Abstract

Context

Modifiable factors of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) are poorly described among children with advanced cancer. Symptom-distress may be an important factor for intervention.

Objectives

We aimed to describe patient-reported HRQOL and its relationship to symptom distress.

Methods

Prospective, longitudinal data from the multicenter Pediatric Quality of Life and Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) study included primarily patient-reported symptom-distress and HRQOL, measured at most weekly with the Memorial Symptoms Assessment Scale and Pediatric Quality of Life [PedsQL] inventory, respectively. Associations were evaluated using linear mixed-effects models adjusting for sex, age, cancer type, intervention arm, treatment intensity, and time since disease progression.

Results

Of 104 enrolled patients, 49% were female, 89% were white, and median age was 12.6 years. Nine hundred and twenty surveys were completed over nine months of follow-up (84% by patients). The median total PedsQL score was 74 (IQR 63–87) and was “poor/fair” (e.g., <70) 38% of the time. “Poor/fair” categories were highest in physical (53%) and school (48%) compared to emotional (24%) and social (16%) subscores. Thirteen of 24 symptoms were independently associated with reductions in overall or domain-specific HRQOL. Patients commonly reported distress from two or more symptoms, corresponding to larger HRQOL score reductions. Neither cancer type, time since progression, treatment intensity, sex, nor age was associated with HRQOL scores in multivariable models. Among 25 children completing surveys during the last 12 weeks of life, 11 distressing symptoms were associated with reductions in HRQOL.

Conclusion

Symptom-distress is strongly associated with HRQOL. Future research should determine whether alleviating distressing symptoms improves HRQOL in children with advanced cancer.

Keywords: Quality of life, pediatric cancer, palliative care, end of life, patient-reported outcomes, symptom distress

Introduction

Promoting patient-centered outcomes such as health-related quality of life (HRQOL) has become a priority in pediatric research and clinical care (1–9). This is particularly true for children with advanced cancer, where prior studies suggest a high degree of symptom-distress (10, 11). This distress, in turn, is associated with poor patient (12–14) and family (15, 16) outcomes. Furthermore, patient HRQOL is a key determinant of parent decision-making at the end of life, impacting participation in phase I clinical trials (17), use of artificial nutrition and hydration (18), and advance care planning (19, 20).

The construct of HRQOL reflects individual perceptions of the impact of illness on overall, physical, functional, emotional, social, and spiritual well-being (21, 22). In pediatric oncology, much of the literature to date has involved parent-proxy report (10, 23–29). Fewer studies have included the voice of the child (30–35). Likewise, prior studies have focused on survivors (26, 36) or patients receiving therapy for cancers which are expected to be cured (23, 25, 33); HRQOL in children with advanced cancer has seldom been described (37–39). Deeper knowledge about patient-reported HRQOL in this group is needed to alleviate suffering and promote patient (and family) well-being.

Three recent systematic reviews identified a wide array of variables associated with HRQOL in children with cancer (26, 36, 40). Factors consistently associated with poor HRQOL include concurrent cancer therapy (41–45), higher treatment-intensity (23, 46, 47), poor prognosis or history of relapse (23, 26), older age (25, 36, 40), cancer-type (where patients with sarcomas or brain tumors have poorer HRQOL) (36, 40, 45, 46), and female sex (23, 25, 40, 44). While existing results may help identify patients at risk for poor HRQOL (23), immediately modifiable factors of HRQOL, such as symptoms, have been insufficiently described (26, 36).

Using data from the Pediatric Quality of Life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) study (32), we aimed to describe: 1) prospectively collected patient-reported HRQOL among pediatric patients with advanced cancer; and 2) relationships between HRQOL, symptom distress, and demographic and medical factors. Based on the Wilson and Cleary HRQOL model (48), we hypothesized that greater symptom-distress would be associated with poorer HRQOL. If true, future interventions directed at recognizing and alleviating distressing symptoms could optimize clinical care and other patient-centered outcomes.

Methods

The present analyses use cohort data embedded in the PediQUEST trial (32). PediQUEST is a computer-based data system designed to capture patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and generate reports. Results from a pilot randomized clinical trial (RCT) testing the effect of using PediQUEST to provide PRO feedback to health care providers and families (intervention arm) compared to usual care (control arm) have been published previously (32).

Participants were recruited from three large pediatric cancer centers (Dana-Farber Boston Children’s Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Seattle Children’s Hospital) between December 2004 and June 2009, and were eligible if they were at least two years-old and had at least a two-week history of progressive, recurrent, or non-responsive cancer. Of 147 approached patients, 104 (70.3%) enrolled (32). Participants prospectively reported symptoms and HRQOL via the PediQUEST survey, which was administered through tablet computers during clinic or ward visits at most once weekly. For those not attending clinic, surveys were offered by phone once monthly. Participants received small non-monetary incentives (toys for younger children, gift cards for teenagers). Patients were followed until the time of death or the end of data collection. Institutional Review Boards at each site approved the study. Patients ages 18 years and older, and parents of children under 18 years, provided signed informed consent. All children under 18 years provided informed assent.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures

The PediQUEST-survey included the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL) (42), a well-validated measure of HRQOL, and the PediQUEST-Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (PQ-MSAS) (49), an adaptation of the child MSAS which measures symptom burden. A detailed description of the PediQUEST-survey has been presented elsewhere (32). Briefly, PedsQL is a 23-item HRQOL instrument with high internal consistency (≥0.88 for both patient and proxy report), with physical, emotional, social, and school domains (42). We used four age-appropriate versions (2–4, 5–7, 8–12, and 13–18 years old). Children may self-report from the age of five years. PQ-MSAS measures frequency, severity, and extent of bother from 24 physical and psychological symptoms with high internal consistency (>0.8). We used three age-appropriate versions (2–6, 7–12, 13–18 years old). Children may self-report from the age of seven, although the PQ-MSAS 7–12 is shorter (eight items) and complemented with parental report for the remaining 16 items.

