Abstract

Objectives

We explored whether state laws allowing pharmacists to administer human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations to adolescents are associated with a higher likelihood of HPV vaccine uptake.

Methods

We examined provider-reported HPV vaccination among 13 to 17 year olds in the National Immunization Survey-Teen: 2008–2014 for girls (N=48,754) and 2010–2014 for boys (N=31,802). Outcome variables were HPV vaccine initiation (≥ 1 dose) and completion (≥ 3 doses). The explanatory variable of interest was a categorical variable for the type of pharmacist authority regarding HPV vaccination for adolescents (< 18 years) in the state: not permitted (reference), by prescription, by collaborative practice protocol, or independent authority. We ran separate difference-in-difference regression models by sex.

Results

During 2008–2014, 15 states passed laws allowing pharmacists to administer HPV vaccine to adolescents. Pharmacist authority laws were not statistically significantly associated with increased HPV vaccine initiation or completion.

Conclusions

As currently implemented, state laws allowing pharmacists to administer HPV vaccine to adolescents were not associated with uptake. Possible explanations that need further research include restrictions on pharmacists’ third-party billing ability and the lack of promotion of pharmacy vaccination services to age-eligible adolescents.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, HPV vaccine, vaccination laws, pharmacist, pharmacy practice, difference-in-difference

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually-transmitted infection in the United States (U.S.), causing around 300,000 new cases of genital warts and 26,000 cancers (anal, cervical, oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar) each year in men and women.1 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended routinely vaccinating all girls ages 11–12 with HPV vaccine since 2007. Catch-up vaccination is recommended for females aged 13 to 26 years who have not been previously vaccinated. Permissive recommendations were added for boys in 2009 and routine recommendations for boys came in 2011. The recommended age for boys is 11 to 12 years with catch-up vaccination recommended for males aged 13 to 21 years.2 Despite the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness, HPV vaccination coverage is far below the national objective set by Healthy People 2020. In 2014, completion of the three-dose series among adolescents ages 13 to 17 was only 40% for girls and 22% for boys.3 HPV vaccination coverage also lags far behind childhood and other adolescent vaccines.3 The reasons for underuse of HPV vaccine are complex as several factors affect vaccine uptake.4,5

Recently, the President’s Cancer Panel and the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) recommended expanding HPV vaccination to pharmacies as one strategy to improve vaccination coverage.6 Pharmacies have particular advantages that make them appealing for HPV vaccination for adolescents. An estimated 250 million visits are made to pharmacies each week, and around 93% of Americans live within 5 miles of a pharmacy,7 exhibiting the likelihood of high accessibility among the U.S. adolescent population.8 Pharmacies also have longer hours of operation and typically do not require an appointment unlike most medical clinics.9 Additionally, one study characterizing vaccination visits at a national pharmacy chain showed that over 6 million total vaccine doses (85% influenza, 15% other vaccines) were administered to adults over the one year study period, providing further evidence of the capacity that pharmacies are able to provide in vaccination efforts.10 Another study found that pharmacist provision of influenza vaccination increased among adolescents after they were given the legal authority in Oregon.11 With the success of vaccination of adults in pharmacies over the past two decades, the President’s Cancer Panel and NVAC’s recommendation for expanding HPV vaccinations to pharmacies seems promising. However, we know of no published studies quantifying the use of pharmacies for HPV vaccinations among age-eligible adolescents.

Independent of such recommendations, many states have expanded pharmacists’ vaccination authority for adolescents, including HPV vaccination.9 Pharmacists’ vaccination authority to administer vaccines is typically one of four types: not permitted, by prescription, by collaborative practice protocol, or independent authority. In states where vaccination is not permitted, pharmacists may not administer the vaccine under any circumstances. In prescription-only states, pharmacists are allowed to administer the vaccine only to adolescents who present a prescription from a prescriber (e.g., physicians). In states with collaborative practice protocol laws, pharmacists may administer the vaccine to patients of a prescriber upon the signing of a supervision agreement with that prescriber, which may, depending on the state, include standing orders, protocols, collaborative agreements, or similar documents. In states where pharmacists have independent authority to administer HPV vaccines to adolescents, pharmacists may administer the vaccine without prior approval from a prescriber.

