Abstract

Type II translational research tends to emphasize getting evidence-based programs implemented in real world settings. To fully realize the aspirations of prevention scientists, we need a broader strategy for translating knowledge about human wellbeing into population-wide improvements in wellbeing. Far-reaching changes must occur in policies and cultural practices that affect the quality of family, school, workplace, and community environments. This paper describes a broad cultural movement, not unlike the tobacco control movement, that can make nurturing environments a fundamental priority of public policy and daily life, thereby enhancing human wellbeing far beyond anything achieved thus far.

Viewed broadly, the ultimate goal of prevention science is to assist societies in ensuring the social, psychological, and physical wellbeing of every member of society (Biglan & Embry, 2013; Wilson, Hayes, Biglan, & Embry, 2014). To achieve this, prevention scientists must expand the scope of strategies they develop, evaluate, and deploy. In particular, we must implement policies, practices, and media, in addition to programs so that we affect the prevalence of our most common and costly problems in entire populations. To do that, we need a comprehensive and empirically supported theory of human development and wellbeing.

The tobacco control movement provides a useful example of how to achieve a significant change in an entire population. Thanks to its success in the U.S., smoking prevalence has been reduced from 50% for men and 34% for women in 1965 to 23.5% for men and 17.9% for women in 2010 (CDC, 2011). The Institute of Medicine characterized this movement as “one of the 10 greatest achievements in public health in the 20th century” (IOM, 2007).

Elsewhere, I have enumerated the movement’s key features, which spurred unrivaled changes in the smoking culture (Biglan, 2015a). The effort included (a) surveillance to monitor smoking and its risk factors, (b) creative epidemiology to cleverly communicate smoking facts to policymakers and citizens and to expand understanding of the harm it causes, (c) advocacy for and implementation of policies that supported people changing their behavior and changed the norms and other environmental conditions supporting smoking, and (d) media campaigns.

The success of the tobacco control movement underscores the fact that disseminating programs is alone unlikely to have the impact on human wellbeing we desire. Early on, it became clear that, even though efficacious cessation programs existed, most people preferred quitting on their own. Thus, efforts shifted to motivating people to quit and supporting their efforts through clean indoor air policies, physician advice, nicotine replacement, and phone consultations (Lichtenstein, Zhu, & Tedeschi, 2010). Major changes came about in policies affecting indoor air, cigarette marketing, and taxation of tobacco products, thanks to carefully orchestrated advocacy and litigation (Biglan & Taylor, 2000). We need similar techniques to address the important public health problems we face, including obesity and antisocial behavior.

Toward a Comprehensive, Empirically Supported Theory of Human Wellbeing

Biologist E. O. Wilson has suggested the concept of consilience, the idea that evidence from different sciences can converge in understanding a phenomenon. David Sloan Wilson and colleagues (Wilson et al., 2014) presented an evolutionary framework for understanding human behavior and the intentional evolution of society toward greater human wellbeing that reflects such consilience. Below I review this framework.

Targeting Multiple Problems and the Environments That Produce Them

Tobacco control seems simple compared to prevention of the psychological, behavioral, and health problems endangering human wellbeing. Yet much evidence has converged over the past 50 years showing that common and costly psychological, behavioral, and health problems are inter-related and stem from the same environmental conditions (Biglan, 2015a; Biglan, Flay, Embry, & Sandler, 2012; Biglan, Brennan, Foster, & Holder, 2004). These facts point to the idea that we might prevent diverse problems by concentrating on creating environments that prevent multiple problems while cultivating prosocial behaviors to benefit society (Wilson, 2011). The possibility exists that we could organize a society-wide strategy that is more efficient than one might think given the seeming diversity of problems we face. The strategy would focus on the family, school, and community environments that are risk factors for multiple problems.

Kellam, Koretz, and Moscicki (1999) suggested organizing prevention around a life-course developmental perspective. Since then, evidence from developmental and clinical psychology, prevention science, and neuroscience has converged to pinpoint key aspects of child and adolescent functioning and their environmental influences. This has helped to identify numerous interventions with the potential to ensure that each child reaches adulthood with the skills, interests, habits, and values to live a productive life in caring relationships with others (National Research Council & IOM, 2009). Examples of that convergence include the IOM report, the Surgeon General report on young people’s tobacco use (USDHHS, 2012), and our recent proposal to unify human sciences within an evolutionary framework (Wilson et al., 2014).

