Abstract

The 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is still the most used tool in cardiology clinical practice. Considering its easy accessibility, low cost and the information that it provides, it remains the starting point for diagnosis and prognosis. More specifically, its ability to detect prognostic markers for sudden cardiac death due to arrhythmias by identifying specific patterns that express electrical disturbances of the heart muscle, which may predispose to malignant arrhythmias, is universally recognized. Alterations in the ventricular repolarization process, identifiable on a 12-lead ECG, play a role in the genesis of ventricular arrhythmias in different cardiac diseases. The aim of this paper is to focus the attention on a new marker of arrhythmic risk, the early repolarization pattern in order to highlight the prognostic role of the 12-lead ECG.

Keywords: Ventricular repolarization, Cardiovascular diseases, Arrhythmic risk, Early repolarization, Arrhythmia

Core tip: By identifying specific patterns which are an expression of ventricular repolarization alterations, the 12-lead electrocardiogram plays an important role in the diagnosis of electrical disturbances and in the risk stratification of death due to arrhythmias. This review focuses the attention on the new early repolarization marker of arrhythmic risk and its prognostic implications.

INTRODUCTION

More than 100 years after its invention, the 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is still the most used tool in cardiology clinical practice. Moreover, it represents the starting point for diagnosis, given its easy accessibility and low cost.

Its ability to predict sudden cardiac death (SCD) due to arrhythmias by identifying specific patterns that express electrical disturbances of the heart muscle, which may predispose to malignant arrhythmias, is universally recognized.

On a surface 12-lead ECG it is possible to recognize a phase of ventricular depolarization, represented by the QRS complex, and a phase of ventricular repolarization (VR), that conventionally begins at the QRS wave and ends at the T waves. VR is made up of the J-wave, ST-segments and T-waves and U-waves[1,2]. Over the years several studies have analyzed the characteristics of VR and have recognized visible alterations as characteristic patterns on 12-lead ECG, emphasizing the role of the latter in the genesis of ventricular arrhythmias in different cardiac diseases[3-6].

From a pathophysiological point of view, it has been shown that changes in the process of VR can lead to malignant ventricular arrhythmias through abnormalities occurring in the action potential (AP) and in the refractory period of cardiac cells, thus leading to spatial heterogeneity and temporal fluctuations in repolarization, favoring the onset of arrhythmias[7,8].

However, an ECG can also be modulated by genetic factors which can determine an arrhythmogenic substrate that leads to an increased risk of SCD. This effect is particularly evident in inherited arrhythmogenic disorders such as long QT syndrome, short QT syndrome and Brugada syndrome, where the ECG can identify not only specific diagnostic alterations, but also prognostic indicators. This emphasizes the role of the ECG as an instrument not only for diagnostic but also for prognostic purposes[9].

The aim of this review is to focus the attention on a new marker of arrhythmic risk, i.e., the early repolarization (ER) pattern. The notions presented in the literature will be revised and the prognostic and predictive role of the 12-lead ECG will be highlighted, by recognizing, characterizing and carefully studying VR disturbances in the context of the ER pattern.

DEFINITION AND FAMILY FORM OF ER, A NEW ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHIC MARKER OF ARRHYTHMIC RISK

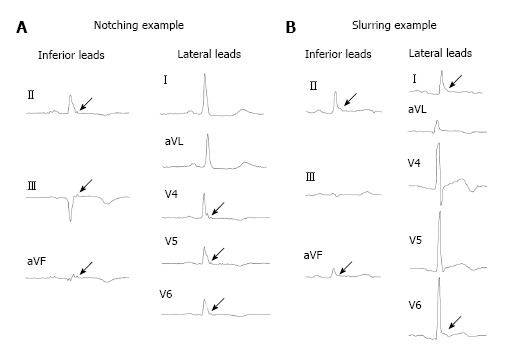

The early ER pattern as a 12-lead ECG marker of arrhythmic risk is a more recent discovery. It is characterized by a J-point elevation of at least 1 mm in two contiguous leads with a “notching” type appearance, i.e., a positive J-deflection inscribed in the S wave, or a “slurring”, i.e., a gradual transition of the QRS to the ST segment in the inferior, lateral or inferolateral leads, as defined by Haissaguerre in 2008[10] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Notching and slurring example of early repolarization. A: Notching example; B: Slurring example.

The J-point on the ECG waveform is historically defined as the junction between the end of the QRS complex and the beginning of the ST-segment[11].

In the 1953, Osborn[12] described the association between hypothermia and the appearance of positive deflections due to J-point elevation associated with VF. They were considered currents of injury. They became known as J-waves bearing his name (Osborn waves) and have become a generally accepted marker for clinical hypothermia.

