Abstract

Purpose

To estimate medical costs attributable to venous thromboembolism among patients with active cancer.

Methods

In a population-based cohort study, we used Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) resources to identify all Olmsted County, MN residents with incident venous thromboembolism and active cancer over the 18-year period, 1988–2005 (n=374). One Olmsted County resident with active cancer without venous thromboembolism was matched to each case on age, sex, cancer diagnosis date, and duration of prior medical history. Subjects were followed forward in REP provider-linked billing data for standardized, inflation-adjusted direct medical costs from 1 year before index (venous thromboembolism event date or control matched date) to the earliest of death, emigration from Olmsted County, or December 31, 2011, with censoring on the shortest follow-up to ensure a similar follow-up duration for each case-control pair. We used generalized linear modeling to predict costs for cases and controls and bootstrapping methods to assess uncertainty and significance of mean adjusted cost differences. Outpatient drug costs were not included in our estimates.

Results

Adjusted mean predicted costs were 1.9-fold higher for cases ($49,351) than for controls ($26,529) (P=<0.001) from index to up to 5 years post-index. Cost differences between cases and controls were greatest within the first 3 months (mean difference=$13,504) and remained significantly higher from 3 months to 5 years post-index (mean difference=$12,939).

Conclusions

Venous thromboembolism -attributable costs among patients with active cancer contribute a substantial economic burden and are highest from index to 3 months but may persist for up to 5 years.

Keywords: Active Cancer, Cost analysis, Medical Care Utilization, Deep vein thrombosis, Pulmonary embolism, Venous thromboembolism, Cost of Illness

INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism is a common complication of active cancer.[1–3] Active cancer increases venous thromboembolism risk by 4- to 7-fold and accounts for nearly twenty percent of the entire venous thromboembolism burden occurring in the community.[4,5] In addition, patients with active cancer-associated incident venous thromboembolism are at increased risk for recurrent venous thromboembolism, and survival among cancer patients with incident and recurrent venous thromboembolism is significantly reduced.[7–9] Despite the well-established association between cancer and venous thromboembolism [10–13], there are few data assessing the economic burden of venous thromboembolism in active cancer patients.[14–18] Existing estimates of venous thromboembolism -associated costs among persons with cancer have largely focused on complications of anticoagulation therapy, increased length of hospitalization, and the high frequency of venous thromboembolism recurrence.[14,16–17] Moreover, venous thromboembolism case ascertainment almost always relied on discharge diagnosis codes obtained from billing or administrative claims data.[18] The limitations of discharge diagnosis codes for identifying incident venous thromboembolism are well recognized.[19–22] In addition, information on tumor stage and histologic subtype was not included.[18]

To address these limitations, we performed a population-based cohort study to estimate the medical costs attributable to venous thromboembolism in individuals with active cancer that included the entire spectrum of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism occurring in the community.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

Olmsted County, MN (2010 census population=144,248), provides a unique opportunity for investigating the natural history of venous thromboembolism.[25–27] Under auspices of the REP, Mayo Clinic, together with Olmsted Medical Center (OMC) (a second group practice), and their affiliated hospitals, provide over 95% of all medical care delivered to local residents, thereby linking the medical records for community residents at the individual level.[23, 28, 29] Using REP resources, we performed a cohort study to study cost attributable to venous thromboembolism among cancer patients. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and OMC Institutional Review Boards.

Study Population

All Olmsted County, MN residents with incident deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism over the 40-year period, 1966–2005, were identified as previously described.[25] Incident venous thromboembolism events were recorded by experienced nurse abstractors and were limited to persons residing in Olmsted County for whom this was a first life-time symptomatic venous thromboembolism.

The present study included all incident venous thromboembolism cases with active cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer). Active cancer had to have been documented in the 92 days (365/4, or about 3 months) prior to venous thromboembolism event date. Cancer was considered as inactive when the patient had undergone curative surgery or chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy with no evidence of residual disease. Myeloproliferative or myelodysplastic disorders, chronic myelocytic or lymphocytic leukemia, and hematopoietic growth factor therapy for these disorders were considered as always active cancer. For the few patients with multiple primary cancers, we used the cancer in the 92 days on or before the incident venous thromboembolism if one was before and one was after venous thromboembolism event. We used the more recent cancer if both were before the venous thromboembolism. If both primary cancers were diagnosed on the same day, a hematologist/oncologist (AAA) re-staged all cancer(s) and we used the cancer with the highest stage.

