Abstract

Context

Hospice enrollment for less than one month has been considered too late by some caregivers and at the right time for others. Perceptions of the appropriate time for hospice enrollment in cancer are not well understood.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were to identify contributing factors of hospice utilization in cancer for ≤7 days, to describe and compare caregivers’ perceptions of this as “too late” or at the “right time.”

Methods

Semistructured, in-depth, in-person interviews were conducted with a sample subgroup of 45 bereaved caregivers of people who died from cancer within seven days of hospice enrollment. Interviews were transcribed and entered into Atlas.ti for coding. Data were grouped by participants’ perceptions of the enrollment as “right time” or “too late.”

Results

Overall, the mean length of enrollment was MLOE = 3.77 (SD = 1.8) days and ranged from three hours to seven days. The “right time” group (N = 25 [56%]) had a MLOE = 4.28 (SD = 1.7) days. The “too late” group (N = 20 [44%]) had a MLOE = 3.06 (SD = 1.03) days. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.029). Precipitating factors included: late-stage diagnosis, continuing treatment, avoidance, inadequate preparation, and systems barriers. The “right time” experience was characterized by: perceived comfort, family needs were met, preparedness for death. The “too late” experience was characterized by perceived suffering, unprepared for death, and death was abrupt.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that one more day of hospice care may increase perceived comfort, symptom management, and decreased suffering and signal the need for rapid response protocols.

Keywords: Hospice enrollment, hospice preparedness, awareness of dying

Introduction

The shift to end-of-life care is one of the most difficult and emotional transitions faced on a terminal cancer trajectory. End-stage cancer decisions involve weighing treatment burden and benefits with quality of life and can be influenced by illness-related distress, symptom management, role changes, and disrupted of family cohesion.1 Decisions about end-of-life care are also among the most complex that are made together by clinicians and patients. The sources of this complexity include the imperfect nature of prognostication which remains inexact across diagnoses at the individual level.2 Previous studies have also highlighted the lack of provider-patient discussions about end-of-life preferences3–5 and their occurrence late on the disease trajectory.6

Hospice enrollment has been associated with less aggressive care at life’s end, improved quality of life, and fewer mental health issues in bereavement.7 Yet, the overall median length of hospice enrollment has consistently remained less than three weeks; 10.3% with advanced cancer enrolled for three days or less.8,9 Barriers to earlier hospice enrollment include 1) poor prognostication and insufficient communication with physicians,10,11 2) patient-caregiver perceptions of not being ready, 3) variable definitions of hospice eligibility, 4) varying interpretation of regulations,12 5) providers’ overly optimistic beliefs about survival time,13,14 6) late diagnosis of advanced disease. Earlier hospice enrollments have been found to be impossible for up to one in three hospice patients.11,15 Shorter hospice enrollment and those perceived as too late may result in more unmet needs and difficulty in bereavement.12,16–18

Hospice enrollment for less than one month has been considered too late by only some bereaved caregivers, at the right time for others15,16 and a crisis for some but not all families.19 Hospice enrollment described as too late has been associated with more concerns and lower satisfaction, suggesting that perceptions of the timing—as opposed to the actual length of stay—are associated with the quality of hospice care.16 Perceptions of preparedness for hospice enrollment are intensely personal and not well understood.20 The purpose of the study was to identify factors that contribute to hospice utilization for seven days or less in cancer, to describe and compare family caregivers’ perceptions of “too late” or at the “right time.”

Methods

Design

The study design was exploratory-descriptive, retrospective, and cross-sectional. Data for the analysis were collected during a larger, multipart study that explored hospice decision making in cancer. The overall study sample (N = 275) included subgroups: eligible cancer patients who declined hospice, patient-caregiver dyads, hospice patients without caregivers, and bereaved caregivers whose loved one died within seven days of enrollment whose perceptions are presented in this article. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected.

