Abstract

Nocardia infection is not common in clinical practice and most cases occur as an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients.

We report a case of primary cutaneous nocardiosis characterized by multiple subcutaneous abscesses due to Nocardia brasiliensis in a patient with nephrotic syndrome undergoing long-term corticosteroid therapy. The patient was diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome 9 months ago, and mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis was confirmed by renal biopsy. Subsequently, his renal disease was stable under low-dose methylprednisolone (8 mg/d). All of the pus cultures, which were aspirated from 5 different complete abscesses, presented Nocardia. Gene sequencing confirmed that they were all N. brasiliensis. The patient was cured by surgical drainage and a combination of linezolid and Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole.

The case highlights that even during the period of maintenance therapy with low-dose corticosteroid agents, an opportunistic infection still could occur in patients with nephrotic syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with nephrotic syndrome are at high risk of infections, including primary peritonitis, sepsis, cellulitis, chickenpox.1,2 A retrospective review of 351 children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome disclosed 24 episodes of peritonitis in 19 patients.3Streptococcus pneumoniae was the most common agent (50%), and Escherichia coli remained popular (25%). Four cases (16%) were culture-negative. Opportunistic infections in patients with nephrotic syndrome, caused by cryptococcus,4cytomegalovirus,5toxoplasmosis,6cryptosporidia,7 and Nocardia, have also been reported.8Nocardia are aerobic, filamentous gram-positive, atypical acid-fast bacteria that are rarely encountered in immunosuppressed patients, which can cause a rare localized or systemic suppurative disease.9,10 Human infection occurs either by direct skin inoculation or by inhalation in immunocompromised patients.11 Here, we present a case of primary cutaneous nocardiosis in a patient undergoing low-dose immunosuppression therapy without a known history of percutaneous injury.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

This case report has been approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People's Hospital. A consent form was obtained.

In July of 2015, a 63-year-old man with 9-month history of nephrotic syndrome was admitted to Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital because of multiple subcutaneous abscesses with intermittent fever for 20 days. Twenty days prior to admission, 2 subcutaneous abscesses presented on his left lower limb.

The subcutaneous abscesses then sequentially spread from the primary infection to the right dorsal hand, the chest wall, the abdominal wall, the left elbow, and the right lower limb. The abscesses appeared as firm and nonfluctuant masses initially, then they gradually grew up and manifested as tender, fluctuant, and erythematous nodules. They were 0.5 to 5 cm in diameter. Some abscesses ruptured and oozed yellow pus. The patient also developed intermittent chills and fever up to 39.7°C. The patient had been admitted to another hospital 15 days before. He was empirically treated with levofloxacin, ceftriaxone, metronidazole, and surgical drainage there. After half a month with no improvement, he was transferred to our hospital.

