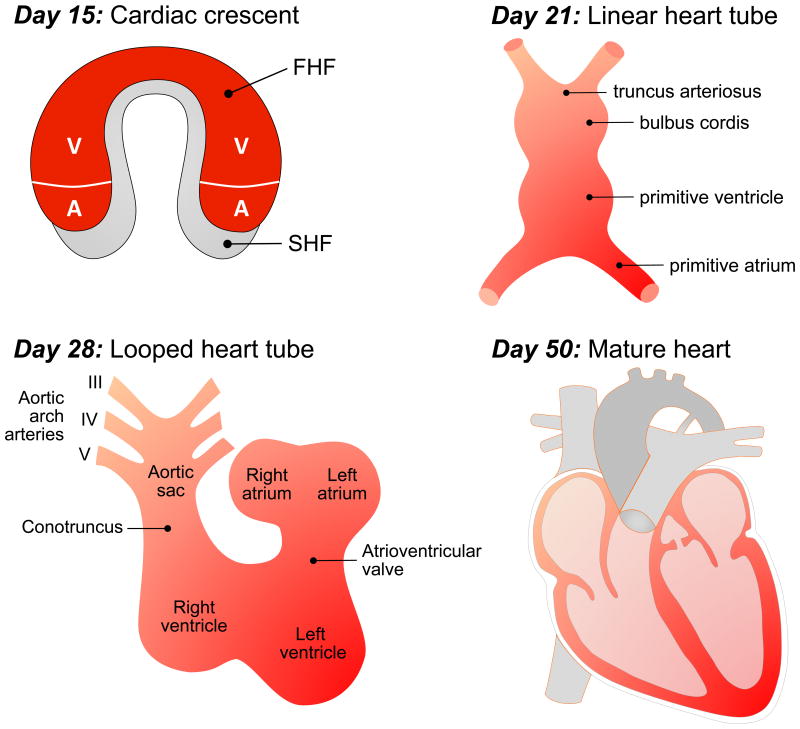

Progenitor cardiogenic mesodermal cells in the cranial part of the primitive streak migrate cranio-laterally and form a crescent-shaped mantle around the cranial neural folds called the first heart field. A secondary heart field forms in the pharyngeal mesoderm, medial and caudal from the first heart field. The resulting cardiac crescent at day 15 is depicted in Figure 2A. The primitive heart begins to beat about day 21, and starts pumping blood by day 24-25. At the same time, a portion of the primitive streak induces the overlying ectoderm to thicken as the neural plate, the precursor of the central nervous system. Not long after, the rudimentary skeletal notochord is formed.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of cardiac embryology. A) Cardiac crescent at day 15. The first heart field is specified to form particular segments of the linear heart tube. The second heart field is located medial and caudal of the first heart field and will later contribute cells to the arterial and venous pole. B) By day 21, cephalocaudal and lateral folding of the embryo establishes the linear heart tube with its arterial (truncus arteriosus) and venous (primitive atrium) poles. C) By day 28, the linear heart tube loops to the right (D-loop) to establish the future position of the cardiac regions (atria, ventricles, outflow tract). D) By day 50, the mature heart has formed. The chambers and outflow tract of the heart are divided by the atrial septum, the interventricular septum, two atrioventricular valves (tricuspid valve, mitral valve) and two semilunar valves (aortic valve, pulmonary valve). Adapted in modified form from Lindsey SE, Butcher JT, Yalcin HC: Mechanical regulation of cardiac development. Front Physiol 5:318, 2014.

During the fourth week of gestation, the ecto-, meso- and endodermal cell layers formed in the third week differentiate to form the primordia of most of the major organ systems of the body including the heart. Formation of the heart tube is a complex three-dimensional process that, like for the development of most other organs, uses all three germ layers – the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. Embryonic growth includes folding in the cranio-caudal and lateral axes that brings the endocardial tubes, situated in the splanchnic layer of the lateral plate mesoderm on both sides, together to the midline where fusion to a single endocardial tubes occurs (Figure 2B). The endocardial tube consists of the myocardium formed by myocardial cells and an endocardium formed by endothelial cells. An extracellular matrix, called cardiac jelly, separates those two cell types. The epicardium is later formed by migration of proepicardial precursor cells.7

In the past, it was assumed that the heart tube contained all elements necessary to form the final four-chambered heart. New research shows that the initial heart tube, formed by cells from the first heart field, ultimately ends up forming only a small part of the four-chambered heart. While cells from the first heart field provide a scaffold, the majority of the heart is formed by migration of precursor cell originating from the second heart field leading to elongation of the heart tube.8-10 The rearrangement of the endocardial tube position is crucial for the formation of the four heart chambers along with the inflow and outflow connections to the vasculature. Cardiac looping is driven by elongation of the endocardial tube achieved by migration of precursor cells. From days 23 to 28, the endocardial tube bends to assume the cardiac loop configuration (Figure 2C). Movement of the outflow tract and the atrioventricular canal into a more midline position aligns those structures; this process is termed convergence. In a final step, separation (septation) of the primitive ventricles and outflow tract into systemic (aorta) and pulmonary (pulmonary artery) trunks are created by a process called wedging which describes the counterclockwise rotation of the outflow tract with movement of the future aortic valve position behind the pulmonary trunk and formation of the proximal (conus) and distal (truncus) components of the outflow tract.

Atrial septation begins with the septum primum growing from the base towards the apex in the fourth and fifth weeks of gestation. The septum primum divides the left and right atrium except for two distinct sites. Before reaching the endocardial cushion, a small hole persists termed the ostium primum. In addition, cell death occurs in the more cranial part, which forms fenestrations that become the ostium secundum. The septum primum is later closed by fusion of the anterior and posterior endocardial cushions. Around day 33, a second septum forms on the right atrial side. It initially has the shape of a crescent and grows to abut the ostium secundum, forming a valve that allows blood to pass from the right to the left atrium – the foramen ovale. However, the two septa do not fuse until after birth, allowing for right-to-left shunting of placental and systemic venous blood during gestation.

The atrioventricular canal is partitioned into the left and right ventricle by the interventricular septum, which forms from four atrioventricular endocardial cushions (anterior, posterior and two lateral). Endocardial cushions, local tissue swellings located in the atrioventricular canal and proximal ventricular outflow tracts become populated by endocardial cells which undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation controlled by transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and neurogenic locus notch homolog protein (Notch) signalling11, detach and migrate into the cushion matrix. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation describes a process in which epithelial cells transform into mesenchymal stem cells by losing cell adhesion molecules and cell polarity while gaining the ability to migrate and invade tissue planes.

The atrioventricular valves develop from mesenchymal cells of the endocardial atrioventricular cushions during the fifth and sixth weeks of gestation.12 Growth of the superior, inferior and lateral atrioventricular cushions partition the common atrioventricular canal into the left and right atrioventricular canal. The final steps of mitral and tricuspid valve formation include migration of epicardial cells onto cushions and parietal valve leaflets. For the development of the outflow tract cushions, endocardial cells that underwent epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation cooperate with cardiac neural crest cells which control the correct septation of the common outflow tract, contribute to the aortic and pulmonic valve leaflets and form part of the superior aspect of the ventricular septum.13

During expansion of the primitive right and left ventricles and the addition of migrating myocardial cells, a muscular interventricular septum forms from the primary fold or ring that partially separates the ventricles. By growing from the apex towards the atrioventricular endocardial cushions the muscular interventricular septum is formed. A small gap above the muscular interventricular septum, called the interventricular foramen, is later closed by fusion of the superior (also called dorsal or posterior) and inferior (also called ventral or anterior) atrioventricular endocardial cushions with some contribution from the outflow tract cushions. This yields the membranous part of the atrioventricular septum.14

Prior to the convergence and wedging stages, the outflow tract situated above the future right ventricle is not divided into two distinct pulmonary or systemic tracts. During the seventh and eighth weeks, the outflow tract of the heart completes the process of septation and division via two processes. The first is the appearance of the aorticopulmonary septum which partitions the outflow tract and gives rise to the aorta and pulmonary artery. It develops from truncus swellings (situated right superiorly and left inferiorly) that grow and connect in a spiral-like fashion. During this process, remodeling of the distal outflow tract cushion tissue (truncal cushions) results in the formation of the semilunar valves of the aorta and pulmonary artery. The second process, which is also involved in ventricular septation, is the growth and fusion of the proximal outflow tract cushions (conal cushions); this creates the outlet septum, resulting in the separation of left and right ventricular outflow tracts. Complete ventricular septation depends on fusion of the outflow tract (conotruncal) septum, the muscular ventricular septum, and the atrioventricular cushion tissues.

The vascular system originates from the first heart field. Around day 18, progenitor cells of the primary heart field are induced to form cardiac myoblasts which give rise to paired dorsal aortae. Later, starting at day 28, pharyngeal arches form. Those pharyngeal arches are accompanied by a cranial nerve and an aortic arch. Aortic arches appear sequentially in a cranio-caudal order and connect the aortic sac (distal part of the truncus arteriosus) to the bilateral dorsal aortae. The five paired arches are numbered I, II, III, IV and VI (the fifth arch never forms) and give rise to the maxillary arteries (I), hyoid and stapedial arteries (II), common carotid and first part of internal carotid arteries (III), aortic arch (left IV), right subclavian artery (right IV), left pulmonary artery and ductus arteriosus (left VI) and right pulmonary artery (right VI).

