Abstract

Developing new methods for chemotherapy drug delivery has become a topic of great concern. Vinca alkaloids are among the most widely used chemotherapy reagents for tumor therapy; however, their side effects are particularly problematic for many medical doctors. To reduce the toxicity and enhance the therapeutic efficiency of vinca alkaloids, many researchers have developed strategies such as using liposome-entrapped drugs, chemical- or peptide-modified drugs, polymeric packaging drugs, and chemotherapy drug combinations. This review mainly focuses on the development of a vinca alkaloid drug delivery system and the combination therapy. Five vinca alkaloids (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, vinorelbine, vindesine, and vinflunine) are reviewed.

Keywords: Vinca alkaloids, Drug delivery systems, Combination therapy, Vincristine, Vinblastine, Vinorelbine, Vindesine, Vinflunine, Vinpocetine

1. Introduction

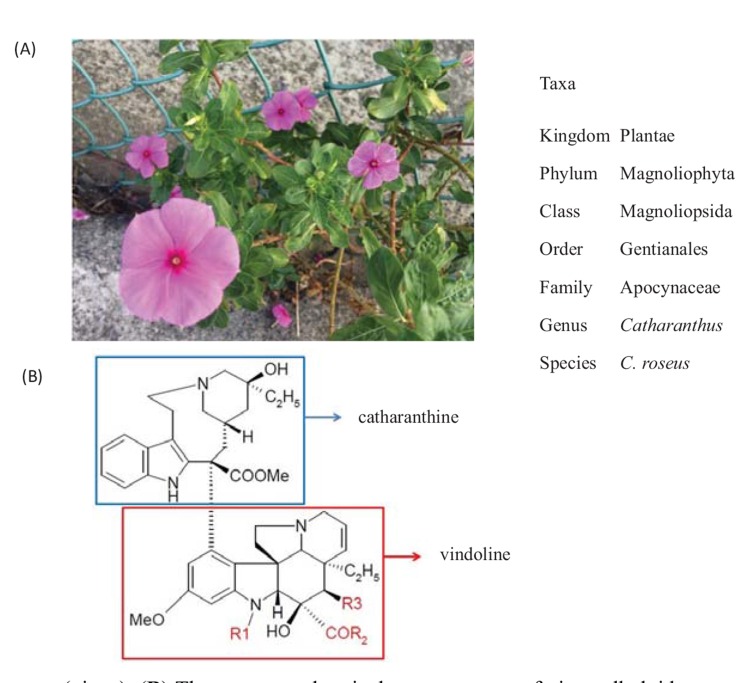

Catharanthus roseus (C. roseus; Fig. 1), commonly known as the Madagascar rosy periwinkle or vinca, is a species of herbaceous, perennial tropical plant that grows approximately 1 m tall. Its leaves range from oval to oblong in shape, 2.5 cm to 9 cm long and 1 cm to 3.5 cm broad, and are glossy, green, and hairless, with a pale midrib and a short petiole 1 cm to 1.8 cm long. The flowers vary in color from white to dark pink with a dark red center, and have a basal tube 2.5 cm to 3 cm long and a corolla 2 cm to 5 cm in diameter with 5 petal-like lobes.[1] Vincas have long been cultivated for medicinal purposes. For example, practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine use its extracts to fight against numerous diseases, including diabetes, malaria, hypertension, empyrosis, sores, and Hodgkin's lymphoma.[2] European herbalists created folk remedies with vinca extract for use in conditions that varied from headaches to diabetes. Vincamine, the active compound, and its closely related semi-synthetic derivative widely used as a medicinal agent, ethylapovincaminate or vinpocetine, have vasodilating, blood thinning, hypoglycemic, and memory-enhancing properties.[3, 4] Ayurvedic physicians in India use vinca flowers to brew tea for the external treatment of skin problems such as dermatitis, eczema, and acne.[3, 4] In addition, the juice of the leaves can be applied externally to relieve wasp stings and hyperlipidemia.[5]

Fig. (1).

(A) Catharanthus roseus (vinca). (B) The common chemical core structure of vinca alkaloids, generated by joining 2 alkaloids, catharanthine and vindoline. The substitute group R1 of vinblastin, vindesine, vinorelbine, and vinflunine is methyl, and that of vincristine is formyl. The substitute groups R2 and R3 of vinblastin, vincristine, vinorelbine, and vinflunine are methoxy and acetoxy, whereas those of vindesine are amine and hydroxy. The hydroxylation and alkylation site of catharanthine in vinflunine is modified with ethylidene difluoride.

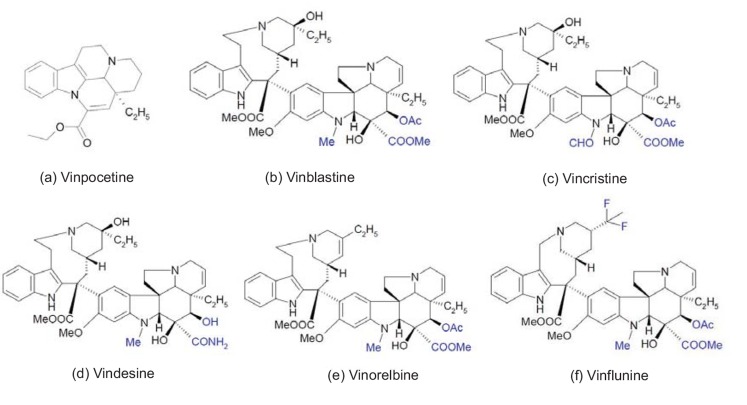

Vinca alkaloids have exhibited significant antineoplastic activity against numerous cell types.[3, 4] Five major vinca alkaloids, vincristine, vinblastine, vinorelbine, vindesine, vinflunine, and one of the vincamine, vinpocetine (Fig. 2), have clinical uses (however, in the United States, only vincristine, vinblastine, and vinorelbine have been approved for clinical use [6]). Researchers have isolated vinblastine in 1958, [7] and later synthesized vincristine, vinorelbine, and vinpocetine, defining them as the vinca alkaloid derivatives.[8, 9] Vinflunine is a new synthetic vinca alkaloid that has been approved in Europe for treating second-line transitional cell urothelium carcinoma.[10] Vinca alkaloids are anticarcinogenic agents that act by binding to intracellular tubulin, which is used in many chemotherapeutic regimens for a wide variety of cancers. The alkaloids inhibit cell division by blocking mitosis, and also inhibit purine and RNA synthesis by killing rapidly dividing cells. Vinca alkaloids are available under the trade names Oncovin® (vincristine), Velban® (vinblastine), and Navelbine® (vinorelbine). Although vinca alkaloids are common drugs used to treat cancers, their side effects cause serious problems. Vinca alkaloids are cytotoxic drugs available by prescription only, and are usually administered through intravenous injection or infusion. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, headaches, dizziness, peripheral neuropathy, hoarseness, ataxia, dysphagia, urinary retention, constipation, diarrhea, and bone marrow suppression. In addition, vinca alkaloids are susceptible to multidrug resistance. [11] The risk of side effects and multidrug resistance has limited the development of vinca alkaloids for clinical applications.

Fig. (2).