In 1961, it was defined by Wasserburger et al[13] as an elevated take-off of the ST segment at the J-junction with downward concavity of the ST segment and symmetrical T waves. This elevation is manifested either as QRS slurring or notching in at least two inferior or lateral leads.

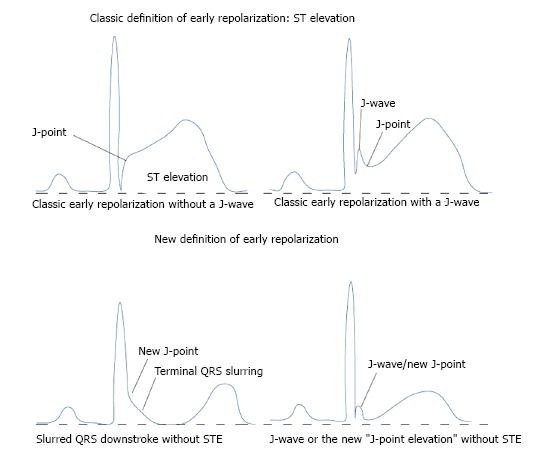

This definition remained in place until 2008 when Haissaguerre[10] shifted the focus from the ST-segment elevation to the J-point. J-point elevation was defined as being an elevation of at least 1 mm in two contiguous leads with a “notching” appearance, i.e., a positive J-deflection inscribed in the S wave, or “slurring”, i.e., a gradual transition of the QRS to the ST segment in the inferior, lateral or infero-lateral leads. The simultaneous presence of ST-segment elevation is not necessary for diagnosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Old and new definition of early repolarization. STE: ST elevation.

ER was historically considered a benign ECG variant, commonly seen in the anterolateral leads of young male athletes of black ethnicity but also in adolescents, accentuated by vagal tone and hypothermia[14-18]. In effect, an increase in vagal activity is known to cause an ST-segment elevation whereas sympathetic agonists normalize the ST segment[19].

A prevalence of between 1% and 5% has been estimated in healthy adults[13,20-22]. Furthermore, an intermittent pattern of ER is commonly observed, being only rarely present in all the ECGs performed successively on the same patient. It then becomes less common with age[23]. This evidence could be explained by the direct correlation of ER pattern with elevated testosterone plasma levels, as it is observed in young males. This would also explain the absence of the ER in older subjects[24].

Although not considered a marker of cardiovascular disease, ER has a practical importance because it may mimic the ECG of acute myocardial infarction, pericarditis, ventricular aneurysm, hyperkalemia or hypothermia. A dilemma may occur when a patient with ST variant presents with chest pain and no prior available ECG[25-28]. Unnecessary or incorrect diagnostic tests, therapeutic decisions, including administration of thrombolytic drugs[29], and hospital admissions might result from misinterpretation.

The available literature also provides evidence of a possible hereditary pattern of ER. In particular, a study of 500 families showed that subjects with at least one parent with ER were twice as likely to have the same ECG alteration. Family transmission is more frequent when the mother has the ER pattern, both for notching forms and for those in the lower location[30]. Such families have been shown to have a high incidence of sudden death, probably linked to ER.

There are also very rare forms of autosomal dominant inheritance[31]. In this context it was suggested that the Valsalva maneuver can unmask forms of ER which are not spontaneous on the surface ECG. The sensitivity of this maneuver, however, is considered to be low.

The question of whether family forms have a worse prognosis than sporadic forms remains.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL BACKGROUND OF J-WAVE AS AN ARRHYTHMIC MARKER

An ER pattern with the characteristics of the J-point elevation of at least 2 mm and a horizontal or descending pattern of the ST segment appears to increase the risk of developing ventricular arrhythmias, especially in structurally abnormal hearts. In fact, ER creates a kind of gradient of repolarization between adjacent areas that results in re-entry phenomena that cause the onset of arrhythmias.