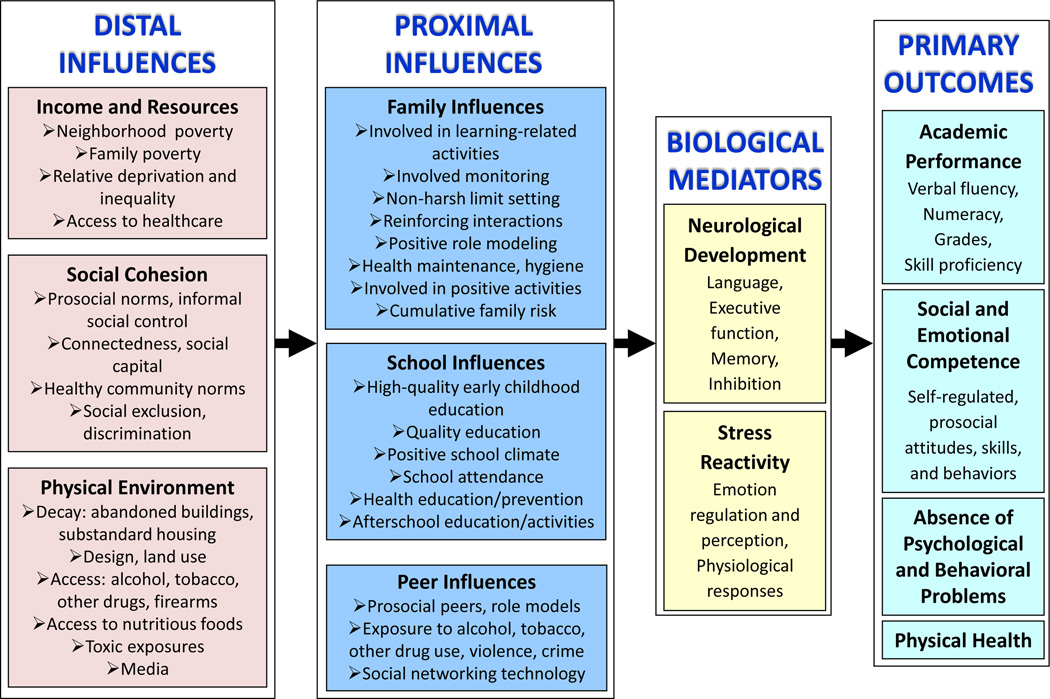

We have significant knowledge about social, biological, behavioral, and cognitive development from the prenatal period through young adulthood (Biglan et al., 2004; Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009) as well as the biological and social conditions that nurture or perturb development (Biglan, Flay, Embry, & Sandler, 2012). Figure 1 enumerates key developmental outcomes, the proximal and distal influences on them, and the biological substrata that mediate the relationship between environmental events and human functioning; the figure is adapted from Komro et al. (2011), which details the cognitive, social-emotional, and physical health outcomes at each phase and key costly psychological, behavioral, and health problems.

Figure 1.

The crucial features of effective preventive interventions can be characterized by the ways they make environments more nurturing. Biglan et al. (2012) analyzed risk and protective factor research, the results of randomized trials of interventions, and mediation analyses of the effects of these interventions to characterize generic features of nurturing environments. They: (1) reduce biologically and psychologically toxic conditions (e.g., conflict, coercion); (2) increase how much environments promote and richly reinforce prosocial behavior; (3) encourage families and schools to limit influences and opportunities for risky or problem behavior; and (4) promote psychological flexibility, which is the mindful, pragmatic pursuit of one’s values. This framework is elaborated in Biglan (2015a). It concurs with Stokols’ (1992) call to focus on environmental influences instead of strategies for changing individual behavior.

This framework suggests that in order to affect the prevalence of multiple problems among children and youth, we must increase the prevalence of nurturing families and schools. If this analysis is correct, it points to the need to consider not only the interventions that directly reach individual families and schools, but the larger context for families and schools.

The Larger Context Affecting Development

Poverty and economic inequality

Many researchers have documented poverty’s impact on child and adolescent development (e.g., Yoshikawa, Aber, Beardslee, 2012). It is clear that family poverty is a stressor that contributes to developing internalizing and externalizing problems (McLoyd, 1998). Family poverty during childhood is associated with an increased rate of mortality and cardiovascular disease in adulthood (Galobardes, Lynch, & Smith, 2004). A major pathway from poverty to later problems is through the disruptive impact poverty has on parenting, both as a stressor affecting parenting behavior (Conger, Patterson, & Ge, 1995; Eamon, 2001) and as an influence diminishing the time parents have with their children (e.g., Elder, Van Nguyen, & Caspi, 1995). Family interventions can benefit families living in poverty (e.g., Shaw, Dishion, Supple, Gardner, & Arnds, 2006) but poverty is a moderator that reduces the efficacy of family interventions (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Bradley, 2005).

