Abstract

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans infection is a rare and easily misdiagnosed ocular disease. In this article, the authors report a chronic, purulent, and difficult-to-treat case of A actinomycetemcomitans keratitis following a glaucoma infiltration surgery.

A 56-year-old man with a long-standing history of open-angle glaucoma in both eyes presented with a 12-week history of ocular pain, redness, and blurred vision in his right eye. He underwent a glaucoma infiltration surgery in his right eye 6 months ago. Three months postoperatively, he developed peripheral corneal stromal opacities associated with a white, thin, cystic bleb, and conjunctival injection. These opacities grew despite topical treatment with topical tobramycin, levofloxacin, natamycin, amikacin, and metronidazole eye drops.

Multiple corneal scrapings revealed no organisms, and no organisms grew on aerobic, anaerobic, fungal, or mycobacterial cultures. The patient's right eye developed a severe purulent corneal ulcer with a dense hypopyon and required a corneal transplantation. Histopathologic analysis and 16S ribosomalribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction sequencing revealed A actinomycetemcomitans as the causative organism. Postoperatively, treatment was initiated with topical levofloxacin and cyclosporine, as well as oral levofloxacin and cyclosporine. Graft and host corneal transparency were maintained at the checkup 1 month after surgery.

Although it is a rare cause of corneal disease, A actinomycetemcomitans should be suspected in patients with keratitis refractory to topical antibiotic therapy. Delay in diagnosis and appropriate treatment can result in vision loss.

INTRODUCTION

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a rare cause of infection in humans that locates in the periodontal pocket and leads to damage to the tooth-supporting tissues.1 Although its prevalence in the general population is rather high, it has mainly been reported in cases of endocarditis and aggressive periodontal disease.2–4 For eye diseases, A actinomycetemcomitans can be a rare cause of endogenous endophthalmitis, especially in an immune-suppressed condition.2,5 There have been rare reports of Actinomyces-induced delayed-onset keratitis following penetrating keratoplasty6 and laser in situ keratomileusis.7 In this article, we report on an unusual case of Actinomyces keratitis following a glaucoma infiltration surgery, which was eventually diagnosed by histopathologic analysis and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) gene sequencing and successfully treated with corneal transplantation.

METHOD

This was a case report. The Institutional Review Board of the Shanghai Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital, Fudan University, approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