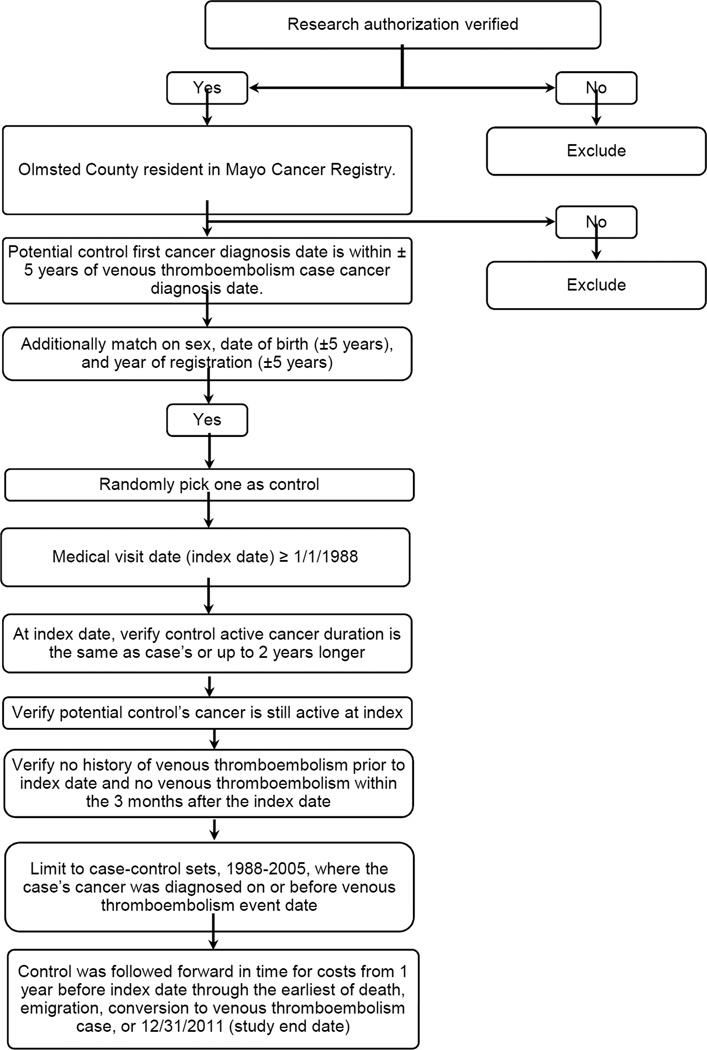

The Mayo Cancer Registry, available since 1972, includes patient demographics at cancer diagnosis and tumor classification using ICD-O 3rd edition, and also provides enumeration of the Olmsted County population with cancer from 1973 to present from which controls can be sampled.[23] After verifying consent to use of medical records for research and Olmsted County residency, the list of possible cancer controls for each venous thromboembolism case was subset to those Olmsted County residents with cancer whose first cancer diagnosis was within ± 5 years of the venous thromboembolism case’s cancer diagnosis (Figure 1).[26, 30] We further matched on sex, date of birth (± 5 years), and year of registration (± 5 years). Matching on year of registration assures a similar duration of medical records. For each case, the list of possible controls was randomly sorted and a control medical visit date after 1/1/1988 was chosen (index date). The control’s cancer was confirmed to be active within ± 3 months of the index date, and the duration of active cancer to be at least as long as or up to 2 years longer than the duration of active cancer of the case. Medical records were also reviewed to confirm no history of venous thromboembolism prior to or within 3 months after the index date.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram on the identification and selection of an Olmsted County, MN resident with active cancer and no venous thromboembolism (controls) matched to each Olmsted County resident with active cancer-associated incident venous thromboembolism, 1988–2005, on age, sex and duration of active cancer.

