Abstract

Background

The effectiveness of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) for primary prevention of sudden death in patients with an ejection fraction (EF) ≤35% and clinical heart failure is well established. However, outcomes after replacement of the ICD generator in patients with recovery of EF to >35% and no previous therapies are not well characterized.

Methods and Results

Between 2001 and 2011, generator replacement was performed at 2 tertiary medical centers in 253 patients (mean age, 68.3±12.7 years; 82% men) who had previously undergone ICD placement for primary prevention but subsequently never received appropriate ICD therapy. EF had recovered to >35% in 72 of 253 (28%) patients at generator replacement. During median (quartiles) follow-up of 3.3 (1.8–5.3) years after generator replacement, 68 of 253 (27%) experienced appropriate ICD therapy. Patients with EF ≤35% were more likely to experience ICD therapy compared with those with EF >35% (12% versus 5% per year; hazard ratio, 3.57; P=0.001). On multivariable analysis, low EF predicted appropriate ICD therapy after generator replacement (hazard ratio, 1.96 [1.35–2.87] per 10% decrement; P=0.001). Death occurred in 25% of patients 5 years after generator replacement. Mortality was similar in patients with EF ≤35% and >35% (7% versus 5% per year; hazard ratio, 1.10; P=0.68). Atrial fibrillation (3.24 [1.63–6.43]; P<0.001) and higher blood urea nitrogen (1.28 [1.14–1.45] per increase of 10 mg/dL; P<0.001) were associated with mortality.

Conclusions

Although approximately one fourth of patients with a primary prevention ICD and no previous therapy have EF >35% at the time of generator replacement, these patients continue to be at significant risk for appropriate ICD therapy (5% per year). These data may inform decisions on ICD replacement.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy; death, sudden; defibrillators, implantable; follow-up studies; left ventricular ejection fraction; primary prevention; shock

The role of the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) for primary prevention of sudden death in patients with low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) caused by coronary or noncoronary heart disease is well established.1–3 Current guidelines and appropriate use criteria for initial primary prevention ICD implantation are heavily weighted by LVEF and New York Heart Association functional class.4,5 However, 40% of ICD-related procedures in the United States involve replacement of ICD generators because of battery depletion in pre-existing systems.6 There are a paucity of data on the ongoing risk and outcomes of patients undergoing generator replacement.

LVEF at the time of ICD generator replacement is, on average, 4% to 5% higher than at the time of initial implant,6 and patients may have improvement in their LVEF to >35%, the cutoff used to risk stratify the majority of patients at time of initial implant. Furthermore, 75% to 80% of primary prevention ICD recipients remain free of appropriate ICD therapy during the lifetime of their first ICD generator.6,7 The benefit of extending ICD coverage for primary prevention in recipients who have never received an appropriate therapy after years of follow-up and who no longer meet the LVEF criterion is unclear.8

Patients presenting for ICD generator replacement are older and have more cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities than recipients of an initial ICD implant, significantly affecting the potential benefits of ICD replacement.6,9 ICD replacement is associated with significant healthcare expenditure and greater risk of complications, such as infection and lead damage compared with initial implant.10,11 Therefore, the time of ICD generator replacement affords a unique opportunity to evaluate the risks and benefits of ongoing ICD therapy, and better characterization of outcome after ICD replacement is essential to informed decision making. We hypothesized that the incidence of appropriate therapy after ICD generator replacement would be low in patients with recovery of LVEF to >35% and no history of appropriate ICD therapy at the time of replacement. To test this hypothesis, we retrospectively analyzed the prospectively collected databases from 2 tertiary referral centers in the United States.