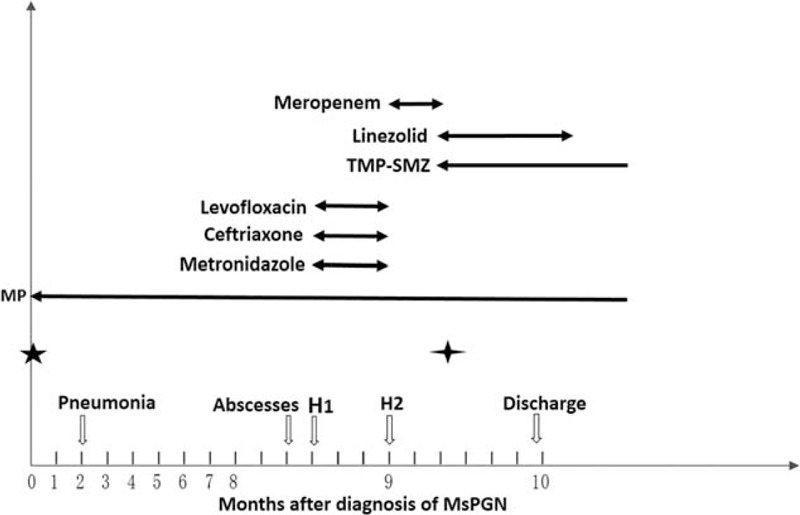

Medical history: The patient was diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome 9 months ago, and mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis was confirmed by renal biopsy. He was initially treated with oral methylprednisolone (48 mg/d) and got a remission. Subsequently, his renal disease was stable with a creatinine clearance of 104 mL/min and minimal proteinuria (220 mg/24 h) under low-dose methylprednisolone (8 mg/d). He had developed diabetes after receiving steroids 7 months before this admission. At that time, he also got pneumonia and recovered with empirical antibiotic treatment. He had a history of hypertension and chronic HBV infection. The patient's social and family history were not remarkable.

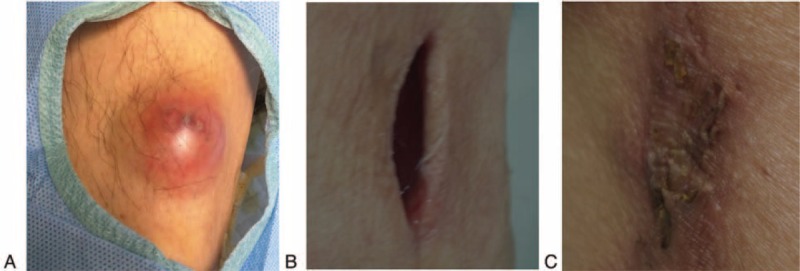

Physical examination: On admission, T (temperature) 39.5°C, PR (pulse rate) 80/min, RR (respiratory rate) 14/min, BP (blood pressure) 120/81 mm Hg. More than 10 scattered subcutaneous abscesses were found (Figure 1A), and some ruptured or incised abscesses (Figure 1B) with yellowish purulent discharge were observed. The cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurologic examinations were unremarkable.

FIGURE 1.

Changes of the abscesses after treatments. A, A subcutaneous abscess on left lower limb. B, The incised abscess with purulent discarge. C, The abscess disappeared following treatment.

Lab test: A complete blood count showed a white blood cell (WBC) of 17.5 × 109/L with 88.4% neutrophils. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 97 mm/h↑, Procalcitonin 0.340 ng/mL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 130.00 mg/L↑. 24 h urine protein: 0.22 g. Serum markers of HIV, syphilis, tuberculosis (TB) were all negative. Serum HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBe were positive. Immunology: Antinuclear antigen (ANA), anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm, anti-SSA, anti-SSB and anti-Scl-70: negative. Serum levels of IgG, IgA, IgM, IgE were within normal limits. Serum C3 0.85 g/L↓, serum C4 0.33 g/L, anti-O: 119.00 IU/ML and serum rheumatoid factor (RF) <9.75 IU/ML. Subset of lymphocytes was almost normal: CD3+ 85.04%, CD4+ 45.01%, CD4+/CD8+ 1.13, CD8+ 39.90%, natural killer (NK) cells 7.97%, CD19+ 5.93%. Immunoelectrophoresis results were normal and M-protein was negative. Liver function tests and the chest radiograph were negative. Ultrasound on sites of abscesses: Subcutaneous anechoic lesions. Blood culture was performed, but it did not yield growth of any bacteria after incubation. In addition, HBsAg and HBeAg staining were both negative on the renal biopsy. There were some infiltrated lymphocytes, but no granulomas were found. Moreover, nocardia was not found on the renal biopsy by wade fite staining

Treatment: The multiple abscesses were incised and drained. Before identification of the pathogen, we used meropenem empirically. Meanwhile, culture of pus was ordered. All of the pus cultures, which were aspirated from 5 different complete abscesses, presented Nocardia consistently, and gene sequencing (Figure 2) confirmed that they were all N. brasiliensis. Further investigations for disseminated disease, including computed tomography of the chest and the brain, were negative. According to drug susceptibility testing, linezolid and TMP-SMX were employed as antibiotic therapy. In addition, the immunosuppression treatment was not halted at the time of nocardia presentation. After 1 week's treatment, his fever resolved. Three weeks later, the abscesses disappeared, and the incisions or wounds had healed (Figure 1C). The WBC and neutrophils count also went down. After 4 weeks of hospitalization, he was sent home on a 6-month course of oral TMP-SMX therapy. He remains well off all treatments, without recurrence. The clinical course is summarized in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Gene sequence of N. braisiliensis identified from the pus.