Collection of Medical Costs

Through an electronic data-sharing agreement between Mayo Clinic and OMC, patient-level administrative data on healthcare utilization and associated billed charges incurred at these institutions are shared and archived within the REP Cost Data Warehouse for use in approved research studies. Data are electronically linked, affording complete information on all hospital and ambulatory care delivered by these providers to area residents from January 1, 1987, through December 31, 2011. The REP Cost Data Warehouse includes information on all Olmsted County residents (i.e., both sexes, all ages, and all payer types, including the uninsured) and contains line-item detail on date, type, frequency, and billed charge for every good or service provided; long-term care, indirect, and outpatient pharmaceutical costs are not included. Recognizing discrepancies between billed charges and true resource use, the REP Cost Data Warehouse employs widely accepted valuation techniques to generate a standardized inflation-adjusted estimate of the costs of each service or procedure in constant dollars. Cost estimates in this study were adjusted to 2013 dollars.[32] Because cost data are only available electronically since 1987 and we wished to obtain costs in the year before index, the present study was limited to all Olmsted County case-control pairs whose index dates occurred between 1988 and 2005.[25,31] Each case and control was followed forward in time for costs from 1 year before their respective index date to earliest of death, emigration from Olmsted County, conversion to venous thromboembolism case (controls only), or December 31, 2011 (study end date). We ensured similar periods of observation for each case and matched control by censoring both members of each pair at the shortest length of follow-up for either member.

Pre-Index Comorbid Conditions

To compare index comorbidities between cases and controls, we obtained all International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses codes assigned to each individual in REP Cost Data Warehouse one year before index and categorized every diagnosis code assigned each individual into the 17 ICD-9-CM chapters and 114 subchapters. A summary measure of comorbid medical conditions in the year before index was also obtained using Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) System® software.[33] ACG software categorizes individual’s diagnosis codes into groupings based on persistence, severity, and etiology of the condition, as well as diagnostic certainty, and need for specialty care.[33] ACG software was used to assign a Resource Utilization Band (RUB) value to each individual. RUB categories are aggregations of ACGs that have similar expected resource use, with values ranging from 0 (no relevant diagnosis codes) to 5 (diagnosis codes associated with very high use).[34]

Statistical Analyses

Statistical testing used the 2-tailed alpha level of 0.05. The principal outcome was direct medical costs associated with venous thromboembolism. We adjusted for costs from 1 year before index, and analyzed costs from index to a maximum of 5 years post-index. For each subdivided post-index period, analyses were limited to those who were eligible for costs at the start of each interval. Post-index analyses were subdivided into: index-3 months, 3–6 months, 6-months-1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, 3–4 years, and 4–5 years. Models from post-index to 5 years and 3 months to 5 years included length of follow up from index. In initial analyses, the unadjusted costs for each control were subtracted from costs for its paired case in each time period; statistical significance was assessed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test to account for the highly skewed nature of cost data.[24,32,35–37] To isolate the costs attributable to venous thromboembolism, we used general linear multivariate modeling to examine the extent to which age, sex, RUB measure of pre-index comorbidity, cancer type (fourteen cancer types were compared to a reference group consisting of head and neck [2.3%], liver [1.2%], lung [12.8%], bone [0.1%], skin [1.9%], other genitourinary [0.3%], myeloproliferative syndromes [1.2%], myelodysplastic syndromes [0.1%], other [1.6%] and unknown 4 [0.5%] cancer types) and stage (continuous variable), and pre-index costs accounted for post-index cost differences between cases and controls. This adjusted approach employed 2-part models to account for zero costs[38,39] when appropriate, and incorporated a generalized linear model with family distribution based on the modified Park test recommended by Manning and Mullahy.[40] This analytic approach accounts for the skewed cost distribution while enabling coefficients to be directly back-transformed into the original dollar scale.[41,42] We analyzed differences in costs between cases and controls using the method of recycled predictions, setting all individuals as cases with venous thromboembolism or as controls without venous thromboembolism, while all other individual characteristics remain as observed.[43,44] Mean values and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the mean difference were calculated. Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics at index

We identified 374 venous thromboembolism cases and matched controls, both with active cancer. The mean ± SD (median; range) patient age for cases and controls was 65 ±15 (66; 2–96) and 65 ±15 (67; 1–95) years, respectively (p=0.72), and 48% of case/control pairs were female. The venous thromboembolism event type distribution was deep vein thrombosis alone (n=260; 70%), pulmonary embolism alone (n=83; 22%) and pulmonary embolism with deep vein thrombosis (n=31; 8%). The median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of follow-up post-index was 143 (43, 561) days and ranged from 1 day to 17 years. Cancer stage included those with cancer in situ (stage 0) to metastases (stage 4). Both the cancer type distribution and the cancer stage distribution differed significantly among cases and controls (p<0.001 for both; Table 1). In the year before index, significant differences between cases and controls were observed in 10 of 17 ICD-9-CM chapters (Table 2). The RUB summary measure of pre-index comorbidity also differed significantly for cases compared to controls (p<0.001). In the year before index, 59% (n=221) of cases had a RUB value indicative of very high resource utilization compared with 39% (n=145) of controls.