Methods

Study Population

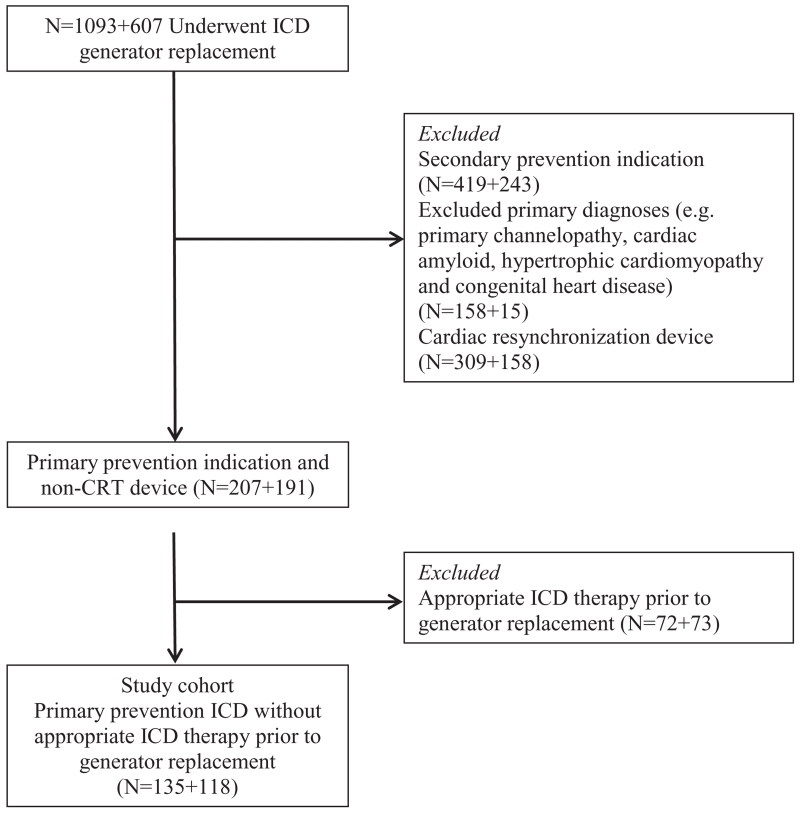

Data from all patients undergoing their first ICD generator replacement between January 2001 and June 2011 at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, or at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, were reviewed for the following inclusion criteria: (1) initial ICD implantation for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death and (2) the absence of appropriate ICD therapy for ventricular arrhythmia during the life span of the first pulse generator. Patients with an ICD implanted for sustained ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation inducible with programmed stimulation and without a history of syncope or spontaneous sustained ventricular arrhythmias were included. Exclusion criteria included patients with a cardiac resynchronization therapy device at initial implantation or upgrade to a cardiac resynchronization therapy at the time of generator change, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, cardiac amyloidosis, other infiltrative cardiomyopathy, primary channelopathy, or congenital heart disease. The flowchart of patients in the study is presented in Figure 1. Details of ICD-related procedures and follow-up were maintained in a prospective ICD registry at both institutions. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at both institutions.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients in this study. CRT indicates cardiac resynchronization therapy; and ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Variables

Demographic characteristics, cardiac and noncardiac medical comorbidities, medication use, and laboratory measures, including hemoglobin, creatinine, and sodium levels, were obtained from the medical records at the time of generator replacement. LVEF obtained within 6 months before or 3 months after ICD generator replacement using echocardiography or radionuclide angiography was obtained from the review of medical records. An ongoing indication for ICD therapy was defined as LVEF ≤35%. Patients for whom the LVEF was not available at the time of generator replacement (5/253) were classified as having an ongoing indication for an ICD. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.12

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were the first appropriate ICD therapy after first generator replacement and mortality. Appropriate ICD therapy was defined as antitachycardia pacing or shock delivery for ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Appropriateness of ICD therapies was adjudicated by an electrophysiologist or specially trained electrophysiology nurse based on the review of stored electrograms. Follow-up for the end point of appropriate ICD therapy was censored if a patient transferred care of the ICD to a different institution. Data on mortality were obtained from the National Death Index. Follow-up for the mortality end point was terminated on the date these data were obtained.

Statistical Methods

Categorical variables are summarized as number (%) and compared using the χ2 test. Continuous variables are summarized using mean±SD or median (quartiles) and compared using the t test or the rank-sum test as appropriate. The risk of overall mortality and appropriate ICD therapy were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate both unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs). Covariates for adjustment were selected based on risk factors with P<0.1 in the unadjusted analysis, and stepwise selection was used to construct the multivariable models. A 2-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed independently by the authors using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Study Population and Procedure Characteristics

Two hundred and fifty-three primary prevention ICD recipients without appropriate therapy for the life span of their first device who underwent first generator replacement were included in this analysis. The clinical characteristics of the entire cohort stratified by the presence or the absence of LVEF recovery to >35% are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 68.3 (±12.7) years, 207 (82%) patients were men, and 194 (82%) had coronary artery disease as the cause of their systolic dysfunction. The mean interval between initial ICD implantation and generator replacement was 4.8 (±1.9) years. The generator was replaced because of battery depletion in the majority of patients (70%) with device advisory/malfunction (23.3%), upgrade (4%), and infection (2.4%) constituting the remaining indications for ICD generator replacement. Generator longevity was 5.5 (±1.6) years in patients with battery depletion. Forty-one (16%) patients also underwent revision of ≥1 leads at the time of generator replacement.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Who Underwent ICD Generator Change Stratified by EF.

| Clinical Characteristics* | Overall Cohort (n=253) |

EF≤35% (n=181) |

EF>35% (n=72) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 68.3 (12.7) | 68.2 (12.8) | 68.4 (12.6) | 0.77 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 207 (81.8) | 154 (85.1) | 53 (73.6) | 0.033 |

| White race | 231 (91.3) | 166 (91.7) | 65 (90.3) | 0.08 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.7 (5.7) | 28.3 (5.5) | 29.5 (6.2) | 0.23 |

| Underlying cardiomyopathy, n (%) | ||||

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 194 (81.9) | 141 (83.4) | 55 (80.9) | 0.61 |