While the legal authority to administer HPV vaccine is a minimum requirement to meet the policy recommendations, effective use of these services will depend on a host of factors including consumer awareness of vaccination services in pharmacies and reimbursement policies. The population impact of expanding pharmacists’ practice to administer HPV vaccine to adolescents is unknown. Our study explores whether state laws that allow pharmacists to administer HPV vaccine to adolescents were associated with higher likelihood of HPV vaccination.

METHODS

Data sources

The National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) is a national survey administered every year by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics to estimate current vaccine coverage for adolescents aged 13 to 17 years. These data are collected in two phases: 1) telephone interview of a random sample of U.S. households and 2) vaccination history from current medical provider via mail. Sociodemographic information, along with vaccination beliefs and attitudes, behaviors, and the teen’s vaccination history are collected from the telephone interview. In the second phase, with the parent or guardian’s permission, NIS-Teen contacts the adolescent’s primary care provider by mail, asking them to complete and return a provider verified vaccination record (Provider-Immunization History Questionnaire). We examined HPV vaccination within the provider-reported sample for years following recommendation by ACIP: 2008 through 2014 for girls and 2010 through 2014 for boys. Response rates for the provider information range from 52.3% to 62.0% over the study years.12

We generated analytic vaccination law data directly from each state’s pharmacy practice statutes. First, one of the authors (WAC, lawyer) identified the pharmacy practice law pertaining to pharmacist-administered vaccinations using the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation LawAtlas database and LexisNexis. Next, a second author (PDS, licensed pharmacist) verified the state’s vaccination law and coded the law based on pharmacist’s practice authority to administer HPV vaccine to adolescents. This initial coding was revised by one of the authors (WAC) and any discrepancies were resolved between authors (WAC and PDS). We then cross-referenced our coding schema with available information on this topic from the American Pharmacists Association and the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations State Immunization Authority Annual Survey. Laws in effect in the 50 states and the District of Columbia between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2014 were included in analyses.

Measures

Outcome variables were indicators for HPV vaccine series initiation (≥ 1 dose) and completion (≥ 3 doses) as reported by a health care provider in NIS-Teen. The explanatory variable of interest was a categorical variable for the type of pharmacist authority regarding HPV vaccination for age-eligible adolescents: not permitted (reference), by prescription, by collaborative practice protocol, or independent authority. The coding scheme was developed from an adapted definition that characterized the level of vaccination authority given to pharmacists.9 We also analyzed an alternate coding with a single indicator for state-years with any type of pharmacist authority to administer HPV vaccinations to adolescents.

Demographic and health characteristics for the index child included sex; indicators for each year of age; race and ethnicity (Non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other/unspecified); number of health care visits in the past year (range 1 to 9); receipt of influenza vaccination in the current season, receipt of Tdap and meningococcal vaccinations; and health insurance status (private, Medicaid, other public insurance, uninsured, or unspecified or missing). At the parental level, we included mother’s education (less than high school, high school diploma, some college, or college degree or higher). Finally, for household characteristics, we assessed household income (≤ $25,000, $25,001–$50,000, $50,001–$75,000, or ≥ $75,001, household size (range 2 to 8 or more), and number of children in the household (1, 2 or 3, or 4 or more).

Statistical analysis

We estimated difference-in-differences linear probability models to identify the effect of changes in state-level pharmacist vaccination authority on individual HPV vaccination outcomes. The difference-in-differences approach compares changes in HPV vaccination outcomes before and after a state enacted a law to changes over the same time period in states that did not enact a law. We ran separate models for boys (N=31,802) and girls (N=48,754), HPV vaccine initiation and completion outcomes, and for both measures of pharmacist authority laws (8 total models). In the main analyses, states with pharmacist provision laws for the entire study period (k=14) were excluded because we could not observe differences in HPV vaccination rates pre- and post-enactment. In sensitivity analyses, we also estimated the models using the full sample of adolescents in all states and the District of Columbia.

All models adjusted for indicator variables for state and year, state-specific time trends (i.e., interactions between state indicators and year as a continuous variable), state-level school entry requirements for meningococcal13 and Tdap vaccines,14 and the variables listed above in Measures. Analyses were weighted using the provider-reported sample weights in NIS-Teen and standard errors were clustered by state. We conducted our analyses using Stata version 14.0 (College Station, TX). All statistical tests were two-tailed with a critical alpha equal to 0.05. The study was deemed not human subjects research by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

The HPV vaccine initiation rate in our analysis sample was 38.0% (48.5% female and 19.7% male); the completion rate was 22.4% (30.6% female and 8.3% male) (Table 1). Over three quarter of respondents lived in state-years that did not have any pharmacist vaccine authority (76.5%). Pharmacist vaccination authority through a protocol was the most common type of provision (14.9%), followed by prescription only (5.8%) and independent authority (2.8%).

