Abstract

Intranasal administration provides a non-invasive drug delivery route that has been proposed to target macromolecules either to the brain via direct extracellular cranial nerve-associated pathways or to the periphery via absorption into the systemic circulation. Delivering drugs to nasal regions that have lower vascular density and/or permeability may allow more drug to access the extracellular cranial nerve-associated pathways and therefore favor delivery to the brain. However, relative vascular permeabilities of the different nasal mucosal sites have not yet been reported. Here, we determined that the relative capillary permeability to hydrophilic macromolecule tracers is significantly greater in nasal respiratory regions than in olfactory regions. Mean capillary density in the nasal mucosa was also approximately 5-fold higher in nasal respiratory regions than in olfactory regions. Applying capillary pore theory and normalization to our permeability data yielded mean pore diameter estimates ranging from 13–17 nm for the nasal respiratory vasculature compared to <10 nm for the vasculature in olfactory regions. The results suggest lymphatic drainage for CNS immune responses may be favored in olfactory regions due to relatively lower clearance to the bloodstream. Lower blood clearance may also provide a reason to target the olfactory area for drug delivery to the brain.

Intranasal delivery is a well-established route to non-invasively target therapeutics to the peripheral compartment via the systemic circulation1. It avoids the gastrointestinal metabolism and hepatic first-pass elimination often associated with the oral route, allowing its use with peptides and protein therapeutics that are typically degraded following oral delivery1. Another emerging attribute of the intranasal delivery route–its ability to potentially target small fractions of therapeutics to the brain by circumventing the blood-brain barrier and blood-CSF barriers–has begun to receive much more attention in the past decade2,3,4. Intranasal administration has been shown to have an advantage over other parenteral systemic administration routes for the delivery of biological macromolecules such as peptides5,6, proteins7,8,9, oligonucleotides10 and gene vectors11 to the brain. We have previously described how labeled proteins and other macromolecule tracers may cross the nasal epithelia via paracellular or transcellular transport to reach the underlying lamina propria of the nasal respiratory and olfactory regions, after which they may (i) be absorbed into nasal blood vessels to enter the systemic circulation, (ii) be absorbed into nasal lymphatic vessels and drain to the cervical lymph nodes, or (iii) directly access extracellular pathways (perivascular, perilymphatic or perineural) associated with the trigeminal and/or olfactory nerves to reach the brain2,3,8,9. Further widespread distribution within the brain was recently shown to involve convective transport within the perivascular spaces of cerebral blood vessels12. In theory, preferentially targeting a region of the nasal passage that has a lower blood vessel density (vascularity) and/or more restrictive capillary permeability characteristics (size-dependent transport across vessel walls) would help minimize delivery to the systemic circulation and thus enhance access to the cranial nerve-associated extracellular pathways leading to the brain3; indeed, previous work has shown that intranasal application of a vasoconstrictor can significantly increase peptide delivery to the olfactory bulbs through a reduction in the systemic absorption rate (likely mediated by maintenance of higher peptide levels in the olfactory mucosa due to decreased nasal mucosal blood flow)13. However, very limited information currently exists describing vascularity and relative capillary permeability for the different nasal mucosal sites, despite their obvious importance for drug delivery and disposition of intranasally applied small molecules and biologics (e.g. oligonucleotides, peptides, and proteins) as well as for better understanding of nasal physiological mechanisms (e.g. lymphatic clearance and immune responses).

The nasal mucosae consist of four types of surface epithelia (squamous, respiratory, transitional, and olfactory) along with their underlying loose connective tissue compartments (lamina propria) that contain blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, glands, and nerves14. Although species differences are apparent in the general architecture of the nasal passages (e.g. turbinate shape), the major difference between mammals is primarily in the relative percentage areas of the respiratory and olfactory mucosae that together occupy the vast majority of the nasal cavity (e.g. about a 50:50 olfactory:respiratory area ratio is observed in rats compared to an approximately 10:90 olfactory:respiratory area ratio in primates)2,14. A small number of previous studies have examined nasal mucosal vascular extravasation under different conditions, nearly all of which have focused on nasal leakage of Evans blue-labeled macromolecules from the plasma compartment of rats15,16,17. Evans blue extravasation studies have demonstrated that nasal mucosal blood vessels are fairly permeable when compared to the non-permeable blood vessels of the brain17 and have also provided some indication that there may be vascular permeability differences between respiratory and olfactory regions of the nasal mucosa16; however, a detailed, quantitative comparison of vascular properties across multiple nasal mucosal regions using a range of well-characterized vascular tracers has not yet been described. Such a comparison is necessary to reveal size-dependent permeability properties of the nasal vasculature that may critically inform and guide nasal drug delivery, e.g. to provide an explanation for which particular locations of the nasal passage might be targeted for greater brain delivery (with lower systemic absorption) and to better anticipate the disposition of larger biologics.

Most biologics are hydrophilic macromolecules surrounded by a strongly adsorbed layer of water, referred to as a hydration shell, that moves with the macromolecule18. Capillary ‘pore theory’19 suggests that passive exchange of hydrophilic molecules between the systemic circulation and tissue interstitium occurs along an osmotic or chemical gradient via microscopic pores that cover capillary walls. An established method to quantify the upper limit of vascular permeability of capillaries based on this pore theory19 is to systemically administer exogenous tracers of various sizes and compare accumulation of the tracers in the tissue interstitium that occurs as a result of transcapillary diffusion20,21. Transport of a hydrophilic molecule through a liquid-filled pore is expected to become increasingly ‘hindered’ or ‘restricted’ when the hydrodynamic diameter (dH) of the molecule approaches the pore diameter and analytical expressions for this behavior have been described for different pore geometries22. Here, we quantitatively investigated extravasation at ten different nasal mucosal sites utilizing a broad size range of different hydrophilic macromolecule tracers to assess whether significant regional differences in vascular permeability characteristics exist across and within the nasal respiratory and olfactory mucosae. We also estimated relative vascularity between the nasal respiratory and olfactory mucosae by counting putative capillaries in the lamina propria of each region. For vascular permeability measurements, we systemically administered Texas Red-labeled, fixable, hydrophilic macromolecules of increasing size to different animals, constraining the moles of fluorophore administered to facilitate comparisons between each of four tracers: Lysine-fixable Texas Red-conjugated 3 kDa dextran (TR-Dex3), lysine-fixable Texas Red-conjugated 10 kDa dextran (TR-Dex10), Texas Red-conjugated bovine serum albumin (66.5 kDa) (TR-BSA) and lysine-fixable Texas Red-conjugated 70 kDa dextran (TR-Dex70). To our knowledge, this study represents the first to examine regional differences in nasal capillary permeability to hydrophilic macromolecules of varying sizes. The findings reveal important differences in mucosal vascular properties between nasal respiratory and olfactory regions that provide guidance on the region of the nasal passage that might be targeted to maximize intranasal drug delivery to the brain and that we speculate may also have significance for physiological processes such as the efficiency of lymphatic drainage to regional lymph nodes.

Results

Determining the free diffusion coefficients and hydrodynamic diameters of lysine-fixable Texas Red-labeled 70 kDa Dextran and Texas Red-labeled bovine serum albumin using integrative optical imaging (IOI)

