Abstract

Objective:

To study the clinical profile and outcome of dengue fever in children at a tertiary care hospital in Puducherry.

Materials and Methods:

All children (0-12 years of age) diagnosed and confirmed as dengue fever from August 2012 to January 2015 were reviewed retrospectively from hospital case records as per the revised World Health Organization guidelines for dengue fever. The diagnosis was confirmed by NS1 antigen-based ELISA test or dengue serology for IgM and IgG antibodies, and the data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 statistical software. After collecting the data, all the variables were summarized by descriptive statistics.

Results:

Among the 261 confirmed cases of dengue fever non-severe and severe dengue infection was seen in 60.9% and 39.1%, respectively. The mean age (standard deviation) of the presentation was 6.9 + 3.3 years and male: female ratio was 1.2:1. The most common clinical manifestations were fever (94.6%), conjunctival congestion (89.6%), myalgia (81.9%), coryza (79.7%), headache (75.1%), palmar erythema (62.8%), and retro-orbital pain (51.3%). The common early warning signs at the time of admission were persistent vomiting (75.1%), liver enlargement (59.8%), cold and clammy extremities (45.2%), pain abdomen (31.0%), hypotension (29.5%), restlessness (26.4%), giddiness (23.0%), bleeding (19.9%), and oliguria (18.4%). The common manifestation of severe dengue infection was shock (39.1%), bleeding (19.9%), and multi-organ dysfunction (2.3%). The most common complications were liver dysfunction, acute respiratory distress syndrome, encephalopathy, pleural effusion, ascites, myocarditis, myositis, acute kidney injury, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Platelet count did not always correlate well with the severity of bleeding. There were six deaths (2.3%) and out of them four presented with impaired consciousness (66.6%). The common causes for poor outcome were multiorgan failure, encephalopathy, and fluid refractory shock.

Conclusion:

There has been a resurgence of dengue fever with a change in the pattern of presentation during the recent epidemics. Clinical vigilance and awareness regarding the changing epidemic pattern and timely detection of cases are vital to reduce mortality and morbidity due to severe dengue infection.

Keywords: Bleeding, dengue fever, multiorgan failure, shock

INTRODUCTION

Dengue fever is the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease worldwide with an estimated 30-fold increase in incidence over last five decades with an unpredictable clinical course and outcome. An estimated 500,000 people with severe dengue infection require hospitalization annually and 90% of them are children <5 years of age. Without proper treatment, the case fatality rate in severe dengue is more than 20% and with timely intervention, it can be reduced to <1%.[1] The recent epidemics has seen changing pattern of presentation of dengue fever in children especially in the presence of coinfections such as enteric fever and malaria thereby making the clinical decision more difficult and often mislead the physician's initial impression.

Puducherry has not experienced any major epidemics of dengue fever in the past, but since 2012 has seen unprecedented rise in dengue fever cases due to rapid urbanization, population migration and increased number of construction sites, open drains and lack of proper public health measures. This study was undertaken to evaluate clinical profile and outcome of dengue fever in children at a tertiary care hospital in Puducherry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted on confirmed cases of dengue fever admitted in the department of pediatrics at a tertiary care hospital in Puducherry from August 2012 to January 2015. All the data from hospital case records were entered in a structured clinical proforma, and the data were retrospectively analyzed. The case definition, diagnosis, and management for dengue fever were as per the revised World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines 2011. Children were classified as dengue fever without warning signs (D), dengue fever with warning signs (DW) and severe dengue infection. Children with severe plasma leakage, severe organ involvement, and severe thrombocytopenia were categorized as severe dengue infection. The diagnosis was confirmed by NS1 antigen-based ELISA test (J. Mitra Kit, India) or dengue serology for IgM and IgG antibodies (Kit from National vector born disease control program Puducherry and National Institute of virology Pune, India) during the acute phase and convalescent phase of illness. Blood samples were collected from children with a provisional diagnosis of dengue fever and were screened by both NS1 Ag assay and MAC-ELISA. All children suspected of dengue fever in the 1st week of illness who were NS1 Ag negative were retested during the 2nd week of illness. All other relevant and other additional investigations were done as per the clinical course of illness. The study protocol was approved by the Institute Ethics committee of Indira Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute at Puducherry, India.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS for window version 16.0 (SPSS, IL, 233 South Wacker drive, 11th Floor, Chicago, 60606-3412, USA) using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and then analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fishers exact test, where appropriate. Continuous data expressed as mean ± SD, or median (range), were analyzed using Students t-test, analysis of variance-one-way, or Mann-Whitney U-test. Significance was taken at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