The chemical structures of alkaloid vincamine and 5 major vinca alkaloids. The vinca alkaloids’ variations of substitute groups between them are highlighted in blue to clearly distinguish the differences.

To solve these problems, researchers have developed numerous strategies, such as using liposome-entrapped drugs, chemically modified drugs, and polymeric packaging drugs, to reduce the toxicity and enhance the therapeutic efficiency of vinca alkaloids.[10,12-14] Gregoriadis first proposed the concept of liposome-entrapped drugs[12, 15, 16]; currently, various brands, such as DaunoXome®, Myocet®, DOXIL®, Lipo-Dox®, and Marqibo®,[12] are used in clinical applications. Many liposome products, such as SPI-077, CPX-351, MM-398, and MM-302, [12] are still tested in clinical trials. Another strategy for reducing chemotherapy toxicity involves using chemically modified drugs,

which can target specific proteins that tumors might overexpress, such as folic acid receptors, tyrosine kinases, and tumor neovascular markers. Such as folic acid conjugated drugs, thymidine conjugated drugs, and peptides for tumor neovasculature-targeting conjugated drugs. [17-20] Polymer-entrapped drugs reduce the side effects of chemotherapy. Many studies show that after packing (in which chemotherapy drugs are loaded into poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)(PLGA), aldehyde poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(lactide), and methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)(PEG)–poly(lactide) (MPEG–PLA) copolymers, the polymer drug delivery systems can enhance the therapeutic effect of cancer chemotherapy.[2, 17, 18, 21, 22] In addition, previous research has indicated that chemotherapy drug combinations are a promising strategy for reducing the side effects of chemotherapy [20].

Vinca alkaloids are one of the most commonly used anticancer drugs. Various topics about vinca alkaloids have been reviewed. [23-33] However, descriptions of the vinca alkaloid delivery system are limited. In this article, we review the developments in drug delivery systems and combination therapies for vinca alkaloids.

2. Vincristine

Vincristine, a natural vinca alkaloid, was first derived from the leaves of C. roseus[34-36] and has been used in tumor therapy since the 1960s as a cell cycle-specific (M-phase) antineoplastic agent.[18, 29, 34-38] The alkaloid can bind to tubulin, causing microtubule depolymerization, metaphase arrest, and apoptosis in cells undergoing mitosis.[18, 34, 35, 39, 40] Vincristine have been used for many years by clinics to treat malignancies including philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lyphoblastic leukemia,[22, 41] B-cell lymphoma,[42, 43] metastatic melanoma,[38] estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer,[40] glioma,[44, 45] colorectal cancer,[21] non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,[39, 46] Hodgkin’s lymphoma, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, multiple myeloma, and Wilms’ tumor.[2] However, its applications are restricted by severely neurotoxic side effects.

Determining how to transport vincristine to the specific target without damaging other organs is a critical topic of concern. [47] Table 1 summarizes a few drug delivery systems that have been invented. For example, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a natural protectant for the central nervous system; however, it also limits the efficacy of many systemically administered agents.[34] Aboutaleb et al. developed a new method that incorporates the freely water-soluble vincristine sulfate into solid lipid nanoparticles with the assistance of dextran sulfate. Their formulation exhibits comparable cytotoxic effects compared to nonpackaged drugs for use against MDA-MB-231 cells.[37] Previous researchers have proved that cetyl palmitate solid lipid nanoparticles is a potential material for vincristine drug delivery to the brain that enhanced the half-life and concentration in plasma and brain tissue by injecting the particles into a rat-tail vein.[37] Folic acid/peptide/PEG PLGA composite particles are another material demonstrating excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical strength that has been used in drug delivery applications for many years. [48-51] Surface modification and the bioconjugate of PLGA composite beads with folic acid, cell-penetrating peptide, and PEG are used to target and enhance drug uptake in MCF-7 cells.[18] In addition, self-assembled dextran sulphate-PLGA hybrid nanoparticles encapsulating vincristine have been utilized to overcome multidrug resistance tumors; this formulation can sustain releasing vincristine. The uptake efficiency of MCF-7/Adr is significantly increased (12.4-fold higher).[52] Multifunctional composite core-shell particles (comprised of a PLGA core, a hydrophilic PEG shell, phosphatidylserine electrostatic complex, and an amphiphilic lipid monolayer on the core surface) have been developed and exhibit sustained-release characteristics in vitro and in vivo, and greater uptake efficiency (12.6-fold) and toxicity (36.5-fold) to MCF-7/Adr cells.[53]

Table 1.

Vincristine delivery systems.

| Material | Formula | Size | Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA | folic acid and peptide conjugated PLGA–PEG bifunctional nanoparticles | ~250 nm | MCF-7 cell | [18] |

| peptide R7-conjugated PLGA-PEG-folate | - | MCF-7; MCF-7/Adr cell | [59] | |

| dextran sulphate-PLGA hybrid nanoparticles | ~128 nm | MCF-7/Adr cell; rat | [52] | |

| multifunctional nanoassemblies (PLGA-PEG-PS) | ~95 nm | MCF-7/Adr cell | [53] | |

| PLGA loaded collagen-chitosan complex film | - | - | [60] | |

| drug-incorporated PLGA microspheres embedded in thermoreversible gelation polymer (drug/PLGA/TGP) | 20~49 μm | C6 rat glioma cell; rat | [45] | |

| PEG | folic acid and peptide conjugated PLGA–PEG bifunctional nanoparticles | ~250 nm | MCF-7 cell | [18] |

| peptide R7-conjugated PLGA-PEG-folate | - | MCF-7; MCF-7/Adr cell | [59] | |

| multifunctional nanoassemblies (PLGA-PEG-PS) | ~95 nm | MCF-7/Adr cell | [53] | |

| F56 peptide conjugated nanoparticles (F56/PEG-PLA/MPEG-PLA) | ~153 nm | CT-26 lung metastasis mice; HUVEC | [21] | |

| microemulsions composed of PEG-lipid/oleic acid/vitamin E/cholesterol | 137~139nm | in M5076 tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice |

[61] | |

| telodendrimer (PEG(5k)-Cys(4)-L(8)-CA(8)) with disulfide cross-linked micelles | ~ 16 nm | in lymphoma bearing mice | [42] | |

| ESM/cholesterol/PEG2000-ceramide/quercetin | ∼130 nm | MDA-MB-231 cell; in mice | [37] | |

| distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine-PEG liposomes (DSPE-PEG) | ~100 nm | RM-1 prostate tumor cell; DBA/2 mice; BDF1 mice | [35] | |

| egg sphingomyelin/cholesterol/PEG2000-ceramide/quercetin | ∼130 nm | JIMT-1 human breast-cancer cell; in mice | [62] | |

| phospholipon100H/cholesterol/PEG2000 | 110~130 nm | athymic mice | [63] | |

| Dextran sulphate | dextran sulfate complex solid lipid nanoparticles | 100~169 nm | MDA-MB-231 cell; rat | [37] |

| dextran sulphate-PLGA hybrid nanoparticles | ~128 nm | MCF-7/Adr cell; rat | [52] | |

| Oleic acid | vincristine–oleic acid ion-pair complex loaded submicron emulsion | 145~170nm | MCF-7 cell; rat | [36] |

| microemulsions composed of PEG-lipid/oleic acid/vitamin E/cholesterol | 137~139nm | in M5076 tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice |

[61] | |

| Liposome | vincristine sulfate liposome injection (Marqibo®) | ~100 nm | Rag2M mice; non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; glioblastoma; mantle cell lymphoma; beagle dog | [22, 30, 31, 39-41, 43, 45, 46, 64-67] |

| distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine-PEG liposomes (DSPE-PEG) | ~100 nm | RM-1 prostate tumor cell; DBA/2 mice; BDF1 mice | [35] | |

| sphingomyelin and cholesterol liposomes | - | diffuse large B cell lymphoma; B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | [32] | |

| egg sphingomyelin/cholesterol/PEG2000-ceramide/quercetin | ∼130 nm | JIMT-1 human breast-cancer cell; in mice | [62] | |

| phospholipon100H/cholesterol/PEG2000 | 110~130 nm | athymic mice | [63] | |

| Chitosan | PLGA loaded collagen-chitosan complex film | - | - | [60] |

| PBCA | poly (butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles modified superficially with Pluronic® F-127 | - | raji cell; mice | [68] |

| Transfersomes | vincristine loaded transfersomes | ~63 nm | in rat | [69] |

| Niosome | niosomal vincristine | - | in rat | [70, 71] |

Liposomes, spherical in shape, are composed of phospholipid bilayers that can encapsulate and deliver hydrophilic and lipophilic molecules.[54-58] Because they resemble cell membranes with non-immunogenicity, highly biocompatibility, and safe, liposomes have been widely used in drug delivery systems.[41] Liposomal vincristine (Marqibo®), which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has been widely applied in many cancers therapies [22, 39-41, 43, 45, 46]. Table 1 lists the advantages of drug delivery systems, including half-life, uptake, concentration enhancement, and sustained-release characteristics. The size of the composite beads should in nanometer, which can enhance therapeutic efficiency. [59]

3. Vinblastine

Vinblastine is a mitotic inhibitor that has been used in the clinical treatment of leukemia, non-Hodgkin’s disease, Hodgkin’s disease, breast cancers such as breast carcinoma, Wilm’s tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, small-cell lung cancer, testicular carcinoma, and germ cell tumors.[6, 72-74] Vinblastine restrains not only the tumor growth, but malignant angiogenesis,[6, 72-76] and can bind specifically to tubulin, inhibiting its polymerization and the subsequent association of microtubules. Side-effects of vinblastine consist of toxicity to white blood cells, nausea, vomiting, constipation, dyspnea, chest or tumor pain, wheezing, fever, and rarely, antidiuretic hormone secretion. [6]

Table 2 summarizes some of the several surface modification, bioconjugate, and drug delivery systems of vinblastine that enhance the therapeutic effects and lower toxicity. For example, thymidine modified vinblastine, forms a thymidine-vinblastine bioconjugate, a bifunctional molecule comprising a microtubule-binding agent and a substrate for a disease-associated kinase. The results showed that fluorescent conjugates of thymidine accumulate in cells in a manner consistent with kinase-mediated trapping, the first account of this type of trapping of cancer therapeutics.[19] In addition, folic acid-vinblastine conjugates have been fabricated to specifically bind to folate receptor overexpressed tumors.[77] Incorporated magnetic nanomaterials in cationic liposomes for tumor vascular targeting have been disclosed. These composite particles can kill vessel cells specifically. [74, 78]

Table 2.

Vinblastine delivery systems.

| Material | Formula | Size | Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymidine conjugate | vinblastine-thymidine (Covalent Bond) | Molecular level | K562, HT29, and MCF7 cell lines | [19] |

| Folic acid and folate | desacetylvinblastine monohydrazide attached to a hydrophilic folic acid-peptide compound(EC145) (Covalent Bond) | Molecular level | novel synthesis study and the clinical pharmacokinetics and exposure-toxicity relationship study | [77, 79] |

| vinblastine-folate by carbohydrate-based synthetic approach(EC0905) (Covalent Bond) | Molecular level | novel synthesis study and invasive urothelial carcinoma in dogs | [80-82] | |

| vinblastine sulfate-loaded folate-conjugated bovine serumalbumin nanoparticles | ~150 nm | novel synthesis study | [83] | |

| PLGA | vinblastine encapsulated in PLGA microspheres | 46 μm | pharmacokinetics study | [84] |

| Liposome | anti-HER2 immunoliposomal vinblastine | 99.5 nm | SKBR-3 and BT474-M2 in vitro and BT474-M2 xenografts in mice | [85] |

| magnetic cationic liposomes packaged vinblastine | 105-267 nm | B16-F10 in vitro and in mice | [74, 78] | |

| anionic liposomes (DPPC and DPPG with cholesterol) | - | six cell lines tested | [86] | |

| new liposome formulations (wheat germ lipids) | - | against nine human leukemic cell lines | [87] | |

| multi-lamellar vesicle-liposomes | - | UV-2237M murine fibrosarcoma and its Adriamycin (ADR)-selected multidrug resistant (MDR) variants. | [88] |

4. Vinorelbine

Vinorelbine is a semi-synthetic vinca alkaloid with a wide antitumor spectrum of activity, especially active in advanced breast cancer and advanced/metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Compared with vincristine and vinblastine, vinorelbine is more active and relatively less neurotoxic.[89-92] An injectable form of vinorelbine (Navelbine® IV, Medicament, France) developed by Pierre Fabre is now widely used in clinics. Because vinorelbine is well known to cause venous irritation and phlebitis when directly administered intravenously, [89-92] new drug delivery systems are urgently required. [89-93]

Table 3 outlines a few of the vinorelbine delivery systems. To reduce the severe intravenous formulation side-effects of vinorelbine, a lipid microsphere vehicle has been developed.[89] Takenaga first developed a lipid microsphere in 1996, demonstrating that it can act as a antitumor agent

Table 3.

Vinorelbine delivery system.

| Material | Formula | Size | Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid microsphere | vinorelbine lipid microsphere vehicle | ~180 nm | reduce inflammation in ear-rim auricular vein injection rabbit | [89] |

| Lipid emulsion | vinorebine incorporated in lipid emulsion | ~165 nm | A549, Heps G2 and BCAP-37 in mice | [90] |

| Liposome | temperature-sensitive liposome packed vinorebine | ~100 nm | Lewis lung carcinoma in mice | [96] |

| 111In-labeled VNB-PEGylated liposomes | - | C26/tk-luc colon carcinoma in mice | [100] | |

| PEGylated liposome formulations | - | drug loading and pharmacokinetic studies;HT-29、BT-474 and Calu-3 in mice | [92, 101] | |

| immuno-liposomes using anti-CD166 scFv | - | Du-145, PC3, and LNCaP in vitro | [102] | |

| PE | micelles packed vinorebine (PEG-PE) | ~14 nm | 4T1 tumor in mice | [99] |

| PEG | aptamer-nanoparticle (AP-PLGA-PEG) | <200 nm | MDA-MB-231 BC cells and MCF-10A in vitro | [103] |

| PEGylated solid lipid nanoparticles | 180-250 nm | MCF-7 and A549 cells in vitro | [104] | |

