Abstract

Concerns remain regarding the heterogeneity in overlapping human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk behaviors among sex workers (SWs) in Pakistan; specifically, the degree to which SWs interact with people who inject drugs (PWID) through sex and/or needle sharing.

Following an in-depth mapping performed in 2011 to determine the size and distribution of key populations at highest risk of HIV acquisition in Pakistan, a cross-sectional biological and behavioral survey was conducted among PWID, female (FSWs), male (MSWs), and hijra/transgender (HSWs) sex workers, and data from 8 major cities were used for analyses. Logistic regression was used to identify factors, including city of residence and mode of SW-client solicitation, contributing to the overlapping risks of drug injection and sexual interaction with PWID.

The study comprised 8483 SWs (34.5% FSWs, 32.4% HSWs, and 33.1% MSWs). Among SWs who had sex with PWID, HSWs were 2.61 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19–5.74) and 1.99 (95% CI, 0.94–4.22) times more likely to inject drugs than MSWs and FSWs, respectively. There was up to a 3-fold difference in drug injecting probability, dependent on where and/or how the SW solicited clients. Compared with SWs in Larkana, the highest likelihood of drug injection use was among SWs in Multan (OR = 4.52; 95% CI: 3.27–6.26), followed by those in Lahore, Quetta, and Faisalabad.

Heterogeneity exists in the overlapping patterns of HIV risk behaviors of SWs. The risk of drug injection among SWs also varies by city. Some means of sexual client solicitation may be along the pathway to overlapping HIV risk vulnerability due to increased likelihood of drug injection among SWs. There is a need to closely to monitor the mixing patterns between SWs and PWID and underlying structural factors, such as means of sexual client solicitation, that mediate HIV risk, and implement prevention programs customized to local subepidemics.

INTRODUCTION

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic in Pakistan is concentrated among key populations (KPs), including sex workers (SWs) and people who inject drugs (PWID).1–5 Stigmatized populations in Pakistan, such as PWID and SWs, engage in drug injection and transactional sex underground, limiting their access to services and subjecting them to harassment and violence.6–8 Understanding important aspects of HIV transmission dynamics is required to facilitate containment of the epidemic. This includes understanding risk behaviors of each KP, as well as mixing patterns among and between KPs.

The prevalence of opiate drug use has been estimated at 0.7% among the adult population in Pakistan.9 Recent studies have demonstrated that HIV in Pakistan is concentrated largely among PWID, with an estimated prevalence of 11.0% in 2004, increasing steadily to 27.2% by 2011.1 There is geographic variation in HIV prevalence among PWID in Pakistan. In 2011, this ranged from 19.2% in Sukkur to 30.7% in Lahore, 43.0% in Karachi, and 52.5% in Faisalabad.2,4,10,11 Although HIV prevalence is concentrated mainly among PWID in Pakistan,1,3,10,12–15 there is a concern that the virus is expanding to their sexual contacts, particularly SWs.2–4,10,16 This in turn may lead to the spread from SWs, through their non-PWID clients, to the general population.

In addition to having sexual clients who are PWID, a significant proportion of SWs may inject drugs,3,4 increasing their risk of HIV exposure.17 Thus, the potential for a substantial increase in transmission within networks of SWs and their clients exists7,16,18,19 consistent with the pattern of HIV epidemics in other countries in Asia, whereby HIV transmission begins among PWID and subsequently spreads to SWs and their clients.20–24

Understanding heterogeneity in mixing patterns among KPs in concentrated HIV epidemics may help in the design of more effective intervention strategies.1,3,4,11,17 For example, the degree to which SWs interact, either through sex or drug injection, with PWID, may play a major role in the variation of observed epidemiological patterns of HIV transmission.1,3,4,7,23,24 Similarly, multiple risk behaviors within individuals are considered to be one of the factors fueling the rapid spread of HIV in South and South East Asia,1,3,7,24 and a similar situation may exist in Pakistan. Using cross-sectional, integrated biological and behavioral surveillance (IBBS) data collected among KPs in 2011,2 the objectives of this study were to assess the heterogeneity in overlapping HIV risk behaviors among SWs, specifically the degree to which SWs interact with PWIDs through sex and/or needle sharing, and to identify factors associated with drug injection risk vulnerability among SWs in Pakistan.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Populations

The IBBS data for this study were collected by the Canada–Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project from March 2011 to September 2011. The data collected among KPs were from 17 cities in Pakistan. The 8 cities with data available among all KPs were included in this analysis. These cities are Lahore, Faisalabad, Multan, Sargodha, Karachi, Sukkur, Larkana, and Quetta.