Table 1.

Cancer Type and Stage Distributions Among Olmsted County, MN with Active Cancer-Associated Incident Venous Thromboembolism, 1988–2005 (Cases), and Among Matched Olmsted County Residents with Active Cancer and No Venous Thromboembolism (Controls)

| Cancer Type and Stage | Cases (n=374) |

Controls (n=374) |

|---|---|---|

| ------------------------------- n (%) --------------------------- | ||

|

Cancer Type Brain |

15 (4.0) | 10 (2.7) |

| Lung | 61 (16.3) | 34 (9.1) |

| Stomach | 4 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Liver | 6 (1.6) | 3 (0.8) |

| Pancreas | 30 (8.0) | 10 (2.7) |

| Colon/rectal | 40 (10.7) | 29 (7.8) |

| Other digestive | 13 (3.5) | 6 (1.6) |

| Kidney | 6 (1.6) | 9 (2.4) |

| Bladder | 15 (4.0) | 4 (1.1) |

| Other genitourinary | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Leukemia | 18 (4.8) | 28 (7.5) |

| Lymphoma | 27 (7.2) | 26 (7.0) |

| Multiple myeloma | 4 (1.1) | 10 (2.7) |

| Myeloproliferative disorder | 9 (2.4) | 0 (0.) |

| Myelodysplastic disorder | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Bone | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Soft tissue/musculoskeletal | 4 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Skin | 5 (1.3) | 9 (2.4) |

| Other | 6 (1.6) | 10 (2.7) |

| Females, n=181 Breast |

40 (22.1) | 67 (37.0) |

| Ovary | 10 (5.5) | 10 (5.5) |

| Other gynecological | 15 (8.3) | 16 (8.8) |

| Males, n=193 Prostate |

39 (20.2) | 71 (36.8) |

|

Cancer Stage 0 |

21 (5.6) | 77 (20.6) |

| 1 | 61 (16.3) | 91 (24.3) |

| 2 | 69 (18.5) | 80 (21.4) |

| 3 | 81 (21.7) | 72 (19.3) |

| 4 | 142 (38.0) | 54 (14.4) |

Table 2.

Baseline Patient Characteristics and Comorbidities by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Code†

| Characteristics and Comorbidities | Case n (%) |

Control n (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| INFECTIOUS AND PARASITIC DISEASES (001–139) | 97(26) | 60 (16) | 0.001 |

| INTESTINAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001–009) | 15 (4) | 5 (1) | 0.039 |

| OTHER BACTERIAL DISEASES (030–041) | 34 (9) | 13 (3) | 0.002 |

| MYCOSES (110–118) | 45 (12) | 23 (6) | 0.007 |

| NEOPLASMS (140–239) | 367 (98) | 351 (94) | 0.004 |

| DIGESTIVE ORGANS AND PERITONEUM (150–159) | 95 (25) | 55 (15) | <0.001 |

| RESPIRATORY AND INTRATHORACIC ORGANS (160–165) | 67 (18) | 37 (10) | 0.002 |

| BONE,CONNECTIVE TISSUE,SKIN, AND BREAST (170–176) | 80 (21) | 107 (29) | 0.028 |

| OTHER AND UNSPECIFIED SITE (190–199) | 249 (67) | 184 (49) | <0.001 |

|

ENDOCRINE, NUTRITIONAL AND METABOLIC DISEASES, AND IMMUNITY DISORDERS (240–279) |

223 (60) | 169 (45) | <0.001 |

| OTHER METABOLIC AND IMMUNITY DISORDERS (270–279) | 185 (49) | 136 (36) | <0.001 |

| DISEASES OF THE BLOOD AND BLOOD-FORMING ORGANS (280–289) | 150 (40) | 100 (27) | <0.001 |

| MENTAL DISORDERS (290–319) | 112 (30) | 86 (23) | 0.038 |

| OTHER PSYCHOSES (295–299) | 32 (9) | 16 (4) | 0.024 |

| DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM (390–459) | 300 (80) | 216 (58) | <0.001 |