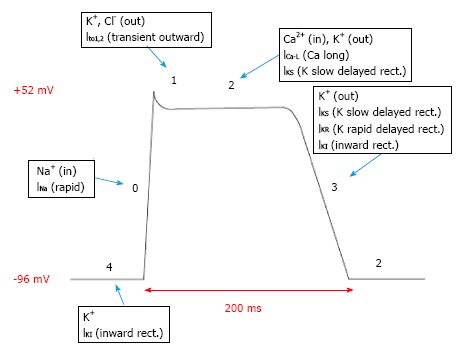

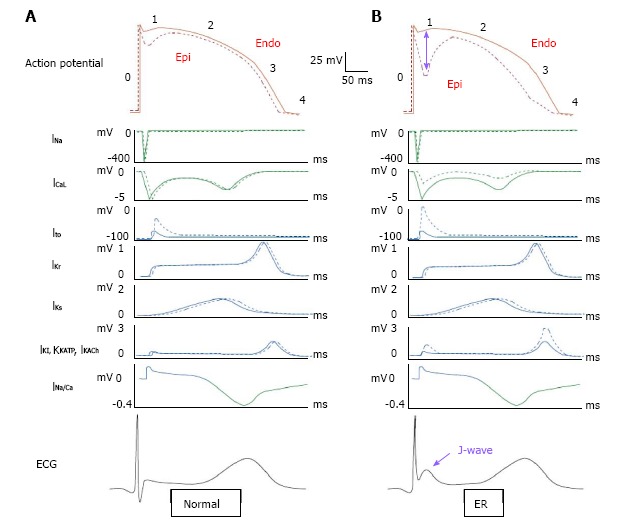

The J-wave comes from an alteration of the AP involving the epicardial, but not the endocardial, cells during phase 1 of the AP. In this period (ER phase) there are two ion currents of repolarization: Potassium tends to leak out (current Ito) and chlorine tends to enter into the cell (current ICl) while the front sodium current (INa-late) is gradually attenuated until it disappears. As a result of the loss of positive charges (K+) and the acquisition of negative charges (Cl-), the transmembrane potential is reduced to less positive values, from +30 to approximately 0 mV. The incoming sodium current (INa-late) has the opposite effect to that of Ito and ICl and, by bringing positive charges within the cell, it slows down the repolarization. However, since it is quickly depleted, its importance is relatively modest in physiological conditions (Figure 3). In subjects who have the ER patterns, repolarization proceeds more quickly than normal during phase 1, with a rapid reduction in the potential which passes from +30 to 0 mV or negative values[32]. The imbalance between outward and inward positive currents during phase 1 of the AP and thus the propagation of the AP dome from sites where it is maintained and to sites at which it is lost, might lead to a local re-excitation via phase-2 re entry which, in turn, may facilitate the development of premature beats. An increase in transmural dispersion might facilitate transmural propagation of the extrasystole predisposing to the development of polymorphic VT and VF[33] (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Action potential in physiological condition.

Figure 4.

The pathophysiological background of J wave. A: The normal action potential, underlying currents and corresponding ECGs. Epicardial (Epi) action potential and current are shown by dotted lines and endocardial (Endo) by solid lines. Depolarizing currents are depicted downward in green and repolarizing currents upward in blue. The Epi action potential has a characteristic notch caused by larger phase -1 Ito compared with Endo; B: Exaggeration of the Epi notch results from enhancement of net outward current. Phase-1 current flow from Endo to Epi produces the J-wave. The various ionic mechanisms that are believed to produce ER are shown with purple stars. INa: Inward sodium current; ICaL: Inward calcium currents; INa/Ca: Sodium calcium exchange; Ito: Transient outward current; IKs: Slow delayed rectifier current; IKr: Rapid delayed rectifier current; IK1: Inward rectifier current; IKATP: Adenosine triphosphate-sensitive current; IKACh: Acetylcholine-activated current; ECG: Electrocardiogram.

CLINICAL EVIDENCES OF ER/J WAVE AS A MARKER OF ARRHYTHMIC RISK

It is important to identify ECG characteristics that differentiate the "benign ER" pattern from the “malignant ER”[34,35] (Table 1). In fact, for the first time, an English case-control study has demonstrated the arrhythmogenic potential of ER by putting in relation the ER with the idiopathic ventricular fibrillation (IVF). In fact 206 subjects under the age of 60 with IVF, were compared with a control group of 412 healthy patients. The results suggested a correlation between ER and sudden cardiac arrest. It was observed that most of the subjects with the characteristic patterns were young males, with a history of unexplained syncope or cardiac arrest during sleep. In addition, at baseline ECG, ER was present mainly in the inferior-lateral leads[10].

Table 1.