The coronary vasculature is derived from proepicardial progenitor cells and venous endothelial angioblasts originating from the sinus venosus. The epithelial progenitors undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation. After formation of the main coronary vessels, the coronary system connects to the aorta by invasion of arterial endothelial cells into the aorta. By day 50, the heart has developed to its mature form (Figure 2D).

Molecular Biology and Genetics of Cardiac Development

Macroscopic structural heart development as reviewed in the previous section is dependent upon cellular proliferation, specification, migration, and eventual morphogenesis of cardiac structures. Specialized cells that arise from stem cells determine this development. Cardiac progenitor cell populations differentiate into the cell types of the developing and adult heart, notably the cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, valvular interstitial cells, conduction system, endocardium and pericardium, amongst others. Dividing and growing cells form the human heart require a genetic blueprint to determine the shape, location and task for each individual unit.

Genetic nomenclature distinguishes a gene and a protein in a standard format. A human gene is presented in italic uppercase letters (e.g., GATA4), while the protein derived from this gene is written in non-italic uppercase letters (e.g., GATA4). Much of what is known about vertebrate embryogenesis comes from mouse and chick development. The mouse serves as a useful model because of its genetic similarity to humans and because the possibility of introducing genetic disruption. The chicken is often used to study embryogenesis, as it is even more amenable to genetic disruption than mice. Mouse proteins have the same symbol as the human counterpart (GATA4), while mouse gene symbols are in italic with the first letter in uppercase and the following letters in lowercase (Gata4). Protein and gene nomenclature for the chicken follows the human conventions (e.g. protein in non-italic uppercase letters and gene in italic uppercase letters). Complicating this, sometimes mouse and chick genes and proteins have different names from homologous human genes and proteins.

During transcription, the DNA is translated into a nuclear ribonucleic acid (RNA) that is modified by splicing of non-coding, intervening sequences (introns). This yields the messenger RNA which consists of coding sequences (exons). The mRNA leaves the nucleus and docks with ribosomes in the cytoplasm. Ribosomes initiate translation, the process of decoding RNA base triplets (codons) into amino acid sequences, thus forming a protein. The finished protein assumes its predetermined three-dimensional structure and is ready for its intended task.

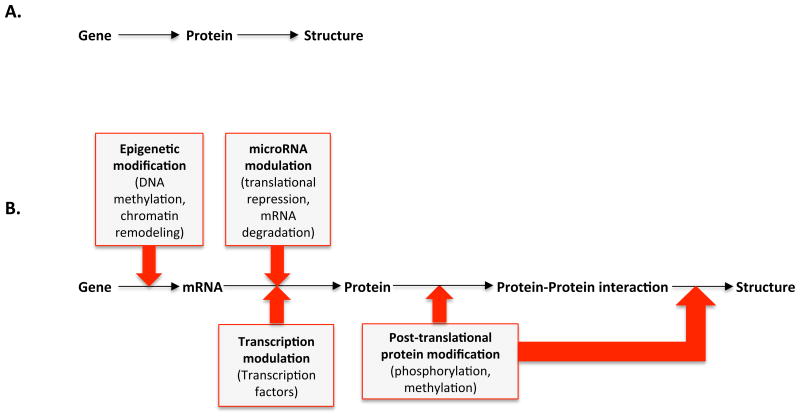

But DNA is not the sole controlling blueprint for embryogenesis. While a certain gene carries the code for a certain protein, a variety of modifications can take place at different steps. These steps include the rate at which a gene is being transcribed, a process controlled by transcription factors that bind to DNA sequences and either enhance or silence gene expression into mRNA. The ability of signaling proteins to access the controlling sequence for transcription of DNA into mRNA is actively controlled by histone proteins and physical coiling of parental DNA to limit or enhance transcription – a process called epigenetics. Further, differential splicing can re-arrange exons in an mRNA and result in many isoforms of a protein, some with different functions. Silencing of mRNA by non-protein-coding can occur from small interfering RNAs (si), micro RNAs (mi), and long non-coding RNAs (lnc), respectively. Other mechanisms can alter the amount of a protein translated. Finally, after translation, proteins can undergo modifications, such as phosphorylation, that alter its activity or function. Proteins can assume a variety of roles such as structural proteins, transcription factors, cofactors, receptors, ligands and signaling proteins. The seemingly linear path between gene and protein is complex and open to variation that can result in structural and functional heart disease, even in the absence of a protein-coding genetic mutation. Figure 3 gives an overview of gene transcription and translation along with influencing factors.

Figure 3.

A simplified depiction of formation of protein structures. A) A gene is transcribed and translated to form a protein. Proteins are then assembled to larger structures or functional enzymes. B) A more detailed depiction of the process in A) which includes influencing factors such as modulation and modification at different levels.

Cell Signaling in Embryogenesis

DNA provides a blueprint for cell function and behavior, but how can it be explained that there is such a variety between different cells that are organized in multiple different ways? Why are cells of the same embryonic origin able to perform different tasks? Further, how do growing cells not behave like malignant cancer cells and how do they stop growing after reaching a certain cell mass or a particular location? All of this can be explained by cell signaling.

To properly orient cellular migration and proliferation, the major body axes (i.e. the cranio-caudal, ventral-dorsal and left-right axes) need to be established. Subsequently, a complex and highly regulated network of signaling pathways controls cellular migration and proliferation. Two concepts are worth emphasizing at this point; there is cell-type specific expression of proteins involved in cell expansion and migration, and there is a concentration gradient for signaling proteins, whereby cells in close proximity to a cell that secretes signaling proteins see higher concentrations of these proteins. Both of these mechanisms are responsible for specific anatomical development of the embryo.

The establishment of a left-right body axis (laterality) is an important and central theme during embryonic development that explains organ asymmetries in the adult organism (heterotaxy). How does the body know that the spleen belongs on the left side while the liver is located on the right? Why does the left lung consist of two lobes while the right is made up of three lobes? Laterality occurs early in embryonic development. Around the third week of gestation, the embryo has reached the germ disc stage. The primitive streak (consisting of the primitive groove, primitive pit and primitive node) forms in the mid-sagittal plane at the caudal aspect of the germ disc and migrates cranially. The primitive streak establishes the cranial-caudal, left-right and medial-lateral axes. The primitive node, defined as the cranial end of the primitive streak, possesses organizer activity determining left-right laterality establishment.

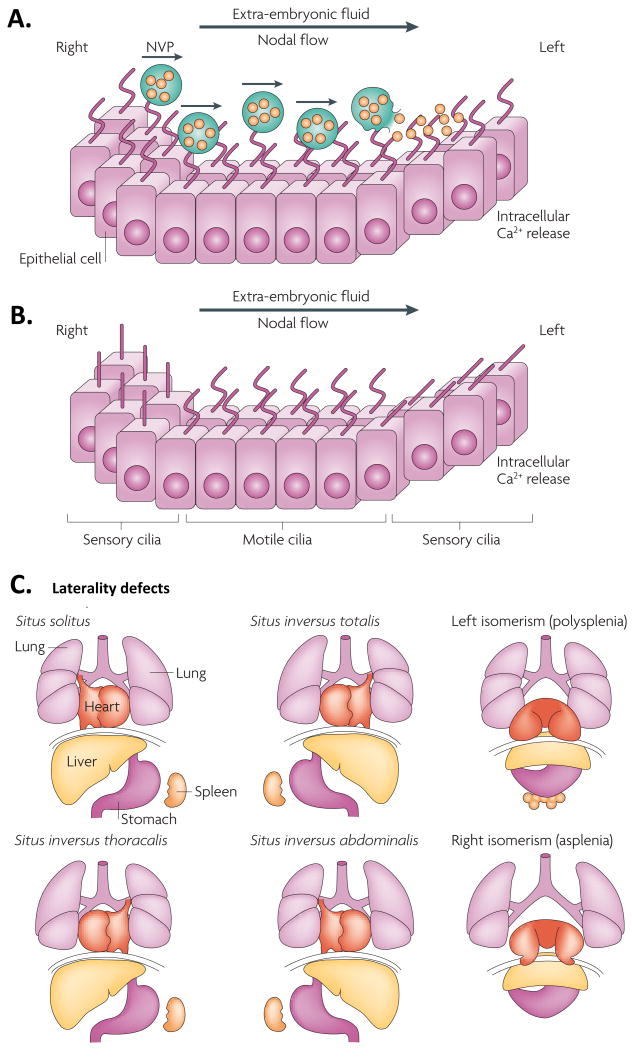

The primitive node contains two types of cilia: motile cilia, predominantly in the central region, and immotile mechanosensory cilia in the peripheral region of the node.15 The design of the motile cilia is unique: they rotate in a clockwise fashion and are tilted 40 degrees posterior, making the rightward sweep coming close to the surface while the leftward sweep leads away from the surface.16 This configuration results in a laminar leftward fluid. The final pathway of how cells situated on the left side receive the left-right pattern signal is debated. Four theories prevail: 1) creation of a left-to-right signaling molecule gradient; 2) movement of signaling-molecule-containing membrane-covered nodal vesicular parcels (NVP) to the left; 3) activation of mechanosensory cilia on the left and 4) activation of chemosensory ciliae on the left (Figure 4A and B).15-17

Figure 4.