| DISEASES OF PULMONARY CIRCULATION (415–417) | 38 (10) | 5 (1) | <0.001 |

| OTHER FORMS OF HEART DISEASE (420–429) | 126 (34) | 90 (24) | 0.005 |

| DISEASES OF VEINS AND LYMPHATICS, AND OTHER DISEASES OF CIRCULATORY SYSTEM (451–459) |

188 (50) | 50 (13) | <0.001 |

| DISEASES OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM (460–519) | 198 (53) | 167 (45) | 0.028 |

| OTHER DISEASES OF THE UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT(470–478) | 49 (13) | 31 (8) | 0.044 |

| OTHER DISEASES OF RESPIRATORY SYSTEM (510–519) | 129 (34) | 78 (21) | <0.001 |

| DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM (520–579) | 230 (62) | 164 (44) | <0.001 |

| DISEASES OF ORAL CAVITY, SALIVARY GLANDS, AND JAW (520–529) | 59 (16) | 35 (9) | 0.011 |

| DISEASES OF ESOPHAGUS, STOMACH, AND DUODENUM (530–539) | 96 (26) | 62 (17) | 0.003 |

| NONINFECTIOUS ENTERITIS AND COLITIS (555–558) | 41 (11) | 22 (6) | 0.017 |

| OTHER DISEASES OF DIGESTIVE SYSTEM (570–579) | 85 (23) | 49 (13) | <0.001 |

| SYMPTOMS, SIGNS, AND ILL-DEFINED CONDITIONS (780–799) | 316 (84) | 289 (77) | 0.015 |

| SYMPTOMS (780–789) | 290 (78) | 237 (63) | <0.001 |

| ILL-DEFINED AND UNKNOWN CAUSES OF MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY (797– 799) |

160 (43) | 121 (32) | 0.004 |

| INJURY AND POISONING (800–999) | 196 (52) | 147 (39) | <0.001 |

| POISONING BY DRUGS, MEDICINAL AND BIOLOGICAL SUBSTANCES (960–979) | 57 (15) | 24 (6) | <0.001 |

| COMPLICATIONS OF SURGICAL AND MEDICAL CARE, NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED 996–999) |

97 (26) | 60 (16) | 0.001 |

ICD-9-CM chapters are capitalized and subchapter categories are indented. All venous thromboembolism ICD-9 codes were excluded.

Unadjusted cost comparisons

Unadjusted mean, median (IQR), minimum and maximum direct medical costs for case/control pairs and mean cost differences between case/control pairs from 1 year before index, all 5 years post-index and selected periods within the 5-years post-index interval are provided in the Supplementary Table. During the period index to 5 years post-index, three matched pairs had 1 member (1 case and 2 controls) who did not accrue any costs even though they were eligible for costs after their index date (alive and in Olmsted County) and so have zero costs. Three pairs (0.8%) did not incur costs due to zero costs in the first interval, index to 3 months. In the year before index, both mean and median costs for cases were slightly higher compared with controls. The unadjusted mean difference in pre-index annual costs between cases and controls was $17,915 (95% CI: $12,990–$23,538).

Adjusted cost comparisons

Adjusted mean predicted direct medical costs for cases and controls, and the adjusted predicted cost difference, for the overall time period index to 5-years, and for intervals within that period, are shown in Table 2. After adjusting for group differences in age at index, sex, costs incurred 1 year before index, cancer type and stage, and pre-index RUB values, the mean predicted costs for cases ($49,351) were significantly higher than those for controls ($26,529), with a mean predicted difference of $22,822 (bootstrapped 95% CI: $14,554–31,472), as compared to the unadjusted difference of $27,164. The adjusted mean cost was significantly higher for venous thromboembolism cases than controls for index to 3 months, and 6 months to 1 year post-index. For the time period 3 month to 5 years, the adjusted mean predicted cost for cases ($42,720) was significantly higher than that for controls ($29,781), with a mean predicted difference of $12,939 (bootstrapped 95%CI: $2,675–23,881).