IBBS was conducted following an in-depth mapping of KPs aimed to estimate the SW population size in each city.3,25,26 The KPs mapped and surveyed in each city were male (MSW), female (FSW), hijra/transgender (HSW) sex workers, and PWID. Inclusion criteria included selling sex in exchange for money or other benefits, and age 13 or older among MSWs, and 15 or older among FSWs and HSWs. Evidence from previous IBBS data suggests that many MSWs start sex work at a younger age than FSWs or HSWs, and therefore the age limit for inclusion in the 2011 MSWs sample was lowered to 13 years. PWID refer to persons aged 18 or older who had injected drugs for nontherapeutic purposes in the past 6 months. Further details of the IBBS methods, including the sampling design and how study participants of each KP in each city were recruited, have been described previously.2–4,10,11,25 In this study, we describe SW risk behavior and mixing patterns, specifically their mixing with PWID.

Study Measures

Among SWs, the main outcomes of interest were overlapping risk behaviors that would link the SW and PWID populations, that is, having vaginal or anal sex with a PWID in the past 6 months, and/or drug injection (at least 1 of the 4 drugs: avil, diazepam, tamgesic, or heroin) in the past 6 months. The heterogeneity in the overlapping of HIV risk behavior among KPs was assessed by examining the likelihood of injecting drugs among SWs, and comparing this likelihood of injecting drugs across SWs who differed in terms of their sexual interaction with PWID in the past 6 months.

In addition to sexual interactions with PWID, we explored several factors that may explain the heterogeneity in the risk of drug injection among SWs. Specifically, we examined socio-demographic indicators, including city of residence, as well as a potential structural or risk-mediating indicator that describes how SWs usually find or communicate with clients. Possible network structures include “network operators” (also called pimps/gurus), roaming around the streets, referral from old clients, and using mobile phones. The potential impact of this structural factor along the pathway to drug injection vulnerability was examined.

Statistical Analysis

We described SWs in terms of how they interacted with PWID. HIV prevalence of each KP was estimated as the number of HIV-infected people divided by the total number of people surveyed in each of the respective KPs. Demographic, geographic, and risk-taking characteristics of study participants were examined descriptively. Mean and standard deviations (SD) of age during interview and the number of years (duration) that people remain in respective KPs as of the time of interview were calculated to further describe study participants.

Bivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors for multivariable analyses that may be significantly related to drug injection. These factors included having had sex with PWID in the past 6 months, the structural indicator of how the SW connects with clients, and socio-demographic indicators including geographic residence. Further analysis was performed to assess the significant interaction effect of any 2 independent variables of interest. Unless otherwise stated, Wald tests were used to select factors that were associated with drug injection at a significance level of P < .10. After variables were assessed independently, multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the impact of included variables on the likelihood of injecting drugs after adjusting for covariates. In the process of examining the impact of variables of interest, some variables were thought a priori to be important, so they were included in multivariable analyses even if not statistically significant in bivariate analyses. These included age, education level, marital status, income, duration in sex work, and HIV status. In all analyses, sampling weights based on the respective estimated population sizes of each KP in each city were utilized in order to account for the complex sampling design used. Weighting was identified as described previously.27–29 All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Ethics Approvals and Study Participant Consent

All participants were interviewed following informed consent and referred for voluntary counselling and HIV testing, postinterview. They were also provided with HIV prevention and service information. HIV test results were linked to the corresponding interview data by an encrypted unique identifier and unique study site; no personal information accompanied the data and only authorized personnel had access to the data files. The study received ethical approval from HOPE International and Public Health Agency of Canada.

RESULTS

A total of 8483 SWs (34.5% FSWs, 32.4% HSWs, and 33.1% MSWs) from 8 major cities from Punjab, Sindh, and Balochistan provinces in Pakistan were included in the study. The mean age of SWs was 26.3 years (SD 6.5), and the mean number of years that they had been in sex work by the time of their interview was 6.2 (SD 5.7).