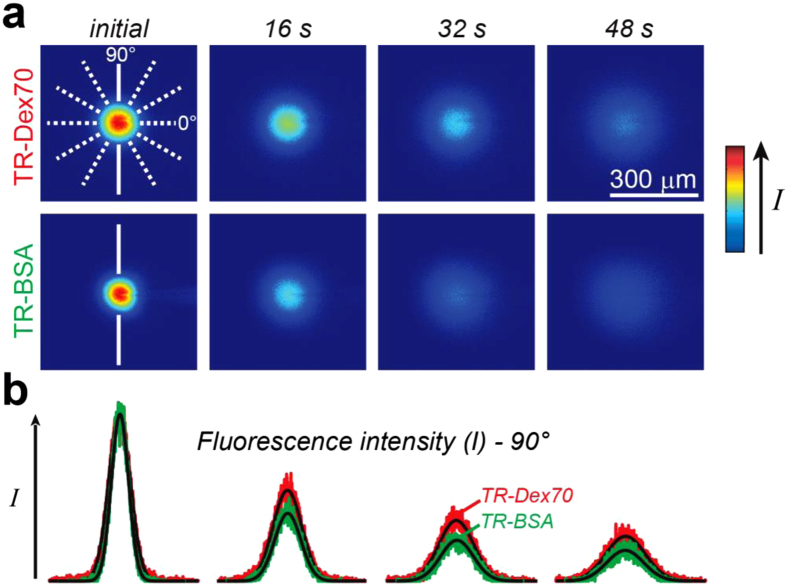

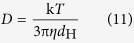

The use of dextrans to evaluate capillary permeability to hydrophilic macromolecules has been demonstrated previously for renal glomerular23 and intestinal capillaries24. Dextrans are inert polysaccharide molecules that are well tolerated upon systemic administration in rats and mice and induce minimal vascular leakage25. Texas red-labeled lysine-fixable dextrans are hydrophilic and anionic at physiological pH, which results in minimal interaction with lipid plasma membranes26 and renders them highly water soluble, allowing the use of high concentrations and thus higher signal-to-noise during ex vivo fluorescence imaging12. The incorporation of lysine residues in the dextran conjugates also makes it possible to fix them via cross-linking using an aldehyde fixative12, thus eliminating the possibility of post-mortem tracer movement in tissue12. We recently used integrative optical imaging (IOI), a highly validated and quantitative method for measuring diffusion in different media12,26,27,28,29, to determine the size of Texas red-labeled 3 and 10 kDa lysine-fixable dextrans12 by measuring their free diffusion coefficients (D) and then estimating their apparent hydrodynamic diameters (dH) with the Stokes-Einstein equation30 (Table 1). Here, we used IOI to obtain D and dH for TR-Dex70 and TR-BSA (Fig. 1, Table 1) to verify their properties and because these parameters have not yet been reported for lysine-fixable TR-Dex70, to the best of our knowledge. The D value we measured for TR-BSA (Table 1) agreed well with protein correlation predictions for monomeric BSA (8.6–9.2 × 10−7 cm2/s)30 as well as previous experimental measurements31. The experimental D and dH for TR-Dex70 (as well as the other two dextrans) were also well in line with prior estimates using nonlysine fixable dextrans28 as well as correlation predictions32. Taken together, the results confirmed the stability and monodisperse nature of all four tracers, yielding a 2.7–12.4 nm range of tracer dH to be used for nasal vascular permeability measurements (Table 1).

Table 1. Quantitative parameters for Texas Red-labeled tracers.

| TR-Dex3 | TR-Dex10 | TR-BSA | TR-Dex70 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate molecular weight (Da) | 3000 | 10,000 | 67,000 | 70,000 |

| Free diffusion coefficient (D, × 10−7 cm2/s) (n) | 24.6 ± 0.20 (12)a | 15.6 ± 0.15 (13)a | 9.00 ± 0.19 (15)b | 5.28 ± 0.12 (15)b |

| Hydrodynamic diameter (dH; nm)* | 2.67 ± 0.02 | 4.21 ± 0.04 | 7.30 ± 0.16 | 12.44 ± 0.29 |

| Moles of Texas Red fluorophore per mole of tracer | 0.4 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Intra-arterial tracer dose (μg)† | 375 | 500 | 1110.6 | 1166.7 |

| Intra-arterial Texas Red dose (moles) | 5.0 × 10−8 | 5.0 × 10−8 | 5.0 × 10−8 | 5.0 × 10−8 |

Values reported as mean ± SEM (n independent measurements).

*Apparent hydrodynamic diameter determined from the Stokes-Einstein equation [dH = (kT)/(3πηD), where k is the Boltzmann’s constant, T is absolute temperature, D is the free diffusion coefficient determined from IOI (37 ± 0.5 °C), and η is the viscosity of water (6.9152 × 10−4 Pa·s at T = 310 K)].

†dissolved in saline.

aLochhead et al.12.

bCurrent study. TR-Dex3, Texas Red-labeled lysine fixable 3 kDa dextran; TR-Dex10, Texas Red-labeled lysine fixable 10 kDa dextran; TR-BSA, Texas Red-bovine serum albumin; TR-Dex70, Texas Red-labeled lysine fixable 70 kDa dextran.

Figure 1. Characterization of tracer solution behavior by free diffusion measurements obtained using integrative optical imaging.

(a) Representative images after pressure ejection of Lysine fixable texas red labeled 70 kDa dextran (TR-Dex70) or BSA (TR-BSA) into dilute agarose. (b) Fluorescence intensity profiles were extracted from each image (TR-Dex70 data in red; TR-BSA data in green) and fit to the diffusion equation (black lines) along one of six different axes (shown in A, solid white lines; 90° axis for TR-BSA; 90° axis for TR-Dex70). Curve fitting yielded D for TR-Dex70 (37 °C) = 5.0 × 10−7 cm2/second and D for TR-BSA (37 °C) = 8.24 × 10−7 cm2/second for the records shown.

Extravasation of systemically administered hydrophilic tracer macromolecules in the nasal mucosa corresponds inversely with tracer size and is significantly greater in nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) and respiratory regions than in olfactory regions