Procedures

Participants were recruited through a collaborating nonprofit hospice with an average daily census of 600, which provided encrypted contact information for bereaved primary caregivers of people with cancer. Letters describing the study and inviting participation were mailed two months after the death to this subgroup to ensure clear recall of events without being intrusive during acute grief.21,22 Response forms with telephone numbers were return-mailed to the investigator who scheduled interviews. The interview guide had quantitative questions on demographics, diagnosis and length of enrollment, and open-ended questions in three domains: 1) illness trajectory, 2) hospice enrollment decision making, 3) hospice experience (Appendix I). Participants were asked “Was the hospice enrollment too soon, at the right time or too late?” Semistructured in-person interviews lasted an average of 60 minutes. The protocol was approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Analysis

Demographic, diagnostic, and length of enrollment data were entered into SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Frequencies and descriptive statistics were calculated. Interviews were audio recorded and professionally transcribed with consent. Interview transcripts were entered into Atlas.ti 6.2 (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for qualitative data analysis. The iterative coding process involved 1) initial, 2) systematic coding. Initial coding began with multiple readings of the transcripts to understand the narrative. Open coding or the line-by-line review of transcripts was used to identify, name, and describe the phenomena found in text. Systematic coding was conducted using an a priori list of codes that corresponded to the questions on the interview guide so each transcript was evaluated using the same rubric of codes.23 Memos describing early interpretation were entered into Atlas.ti. Saturation or no new emergence of codes was achieved with the sample of 45.

Trustworthiness of the qualitative data analysis was maintained by the use of 1) cocoding of the data by two investigators with regular discussions to establish consensus, 2) an audit trail of analytic decisions, 3) constant comparative analysis to examine contrasts across respondents and groups.24

All interviews were coded using the same iterative process. After coding was complete, the transcripts were divided into two document families (too late and right time) to search for similarities and differences. No participants selected too soon. Matrices were created for each group in which the rows were cases and the columns were variables that emerged from coding: diagnosis, hospice decision, reason for short enrollment, dying process, and place of death. Brief descriptive units of text were entered in each cell. Cross-case analysis yielded themes which illuminated similarities and differences of contributing factors and experiences with short hospice enrollment (e.g., perceptions of comfort, preparedness).25 An independent samples t-test was used to determine if differences in the mean length of enrollment (in days) were statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Variables | Right Time (N = 25) | Too Late (N = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospice MLOE | 4.28a (SD = 1.7) |