FIGURE 3.

Clinical course.

DISCUSSION

Nocardiosis is a rare localized or systemic suppurative disease caused by several species of bacteria of the genus Nocardia.9Nocardia are aerobic, filamentous gram-positive, partially acid-fast bacteria belonging to the Actinomycetales order.10 More than 100 species of Nocardia have been identified by using the 16S RNA gene sequencing, and over 30 of them produce illnesses in humans.12Norcardia are found in soil, decayed organic matter, water, and air worldwide.11 Human infection occurs either by direct skin inoculation or by inhalation.11 Then, they can cause pulmonary, central nerve systemic, skin, or systemic infection.13 The majority of Nocardia infections occur in immunocompromised people.10

Cutaneous nocardiosis is an uncommon infectious disease that presents a primary cutaneous infection or as a part of disseminated pulmonary nocardiosis.14 Primary cutaneous nocardiosis can present as lymphocutaneus syndrome, superficial skin infection (pustules, pyroderma, abscess, ulcers, granulomas, or cellulitis), sialoadenitis, and mycetoma.8,15–18 The most common cause of primary cutaneous nocardiosis is N. brasiliensis.10 Direct inoculation through the skin is the main route for infection of N. brasiliensis, while direct inhalation of contaminated particles containing this bacterium may also occur.16 In this case, the patient did not have a known history of percutaneous inoculation. So the pathogen may first be achieved by inhalation, and then disseminated to skin.

Differential diagnosis were as follows:

Hidradenitis suppurativa: a chronic, suppurative process involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue; recurrent, painful, and inflamed nodules that then rupture and diacharge purulent material; the most common site is interginous skin such as the axilla, the inguinal area, and inner thighs.19,20

Spototrichosis: a cutaneous and subcutaneous chronic infection caused by Sporothrix schenckii; associated with inoculation of soil through the skin; manifests as local pustule or ulcer with nodules along draining lymphatics.21

Tularemia: ulceroglandular disease presents as fever and a single erythematous papulo-ulcerative lesion with a central eschar at the site of a tick bite in affected patients. The skin lesion is accompanied by tender regional lymphadenopathy.22

The cutaneous suppurative manifestation caused by Nocardia is hard to differentiate clinically from cutaneous infection produced by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. Furthermore, most cutaneous infections are empirically treated without a bacteriologic diagnosis. However, this patient had been treated with levofoxacin, ceftriaxsone, metronidazole in another hospital, without any effects. Taking his long-term corticosteroid therapy history into consideration, we were cautious of opportunistic infection by rare pathogens. So, we performed a culture. The abscesses turned out to be caused by N. brasiliensis, an opportunistic pathogen. He was undergoing long-term oral methylprednisolone because of nephrotic syndrome. However, the dosage had reduced from 48 to 8 mg/d as a maintenance therapy. As we know, the occurrence of an opportunistic infection following the reduction of the steroid dose is not very common.23 Our case highlights that even during the period of maintenance therapy with low dosage corticosteroid, patients still could undergo opportunistic infections.

As the intermittent high fever and chills raised the suspicion of bacteremia and septicemia, blood culture was performed, but it did not yield growth of any bacteria after incubation. In fact, Nocardia bacteremia is a rare occurrence. Although disseminated nocardiosis was presumed to occur via hematogenous spread, capture of the organism in blood cultures was unusual.24 The only unique risk factor for bacteremia is an endovascular foreign body such as a central venous catheter.25

In conclusion, patients with nephrotic syndrome who are undergoing corticosteroid therapy could have a rare opportunistic infection, such as nocardiosis, even during the period of maintenance therapy with a low-dose corticosteroid. It is vital to identify the pathogen by culture and choose sensitive antibiotics with the help of drug susceptibility testing. Early therapy with an adequate dosage of antibiotics for enough time is the key to curing such patients.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANA = antinuclear antigen, BP = blood pressure, CRP = C-reactive protein, ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate, MsPGN = mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, NK = natural killer cells, PR = pulse rate, RF = rheumatoid factor, RR = respiratory rate, TB = tuberculosis, TMP-SMX = trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, T = temperature.