| Nonischemic cardiomyopathy | 41 (17.3) | 28 (16.6) | 13 (19.1) | |

| Reason for ICD generator change, n (%) | ||||

| Elective replacement indicator | 177 (70.0) | 124 (68.5) | 53 (73.6) | 0.67 |

| Device advisory or malfunction | 59 (23.3) | 43 (23.8) | 16 (22.2) | |

| Device upgrade | 10 (4.0) | 9 (5.0) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Infection | 6 (2.4) | 4 (2.2) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Lead revision at the time of ICD generator replacement, n (%) | 41 (16.2) | 33 (18.2) | 8 (11.1) | 0.17 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, n (%) | 32.3 (12.4) | 26.0 (6.4) | 47.7 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| NYHA class, n (%) | ||||

| Class I | 100 (50.3) | 65 (45.1) | 35 (63.6) | 0.043 |

| Class II | 70 (35.2) | 54 (37.5) | 16 (29.1) | |

| Class III | 29 (14.6) | 25 (17.4) | 4 (7.3) | |

| Rhythm, n (%) | ||||

| Sinus rhythm with intrinsic conduction | 134 (60.9) | 95 (62.1) | 39 (58.2) | 0.94 |

| Atrial fibrillation with intrinsic conduction | 12 (5.5) | 8 (5.2) | 4 (6.0) | |

| Ventricular paced rhythm | 60 (27.3) | 40 (26.1) | 20 (29.9) | |

| QRS duration, ms (median, interquartile range) | 118 (100–158) | 122 (104–156) | 113 (94–162) | 0.29 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||

| ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker | 197 (84.5) | 148 (89.2) | 49 (73.1) | 0.002 |

| β-Blocker | 217 (93.1) | 158 (95.2) | 59 (88.1) | 0.05 |

| Cardiovascular history, n (%) | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 179 (70.8) | 128 (70.7) | 51 (70.8) | 0.99 |

| Coronary artery disease | 203 (80.2) | 150 (82.9) | 53 (73.6) | 0.10 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 115 (45.5) | 81 (44.8) | 34 (47.2) | 0.72 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 40 (15.8) | 35 (19.3) | 5 (6.9) | 0.015 |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 40 (15.8) | 32 (17.7) | 8 (11.1) | 0.20 |

| Medical comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 192 (75.9) | 134 (74.0) | 58 (80.6) | 0.27 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 88 (34.8) | 65 (35.9) | 23 (31.9) | 0.55 |

| Chronic lung disease | 33 (13.0) | 17 (9.4) | 16 (22.2) | 0.006 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.9 (1.9) | 12.8 (2.0) | 13.1 (1.8) | 0.35 |

| Serum sodium, mEq/L | 139.4 (3.1) | 139.3 (3.2) | 139.6 (3.1) | 0.57 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.3 (0.7) | 0.040 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 27.9 (18.1) | 29.2 (19.7) | 25.0 (13.8) | 0.17 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 65.3 (27.4) | 63.8 (27.1) | 69.2 (28.0) | 0.18 |

| Programmed zone (median and minimum–maximum), beats per min | ||||

| VF zone | 188 (170–316) | 188 (170–316) | 200 (185–220) | … |

| VTzone | 164 (150–194) (n=72) | 160 (150–194) (n=54) | 170 (140–182) (n=18) | … |

ACE indicates angiotensin-converting enzyme; EF, ejection fraction; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; NYHA, New York Heart Association; VF, ventricular fibrillation; and VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Data are presented as mean (SD) or n (%) except when indicated otherwise.

EF and Guideline-Based Indication for ICD at Generator Replacement

Mean LVEF before generator replacement in the overall cohort was 32.3±12.4%. LVEF was >35% in 72 of 253 (28%) patients (Table 1). The mean LVEF in the group with EF >35% was 47.7±9.6% compared with 26.0±6.4% in the group with LVEF ≤35% (P<0.001). Patients with improvement in LVEF to >35% were more likely to be women and were less likely to have New York Heart Association functional class II or III symptoms. Lower observed rates of therapy with β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and aldosterone receptor blockers in the group with EF>35% may be attributed to a higher rate of discontinuation of these medications after LVEF improvement. Patients with EF ≤35% were also more likely to have a history of peripheral vascular disease (19.3% versus 6.9%; P=0.015) and higher serum creatinine levels (1.5±1.1 versus 1.3±0.7 mg/dL; P=0.040). LVEF was >45% in 13% and >50% in 8% of the cohort.