CLINICAL REPORT

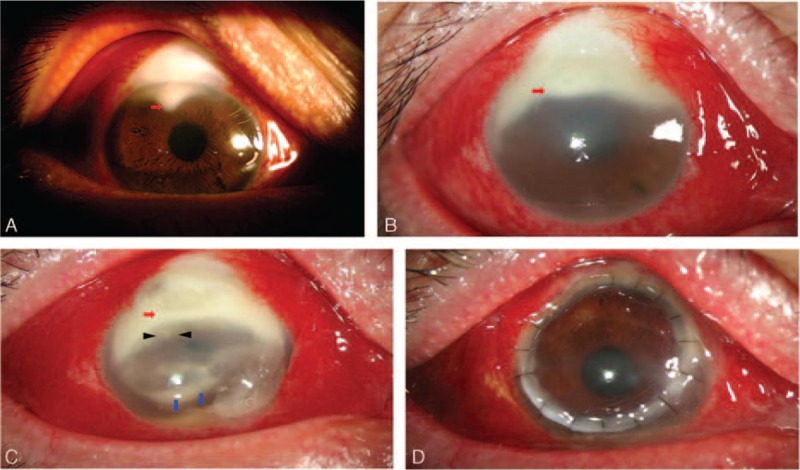

A 56-year-old man without any ophthalmic or systemic diseases was referred to our cornea service with a 12-week history of ocular pain, redness, and blurred vision in his right eye. He was a government officer and had a long-standing history of open-angle glaucoma in both eyes. Six months ago, he underwent an uncomplicated glaucoma infiltration surgery on his right eye with an implantation by an EX-PRESS glaucoma filtration device. The best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of the right eye was 20/25 and 20/32 before and 1 month after surgery, respectively. Correspondingly, the intraocular pressure (IOP) was 28 and 15 mm Hg, respectively. Since then, he was followed-up monthly, with good control of his IOP in the right eye. Three months postoperatively, he developed peripheral corneal stromal opacities associated with a white, thin, cystic bleb, and conjunctival injection (Figure 1A). The cornea was clear; however, without any notable anterior chamber reaction was noted. The posterior segment examinations (including fundoscopy and ultrasound) were normal. His BCVA and IOP were 20/25 and 16 mm Hg, respectively. Thus, under the diagnosis of microbial keratitis, he received corneal scrapping for Gram stain and acid-fast stain. Aerobic, anaerobic, fungal, or mycobacterial cultures were performed, but no organisms were identified. Owing to his peripheral corneal opacity and conjunctival congestion, he was treated for bacterial keratitis. Topical eye drops, including 0.3% tobramycin and 0.5% levofloxacin, were applied hourly. After a 1-week course of antibiotics, the corneal and conjunctival signs had not resolved, so 0.5% natamycin eye drops 4 times per day was added for treating possible fungal keratitis. Unfortunately, the ocular conditions continued to worsen.

FIGURE 1.

Clinical slit lamp examination of Actinomyces keratitis at the initial visit (A), after 12-week antibiotics treatments (B), after 1-week course with a new antibiotics regimen (C), and 1 month after penetrating keratoplasty (D). Red arrows indicate peripheral corneal opacity, black arrows indicate satellite infiltrates, and blue arrows indicate anterior chamber hypopyon.

Ten weeks later, the patient was referred to our Ophthalmology Department for further management. By this time, the corneal opacities had grown, and marked conjunctival injection and a moderate anterior chamber inflammatory reaction had developed (Figure 1B). The BCVA of the patient's right eye had already decreased to 20/400. We repeated corneal scraping and microbial cultures and again found no organisms. Nocardia or anaerobic keratitis was suspected, so the patient was prescribed with a 1-week course of topical 0.4% amikacin and 0.5% metronidazole eye drops every 2 hours. His ocular conditions, however, worsened further and a peripheral epithelial defect with a diffuse peripheral whitish corneal stromal infiltrate associated with satellite infiltrates was observed (Figure 1C). Five days later, his right eye developed a severe purulent corneal ulcer. His visual acuity in the right eye was light perceptive, indicating visual loss. Not only the size and depth of the peripheral corneal ulcer increased but also endothelium plaques and anterior chamber hypopyon were noted (Figure 1D).

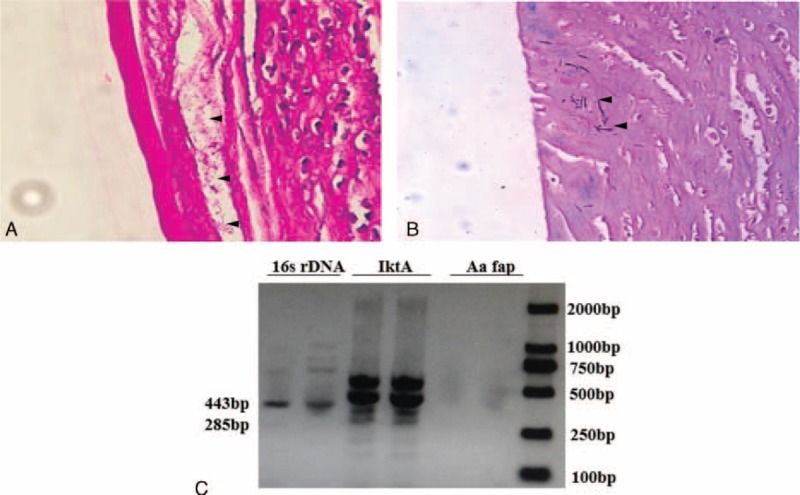

To control the ocular conditions and to prevent possible endophthalmitis, we performed a penetrating keratoplasty on his right eye. Histopathologic analysis of the removed cornea revealed intense corneal inflammation associated with intrastromal colonies of strongly and uniformly gram-positive bacteria with short, stubby branches typical of Actinomyces species (Figure 2A). Acid-fast staining was negative, suggesting Actinomyces rather than mycobacteria (Figure 2B). We performed the third microbial laboratory examination, and finally detected the microbe from a corneal biopsy specimen by using a molecular genetic method. We performed molecular identification by PCR amplification and 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis using deoxyribonucleic acid extracted from the corneal biopsy specimen (Figure 2C). The universal primers for the Actinomyces species, including 16S rRNA gene in a 443 bp length (forward, 5′-GCTAATACCGCGTAGAGTCGG-3′; reverse, 5′-ATTTCACACCTCACTTAAAGGT-3′), leukotoxin gene in a 285 bp length (forward, 5′-TCGCGAATCAGCTCGCCG-3′; reverse, 5′-GCTTTGCAAGCTCCTCACC-3′), and fimbria-associated protein gene in a 210 bp length (forward, 5′-ATTAAATACTTTAACTACTAAAGC-3′; reverse, 5′-GCACTGTTAACTGTACTAGC-3′), were used as described previously.8 Polymerase chain reaction results revealed that the causative organism in our patient was caused by 16S ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid+, leukotoxin+, and fimbria-associated protein− A actinomycetemcomitans.