BC and JT contributed equally to this work.

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570603) and Shanghai talents development fund and Shanghai Pujiang Talent Projects (15PJ1406700).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park SJ, Shin JI. Complications of nephrotic syndrome. Korean J Pediatr 2011; 54:322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang F, Wang N, Li J. Analysis on the infection among patients with nephrotic syndromes and systemic vasculitis treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Clin Rheumatol 2010; 29:1073–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krensky AM, Ingelfinger JR, Grupe WE. Peritonitis in childhood nephrotic syndrome: 1970–1980. Am J Dis Child 1982; 136:732–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Qunpeng H, Shutian X, et al. Fatal primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: case report and review of published literature. Ir J Med Sci 2015; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez-Lluva MT, de la Nieta-Garcia MD, Piqueras-Flores J, et al. Chlorambucil-induced cytomegalovirus infection: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrios JE, Duran Botello C, Gonzalez Velasquez T. Nephrotic syndrome with a nephritic component associated with toxoplasmosis in an immunocompetent young man. Colomb Med (Cali) 2012; 43:226–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrikhande SN, Chande CA, Shegokar VR, et al. Pulmonary cryptosporidiosis in HIV negative, immunocompromised host. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2009; 52:267–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu T, Furumoto H, Asagami C, et al. Disseminated subcutaneous Nocardia farcinica abscesses in a nephrotic syndrome patient. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38 (5 Pt 2):874–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerner PI. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 22:891–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87:403–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaman BL, Beaman L. Nocardia species: host-parasite relationships. Clin Microbiol Rev 1994; 7:213–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen KW, Lu CW, Huang TC, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Nocardia brasiliensis infection in Taiwan during 2002-2012-clinical studies and molecular typing of pathogen by gyrB and 16S gene sequencing. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 77:74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matulionyte R, Rohner P, Uckay I, et al. Secular trends of nocardia infection over 15 years in a tertiary care hospital. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57:807–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vijay Kumar GS, Mahale RP, Rajeshwari KG, et al. Primary facial cutaneous nocardiosis in a HIV patient and review of cutaneous nocardiosis in India. Indian J Sex Transm Dis 2011; 32:40–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paredes BE, Hunger RE, Braathen LR, et al. Cutaneous nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis after an insect bite. Dermatology 1999; 198:159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smego RA, Jr, Gallis HA. The clinical spectrum of Nocardia brasiliensis infection in the United States. Rev Infect Dis 1984; 6:164–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satterwhite TK, Wallace RJ., Jr Primary cutaneous nocardiosis. JAMA 1979; 242:333–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuda H, Saotome A, Usami N, et al. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: a case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J Dermatol 2008; 35:346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:539–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Zee HH, Laman JD, Boer J, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: viewpoint on clinical phenotyping, pathogenesis and novel treatments. Exp Dermatol 2012; 21:735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kauffman CA. Sporotrichosis. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 29:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans ME, Gregory DW, Schaffner W, et al. Tularemia: a 30-year experience with 88 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985; 64:251–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou L, Liu H, Yuan F, et al. Disseminated nocardiosis in a patient with nephrotic syndrome following HIV infection. Exp Ther Med 2014; 8:1142–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lederman ER, Crum NF. A case series and focused review of nocardiosis: clinical and microbiologic aspects. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:300–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Akhrass F, Hachem R, Mohamed JA, et al. Central venous catheter-associated Nocardia bacteremia in cancer patients. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:1651–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]