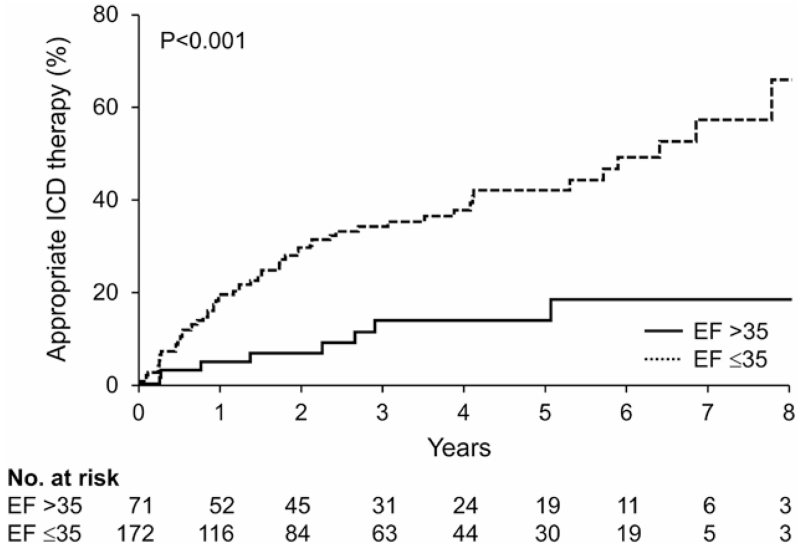

Rates of Appropriate ICD Therapy After Generator Replacement

The first appropriate ICD therapy occurred after generator replacement in 68 of 253 patients during a median (quartiles) follow-up of 3.3 (1.8–5.3) years, with a rate of 7% per year. The Kaplan–Meier estimated cumulative incidence of first appropriate therapy at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years was 15%, 23%, 28%, and 36%, respectively. Patients with EF≤35% were more likely to experience an appropriate therapy than patients without (12% versus 5% per year; HR, 3.57; P=0.001). When stratified by LVEF, the 1-, 2-, and 3-year cumulative rates of appropriate ICD therapy for a ventricular arrhythmia increased over time in the group with EF ≤35% (20%, 30%, and 35%, respectively) with a smaller increase in those with EF >35% (7%, 9%, and 14%, respectively). Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier analysis of first appropriate therapy stratified by EF is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier analysis of appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy after generator replacement stratified by the presence or the absence of continuing indication for ICD therapy. EF indicates ejection fraction.

ICD programming can affect the rate of appropriate therapy significantly and is summarized here. All patients had a programmed ventricular fibrillation zone at median (minimum–maximum) of 188 (170–316) beats per minute. Detection parameters in this zone were programmed as 12/16 intervals (n=36), 18/24 intervals (n=125), 24/32 intervals (n=3), 30/40 intervals (n=21), or 1 (1–2.5) s (median, minimum–maximum). A second lower zone was programmed in 72 (28%) patients at median (minimum–maximum) of 164 (150–194) beats per minute. Detection parameters in this zone were either median (minimum–maximum) of 16 (16–32) intervals or 2.5 (1.0–12.0) s. ICD programming in the groups stratified by LVEF is summarized in Table 1.

Because the duration from first ICD implantation to generator replacement was variable, the rate of postgenerator replacement ICD therapy was examined in each quartile of time from initial implantation to replacement. There was no statistically significant difference in the probability of receiving ICD therapy after generator replacement as a function of how soon a patient received a generator change after initial implant (36%, 26%, 23%, and 22% in each quartile; P=0.30).

Significant predictors of first appropriate therapy in univariate analysis included lower LVEF, higher New York Heart Association functional class, lower hemoglobin, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate, and higher blood urea nitrogen (Table 2). A trend toward statistical significance was noted for history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, QRS duration, and serum sodium. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model of risk factors for the first appropriate ICD therapy after ICD generator replacement is presented in Table 3. After multivariable adjustment, lower LVEF (1.96 [1.35–2.87] per 10% decrease; P=0.001), lower hemoglobin (1.21 [1.03–1.42] per decrement of 1 g/dL; P=0.021), and lower serum sodium (HR, 4.31 [1.41–13.16] per decrement of 10 mEq/L; P=0.010) were independently associated with the first appropriate ICD therapy.

Table 2. Univariate Predictors of the First Appropriate Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Therapy After Generator Replacement.

| Risk Factor | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (per 10% decrement) |

1.48 | 1.16–1.89 | 0.002 |

| NYHA functional class (per increase in NYHA class of 1) |

1.72 | 1.18–2.45 | 0.005 |

| QRS duration (per increment of 10 ms) | 1.06 | 0.99–1.12 | 0.08 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 1.78 | 0.99–3.21 | 0.055 |

| Hemoglobin (per decrement of 1 g/dL) | 1.18 | 1.04–1.35 | 0.011 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (per decrement of 10 mL/min 1.73 m2) |

1.12 | 1.02–1.23 | 0.02 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (per increment of 10 mg/dL) |

1.14 | 1.03–1.26 | 0.010 |

| Serum sodium (per decrement of 10 mEq/L) |

2.18 | 0.97–4.90 | 0.060 |

CI indicates confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; and NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Table 3. Predictors of First Appropriate Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Therapy After Generator Replacement in Multivariable Analysis.

| Risk Factor | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (per decrement of 10%) |

1.96 | 1.35–2.87 | 0.001 |

| Serum sodium (per decrement of 10 mEq/L) |

4.31 | 1.41–13.16 | 0.010 |

| Hemoglobin (per decrement of 1 g/dL) | 1.21 | 1.03–1.42 | 0.021 |

CI indicates confidence interval; and HR, hazard ratio.