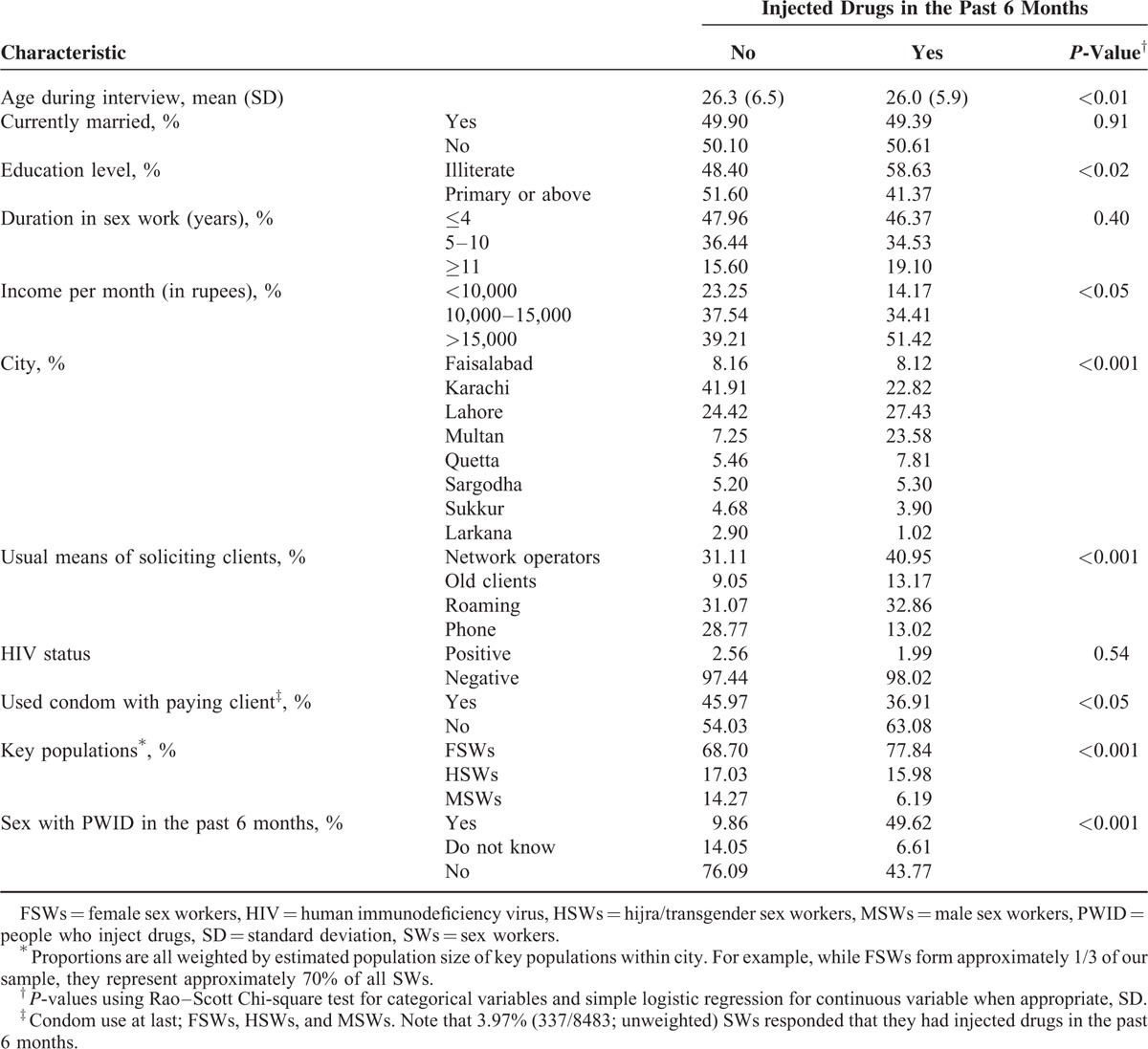

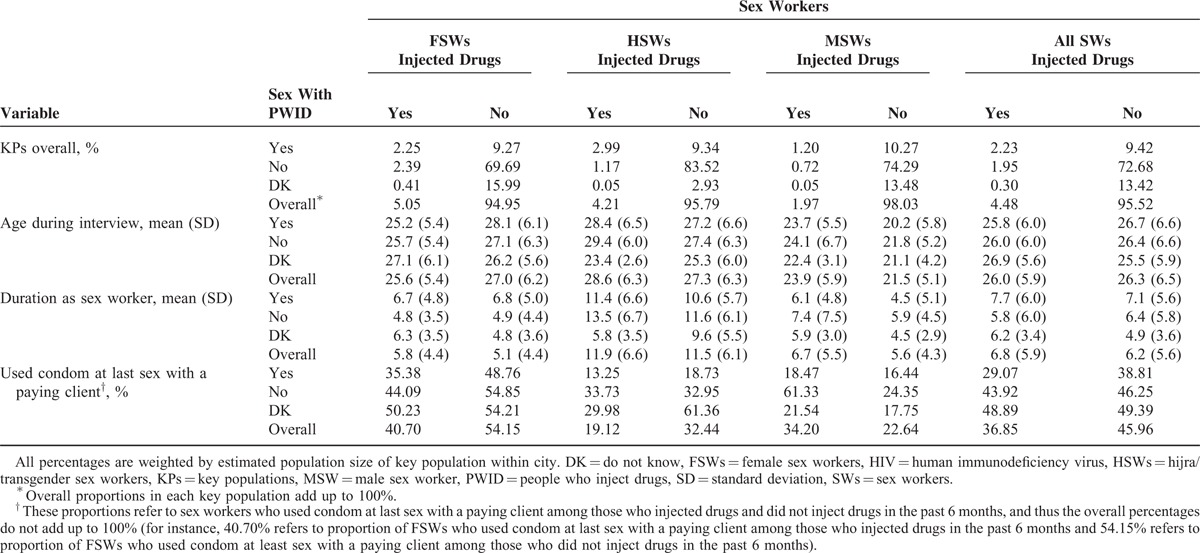

Table 1 displays the distribution of socio-demographic characteristics of SWs in terms of their exposure to drug injection. Table 2 characterizes SWs in terms of overlapping HIV risk behaviors (i.e., injected drugs and/or had sex with a PWID during the past 6 months), their age during interview, and the duration in practicing high-risk behavior. The HIV risks studied were having sex with PWID, injecting drugs, or overlapping risks (both sexual interaction with PWID and drug injection). In total, 2.23% of SWs reported that they were engaged in overlapping risk behaviors (both injecting drugs and having sex with PWID) in the past 6 months. The percentage of SWs who both injected drugs and had sex with PWID in the past 6 months varied by KP. The highest proportion of overlapping risk behaviors were observed among HSWs (2.99%) followed by FSWs (2.25%) and MSWs (1.20%). Among all surveyed, 4.48% of SWs reported that they injected drugs while 11.65% of SWs reported that they had had sex with a PWID in the past 6 months. A total of 13.90% of SWs reported that they had sex with a PWID or injected drugs in the past 6 months. Among the group with at least 1 risk exposure, 16.05% were exposed to overlapping HIV risk, that is, they both injected drugs and had sex with PWID. The proportion with exposure to at least 1 risk behavior, either injecting drugs or having sex with a PWID, was highest among FSWs (14.32%) followed by HSWs (13.55%) and MSWs (12.24%), though the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.25).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Sex Workers∗

