Abstract

Background

The clinical course of gastric lymphoma is heterogeneous and clinical symptoms and some factors have been related to prognosis.

Objective

The present study aims to identify prognostic factors in gastric diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosed and treated in different countries.

Methods

A consecutive series of gastric diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients diagnosed and treated in Brazil, Portugal and Italy, between February 2008 and December 2014 was evaluated.

Results

Of 104 patients, 57 were female and the median age was 69 years (range: 28–88). The distribution of the age-adjusted international prognostic index was 12/95 (13%) high risk, 20/95 (21%) high-intermediate risk and 63/95 (66%) low/low-intermediate risk. Symptoms included abdominal pain (63/74), weight loss (57/73), dysphagia (37/72) and nausea/vomiting (37/72). Bulky disease was found in 24% of the cases, anemia in 33 of 76 patients and bleeding in 22 of 72 patients. The median follow-up time was 25 months (range: 1–77 months), with 1- and 5-year survival rates of 79% and 76%, respectively. The multivariate Cox Regression identified the age-adjusted international prognostic index as a predictor of death (hazard risk: 3.62; 95% confidence interval: 2.21–5.93; p-value <0.0001).

Conclusions

This series identified the age-adjusted international prognostic index as predictive of mortality in patients treated with conventional immunochemotherapy.

Keywords: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Gastric, Prognosis

Introduction

Gastric lymphoma is the most common extra nodal diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) and accounts for 30% of cases of lymphoma in the stomach.1 According to the current WHO lymphoma classification criteria, gastric DLBCLs are classified with or without features of MALT.2 Recent studies revealed that Helicobacter pylori-related gastric DLBCL is a distinct less aggressive entity with greater chemosensitivity, thereby highlighting the heterogeneity of these lymphomas. The clinical presentation and course are also variable with clinical symptoms, laboratorial abnormalities and H. pylori, hepatitis B, and C infections, in addition to classical international prognostic index (IPI) factors having been related to prognosis.3 Different clinical behaviors may reflect distinct unidentified pathogenic mechanisms.4 A better characterization of prognostic factors is required in order to discover new potential disease mechanisms, improve outcomes and individualize treatment approaches. The present study aims to identify prognostic factors in patients with gastric DLBCL diagnosed and treated in different countries by analyzing demographic and clinical characteristics, response to treatment and outcome.

Patients

A retrospective study of 104 consecutive patients with DLBCL diagnosed and treated in hematology centers in Brazil, Italy and Portugal between February 2008 and December 2014 was performed. The inclusion criteria were age >18 years old, lymphoma primarily located in the stomach, with or without the involvement of other intra-abdominal structures and with a confirmed DLBCL histology. All cases were diagnosed according to World Health Organization (WHO) classification criteria.2 Patients with transformation from another type of lymphoma to DLBCL were excluded. Patients were considered H. pylori positive when their histology results were positive.

Data were retrieved from patient's charts with all patients having signed a consent form submitted to the local ethics committee in the diagnosis period. All patients were subjected to a detailed physical evaluation including an investigation of B symptoms (pain, nausea, dysphagia, bleeding, obstruction), routine blood exams (hemoglobin, total and differential leukocyte counts, platelet count and peripheral smear for abnormal/blast cells), biochemical exams [liver function tests, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), β2 microglobulin, albumin, urea, creatinine and uric acid] and serologic investigations for hepatitis B and C and HIV. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations were performed in 95% of the patients. Imaging studies included chest radiographs and/or computed tomography scans and abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scans or ultrasonography. Bulky disease was defined as lesions with a diameter >10 cm. All patients underwent bone marrow aspiration and biopsy as part of the staging procedure. The international prognostic index (IPI), age-adjusted IPI (aaIPI)5 and Ann Arbor stage6, 7 were calculated for each patient.

All patients were treated by systemic chemotherapy mostly consisting of six cycles of the rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) regimen with the intention to cure.8 Patients with residual disease received local radiotherapy. Imaging studies and endoscopic examinations were used to evaluate response.

The influence of the following parameters were evaluated in the response to treatment and survival: LDH, β2 microglobulin, albumin, presence of bulky disease, B symptoms (fever, weight loss, pain, nausea, vomiting), aaIPI, type of treatment (surgery plus chemotherapy, chemotherapy alone), anemia, dysphagia, bleeding, obstruction and presence of H. Pylori at diagnosis. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <12.0 g/dL and elevated LDH levels as >240 U/L.