To further explore potential causes for the observed difference in adjusted mean cost, we compared the distribution of post-index location of medical care (hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, emergency department and ambulatory setting) among cases and controls (Table 3). For time period index to 1 year, cases used significantly more hospital inpatient and emergency department care compared to controls, and marginally more hospital outpatient care. In contrast, controls used significantly more ambulatory setting care compared to cases, although the difference was only 7%.

Table 3.

Adjusted† Mean Direct Medical Costs Attributable to Cancer Associated Venous Thromboembolism Case/Control Pairs and Location of Medical Care by Time Period

| Time Period | Case/Control Pairs (n) |

Cases | Controls |

Mean Difference (Bootstrapped 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ------------------------------ $ ----------------------------- | ||||

| Index to 5 years | 374 | 49,351 | 26,529 | 22,822 (14,554, 31,472) |

| Index to 3 months | 374 | 22,733 | 9,229 | 13,504 (9,786, 17,757) |

| 3 to 6 months | 233 | 8,267 | 6,649 | 1,618 (−1,241, 4,208) |

| 6 months to 1 year | 173 | 14,803 | 9,446 | 5,357 (356, 10,458) |

| 1 to 2 years | 121 | 19,114 | 17,815 | 1,299 (−7,179, 11,051) |

| 2 to 3 years | 75 | 19,857 | 15,177 | 4,680 (−9,230, 20,834) |

| 3 to 4 years | 66 | 10,507 | 13,670 | −3,163 (−10,174, 3,719) |

| 4 to 5 years | 51 | 14,048 | 15,059 | −1,011 (−23,550, 13,357) |

| 3 months to 5 years | 233 | 42,720 | 29,781 | 12,939 (2,675, 23,881) |

| Time Period | Location of Medical Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | Emergency Department |

Ambulatory Setting |

||

| Inpatient | Outpatient | |||

| ---------------------------------------- % ----------------------------------------- | ||||

|

Index to 1 year Cases |

91 | 55 | 50 | 90 |

| Controls | 37 | 36 | 25 | 97 |

| p-value‡ | <0.001 | 0.07 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

Index to 3 months Cases |

87 | 46 | 41 | 89 |

| Controls | 25 | 24 | 17 | 97 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

3 to 6 months Cases |

29 | 29 | 20 | 91 |

| Controls | 16 | 21 | 11 | 82 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

6 months to 1 year Cases |

32 | 46 | 26 | 93 |

| Controls | 22 | 32 | 15 | 90 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Predicted costs are adjusted for age, sex, cancer type/stage, costs in the year prior to index and Resource Utilization Band values.

P-value from McNemar test

DISCUSSION

This population-based cohort study was conducted due to a shortage of reliable data regarding the extent to which cancer-associated venous thromboembolism contributes to excess medical costs and for how long any observed excess costs occur. The adjusted predicted mean direct medical costs were significantly higher for cases than for controls from index to 5-years post-index; the adjusted predicted mean cost for venous thromboembolism cases was 1.9-fold higher ($49,351) compared to controls ($26,529; mean difference=$22,822). Venous thromboembolism -attributable costs were highest for the period index to 3 months after index.

There are very few studies of venous thromboembolism -attributable costs among patients with active cancer. In a study of claims data from adult patients undergoing chemotherapy for selected common high-risk solid tumors (lung, colorectal, pancreatic, gastric, bladder, or ovarian), the all-cause total health care costs over a 12 month period among patients with a diagnosis code for venous thromboembolism and controls matched on cancer site and propensity score were $74,959 and $41,691, respectively (difference=$33,268).[18] Due to marked differences in study populations, data sources, methods and length of follow-up, the absolute difference in costs between cases and controls in this study cannot be compared to those in our study, but the costs are consistently higher for venous thromboembolism cases in both studies. Using methods similar to the present study, the costs of venous thromboembolism related to active cancer exceeded costs of venous thromboembolism related to hospitalization for major surgery but were less than costs of venous thromboembolism related to those hospitalized for acute medical illness.[45,46]