3.06a (SD = 1.8) |

| Hospice range | 1–7 | 1–6 |

| Place of death | ||

| Home | 12 (48%) | 12 (60%) |

| Hospice inpatient unit | 7 (28%) | 3 (15%) |

| Hospice bed in hospital | 6 (24%) | 3 (15%) |

| Nursing home | 0 | 2 (10%) |

| Patient age | 75.68 (SD = 70.75) |

74.55 (SD = 8.45) |

| Caregiver age | 63.44 (SD = 11.05) |

57.45 (SD = 13.4) |

| Patient gender | ||

| Male | 17 (68%) | 13 (65%) |

| Female | 8 (32%) | 7 (35%) |

| Caregiver gender | ||

| Male | 4 (16%) | 1 (5%) |

| Female | 21 (84%) | 19 (95%) |

| Patient race | ||

| White | 23 (92%) | 20 (100%) |

| African American | 1 (4%) | |

| Native American | 1 (4%) | |

| Caregiver race | ||

| White | 24 (96%) | 20 (100%) |

| African American | 1 (4%) | |

| Native American | ||

| Patient education | ||

| Did not finish HS | 3 (12%) | 0 |

| HS | 12 (48%) | 9 (45%) |

| Some college | 4 (16%) | 6 (30%) |

| College degree | 2 (8%) | 4 (20%) |

| Graduate degree | 4 (16%) | 1 (5%) |

| Caregiver education | ||

| High school | 7 (28%) | 5 (25%) |

| Some college | 4 (16%) | 5 (25%) |

| College degree | 5 (20%) | 5 (25%) |

| Graduate degree | 9 (36%) | 4 (20%) |

| —missing 1 | ||

| Patient religious preference | ||

| Roman Catholic | 9 (36%) | 13 (65%) |

| Other denominational Christian | 11 (44%) | 3 (15%) |

| Other | 1 (4%) | 4 (20%) |

| No preference | 4 (16%) | |

| Caregiver religious preference | ||

| Roman Catholic | 11 (44%) | 13 (65%) |

| Other denominational Christian | 11 (44%) | 4 (20%) |

| Other | 1 (4%) | 2 (10%) |

| No preference | 2 (8%) | 1 (5%) |

| Caregiver relationship | ||

| Wife | 13 (52%) | 9 (45%) |

| Husband | 2 (8%) | 1 (5%) |

| Daughter | 6 (24%) | 10 (50%) |

| Son | 1 (4%) | |

| Other | 3 (12%) | |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Lung | 10 (40%) | 7 (35%) |

| Pancreatic | 3 (12%) | 3 (15%) |

| Breast | 0 | 2 (10%) |

| Prostate | 4 (16%) | 2 (10%) |

| Leukemia | 2 (8%) | 1 (5%) |

| Otherb | 6 (24%) | 5 (25%) |

P < 0.05.

Kidney, bladder, myeloma, liver, rectal, intestinal, unknown.

Results

Sample

The sample included the primary caregivers of 45 hospice patients who died from cancer within seven days of hospice enrollment. Patient age ranged from 58 to 91 years and the Mage was 74.8 years. Caregivers’ ages ranged from 30 to 85 and the Mage was 60.7 years. The majority of hospice patients (96%) and caregivers (98%) were white. The majority of hospice patients were male (67%) and caregivers were female (89%). Religious preference was Roman Catholic for 48% of the hospice patients and 54% of caregivers. The most common cancer diagnoses were as follows: lung cancer (N = 17 [37.8%]); prostate cancer (N = 6 [13.3%]) and pancreatic cancer (N = 6 [13.3%]) (Table 1).

Overall, the mean length of enrollment was MLOE = 3.77 (SD = 1.8) days and ranged from three hours to seven days. The “right time” group (N = 25 [56%]) had a MLOE = 4.28 (SD = 1.7) days. The “too late” group (N = 20 [44%]) had a MLOE = 3.06 (SD = 1.03) days. Group differences in length of enrollment were statistically significant (P = 0.029).

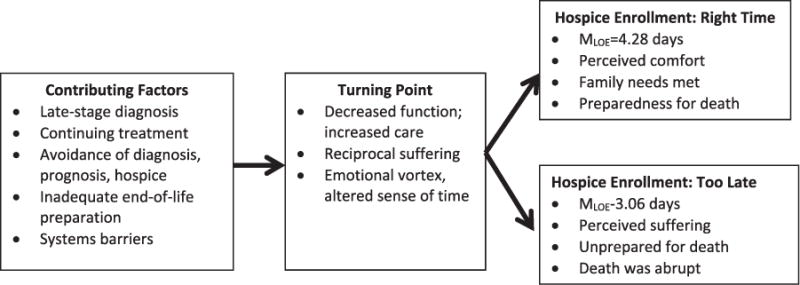

A conceptual model of the contributing factors that led to a turning point, hospice enrollment, and perceptions of “right timing” or “too late” is described and illustrated with quotes from different representative participants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The contributing factors and perceptions of short hospice enrollment for cancer patients.

Short Hospice Enrollment

The contributing factors that preceded hospice enrollment within one week of death included late-stage diagnosis, continuing treatment, avoidance, inadequate preparation, and systems barriers.

Late-Stage Diagnosis

Sixteen (35%) of the patients were initially diagnosed less than one month before death. Participants described observations of major physical and functional decline but no awareness of cancer. At diagnosis, the cancer was advanced, and in some situations, providers were investigating the full extent of disease and planning treatment when the person died. This participant illustrated shock about the late diagnosis, “They came in and told us he was loaded with cancer. How does a man go from not knowing anything to having Stage IV cancer?” Another participant described the rapid succession following a late-stage diagnosis, “In that two week span they found out that he had a tumor on his pancreas that was blocking the duct to his liver, that’s why he was jaundiced. It happened boom-boom-boom.” In all situations, when the cancer was diagnosed less than a month before death, there was a sharp terminal decline with little time for end-of-life care.