For all ages, a PediQUEST-Survey consisted of a complete set of PedsQL and PQ-MSAS items. Only one respondent per tool (PedsQL or MSAS) was allowed, except for the PQ-MSAS 7–12 as explained above. Whenever possible, children were encouraged to self-report. If no self-report version was available (children younger than five years old), or if children declined to answer, the corresponding parent-proxy versions were used. Children older than eight years completed their surveys independently; those 5–7 years old were read the questions out loud by research staff (32). Whenever a child answered their age-appropriate version, we considered the whole survey a self-report. For example, a self-report of a 7-year-old would have child answers for PedsQL and PQ-MSAS 7–12 and parent answers for the remaining MSAS items. Equivalence across age-adapted versions and respondents was assumed.

Outcome of Interest: HRQOL (PedsQL Scores)

For each survey, PedsQL total score was calculated as the mean of the individual item scores; subscale scores reflected the means of physical, emotional, social, or school items respectively. Individual items were rated on a five-point Likert scale and scores transformed to a 0–100 scale (100 best) (42). The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for PedsQL is estimated to be 4.4 points for the total, and 6.6–9.0 for the subscale scores (50, 51). Mean total scores among children during and more than 12 months after therapy are 70.88 (standard deviation [SD] 17.19) and 77.66 (SD 15.25), respectively (42). School scores were calculated for all children regardless of their school attendance following author recommendations. However, to help interpretation, the survey also included a single question about recent school attendance. For graphical purposes, we categorized HRQOL scores a priori as poor (<40), fair (40–69.9), good (70–79.9) or very good/excellent (80–100) based on prior literature suggesting these thresholds discriminate clusters of patients with progressively impaired HRQOL (42, 50, 52, 53).

Main Covariate of Interest: High Symptom Distress

PQ-MSAS item response options used 0–4 categorical scales for adolescent and parent-proxy versions and 0–3 scales for the 7–12 year-olds version. Physical symptoms included: pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, anorexia, cough, diarrhea, vomiting, itching, skin issues, constipation, dysphagia, dry mouth, numbness, sweating, dyspnea, and dysuria; psychological symptoms included: irritability, sleep disturbance, nervousness, sadness, worrying, difficulty concentrating, and image issues. All symptom scores were transformed to 0–100 scales (100 worst) and then categorized as high symptom distress if the score was ≥ 33 for adolescent or parent-proxy versions, or ≥ 44 for 7–12 year-olds PQ-MSAS. These thresholds were defined a priori, as previously described, to represent scores that implied moderate to severe distress in at least one symptom domain (11).

Other Covariates

Clinical and demographic data were extracted from medical records, including age, sex, cancer type, date of diagnosis and date of death (where applicable). Disease status (e.g., progressive disease with dates) and cancer-directed treatment in the ten days prior to a PediQUEST administration (including dates, types of treatment, and corresponding procedures) also were extracted. As previously reported, cancer-directed treatment was classified according to its intensity: mild (oral or outpatient chemotherapy and/or minor procedures), moderate (inpatient intravenous chemotherapy, radiation alone or with oral chemotherapy, or major procedure), or intense (hematopoietic stem cell transplant conditioning, radiation therapy with intravenous chemotherapy, or surgery) (11).

Statistical Analyses

We report results on outcomes collected over nine months of follow-up. Variables were described according to their distribution. We assessed association between PedsQL scores and high symptom distress using linear mixed models including high symptom distress and other covariates as fixed effects, and patient as a random effect to account for repeated measures. In order to adjust for potential confounding, all models included sex, age (dichotomized as age ≥ 13 years), cancer-type, RCT intervention arm (PediQUEST intervention versus standard of care), time since last cancer progression (categorical variable), and intensity if treatment received in the ten days prior to the survey. We forward included symptom-distress by prevalence (11) and used the Akaike information criterion to define the final model. When exploring PedsQL school subscores, we ran a sensitivity analysis excluding the surveys of children who had missed school for more than two weeks; since results were unchanged, we report school subscores for all surveys where it could be calculated. In the subcohort of participants who completed surveys in the last 12 weeks of life (73 surveys from 25 children), we analyzed the relationship between HRQOL and individual symptom distress (including only those symptoms reported as distressing in at least 15 [>20% of] surveys) and adjusted only by treatment intensity and time since last progression because of sample size considerations. Given the exploratory nature of the study, we did not correct for multiple comparisons. We used a listwise approach to handle missing data because less than 2% of the surveys had incomplete information in PedsQL or PQ-MSAS scores. All analyses were performed with SAS Statistical Software, v. 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Full Cohort