Human laterality disorders and current models for establishing left-right asymmetry. By their vigorous circular movements, motile monocilia at the embryonic node generate a leftward flow of extra-embryonic fluid (nodal flow). A) The nodal vesicular parcel (NVP) model predicts that vesicles filled with morphogens (such as sonic hedgehog and retinoic acid) are secreted from the right side of the embryonic node and transported to the left side by nodal flow, where they are smashed open by force. The released contents probably bind to specific transmembrane receptors in the axonemal membrane of cilia on the left side. The consequent initiation of left-sided intracellular Ca2+-release induces downstream signaling events that break bilaterality. In this model, the flow of extra-embryonic fluid is not detected by cilia-based mechanosensation. B) In the two-cilia model, non-sensing motile cilia in the centre of the node create a leftward nodal flow that is mechanically sensed through passive bending of non-motile sensory cilia at the periphery of the node. Bending of the cilia on the left side leads to a left-sided release of Ca2+ that initiates establishment of body asymmetry. C) Schematic illustration of normal left-right body asymmetry (situs solitus) and five laterality defects that affect the lungs, heart, liver, stomach and spleen. Reprinted with permission from Fliegauf M, Benzing T, Omran H: When cilia go bad: Cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:880-893, 2007.

Different mechanisms lead to leftward flow, triggering calcium influx on the left side which in turn induces nodal growth differentiation factor (NODAL) expression.18 NODAL is a secretory protein that belongs to the transforming growth factor-β superfamily. Increasing NODAL levels on the left side induce paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 (PITX2) and left-right determination factor (LEFTY) gene expression. PITX2 is the master gene for establishment of left-sidedness and encodes a homeobox-containing transcription factor19, while LEFTY encodes secretory proteins that are closely related members of the TGF-β family capable of blocking NODAL signaling (by competitively interacting with a protein that serves as a coreceptor for NODAL [epidermal growth factor–Cripto-FRL1-Cryptic coreceptor] and one of its receptors [type II TGF-receptor chain]).20 This NODAL signaling block occurs predominantly in the midline and prevents passage of NODAL activity to the right side.

Disruptions in the process of left-right body axis determination can result in laterality disorders which can include a spectrum ranging from malpositioning to absence of internal organs (Figure 4C). Many of the involved signaling pathways belong to the TGF-β superfamily of proteins which includes bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), growth and differentiation factors (GDFs), NODAL, some of the wingless-type mouse mammary tumor virus integration site (Wnt) proteins and TGF-β (see Table 1 for all members).21 Proteins of the TGF-β superfamily are structurally related, interact with a specific set of cell surface receptors, and generate intracellular signals via signaling molecules of the Suppressor of Mothers Against Decapentaplegic (SMAD) family. Interaction of a ligand with its receptor triggers phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues of SMAD proteins. SMAD proteins belong to three distinct classes: receptor-regulated R-SMADs (SMAD1/2/3/5/8) act as phosphorylation targets. Co-SMADs (SMAD4) associate with R-SMADs in the nucleus and allow binding of the complex to DNA binding proteins which in turn alters gene expression. Inhibitory SMADs (SMAD6/7) counteract the effects of R-SMADs.21-23 Besides the SMAD-signaling pathway, there also exist a variety of non-SMAD signaling pathways that control cell adhesion, actin polymerization, microtubule stabilization and act on cytosolic proteins.23

Table 1.

Members of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily, divided into TGF-β like and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) like groups, with associated ligands, receptors and downstream signaling molecules (SMADs).23,115

| Group | Ligand | Type I receptor | Type II receptor | R-SMAD | Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β like group | TGF-β | Alk1 Alk2 Alk5 | TGF-β RII | SMAD2/3 SMAD1/5/8 | Control of cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis116 |

| Activin | Alk4 Alk2 | Act RII/IIB | SMAD2/3 SMAD1/5/8 | Controls morpho-genesis of branching organs, activation of fibroblasts, control of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis117 | |

| Nodal | Alk4 Alk7 | Act RII/IIB | SMAD2/3 | Left-right deter-mination, mesoderm/ endoderm development117 | |

| GDF | Alk4 Alk5 Alk6 | Act RIIB | SMAD2/3 SMAD1/5/8 | Mesoderm induction, left-right deter-mination118 | |

| BMP like group | BMP | Alk1 Alk2 Alk3 Alk6 | BMP RII/IIB | SMAD1/5/8 | Control of cell growth, proliferation, differ-entiation, apoptosis118 |

| BMP | Alk2 Alk4 Alk5 Alk7 | Act RII/IIB | SMAD1/5/8 SMAD2/3 | ||

| GDF | Alk5 Alk6 | BMP RII | SMAD2/3 SMAD1/5/8 | Mesoderm induction, left-right deter-mination118 | |

| MIS | Alk2 Alk3 Alk6 | MIS RII | SMAD1/5/8 | Sex differentiation, control of cell apoptosis119 |

Abbreviations: TGF-β= Transforming growth factor-β; BMP= Bone morphogenetic protein; GDF= Growth differentiation factor; MIS= Mullerian inhibiting substance; Alk= Activin receptor-like kinase; TGF-β RII= Transforming growth factor-β receptor 2; Act RII/IIB= Activin receptor type-2A/2B; BMP RII/IIB= BMP type II receptor; MIS RII= Mullerian inhibiting substance type 2 receptor; SMAD= SMAD family member.

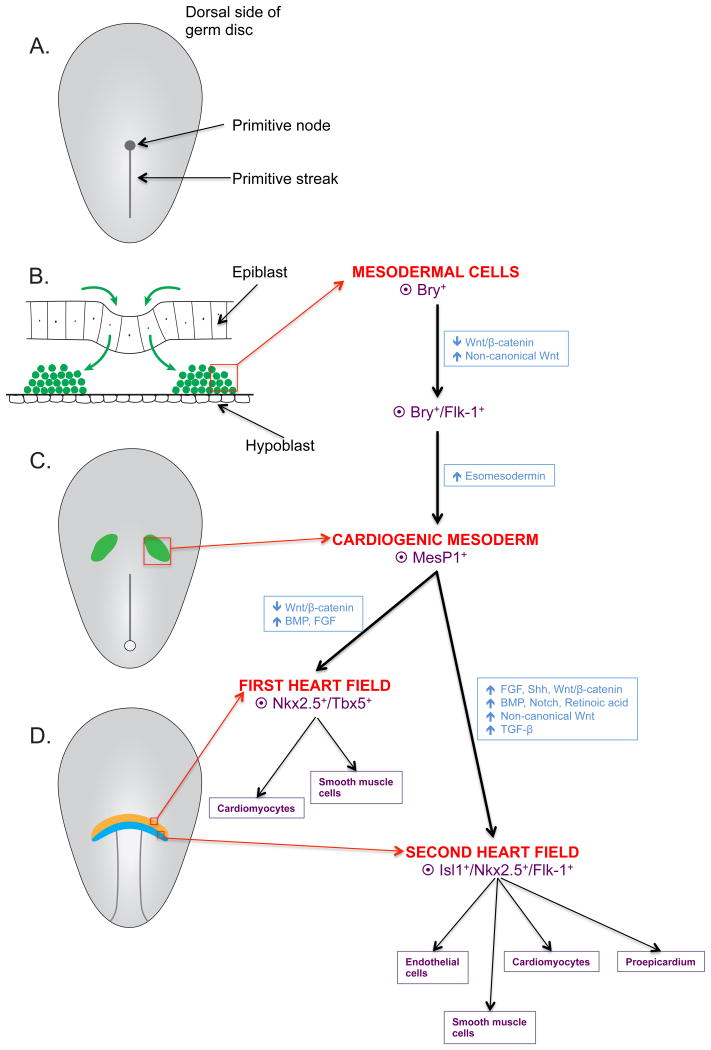

Figure 5 summarizes the required steps for the formation of cardiac progenitor cells. In Figure 5A, a presomite embryo at day 16 with the primitive streak and primitive node is shown. In a cross-section of the cranial part of the embryo, as shown in Figure 5B, epiblast cells invaginate through the primitive streak. During this transition, signaling pathways including BMP, NODAL, Wnt/β-catenin and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) trigger mesodermal induction causing the epiblast cells to differentiate into mesodermal cells. Those mesodermal cells, characterized by expression of the T-box transcription factor Brachyury/T (Bry)24, migrate to the lateral splanchnic mesoderm where they undergo differentiation into cardiogenic mesoderm (Figure 5C). The first differentiation step includes downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and upregulation of noncanonical Wnt signaling, resulting in expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2, Flk-1) that serves as a marker for cells committed to cardiogenic fate. For the second step, esomesodermin (T-box transcription factor) signaling induces the expression of the mesoderm posterior 1 (MESP1) gene yielding the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor MESP1, a core factor involved in programing cells towards cardiogenic fate.25 Cardiogenic mesoderm then further differentiates into first and second heart field cells (Figure 5D). Differentiation into first heart field cells is induced via upregulation of BMP and FGF signaling and downregulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, resulting in expression of NKX2.5 and TBX5. Upregulation of BMP, NOTCH and noncanonical Wnt signaling causes differentiation into second heart field cells with expression of insulin gene enhancer protein (Isl1), NKX2.5 and Flk1.26

Figure 5.

Overview of the step-wise formation of cardiac progenitor cells: origination from epiblast cells and subsequent differentiation to mesodermal cells and first/ second heart field cells. A) Presomite embryo at day 16 with primitive streak and primitive node. B) Cross-section through the cranial part of the embryo showing the epi- and hypoblast cells. The primitive streak is shown as an invagination through which epiblast cells migrate. During this process, the epiblast cells differentiate into mesodermal cells characterized by expression of the T-box transcription factor Brachyury/T (Bry+). C) Mesodermal cells migrate to the lateral splanchnic mesoderm and undergo further differentiation to cardiogenic mesoderm with expression of mesoderm posterior 1 (MesP1), a core factor involved in committing cells to their cardiogenic fate. D) Cardiogenic mesoderm further differentiates into the first and second heart field, characterized by the expression of NK2 Homeobox 5 (NKX2.5), T-Box protein 5 (TBX5) and insulin gene enhancer protein (Isl1), NK2 Homeobox 5 (NKX2.5) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (Flk-1), respectively.