Economic inequality is also a risk factor for developing psychological, behavioral, and health problems (Reiss, 2013; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). Inequality is associated with mental illness, obesity, academic failure, teenage births, homicides, imprisonment rates, social mobility, and lower life expectancy and lower levels of trust. The way that inequality leads to problems is not entirely clear, but inequality appears to be a risk factor independent of poverty. In countries with more inequality, disease rates are higher and longevity is shortened, even among affluent society members (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). Stress may underlie these effects, which may further increase for everyone when people of vastly different resources interact.

The U.S. has the highest rate of child poverty among economically developed nations, with over one-fifth of our children living in poverty (Gould & Wething, 2012). It also has the highest rate of economic inequality (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). Some evidence indicates that intervention may improve family economic wellbeing (Kitzman et al., 2000; Olds et al., 1997; Patterson, Forgatch, & DeGarmo, 2010). But in terms of affecting family economic security, we cannot rely on evidence-based programs alone. We also need to change policies that affect families’ economic security (Biglan, 2015b; Biglan & Cody, 2013; Hacker & Pierson, 2010).

Harmful marketing

Another influence increasing risks for children and adolescents is marketing of tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthful food (Biglan, 2011). Strong evidence, including experimental studies, shows the impact of cigarette marketing on teen motivation to smoke (Biglan, 2004; NCI, 2008). Evidence is not as strong regarding the impact of alcohol advertising on youth drinking and of marketing unhealthful foods to children. But in each case, correlational evidence suggests that youth exposure to marketing these products leads to greater consumption.

If such marketing increases unhealthful behavior, prevention scientists should target it as a risk factor. Here too, evidence points to the need for policy changes, such as the partial restrictions on cigarette marketing implemented in recent years (U.S. v. Phillip Morris et al., 2006). Traditionally, preventive efforts relevant to tobacco and alcohol have attempted to inoculate young people against the impact of harmful marketing (e.g., Biglan et al., 1987). No strong evidence attests to the benefits of these approaches. Scientists need to develop and test policies to restrict harmful marketing in the same way that policies regarding sanitation were developed when the role of sewage in infectious disease became clear (Johnson, 2006). Most lacking are studies of how to encourage adoption of effective policies.

This accumulated evidence can organize society-wide efforts to bring about dramatic reductions of society’s psychological, behavioral, and health problems. These efforts will undoubtedly benefit from widespread implementation of evidence-based programs, but the tobacco control movement shows that major changes require a mass movement in society that also advocates for significant policy changes and influences behavior through mass media.

Implementing and Evaluating Comprehensive Strategies

As communities, states, and nations implement efforts to improve population wellbeing across a broad range of psychological, behavioral, and health problems, it will be useful for prevention scientists to provide support for these efforts (e.g., Komro, O’Mara, & Wagenaar, 2012). That will include clear and reliable information about the programs, policies, and practices that support such efforts and provision of the most effective methodological and analytic tools. In this section, I outline some of the features that such an effort might have.

Surveillance Systems

Efforts to improve population wellbeing require accurate and timely data about the state of wellbeing (Mrazek, Biglan, & Hawkins, 2004). Having evidence about the rates of key problems provides leverage in influencing policymakers and citizens to support efforts to affect problems. Imagine if communities had annual report cards on child wellbeing and family and school conditions. They could help to justify implementing interventions. Communities could tell if their efforts were bringing about change. Improvements would strengthen support for interventions. Lack of evidence of improvement would motivate modification of interventions.

The analysis presented above suggests that communities should collect, at a minimum, data on the prevalence of the most common and costly psychological, behavioral, and health problems. If the quality of school and family environments affect these problems, the ideal surveillance system would provide estimates of the prevalence of nurturing families and schools. Such systems can enhance capacity building, empowerment, leadership, and community sustainability.

Systems to monitor wellbeing are in increasing use, but not every community estimates its population’s wellbeing. It may seem unlikely that such systems will ever be widely used. But most developed countries have monitored key economic indicators for many years. The Society for Prevention Research has advocated for these systems (Mrazek et al., 2004) and SAMHSA funds states to develop them (SAMHSA, 2014). But a federal law to fund them would be helpful.

As communities initiate these systems, experimental analyses of change efforts can occur (e.g., repeated measures of the incidence and prevalence of psychological and behavioral problems would enable testing of an intervention’s impact across multiple communities (Biglan, Ary, & Wagenaar, 2000; Gottfredson et al., 2015). Besides ongoing surveillance of public health outcomes, research on the incidence and prevalence of social indicators and their relationship to public health outcomes may influence public understanding and policymaking (e.g., Abramowitz & Albrecht, 2013; Cardosos, 2005; Jorda & Sarabia, 2015; Sharma & Sharma, 2010).