Participant Characteristics

We have described response rates and child characteristics previously (11, 32, 54). Briefly, 104 of 147 approached children enrolled. Of those, 49% were female, most were non-Hispanic, white race, and the median age was 12.6 years (interquartile range [IQR] 7.9 – 17.1 (Table 1). Fifty-six percent had a non-central nervous system (CNS) solid tumor, 35% had a hematologic malignancy, and 10% a CNS tumor. At study entry, median times since diagnosis and most recent disease progression were 24 months (IQR 14–40) and three months (IQR 2–5), respectively. The characteristics of children who enrolled were similar to those who declined participation (54). For each enrolled child, a median of eight surveys were completed over nine months of follow-up, for a total of 920 PediQUEST surveys in the full cohort. Self-report rates were high: 84% of all respondents including 73% among 5–7 year-olds, 96% among 8–12 year-olds, and 99% among teenagers. In 64% of surveys, the reporting children had active disease. In 11%, they were hospitalized, and in 26% their disease had progressed in the 10 days prior to survey-completion. For 45% of surveys, children had been missing school for more than two weeks.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and the median number of corresponding PediQUEST surveys completed for each characteristic

| Child characteristic at the time of enrollment | Full cohort (N=104 children) |

Subgroup of children with end-of-life surveys (N=25 children) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n | %* | Median number of surveys per patient | n | % | Median number of surveys per patient | |

| Intervention arm | 53 | 51 | 8.0 | 16 | 64 | 4.0 |

| Control arm | 51 | 49 | 7.0 | 9 | 36 | 1.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Girls | 51 | 49 | 8.0 | 12 | 48 | 3.0 |

| Boys | 53 | 51 | 7.0 | 13 | 52 | 2.0 |

|

| ||||||

| White Race | 93 | 89 | 8.0 | 22 | 88 | 2.0 |

|

| ||||||

| < 13 years old | 54 | 52 | 8.0 | 12 | 48 | 2.5 |

| ≥ 13 years old | 50 | 48 | 8.0 | 13 | 52 | 2.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Hematologic Malignancy | 36 | 35 | 9.0 | 11 | 44 | 3.0 |

| Brain Tumor | 10 | 10 | 7.5 | 1 | 4 | 3.0 |

| Non Central Nervous System Solid tumor | 58 | 56 | 7.5 | 13 | 52 | 2.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Months since diagnosis (median, IQR) | 24 (14, 40) | – | 29 (21, 35) | – | ||

|

| ||||||

| Months since last progression prior to enrollment (median, IQR) | 3 (2, 5) | – | 4 (3, 6) | – | ||

Totals may not add up to 100% due to rounding. Full Cohort represents all children enrolled with surveys during first 9 months of follow-up; End of Life represents the subgroup of children within the full cohort that died during follow-up and completed surveys in their last 12 weeks of life.

HRQOL

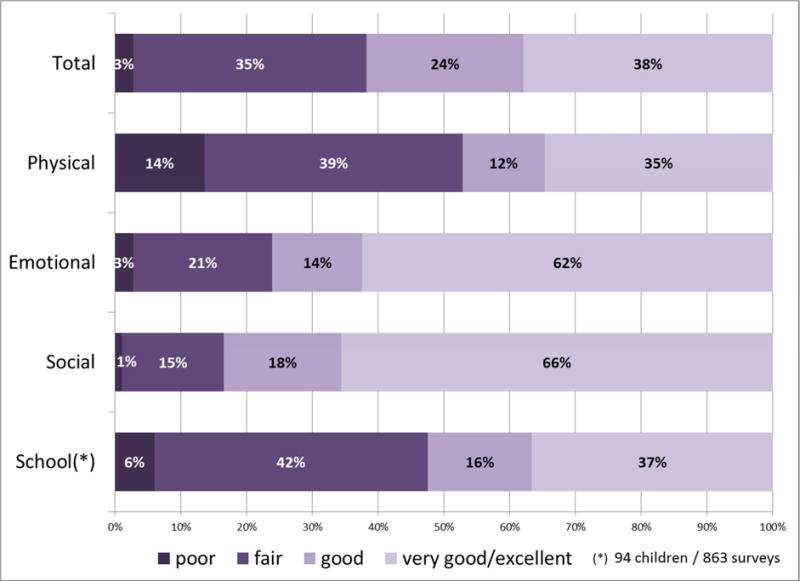

The median total PedsQL score was 74 (IQR 63–87 (Table 2). In 38% of surveys, the total score was below 70 and consequently categorized as “fair” or “poor” (Fig. 1A). The physical subscore ranked lowest (median 69 [IQR 50–88]); 53% of physical scores fell in the “poor/fair” categories. School subscores also were low, with 48% being “poor/fair”, while emotional and social subscores were only “poor/fair” in 24% and 16% of surveys, respectively.

Table 2.