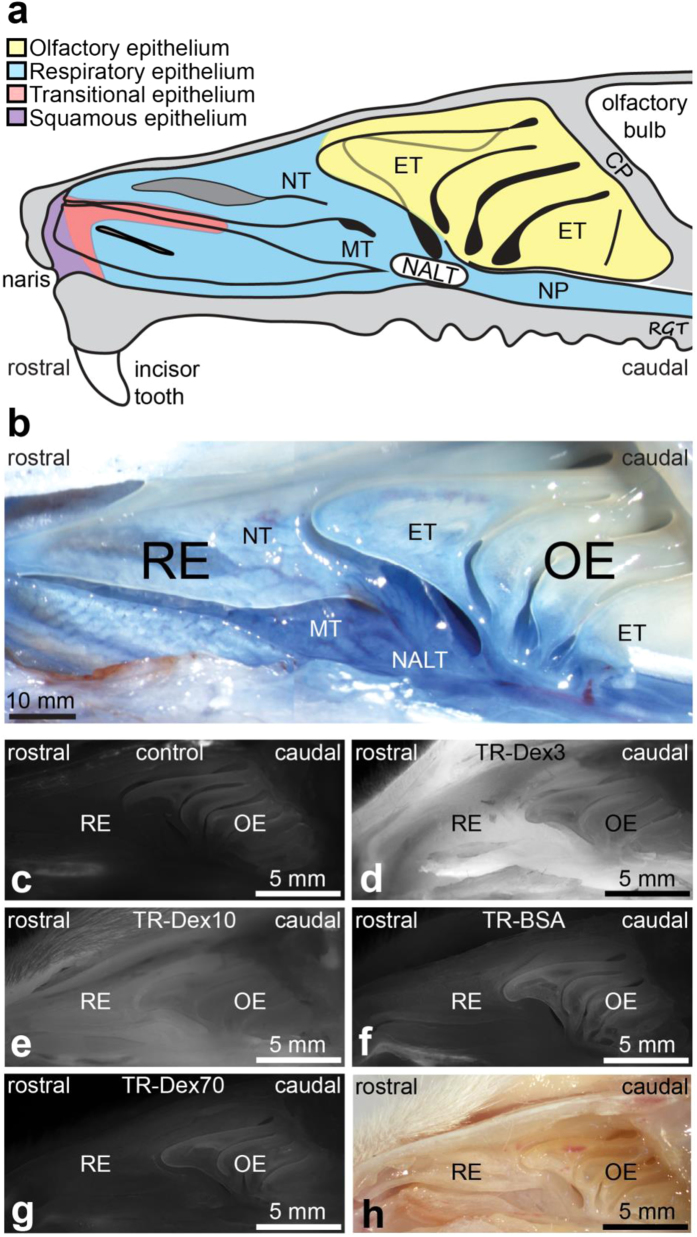

Previous studies examining extravasation of Evans blue-labeled macromolecules have primarily focused on the nasal mucosa of the lateral wall16,17. We also focused our study on the lateral wall of the nasal cavity because it can be isolated intact for imaging after careful removal of the nasal septum that separates the left and right nasal chambers. Another advantage of focusing on the lateral wall is that the predominant nasal respiratory and olfactory epithelial regions lining the rat nasal cavity are distinguishable based on turbinate structure3,14,33 (Fig. 2a), making it an ideal location to compare observed differences in vascular permeability across these regions. The lateral wall also includes a specialized region of interest containing aggregates of nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) within the lamina propria of the mucosa, located around the opening to the nasopharynx14,34 (Fig. 2a). Brightfield imaging following intra-arterial administration and 30 min circulation of the 961 Da Evans blue dye (similar to a previous study17) was useful in emphasizing the boundaries between the nasal respiratory areas containing the nasoturbinate (NT), maxilloturbinate (MT), and NALT from the more caudally placed ethmoturbinates that contain the olfactory mucosa (Fig. 2b; although six different ethmoturbinates exist, only the first, third, fifth, and sixth are visible on the outer portion of the lateral wall33). Extravasated Evans blue in the lateral nasal wall after endpoint saline and fixative perfusion suggested greater Evans blue content in respiratory areas (NT, MT, and NALT) than in the olfactory ethmoturbinate areas, as described previously16,17. Due to the high affinity of Evans blue for the 67 kDa albumin plasma protein after its administration into the plasma compartment, regional Evans blue extravasation is commonly interpreted as positive evidence of vascular permeability to a molecule at least the size of albumin (~7 nm; Table 1)15,16,17, despite possible confounding by non-negligible free Evans blue and/or Evans blue binding to smaller non-albumin proteins (reviewed elsewhere3,35).

Figure 2. Representative images of the lateral nasal cavity wall demonstrate size-dependent tracer extravasation.

(a) Schematic diagram showing the architecture and epithelial types lining the lateral wall of the rat nasal cavity. Abbreviations: CP, cribriform plate; ET, ethmoturbinate; NT, nasoturbinate; MT, maxilloturbinate; NP, nasopharynx; NALT, Nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (based on Mery et al.33 and Harkema et al.14). (b) Macroscopic aspect of the lateral wall of the rat nasal passage imaged following intra-arterial administration of 2% Evan’s blue (5 ml/kg) (based on a previous study17). Extravasation is noticeably greater within RE regions (NT and MT) and NALT than that observed in OE regions. (c) Representative image of background autofluorescence in the rat nasal cavity following intra-arterial administration of 0.9% saline (control). (d–g) Representative images of fluorescent tracer distribution in the rat nasal cavity following intra-arterial administration of (d) Texas Red-labeled lysine fixable 3 kDa dextran (TR-Dex3), (e) Texas Red-labeled lysine fixable 10 kDa dextran (TR-Dex10), (f) Texas Red-labeled bovine serum albumin (TR-BSA), and (g) Texas Red-labeled lysine fixable 70 kDa dextran (TR-Dex70). A bright field image of the rat nasal cavity is shown in (h) for comparison. Abbreviations: RE - respiratory epithelium; OE - olfactory epithelium.

To avoid issues with Evans blue signal interpretation and facilitate comparison of relative vascular permeability across the different nasal regions with a range of highly characterized tracers of different size, we adopted a different approach based on fluorescence imaging. In situ extravasation signal was imaged across different animals in the lateral nasal wall following intra-arterial administration of each of the four different Texas red-labeled BSA and dextran tracers characterized above (Table 1). We constrained the administered moles of Texas Red, all experimental and post-processing steps (30 min circulation time followed by saline and fixative perfusion), and in situ imaging parameters across all four tracers to facilitate comparisons of size-dependent extravasation (Table 1). Control experiments utilizing intra-arterial administration of saline with experimental, post-processing, and imaging parameters identical to that in tracer-administered animals were used to determine background autofluorescence in the different nasal regions (Fig. 2c). As expected, qualitative observation confirmed that the fluorescence intensity of each extravasated tracer in the nasal mucosa corresponded inversely with tracer size, i.e. TR-Dex3 (dH = 2.67 nm) signal (Fig. 2d) >TR-Dex10 (dH = 4.21 nm) signal (Fig. 2e) >TR-BSA (dH = 7.30 nm) signal (Fig. 2f) >TR-Dex70 (dH = 12.44 nm) signal (Fig. 2g). Additionally, close inspection clearly revealed greater fluorescence signal in the respiratory NT / MT regions and NALT compared to olfactory ET regions, particularly for the two smallest tracers (TR-Dex3 and TR-Dex10).

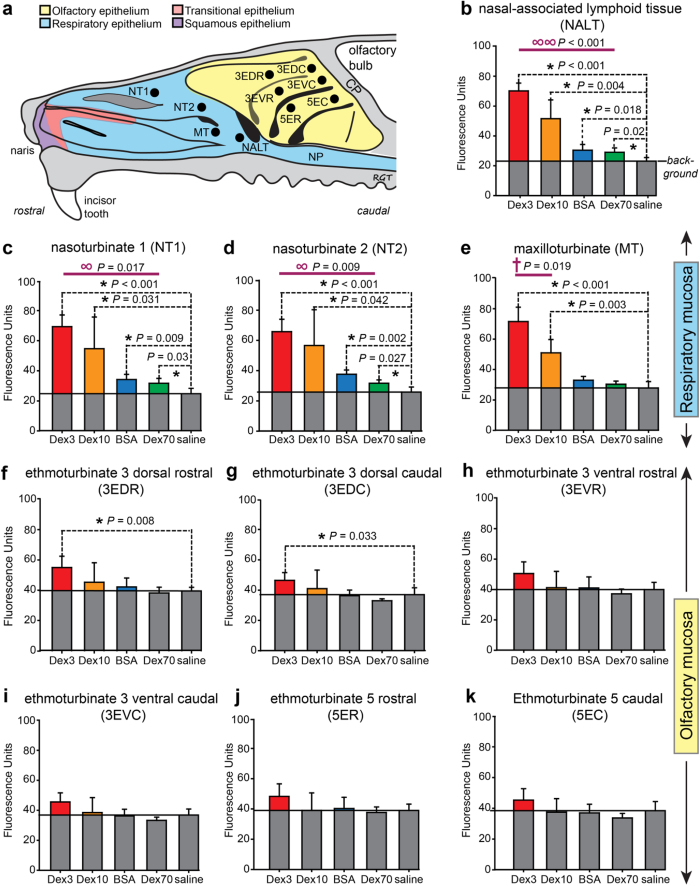

We next quantitatively analyzed the extravascular distribution of each tracer at ten distinct sites within the nasal mucosa (Fig. 3a): two different nasoturbinate sites (NT1 and NT2) and one maxilloturbinate site (MT) comprising the respiratory region; one NALT site; and six different ethmoturbinate sites (ET) from the two most accessible ethmoturbinates comprising the olfactory region. ImageJ was used to measure fluorescence intensity for each tracer in 24 pixel × 24 pixel sampling ellipses drawn around each region of interest across images obtained under identical conditions (exposure and magnification). Fluorescence intensity plots for each of the ten sites are shown with background autofluorescence levels indicated in Fig. 3b–k. Measured fluorescence intensity values were significantly above background for all four tracers only within the NALT (Fig. 3b), NT1 (Fig. 3c), and NT2 sites (Fig. 3d) of the respiratory region. The maxilloturbinate of the respiratory region yielded significant fluorescence intensity values above background only for the two smallest tracers (TR-Dex3 and TR-Dex10; Fig. 3e). Importantly, only two of the six sampled ethmoturbinate sites, representing the dorsal olfactory region of the third ethmoturbinate, exhibited fluorescence intensity values significantly above background for any tracer and this was limited to only the smallest tracer TR-Dex3 (Fig. 3f,g). Comparing across all the different sites, the value of background-subtracted TR-Dex3 fluorescence intensity was highest in the NALT, followed by the respiratory regions (NT1, NT2 and MT), with lowest levels observed in the olfactory regions (one way ANOVA; P < 0.001). Taken together, the results clearly show that the sampled nasal respiratory regions demonstrate significantly greater vascular permeability than the sampled olfactory regions.

Figure 3. Fluorescence intensity units quantified for all tracers across various regions of the nasal mucosa.