Programs

The most common scenario for how prevention science will contribute to population change seems to be that evidence-based programs will be widely implemented with fidelity and effectiveness. There is certainly empirical evidence for many family and school interventions (Biglan, 2015a; NRC & IOM, 2009) and some comprehensive community interventions (e.g., Feinberg, Jones, Greenberg, Osgood, & Bontempo, 2010; Jonkman et al., 2009; Spoth, Guyll, Redmond, Greenberg, & Feinberg, 2011).

The evidential basis for programs

Flay et al. (2005) and Gottfredson et al. (2015) provide sound guidelines to identify evidence-based programs. The hope is to influence policymakers and practitioners to adopt the most promising ones. The standards also increase the quality of empirical work on programs. Both sets of standards call for multiple RCTs to establish an intervention’s efficacy and trials to assess its effectiveness across diverse populations and settings or when delivered by non-research personnel. The newer standards emphasize theoretically driven studies to test the theory by analyzing mediation of effects via their impact on certain mediating processes. This can improve our understanding of precisely how environmental changes affect development.

A caution

Evaluating preventive interventions through randomized trials has been the most important methodological factor in accumulating efficacious and effective interventions. The attention to the details of the methods used in these studies has gradually improved the studies’ rigor and our confidence in them. Examples include recognizing the problem of intraclass correlations in group randomized trials and adopting appropriate design and analytic methods (Murray, 1998; Baldwin, Murray, & Shadish, 2005), the need for replication (e.g., Valentine et al., 2011), the distinction between efficacy and effectiveness trials (Flay, 1986), and recent attention to the greater effect sizes found when program developers evaluate them than when independent researchers do so (Lexchin, Bero, Djulbegovic, & Clark, 2003; Petrosino & Soydan, 2005). Improvements in assessing interventions will undoubtedly continue to evolve.

A question that prevention scientists frequently ask is, “When is the evidence ‘good enough’ to justify dissemination?” Prevention scientists often advocate that we be cautious (e.g., by requiring at least two randomized trials by independent evaluators; Flay et al., 2005) before widely implementing a program. Such a standard would prevent implementation of programs that are unlikely to improve outcomes. However, an alternative strategy, which characterizes much public policy, is to implement programs that offer any evidence of effectiveness.

What I believe is essential, but currently far from standard, is ongoing evaluation of all programs, whether they have survived multiple tests via randomized trials or none. For example, an intervention shown to produce certain outcomes in an RCT should undergo continual monitoring to ensure it produces the expected outcomes. One may not be able to do this through further randomized trials (although Forgatch, Patterson, and DeGarmo, 2005, did this in their implementation of Parent Management Training, Oregon in Norway). However, one can and should assess all outcomes using the same measures used in the original evaluation. One could assess if the changes from pre- to post-treatment and follow-up approximated the results for the intervention condition in the original studies, using non-inferiority or equivalence methods to assess if the intervention achieves outcomes similar to those from the randomized trials (D'Agostino, Massaro, & Sullivan, 2003; Greene, Morland, Durkalski, & Frueh, 2008).

Increasingly states, provinces, and communities assess the wellbeing of children and adolescents in ways that would allow us to monitor the impact of programs currently in place. For example, Oregon is implementing a system that assesses incoming kindergartners for their cognitive and social readiness. And, measures of even younger children are in development: eventually every county will have data on whether children at ages 2, 3, and 4 are progressing sufficiently to be ready for kindergarten. Other states are getting data on the psychological and behavioral problems of adolescents that allow the evaluation of prevention efforts in middle and high schools.

In sum, although we should continue to push for RCTs of programs, they can take place in the “real world” as valid measures of functioning become widely adopted. As Gottfredson et al. (2015) suggest, the second evaluation of a program could occur in the service system rather than in more pristine lab conditions. Doing this will hasten the spread of effective programs while requiring that developed programs are ready to implement in the existing service system.

The larger empirical context for evaluating a given program

Another factor to consider when determining if a program is ready to disseminate is the context of empirical support for similar programs. With family interventions, a number of them have shown effects on child and adolescent behavior through essentially the same behavioral methods. Table 1 lists several family interventions evaluated in multiple randomized trials. The studies vary but each is grounded in a behavioral analysis of the contingencies involved in parent-child interactions. Each does at least three of the four things listed. All reduce coercive interactions (Dishion & Snyder, 2004) between parents and children and increase positively reinforcing interactions between them. They all encourage parents to listen to their children, follow their lead, or otherwise increase the degree to which they communicate with their children in caring and respectful ways. All encourage parents to monitor what their children do and set limits on their behavior so they are less likely to be tempted to engage in risky or problematic behavior.

Table 1.

