Abstract

Calcitonin is the hallmark of medullary thyroid carcinoma. However, extrathyroidal neuroendocrine tumors can also release calcitonin.

We report 2 cases of calcitonin-secreting pancreatic tumors found in asymptomatic patients with thyroid nodules referred to our center within 11 months.

Case 1: A man initially referred for thyroid nodule characterization was found to have hypercalcitoninemia (>200 pg/mL) during non-neoplastic fine-needle aspiration.

Case 2: A woman evaluated for liver metastasis was found to have hypercalcitoninemia and multinodular goiter.

Our research emphasizes that marked hypercalcitoninemia in the presence of thyroid nodules is not necessarily due to medullary thyroid carcinoma; awareness of this could avoid unnecessary thyroidectomy. The lack of specific symptoms related to hypercalcitoninemia may be the reason that the prevalence of calcitonin-secreting pancreatic tumors is underestimated.

INTRODUCTION

High circulating calcitonin levels are associated with medullary thyroid carcinoma.1 However, several other neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) can also release calcitonin, including pheochromocytomas, neuromas and lung, breast, prostate, and colorectal carcinomas.2,3 Calcitonin-secreting pancreatic endocrine tumors (CTsPETs) have been described as extremely rare.4 We report 2 consecutive cases of CTsPETs found during the evaluation of patients with hypercalcitoninemia and thyroid nodules. These cases highlight the risk of underestimating calcitonin as a tumor marker for pancreatic NET.

CASE REPORTS

Written informed consent was obtained from both patients for the publication of this manuscript and accompanying images.

Case 1

A 53-year-old Caucasian man was referred to our department for an elevated serum calcitonin level (253 pg/mL, reference range 0–10) discovered during an evaluation of thyroid nodules. The patient was asymptomatic and was not taking any medication; his family history included only lung cancer, in his father. Blood testing showed polycythemia vera, for which he underwent periodic blood tests. TSH, FT3, and FT4 were normal and thyroid antibodies negative. Color Doppler ultrasound (CDUS) revealed 2 non-homogeneous thyroid nodules of 0.6 and 1.8 cm, with a medium elastography pattern (3B and 2 respectively). Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) suggested benign hyperplastic nodules (Thy 2, British Thyroid Association, BTA-RCP 2007); calcitonin measurement in fine needle wash-out of both thyroid nodules was negative (1.24 and 1.68 pg/mL respectively). Serum electrolytes, PTHi, 24-h urinary metanephrines (144 mcg/24 h < 345) and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA = 8.0 mg/24 h <13.6) were normal.

Hypercalcitoninemia was confirmed in 2 further samples (388 and 443 pg/mL). We started an extensive search for extrathyroidal causes of hypercalcitoninemia. NET markers were normal: neuron-specific enolase (NSE) (5 ng/mL <10), gastrin (50 pg/mL <120), chromogranin A-CgA (44 ng/mL <90), CEA (1.5 ng/mL <5), VIP (12 pmol/L <30), 5HT+5HTP (4.0 mg/24 h <5), PSA (0.65 ng/mL <2.3), and 24-h urinary 5HIAA (3.0 mg/24 h <6). Gastroscopy and prostate US were negative. Abdominal computed tomography showed a pancreatic nodule (1.8 cm) with moderate enhancement during arterial phase, confirmed on magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 1A) as suggestive of NET. An integrated nuclear medicine approach was undertaken (A.B.): 18F-DOPA PET/CT (Figure 1B - lower panel) revealed mild pancreatic metabolization while 18F-FDG PET/CT (Figure 1B - upper panel) and OctreoScan +SPECT/CT were negative.