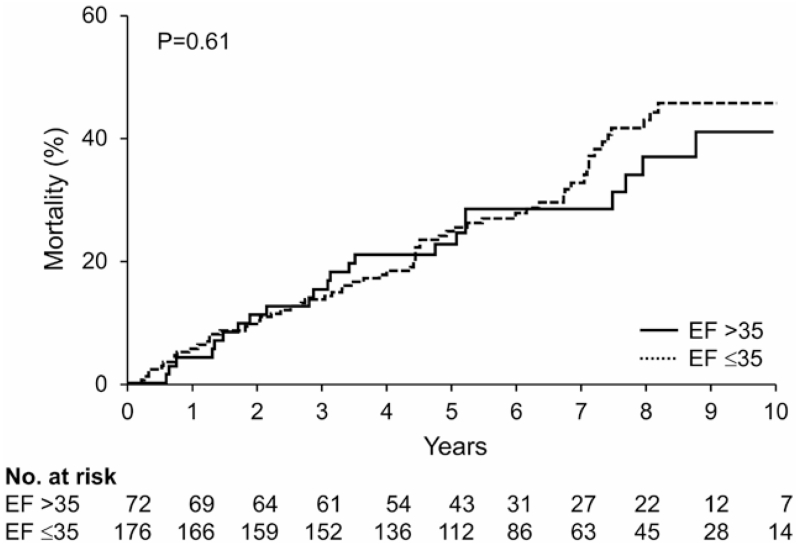

Mortality After Generator Replacement

Death occurred in 90 patients over a median (quartile) follow-up of 5.8 (4.2–8.1) years with a mortality rate of 5% per year. The Kaplan–Meier estimated the mortality rate at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years was 5%, 10%, 14%, and 25%, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in mortality between patients with EF ≤35% and EF >35% (7% versus 5% per year; HR, 1.10; P=0.68). Figure 3 presents the unadjusted Kaplan–Meier analysis of death after first generator replacement stratified by LVEF at generator replacement.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier analysis of death after generator replacement stratified by the presence or the absence of continuing indication for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy. EF indicates ejection fraction.

Sixty patients (23.7%) died after first ICD replacement without ever experiencing an appropriate ICD therapy. The cumulative incidence of death without ICD therapy was 4%, 11%, 14%, and 23% at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years of follow-up, respectively.

Statistically significant predictors of mortality on univariate analysis included age, history of atrial fibrillation, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, stroke or transient ischemic attack, higher New York Heart Association functional class, prolonged QRS duration, reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate, elevated blood urea nitrogen, and reduced hemoglobin (Table 4). The use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or aldosterone receptor blocker showed a trend toward lower mortality, and lower serum sodium showed a trend toward higher mortality although these did not meet statistical significance. Statistically significant predictors of mortality in multivariable analysis using stepwise selection included a history of atrial fibrillation (HR, 3.24 [1.63–6.43]; P<0.001) and higher blood urea nitrogen (HR, 1.28 [1.14–1.45] per increment of 10 mg/dL; P<0.001; Table 5).

Table 4. Univariate Predictors of Mortality After Generator Replacement.

| Risk Factor | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per increment of 1 y) | 1.05 | 1.03–1.07 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2.58 | 1.37–4.84 | 0.003 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.90 | 1.86–4.51 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.73 | 1.06–2.82 | 0.029 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 2.26 | 1.39–3.65 | 0.001 |

| NYHA functional class (per increase in NYHA class of 1) |

1.66 | 1.21–2.28 | 0.002 |

| QRS duration (per increment of 10 ms) | 1.08 | 1.03–1.13 | 0.003 |

| Hemoglobin (per decrement of 1 g/dL) | 1.32 | 1.17–1.49 | <0.001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (per decrement of 10 mL/min 1.73 m2) |

1.18 | 1.08–1.29 | <0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (per increment of 10 mg/dL) |

1.23 | 1.13–1.34 | <0.001 |

| Serum sodium (per decrement of 10 mEq/L) |

1.79 | 0.94–3.38 | 0.07 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB therapy | 0.61 | 0.35–1.07 | 0.08 |

ACE/ARB indicates angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/aldosterone receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; and NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Table 5. Predictors of Mortality After Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Generator Replacement in Multivariable Analysis.

| Risk Factor | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.24 | 1.63–6.43 | <0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (per increment of 10 mg/dL) |

1.28 | 1.14–1.45 | <0.001 |

CI indicates confidence interval; and HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

This study describes mortality and appropriate ICD therapy after ICD replacement in primary prevention recipients without a previous history of appropriate ICD therapy. Twenty-eight percent of patients had an LVEF of >35% at the time of replacement, no longer meeting the initial implant criteria. Although persistently depressed EF predicted future therapies, even in the subgroup of patients whose EF had increased to >35% at the time of generator replacement, ventricular arrhythmias requiring appropriate therapies were relatively common—5% per year. These data suggest that the risk of ventricular arrhythmia associated with LV systolic dysfunction does not completely abate even with functional recovery such that great care should be taken in discontinuing ICD therapy.