All patients underwent imaging and follow-up endoscopic examinations (with a biopsy of suspicious lesions) to document treatment response. At the end of chemotherapy, response was classified as complete remission (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) according to the International Working Group criteria.6 Patients who failed initial therapy with R-CHOP (PR, SD and PD) received high-dose chemotherapy together with autologous stem cell transplant. Patients with H. pylori at diagnosis also received antibiotic therapy.

Statistical analysis

Survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. The prognostic value of the different variables for clinical outcome was estimated by univariate and multivariate analyses, applying the Cox proportional hazards regression model. Two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered significant. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 15.0) software (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis.

Results

Clinical and histological features

The clinic pathologic characteristics of the 47 male (45%) and 57 female (55%) patients with gastric DLBCL with a median age of 69 years (range: 28–88 years) are listed in Table 1. The main presenting symptom was abdominal pain (85% of the cases) and the two most common serum alterations were elevations in β2 microglobulin and LDH in 71% and 41% of the cases, respectively. Hypoalbuminemia was found in 26/83 (31%) patients. Bleeding and obstruction were uncommon at presentation and anemia was only present in 43% (33/76) of cases. Among the 45 patients who were tested for H. pylori, 13 were positive. Localized disease (Ann Arbor stages I or II) was present in 46% of the cases, and most patients (67%) were in the low/low intermediate risk group according to the aaIPI; 48% had good performance status [Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score 0].

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at diagnosis.

| Variable | 104 cases |

|---|---|

| Gender (male) – n (%) | 47 (45.2) |

| Age at diagnosis (median, range) | 69 (28–88) |

| Presenting symptoms – n/total (%) | |

| Abdominal pain | 63/74 (85) |

| Weight loss | 57/73 (78) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 37/72 (51) |

| Bleeding | 22/72 (30.5) |

| Anemia – n/total (%) | 33/76 (43) |

| Dysphagia – n/total (%) | 37/72 (51) |

| Helicobacter pylori infection – n/total (%) | 13/45 (29) |

| Hepatitis B (Anti-HBc/HBsAg + )a– n/total (%) | 45/97 (46.4) |

| Stage – n/total (%) | |

| I–II | 48/100 (46) |

| III–IV | 52/100 (54) |

| ECOG – n/total (%) | |

| 0 | 49/101 (48.5) |

| 1–2 | 43/101 (42.6) |

| ≥3 | 09/101 (8.9) |

| Bulky disease (yes) – n/total (%) | 25 (24) |

| B symptoms – n/total (%) | 45/102 (44.1) |

| aaIPI – n/total (%) | |

| 0–1 | 64/95 (67.3) |

| 2–3 | 31/95 (32.7) |

| Hypoalbuminemia – n/total (%) | 26/83 (31) |

| Elevated β2microglobulin – n/total (%) | 57/80 (71.2) |

| Elevated LDH – n/total (%) | 41/99 (41.4) |

| Type of treatment: R-CHOP – n/total (%) | 87/100 (87) |

| Alive – n/total (%) | 82/104 (78.8) |

| Median follow-up n/range (months) censored group | 25 (1–77) |

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score; aaIPI: age-adjusted international prognostic index; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; R-CHOP: Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone.

5 patients with active disease.

Treatment, outcome and prognostic factors

Only 10% of the patients required surgery due to obstruction, perforation or upper gastrointestinal bleeding. In contrast, almost all patients received chemotherapy (87–87/100) and just one patient received local radiotherapy.