Table 1.

Sample Vaccination and Demographic Characteristics, NIS-Teen, 2008–2014

| N | Weighted % | Weighted Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV vaccination | ||||

| Initiation (≥ 1 doses) | 31,113 | 38.0 | – | – |

| Female | 24,676 | 48.5 | – | – |

| Male | 6,437 | 19.7 | – | – |

| Completion (≥ 3 doses) | 18,913 | 22.4 | – | – |

| Female | 16,147 | 30.6 | – | – |

| Male | 2,766 | 8.3 | – | – |

| Vaccination authority type | ||||

| No authority | 61,155 | 76.5 | – | – |

| Prescription only | 4,199 | 5.8 | – | – |

| Protocol | 11,756 | 14.9 | – | – |

| Independent authority | 3,905 | 2.8 | – | – |

| School entry requirements | ||||

| Tdap vaccination | 53,713 | 68.3 | – | – |

| Meningococcal vaccination | 23,714 | 25.8 | – | – |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 31,949 | 36.7 | – | – |

| Female | 49,066 | 63.3 | – | – |

| Age | ||||

| 13 years old | 16,338 | 19.6 | – | – |

| 14 years old | 16,814 | 20.1 | – | – |

| 15 years old | 16,400 | 20.8 | – | – |

| 16 years old | 16,577 | 20.9 | – | – |

| 17 years old | 14,886 | 18.6 | – | – |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 55,463 | 60.1 | – | – |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 8,162 | 16.0 | – | – |

| Hispanic | 10,452 | 16.4 | – | – |

| Other or Unspecified | 6,938 | 7.5 | – | – |

| Health care visits | 80,556 | – | 2.83 | 0.01 |

| Receipt of Influenza vaccine (current season) | 3,722 | 3.9 | – | – |

| Receipt of Tdap vaccine | 69,120 | 85.1 | – | – |

| Receipt of meningococcal vaccine | 55,644 | 67.5 | – | – |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 46,750 | 50.6 | – | – |