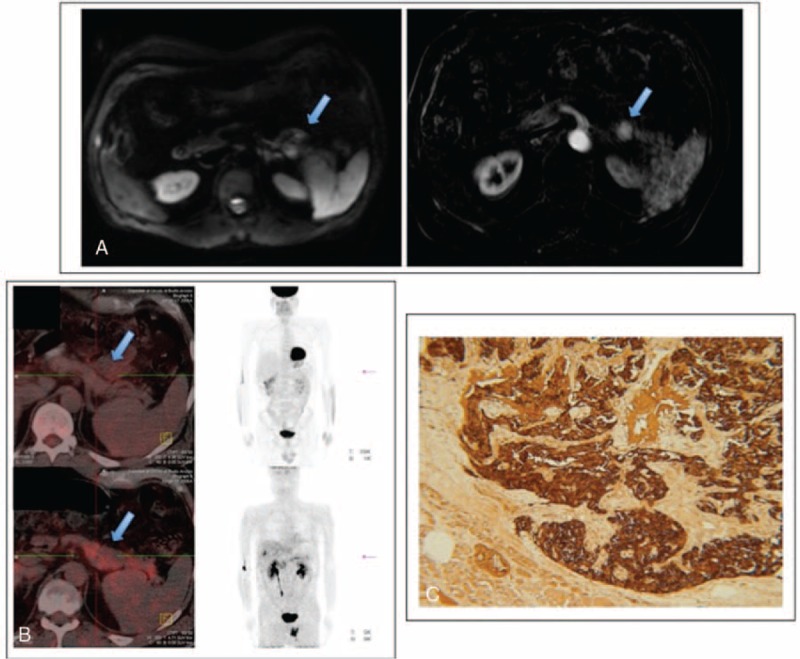

FIGURE 1.

MRI, 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, and immunostaining for calcitonin in Case 1. A, MRI scan shows a solid 18-mm lesion in the pancreatic tail (arrows), which appears hypointense on T1 and slightly hyperintense on T2. Contrast-enhanced sequences show hypervascularity in arterial phase with persistent enhancement in the subsequent phases. B, 18F-FDG PET/CT (in the upper part of the panel) and 18F-DOPA PET/TC (in the lower part of the panel) both show no significant metabolic activity in the pancreatic lesion. C, Immunostaining of the pancreatic nodule shows intense calcitonin staining (brown). MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

The patient underwent a distal pancreatectomy (P.C.) that confirmed a well-differentiated NET (2.3 cm, G1, proliferation index 2%) which was positive for calcitonin, NCAM, CgA, synaptophysin, NSE immunostaining (Figure 1C) and negative for insulin, glucagon, gastrin, somatostatin, and serotonin.

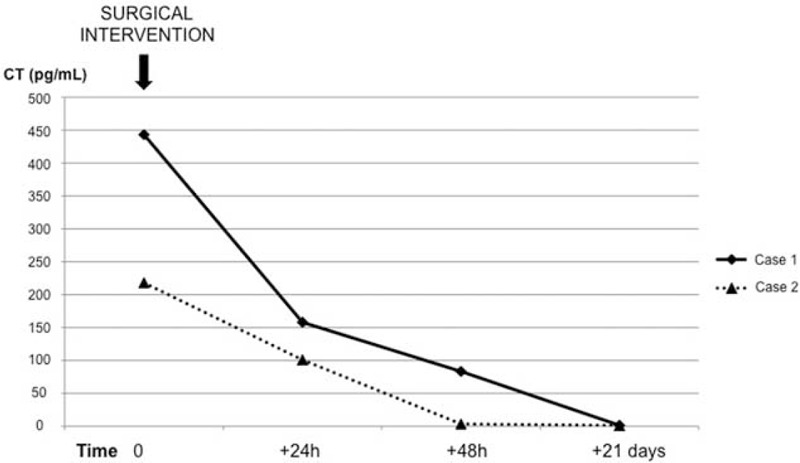

Calcitonin gradually normalized after surgery (Figure 2); prolonged follow-up (24 months) showed repeatedly normal calcitonin levels, confirming disease eradication. Genetic testing for MEN1 (exons 2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10) and RET (exons 10,11,13,14,15,16) mutations associated with CTsPETs were negative.

FIGURE 2.

Time course of postsurgical calcitonin normalization (solid: Case 1; open: Case 2).