Continuing Treatment

Treatment that continued well into the dying phase was described as contributors to short hospice enrollment. Treatment was encouraged by the provider but only desired in some cases. There was tension between the simultaneous processes of active treatment and dying. This caregiver described her dismay with an aggressive plan to remove her husband’s bladder near the end of his life.

We went for the preoperative tests and were there all day; it was grueling. Eventually we saw the anesthetist who could see right away that he would never make it because he explained that surgery. The surgeon had never said what this entailed.

Another caregiver illuminated the uncertainty that people face with decision making while grasping an unfolding reality, “There was part of me that thought, he can’t get back from here. But then I thought, if he really ate and worked hard, he might have quality of life going forward.” The nature of continuing treatment when a person is actively dying created uncertainty about what was happening.

Avoidance

Participants described avoidance of discussing the diagnosis, prognosis, or hospice by the patient, family, or provider and the difficulty of talking about a terminal illness, no possible cure, and impending death. Participants also described loved ones who experienced physical symptoms but avoided seeing a physician or seeking a diagnosis. Knowledge that something was happening coincided with avoiding medical attention, “A year ago I kept saying, ‘Mom, you shouldn’t be out of breath.’ She’d say, ‘It’s nothing and sluff it off.’ I said ‘Let’s tell the doctor.’ ‘No, I’m fine.’” This caregiver illustrated the tendency of some dying people to hold back information, potentially to avoid hurting another.

I noticed how much his weight was dropping and that he was becoming more frail, but I attributed it to his age. He was very private and protective of me. When I would ask, he would throw out enough to make me curious but I couldn’t get anything concrete about what was going on.

Directly addressing a loved one’s decline was difficult. Participants described a tendency to avoid talking about the hard realities of a terminal illness because if circumvented it was not “real”; avoidance contributed to later hospice enrollment.

Inadequate End-of-Life Preparation

When providers do not initiate conversations about an approaching death, give patients and families clear information about the prognosis, or describe the illness progression, it creates a gap between understanding and expectation. People live with hope for a cure or for more time than is realistic. This participant described how her father’s physician left her without a clear picture days before his death,

Dr. T came in and said he didn’t know what was going to happen and what about sending him to Hospice. I thought he could go and just get better. On the other hand, I thought he was dying. I didn’t know what to think.

Inadequate preparation about an approaching death prolonged consideration of hospice enrollment and left caregivers with great uncertainty.

Systems Barriers

Caregivers of people who were dying but still receiving restorative care experienced confusion about hospice eligibility. Eligibility for hospice required that the person not be receiving cure-focused treatment. People who are enrolled in a Skilled Nursing Facility for rehabilitation or Certified Home Health Care are not eligible.

It was very confusing … my comprehension was that we would pay $10,000 a month for him to live in this residence and he would get Hospice, or he could get Hospice but no therapy.

Caregivers also described perceptions that fiscal incentives drove patient care. Immediately after learning a terminal diagnosis, this caregiver felt pressure to move her father but hospice was not suggested by the hospital, “The message was, ‘We can’t help him. We don’t want to take care of him because we can’t get paid to do that for very long.’ It was all about the money.” Regulations that were barriers to hospice enrollment created frustration for caregivers who were trying to grasp life-changing events.

Turning Point

Several pivotal factors contributed to a turning point and realization of the need for hospice enrollment: marked functional decline, reciprocal suffering, and an emotional vortex.

Functional Decline

The dying person’s decreasing functional abilities intensified the need for hands on care with activities of daily living. Participants described the heavy emotional and physical toll accompanying this transition. Assistance with toileting and bathing became difficult to manage, changed the dying person’s self-image, and were perceived as an affront to dignity. This caregiver described being overwhelmed, “His need for bathing, feeding and swallowing was beyond my abilities.” Another illustrated the difficulty of the terminal decline, “I think when he went into diapers that was the turning point for him. I think he couldn’t bear it, a grown man. Who the hell wants to live at the end like that?” Increasing functional decline became a catalyst for hospice enrollment.