| Medicaid | 21,095 | 31.9 | – | – |

| Other public insurance | 8,518 | 9.9 | – | – |

| Uninsured | 3,773 | 6.4 | – | – |

| Unspecified or missing | 879 | 1.2 | – | – |

| Parent characteristics | ||||

| Mother's education | ||||

| Less than high school | 7,573 | 11.9 | – | – |

| High school diploma | 15,127 | 25.7 | – | – |

| Some college | 22,444 | 26.6 | – | – |

| College degree or higher | 35,871 | 35.9 | – | – |

| Household characteristics | ||||

| Income | ||||

| Less than 25,000 | 13,302 | 22.0 | – | – |

| $25,001 – $50,000 | 14,678 | 20.5 | – | – |

| $50,001 – $75,000 | 12,736 | 15.0 | – | – |

| $75,0000 or more | 35,651 | 35.4 | – | – |

| Unspecified or missing | 4,648 | 7.1 | – | – |

| Household size | 81,015 | – | 4.40 | 0.01 |

| Number of children | 81,015 | – | 1.80 | 0.00 |

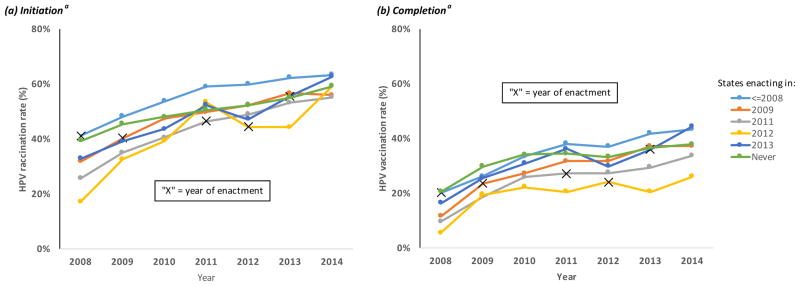

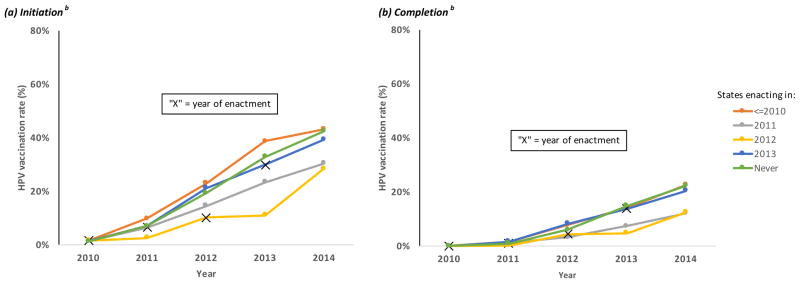

Between 2008 and 2014, 15 states passed laws allowing pharmacists to administer HPV vaccine to adolescents, 22 states did not have pharmacist provision laws and 14 states had pharmacist provision laws for the entire period. Figure 1 shows unadjusted HPV vaccination rates over time with each line representing a different group of states defined by the effective date of the pharmacist vaccination authority law, including a group for states that never passed such laws. No states passed pharmacist authority laws in 2010. Figures 1 and 2 include separate panels for initiation vs. completion of the HPV vaccine for girls and boys respectively. In each series, “X” indicates the year of passage of the law. Overall, there was a general upward trend in HPV vaccination for each sex, outcome, and group of states. States that passed pharmacist provision laws prior to our analysis period (2008 for girls and 2010 for boys), tended to have higher initiation rates than states that never passed laws or passed laws later. There is no indication that HPV vaccination rates improved in the year of, or after, enactment separate from the general trends. Such an effect would have been indicated by a sustained upward shift of the trend beginning at the “X.”

Figure 1. HPV Vaccine Initiation and Completion Rates Among Adolescent Girls by Year of Pharmacist Authority Law, NIS-Teen, 2008–2014.

a - States included in each group for girls: <=2008 - AL, AK, CA, CO, LA, MI, MO, NE, NV, ND, PA, SD, WA, WY; 2009 - AZ, GA, OK, TX; 2011 - AR, ID, KY, MS, OR; 2012 - UT; 2013 - DE, IL, IN, IA, WI; Never - CT, DC, FL, HI, KS, ME, MD, MA, MN, MT, NH, NJ, NM, NY, NC, OH, RI, SC, TN, VT, VA, W

Figure 2. HPV Vaccine Initiation and Completion Rates Among Adolescent Boys by Year of Pharmacist Authority Law, NIS-Teen, 2010–2014.

b - States included in each group for boys <=2010 - AL, AK, AZ, CA, CO, GA, LA, MI, MO, NE, NV, ND, OK, PA, SD, TX, WA, WY; 2011 - AR, ID, KY, MS, OR; 2012 - UT; 2013 - DE, IL, IN, IA, WI; Never - CT, DC, FL, HI, KS, ME, MD, MA, MN, MT, NH, NJ, NM, NY, NC, OH, RI, SC, TN, VT, VA, WV

The difference-in-difference analysis that categorized the pharmacist authority laws by type showed no statistically significant association between vaccination authority type and HPV vaccination (Table 2). This null result was found for girls and boys and for initiation and completion outcomes. The lack of statistical significance was a result of large standard errors (and therefore wide confidence intervals). Across specifications, HPV vaccination was more likely the older the adolescent, for Hispanics, the higher the engagement with the health care system (i.e., more visits, receipt of other vaccines), for Medicaid beneficiaries (except for completion among boys), for adolescents’ mothers with less than high school education (except for completion among girls), and for households with lower income.

Table 2.

Linear Probability Models of HPV Vaccination, NIS-Teen, 2008–2014

| Girls Initiation | Girls Completion | Boys Initiation | Boys Completion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Vaccination authority type | ||||||||

| No authority | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| Prescription only | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Protocol | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Independent authority | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| School entry requirements | ||||||||

| Tdap vaccination | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Meningococcal vaccination | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 13 years old | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| 14 years old | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.05* | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01 |

| 15 years old | 0.08* | 0.01 | 0.10* | 0.01 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.04* | 0.01 |

| 16 years old | 0.11* | 0.01 | 0.14* | 0.01 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.03* | 0.01 |

| 17 years old | 0.13* | 0.01 | 0.17* | 0.02 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.04* | 0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.04* | 0.01 | 0.04* | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Hispanic | 0.06* | 0.01 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.08* | 0.01 | 0.04* | 0.01 |