Professional society guidelines classify primary prevention ICD indications based on randomized trials of first-time ICD implantation.4 However, clinical trials have not been performed to assess the benefit of ICD replacement after first pulse generator depletion when the device did not discharge and the cardiac condition seems to have improved. This study addressed this gap in the current evidence base.

We found that the first ever ICD therapy for ventricular arrhythmia occurred in 23% of patients within 2 years of generator replacement. This figure is comparable with rates reported after first device implantation in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT II) randomized trial (24% during 2 years).13 Our cohort, however, had a higher incidence of ICD therapy than that reported in the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) (22% during 4 years), likely reflecting the higher percentage of patients with infarct-related cardiomyopathy (82%) in our study compared with SCD-HeFT (48%).1,14 The incidence of appropriate ICD therapy for ventricular arrhythmia was significantly higher in patients with persistently low LVEF, with continued divergence of Kaplan–Meier curves in the years after device replacement. The risk of ventricular arrhythmias has previously been reported to remain elevated and constant for several years after initial ICD implantation in patients with low EF.15 This persistent risk seems to extend to patients after generator replacement in our study. Moreover, observations from the MADIT II trial demonstrate that the survival benefit with ICD therapy increases with time in patients with a remote myocardial infarction, so that in patients with EF ≤30% even 15 years after an myocardial infarction, substantial benefit remains.16

A significant number of patients with LVEF to >35% received appropriate ICD therapy for ventricular tachyarrhythmias after generator replacement. These findings reinforce the limitations of using LVEF alone for prediction of sudden cardiac death.17,18 Additional markers, such as inducibility of ventricular tachycardia or magnetic resonance imaging, to identify and quantify fibrosis may be useful and should be investigated. Our data support the replacement of ICD generator in patients who continue to have a reduced LVEF of ≤35% even in the absence of previous appropriate therapy. In patients who have LVEF >35%, the observed rate of appropriate therapy of 4% per year is in the range for which guidelines recommend ICD therapy for many conditions.14,19,20 In the absence of other significant patient factors or preferences, it would, therefore, seem reasonable to proceed with generator replacement in these patients.

This study provides the most comprehensive assessment of the role of repeat EF measurement before ICD replacement to date. Similar to findings in this study, Zhang et al have reported improvement in EF to >35% in 25% of primary prevention ICD recipients with a reduced incidence of ICD therapies in patients with EF improvement.21 Kini et al22 also reported a lower incidence of ICD therapy after ICD replacement in patients with improvement in EF to >40% (2.8% versus 10.7% per person-year). In contrast to these observations, LVEF improvement during follow-up was not predictive of reduced appropriate ICD therapy in primary prevention recipients in the Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation trial (DEFINITE) and in a cohort of ICD replacement patients.23,24 These studies are, however, limited by the absence of EF measurement in a significant proportion of patients, potentially introducing bias in the assessment of outcomes.

Patients undergoing replacement of devices that are infected or under advisory had device replacement sooner after implantation compared with those with battery depletion. These patients were included in this study because they are at particularly high risk of procedural complications and hence need a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits.25,26 The variable period of time between implantation and replacement, however, may bias the results because of varying opportunity to have experienced an appropriate therapy or have improvement in EF. The rate of appropriate ICD therapy stratified by the quartile of time from implantation to replacement, however, was comparable in this study. Lead revision was undertaken at the time of generator replacement in 16% of the cohort. Because lead revision carries a higher risk for periprocedural complications, knowledge of the effect of LVEF on incidence of future therapies is important to the discussion of the risks and benefits of such a procedure.

Significant predictors of mortality in our study were atrial fibrillation and elevated blood urea nitrogen. LVEF, however, was not significantly associated with mortality. Although definition of the cause of death in these patients may provide insights into this finding, these data were not reliably available in this cohort. Previous studies have consistently shown the importance of cardiac diseases, such as atrial fibrillation and heart failure, and noncardiac comorbidities, including renal dysfunction, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and pulmonary disease in predicting mortality after initial ICD implantation and generator replacement.27–31 Our data reinforce the importance of considering both cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities in the decision to replace an ICD generator.

Limitations

Our study has the limitations of a retrospective observational study. The decision to replace an ICD may be biased by several clinical factors and patients who opted not to undergo ICD replacement were not included in this study. The effects of the ICD replacement procedure itself could have influenced the results although these effects would be expected to be balanced between the comparison groups in this study. Moreover, factors associated with improvement in LVEF may also directly influence the outcomes of interest. Although we adjusted for known confounders using statistical methods, there may be unknown confounders that we could not account for. The lack of a control population without ICD replacement also limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions on the mortality benefit of ICD replacement. Hence, large multicenter prospective controlled studies are needed to determine factors associated with benefit from ongoing ICD therapy. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, the time frame between the diagnosis of cardiomyopathy, first ICD implantation, and subsequent improvement in EF could not be ascertained. The adequacy of medical therapy before ICD implantation was also not available. However, only patients who were judged to have a primary prevention indication by the implanting physician, including previous adequate medical therapy and no recent revascularization, were included. The lower rates of therapy with β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and angiotensin receptor blocker in the group with EF >35% could have influenced the rate of appropriate therapy noted in this group. Finally, ICD therapy for ventricular arrhythmia does not equate to aborted sudden death and is influenced by device programming.32 Device programming was noted to vary between patients and was reflective of clinical practice at the time of the study. More recently, a reduction in the rate of ICD therapy and mortality was shown with programming of higher rate zone and longer detection interval in primary prevention ICD recipients.33 Future studies are required to evaluate the outcomes with the newer programming parameters. The occurrence of ICD therapies is, however, indicative of the continued presence of a substrate for ventricular arrhythmias despite improvement in EF.