The main studies evaluating the relationship between early repolarization pattern and death due to arrhythmia

| Ref. | No. of patients | Study population | ER pattern | Results |

| Tikkanen et al[36], 2009 | 10.864 | Community-based general population of middle-aged subjects | ER was stratified according to the degree of J-point elevation (> or = 0.1 mV or > 0.2 mV) in either inferior or lateral leads | ER pattern in the inferior leads is associated with an increased risk of death from cardiac causes in middle-aged subjects |

| Tikkanen et al[35], 2011 | 565 young healthy athletes-10 864 middle- aged subjects | 565 young healthy athletes compared with ECGs from a general population of 10864 middle-aged subjects | ER pattern with horizontal/descending or rapidly ascending/upsloping | ST-segment morphology variants associated with ER separates subjects with and without an increased risk of arrhythmic death in middle-aged subjects. Rapidly ascending ST segments after the J- point, the dominant ST pattern in healthy athletes, seems to be a benign variant of ER |

| Uberoi et al[43], 2011 | 29281 | Resting ambulatory ECGs | J-point elevation ≥ 0.1 mV- notching and slurring type in at least 2 lateral or inferior-lateral leads | No significant association between any components of early repolarization and cardiac mortality |

| Haïssaguerre et al[10], 2008 | 206 | Patients who were resuscitated after cardiac arrest due to IVF | Elevation of the QRS-ST junction of at least 0.1 mm inferior or lateral lead- QRS slurring or notching | Correlation between ER and sudden cardiac arrest |

| Nam et al[41], 2008 | 1410 | 1595 controls and 15 patients with IVF | J-point elevation ≥ 0.1 mV- notching and slurring type in at least 2 lateral or inferior leads | ER pattern is indicative of a highly arrhythmogenic substrate |

| Rosso et al[42], 2008 | 290 | 45 patients with idiopathic VF were compared with 124 age- and gender- matched control subjects and with 121 young athletes | J-point elevation ≥ 0.1 mV- notching and slurring type in at least 2 lateral or inferior-lateral leads | J-point elevation is found more frequently among patients with idiopathic VF than among healthy control subjects. The frequency of J-point elevation among young athletes is intermediate |

| Rosso et al[29], 2011 | 8980 | 331 patients with IVF and 8.649 controls | J waves > 2 mm | The presence of J waves > 2 mm in amplitude in asymptomatic adults is associated with a threefold increased of arrhythmic death |

| Aizawa et al[45], 2012 | 116 | Forty patients with J-wave-associated idiopathic VF compared with 76 non-VF patients | J-wave amplitude was measured in the beat immediately after a pause and compared with the mean J-wave measured in almost three beats before the pause. J waves were defined as those ≥ 0.1 mV above the isoelectric line | Pause-dependent augmentation of J waves was confirmed in about one-half of the patients with idiopathic VF after sudden R-R prolongation. Such dynamicity of J waves was specific to idiopathic VF and may be used for risk stratification |

| Cappato et al[37], 2010 | 386 | 21 athletes with a history of previous cardiac arrest of unknown etiology compared with more than 300 healthy athletes | ER pattern with horizontal/descending or rapidly ascending/upsloping | Athletes with a horizontal pattern of ER and ST were 11 times more at risk of cardiac arrest |

| Naruse et al[38], 2012 | 220 | patients with AMI | elevation of the QRS-ST junction of > 0.1 mV - 2 inferior or lateral leads- QRS slurring or notching | The presence of ER increased the risk of VF occurrences within 48 hours after the AMI onset |

| Rudic et al[40], 2012 | 60 | Patients with AMI | J-point elevation ≥ 0.1 mV- notching and slurring type- in at least 2 lateral or inferior leads | Early repolarization pattern seems to be associated with ventricular tachyarrhythmias in the setting of acute myocardial infarction |

| Tikkanen et al[39], 2012 | 964 | 432 consecutive victims of SCD because of acute coronary event and 532 survivors of such an event | elevation of the QRS-ST junction of > 0.1 mV - 2 inferior or lateral leads- QRS slurring or notching | The presence of ER increases the vulnerability to fatal arrhythmia during acute myocardial ischemia |

| Wu et al[44], 2013 | meta-analysis | Correlation of ER with a higher risk of arrhythmic death but not of cardiac death or death from other causes |

ER: Early repolarization; IVF: Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation; AMI: Acute myocardial infarction; SCD: Sudden cardiac death.

Tikkanen also considered the importance of defining a benign form of ER from a malignant one[35,36]. He studied a group of young athletes with ECG patterns of ER. Most of these presented an aspect of “rapidly ascending ST-segment blending with T-wave”. Naturally, this has been regarded as the benign form of ER. On the other hand, a minority of the athletes showed a pattern with an ST segment that remained flat, horizontal, or even descending towards the T-wave. The authors considered this to be the malignant variant of ER which is associated with arrhythmic mortality during long-term follow up. Moreover, subjects with an elevation of at least 2 mm of the J-point in the inferior leads had an increased risk of cardiac death. The study showed a relationship between mortality and ER and revealed that the risk of death was influenced by the seat, more common in the inferior leads, and the amount of elevation of the J-point, for values greater than 2 mm. In addition, Tikkanen et al[35,36] demonstrated that benign ER (ascending/upsloping ST segment) is associated with a significantly shorter QTc interval compared to the malignant form (horizontal/descending ST segment) which is associated with a significantly longer QRS duration (a prolonged QTc interval was defined as at least 440 ms for men and at least 460 ms for women). Therefore, benign ER appears to reflect earlier onset of repolarization, but malignant ER may reflect abnormal depolarization, possibly with underlying subtle structural disease[35,36].