Median PedsQL scores among patients in full cohort and the subgroup with end of life surveys.

| Cohort | PedsQL scale | N | Median Score | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Cohort (N=104 children, 920 surveys) | Total | 914 | 74 | 63 – 87 |

| Physical subscale | 915 | 69 | 50 – 88 | |

| Emotional subscale | 914 | 85 | 70 – 95 | |

| Social subscale | 914 | 85 | 75 – 100 | |

| School subscale | 863 | 70 | 55 – 90 | |

| End of Life Cohort (N=25 children, 73 surveys) | Total | 71 | 70 | 52 – 89 |

| Physical subscale | 71 | 56 | 31 – 91 | |

| Emotional subscale | 71 | 80 | 60 – 95 | |

| Social subscale | 71 | 90 | 80 – 100 | |

| School subscale | 68 | 75 | 50 – 93 |

Legend: PedsQL: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; IQR: inter-quartile range. Full Cohort represents all children enrolled with surveys during first 9 months of follow-up; End of Life Cohort represents the subgroup of children within the full cohort that died during follow-up and completed surveys in their last 12 weeks of life.

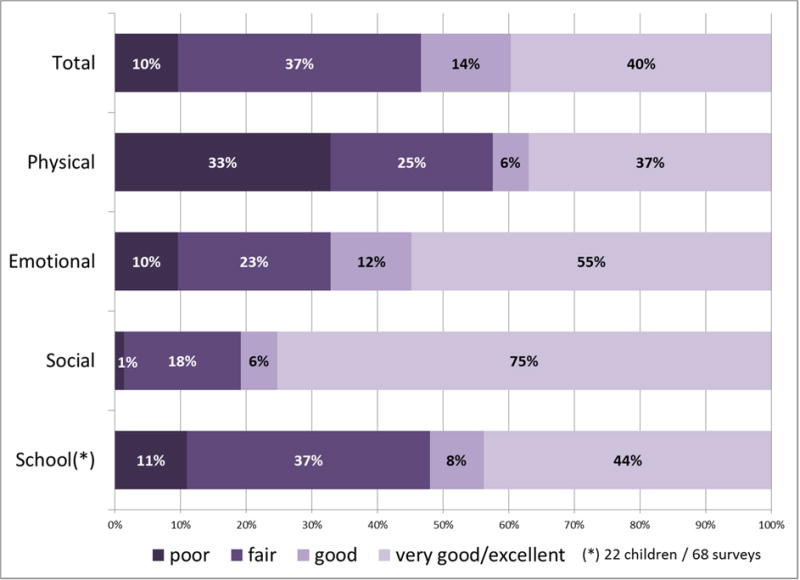

Fig. 1.

Distribution of HRQOL scores among enrolled patients. (A) Full cohort (all surveys (n=920), all children (n=104)); (B) Subgroup of children with end of life surveys (25 children, 73 surveys in the last 12 weeks of life).

Symptom Distress

Overall, participants reported a median of three (IQR 1–6) distressing symptoms per PediQUEST administration (11). As previously reported, symptom distress was not related to the intervention (11). In 73% (n=674) of the 920 surveys, participants simultaneously reported at least two distressing symptoms. In 35% (n=326), participants reported at least five, and in 12% (n=109), they reported at least nine distressing symptoms. Some symptoms were more likely to occur together. The highest correlation was observed between nausea and vomiting (Spearman correlation, r = 0.61); nervousness, worry and sadness (r > 0.45); and fatigue and drowsiness (r=0.39).

Multivariable Models

Distressing symptoms (both physical and emotional) were strongly associated with HRQOL scores (Table 3). After controlling for sex, age, cancer type, RCT arm, treatment intensity and time since disease progression, 13 distressing symptoms were independently associated with decreases in total and/or domain-specific HRQOL scores. Ten symptoms were associated with significant reductions in the total PedsQL score including difficulty concentrating, worrying, dry mouth, pain, sadness, irritability, insomnia, fatigue, vomiting, and anorexia. Difficulty concentrating and worrying were each associated with reductions ≥ MCID. Among subscales, several symptoms also were associated with reductions ≥ MCID. Specifically dry mouth and pain for PedsQL physical, and worrying, sleep disturbance and irritability for PedsQL emotional. Joint occurrence of these distressing symptoms was common in our study population. For example, children reported 2 of the 10 distressing symptoms associated with both PedsQL total and sub-scores in 165 (18%) of surveys. They reported 3 symptoms in 135 (15%), 4 in 86 (9%), and ≥5 in 105 (11%). The expected corresponding reduction in total PedsQL scores ranged between 4–9 points, 7–13 points, 10–16 points and 13–32 points when 2, 3, 4 or ≥5 distressing symptoms are concurrently reported by the child, respectively. For example, a patient reporting distress from both difficulty concentrating and worrying would be expected to have a total PedsQL score nine points lower than a patient not experiencing either distressing symptom. When ≥5 concurrent distressing symptoms were reported, the expected total PedsQL score would be between 13 and 32 points lower than for a patient not experiencing these symptoms.

Table 3.