TABLE 2.

HIV Risk Behaviors Among Sex Workers in Relation to Their Interaction With People Who Inject Drugs

Table 2 also presents the distribution of age and duration in practicing high-risk behavior among all SWs. Analyses among all PWID (whether or not had sex with SWs in the past 6 months) were also performed for comparison purposes, and results indicated that the overall mean age and duration in practicing drug injection among PWID were estimated at 31.0 years (SD 7.9) and 5.0 years (SD 4.8), respectively. Among PWID who exchanged sex for money, the mean duration in practicing drug injection was 4.1 (SD 3.9). The mean duration of sex work among the population of SWs who injected drugs (mean = 6.8, Table 2) was approximately 2.7 years longer than the mean duration of drug injection among PWID who exchanged sex for money (P < 0.01, independent t-test).

We further explored trends of condom use among SWs. Overall, less than half (45.55%) of SWs used a condom in the last sexual intercourse with any paying client, and this varied from 53.47% among FSWs to 31.87% and 22.87% among HSWs and MSWs, respectively (P < 0.001). In general, those who injected drugs were less likely to use a condom with paying clients (Table 2). Worryingly, those who had sex with a PWID in the past 6 months were also less likely to use a condom with paying clients (Table 2). We were unable to determine specifically whether a condom was used during sex with the PWID.