Conclusions

Among primary prevention ICD recipients who have never received appropriate ICD therapy and require ICD generator replacement, the degree of LV systolic dysfunction modulates the risk of future ICD therapy. In patients with LVEF >35%, the risk of ventricular arrhythmia is sufficiently high (5% per year) to reasonably consider ICD replacement. LVEF was, however, not correlated with survival after generator replacement. Future prospective research on stratification of likelihood of benefit from ICD replacement should focus on identifying factors that clearly identify an increased risk of arrhythmic death out of proportion to overall mortality.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death improves survival in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) ≤35%.

Generator changes of existing ICDs now account for 40% of ICD procedures. Outcomes in patients who do not experience appropriate ICD therapy during the lifetime of the first generator and have subsequent improvement in left ventricular EF to >35% could inform the decision to replace the ICD.

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS

At ICD generator replacement, EF was >35% in 28% of patients without previous appropriate ICD therapy.

Patients with EF >35% continue to experience appropriate ICD therapy after generator replacement (5% per year) although at a lower rate than patients with a persistently low EF (12% per year).

Acknowledgments

Dr Kramer was supported by a Paul Beeson Career Development Award in Aging Research (K23AG045963). Dr Buxton was supported by a research grant from Medtronic, Inc, with no personal compensation. Dr Friedman serves on advisory boards for Medtronic and Boston Scientific. He has served on a clinical trial steering committee for St. Jude Medical.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH, Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) Investigators Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Klein H, Levine JH, Saksena S, Waldo AL, Wilber D, Brown MW, Heo M, Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial Investigators Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1933–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352601. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML, Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, 3rd, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hammill SC, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Newby LK, Page RL, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Faxon DP, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices) American Association for Thoracic Surgery. Society of Thoracic Surgeons ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices) developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:e1–e62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.032. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo AM, Stainback RF, Bailey SR, Epstein AE, Heidenreich PA, Jessup M, Kapa S, Kremers MS, Lindsay BD, Stevenson LW. ACCF/HRS/AHA/ASE/HFSA/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2013 appropriate use criteria for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation appropriate use criteria task force, Heart Rhythm Society, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Failure Society of America, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1318–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.017. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kremers MS, Hammill SC, Berul CI, Koutras C, Curtis JS, Wang Y, Beachy J, Blum Meisnere L, Conyers del M, Reynolds MR, Heidenreich PA, Al-Khatib SM, Pina IL, Blake K, Norine Walsh M, Wilkoff BL, Shalaby A, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld J. The National ICD Registry Report: version 2.1 including leads and pediatrics for years 2010 and 2011. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:e59–e65. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.01.035. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saxon LA, Hayes DL, Gilliam FR, Heidenreich PA, Day J, Seth M, Meyer TE, Jones PW, Boehmer JP. Long-term outcome after ICD and CRT implantation and influence of remote device follow-up: the ALTITUDE survival study. Circulation. 2010;122:2359–2367. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.960633. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.960633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer DB, Buxton AE, Zimetbaum PJ. Time for a change–a new approach to ICD replacement. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:291–293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer DB, Kennedy KF, Noseworthy PA, Buxton AE, Josephson ME, Normand SL, Spertus JA, Zimetbaum PJ, Reynolds MR, Mitchell SL. Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving new and replacement implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results from the NCDR. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:488–497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000054. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krahn AD, Lee DS, Birnie D, Healey JS, Crystal E, Dorian P, Simpson CS, Khaykin Y, Cameron D, Janmohamed A, Yee R, Austin PC, Chen Z, Hardy J, Tu JV, Ontario ICD Database Investigators Predictors of short-term complications after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator replacement: results from the Ontario ICD Database. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:136–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poole JE, Gleva MJ, Mela T, Chung MK, Uslan DZ, Borge R, Gottipaty V, Shinn T, Dan D, Feldman LA, Seide H, Winston SA, Gallagher JJ, Langberg JJ, Mitchell K, Holcomb R, REPLACE Registry Investigators Complication rates associated with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator generator replacements and upgrade procedures: results from the REPLACE registry. Circulation. 2010;122:1553–1561. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976076. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moss AJ, Greenberg H, Case RB, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Brown MW, Daubert JP, McNitt S, Andrews ML, Elkin AD, Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-II (MADIT-II) Research Group Long-term clinical course of patients after termination of ventricular tachyarrhythmia by an implanted defibrillator. Circulation. 2004;110:3760–3765. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000150390.04704.B7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000150390.04704.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, Anderson J, Callans DJ, Raitt MH, Reddy RK, Marchlinski FE, Yee R, Guarnieri T, Talajic M, Wilber DJ, Fishbein DP, Packer DL, Mark DB, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1009–1017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alsheikh-Ali AA, Homer M, Maddukuri PV, Kalsmith B, Estes NA, 3rd, Link MS. Time-dependence of appropriate implantable defibrillator therapy in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:784–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01111.