| 111In-labeled VNB-PEGylated liposomes | - | C26/tk-luc colon carcinoma in mice | [100] | |

| PEGylated liposome formulations | - | drug loading and pharmacokinetic studies;HT-29、BT-474 and Calu-3 in mice | [92, 101] | |

| micelles packed vinorebine (PEG-PE) | - | 4T1 cells in vitro | [105] | |

| PLGA | aptamer-nanoparticle (AP-PLGA-PEG) | <200 nm | MDA-MB-231 BC cells and MCF-10A in vitro | [103] |

| Lecithin E80 and oleic acid | solid lipid nanoparticles | 150-350 nm | MCF-7 in vitro | [106] |

carrier and reduce toxicity in mice.[94] Vinorelbine lipid microsphere vehicles reduce venous inflammation and have pharmacokinetics in vivo that are similar to the current vinorelbine aqueous injection.[89] In 2008, Xu et al. developed a lipid emulsion formula, another strategy for reducing inflammation in local injection sites. [95] Vinorelbine incorporated in lipid emulsion significantly reduced the decreases in red and white blood cells. In addition, the potential formula of a vinorelbine-phospholipid complex can dramatically reduce injection irritation and maintain an antitumor effect in lung and breast cancer in mouse models.[90] Temperature-sensitive liposome-packed vinorelbine can inhibit tumor growth much more efficiently than free vinorelbine after only 30 minutes of hyperthermia.[96] The PEG-phosphatidylethanolamine micelle containing hydrophobic and hydrophilic position is another widly used drug delivery system.[97-99] Lei et al. observed that the PEG-phosphatidylethanolamine micelle (14.5 nm in diameter) accumulated in the lymph node and reduced metastasis rate in 4T1 tumor bearing mice.[99]

5. Vindesine and vinflunine

Vindesine, desacetyl-vinblastine-amide, is a semisynthetic vinca alkaloid with effects similar to those of vinblastine.[6, 107] Vindesine inhibits net tubulin addition at the assembly ends of microtubules and treats pediatric solid tumors; malignant melanoma; blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia; acute lymphocytic leukemia; metastatic colorectal; and breast, renal, and esophageal carcinomas.[6, 108, 109] Although vindesine is useful for treating many types of cancer, it is not approved by the FDA.[6] Vinflunine, a semi-synthetic vinca alkaloid, is currently being clinically evaluated.[6, 110] Both second-generation vinca alkaloid, vinorelbine, and third-generation compound vinflunine have shown promising results in cancer therapy.[110] Vinflunine is emerging as an effective anticancer agent because it is less neurotoxic than vinorelbine and has superior antitumour activity (preclinical) compared to that of other vinca alkaloids. Although vindesine and vinflunine are promising antitumor agents used clinically, research on related drug delivery systems is limited.

6. Combination therapy

Combination therapy is a promising strategy for reducing the side effects of vinca alkaloids, [20] which are combined with other chemotherapy drugs to enhance antitumor effects (Table 4). Drugs are often administered simultaneously as a cocktail or sequentially to maximize their therapeutic impact.[111] Vincristine combined with cyclophosphamide and prednisone is called CVP, which is used as a first-line therapy for follicular B-cell lymphoma.[111-114] A combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, called CHOP, is used in front-line therapy to treat patients with either follicular or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.[111-114] Rituximab combined with CVP or CHOP creates another first-line treatment for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.[111-114]

Table 4.

Combination therapy of vinca alkaloids for cancer treatments

| Formula | Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone) | first-line therapy for follicular B-cell lymphoma | [111-114] |

| CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) | front line therapy for follicular or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | [111-114] |

| rituximab combine with CVP or CHOP | first-line therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma | [111-114] |

| VCRT (vinblastine, cisplatin and radiation therapy) | treat IIIA and IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer | [115] |

| CISCA/VB (cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vinblastine and bleomycin) | non-seminomatous germ-cell tumors | [116] |

| ABVD (doxorubicin, bleoycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine) | standard chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma | [117] |

| vinorelbine and cisplatin | adjuvant chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer | [118-121] |

| a thoracic radiation scheme, vinorelbine and cisplatin | stage III A and stage III B non-small cell lung cancer | [122] |

Vinblastine can be used to treat different kinds of tumors when in combination with other chemotherapy agents. Vinblastine, cisplatin, and radiation therapy, known as VCRT, is used to treat IIIA and IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer.[115] Cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vinblastine, and bleomycin, or CISCA/VB, is used in patients with disseminated nonseminomatous germ-cell tumors.[116] Combination therapy with doxorubicin, bleoycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine is a standard chemotherapy regimen for Hodgkin’s lymphoma.[117]

Vinorelbine combination chemotherapy is also used to treat various cancers. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin is used for non-small-cell lung cancer. [118-121] A novel thoracic radiation scheme was developed in 2014 that combined vinorelbine and cisplatin; patients with stage III A and stage III B non-small-cell lung cancer subjected to this type of chemotherapy exhibited positive results. [122]

Conclusion

Vinca alkaloids are a class of anticancer drugs used as chemotherapy reagents for many kinds of tumors; however, their side effects restrict application. Drug delivery systems and combination therapy could reduce these side effects. This paper presents a review of drug delivery systems, including liposome-entrapped drugs, chemical- or peptide-modified drugs, polymeric packaging drugs, and chemotherapy drug combination therapy. Liposome-entrapped drugs have protective effects, harmless to tissues at the injection site, and can also enhance the half-life of drugs. Target specific antigens, such as HER-2 receptor or CD166, were modified to the liposome, which enhanced the binding ability and reduced toxicity to other organs. Combination therapy could reduce the side effects; we have described various combinations such as CVP, CHOP, and VCRT. Although vindesine and vinflunine are promising vinca alkaloids, but descriptions of their drug delivery systems are few. Based on the successful drug delivery systems with vincristine, vinblastine, and vinorelbine, researchers can develop new formulas for vindesine and vinflunine in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTs

This work was financially supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Catharanthus roseus. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catharanthus_roseus http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catharanthus_ roseus.