Multivariate Models for full cohort: mean change in HRQOL score associated with moderate to severe distress from given symptom. N=920 surveys

| PedsQL Score | Distressing Symptom | Mean change in QOL score (95% CI) | p–value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | Difficulty concentratingɫ | −4.75 (−7.25, −2.24) | 0.0002 |

| Worryingɫ | −4.35 (−7.25, −2.24) | <.0001 | |

| Dry mouth | −3.94 (−6.98, −0.91) | 0.0109 | |

| Pain | −3.87 (−5.44, −2.30) | <.0001 | |

| Sadness | −3.75 (−5.96, −1.54) | 0.0009 | |

| Irritability | −3.40 (−5.96, −1.54) | 0.0036 | |

| Sleep disturbance | −3.27 (−5.36, −1.18) | 0.0021 | |

| Fatigue | −2.83 (−4.48, −1.19) | 0.0007 | |

| Vomiting | −2.03 (−3.89, −0.16) | 0.0337 | |

| Anorexia | −1.94 (−3.64, −0.24) | 0.0255 | |

| PHYSICAL | Dry mouthɫ | −7.46 (−12.54, −2.38) | 0.004 |

| Pain | −6.49 (−8.73, −4.25) | <.0001 | |

| Fatigue | −5.35 (−8.35, −2.36) | 0.0005 | |

| Difficulty concentrating | −4.95 (−8.63, −1.26) | 0.0085 | |

| Vomiting | −3.90 (−6.81, −0.99) | 0.0085 | |

| Worrying | −3.32 (−6.31, −0.33) | 0.0294 | |

| Irritability | −3.09 (−6.00, −0.17) | 0.0382 | |

| Anorexia | −3.07 (−5.86, −0.29) | 0.0305 | |

| EMOTIONAL | Worryingɫ | −14.55 (−18.26, −10.84) | <.0001 |

| Sleep disturbanceɫ | −10.75 (−13.58, −7.92) | <.0001 | |

| Irritability | −8.56 (−11.56, −5.57) | <.0001 | |

| Itching | −3.43 (−6.19, −0.67) | 0.015 | |

| Pain | −2.55 (−4.34, −0.77) | 0.0051 | |

| SOCIAL | Difficulty concentrating | −5.30 (−8.91, −1.68) | 0.0040 |

| Irritability | −4.25 (−6.56, −1.93) | 0.0003 | |

| Image issues | −3.95 (−6.92, −0.98) | 0.0092 | |

| Nervousness | −3.17 (−5.67, −0.68) | 0.0127 | |

| SCHOOL | Difficulty concentrating | −7.53 (−11.82, −3.24) | 0.0006 |

| Sleep disturbance | −5.18 (−8.40, −1.96) | 0.0016 | |

| Fatigue | −5.00 (−7.40, −2.60) | <.0001 | |

| Pain | −4.41 (−7.29, −1.53) | 0.0027 | |

| Sadness | −4.77 (−8.29, −1.26) | 0.0078 |

indicates symptoms for which the associated score reduction reached or was larger than the corresponding Minimal Clinically Important Differences (MCID).

MCID for PedsQL: Total score MCID 4.4; Physical sub-score MCID 6.7, Emotional sub-score MCID 8.9, Social sub-score MCID 8.4, School sub-score 9.1

Estimates and p-values obtained under linear mixed models including the set of symptoms distress, cancer type, time since last progression, sex, treatment intensity, age, and intervention arm as fixed effects and child as a random effect.

Neither cancer type, time since last progression, treatment intensity, sex, age, nor RCT arm were associated with HRQOL scores after the introduction of symptom distress in any multivariable models.

Subgroup of Children with End-of-Life PediQUEST Surveys

Participant Characteristics

Among children who died during the nine-month follow-up, PediQUEST surveys were completed for 25 children during the last 12 weeks of life. The distribution of age and sex in these children was similar to the full cohort; however only one had a brain tumor (Table 1). A median of three surveys were completed per child. Again, the rate of self-report was high: 79% of surveys were completed by the child, including 43% among 5–7 year-olds, 92% among 8–12 year-olds, and 98% among teens. Children had active disease for 81% of survey completions, and had disease progression in the 10 days prior to survey completion 48% of the time. For 55% of surveys, children had been missing school for more than two weeks.

HRQOL and Symptom Distress

In surveys completed during the last 12 weeks of life, the median PedsQL score was 70 (IQR 52–89 (Table 2). Forty-seven percent of total HRQOL scores were categorized as “poor/fair” (Fig. 1B). Physical and school subscores were worse, with 58% and 47% being “poor/fair,” respectively. Eleven symptoms (pain, fatigue, drowsiness, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea, irritability, vomiting, sadness, dry mouth, and worry) were reported as distressing in at least 15 surveys. All eleven were associated with significant decreases in one or more HRQOL scores (Table 4) in a mixed-model including the symptom, time since last progression and treatment intensity. Almost all significant score reductions were larger than the respective MCIDs.

Table 4.

Multivariate models for the subgroup of children with end-of-life surveys: mean change in HRQOL score associated with moderate to severe distress from given symptom. N=73 surveys.