(a) Schematic showing regions sampled within the nasal mucosa. Abbreviations: 3ED, dorsal scroll of third ethmoturbinate (3EDR, rostral; 3EDC, caudal); 3EV, ventral scroll of third ethmoturbinate (3EVR, rostral; 3EVC, caudal); 5E, fifth ethmoturbinate (5ER, rostral; 5EC, caudal); NT1, nasoturbinate site 1; NT2, nasoturbinate site 2; MT, maxilloturbinate; NALT, nasal-associated lymphoid tissue.  Indicate areas sampled for image analysis using ImageJ (see text and methods for further details). Fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) within each sampled region above background for the NALT, respiratory areas (c–e), and olfactory areas (f–k) are denoted in color (i.e. grey fill denotes the level of background fluorescence for each region, determined from saline controls). Regions comprised by the respiratory mucosa and regions comprised by the olfactory mucosa are segregated to facilitate data comparisons. Values are given as means ± s.e.m. (n = 4) for each tracer or saline control treatment. Comparisons of data sets that followed a normal distribution used parametric statistical tests while comparisons of data sets that did not follow a normal distribution used non-parametric statistical tests. Abbreviations: ∞ One-way ANOVA (parametric) comparing fluorescence intensity above background between all tracers (α = 0.05); ∞ ∞ Kruskal-Wallis One-way analysis of variance on ranks (non-parametric) comparing fluorescence intensity above background between all tracers. † Two-tailed Student’s t-test (parametric) comparing fluorescence intensity above background between two tracers (α = 0.05). * Two-tailed Student’s t-test (parametric) comparing fluorescence intensity between each tracer and saline control (α = 0.05).

Indicate areas sampled for image analysis using ImageJ (see text and methods for further details). Fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) within each sampled region above background for the NALT, respiratory areas (c–e), and olfactory areas (f–k) are denoted in color (i.e. grey fill denotes the level of background fluorescence for each region, determined from saline controls). Regions comprised by the respiratory mucosa and regions comprised by the olfactory mucosa are segregated to facilitate data comparisons. Values are given as means ± s.e.m. (n = 4) for each tracer or saline control treatment. Comparisons of data sets that followed a normal distribution used parametric statistical tests while comparisons of data sets that did not follow a normal distribution used non-parametric statistical tests. Abbreviations: ∞ One-way ANOVA (parametric) comparing fluorescence intensity above background between all tracers (α = 0.05); ∞ ∞ Kruskal-Wallis One-way analysis of variance on ranks (non-parametric) comparing fluorescence intensity above background between all tracers. † Two-tailed Student’s t-test (parametric) comparing fluorescence intensity above background between two tracers (α = 0.05). * Two-tailed Student’s t-test (parametric) comparing fluorescence intensity between each tracer and saline control (α = 0.05).

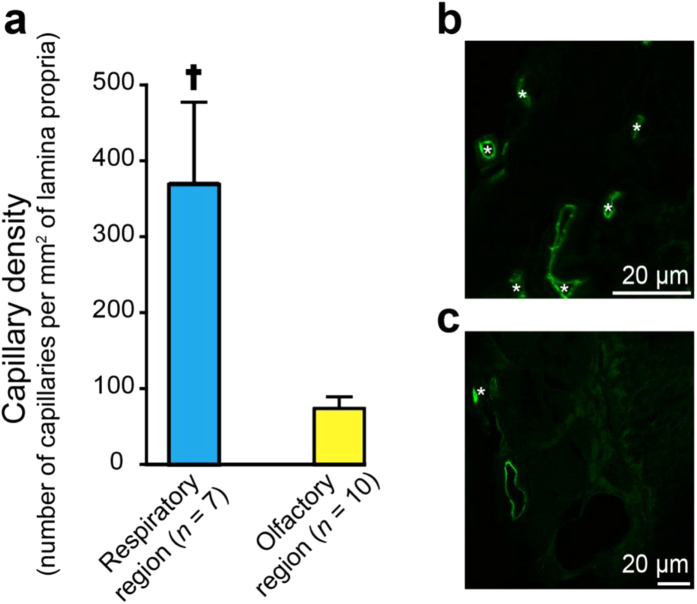

Nasal respiratory regions exhibit higher capillary density than olfactory regions

The primary site of tracer exchange between the systemic circulation and tissue extracellular space occurs at the level of the capillary; however, as with vascular permeability measurements, only limited information exists regarding vascularity differences between the nasal respiratory and olfactory mucosae. Yuasa has studied differences in the density of arteries and veins (excluding capillaries) between nasal regions of the Wistar rat, reporting an average vessel density of 111 large caliber (non-capillary) vessels per mm2 across the nasal mucosae and a relatively greater number of arteries and veins (counted together) in the olfactory mucosa compared to other areas36. To our knowledge, capillary density estimates between nasal mucosal regions have yet to be reported for the rat or human. We measured the mean density of capillaries (arbitrarily assigned as vessels with a lumen diameter less than 8 μm) in the respiratory (NT / MT) and olfactory (3rd–5thET) regions of the rat nasal mucosa by counting rat endothelial cell antigen-1 (RECA-1) positive capillary profiles in randomly selected areas of the lamina propria (Fig. 4). The mean capillary density within the lamina propria of the respiratory region (ρcapillary (resp.) = 367 ± 107 capillary profiles per mm2; mean ± SEM, n = 7) was found to be approximately 5-fold higher than that in the olfactory region (ρcapillary (olf.) =75 ± 15 capillary profiles per mm2; n = 10) (2 tailed Student’s t-test, P < 0.05).

Figure 4. Comparison of capillary density in different regions of the nasal passage.

(a) Measured capillary density in the respiratory region was significantly greater than the capillary density in the olfactory region. Values are given as means ± s.e.m. †Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test (non-parametric) comparing capillary density per mm2 of nasal lamina propria in the NALT or respiratory versus the olfactory region, P = 0.01. Only blood vessels with diameters less than 8 μm were counted for the analysis. Representative sections from (b) respiratory and (c) olfactory sites in the nasal mucosa were immunostained with anti- rat endothelial cell antigen (RECA-1) antibody (green). *Indicates RECA-1 positive vessels smaller than 8 μm (putative capillaries).

Estimating vascular pore diameters in different regions of the nasal lamina propria using hydrodynamic theory for hindered diffusion and a normalization method

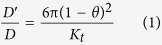

According to hydrodynamic theory for the hindered diffusion of large molecules in fluid-filled pores, tracer diffusion through pores will become increasingly hindered as the tracer hydrodynamic diameter (dtracer; here, dtracer = dH; Table 1) approaches the pore diameter (dpore), due to hindrance arising from the pore’s limited cross-sectional area and drag from the pore walls19,22. If a relatively inert tracer’s hydrodynamic diameter is vanishingly small compared to the diameter of a vascular pore it must extravasate through (i.e. dtracer/dpore approaches 0), the effective diffusion coefficient through the pore (D′) is expected to approach the tracer’s free diffusion coefficient in water (i.e. D′/D approaches 1), reflecting little if any hindrance from the pore on tracer diffusion. Conversely, if a tracer is very large such that dtracer approaches dpore (i.e. dtracer/dpore approaches 1), the tracer’s effective diffusion coefficient through the vascular pore becomes much less than the free diffusion coefficient until it eventually ceases to pass (i.e. D′/D approaches 0). Conveniently, analytical expressions exist for D′/D that depend only on the dtracer/dpore ratio and pore geometry22. The use and derivation of these expressions, based on hydrodynamic coefficients for axisymmetric diffusion of spheres on a centerline, have been extensively reviewed by Deen22. Assuming a cylindrical geometry typical of many vascular pores19,37, the following relationship applies38:

|

Where  and 0≤θ < 1 and Kt =

and 0≤θ < 1 and Kt =  −5.6117θ−0.3363θ2−1.216θ3 + 1.647θ4

−5.6117θ−0.3363θ2−1.216θ3 + 1.647θ4

As described previously, vascular permeability for hydrophilic macromolecules can be attributed primarily to pores on the walls of capillaries19. Cylindrical pores in the capillary wall may be physiologically interpreted as fenestrations in the endothelium that are filled with components of the glycocalyx39 and residual membrane proteins40, or alternatively as fluid-filled channels at the interendothelial clefts bounded by a matrix of junctional proteins41. Theoretically, the capillary pore diameter may be obtained by measuring the extravasation of an increasingly large, relatively inert set of hydrophilic tracers across capillary pores until diffusion ceases (i.e. D′/D → 0 as dtracer/dpore → 1). In practice, a range of well characterized tracers spanning a size range smaller than the expected capillary pore size is employed and the relative reduction in diffusion with increasing tracer size is interpreted according to the above-mentioned hydrodynamic theory for hindered diffusion and an assumed pore geometry (e.g. equation 1 for cylindrical vascular pores). In other words, deriving an expression for diffusive transport through constrained spaces (i.e. capillary pores) that depends on D′/D and then fitting the expression to experimental transport data for tracers of different size allows an estimate of pore size based on hydrodynamic theory.