- 2.Wang C.H., Wang G.C., Wang Y., Zhang X.Q., Huang X.J., Zhang D.M., Chen M.F., Ye W.C. Cytotoxic dimeric indole alkaloids from Catharanthus roseus. Fitoterapia. 2012;83(4):765–769. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nayak B.S., Anderson M., Pinto Pereira L.M. Evaluation of wound-healing potential of Catharanthus roseus leaf extract in rats. Fitoterapia. 2007;78(7-8):540–544. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nayak B.S., Pinto Pereira L.M. Catharanthus roseus flower extract has wound-healing activity in Sprague Dawley rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2006;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel Y., Vadgama V., Baxi S. Chandrabhanu; Tripathi, B., Evaluation of hypolipidemic activity of leaf juice of Catharanthus roseus (Linn.) G. Donn. in guinea pigs. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2011;68(6):927–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moudi M., Go R., Yien C.Y., Nazre M. Vinca Alkaloids. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013;4(11):1231–1235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noble R.L., Beer C.T., Cutts J.H. Further biological activities of vinca leukoblastine - an alkaloid isolated from Vinca rosea (L.). Biochem. Pharmacol. 1958;1:347–348. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svoboda G.H. Alkaloids of Vinca rosea Linn. IX. Extraction and characterisation of leurosidine and leucocristine. Lloyda. 1961;24:173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson S.A., Harper P., Hortobagyi G.N., Pouillart P. Vinorelbine: an overview. Cancer Treat. Rev. 1996;22(2):127–142. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(96)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sen K., Mandal M. Second generation liposomal cancer therapeutics: transition from laboratory to clinic. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;448(1):28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueda K., Cardarelli C., Gottesman M.M., Pastan I. Expression of a full-length cDNA for the human “MDR1” gene confers resistance to colchicine, doxorubicin, and vinblastine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84(9):3004–3008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen T.M., Cullis P.R. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013;65(1):36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torchilin V. Tumor delivery of macromolecular drugs based on the EPR effect. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011;63(3):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang M., Shi X. Folic acid-modified dendrimer–DOX conjugates for targeting cancer chemotherapy. J. Control. Release. 2013;172(1):e55–e56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregoriadis G. The carrier potential of liposomes in biology and medicine (second of two parts). N. Engl. J. Med. 1976;295(14):765–770. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197609302951406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregoriadis G. The carrier potential of liposomes in biology and medicine (first of two parts). N. Engl. J. Med. 1976;295(13):704–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197609232951305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu D.H., Lu Q., Xie J., Fang C., Chen H.Z. Peptide-conjugated biodegradable nanoparticles as a carrier to target paclitaxel to tumor neovasculature. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2278–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J., Li S., Shen Q. Folic acid and cell-penetrating peptide conjugated PLGA-PEG bifunctional nanoparticles for vincristine sulfate delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.: Official J. Eur. Federation Pharm. Sci. 2012;47(2):430–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aspland S.E., Ballatore C., Castillo R., Desharnais J., Eustaquio T., Goelet P., Guo Z., Li Q., Nelson D., Sun C., Castellino A.J., Newman M.J. Kinase-mediated trapping of bi-functional conjugates of paclitaxel or vinblastine with thymidine in cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16(19):5194–5198. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song W., Tang Z., Li M., Lv S., Sun H., Deng M., Liu H., Chen X. Polypeptide-based combination of paclitaxel and cisplatin for enhanced chemotherapy efficacy and reduced side-effects. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(3):1392–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C., Zhao M., Liu Y.R., Luan X., Guan Y.Y., Lu Q., Yu D.H., Bai F., Chen H.Z., Fang C. Suppression of colorectal cancer subcutaneous xenograft and experimental lung metastasis using nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery to tumor neovasculature. Biomaterials. 2014;35(4):1215–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien S., Schiller G., Lister J., Damon L., Goldberg S., Aulitzky W., Ben-Yehuda D., Stock W., Coutre S., Douer D., Heffner L.T., Larson M., Seiter K., Smith S., Assouline S., Kuriakose P., Maness L., Nagler A., Rowe J., Schaich M., Shpilberg O., Yee K., Schmieder G., Silverman J.A., Thomas D., Deitcher S.R., Kantarjian H. High-dose vincristine sulfate liposome injection for advanced, relapsed, and refractory adult Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol.: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31(6):676–683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kruczynski A., Hill B.T. Vinflunine, the latest Vinca alkaloid in clinical development. A review of its preclinical anticancer properties. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2001;40(2):159–173. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill B.T. Vinflunine, a second generation novel Vinca Alkaloid with a distinctive pharmacological profile, now in clinical development and prospects for future mitotic blockers. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2001;7(13):1199–1212. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braguer D., Barret J.M., McDaid H., Kruczynski A. Antitumor activity of vinflunine: effector pathways and potential for synergies. Semin. Oncol. 2008;35(3) Suppl. 3:S13–S21. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noble R.L. The discovery of the vinca alkaloids--chemotherapeutic agents against cancer. Biochem. Cell Biol. =. Biochimie et Biologie Cellulaire. 1990;68(12):1344–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng J.S. Vinflunine: review of a new vinca alkaloid and its potential role in oncology. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract.: Official Publication Int. Soc. Oncol. Pharm. Practitioners. 2011;17(3):209–224. doi: 10.1177/1078155210373525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schutz F.A., Bellmunt J., Rosenberg J.E., Choueiri T.K. Vinflunine: drug safety evaluation of this novel synthetic vinca alkaloid. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2011;10(4):645–653. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2011.581660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman J.A., Deitcher S.R. Marqibo® (vincristine sulfate liposome injection) improves the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of vincristine. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013;71(3):555–564. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison T.S., Lyseng-Williamson K.A. Vincristine sulfate liposome injection: a guide to its use in refractory or relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. BioDrugs. Clin. Immunother. Biopharm. Gene Therapy. 2013;27(1):69–74. doi: 10.1007/s40259-012-0002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis T., Farag S.S. Treating relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: liposome-encapsulated vincristine. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:3479–3488. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S47037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boehlke L., Winter J.N. Sphingomyelin/cholesterol liposomal vincristine: a new formulation for an old drug. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2006;6(4):409–415. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas D.A., Sarris A.H., Cortes J., Faderl S., O'Brien S., Giles F.J., Garcia-Manero G., Rodriguez M.A., Cabanillas F., Kantarjian H. Phase II study of sphingosomal vincristine in patients with recurrent or refractory adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;106(1):120–127. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang F., Wang H., Liu M., Hu P., Jiang J. Determination of free and total vincristine in human plasma after intravenous administration of vincristine sulfate liposome injection using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1275:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui J., Li C., Wang C., Li Y., Zhang L., Xiu X., Wei N. Development of pegylated liposomal vincristine using novel sulfobutyl ether cyclodextrin gradient: is improved drug retention sufficient to surpass DSPE-PEG-induced drug leakage? J. Pharm. Sci. 2011;100(7):2835–2848. doi: 10.1002/jps.22496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T., Zheng Y., Peng Q., Cao X., Gong T., Zhang Z. A novel submicron emulsion system loaded with vincristine-oleic acid ion-pair complex with improved anticancer effect: in vitro and in vivo studies. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:1185–1196. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S41775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aboutaleb E., Atyabi F., Khoshayand M.R., Vatanara A.R., Ostad S.N., Kobarfard F., Dinarvand R. Improved brain delivery of vincristine using dextran sulfate complex solid lipid nanoparticles: Optimization and in vivo evaluation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bedikian A.Y., Papadopoulos N.E., Kim K.B., Vardeleon A., Smith T., Lu B., Deitcher S.R. A pilot study with vincristine sulfate liposome infusion in patients with metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2008;18(6):400–404. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e328311aaa1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez M.A., Pytlik R., Kozak T., Chhanabhai M., Gascoyne R., Lu B., Deitcher S.R., Winter J.N. Vincristine sulfate liposomes injection (Marqibo) in heavily pretreated patients with refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma: report of the pivotal phase 2 study. Cancer. 2009;115(15):3475–3482. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong M.Y., Chiu G.N. Simultaneous liposomal delivery of quercetin and vincristine for enhanced estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer treatment. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21(4):401–410. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328336e940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pathak P., Hess R., Weiss M.A. Liposomal vincristine for relapsed or refractory Ph-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a review of literature. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2014;5(1):18–24. doi: 10.1177/2040620713519016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato J., Li Y., Xiao K., Lee J.S., Luo J., Tuscano J.M., O'Donnell R.T., Lam K.S. Disulfide cross-linked micelles for the targeted delivery of vincristine to B-cell lymphoma. Mol. Pharm. 2012;9(6):1727–1735. doi: 10.1021/mp300128b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaplan L.D., Deitcher S.R., Silverman J.A., Morgan G. Phase II study of vincristine sulfate liposome injection (Marqibo) and rituximab for patients with relapsed and refractory diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma in need of palliative therapy. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xi G., Rajaram V., Mania-Farnell B., Mayanil C.S., Soares M.B., Tomita T., Goldman S. Efficacy of vincristine administered via convection-enhanced delivery in a rodent brainstem tumor model documented by bioluminescence imaging. Child's Nerv. Syst.: ChNS: Official J. Int. Soc. Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2012;28(4):565–574. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1690-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozeki T., Kaneko D., Hashizawa K., Imai Y., Tagami T., Okada H. Improvement of survival in C6 rat glioma model by a sustained drug release from localized PLGA microspheres in a thermoreversible hydrogel. Int. J. Pharm. 2012;427(2):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hagemeister F., Rodriguez M.A., Deitcher S.R., Younes A., Fayad L., Goy A., Dang N.H., Forman A., McLaughlin P., Medeiros L.J., Pro B., Romaguera J., Samaniego F., Silverman J.A., Sarris A., Cabanillas F. Long term results of a phase 2 study of vincristine sulfate liposome injection (Marqibo(®)) substituted for non-liposomal vincristine in cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone with or without rituximab for patients with untreated aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Br. J. Haematol. 2013;162(5):631–638. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Y., Xu L., Zhang Q., Zhou H. The controlled release study of Vincristine Sulfate. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 2003;31(1):81–88. doi: 10.1081/bio-120018005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang C.H., Huang K.S., Grumezescu A.M., Wang C.Y., Tzeng S.C., Chen S.Y., Lin Y.H., Lin Y.S. Synthesis of uniform poly(d,l-lactide) and poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres using a microfluidic chip for comparison. Electrophoresis. 2013 doi: 10.1002/elps.201300185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin Y.S., Yang C.H., Wu C.T., Grumezescu A.M., Wang C.Y., Hsieh W.C., Chen S.Y., Huang K.S. A microfluidic chip using phenol formaldehyde resin for uniform-sized polycaprolactone and chitosan microparticles generation. Molecules. 2013;18:6521–6531. doi: 10.3390/molecules18066521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin Y.S., Yang C.H., Wang C.Y., Chang F.R., Huang K.S., Hsieh W.C. An Aluminum Microfluidic Chip Fabrication Using a Convenient Micromilling Process for Fluorescent Poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) Microparticles Generation. Sensors-BASEL. 2012;12:1455–1467. doi: 10.3390/s120201455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang C.H., Huang K.S., Lin Y.S., Lu K., Tzeng C.C., Wang E.C., Lin C.H., Hsu W.Y., Chang J.Y. Microfluidic assisted synthesis of multi-functional polycaprolactone microcapsules: incorporation of CdTe quantum dots, Fe3O4 superparamagnetic nanoparticles and tamoxifen anticancer drugs. Lab Chip. 2009;9(7):961–965. doi: 10.1039/b814952f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ling G., Zhang P., Zhang W., Sun J., Meng X., Qin Y., Deng Y., He Z. Development of novel self-assembled DS-PLGA hybrid nanoparticles for improving oral bioavailability of vincristine sulfate by P-gp inhibition. J. Control. Release: Official J. Control. Release Soc. 2010;148(2):241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang P., Ling G., Sun J., Zhang T., Yuan Y., Sun Y., Wang Z., He Z. Multifunctional nanoassemblies for vincristine sulfate delivery to overcome multidrug resistance by escaping P-glycoprotein mediated efflux. Biomaterials. 2011;32(23):5524–5533. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Urbinati G., Marsaud V., Renoir J.M. Anticancer drugs in liposomal nanodevices: a target delivery for a targeted therapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012;12(15):1693–1712. doi: 10.2174/156802612803531423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Samad A., Sultana Y., Aqil M. Liposomal drug delivery systems: an update review. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2007;4(4):297–305. doi: 10.2174/156720107782151269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu D., Zhang N. Cancer chemotherapy with lipid-based nanocarriers. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2010;27(5):371–417. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v27.i5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slingerland M., Guchelaar H.J., Gelderblom H. Liposomal drug formulations in cancer therapy: 15 years along the road. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17(3-4):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Livney Y.D., Assaraf Y.G. Rationally designed nanovehicles to overcome cancer chemoresistance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013;65(13-14):1716–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y., Dou L., He H., Zhang Y., Shen Q. Multifunctional Nanoparticles as Nanocarrier for Vincristine Sulfate Delivery To Overcome Tumor Multidrug Resistance. Mol. Pharm. 2014 doi: 10.1021/mp400547u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen H., Liu L., Yuan P., Zhang Q. The study of improved controlled release of vincristine sulfate from collagen-chitosan complex film. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 2008;36(4):372–385. doi: 10.1080/10731190802239057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Junping W., Takayama K., Nagai T., Maitani Y. Pharmacokinetics and antitumor effects of vincristine carried by microemulsions composed of PEG-lipid, oleic acid, vitamin E and cholesterol. Int. J. Pharm. 2003;251(1-2):13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00580-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong M.Y., Chiu G.N. Liposome formulation of co-encapsulated vincristine and quercetin enhanced antitumor activity in a trastuzumab-insensitive breast tumor xenograft model. Nanomedicine. 2011;7(6):834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zucker D., Andriyanov A.V., Steiner A., Raviv U., Barenholz Y. Characterization of PEGylated nanoliposomes co-remotely loaded with topotecan and vincristine: relating structure and pharmacokinetics to therapeutic efficacy. J. Control. Release: Official J. Control. Release Soc. 2012;160(2):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thakkar H.P., Baser A.K., Parmar M.P., Patel K.H., Ramachandra Murthy R. Vincristine-sulphate-loaded liposome-templated calcium phosphate nanoshell as potential tumor-targeting delivery system. J. Liposome Res. 2012;22(2):139–147. doi: 10.3109/08982104.2011.633266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vincristine liposomal--INEX: lipid-encapsulated vincristine, onco TCS, transmembrane carrier system--vincristine, vincacine, vincristine sulfate liposomes for injection, VSLI. Drugs R D. 2004;5(2):119–123. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200405020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhong J., Mao W., Shi R., Jiang P., Wang Q., Zhu R., Wang T., Ma Y. Pharmacokinetics of liposomal-encapsulated and un-encapsulated vincristine after injection of liposomal vincristine sulfate in beagle dogs. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014;73(3):459–466. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verreault M., Strutt D., Masin D., Anantha M., Yung A., Kozlowski P., Waterhouse D., Bally M.B., Yapp D.T. Vascular normalization in orthotopic glioblastoma following intravenous treatment with lipid-based nanoparticulate formulations of irinotecan (Irinophore C), doxorubicin (Caelyx®) or vincristine. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tan R., Niu M., Zhao J., Liu Y., Feng N. Preparation of vincristine sulfate-loaded poly (butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles modified with pluronic F127 and evaluation of their lymphatic tissue targeting. J. Drug Target. 2014 doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2014.897708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu Y., Hou S.X., Zhang L.K., Li Y., He J.Y., Guo D.D. [Transdermal and lymph targeting transfersomes of vincristine]. Yao xue xue bao = Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. 2007;42(10):1097–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parthasarathi G., Udupa N., Parameshwaraiah N., Pillai G.K. Altered biological distribution and decreased neuromuscular toxicity of niosome encapsulated vincristine. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 1996;34(2):124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parthasarathi G., Udupa N., Umadevi P., Pillai G.K. Niosome encapsulated of vincristine sulfate: improved anticancer activity with reduced toxicity in mice. J. Drug Target. 1994;2(2):173–182. doi: 10.3109/10611869409015907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maswadeh H., Demetzos C., Daliani I., Kyrikou I., Mavromoustakos T., Tsortos A., Nounesis G. A molecular basis explanation of the dynamic and thermal effects of vinblastine sulfate upon dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1567(1-2):49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kyrikou I., Daliani I., Mavromoustakos T., Maswadeh H., Demetzos C., Hatziantoniou S., Giatrellis S., Nounesis G. The modulation of thermal properties of vinblastine by cholesterol in membrane bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1661(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dandamudi S., Campbell R.B. The drug loading, cytotoxicty and tumor vascular targeting characteristics of magnetite in magnetic drug targeting. Biomaterials. 2007;28(31):4673–4683. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vacca A., Iurlaro M., Ribatti D., Minischetti M., Nico B., Ria R., Pellegrino A., Dammacco F. Antiangiogenesis is produced by nontoxic doses of vinblastine. Blood. 