Cardiac Progenitor Cells

The fertilized ovum is an uncommitted cell (i.e., cell fate not determined) that differentiates into numerous committed cell lines with limited opportunity to be reprogrammed. How does a specific cell know its fate? At least one component is the chemical signals provided by other nearby cells. No one signal is deterministic; rather, it seems that combination of signals determine cell fate. Similarly, migration of cells in a particular direction seems to be controlled by multiple factors. Part of this process appears to be determined by chemical signals (chemotaxis) from nearby or distant cells while mechanical signals (mechanotaxis) from neighboring cells also play a role.27 Our knowledge of both of these processes is incomplete.

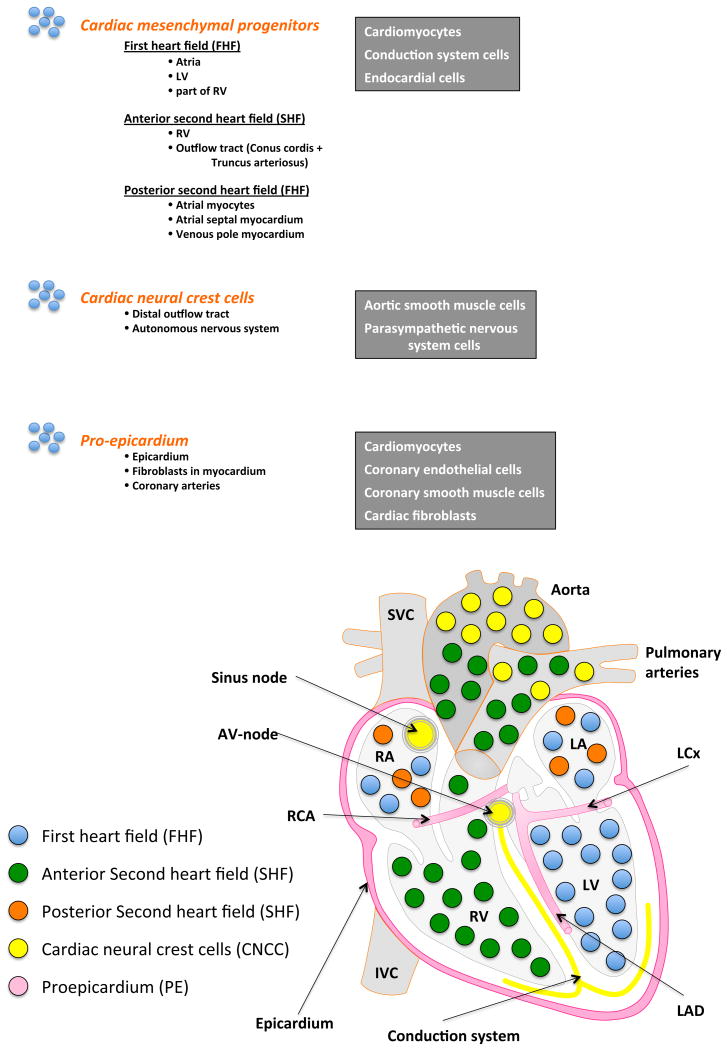

The developing and adult heart is composed of several cell populations including myocytes, fibroblasts, epicardium, specialized cells of the conduction system, endocardial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells (Figure 6). Cells that form the heart are derived from three distinct precursor populations26: cardiac neural crest cells, cardiogenic mesoderm cells, and proepicardium cells. Cardiac neural crest cells originate from the neuroectoderm, while the latter two precursor populations are of mesodermal origin.

Figure 6.

Three cardiac progenitor cell populations are listed with their final contributions to the mature human heart. The lower diagram depicts the spatial locations of the cardiac progenitor cell populations.

Cardiogenic mesodermal cells

Cardiac progenitor cells are derived from the intraembryonic mesoderm and arise from the cranial third of the primitive streak during early gastrulation. The cellular fate of these cardiac mesodermal cells is uncommitted but after migration they become specified to differentiate into hemangioblasts (erythroid and vascular precusors) and cardiogenic mesoderm of the first and second heart fields. These mesodermal cells leave the primitive streak and migrate in a cranial-lateral direction to become localized on either side of the primitive streak forming the cardiac crescent which consists of first heart field cells laterally and second heart field cells medially.26 The cells of the first heart field and second heart field proliferate and migrate as cohorts to form different structures of the heart. The heart tube is formed from cells from the first heart field through fusion in the midline after lateral folding of the embryonic disc. This leads to he formation of the early left ventricle and parts of the atria and right ventricle.

Proliferation and migration of cardiac precursor cells from the second heart field to the cranial and caudal pole contribute to the growth of the heart tube.7,10 The second heart field is composed of progenitor cells from the medial splanchnic mesoderm adjacent to the pharyngeal endoderm and is the source of the outflow tract (conus cordis and truncus arteriosus) as well as the majority of the right ventricle and atria/ venous pole of the heart.9,10 The second heart field forms the endothelium, the inner sheath of the cardiac tube and compartments of the heart as they develop. It plays a critical role in trabeculation of chamber myocardium and in valve formation, initiated by delamination of endocardial cells to form the cushions28.

Proepicardium

A subset of cardiogenic caudal dorsal mesoderm of the second heart field differentiates into proepicardial cells.26 These precursor cells predominantly migrate towards the heart tube and envelop it to become epicardium. Another subset undergoes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation and form interstitial fibroblasts and coronary blood vessels including vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelium.7 A few of the proepicardial cell precursors differentiate into myocytes located in the muscular ventricular septum and atria.5,26

Cardiac neural crest cells

Cardiac neural crest cells arise from the dorsal neural tube and migrate through the posterior pharyngeal arches into anterior domain of the second heart field before entering the anterior part of the heart tube. They are involved in formation of the outflow tracts of the heart including their valves, the myocardium from the aorta and pulmonary artery, aortic arch arteries, septation, cardiac autonomic nervous system and venous pole. While cardiac neural crest cells differentiate into aortic smooth muscle and autonomic nervous system cells, their only active structural contribution includes cells of the aorticopulmonary septum, endocardial cushions and parasympathetic nervous system of the heart.29,30 In contrast, their role in formation of the other aforementioned structures lies mainly in the provision of cell signals.26

Etiology of Errors in Cardiac Development

Tracing congenital heart disease to its precise etiology is difficult. While genetics provides a sound rationale for linking a specific mutation within a gene responsible for cardiac development to an expressed malformation, less than 20% of congenital heart disease can be explained by either chromosomal defects or single-gene disorders.31,32 Genetic predisposition for congenital heart disease presents on a continuous spectrum from syndromic congenital heart disease (large genetic disruptions leading to alterations in many genes with resultant cardiac defects and extracardiac manifestations) to isolated congenital heart disease (small genetic disruption affecting a single gene responsible for cardiac development, resulting in an isolated cardiac defect).33

In simple terms, there are three ways of disrupting normal heart development. Two of them are genetic in nature. That is, congenital heart disease can occur by either inheriting a gene mutation from a parent or by acquiring a de novo somatic gene mutation during embryogenesis. The third reason for disruption of normal heart development is primarily non-genetic and includes a variety of precipitating events such as infections, maternal exposure to alcohol, some prescription drugs, environmental teratogens, and metabolic disturbances.34 The latter can be influenced by genetic and non-genetic mechanisms.

Genetic alterations also come in different varieties. Conditions defined by chromosomal aneuploidy such as Down syndrome (Trisomy 21), Edwards syndrome (Trisomy 18), Turner syndrome (Monosomy X) and Patau syndrome (Trisomy 13) result in an increase or decrease in the number of copies of a gene. Copy number variants are caused by deletions and duplications and usually involve more than 1000 base pairs. Finally, mutations can cause defects in single genes as seen in Noonan syndrome or Alagille syndrome.

Recent studies increasingly recognize another factor that can contribute to congenital heart disease: epigenetics. Epigenetics describes changes in the transcriptional potential of cells that are not directly caused by alterations in the DNA itself. For example, proteins that modify histones (alkaline proteins that bind to DNA and organize the DNA-histone complex into nucleosomes) alter the transcriptional propensities of certain DNA sequences and thereby increase or decrease the expression of genes.35 Along those lines, genomic imprinting, an epigenetic phenomenon that describes the variability in expression of a gene dependent of the parent of origin (e.g. an imprinted allele inherited from the father is silenced and only the allele inherited from the mother is expressed) is presumed to be another etiologic contributor to congenital heart disease.36,37

Description of specific congenital heart defects

In this section, we will try to link the cellular and molecular mechanisms to the final macroscopic expression of specific congenital heart defects. Recall that the majority of congenital heart defects have heterogeneous pathophysiologic mechanisms, and as our knowledge of molecular biology and genetics expands, new pieces of the puzzle are constantly added.