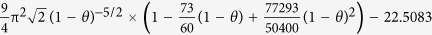

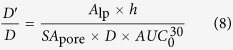

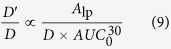

The net transport rate describing extravasation in a particular region of the nasal lamina propria following intra-arterial administration may be expressed as follows (adapted from42):

|

where Alp is the amount of tracer in the interstitial fluid of the nasal lamina propria, P is the tracer permeability coefficient across the capillary (cm/s), SA is the capillary surface area in a specific region of the nasal lamina propria (cm2), Cp is the tracer concentration in plasma, Clp is the tracer concentration in the nasal lamina propria, and α is the volume fraction of the nasal lamina propria interstitial fluid into which the systemically administered inert tracer distributes (α ≤ 1). At early times following intra-arterial administration of macromolecule tracers such as the dextrans and albumin employed in this study, plasma concentration will be much greater than the concentration in the nasal lamina propria (i.e. Cp ≫ Clp/α) allowing equation (2) to be simplified as follows:

|

Integrating equation (3) gives the following expression, assuming Alp = 0 at t = 0:

|

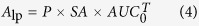

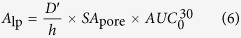

Here, the area under the plasma tracer concentration versus time curve (AUC) for each tracer was measured for 30 minutes after tracer administration (i.e. T = 30 min), yielding  (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S1). For our experiments, P can be expressed in terms of the tracer effective diffusion coefficient (D′) through the pore (assuming our macromolecule tracers may only access the lamina propria via transport through vascular pores) and the thickness of the capillary wall (h):

(Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S1). For our experiments, P can be expressed in terms of the tracer effective diffusion coefficient (D′) through the pore (assuming our macromolecule tracers may only access the lamina propria via transport through vascular pores) and the thickness of the capillary wall (h):

Figure 5. Concentration of tracer in plasma versus time.

Tracer plasma concentration over time after intra-arterial (IA) administration via the abdominal aorta. Animals were administered an IA dose of Texas Red labeled fluorescent tracer at a rate of 6.25 μl/sec followed immediately by a 0.9% saline chaser bolus injection of 500 μl. Tracer dose was selected in such a way as to constrain the total moles of Texas-Red administered (Table 1). Plasma samples were acquired at 10, 20, and 30 minutes after administration of the tracer. The concentration of tracer at time zero after IA administration was estimated using a simple one compartment model (ln (Cp) = ln (Cp0)−(kel*t)) for all tracers.

|

Substituting equation (5) into equation (4), we obtain:

|

We can further rearrange equation (6) as follows:

|

Equation (7) may be rearranged to yield an expression in terms of D′/D:

|

Assuming SApore and h remain constant for a given region of the nasal mucosa, equation (8) may be rewritten as a proportionality:

|

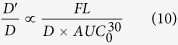

Finally, if we make the reasonable assumption that background-subtracted tracer fluorescence intensity (FL) for a given nasal mucosal site is a linear function of the amount of extravasated tracer in the nasal lamina propria (i.e. Alp α FL), equation (9) may be rewritten as:

|

Equation (10) may be used to provide estimates of the average vascular pore diameter (dpore) in different regions of the nasal mucosae. The D′/D ratio on the left-hand side of equation (10) can be evaluated by applying our experimental dtracer values (dH in Table 1) and varying the value of dpore over a range of probable values using equation (1). The right-hand side of equation (10) can be completely evaluated using our experimental data: FL, the arbitrary fluorescence intensity units (i.e. Texas red-associated signal) obtained for each tracer in a given region of the nasal lamina propria minus background auto-fluorescence intensity measured for the same region in saline control experiments (i.e. the colored bars in Fig. 3b–k); D, the free diffusion coefficient of each tracer (Table 1); and  , expressed in units of mol Texas red·min/L (Supplementary Table S1). Unfortunately, the constant of proportionality does not allow direct comparison between the left-hand side (D′/D ratio) and the right-hand side of equation (10) for a given tracer and nasal region. However, data from multiple tracers in a given region may be used to marginalize out the constant of proportionality by a normalization operation. In other words, normalization allows us to make use of expected behavior from hydrodynamic theory (i.e. D′/D; equation 1) and to simply vary dpore until we find the best fit to our experimental data (i.e. the right-hand side of equation 10).

, expressed in units of mol Texas red·min/L (Supplementary Table S1). Unfortunately, the constant of proportionality does not allow direct comparison between the left-hand side (D′/D ratio) and the right-hand side of equation (10) for a given tracer and nasal region. However, data from multiple tracers in a given region may be used to marginalize out the constant of proportionality by a normalization operation. In other words, normalization allows us to make use of expected behavior from hydrodynamic theory (i.e. D′/D; equation 1) and to simply vary dpore until we find the best fit to our experimental data (i.e. the right-hand side of equation 10).

Briefly, equation (10) is of the form X ∝ Y and we have data for each of four tracers such that Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4 are known while X1, X2, X3, and X4 can be evaluated explicitly by assuming a value for dpore (i.e. from hydrodynamic theory and equation 1). Our objective was to determine the value of dpore for a given nasal region that best fit our experimental data across multiple tracers. The method was to normalize each of the Y2, Y3, and Y4 values by Y1 to obtain the normalized Y terms Y2/Y1, Y3/Y1, and Y4/Y1. We then directly compared the normalized Y terms to similarly normalized X terms (X2/X1, X3/X1, and X4/X1) for a range of dpore values. The process was repeated using each of the smaller three tracers as the normalization reference for a given nasal region (e.g. normalizing by Y2 yielded terms Y1/Y2, Y3/Y2, and Y4/Y2), although in practice normalization with data from the smaller two tracers (TR-Dex3 and TR-Dex10) yielded more robust estimates (Supplementary Figure S1). A determination of the best fit average dpore for different nasal regions was then obtained by minimizing the mean-of-the-squared-differences (MSD) between the normalized Y terms and their corresponding normalized X terms (e.g. Y2/Y1 compared to X2/X1) by varying the value of dpore over a range of probable values up to 100 nm (Supplementary Figure S2a–c; see supplementary information for details). Applying this method to our experimental data from the respiratory regions where FL values were significantly above background for all four tracers (nasoturbinate and NALT regions), we obtained best fit average dpore estimates of approximately 15.0, 17.3, and 13.4 nm for the NT1, NT2, and NALT sites, respectively (Table 2). It was not possible to definitively estimate dpore for the respiratory MT site or the six olfactory sites because only two (MT), one (3EDR and 3EDC) or none of the tracer FL values were significantly above background (Fig. 3e–k). However, applying the method in a limited fashion to data for the two smallest tracers from the olfactory site that exhibited the greatest extravasation of Dex3 and Dex10 (3EDR) suggested a much smaller dpore value < 9 nm (Supplementary Figure S2d).

Table 2. Estimated capillary d pore (nm) in different regions of the nasal mucosa.

| Region | Normalization tracer | dpore estimate (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| NT1 | TR-Dex3 | 14.46 |

| TR-Dex10 | 13.30 | |

| TR-BSA | 17.13 | |

| mean ± s.e.m | 14.96 ± 1.14 | |

| NT2 | TR-Dex3 | 17.16 |

| TR-Dex10 | 15.79 | |

| TR-BSA | 18.93 | |

| mean ± s.e.m | 17.29 ± 0.91 | |

| NALT | TR-Dex3 | 12. 61 |

| TR-Dex10 | 12.44 | |

| TR-BSA | 15.13 | |

| mean ± s.e.m | 13.39 ± 0.87 |

Capillary pore size was estimated by normalization with each tracer for the NT1, NT2 and NALT sites of the nasal mucosa and expressed as mean ± SEM. Abbreviations: NT1, Nasoturbinate site 1; NT2, Nasoturbinate site 2; NALT, nasal-associated lymphoid tissue. See text and supplementary information for details.