1999;94(12):4143–4155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Faneca H., Faustino A., Pedroso de Lima M.C. Synergistic antitumoral effect of vinblastine and HSV-Tk/GCV gene therapy mediated by albumin-associated cationic liposomes. J. Control. Release: Official J. Control. Release Soc. 2008;126(2):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vlahov I.R., Santhapuram H.K., Kleindl P.J., Howard S.J., Stanford K.M., Leamon C.P. Design and regioselective synthesis of a new generation of targeted chemotherapeutics. Part 1: EC145, a folic acid conjugate of desacetylvinblastine monohydrazide. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16(19):5093–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dandamudi S., Patil V., Fowle W., Khaw B.A., Campbell R.B. External magnet improves antitumor effect of vinblastine and the suppression of metastasis. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(8):1537–1543. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li J., Sausville E.A., Klein P.J., Morgenstern D., Leamon C.P., Messmann R.A., LoRusso P. Clinical pharmacokinetics and exposure-toxicity relationship of a folate-Vinca alkaloid conjugate EC145 in cancer patients. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009;49(12):1467–1476. doi: 10.1177/0091270009339740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yanagawa A., Mizushima Y., Komatsu A., Horiuchi M., Shirasawa E., Igarashi R. Application of a drug delivery system to a steroidal ophthalmic preparation with lipid microspheres. J. Microencapsul. 1987;4(4):329–331. doi: 10.3109/02652048709021825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vlahov I.R., Santhapuram H.K., You F., Wang Y., Kleindl P.J., Hahn S.J., Vaughn J.F., Reno D.S., Leamon C.P. Carbohydrate-based synthetic approach to control toxicity profiles of folate-drug conjugates. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75(11):3685–3691. doi: 10.1021/jo100448q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dhawan D., Ramos-Vara J.A., Naughton J.F., Cheng L., Low P.S., Rothenbuhler R., Leamon C.P., Parker N., Klein P.J., Vlahov I.R., Reddy J.A., Koch M., Murphy L., Fourez L.M., Stewart J.C., Knapp D.W. Targeting folate receptors to treat invasive urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(2):875–884. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zu Y., Zhang Y., Zhao X., Zhang Q., Liu Y., Jiang R. Optimization of the preparation process of vinblastine sulfate (VBLS)-loaded folate-conjugated bovine serum albumin (BSA) nanoparticles for tumor-targeted drug delivery using response surface methodology (RSM). Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2009;4:321–333. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s8501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marinina J., Shenderova A., Mallery S.R., Schwendeman S.P. Stabilization of vinca alkaloids encapsulated in poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. Pharm. Res. 2000;17(6):677–683. doi: 10.1023/a:1007522013835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Noble C.O., Guo Z., Hayes M.E., Marks J.D., Park J.W., Benz C.C., Kirpotin D.B., Drummond D.C. Characterization of highly stable liposomal and immunoliposomal formulations of vincristine and vinblastine. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2009;64(4):741–751. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0923-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maswadeh H., Demetzos C., Dimas K., Loukas Y.L., Georgopoulos A., Mavromoustakos T., Papaioannou G.T. In-vitro cytotoxic/cytostatic activity of anionic liposomes containing vinblastine against leukaemic human cell lines. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2002;54(2):189–196. doi: 10.1211/0022357021778376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maswadeh H., Hatziantoniou S., Demetzos C., Dimas K., Georgopoulos A., Rallis M. Encapsulation of vinblastine into new liposome formulations prepared from triticum (wheat germ) lipids and its activity against human leukemic cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(6B):4385–4390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Seid C.A., Fidler I.J., Clyne R.K., Earnest L.E., Fan D. Overcoming murine tumor cell resistance to vinblastine by presentation of the drug in multilamellar liposomes consisting of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine. Sel. Cancer Ther. 1991;7(3):103–112. doi: 10.1089/sct.1991.7.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang H.Y., Tang X., Li H.Y., Liu X.L. A lipid microsphere vehicle for vinorelbine: Stability, safety and pharmacokinetics. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;348(1-2):70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Su M., Zhao M., Luo Y., Lin X., Xu L., He H., Xu H., Tang X. Evaluation of the efficacy, toxicity and safety of vinorelbine incorporated in a lipid emulsion. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;411(1-2):188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Y., Jin W., Yan H., Liu H., Wang C. Development of intravenous lipid emulsion of vinorelbine based on drug-phospholipid complex technique. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;454(1):472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Drummond D.C., Noble C.O., Guo Z., Hayes M.E., Park J.W., Ou C.J., Tseng Y.L., Hong K., Kirpotin D.B. Improved pharmacokinetics and efficacy of a highly stable nanoliposomal vinorelbine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;328(1):321–330. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.141200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee W.C., Chang C.H., Huang C.M., Wu Y.T., Chen L.C., Ho C.L., Chang T.J., Lee T.W., Tsai T.H. Correlation between radioactivity and chemotherapeutics of the (111)In-VNB-liposome in pharmacokinetics and biodistribution in rats. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2012;7:683–692. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S28279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takenaga M. Application of lipid microspheres for the treatment of cancer. Lipid Microspheres. 1996;20(2-3):209–219. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu L., Pan J., Chen Q., Yu Q., Chen H., Xu H., Qiu Y., Yang X. In vivo evaluation of the safety of triptolide-loaded hydrogel-thickened microemulsion. Food Chem. Toxicol. An International Journal Published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association. 2008;46(12):3792–3799. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang H., Wang Z.Y., Gong W., Li Z.P., Mei X.G., Lv W.L. Development and characteristics of temperature-sensitive liposomes for vinorelbine bitartrate. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;414(1-2):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bae Y.H., Yin H. Stability issues of polymeric micelles. J. Control. Release: Official J. Control. Release Soc. 2008;131(1):2–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tang N., Du G., Wang N., Liu C., Hang H., Liang W. Improving penetration in tumors with nanoassemblies of phospholipids and doxorubicin. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99(13):1004–1015. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Qin L., Zhang F., Lu X., Wei X., Wang J., Fang X., Si D., Wang Y., Zhang C., Yang R., Liu C., Liang W. Polymeric micelles for enhanced lymphatic drug delivery to treat metastatic tumors. J. Control. Release: Official J. Control. Release Soc. 2013;171(2):133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lin Y.Y., Li J.J., Chang C.H., Lu Y.C., Hwang J.J., Tseng Y.L., Lin W.J., Ting G., Wang H.E. Evaluation of pharmacokinetics of 111In-labeled VNB-PEGylated liposomes after intraperitoneal and intravenous administration in a tumor/ascites mouse model. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2009;24(4):453–460. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2008.0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li C., Cui J., Wang C.L., Xiu X., Li Y., Wei N., Li Y., Zhang L. Encapsulation of vinorelbine into cholesterol-polyethylene glycol coated vesicles: drug loading and pharmacokinetic studies. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011;63(3) doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roth A., Drummond D.C., Conrad F., Hayes M.E., Kirpotin D.B., Benz C.C., Marks J.D., Liu B. Anti-CD166 single chain antibody-mediated intracellular delivery of liposomal drugs to prostate cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007;6(10):2737–2746. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhou W., Zhou Y., Wu J., Liu Z., Zhao H., Liu J., Ding J. Aptamer-nanoparticle bioconjugates enhance intracellular delivery of vinorelbine to breast cancer cells. J. Drug Target. 2014;22(1):57–66. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2013.839683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wan F., You J., Sun Y., Zhang X.G., Cui F.D., Du Y.Z., Yuan H., Hu F.Q. Studies on PEG-modified SLNs loading vinorelbine bitartrate (I): preparation and evaluation in vitro. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;359(1-2):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lu X., Zhang F., Qin L., Xiao F., Liang W. Polymeric micelles as a drug delivery system enhance cytotoxicity of vinorelbine through more intercellular. Drug Deliv. 2010;17(4):255–262. doi: 10.3109/10717541003702769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.You J., Wan F., de Cui F., Sun Y., Du Y.Z., Hu F.Q. Preparation and characteristic of vinorelbine bitartrate-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2007;343(1-2):270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rhomberg W., Wink A., Pokrajac B., Eiter H., Hackl A., Pakisch B., Ginestet A., Lukas P., Potter R. Treatment of vascular soft tissue sarcomas with razoxane, vindesine, and radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009;74(1):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jordan M.A., Himes R.H., Wilson L. Comparison of the effects of vinblastine, vincristine, vindesine, and vinepidine on microtubule dynamics and cell proliferation in vitro. Cancer Res. 1985;45(6):2741–2747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Joel S. The comparative clinical pharmacology of vincristine and vindesine: does vindesine offer any advantage in clinical use? Cancer Treat. Rev. 1996;21(6):513–525. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(95)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Simoens C. New vinca alkaloids in cancer treatment. http://www.hospitalpharmacyeurope.com/featured-articles/newvinca- alkaloids-cancer-treatment . 2006.