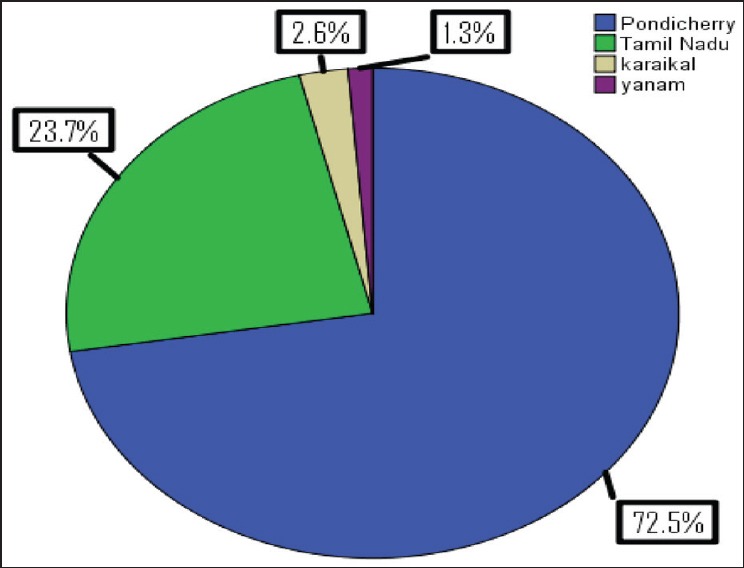

Out of 398 children admitted with dengue fever the diagnosis was confirmed in 261 cases (65.5%). Non-severe dengue was seen in 159 cases (60.9%) and severe dengue infection was seen in 102 cases (39.1%). The mean age of presentation was 6.9 years and 6-12 years was the most commonly affected age group (62.0%). Infants were the least affected sub-group with 7 cases (2.7%). The youngest was a neonate, and the oldest was 12 years of age. The male: female ratio was 1.2:1. The children that were admitted with dengue fever were from Puducherry (76.3%) and Tamil Nadu (23.7%) [Figure 1]. The mean duration of hospital stay was 6.5 (2.7) days.

Figure 1.

Geographical origin of dengue fever cases admitted at a tertiary care hospital in Puducherry

The common clinical presentations included fever (94.6%), conjunctival congestion (89.6%), myalgia (81.9%), coryza (79.7%), headache (75.1%), palmar erythema (62.8%), retro-orbital pain (51.3%), joint pain (28.7%), and rash (17.2%). The common atypical manifestations of dengue fever at admission were lymphadenopathy (52.3%), splenomegaly (20.7%), epigastric tenderness (16.4%) biphasic fever (15.7%), right hypochondriac pain (8.4%), seizures (6.5%), and febrile diarrhea (6.5%), [Table 1]. The mean duration of fever was 4.8 (1.8) days at admission.

Table 1.

Clinical profile of children with dengue fever

The common early warning signs at the time of admission were persistent vomiting (75.1%), liver enlargement (59.8%), cold and clammy extremities (45.2%), peripheral circulatory failure (40.6%), pain abdomen (31.0%), hypotension (29.5%), restlessness (26.4%), giddiness (23.0%), oliguria (18.4%), ascites (6.9%), lethargy (6.3%), pleural effusion (5.0%), and impaired consciousness with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) <8 (2.7%) [Table 1].

Hemorrhagic manifestations were present in 52 children (19.9%), which mainly included skin bleeding (39.2%), gum bleeding (34.6%), epistaxis (23.1%), melena (26.9%), hematemesis (9.6%), intracranial bleed (3.8%), and pulmonary bleed (7.7%). Tourniquet test was positive in 33 cases (12.6%). Melena was the most common form of gastrointestinal (GI) bleed.

Shock was present in 102 cases (39.1%) in children with severe dengue infection and among them significant bleeding was present in only 22 cases (21.6%) and decompensated shock in 16 cases (15.7%). There was difficulty in classifying cases as dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) as all children did not fulfill the four criteria of fever, thrombocytopenia, bleeding, and plasma leakage. The predominant mode of presentation of severe dengue infection was with features of peripheral circulatory failure without spontaneous bleeding. Six children (2.3%) with decompensated shock had fluid refractory shock and required inotropic support.