Reciprocal Suffering

Caregivers who observed a loved one’s suffering, symptom exacerbations, and pain described feelings of reciprocal suffering that precipitated hospice enrollment. The pain (not all physical) and emotions were shared. This caregiver’s mother was dying and her father had a kidney stone. She described their mutual suffering, “She was concerned about him. I said “Mom, he doesn’t want you to know he’s sick.” She couldn’t get off the couch so she slept there, Dad slept on the floor holding her hand. It was heartbreaking.” This caregiver described watching her mother’s unbearable pain, helplessness, frustration during a hospitalization that preceded hospice enrollment, “My mother was tearing at her hair, tearing her hose out of her face, tearing her clothes off and she had a very high level of anxiety. She was bleeding out and starting to asphyxiate. “This caregiver described her own overwhelming anxiety. Observing a loved one’s uncontrolled symptoms precipitated reciprocal suffering and recognition of the need for hospice.

Emotional Vortex

Participants described the turning point as a vortex of overwhelming emotions and an altered perception of time passage as the hospice enrollment occurred. A caregiver recalled the unreality of the situation by saying, “It’s weird because I was in never-never land.” Participants described the turning point as an overpoweringly emotional time with many simultaneous intense feelings, “I was devastated. I knew he was worsening, I knew it wasn’t going to be good but I still thought there were options.” This caregiver described her perceptions of the time preceding hospice enrollment, “A nurse took me aside. It was like having an out of body experience because I didn’t realize things were moving so quickly. Then they brought a Hospice nurse in.” Participants described an altered sense of time when everything was changing quickly. This caregiver illustrated what many expressed, “I’m still amazed. I’m still trying to reconcile it in my head because it happened so fast.” This caregiver characterized her altered sense of time, “It sounds funny when here I tell you this 10-year story of his illness; it feels like he died suddenly. We weren’t ready; it felt like it happened all of a sudden. “Hospice enrollment followed an emotional vortex.

Hospice Enrollment: Right Time

The “right time” experience was characterized by perceived comfort, family needs met, prepared for death.

Comfort

All participants who said that the hospice enrollment was at the right time recalled that their loved one’s pain and other symptoms were managed and that the person was comfortable and not suffering. This participant’s words are representative, “His death was peaceful. He was in no pain. Hospice was more than helpful.” Another participant reflected on the importance of her husband’s comfort, “He was kept comfortable and had us around him; that’s huge.” Recall of a loved one’s death as comfortable and without pain or suffering was reassuring.

Family Needs

Participants who believed a loved one’s hospice enrollment was at the right time expressed satisfaction with hospice. This caregiver illustrated how Hospice met her family’s needs, “The men who brought the furniture, the oxygen people and Hospice were wonderful. I called in the middle of the night and the nurse came over—there were nights when I needed help because I was by myself.” This caregiver described how her family’s needs were met in the inpatient unit,

They asked me if I wanted to stay in the room next to the bed, and I said yes. My daughter said “I’d like to stay,” so they brought her a cot. She was on one side and I was on the other holding his hand.

Participants in the “right time” group expressed satisfaction with and appreciation for hospice care.

Preparedness for Death

Participants in the “right time” group described how the person’s preparedness for the approaching death and desire to talk about dying eased the transition. This caregiver illustrated his wife’s awareness,

She woke me at 4 AM and said, “I want to talk.” She talked about the kids, how wonderful it is to have everybody there … Then she said, “I’m tired.” At 6:20 AM she went into a comatose state, had trouble breathing and we called Hospice. She died at 3:20 PM. It was remarkable that she wanted to get that all out.

Participants in the “right time” group described recognition of the approaching death and its inevitability.

Hospice Enrollment: Too Late

The “too late” experience was characterized by perceived suffering; unprepared for death, death was abrupt.