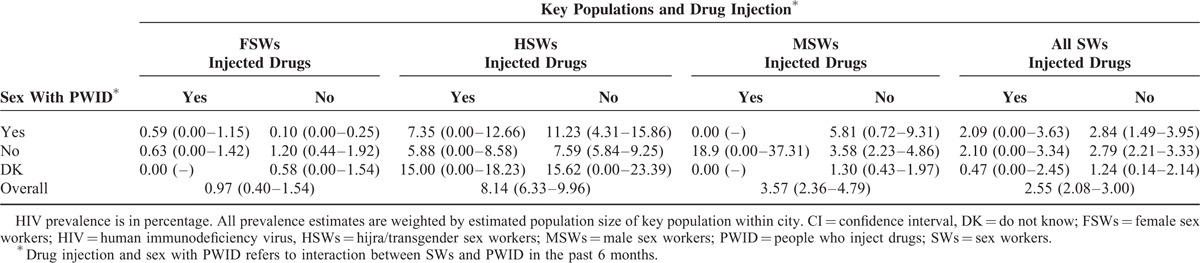

The overall HIV prevalence among SWs was 2.55% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.08–3.00) (Table 3). This varied by SW population, with the highest prevalence among HSWs (8.14%), followed by 3.57% among MSWs and 0.97% among FSWs (P < 0.01, Fisher exact test). The highest HIV prevalence among SWs with at least 1 interactive risk exposure with PWID was observed among SWs who only had sex with PWID, but did not inject drugs (2.84%). This was followed by the prevalence among SWs who only injected drugs but did not have sex with PWID (2.10%) and SWs engaged in overlapping risk (2.09%) (P < 0.05, Fisher exact test for difference between the 3 groups).

TABLE 3.

HIV Prevalence (95% CI) by Pattern of Overlapping HIV Risk Behavior Among SW Populations

There is also variation in HIV prevalence between KPs with respect to the type of risk behavior(s) that SWs engaged in with PWID (Table 3). Among HSWs with known risks, the highest HIV prevalence (11.23%) was observed among those who only had sex with PWID, but did not inject drugs, followed by a prevalence of 7.35% among those with overlapping risk and 5.88% among those who injected drugs, but did not have sex with PWID (P < 0.05, Fisher exact test). Interestingly, although with wide CIs, the highest prevalence among HSWs was found among those who did not know whether they had had sex with a PWID in the past 6 months. Although the highest HIV prevalence among HSWs with known risks was among those who had had sex with a PWID but who did not inject drugs, a contrasting result was found among FSWs and MSWs. That is, among both FSWs and MSWs, those who injected drugs but had not had sex with a PWID in the past 6 months had higher HIV prevalence than those who had had sex with PWID but did not inject drugs (P < 0.05, Fisher exact test). Those SWs exposed to at least 1 risk behavior involving PWID (injecting, or sex with PWID, or both) had a lower overall HIV prevalence (2.56%, not shown in Table 3) than those with no interaction with PWID (2.79%), though the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.26, Fisher exact test).