The observed increased costs for cases compared to controls within 5 years after index could reflect incremental costs for management of venous thromboembolism complications and venous thromboembolism recurrence. Over the full 5-year post-index time period, 92 (25%) of 374 cases had recurrent venous thromboembolism with a median time to recurrence of 76 days (IQR: 22.5 days-299 days). From index to 5 years post-index, the adjusted predicted mean cost for these 92 cases was $86,638 versus $38,835 for their matched controls (mean difference=$47,803: 95% CI: $23,236;$78,250). The adjusted predicted mean cost of the 282 cases without recurrent venous thromboembolism was $37,466 compared to $22,407 for their matched controls (mean difference $15,059: 95% CI: $8,637; $21,628). Survival after the active cancer-associated incident venous thromboembolism did not differ significantly among those with and without recurrent venous thromboembolism (log rank test p=0.22). In the year post index, cases differed significantly from controls in the distribution of location of medical care, with cases using significantly more hospital inpatient and emergency department care. Possible explanations include diagnosis and management of acute venous thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism complications, and differences in the management of cancer, cancer complications and comorbidities among cases and controls.

Our study has important limitations. The cost estimates are for a single geographic population which was 83% white in 2010. While no single geographic area is representative of all others, the under-representation of minorities may compromise the generalizability of our findings to different racial/ethnic groups. While costs associated with medications were not included in this analysis, the incremental costs of venous thromboembolism treatment likely would increase the cost difference between cases and controls. Cost estimates were limited to direct medical care costs and did not include indirect or long-term care costs. Finally, while we adjusted for age, sex, costs in the year prior to index, cancer type and stage, and RUB, we cannot exclude that some of the observed cost difference was due to incomplete adjustment for comorbidities and/or other unmeasured covariates.

In conclusion, venous thromboembolism contributes a substantial economic burden to patients with active cancer. Our findings will inform models that assess the cost-effectiveness of alternative interventions to reduce venous thromboembolism occurrence and guide reimbursement policy.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Significance.

Adjusted mean predicted venous thromboembolism-attributable costs among patients with active cancer from index to 5 years post index are substantial ($22,822; 95%CI: $14,554–31,472).

Venous thromboembolism-attributable costs were greatest within the 3 months after the event date (mean difference=$13,504) and remained significantly higher from 3 months to 5 years post-index (mean difference=$12,939).