The supposition of Tikkanen was later supported by a study that compared 21 athletes with a history of previous cardiac arrest of unknown etiology with more than 300 healthy athletes[37]. The study proved that athletes with a horizontal pattern of ER and ST were 11 times more at risk of cardiac arrest. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that patients with an ER pattern have a higher risk of having ischemic events and ischemic VF[38-40]. More specifically, the ER pattern with a horizontal ST segment was an independent predictor of sudden death[41]. As regards the malignant form of ER, the pattern of ER in the inferior lateral leads must be carefully considered. It is characterized by a deflection in the R-wave (slurred pattern) descending in the terminal part of the QRS in at least two inferior leads (II, III, aVF), in two lateral leads (I, aVL, V4-V6), or both. Numerous studies have demonstrated the association between a pattern of ER in these locations, especially in the inferior leads, and the presence of idiopathic VF (IVF)[26,29,42]. However, contrasting results in the available literature should be considered. In fact, in one study of nearly 30000 outpatients, with a mean follow up of 7 years, the negative prognostic effect of the ER patterns was not confirmed[43]. The only meta-analysis available of this emphasizes the correlation of ER with a higher risk of arrhythmic death but not of cardiac death or death from other causes[44].

In 1992 a Japanese study assessed the dynamicity of J-wave associated with idiopathic VF by analyzing its pause-dependent increase.

The J-wave amplitude was measured in the beat immediately after a pause and compared with the mean J-wave measured in almost three beats before the pause. The pause was considered as an abnormal sudden prolongation of the interval R-R, induced by arrhythmias such us sinus arrest, sinoatrial block, atrioventricular block, or atrial and ventricular premature beats.

It is interesting to note that the pause-dependent increase of J-wave was observed only in patients with idiopathic VF and in none of the control patients and this augmentation was associated with depression of the ST-segment or inversion of the T-waves. This dynamicity could be well explained by the pause-dependent augmentation in transient outward current (Ito) of the AP. In conclusion the authors suggested that the pausedependent augmentation was highly predictive of arrhythmic events and proposed a description of the characteristics of the “J-wave” potentially associated with IVF[45].

The same authors have further analyzed the J-wave dynamicity in the general patient population, with no symptoms and no history of IVF. They have observed an increase in amplitude of J-wave at high frequency but not at low frequencies and this may be due to a delay conduction[46].

So the analysis of the J-wave variations according to RR interval can be used to characterize the J-wave and use it for the arrhythmic risk stratification.

Focus on ECG features

Given the conflicting results between the different studies analyzed, possibly due to the non-uniformity of the case histories of patients treated, it is reasonable to think that, in addition to the seat and extent of the J-point changes, a key role is played by the characteristics of the segment elevation ST, as Tikkanen first demonstrated in his study, where the presence of a rapidly ascending ST was not associated with an increased risk of death from arrhythmia causes, unlike the detection of a horizontal or descending ST. The maximum risk was achieved by the combination of an ER pattern in the inferior leads with an ST-segment elevation at J-point greater than 2 mm and a horizontal-descending ST[35,36]. It is also interesting to note that patients with rapidly ascending ST were mostly young, had low blood pressure, and signs of left ventricular hypertrophy.

The literature shows that subjects with a good prognosis, who are young and athletic, with no evidence of structural heart disease have a high prevalence of an ER pattern with rapidly ascending ST elevation. Conversely, individuals with a poor prognosis, due to advanced age, and who have had a myocardial infarction with or without arrhythmic complications, have a high prevalence of an ER pattern with a horizontally-downward ST[47].

It is also important to evaluate the J-wave dynamicity in order to recognize ECG features predictive of arrhythmic risk, which are the pause dependent augmentation, the large amplitude and the concomitant horizontal-descending ST-segment[45].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, there is a correlation between 12-lead ECG VR patterns and cardiac death due to arrhythmias, especially in inferior or inferolateral localized forms, associated with a J-point elevation of at least 2 mm and a horizontal ST pattern. This pattern is more common in a poor prognosis population, i.e., in older subjects with a history of myocardial infarction or heart disease. Although ER is a common ECG finding, ER syndrome (ER with IVF) is rare[42].