| PedsQL Score | Distressing Symptom* | Mean change in QOL score (95% CI)** | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL score | Sadness | −15.02 (−26.07, −3.97) | 0.008 |

| Dry mouth | −12.05 (−21.03, −3.07) | 0.009 | |

| Anorexia | −11.22 (−21.65, −0.8) | 0.035 | |

| Irritability | −9.62 (−18.82, −0.42) | 0.040 | |

| Drowsiness | −9.37 (−17.42, −1.32) | 0.023 | |

| Pain | −6.63 (−13.01, −0.25) | 0.042 | |

| PHYSICAL score | Dry mouth | −18.93 (−33.5, −4.36) | 0.0109 |

| Anorexia | −18.04 (−32.74, −3.33) | 0.0162 | |

| Drowsiness | −15.33 (−23.5, −7.17) | 0.0002 | |

| Pain | −14.85 (−24.92, −4.78) | 0.0039 | |

| Diarrhea | −10.61 (−21.09, −0.13) | 0.0471 | |

| Vomiting | −9.67 (−18.22, −1.12) | 0.0267 | |

| Irritability | −7.78 (−13.64, −1.93) | 0.0091 | |

| Nausea | −7.2 (−12.64, −1.77) | 0.0094 | |

| EMOTIONAL score | Sadness | −28.03 (−42.89, −13.17) | 0.0002 |

| Worrying | −23.9 (−39.4, −8.4) | 0.0025 | |

| Irritability | −14.35 (−28.38, −0.32) | 0.0449 | |

| Drowsiness | −13.54 (−24.06, −3.03) | 0.0116 | |

| SOCIAL score | Irritability | −15.17 (−29.01, −1.34) | 0.0316 |

| Anorexia | −13.72 (−21.93, −5.51) | 0.0011 | |

| Dry mouth | −13.71 (−20.9, −6.53) | 0.0002 | |

| Fatigue | −11.76 (−22.27, −1.26) | 0.0282 | |

| Vomiting | −4.97 (−8.5, −1.45) | 0.0057 | |

| SCHOOL score | Dry mouth | −13.49 (−26.23, −0.74) | 0.0380 |

Eleven symptoms had distressful events in at least 15 surveys. Distressing symptoms listed if significantly associated with change in QOL score in a linear mixed model including the single distress-symptom, treatment intensity and time since last progression as fixed effects and child as random effect (p<0.05).

Minimal Clinically Important Differences (MCID) for PedsQL: Total score MCID 4.4; Physical sub-score MCID 6.7, Emotional sub-score MCID 8.9, Social sub-score MCID 8.4; Legend: QOL: Quality of Life; PedsQL: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0; CI: confidence interval

Discussion

The PediQUEST study is thus far the largest prospective cohort study of PROs among children with advanced cancer and includes a rare component of pediatric quality of life research: a high-degree of patient-report. Our findings address important gaps in pediatric oncology research and clinical care. We found that overall HRQOL in children with advanced cancer was similar to prior studies (51), even among children responding in the last 12 weeks of life. Importantly, however, we found that symptom distress was strongly associated with clinically meaningful reductions in HRQOL and that these associations were unchanged after adjustments for factors previously identified as potential determinants of HRQOL. Specifically, high distress from both physical symptoms such as pain, and emotional symptoms such as worrying or difficulty concentrating, spanned multiple HRQOL domains. Distress from comparatively rare symptoms such as dry mouth (11) also were associated with significant changes in HRQOL.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), Institute of Medicine, and Food and Drug Administration have all made understanding and improving patient-reported HRQOL a priority; knowledge of patients’ experiences, symptoms, physical function and psychosocial health enables tailored anticipatory counseling, clinical decision-making, and alleviation of distress (3, 55–57). This is particularly important in the setting of pediatric advanced cancer, where there may be equipoise about treatment efficacy, and HRQOL drives patient, parent, and provider decision-making (17–20).

Our findings suggest that intensive symptom management may improve HRQOL in children with advanced cancer. First, distressing physical and emotional symptoms were independently associated with reductions in patient-reported HRQOL in both the full and end-of-life cohorts. This was true regardless of symptom prevalence. Second, the presence of multiple concurrent distressing symptoms was common and had an additive effect on HRQOL scores. Third, although we are unable to determine the directionality of the association between symptom and HRQOL, the model proposed by Wilson and Cleary supports our hypothesis that symptom distress results in decreased HRQOL. Finally, none of the previously identified time-related factors of HRQOL included in our multivariable models (e.g., treatment intensity and time since progression) remained associated with patient-reported HRQOL scores after the introduction of symptom distress. Our findings also are consistent with studies of adolescents and young adults with cancer (ages 15–39), where current symptoms are independently associated with poorer HRQOL during initial cancer therapy (45). It follows that symptom distress may play an intermediary role in the relationships between previously identified covariates and HRQOL. For these reasons we suggest that interventions directly targeting symptom distress may help improve patient-reported HRQOL.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. Our analyses evaluated some known factors associated with HRQOL; however, we lacked the power or diversity to assess them all. For example, our sample included relatively few patients with CNS tumors, particularly in the end-of-life cohort. We also had relatively little racial or ethnic diversity in our sample and could not assess potential cultural differences in HRQOL. Importantly, poor child HRQOL has been associated with other unexamined factors such as socioeconomic status and parent physical and emotional health (23, 40, 44, 47, 58, 59).

Furthermore, results from the end-of-life cohort should be taken with caution. In this subgroup, the number of surveys per patient was limited and only a few were completed within the last month of life; sicker patients may be underrepresented. The sample size precluded adjustment for multiple concurrent distressing symptoms. This is important because we previously described high symptom-distress in this group (11), potentially contributing more significantly to HRQOL.