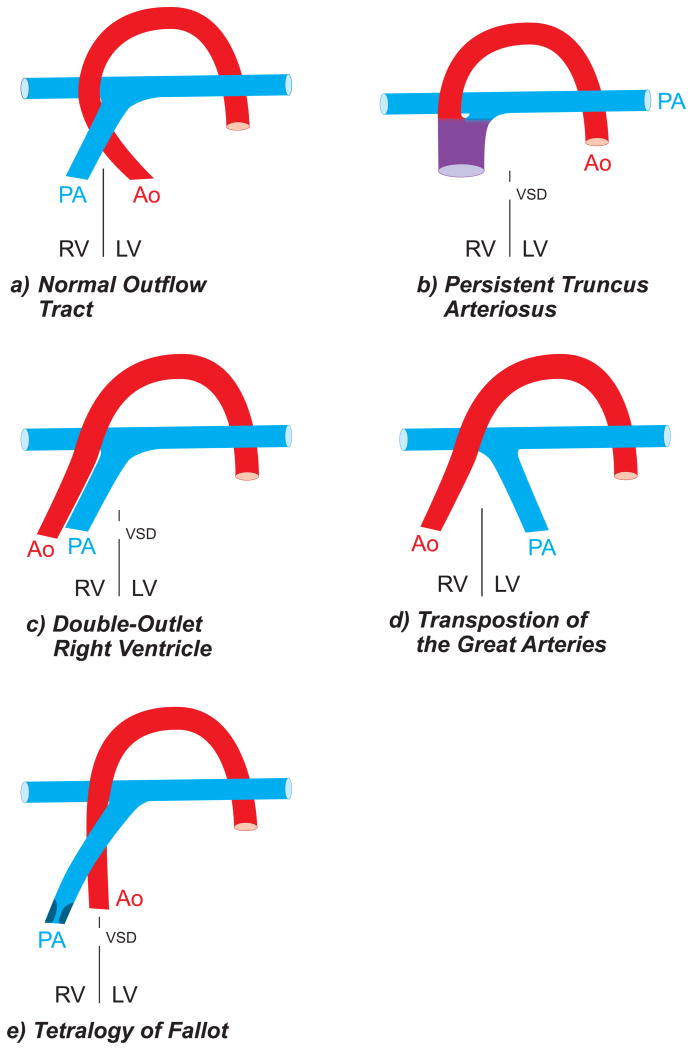

In the first part of this section, we chose two conditions (atrial septal defects, heterotaxy) and a group of congenital heart defects that share a similar pathogenesis (cardiac outflow tract anomalies including persistent truncus arteriosus, double-outlet right ventricle, transposition of the great arteries and tetralogy of Fallot) to provide a conceptual framework. In the second part, we describe additional congenital heart defects, although in a more succinct manner.

The basic tenet of molecular cell biology is the step-wise progression from a gene (located on the DNA) to RNA (transcribed from the gene) to a protein (Figure 2a). A layer of complexity is added by various modifications that can occur along this process as detailed in Figure 2b.

Atrial septal defects

An atrial septal defect is the third most common congenital heart defect. Based on the location of the defect in the atrial septum, atrial septal defects can be divided into patent foramen ovale, ostium primum defect, ostium secundum defect, sinus venosus defect, coronary sinus defect, and common atrium.38 Atrial septal defects can be observed in aneuploidy syndromes (Pateau, Edwards), abnormal chromosomal structure syndromes (del22q11), single gene mutations syndromes (Noonan), non-syndromic congenital heart disease with copy number variations and single gene mutations causing isolated congenital heart disease (GATA4, GATA6, ACTC1).

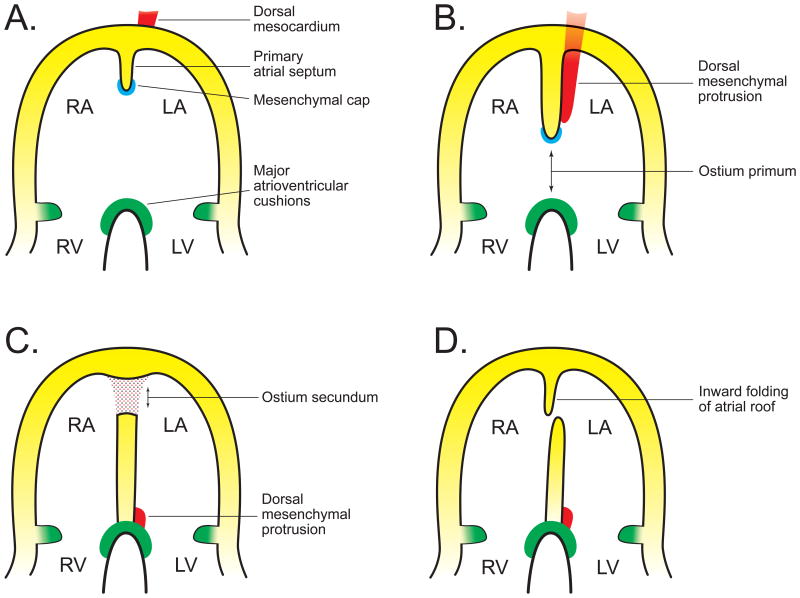

Four main structures form the atrial septum: the superior and inferior atrioventricular cushions, the primary atrial septum with its mesenchymal cap and the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (Figure 7).12,39 Both atrioventricular cushions and the mesenchymal cap are derived from endocardium that undergoes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation, while the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion arises from the second heart field. The process begins with fusion of the superior and inferior atrioventricular cushions at the level of the atrioventricular canal. A primary atrial septum arises from the atrial roof and grows towards the atrioventricular cushions, partitioning the common atrium into a left and right chamber. The leading part of the primary atrial septum carries a mesenchymal cap. The dorsal mesenchymal protrusion is associated with the mesenchymal cap and accompanies its growth downward towards the atrioventricular cushions. The dorsal mesenchymal protrusion is derived from the dorsal mesocardium that suspends the heart in the pericardial cavity. After breakdown of its central portion, the part suspending the atrial pole proliferates and penetrates through the atrial wall to give rise to the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion.40 After the primary atrial septum reaches close proximity to the atrioventricular cushion, the small opening between the primary atrial septum and the atrioventricular cushions is called ostium primum. It is closed by fusion of the mesenchymal cap with the atrioventricular cushions (anteriorly) and the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (posteriorly). During closure of the ostium primum, part of the primary atrial septum at the atrial roof dissolves to create a small opening, the ostium secundum. Inward folding of the atrial roof which gives rise to the secondary atrial septum later closes the ostium secundum.12,41,42

Figure 7.

Overview of processes leading to atrial septation. A) Atrial septation begins with formation of the primary atrial septum (septum primum) that extends from the atrial roof downwards towards the major atrioventricular cushions. The leading edge of the primary atrial septum carries a mesenchymal cap. The venous pole of the heart is attached to dorsal mesocardium. B) As the primary atrial septum continues its migration downwards and approaches the major atrioventricular cushions, it closes a gap known as ostium primum. Mesenchmal cells from the dorsal mesocardium have invaded the common atrium and join the downward growing primary atrial septum as the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion. C) After fusion of the primary atrial septum, mesenchymal cap and dorsal mesenchymal protrusion with the major atrioventricular cushions, the ostium primum is closed. At the same time, part of the cranial septum primum breaks down and forms the ostium secundum. D) Inward folding of the myocardium from the atrial roof produces the secondary atrial septum (septum secundum) which grows downwards to occlude the ostium primum by mechanism of a flap-valve (at birth, pulmonary vasculature dilates leading to a drop in right atrial pressure; the higher left atrial pressure pushes the primary atrial septum against the secondary atrial septum).

Atrial septation defects arise from a different pathway than the above. The endocardial cushion rests on myocardial cells. Those myocardial cells differ from regular chamber myocardium in their gene expression patterns. Their programing is dependent on TBX2, BMP2 and nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 2/3/4 (NFATC2/3/4) proteins which act to suppress chamber-specific genes and induce secretion of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation -regulating molecules. Those molecules are secreted into the neighboring endocardial cushion where they meet endocardial cells with another specific set of gene expression including the following receptors: ALK2/3/5, VEGFR, NOTCH1 and β-catenin. Induced by the secreted molecules from the myocardium, the endocardial cells undergo endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation and form the superior and inferior atrioventricular cushion as well as the mesenchymal cap on the primary atrial septum.12 The dorsal mesenchymal protrusion is formed by the secondary heart field. Recently, defects in its formation have been implicated in atrioventricular canal defects and ostium primum atrial septal defects.43,44 Briggs et al.45 showed that deletion of the BMP-receptor (ALK3) in the secondary heart field resulted in hypoplasia of the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion leading to impaired secondary heart field cell expansion and subsequent development of an ostium primum defect. Besides impaired cell expansion, aberrant apoptosis of secondary heart field cells in the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion as well as impaired cell migration can contribute to septation defects.46