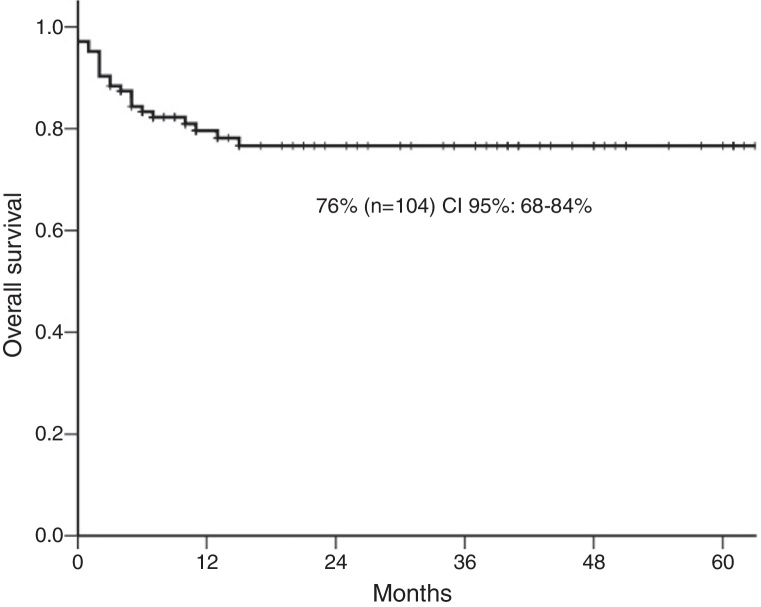

The five-year overall survival was 76% [95% confidence interval (CI): 68–84%] (Figure 1) and 46/71 (64%) achieved complete response. Over a median follow-up of 25 months (range: 1–77 months), the 1- and 5-year survival rates were 79% and 76%, respectively. There were 22 deaths. Only four stage I–II cases (18%) had progressive disease compared to 18 (82%) patients with advanced disease hence, patients with localized lymphoma (I–II) had a significantly higher 5-year survival probability (91%) compared with those with advanced-stage (64%; p-value = 0.003). The 5-year survival of high-risk aaIPI patients was significantly inferior to low-risk patients (91% versus 44%; p-value <0.0001: Table 2).

Figure 1.

The 5-year overall survival.

Table 2.

Five-year survival rate according to clinical features at diagnosis.

| Variable | No. of cases | Five-year follow-up |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Survival rate | p-Valuea | ||

| Ann Arbor stage | ||||

| I-II | 48 | 44 | 91 | 0.003 |

| III-IV | 52 | 35 | 64 | |

| Age-adjusted IPI | ||||

| 0–1 | 63 | 58 | 91 | <0.0001 |

| 2–3 | 32 | 16 | 44 | |

| LDH levels | ||||

| Normal | 58 | 54 | 92 | <0.0001 |

| Abnormal | 41 | 24 | 50 | |

| Anemia (Hb <12 g/dL) | ||||

| No | 43 | 36 | 83 | 0.007 |

| Yes | 33 | 19 | 54 | |

| B symptoms | ||||

| No | 57 | 53 | 91 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 45 | 27 | 56 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | ||||

| No | 35 | 29 | 82 | 0.04 |

| Yes | 37 | 23 | 60 | |

| Bulky disease | ||||

| No | 79 | 66 | 82 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 25 | 16 | 57 | |

IPI: international prognostic index; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

Log-rank test.

In the univariate analysis using Cox regression, several variables were associated to the hazard risk (HR) for death (Table 3). However, in the multivariate analysis just the aaIPI remained as predictive of mortality (HR: 3.62; 95% CI: 2.21–5.93; p-value <0.0001).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of hazard risk for death.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulky disease | 2.34 | 0.99–5.54 | 0.05 |

| Hypoalbumenia | 3.08 | 1.27–7.47 | 0.01 |

| Stage III–IV | 4.67 | 1.57–13.9 | 0.006 |

| BM involvement | 4.07 | 1.55–10.7 | 0.004 |

| B symptoms | 6.21 | 2.09–18.4 | 0.001 |

| LDH abnormal | 8.89 | 2.95–26.8 | <0.0001 |

| aaIPI | 3.62 | 2.21–5.93 | <0.0001 |

HR: hazard risk; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; BM: bone marrow; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; aaIPI: age-adjusted international prognostic index.

Significance defined as p-values <0.05.

Discussion

An unexpected high incidence of primary gastric DLBCL was found in this multicenter series of patients treated at tertiary care centers. Advanced stage was present in half of the patients and one third had high-risk aaIPI. Regardless of the prevalence of factors considered to be associated with poor prognosis (advanced stage, B symptoms, bulky disease, elevated LDH and high-risk aaIPI), the outcomes compared favorably with registry data.9

The majority of the published data showed that primary gastric DLBCL predominates in men.10, 11 Interestingly, in this cohort of Brazilian and European patients, a slightly higher incidence was observed in women. Most patients had advanced stage disease and a high-risk aaIPI at diagnosis. The median age was 69 years old, ranging between 28 and 88 years, which is in agreement with others studies.12, 13 In nodal DLBCL, an age higher than 60 years is a confirmed poor prognostic factor. Similar to another study, no relationship was found between age and survival.14

The main clinical presentations of the disease were non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and weight loss. Some authors identified abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding and nausea/vomiting as the most common symptoms in large cohorts of patients.12, 15 The results of this study were similar with 85% of evaluable patients developing abdominal pain, 75% had weight loss and 51% had nausea. Anemia, detected in 43% of the evaluable patients, was also common. In general, the clinical manifestations of gastric lymphoma are non-specific which may result in a delayed diagnosis.