Perceived Suffering

Participants who believed that their loved one’s hospice enrollment was too late gave examples of unmanaged symptoms and suffering. This caregiver characterized suffering as, “He did not have time. He didn’t go at peace; he went in a panic.” Caregivers described pain, agitation, and fear. This participant’s illustrated her father’s agitation after a move to an inpatient bed,

My dad was crazed, out of sorts, out of his mind. He was so mad at me. He said, “You shouldn’t have moved me.” He was angry, upset, distraught, disturbed. He grabbed my wrist, wouldn’t let go, and tried to hit me.

Participants in the “too late” group described insufficient time for the symptoms to be managed, leaving them with memories of a loved one’s suffering at life’s end.

Unprepared for Death

Participants who described being unprepared had a minimal assistance before the death. This participant described having only one hospice visit before her father’s death, “He enrolled him over the telephone right there with the surgeon. A nurse came but that’s all. He was gone before the nurse could do anything.” Another participant’s words illustrated being unprepared, “When I said my mother’s deteriorating in front of my eyes—that should have been the point when somebody intervened.” Participants in the too late group described feeling surprised and unprepared for the death.

Death Was Abrupt

Participants who perceived the hospice enrollment as too late described death happening unexpectedly. Participants in the too late group described feeling shocked and stunned. This caregiving wife called Hospice on the day of her husband’s death and recalled how abruptly it occurred.

When the nurse from Hospice came she had bundles of supplies, medications and documents. I had to fill out all of these documents and listen to instructions. I would much rather have been with my husband at that time. She left and an hour later he was dead.

Absent adequate preparedness, participants described the death as sudden and unforeseen.

Discussion

This study identified factors that contributed to hospice enrollment of seven days or less for people with cancer and compared perceptions of this being too late and at the right time. Factors contributing to late enrollments were as follows: late-stage diagnosis; continuing treatment; avoidance of the diagnosis, prognosis or hospice; inadequate end-of-life preparation; and systems barriers. Decreasing functional abilities and increasing needs for care precipitated a turning point and hospice enrollment. Participants who felt the hospice enrollment was at the right time described a loved one’s comfort, acknowledged that their family’s needs were met and they were prepared for the death. Participants, who felt the enrollment too late recalled the loved one’s suffering, felt unprepared for the death and experienced the death as abrupt. Differences in the mean length of hospice enrollment in the right time and too late groups (3.06 vs. 4.28 days) aligned with differential perceptions of the hospice experience. The findings suggest that one more day of hospice care may increase perceived comfort, symptom management, and decrease suffering.

These findings build on previous studies of short hospice enrollment that have identified similar contributing factors before hospice consideration and extend knowledge about the complexity of late hospice enrollment.10,11,19 The transition from “needing assistance” to “total care” may be the indicator of imminent mortality and timeliness of hospice enrollment.20,26,27

Findings from the comparative analysis of eligible cancer patients who declined with those enrolled in hospice (another subgroup of this study) revealed that awareness of the time for hospice emerged from a combination of internal and external cues.28 External cues included information provided by physicians who recognized the impending end of life and shared that information clearly with patients and caregivers. In some cases, the provider initiated the referral and offered support to the caregiver about the decision. In contrast, this analysis of caregivers whose family member enrolled in hospice for a week or less reported that such communication was absent or unclear. The same experience of functional decline preceded the hospice decision in both sample subgroups but the time trajectory of this decline was compressed in this group. Although rapid illness progression may be inevitable in some situations, preparation and support may help ameliorate its adverse impacts.7,16

Preparedness for hospice involved awareness of the approaching death and the desire to talk about what was happening. “Awareness of dying” has been defined as knowing that death is imminent within hours or days;29 it has been associated with acceptance of dying30 and found to reduce the number of undesirable interventions;31 most who recognize that they are dying do not want aggressive care.3 Glaser and Strauss32 theorized that awareness of dying developed through interactions between people who are dying, their families and providers in patterns: closed awareness, suspected awareness, mutual pretense awareness, and open awareness.32 Open or mutual awareness of dying may facilitate in-the-moment decisions about hospice, shifting the focus toward preparation.33 Billings and Bernacki posit that the right timing of interventions profoundly improve their value.34 Awareness of dying may precipitate hospice enrollment.