Even in middle-aged individuals with an inferior ER of > 0.2 mV, the 3-fold increased SCD risk was not apparent until 10 years after the index ECG[35,36].

There have been no risk stratifies for asymptomatic ER subjects and, to date, no primary prevention strategy has been established. It is currently impossible to make recommendations based on this incidental ECG finding in an asymptomatic individual.

In fact, if it is simple and almost automatic to propose defibrillator implantation for a patient with a personal history of cardiac arrest and an ECG showing a typical framework, it is much less easy to take a decision if the same ECG is recorded by chance in an asymptomatic subject. The research carried out to date has highlighted some aspects of the problem but does not offer a one-size fits all approach. Moreover, it is not recommended that athletes should stop exercising or adopt specific preventive measures[48]. In addition, it should be noted that the usefulness of an electrophysiological study in these subjects is low considering that the inducibility of arrhythmias was observed in only 28% of cases[49]. In symptomatic subjects the etiology of symptoms should be evaluated. In cases of unexplained syncope with ER, an ECG may arouse suspicion if there is also a family history of sudden death or the occurrence of palpitations before syncope. Ventricular arrhythmias, if confirmed, clearly require the delivery of a defibrillation system in primary prevention[50]. It is still unclear if there is a different prognosis for patients presenting with notching or slurring patterns.

A greater characterization of the prognostic value of the ECG pattern of ER is necessary, but there is no doubt regarding the correlation between 12-lead ECG VR patterns and cardiac death due to arrhythmias and that the higher risk was achieved by the combination of an ER pattern in the inferior leads with an ST-segment elevation at J-point greater than 2 mm and a horizontal-descending ST. This pattern is also more common in a poor prognosis population, i.e., in older subjects with a history of myocardial infarction or heart disease.

Conversely, subjects with a good prognosis, who are young and athletic, with no evidence of structural heart disease show a high prevalence of an ER pattern with rapidly ascending ST elevation.

Moreover, the evidence of pause-dependent increase in J-wave amplitude, highlighted in patients with idiopathic VF, has proved to be highly specific and high predictive of arrhythmic events. This simple phenomenon may be used for the stratification of arrhythmic risk in patients with J-wave.

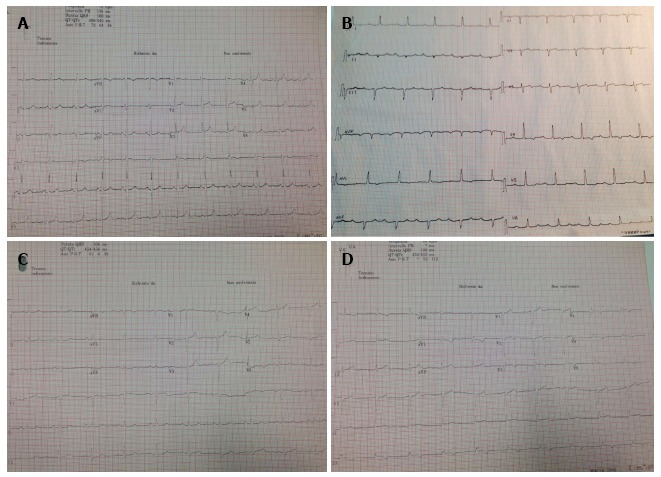

So, in conclusion, given the increased risk of major arrhythmic events in these subjects, it becomes important for the cardiologist to recognize the “malignant ER” pattern in order to improve the risk stratification of these patients (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Early repolarization in clinical practice. A: Example of ER pattern “notching tipe” in Inferior-lateral leads (D2, D3, aVF, V5, V6). Width: 1 mm; B: Example of ER pattern “slurring tipe” in lateral leads (D1, aVL, V5, V6). Width: 1 mm; C: Example of ER pattern “notching tipe” in Inferior leads (D2, D3, aVF). Width: 1.5 mm; D: Example of ER pattern “notching tipe” in lateral leads (V5, V6). Width: 1.8 mm. ER: Early repolarization.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: April 30, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Article in press: July 13, 2016