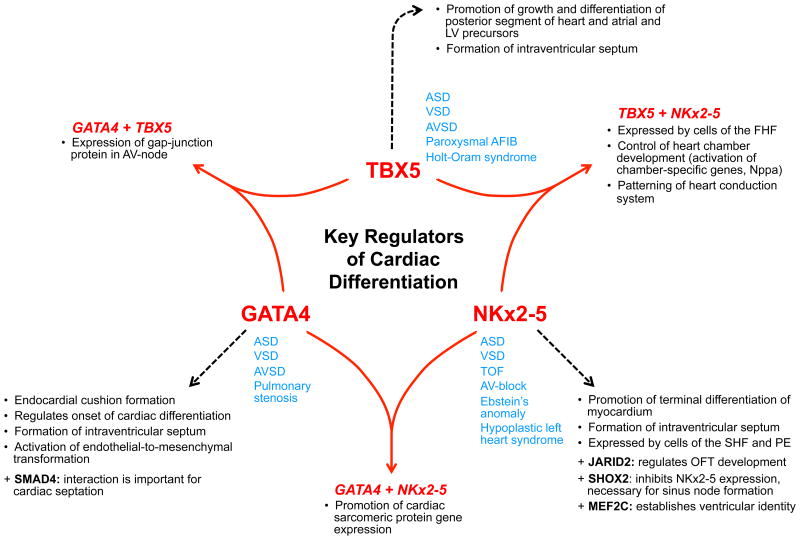

Certain genes encode proteins that function as transcription factors, for example TBX5, TBX20 (both T-box transcription factors), GATA4 (a zinc finger transcription factor) and NKX2.5. Transcription factors bind to specific DNA sequences and influence the transcription rate of the associated gene. In some instances, a transcription factor can perform this role alone, but more frequently it forms a complex with other proteins. For example, the interaction between GATA4 and TBX5 leads to activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), a member of the cyclin-dependent kinase family that is involved in cell-cycle regulation.47 TBX5 alone is able to activate CDK247 and CDK6.44 TBX5 expression has been demonstrated in the posterior second heart field and is critical for the development of the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion, a second heart field derived tissue. Both structures are involved in cardiac septation. Mutations in TBX5, TBX20, GATA4 and NKX2.5 have been associated with atrial septal defects.48 Another set of genes encodes structural proteins. In the heart, cardiomyocytes express sarcomeric filaments that allow generation of tension resulting in a heartbeat that propels blood. Mutations in α-actin gene (ACTC1) or myosin heavy chain genes (MYH6, MYH7) can lead to atrial septal defects.

The involvement of TBX5, GATA4 and NKX2.5 in a variety of processes has established their function as key regulators of cardiac differentiation. Figure 8 gives a condensed overview of their interaction, function and cross-talk. However, a clear relationship between a mutation in TBX5 leading to an atrial septal defect in every case cannot be established. Along this line, the question arises why certain individuals with a set of mutations including TBX5 develop an atrial septal defect while others with similar mutations develop a ventricular septal defect. Two concepts may provide an explanation for this observation: complex inheritance and transcriptional/ translational network interaction. From a genetic standpoint, complex inheritance includes the terms heterogeneity, variable expressivity and reduced penetrance. Heterogeneity is based on the observation that a certain phenotype can be determined not only by one gene but by the interaction of multiple genes. Variable expressivity describes the state in which two individuals inherit the same disease allele but may express different phenotypes (for example, one individual develops an atrial septal defect while the second individual develops a ventricular septal defect). Lastly, reduced penetrance describes the observation that two individuals may have inherited the disease allele, but only one individual develops the disease, i.e. expresses the phenotype.49

Figure 8.

Condensed overview of the function and interaction between three major transcription factors that are viewed as key regulators of cardiac differentiation: T-Box protein 5 (TBX5), GATA-binding protein 4 (GATA4) and NK2 Homeobox 5 (NKX2.5).

Complex transcriptional/ translational network interactions are in a way similar to heterogeneity. They describe the phenomenon that cardiac morphogenesis is controlled by a complex network of genes and transcription factors that are subject to constant modification, cross-talk and redundancies as well as environmental influences.31,50

Heterotaxy

Heterotaxy describes disorders of defective left-right axis determination resulting in atypical positioning of internal organs. It is important to understand that heterotaxy is part of a spectrum of laterality defects.

The literal translation of the greek word heterotaxy (composed of “hetero”, meaning “different,” and “taxy”, meaning “arrangement”) is “abnormal arrangement of bodily parts”. Along those lines, the Nomenclature working group of the International Society for Nomenclature of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease51, defined heterotaxy as “[…] an abnormality where the internal thoraco-abdominal organs demonstrate abnormal arrangement across the left-right axis of the body”. The expected normal arrangement of internal organs along the left-right axis is known as situs solitus. Unfortunately, the working group's exclusion of situs inversus (complete mirror-imaged arrangement of internal organs along the left-right axis) from the heterotaxy spectrum may add some confusion. Situs ambiguus describes a state in which organ arrangements as described in situs solitus and situs inversus are found in the same individual, that is, thoracic and abdominal organ positioning does not show a clear lateralization. Impairment of left-right axis formation occurs early in embryonic development (starting at the third week) and is dependent on the establishment of an organizer region, a function provided by the primitive node (see Cell Signaling in Embryogenesis). Based on the unique arrangement of thoracic and visceral organs in the adult organism, it is conceivable that defects in left-right axis formation will impact not only the heart but also other internal organs.

Multiple descriptions and characterizations of patients with heterotaxy have been proposed over the years that can become a source of confusion for the clinician not intimately familiar with this condition. A commonly cited description uses splenic anatomy which yields the designations “right isomerism, bilateral right-sidedness and asplenia syndrome” and “left isomerism, bilateral left-sidedness and polysplenia syndrome”. Right isomerism includes absence of a spleen (asplenia), bilateral trilobed lungs and cardiovascular abnormalities. Left isomerism is characterized by presence of multiple spleens (polysplenia), bilateral bilobed lungs and cardiovascular abnormalities (Figure 4C).18,52 A more contemporary approach advocates segregation of heterotaxy patients by morphology of the atrial appendages, as isomerism in the heart is predominantly restricted to the atria.53,54 Determination of atrial isomerism primes the evaluator to seek specific intracardiac abnormalities, such as univentricular atrioventricular connections, absence of the coronary sinus, pulmonary atresia/ stenosis and totally anomalous pulmonary connection which are frequently associated with isomeric right atrial appendages, while interruption of the inferior caval vein and aortic coarctation are more frequently encountered in individuals with isomeric left atrial appendages.53 Determination of atrial isomerism can be determined clinically with computed tomography angiography55 or echocardiography.56 Loomba et al.57 recently reported on the impact of isomerism on survival in heterotaxy and found that right isomerism was associated with decreased survival from birth to age 16 years compared to left isomerism; biventricular repair was associated with superior survival in comparison to univentricular repair.57 The latter finding is important insofar as right isomerism often presents with complex cardiac malformations requiring univentricular repair while left isomerism is associated with less complex cardiac malformations that often can be addressed with biventricular repair.

Individuals diagnosed with heterotaxy can have a variety of organ abnormalities that may involve the gastrointestinal tract (intestinal malrotation, biliary atresia, annular pancreas, anal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula), respiratory tract (bronchiectasis, ciliary dysfunction, bilateral right- or left-sided lungs), genitourinary tract (horseshoe kidney, hypoplastic/ dysplastic/ absent kidney, ureteral abnormalities, cryptorchidism), central nervous system (hydrocephalus, absent corpus callosum, holoprosencephaly, meningomyelocele), immunologic system (splenic hypofunction despite polysplenia, increased susceptibility to infections) and vascular system (extra hepatic portocaval communications, interrupted inferior vena cava with azygous or hemiazygous continuation).58,59

The heart, being one of the most important asymmetric organs, can be significantly affected, resulting in complex congenital heart disease presentations including single ventricle, pulmonary stenosis, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, transposition of great arteries, tetralogy of Fallot, double outlet right ventricle, double inlet left ventricle, atrioventricular septal defects, total/ partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection, aortic coarctation, atrial isomerism, bilateral/ hypoplastic/ absent sinus node(s), single coronary artery, interrupted inferior vena cava and bilateral superior vena cava.18,60,61 Patients with heterotaxy are prone to arrhythmias. The presence of two atrioventricular conducting pathways when there are duplicated atrioventricular nodes increases susceptibility for supraventricular reentrant tachycardias while the lack of a normally situated sinus node can predispose patients to development of atrioventricular conduction blocks. Loomba et al.62 investigated the occurrence of chronic cardiac arrhythmias in heterotaxy patients. Comparing left and right isomerism, the authors found no significant differences in cardiac malformations and sinus node position. In patients with left isomerism, the atrioventricular node was more frequently positioned posteriorly (86% vs. 18%). Patients with right isomerism more frequently had duplicated atrioventricular nodes (82% vs. 14%). Tachycardias were more frequently encountered in patients with left isomerism (atrial flutter, atrial tachycardia, junctional tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia), while patients with right isomerism showed frequent conduction blocks (first/second-degree atrioventricular block, complete atrioventricular block, intraventricular conduction delay, sick sinus syndrome).

A recent descriptive epidemiologic study conducted by Lin et al.63 shed some light on the prevalence of heterotaxy. By querying the National Birth Defects Prevention Study database in the time frame of 1998 to 2007, the authors identified 517 cases with nonsyndromic laterality defects. Those cases included 378 cases with heterotaxy and 139 cases with situs inversus totalis, yielding an estimated birth prevalence of 0.81 per 10,000 live births. In regards to distribution of congenital heart disease amongst individuals with heterotaxy, the study reported simple congenital heart disease (atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, mild pulmonary valve stenosis, mild aortic stenosis) in 9.3%, complex congenital heart disease in 67.7% and no congenital heart disease in 23.0%. The most frequent cardiac malformation was a complete atrioventricular canal defect (48.4%), followed by conotruncal defects (truncus arteriosus, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of great arteries, double outlet right ventricle [47.4%]) and interrupted inferior vena cava as well as right-sided defects (Ebstein anomaly, pulmonary stenosis, pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum, non-tetralogy of Fallot pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect) in 40.5% of cases.63

Few cases of heterotaxy can be traced to a monogenic etiology. These include autosomal dominant heterotaxy64-67, X-linked heterotaxy68-70 and autosomal recessive heterotaxy in form of Kartagener syndrome (primary ciliary dyskinesia).71-73 Genes associated with heterotaxy include ZIC3, CRYPTIC, NODAL, CFC1, ACVR2B, LEFTY2, CITED2, and GDF1.18,52 The majority of cases can be caused by a variety of disruptions in the left-right axis patterning process.