Finally, while a clear strength of our study is the high rate of child self-report, there is growing agreement that pediatric HRQOL research also should integrate the voice of parents (30, 60), and perhaps clinicians. We did not collect concurrent parent- or clinician-report because our overall aims were to determine if child-report would influence parent and provider awareness of child suffering and, in turn, inform clinical care. We only included parent-proxy reports when child report was unattainable. This pragmatic approach enabled a dataset of single and best-respondents per family. However, while concordance between child, parent, and clinician symptom report is generally poor (61), it is important to integrate parent and provider impressions because both impact medical decision-making. How and when to use combined PRO reports in clinical and research settings remains unclear (2, 30, 31, 51, 62).

These limitations are common in pediatric quality of life research (22). Additional challenges include barriers to data collection and study completion (34, 35), instrument selection, and interpretation of school HRQOL among children who may be absent from school (22, 54). To mitigate this issue, we screened children for school attendance and found no differences in mean scores based on school attendance. Additionally, patient enrollment and data collection was highly successful (54). The PedsQL instrument was chosen based on its widespread use in pediatrics (50), as well as its proven responsiveness, and construct and predictive validity (2, 22, 42, 63).

Conclusion

This analysis from the PediQUEST study showed that specific, targetable symptom distress is strongly associated with HRQOL, and generates hypotheses for future prospective research. For example, inquiring about specific distressing emotional symptoms and intensively treating all symptoms may improve multiple HRQOL domains. Larger cohort studies of pediatric patients at the end of life may better describe modifiable factors of HRQOL in this time period. We may not be able to alleviate all of the distress of patients and families facing life-threatening pediatric illness, but intensive symptom management presents one possibility for enhancing child and family well-being.

Acknowledgments

The PediQUEST study (Evaluation of Pediatric Quality of Life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology in Children with Cancer) was supported by grants NIH/NCI 1K07 CA096746-01, Charles H. Hood Foundation Child Health Research Award, and American Cancer Society Pilot and Exploratory Project Award in Palliative Care of Cancer Patients and Their Families. Dr. Rosenberg was supported by the grants NIH/NCATS KL2 TR000421 and NIH/NCI L40 CA170049. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors are grateful to families for their willingness to participate in the study; to Sarah Aldridge, CPNP-AC, CPHON, Lindsay Hoyt, ARNP, Janis Rice, MPH, Karen Carroll, BS, and Karina Bloom, BS, for their exceptional work on enrollment, data collection, and administrative support; to Bridget Neville, MPH for her assistance in data management and coding. Each named individual was compensated for his or her contribution as part of grant support. We thank the DFCI Clinical Research Informatics team led by Jomol Mathew, PhD, and members of the Pediatric Palliative Care Research Network for their dedicated efforts toward the completion of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01838564

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Solans M, Pane S, Estrada MD, et al. Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: a systematic review of generic and disease-specific instruments. Value Health. 2008;11:742–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Lane MM. Health-related quality of life measurement in pediatric clinical practice: an appraisal and precept for future research and application. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:34. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute-of-Medicine. Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute-of-Medicine. When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washinton, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobsen PB, Wagner LI. A new quality standard: the integration of psychosocial care into routine cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1154–159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American-Cancer-Society. Quality of life: American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network legistlative inititives. Washington, DC: ACS Cancer Action Network; 2013. Available from: http://www.acscan.org/content/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/2013-ACSCAN-Quality-of-Life-Legislation.pdf. Accessed January 28, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Definition of palliative care. Available from: http://who.int./cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed May 15, 2015.

- 8.Szilagyi PG, Schor EL. The health of children. Health Serv Res. 1998;33:1001–1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Academies of Sciences. Comprehensive cancer care for children and their families: Summary of a joint workshop by the Institute of Medicine and the American Cancer Society. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:326–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Symptoms and distress in children with advanced cancer: prospective patient-reported outcomes from the PediQUEST study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1928–1935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schrag NM, McKeown RE, Jackson KL, Cuffe SP, Neuberg RW. Stress-related mental disorders in childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:98–103. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, et al. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2396–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaudre G, Trocme N, Landman-Parker J, et al. Quality of life of adolescents surviving childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Arch Pediatr. 2005;12:1591–1599. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2005.07.017. [in French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, et al. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J of Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9162–9171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg AR, Baker KS, Syrjala K, Wolfe J. Systematic review of psychosocial morbidities among bereaved parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:503–512. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurer SH, Hinds PS, Spunt SL, et al. Decision making by parents of children with incurable cancer who opt for enrollment on a phase I trial compared with choosing a do not resuscitate/terminal care option. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3292–3298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rapoport A, Shaheed J, Newman C, Rugg M, Steele R. Parental perceptions of forgoing artificial nutrition and hydration during end-of-life care. Pediatrics. 2013;131:861–869. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, Wang J. Family-centered advance care planning for teens with cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:460–467. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9146–9154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC concept: Health-related quality of life. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hrHRQOL/concept.htm. Accessed May 29, 2015.