A sample of evidence-based family interventions

| Program | Reduction of coercive interactions |

Positive reinforcement for prosocial behavior |

Parents listening, following children’s lead, communicating |

Monitoring and limit setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Check-Up (Shaw et al., 2006) | X | X | X | |

| Family Therapy (Nichols & Schwartz, 1998) | X | X | X | |

| Incredible Years (Webster-Stratton & Mihalic, 2001) | X | X | ||

| Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (Fisher & Chamberlain, 2000) | X | X | X | |

| Multisystemic Therapy (Henggeler, Clingempeel, Brondino, & Pickrel, 2002) | X | X | X | |

| Nurse Family Partnership (Olds, 2005) | X | |||

| Parent Management Training, Oregon (Forgatch et al., 2005) | X | X | X | X |

| Triple P (Sanders, 1999) | X | X | X |

This body of evidence is relevant for evaluating any program. The fact that these methods have proven effective in multiple studies, by multiple investigators, using similar components should increase our confidence in any program. I fear that evaluating one program in isolation from consideration of the larger body of evidence will make us too cautious about implementing each program. If we evaluate each program separately and urge caution in implementing any one based solely on that program’s evidence we run the risk of reducing public support for policies that would increase the availability of programs for every family that could benefit while continuing the use of never-evaluated programs. And that makes it more likely that governments and philanthropic organizations will continue to fund programs for which there is little or no empirical evidence. Having said this, however, I would reiterate that it is essential to obtain ongoing evidence about the impact of any program when it is implemented in the “real world.”

Kernels: Evidence-Based Behavior-Influence Practices

Prevention scientists’ thinking about how to influence community and societal transformation should include disseminating simple behavior influence techniques (e.g., time out, praise notes, and transition cues) to reliably influence behavior. Embry and Biglan (2008) identified over 50 such techniques, nicknamed “kernels.” Kernels are not programs: they consist of one component. They have the potential to be widely used to support and promote nurturing.

Policies

Prevention science and practice lean toward emphasizing program development, evaluation, and dissemination. Yet a case can be made that public policy will ultimately be more important in realizing societies where most people thrive. Above I described the harm of poverty, economic inequality, and some forms of corporate marketing (Biglan, 2011; Biglan, 2015a; Biglan & Cody, 2013; Biglan & Embry, 2013). Programs may mitigate some harm from these conditions but it seems more likely we will have large population-level effects through policies restricting harmful marketing practices and reducing poverty and inequality (Biglan, 2015.

Komro, Tobler, Delisle, O’Mara, and Wagenaar (2013) provide an extensive review of policies that can benefit children’s development. They identified 98 policy-relevant community interventions, 46 of which they believe meet scientific efficacy criteria.

Policies to reduce poverty and inequality include (a) changing tax structures, (b) increasing the minimum wage and indexing it to inflation, (c) subsidizing housing, (d) providing healthcare, (e) increasing the availability and generosity of the earned income tax credit, and (f) increasing the level and length of unemployment insurance (Hacker & Pierson, 2010; Hacker, Pierson, & Moyers, 2012; Komro et al., 2012). Public policy affects poverty by affecting the economy: deregulating banking led to investment practices that led to the great recession of 2008 (McLean & Nocera, 2010; Warren, 2014), which caused massive unemployment. Reeves et al. (2012) found that U.S. suicide rates increased significantly between 2008 and 2010 compared to the prior eight years, a rise they attributed to the economic conditions.

Wagenaar and Burris (2014) edited a volume on the law and public health. They stress the importance of studying the impact of policies on health and describe a framework to guide such research. In light of poverty’s impact on wellbeing, it is vital that prevention scientists expand research in this area. We must not only delineate harmful and beneficial policies but also conduct research on how to change policies. As governmental laws and regulations affect human wellbeing and since we have evidence as to which policies are beneficial (Wagenaar & Burris, 2014), it is surprising how little we know about how to get evidence-based policies adopted.

Media

Considering their potential to affect whole populations, the media’s impact on prevention receives less attention than it should. Abroms and Maibach (2008) reviewed evidence that media campaigns affect people at three levels (individual, social network, and community) and affect the physical and social structure of environments both locally and distally. They indicate that meta-analyses of media’s impact on individuals show that media campaigns can have a small impact on people’s behavior, but considering the size of the effect, we should keep in mind that a small effect in a population can translate into a very significant impact on public health. There is also evidence that media campaigns aimed at members of an individual’s social network can affect behaviors like smoking, drinking, and having unprotected sex. These campaigns try to stimulate interactions among social group members to change norms and influence behavior.

Media advocacy to affect public policy is particularly important, given its impact on public health. Abroms and Maibach (2008) cite studies of some policy impact (e.g., policies on store display of tobacco products). They conclude that the evidence base for the efficacy of media advocacy is “surprisingly thin” and encourage strategies to evaluate such efforts.