Logistic Regression Associations With Drug Injection

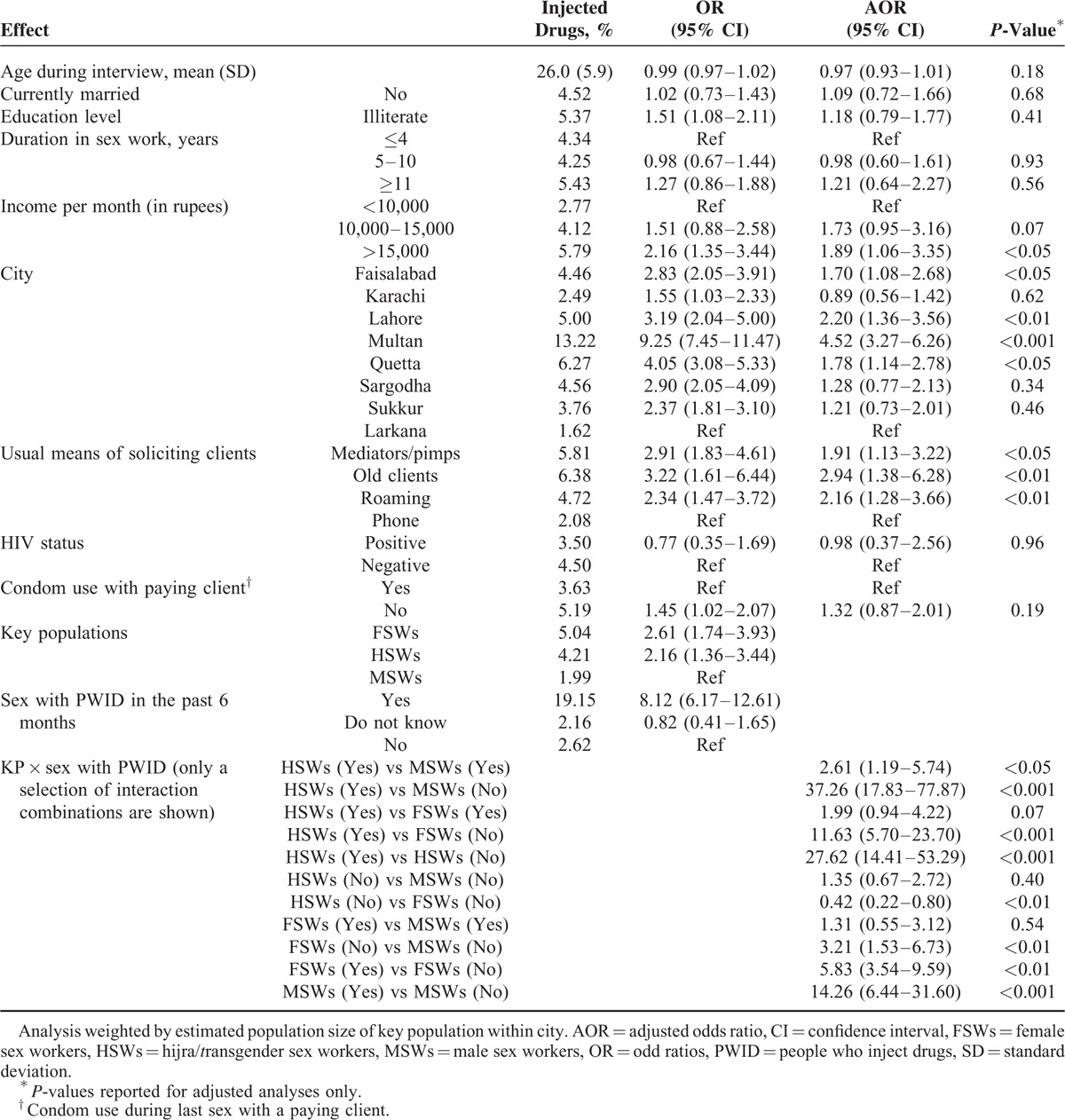

Risk factors associated with drug injection during the past 6 months, after adjusting for potential confounding variables, are presented in Table 4. Income is associated with injection, with those making >15,000 rupees per month being 1.89 (95% CI: 1.06–3.35) times more likely to inject than those making <10,000 rupees per month. Similarly, there is variation in the odds of injecting by city. For example, SWs from Multan and Lahore are 4.52 (95% CI: 3.27–6.26) and 2.20 (95% CI: 1.36–3.56) times more likely to inject than SWs from Larkana. Compared to SWs who recruited their sexual clients using mobile phone, SWs who solicited through a mediator (pimp/network operator), by roaming around in public places, and through old clients were 1.91 (95% CI: 1.13–3.22), 2.16 (95% CI: 1.28–3.66), and 2.94 (95% CI: 1.38–6.28) times more likely to be engaged in drug injection, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Crude odds ratio (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and 95% CI, Reporting the Risk of Injecting Drugs Among Sex Workers