| Other or Unspecified | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Health care visits | 0.02* | 0.002 | 0.02* | 0.002 | 0.01* | 0.003 | 0.01* | 0.001 |

| Receipt of Influenza vaccine | 0.12* | 0.01 | 0.09* | 0.02 | 0.20* | 0.02 | 0.11* | 0.01 |

| Receipt of Tdap vaccine | 0.11* | 0.01 | 0.07* | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01 | −0.0005 | 0.01 |

| Receipt of meningococcal vaccine | 0.39* | 0.02 | 0.26* | 0.01 | 0.18* | 0.01 | 0.08* | 0.005 |

| Insurance | ||||||||

| Private | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| Medicaid | 0.07* | 0.01 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.06* | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Other public insurance | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Uninsured | −0.03* | 0.01 | −0.07* | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 |

| Unspecified or missing | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.001 | 0.02 |

| Parent characteristics | ||||||||

| Mother's education | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04* | 0.02 | 0.04* | 0.01 |

| High school diploma | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| Some college | −0.03* | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| College degree or higher | −0.04* | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Household characteristics | ||||||||

| Income | ||||||||

| Less than 25,000 | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| $25,001 – $50,000 | −0.05* | 0.01 | −0.04* | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| $50,001 – $75,000 | −0.06* | 0.01 | −0.04* | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 |

| $75,0000 or more | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 |

| Unspecified or missing | −0.05* | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05* | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 |

| Household size | −0.01* | 0.003 | −0.01* | 0.004 | −0.002 | 0.003 | −0.002 | 0.001 |

| Number of children | 0.01* | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.01* | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

indicates significance at the 95% confidence level. Note: Regressions also include indicator variables for state and year and state-specific time trends (i.e., interactions between state indicators and year as a continuous variable).

When pharmacist vaccination authority was collapsed into a single indicator for any type of law, there was still no significant association between the law and HPV vaccination (Appendix Table A1). Nor did the results change when adolescents from the 14 states that passed pharmacist vaccination authority laws prior to the analysis sample were added back to the sample (Appendix Table A1).

Appendix Table A1.

Alternative Linear Probability Models, NIS-Teen, 2008–2014

| Girls Initiation | Girls Completion | Boys Initiation | Boys Completion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Any Vaccination authority | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.003 | 0.01 |

| All States | ||||||||

| Vaccination authority type | ||||||||

| No authority | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| Prescription only | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Protocol | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.005 | 0.01 |

| Independent authority | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Any vaccination authority | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.005 | 0.01 |

indicates significance at the 95% confidence level. Note: Regressions also include all covariates in Table 2 and indicator variables for state and year and state-specific time trends (i.e., interactions between state indicators and year as a continuous variable).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the potential impact of state laws that allow pharmacist-administered HPV vaccination on national HPV vaccination coverage among adolescents. Our results suggest that, as currently implemented, these state laws were not associated with HPV vaccine coverage rates, regardless of the type of authority. There are several potential explanations for why we find no association between these laws and vaccine uptake, including the lack of financial incentive for pharmacists to administer HPV vaccine, poor promotion of adolescent vaccination services in pharmacies, and the possibility that families are merely substituting across settings from physician offices to pharmacies.

The largest structural barrier to pharmacists administering HPV vaccine is that many insurers do not consider pharmacies in-network providers for HPV vaccination.15,16 A pharmacy can bill insurance providers for vaccines administered to patients if the patients’ pharmacy benefits include vaccines or the insurance provider recognizes the pharmacy as a medical provider. Patients may have to pay out-of-pocket for vaccines from a pharmacy if their insurance does not cover pharmacy-delivered vaccines or their insurance provider considers the pharmacy out-of-network. The lack of recognition by insurance plans creates less incentive for pharmacists to stock HPV and other adolescent vaccines. A recent survey of state pharmacy association spokespersons showed that less than 25% of pharmacies routinely carried adolescent vaccines (defined as Tdap, HPV, meningococcal, and Hepatitis B vaccines), whereas over 50% routinely carried influenza vaccine, a commonly covered vaccine.17