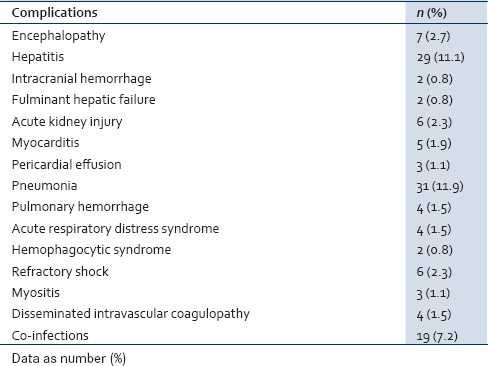

The common complications seen with severe dengue infection were liver dysfunction, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, impaired consciousness (GCS <8), myocarditis, myositis, hemophagocytic syndrome, acute kidney injury (AKI), and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC). Co-infections were seen in 19 cases (7.5%) and among them, enteric fever in 10 cases, malaria in 4 cases, urinary tract infection in 4 cases and one case had acute bacterial meningitis [Table 2].

Table 2.

Complications in severe dengue infection

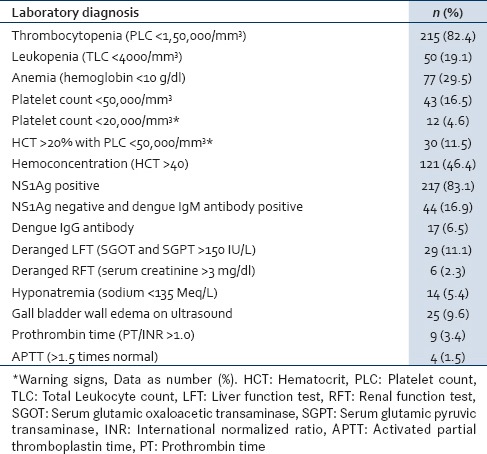

The hematological parameters showed anemia (29.5%), leukopenia (19.1%) and thrombocytopenia in 215 (82.4%) cases. Hemoconcentration was in 46.4% of cases, and the mean hematocrit was 38.9 (4.4). Seven children (2.7%) had platelet count <10,000/mm3, five children (1.9%) were between 10,000 and 20,000/mm3, 31 children (11.9%) were between 20,000 and 50,000/mm3, 58 (22.2%) children had platelet count between 50,000 and 100,000/mm3, 114 (43.7%) children had platelet count between 1 and 1.5 lakh/mm3 and 46 children (17.6%) were >1.5 lakh/mm3). Severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50,000/mm3) was seen in 43 (16.5%) cases and among them 36 (83.7%) cases had severe dengue infection. All children who had platelet count <20,000/mm3 had severe dengue infection. NS1 Ag was negative with IgM antibody positive in 44 cases (16.9%). Dengue IgG antibody was positive in 17 cases (6.5%) and among them, severe dengue infection was seen in 16 cases (94.1%). Disordered coagulation (prolongation of the prothrombin and/or activated partial thromboplastin time) was seen in 13 children (5.0%). Altered liver enzymes were seen in 29 cases (11.1%). Ultrasonography of abdomen showed gallbladder wall edema in severe dengue infection in 25 cases (9.6%) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Laboratory parameters in children with dengue fever

Fifty-two children (19.9%) had spontaneous bleeding and among them, shock was present in 22 children (42.3%). Bleeding manifestations were present in 20 (39.2%), 8 (15.7%), 13 (25.5%) and 11 (21.6%) cases with platelet count between <50,000/mm3, 50,000-100,000/mm3, 1-150,000 and >150,000/mm3, respectively. About 78.8% of children with bleeding had thrombocytopenia, but bleeding manifestations did not always correlate with platelet counts in non-severe dengue infection in comparison to severe dengue infection.