Cardiac outflow tract anomalies

Cardiac outflow tract anomalies represent a spectrum of heart development disorders that share etiological features. Cardiac neural crest cells are instrumental in shaping the outflow tract by controlling its remodeling process. Disruption of neural crest cell induction, specification, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation, migration, cell-cell interaction, and condensation to form the outflow tract are thought to explain the major factor in the genesis of conditions such as persistent truncus arteriosus, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great arteries and double-outlet right ventricle.74,75 Recall that the outflow tract is initially populated by resident first heart field cells which are joined by migratory second heart field cells. Later, cardiac neural crest cells begin migrating from the dorsal neural tube into the outflow tract where they are involved in formation of the aorticopulmonary septum by contributing cells for the outflow tract structure and shape. They also influence neighboring cells, specifically cells of the second heart field, by modulating secreted signaling factors such as FGF.76 Furthermore, cardiac neural crest cells contribute to the endocardial cushion mass which is formed by endothelial cells that undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation. Defects in cardiac neural crest cells can occur at multiple levels. As a result, many of the different cardiac outflow tract malformation phenotypes can be traced back to cardiac neural crest cells, but the presence of multiple other cell types adds a layer of complexity and often precludes identification of a “single defect”. Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome serves as an interesting example for cardiac outflow tract anomalies.77 It is associated with a variety of cardiac outflow tract anomalies such as tetralogy of Fallot (most common cyanotic congenital heart disease), truncus arteriosus, double-outlet right ventricle, transposition of the great arteries, coarctation of the aorta and interrupted aortic arch. The commonly deleted region on chromosome 22q11.2 harbors more than 35 genes, including TBX1, ERK2 (alias for mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK1]) and CRKL. TBX1 is required for growth and septation of the conotruncus78 while developing neural crest cells require ERK2 signaling to be able to aid in conotruncal development.79 The role of CRKL, a member of the adaptor protein family that participates in multiple signaling pathways (including the MAP-kinase pathway) is less defined.

Persistent truncus arteriosus

Persistent truncus arteriosus describes the failure of septum formation that divides the truncus arteriosus into aorta and pulmonary artery, leaving only one combined outflow tract for the blood that is ejected by each ventricle (Figure 9B). Mixing of blood occurs via a ventricular septal defect. The combined outflow tract can be positioned either above the right or left ventricle, or can override the ventricular septal defect. Persistent truncus arteriosus is associated with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and TBX1 deficiency caused by point mutations.

Figure 9.

A) Configuration of the outflow tract in a normally developed heart; B) Persistent truncus arteriosus in which aorta (Ao) and pulmonary artery (PA) share a common outflow tract with a single “truncal” valve; C) Double-outlet right ventricle in which both the aorta and pulmonary artery arise from the right ventricle; D) d-Transposition of the great arteries in which the aorta arises from the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery arises from the left ventricle; E) Tetralogy of Fallot in which the pulmonary artery arises from the right ventricle but includes a right ventricular outflow tract obstruction at the infundibular, valvar or supravalvar level. The aorta is overriding the ventricular septum that includes a septal defect (VSD). Adapted in modified form from Neeb Z, Lajiness JD, Bolanis E, Conway SJ: Cardiac outflow tract anomalies. WIREs Dev Biol 2:499-530, 2013.

Double-outlet right ventricle

During development of the outflow tract, malalignment defects trigger the development of a double-outlet right ventricle. The aorticopulmonary septum forms normally within the truncus arteriosus and separates the great vessels (aorta and pulmonary artery), but incorrect alignment of the aorta over the right ventricle leads to the final position in which both great vessels arise from the right ventricle (Figure 9C). This defect is frequently associated with a ventricular septal defect and pulmonary stenosis, causing cyanosis due to a significant right-to-left shunt after birth. Obler et al.80 analyzed the underlying genetic make-up in 149 individuals diagnosed with double-outlet right ventricle. The majority of cases (56%) were found to have a non-chromosomal disorder and but the condition often occurred in conjunction with several syndromes that included Adams–Oliver, Ellis–van Creveld, Gardner–Silengo–Wachtel, Kabuki, Kalmann, Melnick–Needles, Noonan, Opitz, Ritscher–Schinzel, and Robinow syndromes. A specific gene mutation was only identified in very few cases (10/149). Eight individuals showed a disrupted CFC1 gene (encoding extracellular signaling proteins involved in development of lateral plate mesoderm), whereas two individuals had a mutation in the CSX gene (encoding the transcription factor NKX2.5). A smaller subset of cases (41%) had associated chromosomal abnormalities, mainly Trisomy 18 and 13.80

Transposition of great arteries

D-transposition of the great arteries, which stands for “dextro-loop transposition” describes the relationship of the ventricles to the atria after cardiac looping to the right (Figure 9D). In d-transposition of the great arteries, there are concordant atrioventricular and discordant ventriculoarterial connections: the morphologic left ventricle is connected to the pulmonary artery, while the right ventricle connects to the ascending aorta. This creates two parallel circulations: blood is pumped from the right ventricle into the systemic circulation (aorta) and returns back to the right ventricle via the right atrium. The left ventricle ejects blood into the pulmonary circulation (pulmonary artery) which returns to the left ventricle via the left atrium. In contrast, congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries must be strictly separated from d-transposition of the great arteries due to its different pathophysiology and pathogenesis. Congenitally corrected transposition arises due to dysfunctional cardiac looping to the left instead of the right side. The most common manifestation (94%) of this physiology occurs in patients with [S,L,L] segmental anatomy. That is, there is atrial situs solitus, L-loop ventricles, and L-loop great arteries. A right sided right atrium connects via a right sided mitral valve and left ventricle to a right sided and posterior pulmonary artery. A left sided left atrium connects via a left sided tricuspid valve and right ventricle to a left sided and anterior aorta.

Transposition of the great arteries is a complex lesion and an understanding of its pathogenesis is incomplete. Two theories have been formulated. Goor and Edwards proposed that a defect in the infundibular rotation causes transposition of the great arteries by preventing the clockwise rotation of the aorta towards the left ventricle.81 De la Cruz hypothesizes that instead of the normal, spiral-like movement of the aorto-pulmonary septum, it develops in a linear fashion in patients with transposition of the great arteries, thereby connecting the aortic arch to the anterior conus on the right ventricle.82,83 Heterotaxy is the only genetic syndrome with which transposition of the great arteries is strongly associated. This explains the association with genes involved in establishment of laterality such as ZIC3, CFC1 and NODAL.84

Tetralogy of Fallot

With an incidence of ∼0.3%, tetralogy of Fallot is the most common form of cyanotic congenital heart diseases. The four distinguishing features include ventricular septal defect, overriding of the aorta, right ventricular outflow obstruction and right ventricular hypertrophy (Figure 9E).85 Tetralogy of Fallot is associated with syndromes sharing a deletion of chromosome 22q11 (DiGeorge syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome). More commonly, it occurs sporadically but its genetic etiology is poorly understood. Tetralogy of Fallot has been associated with rare copy number variations of TBX186, SNX8 87, PLXNA2 88, NOTCH1 and JAG1.89

Bicuspid aortic valve

The incidence of bicuspid aortic valve disease varies between studies but is commonly quoted to be 0.4%-2.25%.1 It is an important anatomic entity as its presence increases the risk for development of aortic valve stenosis, regurgitation, or infective endocarditis as well as ascending aorta aneurysm and/or dissection.90-92 Bicuspid aortic valve disease can arise as a new mutation or can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion; unfortunately, it shows considerable heterogeneity and neither the genetic basis nor the phenotypic expression can always be attributed to a simple a single gene defect.

The presence of bicuspid aortic valve disease in combination with genetic syndromes mostly affects females such as those with Turner syndrome (Monosomy X), DiGeorge syndrome (del 22q11.2), Loeys-Dietz syndrome (TGFBR1/2), Andersen-Tawil syndrome (KCNJ2), Larsen syndrome (FLNB), Kabuki syndrome (KMT2D, KDM6A) and familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissection [TAAD](ACTA2).93 Bicuspid aortic valve disease can result from familial inheritance, although, with the exception of NOTCH1, in a very small proportion of familial cases as no single trigger gene has so far been implicated.94,95 Linkage analysis has identified multiple genes including TGFBR2, TGFBR1, NOTCH1, ACTA2, KCNJ293, MYH11, GATA5, FLNA and SMAD396 that are associated with aortic valve development.

It is clear that the majority of non-syndromic related cases of bicuspid aortic valve disease are not due to a single genetic variant. More likely, its inheritance results from a combination of numerous rare or uncommon genetic variants including copy number variants, epigenetic modifications and environmental causes.92 Because most animal models of bicuspid aortic valve disease are created from NOTCH1 and GATA5/6 genes; both proteins seen in the developing heart, it is likely that many variants in a single pathway are responsible for an overall likelihood of developing a bicuspid aortic valve.