- 22.Anthony SJ, Selkirk E, Sung L, et al. Considering quality of life for children with cancer: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures and the development of a conceptual model. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:771–789. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0482-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sung L, Klaassen RJ, Dix D, et al. Identification of paediatric cancer patients with poor quality of life. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:82–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickard AS, Topfer LA, Feeny DH. A structured review of studies on health-related quality of life and economic evaluation in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:102–125. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sung L, Yanofsky R, Klaassen RJ, et al. Quality of life during active treatment for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1213–1220. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klassen AF, Anthony SJ, Khan A, Sung L, Klaassen R. Identifying determinants of quality of life of children with cancer and childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1275–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fakhry H, Goldenberg M, Sayer G, et al. Health-related quality of life in childhood cancer. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34:419–440. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31828c5fa6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jalmsell L, Kreicbergs U, Onelov E, Steineck G, Henter JI. Symptoms affecting children with malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1314–1320. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pritchard M, Burghen E, Srivastava DK, et al. Cancer-related symptoms most concerning to parents during the last week and last day of their child’s life. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1301–1309. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eiser C, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life and symptom reporting: similarities and differences between children and their parents. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:1299–1304. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell KM, Hudson M, Long A, Phipps S. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children with cancer: consistency and agreement between parent and child reports. Cancer. 2006;106:2267–2274. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, et al. Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1119–1126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell HR, Lu X, Myers RM, et al. Prospective, longitudinal assessment of quality of life in children from diagnosis to 3 months off treatment for standard risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results of Children’s Oncology Group study AALL0331. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:332–339. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitlow PG, Caparas M, Cullen P, et al. Strategies to improve success of pediatric cancer cooperative group quality of life studies: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1297–1301. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0855-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnston DL, Nagarajan R, Caparas M, et al. Reasons for non-completion of health related quality of life evaluations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macartney G, Harrison MB, VanDenKerkhof E, Stacey D, McCarthy P. Quality of life and symptoms in pediatric brain tumor survivors: a systematic review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2014;31:65–77. doi: 10.1177/1043454213520191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomlinson D, Hinds PS, Bartels U, Hendershot E, Sung L. Parent reports of quality of life for pediatric patients with cancer with no realistic chance of cure. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:639–645. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hechler T, Blankenburg M, Friedrichsdorf SJ, et al. Parents’ perspective on symptoms, quality of life, characteristics of death and end-of-life decisions for children dying from cancer. Klin Padiatr. 2008;220:166–174. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1065347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cataudella D, Morley TE, Nesin A, et al. Development of a quality of life instrument for children with advanced cancer: the pediatric advanced care quality of life scale (PAC-QoL) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1840–1845. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stokke J, Sung L, Gupta A, Lindberg A, Rosenberg A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of objective and subjective quality of life among pediatric, adolescent, and young adult bone tumor survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1616–1629. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawyer M, Antoniou G, Toogood I, Rice M. A comparison of parent and adolescent reports describing the health-related quality of life of adolescents treated for cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;12(Suppl):39–45. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<39::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer. 2002;94:2090–2106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward-Smith P, Hamlin J, Bartholomew J, Stegenga K. Quality of life among adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24:166–171. doi: 10.1177/1043454207299656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hinds PS, Nuss SL, Ruccione KS, et al. PROMIS pediatric measures in pediatric oncology: valid and clinically feasible indicators of patient-reported outcomes. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:402–408. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: the adolescent and young adult health outcomes and patient experience study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2136–2145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Landolt MA, Vollrath M, Niggli FK, Gnehm HE, Sennhauser FH. Health-related quality of life in children with newly diagnosed cancer: a one year follow-up study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barakat LP, Li Y, Hobbie WL, Ogle SK, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Psychooncology. 2015;24:804–811. doi: 10.1002/pon.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins JJ, Devine TD, Dick GS, et al. The measurement of symptoms in young children with cancer: the validation of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale in children aged 7–12. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:10–16. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3:329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:tpaapp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varni JW, Limbers C, Burwinkle TM. Literature review: health-related quality of life measurement in pediatric oncology: hearing the voices of the children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:1151–1163. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J, Chung H, Amtmann D, et al. Symptoms and quality of life indicators among children with chronic medical conditions. Disabil Health J. 2014;7:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang IC, Thompson LA, Chi YY, et al. The linkage between pediatric quality of life and health conditions: establishing clinically meaningful cutoff scores for the PedsQL. Value Health. 2009;12:773–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dussel V, Orellana L, Soto N, et al. Feasibility of conducting a palliative care randomized controlled trial in children with advanced cancer: assessment of the PediQUEST study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Institutes of Health. State-of-the-science conference statement. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 2002. Symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garcia SF, Cella D, Clauser SB, et al. Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: a patient-reported outcomes measurement information system initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5106–5112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamner T, Latzman RD, Latzman NE, Elkin TD, Majumdar S. Quality of life among pediatric patients with cancer: Contributions of time since diagnosis and parental chronic stress. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1232–1236. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brinksma A, Sanderman R, Roodbol PF, et al. Malnutrition is associated with worse health-related quality of life in children with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3043–3052. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2674-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varni JW, Thissen D, Stucky BD, et al. Item-level informant discrepancies between children and their parents on the PROMIS pediatric scales. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1921–1937. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0914-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hockenberry MJ, Hinds PS, Barrera P, et al. Three instruments to assess fatigue in children with cancer: the child, parent and staff perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:319–328. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00680-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eiser C, Morse R. Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:347–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1012253723272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Desai AD, Zhou C, Stanford S, et al. Validity and responsiveness of the pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL) 4.0 generic core scales in the pediatric inpatient setting. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:1114–1121. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]