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilber DJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Brown MW, Lin AC, Andrews ML, Burke M, Moss AJ. Time dependence of mortality risk and defibrillator benefit after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:1082–1084. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121328.12536.07. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121328.12536.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahnve S, Gilpin E, Henning H, Curtis G, Collins D, Ross J., Jr Limitations and advantages of the ejection fraction for defining high risk after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58:872–878. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(86)80002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Hafley GE, Pires LA, Fisher JD, Gold MR, Josephson ME, Lehmann MH, Prystowsky EN, MUSTT Investigators Limitations of ejection fraction for prediction of sudden death risk in patients with coronary artery disease: lessons from the MUSTT study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.095. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barsheshet A, Wang PJ, Moss AJ, Solomon SD, Al-Ahmad A, McNitt S, Foster E, Huang DT, Klein HU, Zareba W, Eldar M, Goldenberg I. Reverse remodeling and the risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in the MADIT-CRT (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2416–2423. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.041. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F, Charron P, Hagege AA, Lafont A, Limongelli G, Mahrholdt H, McKenna WJ, Mogensen J, Nihoyannopoulos P, Nistri S, Pieper PG, Pieske B, Rapezzi C, Rutten FH, Tillmanns C, Watkins H. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the task force for the diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2733–2779. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Guallar E, Blasco-Colmenares E, Butcher B, Norgard S, Nauffal V, Marine JE, Eldadah Z, Dickfeld T, Ellenbogen KA, Tomaselli GF, Cheng A. Changes in follow-up left ventricular ejection fraction associated with outcomes in primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and cardiac resynchronization therapy device recipients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.057. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kini V, Soufi MK, Deo R, Epstein AE, Bala R, Riley M, Groeneveld PW, Shalaby A, Dixit S. Appropriateness of primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillators at the time of generator replacement: are indications still met? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2388–2394. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.025. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schliamser JE, Kadish AH, Subacius H, Shalaby A, Schaechter A, Levine J, Goldberger JJ, DEFINITE Investigators Significance of follow-up left ventricular ejection fraction measurements in the Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation trial (DEFINITE) Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:838–846. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.02.017. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yap SC, Schaer BA, Bhagwandien RE, Kühne M, Dabiri Abkenari L, Osswald S, Szili-Torok T, Sticherling C, Theuns DA. Evaluation of the need of elective implantable cardioverter-defibrillator generator replacement in primary prevention patients without prior appropriate ICD therapy. Heart. 2014;100:1188–1192. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305535. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gould PA, Krahn AD, Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Working Group on Device Advisories Complications associated with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator replacement in response to device advisories. JAMA. 2006;295:1907–1911. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.16.1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.16.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prutkin JM, Reynolds MR, Bao H, Curtis JP, Al-Khatib SM, Aggarwal S, Uslan DZ. Rates of and factors associated with infection in 200 909 Medicare implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implants: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circulation. 2014;130:1037–1043. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alba AC, Braga J, Gewarges M, Walter SD, Guyatt GH, Ross HJ. Predictors of mortality in patients with an implantable cardiac defibrillator: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:1729–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.024. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilchick KC, Stukenborg GJ, Kamath S, Cheng A. Prediction of mortality in clinical practice for medicare patients undergoing defibrillator implantation for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1647–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.028. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldenberg I, Vyas AK, Hall WJ, Moss AJ, Wang H, He H, Zareba W, McNitt S, Andrews ML, MADIT-II Investigators Risk stratification for primary implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.058. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee DS, Tu JV, Austin PC, Dorian P, Yee R, Chong A, Alter DA, Laupacis A. Effect of cardiac and noncardiac conditions on survival after defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2408–2415. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.058. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer DB, Kennedy KF, Spertus JA, Normand SL, Noseworthy PA, Buxton AE, Josephson ME, Zimetbaum PJ, Mitchell SL, Reynolds MR. Mortality risk following replacement implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation at end of battery life: results from the NCDR. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.10.046. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Germano JJ, Reynolds M, Essebag V, Josephson ME. Frequency and causes of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies: is device therapy proarrhythmic? Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1255–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.048. doi: 10.1016/j. amjcard.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss AJ, Schuger C, Beck CA, Brown MW, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Estes NA, 3rd, Greenberg H, Hall WJ, Huang DT, Kautzner J, Klein H, McNitt S, Olshansky B, Shoda M, Wilber D, Zareba W. Reduction in inappropriate therapy and mortality through ICD programming. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2275–2283. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]