Empirical Evaluation

The ultimate proof of a comprehensive effort to increase nurturance in families and schools and prevent multiple problems will come from evidence that nurturance increases and multiple problems decline. We know the optimal way to evaluate these efforts is by rigorous experimental evaluations. There is ample precedent for RCTs evaluating comprehensive community interventions (Arthur, Hawkins, Pollard, Catalano, & Baglioni, 2002; Hawkins, Oesterle, Brown, Abbott, & Catalano, 2014; Spoth & Greenberg, 2011). The obstacles are the size and cost of such trials. Given the potential of such trials to document significant reductions of multiple problems in entire populations, such research should be a high priority for policymakers. Unfortunately, despite valuable advocacy for such research (Baron, 2007), substantial funding seems unlikely to appear in the near future (McElwee, 2013).

Interrupted time series designs, requiring fewer communities, provide experimental evidence of the impact of a comprehensive intervention (Biglan et al., 2000). A multiple baseline design implementing the intervention in one community at a time would enable assessing if change in the level of nurturance and multiple problems occurred only when a community implemented the intervention. Ideally, this design would have at least three communities, would randomly choose the sequence of communities to receive the intervention, and would have enough time between implementations so the intervention could influence targeted outcomes. Even absent these optimal conditions, there could be considerable value in having multiple communities receiving repeated measures of these outcomes and implementing comprehensive interventions. Certainly, “natural experiments,” in which a policy is implemented in one jurisdiction and its impact observed on a repeated measure has pinpointed the value of many policies (e.g., Wagenaar & Burris, 2013; Wagenaar, Maldonado-Molina, & Wagenaar, 2009).

In this context, we can see the importance of a surveillance system. To the extent that states or communities measure the degree to which its families and schools are nurturing and the prevalence of its psychological and behavioral problems, they can determine if these vital signs of human wellbeing are changing in the right or wrong direction. Keep in mind that the tobacco control movement progressed via annual data on (a) smoking prevalence, (b) the incidence of youth beginning to smoke, (c) the extent of key influences on smoking, and (d) implementation of antitobacco policies. It is true that some tobacco control efforts underwent evaluation in experimental designs (e.g., Biglan, Ary, Smolkowski, Duncan, & Black, 2000). But the tobacco control movement benefited from evidence that policies, programs, and media helped to lower levels of smoking in specific places. As every jurisdiction obtained data on smoking behavior, through an evolutionary process of variation and selection (Mrazek et al., 2004), it could discern what worked in one jurisdiction and implement it in other jurisdictions while abandoning efforts that seemed to have little impact.

Conclusion

Prevention scientist would do well to consider whether their boldest aspirations are more likely to be realized if we expand our attention to the full range of programs, practices, policies, and media needed to bring about significant change in the wellbeing of entire populations. Much of our history involves research on risk and protective factors and on preventing individual problems (e.g., substance abuse, antisocial behavior). This work has converged to show inter-relationships among problems and the value of interventions that make families, schools, and communities more nurturing. We thus have ample reason to focus on how to increase the prevalence of nurturance in these environments. Many interventions already help to do this; after all the concept of nurturance arose through analyzing these interventions (Biglan, 2015a; Biglan et al., 2012). But to influence nurturance effectively and efficiently in the population, we must expand the breadth of our change efforts and develop strategies equal to the task.

We can help communities and states increase their already growing prevention efforts. They will benefit from the support of prevention scientists who have the knowledge and skill to help implement evidence-based interventions and evaluate their impact in real-world settings (e.g., Bracht, 1999). Such efforts will also be consistent with advocacy for conducting more research in such settings at the outset of an intervention instead of at the end of efficacy and effectiveness trials (e.g., Glasgow & Steiner, 2012). We can devote more resources to identify effective policies. Research is particularly vital on getting policies adopted. We can conduct more research on media interventions. Some of this would evaluate media interventions to affect individual behavior but we also need research to develop and evaluate strategies to influence adoption of policies that can improve wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1R01AA021726) and the National Institute of Child Health and Development (1R01HD060922) provided financial support for the author during his work on this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA, NICHD, or the National Institutes of Health. The author thanks Christine Cody for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research involving human participants and/or animals: This article has no methods section and provides no other information on studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Abramowitz M, Albrecht J. The Community Loss Index: A new social indicator. Social Service Review. 2013;87:677–724. [Google Scholar]