- 111.DiJoseph J.F., Dougher M.M., Evans D.Y., Zhou B.B., Damle N.K. Preclinical anti-tumor activity of antibody-targeted chemotherapy with CMC-544 (inotuzumab ozogamicin), a CD22-specific immunoconjugate of calicheamicin, compared with non-targeted combination chemotherapy with CVP or CHOP. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011;67(4):741–749. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1342-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lugtenburg P., Silvestre A.S., Rossi F.G., Noens L., Krall W., Bendall K., Szabo Z., Jaeger U. Impact of age group on febrile neutropenia risk assessment and management in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP regimens. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012;12(5):297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Michallet A.S., Coiffier B. Recent developments in the treatment of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Rev. 2009;23(1):11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pettengell R., Johnsen H.E., Lugtenburg P.J., Silvestre A.S., Duhrsen U., Rossi F.G., Schwenkglenks M., Bendall K., Szabo Z., Jaeger U. Impact of febrile neutropenia on R-CHOP chemotherapy delivery and hospitalizations among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Support. Care Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20(3):647–652. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1306-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Waters E., Dingle B., Rodrigues G., Vincent M., Ash R., Dar R., Inculet R., Kocha W., Malthaner R., Sanatani M., Stitt L., Yaremko B., Younus J., Yu E. Analysis of a novel protocol of combined induction chemotherapy and concurrent chemoradiation in unresected non-small-cell lung cancer: a ten-year experience with vinblastine, Cisplatin, and radiation therapy. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2010;11(4):243–250. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2010.n.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fizazi K., Do K.A., Wang X., Finn L., Logothetis C.J., Amato R.J., Logothetis C.J., Amato R.J. A 20% dose reduction of the original CISCA/VB regimen allows better tolerance and similar survival rate in disseminated testicular non-seminomatous germ-cell tumors: final results of a phase III randomized trial. Ann. Oncol.: Official J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. ESMO. 2002;13:125–134. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schwenkglenks P.R., Szucs T.D., Culakova E., Lyman G.H. Hodgkin lymphoma treatment with ABVD in the US and the EU: neutropenia occurrence and impaired chemotherapy delivery. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2010;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ramsey S.D., Moinpour C.M., Lovato L.C., Crowley J.J., Grevstad P., Presant C.A., Rivkin S.E., Kelly K., Gandara D.R. Economic analysis of vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002;94(4):291–297. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pepe C., Hasan B., Winton T.L., Seymour L., Graham B., Livingston R.B., Johnson D.H., Rigas J.R., Ding K., Shepherd F.A. Adjuvant vinorelbine and cisplatin in elderly patients: National Cancer Institute of Canada and Intergroup Study JBR.10. J. Clin. Oncol.: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(12):1553–1561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kreuter M., Vansteenkiste J., Griesinger F., Hoffmann H., Dienemann H., De Leyn P., Thomas M. Trial on refinement of early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Adjuvant chemotherapy with pemetrexed and cisplatin versus vinorelbine and cisplatin: the TREAT protocol. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Reinmuth N., Meyer A., Hartwigsen D., Schaeper C., Huebner G., Skock-Lober R., Bier A., Gerecke U., Held C.P., Reck M. Randomized, double-blind phase II study to compare nitroglycerin plus oral vinorelbine plus cisplatin with oral vinorelbine plus cisplatin alone in patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer. 2014;83(3):363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Imamura F., Konishi K., Uchida J., Nishino K., Okuyama T., Kumagai T., Kawaguchi Y., Nishiyama K. Novel chemoradiation with concomitant boost thoracic radiation and concurrent cisplatin and vinorelbine for stage III A and III B non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2014;15(4):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]