FIGURE 2.

Laboratory examinations of Actinomyces keratitis. Histopathologic analysis revealed filamentous, branching, gram-positive bacteria (black arrow) in the deep corneal stroma consistent with Actinomyces species with intense corneal inflammation, showing staining with hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification ×400) (A) and acid fast stain (original magnification ×400) (B). Polymerase chain reaction products from corneal specimens revealed that the causative organism in this patient was caused by 16S ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid+, leukotoxin+, and fimbria-associated protein− Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (C).

Postoperatively, the patient was given topical 0.5% levofloxacin (6 times/d) and 0.1% cyclosporine (4 times/d) in conjunction with oral levofloxacin (500 mg/d) and cyclosporine (5 mg/kg/d). After a 1-month treatment period, there was no evidence of recurrence and the corneal graft remained transparent with a functional bleb. The patient recovered a BCVA of 20/63 with good control of IOP.

DISCUSSION

A actinomycetemcomitans is an exceedingly rare type of the ocular infection. Only a handful of previous reports have considered it as the causative agent for endogenous endophthalmitis.2,5,9,10 In addition, although microbial keratitis is an important cause of monocular blindness worldwide,11,12 reports about the corneal involvements of A actinomycetemcomitans are limited. Patients with Actinomyces keratitis could be found after ocular trauma,13 undergoing keratoplasty6 or laser in situ keratomileusis.7 This could be because of the trauma itself, loose corneal sutures or the routine usage of topical immunosuppressive drugs after ocular surgery.

This is the first reported case of keratitis caused by A actinomycetemcomitans. Randomized controlled clinical trials have been conducted to determine the most favorable antibiotic regimen for treating A actinomycetemcomitans. Systemic levofloxacin and moxifloxacin improve the clinical outcomes of periodontitis and suppress A actinomycetemcomitans below detectable levels.14,15 In our case, the antibiotic resistance to levofloxacin before the corneal transplantation, however, was contrary to these reports, but was consistent with histopathologic results; this revealed that the infection focus was located in the deep corneal stroma, leading to poor corneal drug penetration and a low antibiotics concentration. Similarly to an Actinomyces-induced keratitis case after keratoplasty,6A actinomycetemcomitans was difficult to eradicate medically in our case, and required surgical intervention.

During the whole course of the disease, the conjunctival bleb induced by the glaucoma infiltration surgery remained intact, without any hyperemia, indicating that bleb leakage may not have been the reason for the pathogen invasion. We did not perform the microbial cultures or pathologic analysis on the glaucoma implantation device. It, however, is hard to attribute the infection to the device because the patient had been recovering well until 2 months after the glaucoma surgery. The exact etiology of this patient remains elusive. One may be concerned about why we did not perform corneal biopsy for this patient. Indeed, we did consider performing the corneal biopsy at the early stage. Before the first bacterial cultures, his visual acuity, however, was good (20/25) and the corneal epithelial layer was intact (Figure 1A), so we decided to perform corneal scraping only. By the second bacterial cultures, we have already recommended a corneal biopsy for this patient. But the patient refused this invasive procedure, because he was worried about the exacerbation of the disease. We note that the lesion of this patient was located in the deep stroma (Figure 2B), which makes it hard for clinicians to obtain a positive biopsy sample.

The wide variety of regimens for the treatment of microbial keratitis highlights the need for individual management. Before finding a definitive evidence of the pathogen, most eye care providers, however, make the clinical decision based on risk factors for infection, severity and duration of onset, and last medical history. Even without any positive laboratory results, we suspected our case to be microbial keratitis from the beginning. The patient's early treatment reflected the typical regimen prescribed by most glaucoma specialists, combining fortified topical antibiotics with coverage of the most common bacteria and fungi. Because of the failure of this empirical therapy, treatment protocols for nocardia or anaerobic keratitis, however, were considered, yet these, too, proved to be ineffective. In the end, our case responded only to surgical interventions with wide boundaries for the complete removal of the focus. Corneal cross-linking has been proven to be an effective adjuvant therapy in the management of severe infectious keratitis with corneal melting.16 Its application to deep stromal keratitis, however, is still under debate.17,18 Future studies are warranted to investigate whether this novel technique could be used for treating A actinomycetemcomitans keratitis.