Mitral valve prolapse

Mitral valve prolapse is a common disorder that affects 2-3% of the population. It is caused by fibromyxomatous degeneration resulting in thickening and lengthening of the mitral valve leaflets. This, in turn, leads to displacement of one or both leaflets into the left atrium past the mitral annulus during systole with associated poor coaptation. The genetic basis of syndromic mitral valve prolapse has been traced to TGF-β signaling.97,98 The final common pathway of TGF-β signaling dysregulation leads to differentiation of valvular interstitial cells to myofibroblasts with subsequent extracellular matrix production and deposition resulting in myxomatous degenerations and altered mitral valve architecture.99 Mitral valve prolapse is strongly associated with Marfan syndrome caused by mutations in Fibrillin 1 (FBN1). FBN1 usually inhibits TGF-β signaling; loss-of-function mutations therefore lead to an increase in active TGF-β, increased matrix deposition and thickened valve leaflets. Loeys-Dietz syndrome, another syndrome with strong association to mitral valve prolapse, is caused by mutations in TGFBR1 and TGFBR2. A non-syndromic cause of mitral valve prolapse has been identified in mutations of the Filamin A gene (FLNA), which also affects TGF-β signaling.13

Ebstein anomaly of the tricuspid valve

Ebstein anomaly is a rare congenital heart defect that involves the right ventricle, right atrium and tricuspid valve. During normal development, the superficial layer of the right myocardium delaminates to form the septal and posterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve. Failure of delamination results in adherence of the leaflets to the ventricular myocardium causing apical displacement of the tricuspid valve leaflet hinge points with normal position of the tricuspid valve orifice. The area of the right ventricle between the tricuspid valve orifice and the resultant apically displaced tricuspid leaflet hinge points becomes atrialized and varying degrees of tricuspid valve insufficiency ensue.100,101 Ebstein anomaly is associated with atrial tachyarrhythmias including atrial fibrillation and flutter as well as accessory conduction pathways such as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.102,103 While the genetic basis for this condition is largely unknown, recent investigations have identified an association of familial Ebstein anomaly with mutations in MYH7, a sarcomere gene encoding the cardiac beta-myosin heavy chain.104,105 It is not clear why a sarcomeric protein is responsible for Ebstein anomaly, but a reasonable working hypothesis is that embryonic cell migration may be impaired by MYH7 mutations.

Patent ductus arteriosus

The ductus arteriosus is the physiological connection between the pulmonary arteries and the proximal descending aorta that serves as a right-to-left shunt to allow oxygenated blood from the placenta to bypass the non-ventilated lungs and reach the systemic circulation.

Ductal closure after birth occurs in two steps: initially, functional closure is achieved by constriction of the vascular smooth muscles, typically within 72 hours of birth in 90% of term and 81-87% of healthy preterm infants.106 Removal of the placenta leads to a drop in prostaglandin E2 levels, a potent ductal vasodilator. In addition, the postpartum increase in arterial oxygen tension activates a ductal constrictor mechanism via cytochrome P450 hemoprotein acting as the sensor and endothelin-1 acting as the effector complex as well as via inhibition of voltage-gated potassium channels resulting in depolarization and activation of voltage-dependent calcium channels.107

The second step in ductal closure involves tissue remodeling and leads to permanent, structural closure. Coceani et al.108 describe evidence for involvement of four distinct mechanisms in this step: development of intimal cushions, mechanical solicitation from turbulent blood flow along the narrowing lumen, intramural hypoxia due to the collapse of vasa vasorum in the constricting ductus, and interaction of platelets with the vessel wall.

Adult patency of the ductus arteriosus occurs in about one in 2000 individuals.109 Patent ductus arteriosus usually occurs sporadically, but syndromic associations of this condition have been identified. Chromosomal abnormalities are found in 8 to 11% of cases of patent ductus arteriosus. Furthermore, an association of isolated patent ductus arteriosus with Down syndrome, CHARGE syndrome (acronym for coloboma of the eye, heart defects, atresia of the nasal choanae, retardation of growth/development, genital and/or urinary abnormalities, and ear abnormalities /deafness), Cri-du-chat syndrome, Noonan syndrome, Char syndrome and Holt-Oram syndrome has been documented. The importance of the contractile apparatus in vascular smooth muscle cells for ductal closure is shown by patent ductus arteriosus being associated with mutations in the MYH11 (smooth-muscle myosin heavy chain) and ACTA2 genes (alpha-actin).106

Ventricular septal defect

Ventricular septal defects are the most common non-valvular congenital heart defect that occurs in 1.56 to 53.2 per 1000 live births.110 Characterized by location, ventricular septal defects are classified into membranous ventricular septal defect, muscular ventricular septal defect, inlet ventricular septal defect and infundibular ventricular septal defect.110 Similar to atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects are associated with aneuploidy syndromes (Pateau, Edwards), abnormal chromosomal structure syndromes (del22q11), single gene mutations syndromes (Holt-Oram, Noonan), non-syndromic congenital heart disease with copy number variations and single gene mutations causing isolated congenital heart disease (GATA4, IRX4, TDGF1). As with atrial septal defects, the same three genes involved in cardiac septation (TBX5, NKX2.5 and GATA4) are associated with ventricular septal defects.

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome presents with different degrees of stenosis or atresia of the aortic and mitral valve along with hypoplasia of the left ventricle and ascending aorta. It manifests in three forms classified by the extent of stenosis of the two valves (mitral stenosis/aortic stenosis; mitral stenosis/aortic atresia; mitral atresia/aortic atresia), which differ in prognosis and presentation.

To allow survival of the newborn, especially in the atresia forms, two shunts must be present. One shunt arises at the atrial level allowing mixing of pulmonary venous blood with blood in the right atrium that ultimately is ejected by the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery where the second shunt, an intact ductus arteriosus, provides flow to the systemic circulation (and retrograde flow to the coronary arteries). Chromosomal abnormalities that have been linked to hypoplastic left heart syndrome include Trisomy 13, 18, Turner's syndrome (Monosomy X) and Jacobsen syndrome (terminal 11q deletion). Sporadic cases were found to have mutations that cause dysfunctions in connexin protein 43 or NKX2.111

Noonan syndrome

Noonan syndrome is a complex of congenital heart defect that can be traced to environmental and genetic etiologies. The latter are again subdivided into syndromic congenital heart disease, non-syndromic congenital heart disease, or congenital heart disease secondary to mutations in one gene. But even a “defined” syndrome has a tremendous amount of heterogeneity in the phenotypic expression. Noonan syndrome is associated with cardiac malformations in 80-90% of cases. Defects range from valvular pulmonic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and secundum atrial septal defect (most common) to ventricular septal defect, atrioventricular septal defect, aortic stenosis, aortic coarctation, peripheral pulmonary stenosis, mitral valve abnormalities and coronary artery abnormalities.112,113 It is triggered by a defect in the RAS-MAPK signaling pathway; within this pathway, six genes have been identified as possible mutation targets for Noonan syndrome (PTPN11, SOS1, KRAS, NRAS, RAF1, BRAF), while mutations in two genes (SHOC2, CBL) yield a Noonan-syndrome like phenotype.113 While mutation carriers in the PTPN11 gene are predominantly afflicted with pulmonary stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is more frequently seen in individuals with a RAF1 mutation.113 This collection of genetic variants and clinical phenotypes have been historically coalesced as a single syndrome; yet, it is likely that we will see these further defined and sub-typed in the next decade.

Holt-Oram syndrome

Holt-Oram syndrome has an incidence of 1 in 100,000 live births and presents with bilateral forelimb deformities with congenital heart disease in 75% of individuals.109 Heart defects include atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, cardiac arrhythmias, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, persistent superior vena cava and mitral valve prolapse. The disease arises from a variety of mutations in the T-box transcription factor TBX5 which causes a spectrum of alterations (introduction of premature stop codon that yields a truncated protein that cannot bind to DNA, intragenic duplications that increase gene dosage etc.) depending on the specific genetic abnormality. The interaction of TBX5 with NKX2-5 and GATA4 is required for normal septal development while interaction with MEF2C activates MYH6 expression required for myocardial development.114

Summary

Heart development is a complex process that can be disrupted in many ways, leading to congenital heart disease. With an incidence of 0.4-5% of live births, children afflicted by these disorders are frequently encountered by the anesthesiologist. Gains in knowledge of genetics, embryology, and molecular medicine provide insights into the mechanisms of congenital heart disease. This progress may eventually give rise to novel therapies that specifically target genes or signal transduction pathways involved in these conditions. Unfortunately, congenital heart disease can rarely be tracked to one defined etiology (such as a simple gene mutation) and different influencing factors have to be taken into account.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank James Bell for the design and creation of figures and illustrations that appear throughout this manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL114823) to SCB.

Contributor Information

Benjamin Kloesel, Clinical Fellow, Department of Anesthesia, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Children's Hospital Boston, Boston, MA.

James A. DiNardo, Professor of Anesthesia, Senior Associate in Cardiac Anesthesia; Chief, Division of Cardiac Anesthesia, Department of Anesthesia, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Children's Hospital Boston, Boston, MA.

Simon C. Body, Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesia, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39:1890–900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andropoulos DB, Stayer SA, Russell I, Mossad EB. Anesthesia for Congenital Heart Disease. 2nd. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park MK. Park's Pediatric Cardiology for Practitioners. 6th. Phildadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonas RA. Comprehensive Surgical Management of Congenital Heart Disease. 2nd. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoenwolf G, Bleyl S, Brauer P, Francis-West P. Development of the Heart Larsen's Human Embryology. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2015. pp. 267–303. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadler T. Cardiovascular System. In: Sadler T, editor. Langman's Medical Embryology. 13. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015. pp. 175–217. [Google Scholar]