Preparedness mediated perceptions of “right time” and “too late.” These findings raise questions about how being prepared for an approaching death may also catalyze conversations about patient-caregiver wishes for continuing treatment, symptom management, and place of death, thus generating mutual understanding and congruence. The concept of congruence in end-of-life care has most often been associated with patients’ wishes about place of death.35–38 However, achieving congruence between patient-caregiver wishes about all aspects of end-stage care may inform readiness for hospice enrollment and adaptation in bereavement.3

Limitations

The study limitations include a racially homogeneous sample. There are likely additional emergent perceptions about hospice preparedness and timing that would emerge with a more diverse sample. The sample was drawn from only one hospice organization. The exploration of organizational and regional differences would add to the knowledge base about the complexity of preparedness for hospice. Postdeath interviews allowed discovery of only caregivers’ perspectives. Although patient voices would be difficult to access at the very end of life, this perspective would be deeply informative. Finally, the cross-sectional design with only one participant encounter may limit understanding of caregivers’ perceptions.

Implications

The knowledge that one additional day of hospice enrollment may possibly make a difference in bereaved caregivers’ memories of a loved one’s comfort and suffering underscores the need for prognostication and provider communication. The importance of honest patient-family-provider conversations about the realities of terminal cancer and goals of care cannot be understated. Longer hospice enrollment may potentiate more optimal clinical outcomes but the reality of short enrollment remains, suggesting the importance of viewing them as an opportunity and recognition that for some, short enrollment precisely meets needs. These findings suggest the importance of rapid hospice response protocols involving astute assessment of dying, efficient techniques for symptom management, and the amelioration of suffering. When time is of the essence, hospice enrollment should be streamlined, foregoing paperwork for attention to patient-family needs.

Policy changes that would institute payment for simultaneous cancer treatment and palliation care are under study through a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid demonstration project titled Medicare Care Choices. Available co-occurring treatment and palliation may help eliminate the emotional tension accompanying the forced choice that exists with current hospice eligibility requirements.26 Moreover, policy change could potentially be a catalyst for addressing misunderstandings of hospice and palliative care that become barriers to enrollment.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, challenge grant RC1NR011647-01.

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from Hospice Buffalo, the Buffalo Center for Social Research, and 45 bereaved caregivers.

Appendix I: Interview Guide

-

Illness Trajectory

(L) Please tell me the history of your loved one’s illness.-

➢How and when did they begin?

-

➢Gradual or sudden onset?

(L) How did you learn of his or her diagnosis?-

➢How and when was the diagnosis made?

-

➢What was the diagnosis?

(L) Please tell me how your loved one’s illness was treated?-

➢Was your loved one in the hospital?

-

➢Did she/he have chemotherapy/radiation and/or surgery?

(L) What illness-related changes did you observe?-

➢What physical and functional changes happened?

-

➢What psychosocial and emotional changes happened?

-

➢How did you learn that the cancer had become advanced?

-

➢

-

Hospice Decision Making

(L) How/when was hospice suggested or introduced? By whom?

(L) How did you, your loved one, and family respond to a possible hospice enrollment?

-

Hospice Experience

(L) How did the situation change during the hospice enrollment?

(L) What was your experience with hospice?

(L) Was the hospice enrollment _____too soon, _____at the right time, or _____too late?

To summarize, would you have any advice or wisdom you could share with another caregiver who is experiencing what you and your loved one did?