Platelet transfusion was given in 17 children (6.5%) with severe dengue infection and out of them 12 children (70.6%) had a platelet count <20,000/mm3; whereas 5 children (29.4%) had platelet count in the range of 20,000-50,000/mm3. Only those children with significant spontaneous bleeding, shock and with severe thrombocytopenia necessitated platelet transfusion. Apart from platelet transfusion blood transfusion was given in 10 (3.9%) cases, fresh frozen plasma in 6 (2.3%) cases, colloids in 3 (1.2%), intravenous fluids in 96 (37.7%) cases, and inotropes in 5 (1.9%) cases. There were six deaths (2.3%) and out of them four presented with impaired consciousness (66.6%) at admission with GCS <8. The common causes for poor outcome (deaths) were multiorgan failure, encephalopathy, DIC, and refractory shock.

DISCUSSION

Dengue fever is a major public health problem with high morbidity and mortality, and the recent epidemic has shown variable clinical presentations with unpredictable clinical evolution and outcome.[1] In our study, children >6 years were the most commonly affected age group and were more at risk to develop severe dengue infection and similar to the previous studies by Faridi et al., and Wichmann et al.[2,3] However Aggarwal et al., and Gurdeep et al., in their studies showed <6 years of age to be the most common affected age group.[4,5]

In our study, shock was the most common form of presentation in severe dengue infection and was present in 39.1% of cases in comparison to the previous studies by Ratageri et al., Aggarwal et al., where it was present in 22% and 33%, respectively.[4,6] The most common mode of presentation of severe dengue infection was a peripheral circulatory failure without bleeding, and there was difficulty in classifying them as DHF as per 1997 WHO classification as most cases failed to fulfill all the four criteria of fever, hemorrhagic phenomenon, thrombocytopenia, and hemoconcentration. They were sub-classified as dengue fever with bleeding without shock and dengue fever associated with peripheral circulatory failure without bleeding based on the revised 2011 WHO guidelines for dengue fever.[1,7]

Bleeding manifestations were seen in 19.9% of cases and much lower in comparison to the previous studies.[6,7,8,9,10] The most common hemorrhagic manifestations in our study were petechiae and GI bleeding and similar to the previous studies by Ratageri et al., and Rachel et al.[6,8] Melena constituted the most common form of internal bleeding in our study and also in the study by Shah et al.[9] Hematemesis was reported as the most common manifestations in the study by Narayanan et al., whereas epistaxis was most common in the study by Faridi et al.[2,10] The tourniquet test in our study was positive in 12.6% of cases and was much lower compared to the previous studies.[10,11,12,13,14] The tourniquet test did not correlate well with bleeding manifestations or with thrombocytopenia, similar to the finding reported by Wali et al., and Narayanan et al.[10,14] Bleeding manifestations were highly variable and did not always correlate with the platelet counts as it occurred in 21.2% of cases with normal platelet counts.

During the epidemics at Puducherry, primary infection was more common than secondary infection, but 94.1% of cases with secondary infection had severe dengue infection. During secondary infection T-cells become activated due to interactions with infected monocytes which induce plasma leakage by the release of a cascade of cytokines such as interferon-gamma, IL-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) therefore predisposing to DHF and dengue shock syndrome.[3,6] Wichmann et al., in their study showed that secondary infection was significantly associated with the development of severe dengue infection in children.[3]

The most pathognomic feature of dengue is an increase in vascular permeability leading to loss of plasma from blood vessels, which causes hemoconcentration, low blood pressure and shock. This may also be accompanied by a combination of hemostatic abnormalities such as thrombocytopenia, vascular changes, and coagulopathy.[1,7] Hemoconcentration was difficult to interpret in our study due to lack of the availability of preillness hematocrit and with a high prevalence of anemia in the community. However, the change in hematocrit of more than 20% and standard hematocrit cut offs from the previous studies by Gomber et al., and Balasubramanian et al., was used as indicators of hemoconcentration for diagnosing and monitoring severe dengue infection.[11,12,13] There was a poor correlation between thrombocytopenia, bleeding, and plasma leakage in the study as 21.2% of children with bleeding had normal platelet counts and only 24.2% of children with shock had bleeding manifestations. Coagulation profile was deranged in 13 cases (5.1%) signifying the fact that factors other than thrombocytopenia such as platelet dysfunction, consumption coagulopathy, and endothelial dysfunction are responsible for bleeding in dengue fever.[13]

Platelet transfusion was indicated only in children with severe dengue infection with shock with severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50,000/mm3) with significant bleeding and prophylactic platelet transfusion was not given similar to the previous studies.[15,16] Skin bleeds, single episode of epistaxis or mucosal bleed were not given empirical platelet transfusion based on platelet counts.