P- Reviewer: Aizawa Y, Bonanno C, Jaroszynski A, Rauch B, Skobel E S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Yan GX, Lankipalli RS, Burke JF, Musco S, Kowey PR. Ventricular repolarization components on the electrocardiogram: cellular basis and clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monitillo F, Leone M, Rizzo C, Passantino A, Iacoviello M. Ventricular repolarization measures for arrhythmic risk stratification. World J Cardiol. 2016;8:57–73. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zareba W, Moss AJ, le Cessie S. Dispersion of ventricular repolarization and arrhythmic cardiac death in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:550–553. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikeda T, Sakata T, Takami M, Kondo N, Tezuka N, Nakae T, Noro M, Enjoji Y, Abe R, Sugi K, et al. Combined assessment of T-wave alternans and late potentials used to predict arrhythmic events after myocardial infarction. A prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:722–730. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00590-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haigney MC, Zareba W, Gentlesk PJ, Goldstein RE, Illovsky M, McNitt S, Andrews ML, Moss AJ. QT interval variability and spontaneous ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT) II patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1481–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacoviello M, Forleo C, Guida P, Romito R, Sorgente A, Sorrentino S, Catucci S, Mastropasqua F, Pitzalis M. Ventricular repolarization dynamicity provides independent prognostic information toward major arrhythmic events in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger RD, Kasper EK, Baughman KL, Marban E, Calkins H, Tomaselli GF. Beat-to-beat QT interval variability: novel evidence for repolarization lability in ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1997;96:1557–1565. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turrini P, Corrado D, Basso C, Nava A, Bauce B, Thiene G. Dispersion of ventricular depolarization-repolarization: a noninvasive marker for risk stratification in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;103:3075–3080. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.25.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Napolitano C, Priori SG. [Role of standard resting ECG in the assessment of sudden cardiac death risk] G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2014;15:670–677. doi: 10.1714/1718.18768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haïssaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, Jesel L, Deisenhofer I, de Roy L, Pasquié JL, Nogami A, Babuty D, Yli-Mayry S, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2016–2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lepeschkin E, Surawicz B. The measurement of the duration of the QRS interval. Am Heart J. 1952;44:80–88. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(52)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborn JJ. Experimental hypothermia; respiratory and blood pH changes in relation to cardiac function. Am J Physiol. 1953;175:389–398. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1953.175.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasserburger RH, Alt WJ. The normal RS-T segment elevation variant. Am J Cardiol. 1961;8:184–192. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(61)90204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junttila MJ, Sager SJ, Freiser M, McGonagle S, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ. Inferolateral early repolarization in athletes. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2011;31:33–38. doi: 10.1007/s10840-010-9528-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP. Normal resting electrocardiographic variants in young athletes. Phys Sportsmed. 2008;36:69–75. doi: 10.3810/psm.2008.12.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wellens HJ. Early repolarization revisited. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2063–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0801060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazzoli JK, Soares PP, da Nóbrega AC, de Araújo CG. Electrocardiographic criteria for vagotonia-validation with pharmacological parasympathetic blockade in healthy subjects. Int J Cardiol. 2003;87:231–236. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00330-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krantz MJ, Lowery CM. Images in clinical medicine. Giant Osborn waves in hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:184. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm030851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasanuki H, Ohnishi S, Ohtuka M, Matsuda N, Nirei T, Isogai R, Shoda M, Toyoshima Y, Hosoda S. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation induced with vagal activity in patients without obvious heart disease. Circulation. 1997;95:2277–2285. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.9.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman MJ. Normal variants in the electrocardiogram leading to cardiac invalidism. Am Heart J. 1960;59:71–77. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(60)90386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottschalk CW, Craige E. A comparison of the precordial S-T and T waves in the electrocardiograms of 600 healthy young Negro and white adults. South Med J. 1956;49:453–457. doi: 10.1097/00007611-195605000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vacanti LJ. [Thoracic pain and early repolarization syndrome at the cardiologic emergency unit] Arq Bras Cardiol. 1996;67:335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh JA, Ilkhanoff L, Soliman EZ, Prineas R, Liu K, Ning H, Lloyd-Jones DM. Natural history of the early repolarization pattern in a biracial cohort: CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junttila MJ, Tikkanen JT, Porthan K, Oikarinen L, Jula A, Kenttä T, Salomaa V, Huikuri HV. Relationship between testosterone level and early repolarization on 12-lead electrocardiograms in men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1633–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eastaugh JA. The early repolarization syndrome. J Emerg Med. 1989;7:257–262. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(89)90357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brady WJ, Chan TC. Electrocardiographic manifestations: benign early repolarization. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:473–478. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(99)00010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brady WJ, Perron AD, Chan T. Electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation: correct identification of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and non-AMI syndromes by emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:349–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollander JE, Lozano M, Fairweather P, Goldstein E, Gennis P, Brogan GX, Cooling D, Thode HC, Gallagher EJ. “Abnormal” electrocardiograms in patients with cocaine-associated chest pain are due to “normal” variants. J Emerg Med. 1994;12:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(94)90699-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosso R, Adler A, Halkin A, Viskin S. Risk of sudden death among young individuals with J waves and early repolarization: putting the evidence into perspective. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reinhard W, Kaess BM, Debiec R, Nelson CP, Stark K, Tobin MD, Macfarlane PW, Tomaszewski M, Samani NJ, Hengstenberg C. Heritability of early repolarization: a population-based study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:134–138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gourraud JB, Le Scouarnec S, Sacher F, Chatel S, Derval N, Portero V, Chavernac P, Sandoval JE, Mabo P, Redon R, et al. Identification of large families in early repolarization syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oreto G, Luzza F, Donato A, Carbone V, Satullo G, Calabrò MP. L’elettrocardiogramma: un mosaico a 12 tessere. Torino: Centro Scientifico Editore; 2009. pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the Brugada syndrome and other mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis associated with ST-segment elevation. Circulation. 1999;100:1660–1666. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.15.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viskin S, Rosso R, Halkin A. Making sense of early repolarization. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:566–568. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Anttonen O, Aro AL, Luttinen S, Kerola T, Sager SJ, Rissanen HA, Myerburg RJ, Reunanen A, et al. Early repolarization: electrocardiographic phenotypes associated with favorable long-term outcome. Circulation. 2011;123:2666–2673. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tikkanen JT, Anttonen O, Junttila MJ, Aro AL, Kerola T, Rissanen HA, Reunanen A, Huikuri HV. Long-term outcome associated with early repolarization on electrocardiography. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2529–2537. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cappato R, Furlanello F, Giovinazzo V, Infusino T, Lupo P, Pittalis M, Foresti S, De Ambroggi G, Ali H, Bianco E, et al. J wave, QRS slurring, and ST elevation in athletes with cardiac arrest in the absence of heart disease: marker of risk or innocent bystander? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:305–311. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.945824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naruse Y, Tada H, Harimura Y, Hayashi M, Noguchi Y, Sato A, Yoshida K, Sekiguchi Y, Aonuma K. Early repolarization is an independent predictor of occurrences of ventricular fibrillation in the very early phase of acute myocardial infarction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:506–513. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.966952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tikkanen JT, Wichmann V, Junttila MJ, Rainio M, Hookana E, Lappi OP, Kortelainen ML, Anttonen O, Huikuri HV. Association of early repolarization and sudden cardiac death during an acute coronary event. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:714–718. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.970863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudic B, Veltmann C, Kuntz E, Behnes M, Elmas E, Konrad T, Kuschyk J, Weiss C, Borggrefe M, Schimpf R. Early repolarization pattern is associated with ventricular fibrillation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1295–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nam GB, Kim YH, Antzelevitch C. Augmentation of J waves and electrical storms in patients with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2078–2079. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0708182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosso R, Kogan E, Belhassen B, Rozovski U, Scheinman MM, Zeltser D, Halkin A, Steinvil A, Heller K, Glikson M, et al. J-point elevation in survivors of primary ventricular fibrillation and matched control subjects: incidence and clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uberoi A, Jain NA, Perez M, Weinkopff A, Ashley E, Hadley D, Turakhia MP, Froelicher V. Early repolarization in an ambulatory clinical population. Circulation. 2011;124:2208–2214. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu SH, Lin XX, Cheng YJ, Qiang CC, Zhang J. Early repolarization pattern and risk for arrhythmia death: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aizawa Y, Sato A, Watanabe H, Chinushi M, Furushima H, Horie M, Kaneko Y, Imaizumi T, Okubo K, Watanabe I, et al. Dynamicity of the J-wave in idiopathic ventricular fibrillation with a special reference to pause-dependent augmentation of the J-wave. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1948–1953. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aizawa Y, Sato M, Kitazawa H, Aizawa Y, Takatsuki S, Oda E, Okabe M, Fukuda K. Tachycardia-dependent augmentation of “notched J waves” in a general patient population without ventricular fibrillation or cardiac arrest: not a repolarization but a depolarization abnormality? Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adler A, Rosso R, Viskin D, Halkin A, Viskin S. What do we know about the “malignant form” of early repolarization? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:863–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corrado D, Pelliccia A, Heidbuchel H, Sharma S, Link M, Basso C, Biffi A, Buja G, Delise P, Gussac I, et al. Recommendations for interpretation of 12-lead electrocardiogram in the athlete. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:243–259. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haïssaguerre M, Sacher F, Nogami A, Komiya N, Bernard A, Probst V, Yli-Mayry S, Defaye P, Aizawa Y, Frank R, et al. Characteristics of recurrent ventricular fibrillation associated with inferolateral early repolarization role of drug therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, Blanc JJ, Brignole M, Dahm JB, Deharo JC, Gajek J, Gjesdal K, Krahn A, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009) Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631–2671. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]