Case 2

A 78-year-old Caucasian woman with a 5-month history of vague abdominal discomfort and constipation complained of a recent onset gastric pain and underwent a liver US, which found 2 suspect non-homogeneous lesions (1.6 and 0.6 cm) in liver segment VII. The patient had known thyroid nodules and was referred for endocrine evaluation. Her brother had died from hepatic metastases from a tumor of unknown origin. The patient was not taking any medications. Before admission she had an abdominal computed tomography scan, which revealed a nodule (4.0 cm) in the pancreatic tail, and a 18F-FDG PET/CT scan, that was negative. NET marker screening showed: hypercalcitoninemia (126 pg/mL: n.v. 0–10), confirmed in 2 subsequent measurements (122 and 218 pg/mL), with normal NSE (4 ng/mL <10), gastrin (64 pg/mL <120), CgA (75 ng/mL <90), CEA (1.79 ng/mL <5), VIP (20 pmol/L <30), 5HT+5HTP (4.0 mg/24 h <5), and 24-h urinary 5HIAA (4.0 mg/24 h <6). Thyroid hormones and antibodies were normal. Thyroid CDUS confirmed 2 hypoechoic nodules (1.2 and 1.7 cm) with a medium (3A) elastography pattern. FNAC showed benign hyperplastic nodules (Thy 2) with unremarkable calcitonin levels in needle wash-out. Serum electrolytes, PTHi, and 24-h urinary metanephrines (53.0 mcg/24 h) and VMA (6.0 mg/24 h) were normal.

The patient underwent US-guided biopsy of the hepatic lesion that was consistent with metastasis from a well-differentiated NET (panCKAE1/AE3+, CK8/18+, CK7-, CK20-, Synaptophysin+, NSE+/-, CgA-/+, HepPar1-, alfaFP-, TTF1-, CDX2-, Calcitonin-; Ki67 staining <3%). The patient underwent a distal pancreatectomy and liver metastasectomy (P.C.). Histopathology revealed a well-differentiated 5.0-cm pancreatic NET with angioinvasion (G1, proliferation index 2%), with immunostaining positive for calcitonin, NCAM, CgA, synaptophysin and NSE and negative for glucagon, gastrin, insulin, somatostatin, and serotonin. Calcitonin levels normalized rapidly post-surgery (+24 h = 101 pg/mL; +48 h = 3.62 pg/mL; +21 days = 1.31 pg/mL) (Figure 2). Genetic testing was negative.

The patient is currently doing well and is followed up regularly in the outpatient clinic.

DISCUSSION

The discovery of 2 cases of CTsPETs within 11 months in our center suggests that extrathyroid calcitonin secretion by NET could be more common than generally thought.5–8 The absence of specific symptoms (except for a vague abdominal discomfort) is problematic for both identification of the source and post-operative monitoring.

Several extrathyroidal tumors can produce ectopic calcitonin, including pheochromocytomas, pancreatic NETs, adrenocortical carcinomas, NETs of esophagus, acute leukemia, lung cancers, cervical tumors, prostatic carcinomas, breast cancers, renal carcinomas, gastrointestinal tract tumors.3 In all these tumors, the anatomic localization, rapid growth, and frequent cosecretion of other hormones (including ACTH, gastrin, catecholamines, and somatostatin) drive the clinical presentation and allow rapid localization of the source.9–11

Symptoms of pancreatic NET can include diarrhea, which has been associated with cosecretion of somatostatin8 or the histological nature of the tumor.7 However, neither of our patients complained of diarrhea.

In contrast, isolated ectopic calcitonin secretion has not been associated with a specific clinical picture and can remain silent, meaning patients are unlikely to seek medical help.

The lack of emphasis on differential diagnosis leads to general unawareness of CTsPETs and some cases probably remain undiagnosed.

Case 1 suggests that elevated calcitonin levels should be investigated with care even in the presence of thyroid nodules, and especially when the nodules have few suspicious features; the pancreas should be screened first. In fact, if not promptly diagnosed, CTsPETs can metastasize, as in Case 2.