- Abroms LC, Maibach EW. The effectiveness of mass communication to change public behavior. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:219–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Pollard JA, Catalano RF, Baglioni AJ., Jr Measuring risk and protective factors for substance use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors. Evaluation Review. 2002;26:355–381. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0202600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Bradley RH. Those who have, receive: The Matthew effect in early childhood intervention in the home environment. Review of Educational Research. 2005;75:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Murray DM, Shadish WR. Empirically supported treatments or type I errors? Problems with the analysis of data from group-administered treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:924–935. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron J. Making policy work: the lesson from medicine (commentary) Education Week. 2007 Online at http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2007/05/23/38baron.h26.html?qs=Baron. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. Direct written testimony in the case of the U.S.A. vs. Phillip Morris et al. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. Corporate externalities: A challenge to the further success of prevention science. Prevention Science. 2011;12:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. The nurture effect: How the science of human behavior can improve our lives and our world. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger; 2015a. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. Evolving a more nurturing capitalism: A new Powell memo. This View of Life. 2015b Available at https://evolution-institute.org/article/evolving-a-more-nurturing-capitalism-a-new-powell-memo/ [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Cody C. Integrating the human sciences to evolve effective policies. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2013;90S:S152–S162. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Ary DV, Smolkowski K, Duncan TE, Black C. A randomized control trial of a community intervention to prevent adolescent tobacco use. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:24–32. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Ary D, Wagenaar AC. The value of interrupted time-series experiments for community intervention research. Prevention Science. 2000;1:31–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1010024016308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Brennan PA, Foster SL, Holder HD. Helping adolescents at risk: Prevention of multiple problem behaviors. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Embry DD. A framework for intentional cultural change. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2013;2:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Flay BR, Embry DD, Sandler I. Nurturing environments and the next generation of prevention research and practice. American Psychologist. 2012;67:257–271. doi: 10.1037/a0026796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Severson H, Ary DV, Faller C, Gallison C, Thompson R, Lichtenstein E. Do smoking prevention programs really work? Attrition and the internal and external validity of an evaluation of a refusal skills training program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1987;10:159–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00846424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Taylor TK. Why have we been more successful in reducing tobacco use than violent crime? American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:269–302. doi: 10.1023/A:1005155903801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracht N. Health promotion at the community level. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Calam R, Sanders MR, Miller C, Sadhnani V, Carmont S. Can technology and the media help reduce dysfunctional parenting and increase engagement with preventative parenting interventions? Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:347–361. doi: 10.1177/1077559508321272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardosos G. Societies in transition to the network society. In: Castells M, Cardoso G, editors. The network society: From knowledge to policy. Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins Center for Transatlantic Relations; 2005. pp. 23–70. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Current cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61:889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Patterson GR, Ge X. It takes two to replicate: A mediational model for the impact of parents' stress on adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Sullivan LM. Non-inferiority trials: design concepts and issues–the encounters of academic consultants in statistics. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22:169–186. doi: 10.1002/sim.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Snyder J. An introduction to the special issue on advances in process and dynamic system analysis of social interaction and the development of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:575–578. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047317.96104.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eamon MK. The effects of poverty on children's socioemotional development: An ecological systems analysis. Social Work. 2001;46:256–266. doi: 10.1093/sw/46.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Van Nguyen T, Caspi A. Linking family hardship to children’s lives. Child Development. 1995;56:361–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embry DD, Biglan A. Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11:75–113. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Jones D, Greenberg MT, Osgood DW, Bontempo D. Effects of the Communities That Care model in Pennsylvania on change in adolescent risk and problem behaviors. Prevention Science. 2010;11:163–171. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Chamberlain P. Multidimensional treatment foster care a program for intensive parenting, family support, and skill building. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2000;8:155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR. Efficacy and effectiveness trials (and other phases of research) in the development of health promotion programs. Preventive Medicine. 1986;15:451–474. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Burton D. Effective mass communication strategies for health campaigns. In: Atkin C, Wallack L, editors. Mass communication and public health: Complexities and conflicts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, Castro FG, Gottfredson D, Kellam S, Ji P. Standards of evidence: Criteria for efficacy, effectiveness, and dissemination. Prevention Science. 2005;6:151–175. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon Model of Parent Management Training. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Lynch JW, Smith GD. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality in adulthood: Systematic review and interpretation. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26:7–21. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Steiner JF. Comparative effectiveness research to accelerate translation: Recommendations for an emerging field of science. In: Brownson RC, Colditz G, Proctor E, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science and practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Cook TD, Gardner FEM, Gorman-Smith D, Howe GW, Sandler IN, Zafft KM. Standards of evidence for efficacy, effectiveness, and scale-up research in prevention science: next generation. Prevention Science. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0555-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Wething H. US poverty rates higher, safety net weaker than in peer countries. Economic Policy Institute Issue brief #339. 2012 Available online at http://www.epi.org/publication/ib339-us-poverty-higher-safety-net-weaker/ [Google Scholar]