Our findings will inform models that assess the cost-effectiveness of alternative interventions to reduce occurrence and guide reimbursement policy.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Catherine L. Brandel, R.N., Diadra H. Else, R.N., Jane A. Emerson, R.N., and Cynthia L. Nosek, R.N. for excellent data collection and Cynthia E. Regnier, R.N., as research project manager. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by grants from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute under Award Numbers R01HL66216 and K12HL83141 (a training grant in Vascular Medicine [KPC]) to JAH, and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Award Number R01AG034676 of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health). Research support also was provided by Mayo Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Noble S, Pasi J. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of cancer-associated thrombosis. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(Suppl 1):S2–S9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler CM. The link between cancer and venous thromboembolism: a review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32:S3–S7. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181b01b17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khorana AA, Connolly GC. Assessing risk of venous thromboembolism in the patient with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4839–4847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed) Chest. 2008;133:381S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorensen HT, Mellemkjaer L, Olsen JH, Baron JA. Prognosis of cancers associated with venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(25):1846–1850. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012213432504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levitan N, Dowlati A, Remick SC, et al. Rates of initial and recurrent thromboembolic disease among patients with malignancy versus those without malignancy. Risk analysis using Medicare claims data. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999;78:285–291. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Piccioli A, et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosis. Blood. 2002;100:3484–3488. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey D, Zhou H, White RH. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):458–464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prandoni P, Piccioli A, Girolami A. Cancer and venous thromboembolism: an overview. Haematologica. 1999;84(5):437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordstrom M, Lindblad B, Anderson H, Bergqvist D, Kjellstrom T. Deep venous thrombosis and occult malignancy: an epidemiological study. BMJ. 1994;308(6933):891–894. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6933.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Buller HR, et al. Deep-vein thrombosis and the incidence of subsequent symptomatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(16):1128–1133. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210153271604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cormack J. Phlegmasia alba dolens. In: Trousseau A, editor. Lectures on Clinical Medicine, Delivered at the Hotel-dieu, Paris. Philadelphia, PA: Lindsay & Blackiston; 1872. pp. 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elting LS, Escalante CP, Cooksley C, et al. Outcomes and cost of deep venous thrombosis among patients with cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1653–1661. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spyropoulos AC, Lin J. Direct medical costs of venous thromboembolism and subsequent hospital readmission rates: an administrative claims analysis from 30 managed care organizations. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13:475–486. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2007.13.6.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amin AN, Lin J, Yang G, et al. Are there any differences in the clinical and economic outcomes between US cancer patients receiving appropriate or inappropriate venous thromboembolism prophylaxis? J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:159–164. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0942002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington KJ, Bateman AR, Syrigos KN, et al. Cancer-related thromboembolic disease in patients with solid tumours: a retrospective analysis. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:669–673. doi: 10.1023/a:1008230706660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khorana AA, Dalal MR, Lin J, Connolly GC. Health care costs associated with venous thromboembolism in selected high-risk ambulatory patients with solid tumors undergoing chemotherapy in the United States. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:101–108. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S39964. Epub 2013 Feb 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hennessy DA, Quan H, Faris PD, Beck CA. Do coder characteristics influence validity of ICD-10 hospital discharge data? BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leibson CL, Needleman J, Buerhaus P, et al. Identifying in-hospital venous thromboembolism (VTE): a comparison of claims-based approaches with the Rochester Epidemiology Project venous thromboembolism cohort. Med Care. 2008;46:127–132. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181589b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White RH, Brickner LA, Scannell KA. ICD-9-CM codes poorly indentified venous thromboembolism during pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:985–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhan C, Battles J, Chiang YP, Hunt D. The validity of ICD-9-CM codes in identifying postoperative deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:326–331. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leibson CL, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Ransom J, O'Brien PC. Use and costs of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA. 2001;285:60–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heit JA, O'Fallon WM, Petterson TM, et al. Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(11):1245–1248. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809–815. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):585–593. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Feb;87(2):151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melton LJ., 3rd The threat to medical-records research. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(20):1466–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008 Mar;28(3):370–372. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.162545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leibson CL, Brown AW, Hall Long K, et al. Medical care costs associated with traumatic brain injury over the full spectrum of disease: a controlled population-based study. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(11):2038–2049. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health [computer program] 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health [computer program] 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leibson CL, Hu T, Brown RD, Hass SL, O'Fallon WM, Whisnant JP. Utilization of acute care services in the year before and after first stroke: A population-based study. Neurology. 1996;46(3):861–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leibson CL, Long KH, Maraganore DM, et al. Direct medical costs associated with Parkinson's disease: a population-based study. Mov Disord. 2006;21(11):1864–1871. doi: 10.1002/mds.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long KH, Rubio-Tapia A, Wagie AE, et al. The economics of coeliac disease: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(2):261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23(3):525–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newhouse JP, Manning WG, Morris CN, et al. Some interim results from a controlled trial of cost sharing in health insurance. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(25):1501–1507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112173052504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001 Jul;20(4):461–494. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Birnbaum HG, Ben-Hamadi R, Greenberg PE, Hsieh M, Tang J, Reygrobellet C. Determinants of direct cost differences among US employees with major depressive disorders using antidepressants. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(6):507–517. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200927060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullahy J. Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and the two-part model in health econometrics. J Health Econ. 1998 Jun;17(3):247–281. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basu A, Arondekar BV, Rathouz PJ. Scale of interest versus scale of estimation: comparing alternative estimators for the incremental costs of a comorbidity. Health Econ. 2006;15(10):1091–1107. doi: 10.1002/hec.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Esposito D, Bagchi AD, Verdier JM, Bencio DS, Kim MS. Medicaid beneficiaries with congestive heart failure: association of medication adherence with healthcare use and costs. Am J Manag Care. 2009 Jul;15(7):437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohoon KP, Leibson CL, Ransom JE, Ashrani AA, Petterson TM, Hall Long K, Bailey KR, Heit JA. Costs of Venous Thromboembolism Associated with Hospitalization for Medical Illness. Am J Manag Care. 2014 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohoon KP, Leibson CL, Ransom JE, Ashrani AA, Petterson TM, Hall Long K, Bailey KR, Heit JA. Direct Medical Costs Attributable to Venous Thromboembolism Among Persons Hospitalized for Major Surgery: A Population-based Longitudinal Study. Surgery. 2015;157:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.