Calcitonin measurement should be included in the work-up of any neuroendocrine pancreatic lesion, with or without metastases, even if metastases can lose secretory activity, probably as they dedifferentiate (Case 2).6 Calcitonin has proved sensitive in various paraneoplastic syndromes.11,12

Herein, we showed 2 cases with positive immunostaining for calcitonin in PETs in which serum calcitonin decay (24 h, 48 h, and 21 days) was helpful in postsurgical surveillance. Nuclear medicine imaging supported the diagnosis and the combined morphological/functional imaging provided by hybrid PET/CT scan offered the best guide for surgery.13 In both cases, the absence of glucose metabolism in the pancreatic lesions supported the diagnosis of biologically nonaggressive CTsPETs.

In Case 1, the lack of F-DOPA fixation in the thyroid strengthened the suspicion of an extrathyroid calcitonin secretion, already suggested by the negative calcitonin measurement in FNAC needle wash.14 Of note was that the pancreatic nodule failed to metabolize F-DOPA consistently, with low aromatic amino acid decarboxylase activity (false negative). Octreoscan was negative, suggesting low or negative SSTR-2 expression; unfortunately the more sensitive 68Gallium-DOTATOC-PET scan was not performed.11

The negative genetic tests suggest the sporadic nature of these pancreatic lesions.

In conclusion, when calcitonin levels are elevated and thyroid examination is not clearly suggestive of medullary thyroid carcinoma or C-cell hyperplasia, general screening of extrathyroidal calcitonin secretion is recommended. CTsPET should be suspected in the differential diagnosis, especially in view of the lack of specific symptoms, that may further delay diagnosis. Routine serum calcitonin measurement may be a highly sensitive adjunct to identify a subset of CTsNETs, and calcitonin monitoring may enable early detection and postoperative surveillance.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Marie-Hélène Hayles for revision of the English text.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CDUS = color doppler ultrasound, CgA = chromogranin A, CTsPET = calcitonin-secreting pancreatic tumors, FNAC = fine needle aspiration cytology, MTC = medullary thyroid carcinoma, NETs = neuroendocrine tumors, NSE = neuron-specific enolase, VMA = vanillylmandelic acid.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheung K, Roman SA, Wang TS, et al. Calcitonin measurement in evaluation of thyroid nodules in the United States: a cost-effectiveness and decision analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93:2173–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cvijovic G, Micic D, Kendereski A, et al. Ectopic calcitonin secretion in a woman with large cell neuroendocrine lung carcinoma. Hormones (Athens) 2013; 12:584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz KE, Wolfsen AR, Forster B, et al. Calcitonin in nonthyroidal cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1979; 49:438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider R, Waldmann J, Swaid Z, et al. Calcitonin-secreting pancreatic endocrine tumors: systematic analysis of a rare tumor entity. Pancreas 2011; 40:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson B, Arnberg H, Lindgren PG, et al. Neuroendocrine pancreatic tumours: clinical presentation, biochemical and histopathological findings in 84 patients. J Intern Med 1990; 228:103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Brandi ML, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: functional pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes. Neuroendocrinology 2012; 95:98–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kováčová M, Filková M, Potočárová M, et al. Calcitonin-secreting pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a case report and review of the literature. Endocr Pract 2014; 20:e140–e144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Do Cao C, Mekinian A, Ladsous M, et al. Hypercalcitonemia revealing a somatostatinoma. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2010; 71:553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asa SL, Kovacs K, Killinger DW, et al. Pancreatic islet cell carcinoma producing gastrin, ACTH, alpha-endorphin, somatostatin and calcitonin. Am J Gastroenterol 1980; 74:30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamberts SW, Hackeng WH, Visser TJ. Dissociation and association between calcitonin and adrenocorticotropin secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1980; 50:565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isidori AM, Sbardella E, Zatelli MC, et al. Conventional and nuclear medicine imaging in ectopic Cushing's syndrome: a systemic review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:3231–3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isidori AM, Kaltsas GA, Pozza C, et al. The ectopic adrenocorticotropin syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, management, and long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudczak R. Traub-Weidinger T: PET and PET/CT in endocrine tumours. Eur J Radiol 2010; 73:481–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boi F, Maurelli I, Pinna G, et al. Calcitonin measurement in wash-out fluid from fine needle aspiration of neck masses in patients with primary and metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92:2115–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]