Low albumin levels have been suggested as an important predictor of survival in elderly lymphoma patients and particularly in gastric DLBCL.16 In this study, 31% of the patients had hypoalbuminemia, nevertheless, this hypothesis was not confirmed in the multivariate analysis.

Thirteen of the 45 patients who were tested for H. pylori were positive. This is not a high incidence, but H. pylori infection plays a role in DLBCL.17 Hence, these patients were also treated for H. pylori infection.

Univariate analysis confirmed published data regarding the prognostic impact of the aaIPI, ECOG, elevated DHL, advanced stage, B symptoms, anemia, bulky disease and albumin levels.10, 15 Nevertheless, multivariate analysis showed that only aaIPI retained its significance as an independent predictor of outcome. Almost one quarter of the patients had bulky disease at diagnosis and this turned out to be a negative impact factor, and although rituximab decreased the adverse prognostic value of bulky disease, it did not eliminate the effect completely.18

One of the limitations of this study is its retrospective design however this was the best way to get a relevant number of the patients with similar clinical features. The aaIPI was identified as a predictor of survival in patients treated with conventional immunochemotherapy.

Authors’ contributions

M.T. Delamain, M.G. Da Silva, J. Desterro and S. Luminari conceived and designed all study. M.G. Da Silva, J. Desterro, E.C.M. Miranda, A. Fedina, and C.S. Chiattone were responsible for the data acquisition. E.C.M. Miranda applied all analyses. M.T. Delamain, M.G. Da Silva, J. Desterro, and S. Luminari, F. Merli, C.S. Chiattone, K.B. Pagnano, M. Federico, C.A. De Souza were responsible for interpretation, manuscript drafting and critical revision. All authors approved the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.D’Amore F., Brincker H., Gronbaek K., Thorling K., Pedersen M., Jensen M.K. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(8):1673–1684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.8.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H. fourth ed. IARC Press; Lyon: 2008. WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen S., Schory P.C. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of primary gastrointestinal lymphomas. Up to Date. 2001;9:2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medina-Franco H., Germes S.S., Maldonado C.L. Prognostic factors in primary gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(8):2239–2245. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sehn L.H., Berry B., Chhanabhai M., Fitzgerald C., Gill K., Hoskinss P. The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood. 2007;109(5):1857–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheson B.D., Horning S.J., Coiffier B., Shipp M.A., Fisher R.I., Connors J.M. Report of an International Workshop to standardized response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2000:18(11);2351] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carbone P.P., Kaplan H.S., Musshoff K., Smithers D.W., Tubiana M. Report of the Committee of Hodgkin's Disease Staging classification. Cancer Res. 1971;31(11):1860–1861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sehn L.H., Donaldson J., Chhanabhai M., Fitzgerald C., Kill K., Klasa R. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5027–5033. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castro F.A., Jansen L., Krilaviciute A., Katalinic A., Pulte D., Sirri E. Survival of patients with gastric lymphoma in Germany and in the United States. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(10):1485–1491. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotaru I., Gãman G.D., Stãnescu C., Gãman A.M. Evaluation of parameters with potential prognosis impact in patients with primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (PG-DLBCL) Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55(1):15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang J., Jiang W., Xu R., Huang H., Lv Y., Xia Z. Primary gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Chinese patients: clinical characteristics and prognostic factors. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:358. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radić-Kristo D., Planinc-Peraica A., Ostojić S., Vrhovac R., Kardum-Skelin I., Jaksić B. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma in adults: clinicopathologic and survival characteristics. Coll Antropol. 2010;34(2):413–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreri A.J., Montalban C. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the stomach. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosseini S., Dehghan P. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the stomach: clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic factors in Iranian patients. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2014;7(Fall (4)):219–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding D., Pei W., Chen W., Zuo Y., Ren S. Analysis of clinical characteristics, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of 46 patients with primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:259–264. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chihara D., Oki Y., Ine S., Kato H., Onoda H., Taji H. Primary gastric diffuse large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL): analyses of prognostic factors and value of pretreatment FDG-PET scan. Eur J Haematol. 2010;84(6):493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo S.H., Yeh K.H., Wu M.S., Lin C.W., Hsu P.N., Wang H.P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy is effective in the treatment of early-stage H. pylori-positive gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2012;119(21):4838–4844. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-404194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfreundschuh M., Ho A., Cavallin-Stahl E., Wolf M., Pettengell R., Vasova I. Prognostic significance of maximum tumor (bulk) diameter in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma treated with CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab: an exploratory analysis of the MabThera International Trial Group (MInT) study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(5):435–444. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]