- Greene CJ, Morland LA, Durkalski VL, Frueh BC. Noninferiority and equivalence designs: issues and implications for mental health research. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:433–439. doi: 10.1002/jts.20367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JS, Pierson P. Winner-take-all politics: Public policy, political organization, and the precipitous rise of top incomes in the U.S. Politics & Society. 2010;38:152–204. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JS, Pierson P, Moyers BD. Winner-take-all politics. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins J, Oesterle S, Brown EC, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Youth problem behaviors 8 years after implementing the communities that care prevention system: A community-randomized trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168:122–129. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Clingempeel WG, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Four-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy with substance-abusing and substance-dependent juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. The ghost map. New York: Riverhead Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman HB, Haggerty KP, Steketee M, Fagan A, Hanson K, Hawkins JD. Communities that care, core elements and context: Research of implementation in two countries. Social Development Issues. 2009;30:42–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorda V, Sarabia JM. Well-being distribution in the globalization era: 30 years of convergence. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2014 March 2014, N. P. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Koretz D, Mościcki EK. Core elements of developmental epidemiologically based prevention research. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:463–482. doi: 10.1023/A:1022129127298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, Biglan A, Flay BR Promise Neighborhoods Research Consortium. Creating nurturing environments: A science-based framework for promoting child health and development within high-poverty neighborhoods. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:111–134. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0095-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, Tobler AL, Delisle AL, Ryan JO, Wagenaar AC. Beyond the clinic: improving child health through evidence-based community development. BMC Pediatrics. 2013;13:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-172. Available at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/13/172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro K, O'Mara RJ, Wagenaar A. Mechanisms of legal effect: perspectives from public health. Public Health Law Research Methods Monograph Series. 2012 Apr 10; Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2042591. [Google Scholar]

- Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:1167–1170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein E, Zhu SH, Tedeschi GJ. Smoking cessation quitlines: an under-recognized intervention success story. American Psychologist. 2010;65:252–261. doi: 10.1037/a0018598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwee S. GOP is an anti-science party of nuts (sorry, Atlantic) Salon; 2013. Nov, http://www.salon.com/2013/11/13/gop_is_an_anti_science_party_of_nuts_sorry_atlantic. [Google Scholar]

- McLean B, Nocera J. All the devils are here: unmasking the men who bankrupted the world. London: Penguin UK; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek P, Biglan A, Hawkins JD. Community-monitoring systems: Tracking and improving the well-being of America’s children and adolescents. Falls Church, VA: SPR; 2004. at http://www.preventionresearch.org/advocacy/community-monitoring-systems/ [Google Scholar]

- Murray DM. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. Bethesda, MD: USDHHS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols MP, Schwartz RC. Family therapy: Concepts and methods. New York: Allyn & Bacon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL. The nurse–family partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:5–25. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosino A, Soydan H. The impact of program developers as evaluators on criminal recidivism: Results from meta-analyses of experimental and quasi-experimental research. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2005;1:435–450. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A, Stuckler D, McKee M, Gunnell D, Chang SS, Basu S. Increase in state suicide rates in the USA during economic recession. The Lancet. 2012;380:1813–1814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;90:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR. Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2:71–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1021843613840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Arnds K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the Family Check-Up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Sharma M. Globalization, threatened identities, coping and well-being. Psychological Studies. 2010;55:313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities. JAMA. 2009;301:2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Greenberg M. Impact challenges in community science-with-practice: lessons from PROSPER on transformative practitioner-scientist partnerships and prevention infrastructure development. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48:106–119. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Guyll M, Redmond C, Greenberg M, Feinberg M. Six-year sustainability of evidence-based intervention implementation quality by community-university partnerships: The PROSPER study. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48:412–425. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9430-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: USDHHS; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States v. Philip Morris USA, Inc. Civil Action No. 99-2496 (DDC 2012), Final Order. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC, Biglan A, Boruch RF, Castro FG, Collins LM, Flay BR, Schinke SP. Replication in prevention science. Prevention Science. 2011;12:103–117. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Burris SC, editors. Public health law research: Theory and methods. New York: Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Maldonado-Molina M, Wagenaar BH. Effects of alcohol tax increases on disease mortality in Alaska: Time-series analyses from 1976 to 2004. 2009;99:1464–1470. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallack L, Dorfman L. Media advocacy: A strategy for advancing policy and promoting health. Health Education & Behavior. 1996;23:293–317. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren K. A fighting chance. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Mihalic SF. The Incredible Years: Parent, teacher and child training series. Boulder, CO: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The spirit level: why greater equality makes societies stronger. London: Bloomsbury Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS. The neighborhood project: Using evolution to improve my city, one block at a time. New York: Little, Brown; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS, Hayes SC, Biglan A, Embry DD. Evolving the future: Toward a science of intentional change. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2014;37:395–416. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X13001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, Beardslee WR. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. American Psychologist. 2012;67:272–284. doi: 10.1037/a0028015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]