Additionally, limited reimbursement through federal programs also hampers pharmacy involvement in HPV vaccination. The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides free vaccines to children who otherwise would not have the ability to pay for the vaccinations. This program is operated through each state’s health department and Medicaid program. Not all states recognize pharmacists as Medicaid providers, greatly limiting their participation in vaccination efforts for publicly insured children.18 Lack of participation by pharmacies in adolescent vaccination services for state-managed federal programs like VFC may, in part, explain why our analyses did not show a significant change in vaccine uptake after the passage of pharmacist authority laws during the study period. The NVAC recommends removing barriers to paying for HPV vaccines, including payment for vaccines provided outside of the medical home and by out-of-network or non-physician providers.19

Another explanation is the lack of promotion of the availability of HPV and other adolescent vaccines in pharmacies. Given the demonstrated success of adult vaccination in pharmacies,18 it is reasonable to think that similar approaches to increasing vaccine uptake would work for adolescents and their parents.20 Promotion of the advantages of pharmacy vaccination services, including longer and more convenient hours compared to traditional physician offices10 and no need for appointments16 may appeal to parents of vaccine-eligible adolescents. Many pharmacies already implement low-cost promotion strategies that could be adopted for HPV vaccine, such as advertising on interior and exterior store signage, receipts, and shopping bags.

One more explanation for the lack of association between vaccination rates and the pharmacist authority laws in our analysis is that the laws would have to encourage vaccination among adolescents who would have otherwise not received HPV vaccination. Families merely switching from vaccination in physician offices to pharmacies would not necessarily increase the overall uptake rate. The publicly available NIS-Teen does not contain information on the source of vaccine (e.g., pharmacies vs. medical clinics) and we are not aware of published studies on the use of pharmacies for vaccinations by children and adolescents. As such, we do not know the extent to which parents perceive pharmacies as viable venues for getting vaccines. Evidence suggests there may be benefits to pharmacist provision of vaccines apart from increasing the uptake rate; for example, pharmacist-delivered influenza vaccine is less costly relative to physician offices.21

In-pharmacy programs for adult vaccinations (e.g., influenza and shingles) could serve as a template for adolescent vaccines such as HPV. Currently, all 50 states and the District of Columbia, allow pharmacists to administer vaccines to adults. Data from the American Pharmacists Association showed that pharmacists provide adult vaccination services in 86% of community pharmacies, so pharmacists have an active role as vaccine providers in the U.S.22 However, this is not the case for HPV vaccination. State pharmacy practice laws, as currently implemented, underutilize the capacity of more than 250,000 trained pharmacists to administer vaccines and fully contribute to public health.23

This study has notable strengths, including a nationally representative sample from the NIS-Teen, provider-reported vaccinations to limit recall and self-reporting bias, the ability to examine different types of pharmacist authority laws, and an analytic design that accounts for state-specific time trends in HPV vaccination. However, our study is limited by several key factors. First, the estimated standard errors for the coefficients on the state laws were large. Therefore, we did not have enough statistical power to rule out relatively large effects of the laws. For example, the 95% confidence interval for the presence of any type of law on initiation among girls ranged from negative one percentage point to seven percentage points (author’s calculation from Appendix Table A1). Second, we did not have data on pharmacist reimbursement policy among state Medicaid programs and major insurers, which could moderate the effect of these laws on HPV vaccination. Finally, we could not include other patient-level factors known to affect HPV vaccination, such as the strength of physician recommendation to vaccinate.24–26

CONCLUSION

The passage of pharmacist authority laws is a necessary step to increase access to HPV vaccination but not sufficient on its own to increase HPV vaccine uptake among adolescents. Our study may provide a starting point for further research to identify key components enabling vaccination laws, and public health laws more generally, to be effective in practice. Of note, creating new reimbursement mechanisms could help sustain pharmacy vaccination programs and create an additional revenue sources for community pharmacies looking to expand their services. Additionally, strategic promotion of adolescent vaccinations in total, rather than HPV vaccine alone, during summer months when adolescent vaccine uptake is greatest, may also be important to increase parents’ awareness of the availability of vaccination services outside of the traditional medical home. While pharmacies are not intended to replace the medical home, they can play an integral role within the “immunization neighborhood” to meet the needs of patients and the communities served.23

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: WAC time was supported by NCI grant R25 CA116339 (Cancer Care Quality Training Program). PDS was partially supported by a National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Grant No. 5T32-HS000032).