In conclusion, this is the first report to our knowledge of A actinomycetemcomitans keratitis diagnosed by histopathologic analysis and PCR with 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and successfully treated with corneal transplantation. We suggest that in patients with keratitis refractory to topical fortified antibiotic therapy, A actinomycetemcomitans should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Polymerase chain reaction with 16S rRNA gene sequencing might be a quick, cost-effective diagnostic tool for suspected microbial keratitis with negative cultures results.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BCVA = best-corrected visual acuity, fap = fimbria-associated protein, IOP = intraocular pressure, lktA = leukotoxin, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, rRNA = ribosomal RNA.

The authors were supported by grants from the Key Clinic Medicine Research Program, the Ministry of Health, China (201302015); the National Science and Technology Research Program, the Ministry of Science and Technology, China (2012BAI08B01); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81170817, 81200658, 81300735, 81270978, U1205025, and 81330022); the Scientific Research Program, Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality, Shanghai (13441900900, 13430720400); the Chinese Postdoctoral Fund (XMU135890); and the New Technology Joint Research Project in Shanghai Hospitals (SHDC12014114).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haubek D, Johansson A. Pathogenicity of the highly leukotoxic JP2 clone of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and its geographic dissemination and role in aggressive periodontitis. J Oral Microbiol 2014; 6.doi: 10.3402/jom.v6.23980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishak MA, Zablit KV, Dumas J. Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Can J Ophthalmol 1986; 21:284–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kozlovsky A, Wolff A, Saminsky M, et al. Effect of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans from aggressive periodontitis patients on Streptococcus mutans. Oral Dis 2015; 21:955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norskov-Lauritsen N. Classification, identification, and clinical significance of haemophilus and aggregatibacter species with host specificity for humans. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27:214–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binder MI, Chua J, Kaiser PK, et al. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans endogenous endophthalmitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis 2003; 35:133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shtein RM, Newton DW, Elner VM. Actinomyces infectious crystalline keratopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2011; 129:515–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karimian F, Feizi S, Nazari R, et al. Delayed-onset Actinomyces keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis. Cornea 2008; 27:843–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu YM, Yan J, Chen LL, et al. Association between infection of different strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in subgingival plaque and clinical parameters in chronic periodontitis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2007; 8:121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lass JH, Varley MP, Frank KE, et al. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans endophthalmitis with subacute endocarditis. Ann Ophthalmol 1984; 16:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donzis PB, Rappazzo JA. Endogenous Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans endophthalmitis. Ann Ophthalmol 1984; 16:858–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prajna NV, Mascarenhas J, Krishnan T, et al. Comparison of natamycin and voriconazole for the treatment of fungal keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol 2010; 128:672–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma N, Sachdev R, Jhanji V, et al. Therapeutic keratoplasty for microbial keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2010; 21:293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh M, Kaur B. Actinomycetic corneal ulcer. Eye 1989; 3:460–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pradeep AR, Singh SP, Martande SS, et al. Clinical and microbiological effects of levofloxacin in the treatment of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-associated periodontitis: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Int Acad Periodontol 2014; 16:67–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ardila CM, Martelo-Cadavid JF, Boderth-Acosta G, et al. Adjunctive moxifloxacin in the treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis patients: clinical and microbiological results of a randomized, triple-blind and placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42:160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Said DG, Elalfy MS, Gatzioufas Z, et al. Collagen cross-linking with photoactivated riboflavin (PACK-CXL) for the treatment of advanced infectious keratitis with corneal melting. Ophthalmology 2014; 121:1377–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uddaraju M, Mascarenhas J, Das MR, et al. Corneal cross-linking as an adjuvant therapy in the management of recalcitrant deep stromal fungal keratitis: a randomized trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2015; 160:131–134.e135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richoz O, Moore J, Hafezi F, et al. Corneal cross-linking as an adjuvant therapy in the management of recalcitrant deep stromal fungal keratitis: a randomized trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2015; 160:616–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]