Discussion

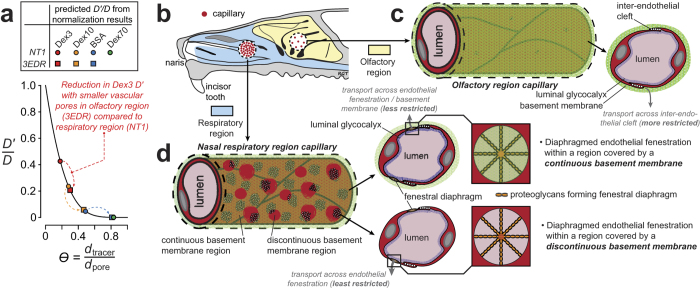

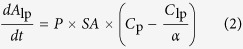

The major findings of this study are that (i) vascular permeability to hydrophilic macromolecule tracers is significantly greater in respiratory regions than in olfactory regions of the nasal passage, (ii) capillary vascularity (density) appears nearly five-fold higher in sampled nasal respiratory regions than in olfactory regions, and (iii) application of hydrodynamic theory suggests significantly larger vascular pore diameters (13–17 nm) at respiratory nasoturbinate and NALT sites compared to a rough estimate in the olfactory region (<9 nm). The reduced olfactory region extravasation we observed for all four tracers is therefore likely due to a combination of fewer capillaries (lower vascularity) and increased hindrance associated with smaller vascular pores; indeed, our estimate of pore diffusion coefficients (D′) from the application of hydrodynamic theory to our permeability data suggests an over 50% reduction in olfactory region D′ compared to the nasal respiratory region for the tracers used in this study (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. Relative vascularity and vascular permeability parameters may be used to infer physiological attributes of capillaries across different regions of the nasal mucosae.

Our study demonstrated greater extravasation of systemically applied hydrophilic macromolecular tracers at NALT and nasal respiratory sites compared to olfactory sites. Extravasation was size-dependent at all sites but the differences between sites can largely be attributed to two principal physiological characteristics: (i) differences in relative capillary vascular density, i.e. vascularity, and (ii) differences in vascular permeability determined by the characteristic average capillary wall pore size37. (a) Transport of a hydrophilic molecule through a fluid-filled pore will become increasingly ‘restricted’ when the hydrodynamic diameter (dH) of the molecule approaches the pore diameter; analytical expressions for this behavior have been described for different pore geometries22. The plotted black line (Equation (1)) describes the relationship between D′/D for an inert tracer and θ, the ratio of the tracer hydrodynamic diameter (dtracer) to the capillary pore diameter (dpore) for a hypothetical cylindrical fluid-filled pore. Plotted symbols indicate predicted dpore obtained from our application of hydrodynamic theory and normalization to data from the respiratory NT1 site and the olfactory 3EDR site, showing the effect of smaller pores in the olfactory site on transcapillary tracer diffusion (e.g. the TR-Dex3 effective diffusion coefficient, D′, is ~40% of the free diffusion coefficient, D, in NT1 versus only ~20% of D in 3EDR). (b–d) Schematic diagrams illustrating differences in vascularity (b) and hypothetical capillary pore structure in the olfactory (c) and nasal respiratory (d) regions, based on data from the present study and published findings. Our vascular permeability data and corresponding dpore estimates suggest hydrophilic tracer transport across the capillary wall in the olfactory region likely occurs through smaller, more restrictive inter-endothelial clefts (c), similar to those found in skeletal muscle capillaries41. Hydrophilic tracer transport across the capillary wall in respiratory regions appears more consistent with diffusion across diaphragmed endothelial fenestrations (d), as supported by previous ultrastructural studies37,49. Transcapillary exchange will be least restrictive in capillary regions exhibiting discontinuities in the loosely packed basement membrane49. See text for details.

Physiological interpretations of vascular permeability for hydrophilic macromolecules due to microscopic ‘pores’ on capillary walls have evolved over time. Transvascular movement of hydrophilic macromolecules is thought to occur through large pores on the capillary wall whose size is restricted by three components: the outer abluminal basement membrane43, the middle endothelial cell layer44 and the inner luminal glycocalyx45 (illustrated schematically for olfactory and respiratory regions in Fig. 6b–d, partly based on the results of the present study, as discussed below). Capillaries vary in their morphology with respect to the extent of these three barriers46, resulting in differing permeability to hydrophilic macromolecules circulating within the plasma37. Fenestrated capillaries of the intestinal wall, circumventricular organs, choroid plexus, endocrine glands, and skin at the extremities (e.g. fingers and soles)37 possess a continuous basement membrane with microdomains interrupting the plasmalemma in the form of fenestrations (generally exclusive from interendothelial clefts)40. A fenestration is a pore with a rim formed as a result of the plasmalemma of the luminal and abluminal sides of the endothelial cell being fused40,47. In diaphragmed fenestrated capillaries, fenestrations are occluded by a ~3 nm thick, uneven, non-lipid diaphragm39,47, composed of precipitated plasma protein39,40, glycocalyx39 and/or fibers of residual membrane proteins40; this structure is thought to restrict the passage of molecules larger than approximately 15 nm in diameter48. We estimated dpore to range from ~15–17 nm in the nasoturbinate region. Ultrastructural evidence suggests the occurrence of diaphragm-covered fenestrations in the capillaries of the respiratory region and a loosely packed, sometimes discontinuous basement membrane49, supporting our findings (Fig. 6d). High vascularity and vascular permeability in the respiratory region may be attributed to its role in humidifying and warming inhaled air, as well as a first line of immune defense against inhaled allergens50. We estimated dpore to be ~13 nm in the NALT region. High vascular permeability in NALT may be related to its immune role in facilitating antigen uptake, processing and presentation14,34. NALT, similar to the intestinal Peyer’s patches, acts as a mucosal inductive site for cell-mediated and humoral (antibody-mediated) antigen-specific immune responses. The NALT has a rich supply of lymphatic vessels that drain into the superficial and deep cervical lymph nodes, with high endothelial venules that act as sites for lymphocyte trafficking51.

Limited tracer extravasation within the olfactory region prevented a precise estimate of dpore. Nevertheless, our results suggest olfactory vascular pores may be much smaller (<9 nm in 3EDR) than at nasal respiratory sites, in agreement with ultrastructural observations that olfactory capillaries have few fenestrations, if any49, thereby limiting transport to the more restrictive interendothelial cleft as in skeletal muscle capillaries41. Skeletal muscle capillaries have a ~6–7 nm upper limit to permeability which is attributed to all three layers of the capillary wall41; however, since olfactory capillaries possess more loosely apposed endothelial cell junctions and a less compact basement membrane than that observed for skeletal muscle capillaries48, their clefts may be wider. Our data is consistent with that of Wolburg et al.17, who demonstrated with electron microscopy that transcardially perfused lanthanum nitrate, a small electron-dense tracer, extravasates through interendothelial clefts of olfactory blood vessels to label the subendothelial space. Although beyond the scope of the present study, it would be instructive to compare the relative expression of tight junction proteins (e.g. ZO-1, claudin-5, and occludin) between vessels of the olfactory and nasal respiratory regions; while Wolburg et al. have used immunocytochemistry to carefully describe ZO-1, claudin-5, and occludin positive staining of endothelial cells of the olfactory mucosa17, no such report yet exists for the nasal respiratory regions to the best of our knowledge. Further research will be needed to provide a better estimate of dpore in the olfactory region as well as to examine differences in junctional proteins between different vascular regions of the nasal mucosa.

Low relative vascularity and vascular permeability within the olfactory region likely favors lymphatic drainage from the olfactory lamina propria to regional lymph nodes. Previous work has shown that proteins injected into the brain parenchyma or CSF drain along olfactory nerves to the mucosa, where they are transported to the deep cervical lymph nodes for the induction of peripheral immune responses52. Recent evidence shows the CNS to possess a lymphatic drainage system in the form of dural lymphatic vessels53; these vessels may link with trigeminal nerve components that innervate the nasal respiratory mucosa54 and olfactory nerve components that traverse the skull at the cribriform plate54. Finally, lower vascularity and vascular permeability in the olfactory region suggests intranasal targeting of drugs to that area may favor brain delivery due, in part, to reduced clearance to the systemic circulation. The present study therefore provides new evidence in support of specialized nasal spray devices55 that preferentially target the olfactory region when attempting to deliver intranasally applied drugs to the brain.