Children who had features of shock with rising hematocrit, not responding to crystalloids received plasma or colloids whereas with falling hematocrit received a whole blood transfusion.

The classical presentation of dengue fever was not always present in our study. Coryza was one of the common manifestations in our study which is otherwise unusual in dengue fever with very few published reports.[17] Splenomegaly was in 20.7% of cases in our study and is an unusual manifestation of dengue fever. Faridi et al., in their study similarly showed a high percentage (32.4%) of splenomegaly in children with dengue.[2,17] Hemophagocytic syndrome is an unusual manifestation of dengue fever which was present in two cases with very cases reported in the past.[18] Myositis an unusual manifestation was found in two cases in our study. The probable mechanism for myositis is the release of myotoxic cytokines, particularly TNF-a thereby injuring the affected muscle.[19]

Encephalopathy was the most common neurological manifestations in severe dengue infection in our study and 66% of cases with impaired consciousness at admission had a poor outcome. The neurological manifestations in dengue include seizures, encephalopathy, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and rarely Guillain-Barre syndrome.[17] The neurological manifestations are secondary to cerebral hypoperfusion, cerebral edema, direct neurotrophic effect, secondary to hepatic dysfunction and metabolic derangements such as hypoglycemia and hyponatremia as reported in the previous studies.[20,21]

Hepatic dysfunction was seen in 29 children (11.1%) and two children had a fulminant hepatic failure. The etiology of hepatic dysfunction in dengue fever is usually due to direct cytopathic injury, unregulated host immune response, active viral replication, and hypoxia and tissue ischemia due to prolonged shock, hemorrhage, and metabolic acidosis.[22] The other unusual GI complications in the study were pancreatitis, cholecystitis, appendicitis, febrile diarrhea, and parotitis with very few cases reported in the past.[23,24,25,26]

Co-infections were seen in 7.2% of cases, and it is important that they be promptly recognized as they can modify the clinical presentation of dengue fever and can result in missed or delayed diagnosis and treatment. Coexistence of malaria and dengue have been reported to be in the range of 20% to as high as 80%.[7,17,27] The complications associated with poor outcome were acute respiratory distress syndrome, AKI, fluid refractory shock, myocarditis and DIC and similar to the previous studies.[28,29,30] The mortality in our study was 2.3% was much lower compared to the previous studies.[2,4] The common factors could be increased public awareness, better health seeking behavior of parents, early recognition and timely intervention in the study, and change in the epidemic pattern of presentation than in the previous years.

The present study highlights the recent increase in the incidence of dengue fever cases at Puducherry because of lack of proper public health measures. It also highlights the change in the epidemic pattern of presentation with more number of atypical manifestations and lack of classical mode of presentation. Clinical vigilance, awareness and timely intervention are vital to reducing the morbidity and mortality in dengue fever.

There are several limitations to this study. The study is a retrospective analysis of dengue fever cases from a single center and included only those cases that were admitted to the hospital. The diagnosis was confirmed by either dengue NS1 antigen test or dengue serology. Viral isolation and serotype identification and serotype identification was not done in the present study. A large multicentric prospective study including a larger sample size would be ideal.

CONCLUSION

The clinical awareness of the changing pattern of presentation is lacking among health care personnel, especially at primary health centers from where these cases are often referred. Health education regarding the unusual manifestations, changing epidemic trends, early recognition of illness, careful monitoring, timely intervention, and proper public health measures can reduce the morbidity and mortality due to severe dengue infection.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgment

Dr. Vijayalalakshmi Sivapurapu, intensivist for giving critical input to the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. Comprehensive Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever, Revised and Expanded Edition. WHO-SEARO 2011. (SEARO Technical Publication Series No. 60) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faridi MM, Aggarwal A, Kumar M, Sarafrazul A. Clinical and biochemical profile of dengue haemorrhagic fever in children in Delhi. Trop Doct. 2008;38:28–30. doi: 10.1258/td.2007.006158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wichmann O, Hongsiriwon S, Bowonwatanuwong C, Chotivanich K, Sukthana Y, Pukrittayakamee S. Risk factors and clinical features associated with severe dengue infection in adults and children during the 2001 epidemic in Chonburi, Thailand. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:1022–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggarwal A, Chandra J, Aneja S, Patwari AK, Dutta AK. An epidemic of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome in children in Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 1998;35:727–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurdeep SD, Deepak B, Harmesh SB. Clinical profile and outcome of children of dengue hemorrhagic fever in North India. Iran J Pediatr. 2008;18:222–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratageri VH, Shepur TA, Wari PK, Chavan SC, Mujahid IB, Yergolkar PN. Clinical profile and outcome of Dengue fever cases. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:705–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02724083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balasubramanian S, Ramachandran B, Amperayani S. Dengue viral infection in children: A perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:907–12. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-301710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rachel D, Philip R, Philip AZ. A study of clinical profile of dengue fever in Kollam, Kerala, India. Dengue Bull. 2005;29:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah I, Deshpande GC, Tardeja PN. Outbreak of dengue in Mumbai and predictive markers for dengue shock syndrome. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50:301–5. doi: 10.1093/tropej/50.5.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayanan M, Aravind MA, Thilothammal N, Prema R, Sargunam CS, Ramamurty N. Dengue fever epidemic in Chennai: A study of clinical profile and outcome. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:1027–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomber S, Ramachandran VG, Kumar S, Agarwal KN, Gupta P, Gupta P, et al. Hematological observations as diagnostic markers in dengue hemorrhagic fever — A reappraisal. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:477–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balasubramanian S, Anandnathan K, Shivbalan S, Datta M, Amalraj E. Cut-off hematocrit value for hemoconcentration in dengue hemorrhagic fever. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50:123–4. doi: 10.1093/tropej/50.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shivbalan S, Anandnathan K, Balasubramanian S, Datta M, Amalraj E. Predictors of spontaneous bleeding in dengue. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:33–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02725653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wali JP, Biswas A, Aggarwal P, Wig N, Handa R. Validity of tourniquet test in dengue haemorrhagic fever. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:203–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lum LC, Abdel-Latif Mel-A, Goh AY, Chan PW, Lam SK. Preventive transfusion in dengue shock syndrome-is it necessary? J Pediatr. 2003;143:682–4. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chairulfatah A, Setiabudi D, Agoes R, Colebunders R. Thrombocytopenia and platelet transfusions in dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome. WHO Dengue Bull. 2003;27:141–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gulati S, Maheshwari A. Atypical manifestations of dengue. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1087–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramachandran B, Balasubramanian S, Abhishek N, Ravikumar KG, Ramanan AV. Profile of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children in a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:31–5. doi: 10.1007/s13312-011-0020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalita J, Misra UK, Maurya PK, Shankar SK, Mahadevan A. Quantitative electromyography in dengue-associated muscle dysfunction. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;29:468–71. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31826be029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Rivera EJ, Rigau-Pérez JG. Encephalitis and dengue. Lancet. 2002;360:261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamath SR, Ranjit S. Clinical features complications and atypical manifestations of children with severe forms of dengue hemorrhagic fever in South India. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73:889–95. doi: 10.1007/BF02859281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkash O, Almas A, Jafri SM, Hamid S, Akhtar J, Alishah H. Severity of acute hepatitis and its outcome in patients with dengue fever in a tertiary care hospital Karachi, Pakistan (South Asia) BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez GR, Henao-Martinez AF. Dengue hemorrhagic fever complicated by pancreatitis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15:490–2. doi: 10.1016/s1413-8670(11)70235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koh FH, Misli H, Chong VH. Acute acalculous cholecystitis secondary to dengue fever. Brunei Int Med J. 2011;7:45–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helbok R, Dent W, Gattringer K, Innerebner M, Schmutzhard E. Imported dengue fever presenting with febrile diarrhoea: Report of two cases. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116(Suppl 4):58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McFarlane ME, Plummer JM, Leake PA, Powell L, Chand V, Chung S, et al. Dengue fever mimicking acute appendicitis: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:1032–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pancharoen C, Thisyakorn U. Coinfections in dengue patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:81–2. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199801000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lum LC, Thong MK, Cheah YK, Lam SK. Dengue-associated adult respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1995;15:335–9. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1995.11747794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Promphan W, Sopontammarak S, Pruekprasert P, Kajornwattanakul W, Kongpattanayothin A. Dengue myocarditis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35:611–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiwanitkit V. Acute renal failure in the fatal cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever, a summary in Thai death cases. Ren Fail. 2005;27:647. doi: 10.1080/08860220500200916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]