Abbreviations

- ACIP

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- NIS-Teen

National Immunization Survey-Teen

- NVAC

National Vaccine Advisory Committee

- VFC

Vaccines for Children

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Conflict of Interest: Justin Trogdon and Paul Shafer have conducted research under contract with Merck, but this study was not supported by Merck. The other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Justin G. Trogdon, Email: justintrogdon@unc.edu.

Paul R. Shafer, Email: shaferp@live.unc.edu.

Parth D. Shah, Email: pdshah@email.unc.edu.

William A. Calo, Email: wacalo@live.unc.edu.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007–2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2013 - United States. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2013;62(29):591–595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males--Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2011;60(50):1705–1708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years - United States, 2014. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015;64(29):784–792. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6429a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher H, Trotter CL, Audrey S, MacDonald-Wallis K, Hickman M. Inequalities in the uptake of human papillomavirus vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of epidemiology. 2013;42(3):896–908. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA pediatrics. 2014;168(1):76–82. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health. Uptake: urgency for action to prevent cancer. A report to the President of the United States from the President’s Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drug Topics. [Accessed February 23, 2016];NACDS 2010–2011 Chain Pharmacy Industry Profile illustrates pharmacy value. http://drugtopics.modernmedicine.com/drugtopics/news/modernmedicine/modern-medicine-news/nacds-2010-2011-chain-pharmacy-industry-profile?page=full.

- 8.Spinnler M. [Accessed February 8, 2016];Pharmacists Provide Important Information adn Care During Cold and Flu Season. 2014 http://www.pharmacist.com/pharmacists-provide-important-information-and-care-during-cold-and-flu-season.

- 9.Brewer NT, Chung JK, Baker HM, Rothholz MC, Smith JS. Pharmacist authority to provide HPV vaccine: novel partners in cervical cancer prevention. Gynecologic oncology. 2014;132(Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goad JA, Taitel MS, Fensterheim LE, Cannon AE. Vaccinations administered during off-clinic hours at a national community pharmacy: implications for increasing patient access and convenience. Annals of family medicine. 2013;11(5):429–436. doi: 10.1370/afm.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robison SG. Impact of pharmacists providing immunizations on adolescent influenza immunization. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed February 23, 2016];National Immunization Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nis/data_files_teen.htm.

- 13.Immunization Action Coalition. [Accessed February 8, 2016];State Information: Meningococcal State Mandates for Elementary and Secondary Schools. 2015 http://www.immunize.org/laws/menin_sec.asp.

- 14.Immunization Action Coalition. [Accessed February 8, 2016];State Information: Tdap booster requirements for secondary schools. 2015 http://www.immunize.org/laws/tdap.asp.

- 15.Pilisuk T, Goad J, Backer H. Vaccination delivery by chain pharmacies in California: Results of a 2007 survey. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA. 2010;50(2):134–139. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah PD, Gilkey MB, Pepper JK, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Promising alternative settings for HPV vaccination of US adolescents. Expert review of vaccines. 2014;13(2):235–246. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2013.871204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skiles MP, Cai J, English A, Ford CA. Retail pharmacies and adolescent vaccination--an exploration of current issues. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2011;48(6):630–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bach A, Goad J. The role of community pharmacy-based vaccination in the USA: current practice and future directions. Integrated Pharmacy Research and Practice. 2015;4:67–77. doi: 10.2147/IPRP.S63822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overcoming Barriers to Low HPV Vaccine Uptake in the United States: Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: Approved by the National Vaccine Advisory Committee on June 9, 2015. Public health reports (Washington, DC: 1974) 2016;131(1):17–25. doi: 10.1177/003335491613100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dempsey AF, Zimet GD. Interventions to Improve Adolescent Vaccination: What May Work and What Still Needs to Be Tested. American journal of preventive medicine. 2015;49(6 Suppl 4):S445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prosser LA, O'Brien MA, Molinari NA, et al. Non-traditional settings for influenza vaccination of adults: costs and cost effectiveness. PharmacoEconomics. 2008;26(2):163–178. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Pharmacist Association. Annual Pharmacy-Based Influenza and Adult Immunization Survey 2013. Washington DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothholz M, Tan LL. Promoting the immunization neighborhood: Benefits and challenges of pharmacies as additional locations for HPV vaccination. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2016;12(6):1646–1648. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1175892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, Hall ME, Brewer NT. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2015;24(11):1673–1679. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider Communication about HPV Vaccination: A Systematic Review. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2016 doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1129090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.