Methods

Animals

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition; 2011). Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (180–200 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were housed individually or in groups of two at room temperature under a 12-h light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Animals were anesthetized with 1.5 g/kg urethane administered via intraperitoneal injections to effect. Body temperature of anesthetized animals was maintained at 37 °C using a homeothermic blanket (Harvard Apparatus). A 20 gauge cannula was then surgically inserted into the abdominal aorta.

Tracer administration

Evans blue (MP Biomedicals, LLC) permeability experiments were essentially done as previously described16,17, allowing 30 minutes circulation time after intra-arterial dye administration (2% Evans blue in saline, 5 ml/kg), followed by saline and fixative perfusion as described below for fluorescently labeled tracers. Four different fluorescently labeled fixable tracers (Thermo Fischer Scientific) of varying sizes were administered in separate experiments to estimate the capillary pore size in the rat nasal lamina propria: Lysine fixable Texas Red-conjugated 3 kDa dextran (TR-Dex3), lysine fixable Texas Red-conjugated 10 kDa dextran (TR-Dex10), Texas Red-conjugated Bovine serum albumin (TR-BSA) and lysine fixable Texas Red-conjugated 70 kDa dextran (TR-Dex70). In order to permit comparison between the different fluorescent tracers, the total injected dose of each tracer was adjusted such that the administered number of moles of Texas Red was constant for each tracer at 5 × 10−8 moles of Texas red. The required amount of each tracer (Table 1) was constituted in 500 μl of 0.9% sterile saline. For all experiments, the tracer was administered intra-arterially through the abdominal aortic cannula at a rate of 6.25 μl/sec followed immediately by a 0.9% saline chaser bolus injection of 500 μl. The tracer was then allowed to circulate for 30 minutes. Tracer molecules reaching the blood vessels in the nasal passages via the systemic circulation extravasated into the lamina propria to varying degrees depending on the region in the nasal cavity and the size of the tracer. In separate experiments, blood samples were collected at 10, 20 and 30 minutes after administration in order to estimate the area under the plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) for each tracer. At 30 minutes after tracer administration, the animals were perfused through the abdominal aortic cannula with 50 ml (~3 blood volumes) of 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (15 ml/min) to remove blood using a Gilson Minipuls 3 peristaltic pump. This was followed by perfusion with 500 ml fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS; 15 ml/min). Following perfusion, each animal was immediately decapitated and the nasal mucosa carefully exposed in order to measure extravasation of the fluorescently labeled tracers into the nasal lamina propria. In order to measure any auto-fluorescence in the nasal passage, control experiments were performed similarly with intra-arterial administration of 0.9% saline instead of tracer.

Tracer diffusion measurements and hydrodynamic size calculation

We measured the free diffusion coefficient (D) of TR-Dex70 and TR-BSA using integrative optical imaging (IOI), described in detail previously12,26,27,28,29. Briefly, a small pulse of the fluorescently labeled tracer is ejected into dilute (0.3%) agarose gel from a pulled micropipette (tip diameter = 3–6 μm) and the diffusion cloud is imaged over time using an epifluorescent microscope (Olympus BX61WI; 10x water immersion objective) connected to a CCD camera fitted with a Texas Red filter set (Fig. 1a). The short 0.1–0.2 ms, typically sub-nanoliter pulse ejection27 follows a point source approximation with an analytical solution to Fick’s second law that can be fit to the fluorescent intensity profiles extracted from the diffusion images (Fig. 1b). This fit is performed along six axes of the diffusion cloud and at each time point (ti) a parameter (γi) is calculated. A linear regression of γi2/4 versus ti returns a slope equal to D. For each measurement, the highest and lowest D values are discarded, yielding an average D value from the remaining four axes for each individual measurement. The free diffusion coefficient of each tracer is inversely related to the hydrodynamic diameter (dH) as described by the Stokes-Einstein equation30:

|

where k is Boltzmann’s constant, T is the absolute temperature (K), η is the viscosity of water (Pa*S), and dH is the hydrodynamic diameter of the macromolecule (nm) (Table 1).

Imaging

Fluorescence imaging of the nasal epithelium was carried out using an Olympus MVX10 fluorescent macro zoom microscope equipped with a Lumen Dynamics X-Cite 120Q illuminator, the appropriate filter set (Chroma, U-M49008XL) and a Hamamatsu C11440 Orca-flash 2.8 CMOS camera. Images of both treated and control animals were carefully acquired at the same magnification under the same light intensity and exposure time. Images were analyzed at specified regions (Figs 2 and 3a) with ImageJ using a 24 pixel x 24 pixel sampling ellipse (Rasband. http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2015). Brightfield imaging of the nasal epithelium was carried out using an Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope with an Olympus DP21 camera.

Estimating capillary density across different regions of the nasal mucosa

Animals were exsanguinated by perfusion with 50 ml 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4) followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours. The nasal passages were dissected out and cryoprotected overnight with 20% sucrose in PBS. The nasal passages were then flash frozen in isopentane chilled with dry ice, embedded in O.C.T. (Tissue-Tek) and cut into 15 μm sections on a cryostat (Leica CM1950). The sections were blocked with 10% goat serum in 0.01 M PBS (pH7.4) for 1 hour at room temperature. The sections were then immunostained by incubating in blocking buffer with mouse anti-Rat Endothelial Cell Antigen-1 (RECA-1) antibody (Abcam) (1:1000) overnight at 4 °C. Sections were washed in PBS and incubated for 1 hour in blocking buffer with DyLight 488 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Abcam) (1:500). After a final wash in PBS, sections were coverslipped in ProLong Diamond (Thermo Fischer Scientific). Laser scanning confocal microscopy was performed on the slices using an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope. ImageJ was used to measure the total area of the lamina propria and count the number of capillaries (RECA-1 positive vessels with a diameter less than 8 μm) in multiple sections of the respiratory and olfactory regions to calculate the capillary density in these regions of the nasal mucosa (Fig. 4).

Statistical analysis

Fluorescence intensity data (FL units) obtained using ImageJ was analyzed and graphed using SigmaPlot (version 11.2; Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Least squares analysis carried out to estimate capillary pore diameter was performed using MATLAB R2014a (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United States).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kumar, N. N. et al. Relative vascular permeability and vascularity across different regions of the rat nasal mucosa: implications for nasal physiology and drug delivery. Sci. Rep. 6, 31732; doi: 10.1038/srep31732 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michelle Pizzo, Geetika Nehra, Brynna Wilken-Resman and Alina Sievers (University of Wisconsin-Madison) for reviewing the manuscript. This work was generously supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the Clinical and Translational Science Award program administered through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NIH UL1TR000427 and KL2TR000428), the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation Accelerator Program, the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy, the Graduate School at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR 1UL1RR025011; VI and VS) and fellowships through the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America Foundation (DJW) and the NIH / University of Wisconsin Clinical Neuroengineering Training Program (National Research Service Award T32 EBO11434; DJW).

Footnotes

Robert Thorne acknowledges (i) periodically receiving honoraria for speaking to organizations within academia, foundations, and the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry and (ii) occasional service as a consultant to industry on CNS drug delivery. Jeffrey Lochhead and Robert Thorne acknowledge being inventors on patents and/or patent applications related to intranasal drug delivery.