Note: (L)-leading questions; ➢probing questions.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siminoff LA, Zyzanski SJ, Rose JH, Zhang AY. Measuring discord in treatment decision-making; progress toward development of a cancer communication and decision-making assessment tool. Psychooncology. 2006;15:528–540. doi: 10.1002/pon.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothenberg LR, Doberman D, Simon LE, Gryczynski J, Cordts G. Patients surviving six months in hospice care: who are they? J Palliat Med. 2014;17:899–905. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;303:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. Dying in America; pp. 11–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson HG, et al. Communication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: when do discussions occur and what is said? J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1176–1185. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma RK, Dy SM. Documentation of information and care planning for patients with advanced cancer: associations with patient characteristics and utilization of hospital care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2011;28:543–549. doi: 10.1177/1049909111404208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4457–4464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman DC, Morden NE, Chiang-Hua C, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Trends in cancer care near the end of life. In: Bronner KK, editor. Dartmouth atlas for healthcare. Lebanon, NH: The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2013. pp. 1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO’s facts and figures: Hospice care in America. Arlington, VA: NHPCO; 2014. pp. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schockett ER, Teno JM, Miller SC, Stuart B. Late referral to hospice and bereaved family member perception of quality of end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teno JM, Casarett D, Spence C, Connor S. It is “too late” or is it? Bereaved family member perceptions of hospice referral when their family member was on hospice for seven days or less. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Why don’t patients enroll in hospice? Can we do anything about it? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1009–1019. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson TM, Alesander SC, Hays M, et al. Patient-oncologist communication in advanced cancer: predictors of patient perception of prognosis. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1049–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0372-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldrop DP. At the eleventh hour: psychosocial dynamics in short hospice stays. Gerontology. 2006;46:106–114. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teno JM, Shu JE, Casarett D, et al. Timing of referral to hospice and quality of care: length of stay and bereaved family members’ perceptions of the timing of hospice referral. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casarett D. Understanding and improving hospice enrollment. LDI Issue Brief. 2005;11:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Gunten CF, Lutz S, Ferris FD. Why oncologists should refer patients earlier for hospice care. Oncology. 2011;25:1278–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waldrop DP, Rinfrette ES. Can short hospice enrollment be long enough? Comparing the perspectives of hospice professionals and family caregivers. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:37–47. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell ML. “It’s not time”: delayed hospice enrollment. J Pall Med. 2014;17:874–875. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.9415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, et al. A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;24:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George LK. Research design in end-of-life research: state of science. Gerontology. 2002;42:86–98. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cresswell JW, editor. Research design: Qualitative & quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks,CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padgett DK. Qualitative methods in social work research: Challenges and rewards. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casarett D, Fishman JM, Lu HL, et al. The terrible choice: re-evaluating hospice eligibility criteria for cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:953–959. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.8079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teno JM, Weitzen S, Fennell ML, Mor V. Dying trajectory in the last year of life: does cancer trajectory fit other diseases? J Palliat Med. 2001;4:457–464. doi: 10.1089/109662101753381593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waldrop DP, Meeker MA, Kutner JS. The developmental transition from living with to dying from cancer: hospice decision-making. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015;33:576–598. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2015.1067282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellershaw J, Ward C. Care of the dying patient: the last hours or days of life. BMJ. 2003;326:30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lokker ME, vanZuylen L, Veerbeek L, van der Rijt CC, van der Heide A. Awareness of dying: it needs words. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1227–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verbeek L, VanZuylen L, Swart SJ, et al. Does recognition of the dying phase have an effect on the use of medial interventions? J Palliat Care. 2008;24:94–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glaser B, Strauss A. Awareness of dying. Chicago: Aldine; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Billings JA, Bernacki R. Strategic targeting of advance care planning interventions: the Goldilocks phenomenon. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:620–624. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell CL, Somogyi-Zalud E, Masaki EH. Factors associated with congruence between preferred and actual place of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomes B, Canlanzani N, Gysels M, Hall S, Higginson IJ. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer S, Min SJ, Cervantes L, Kutner J. Where do you want to spend your last days of life? Low concordance between preferred and actual site of death among hospitalized adults. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:178–183. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomes B. Higginson IJ where people die (1974–2030): past trends, future projections and implications for care. Palliat Med. 2008;22:33–41. doi: 10.1177/0269216307084606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]