Author Contributions N.N.K. contributed towards data collection, analysis, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. M.G., D.J.W. and J.J.L. contributed towards data collection. V.I. and V.S. contributed towards data analysis using MATLAB. R.G.T. contributed towards study conception and design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

References

- Patton J. S. & Byron P. R. Inhaling medicines: delivering drugs to the body through the lungs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6, 67–74 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead J. J. & Thorne R. G. Intranasal delivery of biologics to the central nervous system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64, 614–628 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead J. & Thorne R. In Drug delivery to the brain - Physiological concepts, Methodologies and Approaches. Advances in the Pharmaceutical Sciences (eds Hammarlund-Udenaes de Lange & Thorne) Ch. 14, 401–431 (Springer, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Henkin R. I. Intranasal delivery to the brain. Nat Biotechnol 29, 480 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born J. et al. Sniffing neuropeptides: a transnasal approach to the human brain. Nat Neurosci 5, 514–516 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosfeld M., Heinrichs M., Zak P. J., Fischbacher U. & Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature 435, 673–676 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scafidi J. et al. Intranasal epidermal growth factor treatment rescues neonatal brain injury. Nature 506, 230–234 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne R. G., Pronk G. J., Padmanabhan V. & Frey W. H. Delivery of insulin-like growth factor-I to the rat brain and spinal cord along olfactory and trigeminal pathways following intranasal administration. Neuroscience 127, 481–496 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne R. G., Hanson L. R., Ross T. M., Tung D. & Frey W. H. Delivery of interferon-beta to the monkey nervous system following intranasal administration. Neuroscience 152, 785–797 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner D. B., Frey W. H. & Hanson L. R. Intranasal delivery of siRNA to the olfactory bulbs of mice via the olfactory nerve pathway. Neurosci Lett 513, 193–197 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han I. K. et al. Enhanced brain targeting efficiency of intranasally administered plasmid DNA: an alternative route for brain gene therapy. J Mol Med (Berl) 85, 75–83 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead J. J., Wolak D. J., Pizzo M. E. & Thorne R. G. Rapid transport within cerebral perivascular spaces underlies widespread tracer distribution in the brain after intranasal administration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35, 371–381 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhuria S. V., Hanson L. R. & Frey W. H. Novel vasoconstrictor formulation to enhance intranasal targeting of neuropeptide therapeutics to the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 328, 312–320 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkema J. R., Carey S. A. & Wagner J. G. The nose revisited: a brief review of the comparative structure, function, and toxicologic pathology of the nasal epithelium. Toxicol Pathol 34, 252–269 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad L., Saria A., Lundberg J. M. & Anggård A. Increased vascular permeability in rat nasal mucosa induced by substance P and stimulation of capsaicin-sensitive trigeminal neurons. Acta Otolaryngol 96, 479–484 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson G., Bacci E., McDonald D. M. & Nadel J. A. Neurogenic plasma extravasation in the rat nasal mucosa is potentiated by peptidase inhibitors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 264, 509–514 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolburg H. et al. Epithelial and endothelial barriers in the olfactory region of the nasal cavity of the rat. Histochem Cell Biol 130, 127–140 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia de la Torre J. Hydration from hydrodynamics. General considerations and applications of bead modelling to globular proteins. Biophys Chem 93, 159–170 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappenheimer J. R., Renkin E. M. & Borrero L. M. Filtration, diffusion and molecular sieving through peripheral capillary membranes; a contribution to the pore theory of capillary permeability. Am J Physiol 167, 13–46 (1951). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotte G. Passage of dextran molecules across the blood-lymph barrier. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 211, 1–84 (1956). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman K. & Mayerson H. S. Dynamics of lymph and plasma protein exchange. Cardiologia 21, 296–307 (1952). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deen W. M. Hindered transport of large molecules in liquid-filled pores. AiChe Journal 33, 1409–1425 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield J. P. & Farquhar M. G. The permeability of glomerular capillaries to graded dextrans. Identification of the basement membrane as the primary filtration barrier. J Cell Biol 63, 883–903 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu N., Simionescu M. & Palade G. E. Permeability of intestinal capillaries. Pathway followed by dextrans and glycogens. J Cell Biol 53, 365–392 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu N. & Palade G. E. Dextrans and glycogens as particulate tracers for studying capillary permeability. J Cell Biol 50, 616–624 (1971). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C. & Tao L. Hindered diffusion of high molecular weight compounds in brain extracellular microenvironment measured with integrative optical imaging. Biophys J 65, 2277–2290 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolak D. J., Pizzo M. E. & Thorne R. G. Probing the extracellular diffusion of antibodies in brain using in vivo integrative optical imaging and ex vivo fluorescence imaging. J Control Release 197, 78–86 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne R. G. & Nicholson C. In vivo diffusion analysis with quantum dots and dextrans predicts the width of brain extracellular space. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 5567–5572 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne R. G., Lakkaraju A., Rodriguez-Boulan E. & Nicholson C. In vivo diffusion of lactoferrin in brain extracellular space is regulated by interactions with heparan sulfate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 8416–8421 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne R. G., Hrabetová S. & Nicholson C. Diffusion of epidermal growth factor in rat brain extracellular space measured by integrative optical imaging. J Neurophysiol 92, 3471–3481 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao L. & Nicholson C. Diffusion of albumins in rat cortical slices and relevance to volume transmission. Neuroscience 75, 839–847 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F., Nicholson C., Hrabe J. & Hrabetová S. Diffusion of flexible random-coil dextran polymers measured in anisotropic brain extracellular space by integrative optical imaging. Biophys J 95, 1382–1392 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mery S., Gross E. A., Joyner D. R., Godo M. & Morgan K. T. Nasal diagrams: a tool for recording the distribution of nasal lesions in rats and mice. Toxicol Pathol 22, 353–372 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyono H. & Fukuyama S. NALT- versus Peyer’s-patch-mediated mucosal immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 4, 699–710 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders N. R., Dziegielewska K. M., Møllgård K. & Habgood M. D. Markers for blood-brain barrier integrity: how appropriate is Evans blue in the twenty-first century and what are the alternatives? Front Neurosci 9, 385 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa T. Stereographic demonstration of the nasal cavity of the rat with reference to the density of blood vessels. Kaibogaku Zasshi 66, 191–200 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin H. Physiologic upper limits of pore size of different blood capillary types and another perspective on the dual pore theory of microvascular permeability. J Angiogenes Res 2, 14 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungay & Brenner. The motion of a closely-fitting sphere in a fluid filled tube. Int. J. Multiphase Flow. 1, 25–56 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Elfvin L. G. The ultrastructure of the capillary fenestrae in the adrenal medulla of the rat. J Ultrastruct Res 12, 687–704 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul G. G. Structure and formation of pores in fenestrated capillaries. J Ultrastruct Res 36, 768–782 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnovsky M. J. The ultrastructural basis of capillary permeability studied with peroxidase as a tracer. J Cell Biol 35, 213–236 (1967). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K., Pettigrew K. D. & Rapoport S. I. Lower limits of cerebrovascular permeability to nonelectrolytes in the conscious rat. Am J Physiol 235, H299–307 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charonis A. S. & Wissig S. L. Anionic sites in basement membranes. Differences in their electrostatic properties in continuous and fenestrated capillaries. Microvasc Res 25, 265–285 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minshall R. D. & Malik A. B. Transport across the endothelium: regulation of endothelial permeability. Handb Exp Pharmacol 176 Pt 1, 107–144 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry F. E. & Adamson R. H. Endothelial glycocalyx: permeability barrier and mechanosensor. Ann Biomed Eng 40, 828–839 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aird W. C. Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, a006429 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi F. & Palade G. E. Intestinal capillaries. I. Permeability to peroxidase and ferritin. J Cell Biol 41, 33–58 (1969). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K., Saito Y., Watanabe I. & Mizuhira V. Characteristics of capillary permeability in nasal mucosa. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 89, 377–382 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Diest P. & Kanan M. W. An ultrastructural study of the endonasal microcirculation in the Wistar rat during fetal and early postnatal life. J Anat 128, 293–300 (1979). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson C. G. et al. Plasma exudation as a first line respiratory mucosal defence. Clin Exp Allergy 21, 17–24 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper C. F. et al. The role of nasopharyngeal lymphoid tissue. Immunol Today 13, 219–224 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserr H. F., Harling-Berg C. J. & Knopf P. M. Drainage of brain extracellular fluid into blood and deep cervical lymph and its immunological significance. Brain Pathol 2, 269–276 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louveau A. et al. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523, 337–341 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspelund A. et al. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med 212, 991–999 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman J. D. & Ho R. J. Effects of localized hydrophilic mannitol and hydrophobic nelfinavir administration targeted to olfactory epithelium on brain distribution. AAPS PharmSciTech 12, 534–543 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.