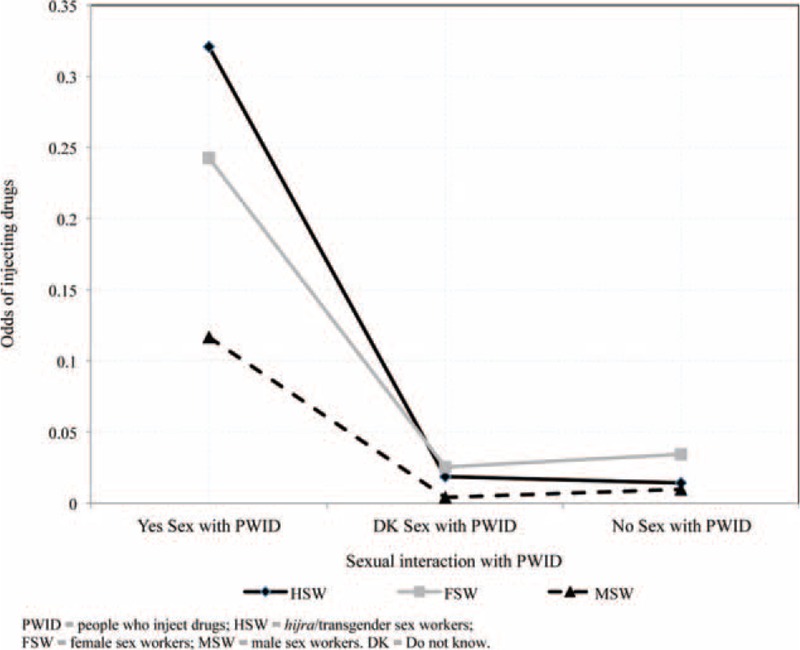

The type of SW (FSWs, HSWs, or MSWs), exposure to sexual interaction with PWID, and the interaction of these 2 factors were significantly associated with drug injection. The adjusted odds ratios comparing interaction groups are displayed in Table 4; to ease interpretation, Figure 1 displays the unadjusted odds of drug injection. Although having had sex with a PWID was significantly associated with having injected drugs across all SWs, the impact varied by SW group. The largest impact of sex with a PWID on having injected drugs was seen among HSWs. Among HSWs, those who had had sex with PWID in the past 6 months were 27.62 (95% CI: 14.41–53.29) times more likely to have injected drugs, compared to HSWs who had no sexual interaction with PWIDs. By contrast, among FSWs and MSWs, those who had had sex with a PWID in the past 6 months were 5.83 (95% CI: 3.54–9.59) and 14.26 (95% CI: 6.44–31.60) times more likely to have injected drugs, respectively, compared to their respective SW group who had no sex with PWID. Among the SWs groups who had sex with PWID in the past 6 months, HSWs were 2.61 (95% CI: 1.19–5.74) and 1.99 (95% CI: 0.94–4.22) times more likely to have injected drugs than MSWs and FSWs, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Unadjusted odds of injecting drugs in the past 6 months, by type of sex worker and sexual activity with people who inject drugs.

DISCUSSION

There is heterogeneity in the overlapping patterns of HIV risk behavior between SWs and PWID. Results of this study indicate that SWs who interacted with PWID sexually have higher odds of exposure to drug injection. Thus, SWs who had sex with PWID can be expected to be at a higher risk of HIV infection due to overlapping risk exposure (i.e., the risk of injection and having sex with PWID). This overlapping risk, however, varies among KPs. HSWs in our study were more likely to be engaged in overlapping risk behavior than other SW populations. Thus, given that the HIV epidemic is driven by PWID in Pakistan, HSW might be at a higher risk of HIV transmission compared to others.

Consistent with previous work,10 we found that the pattern of interaction between SWs and PWID was heterogeneous by city and SW population. For instance, compared to Larkana where only about 1% of SWs reported having injected drugs, SWs from Multan followed by Lahore, Quetta, and Faisalabad might be at a higher risk of HIV transmission due to the higher odds of drug injection. Additionally, those SWs who do interact with PWID may have differing degrees of HIV exposure. In 2011, the overall HIV prevalence among PWID in 16 cities in Pakistan was estimated at 27.2%, but varied among cities, with the highest prevalence from Faisalabad (52.5%) followed by Karachi (42.2%), Sargodha (40.6%), Lahore (30.8%), Multan (24.9%), Sukkur (19.2%), Larkana (18.6%), and Quetta (7.1%).2,3

Structural Factors Associated With Sex Worker Risk-Taking Behaviors

An important factor associated with drug injection that was discovered in this study is the usual means through which SWs solicit or communicate with their sexual clients. It highlighted that some modes of client solicitation, though not direct risks for HIV, are along the pathway to HIV risk because of the potential association with drug injection use. SWs who operationalize through mediators (network operators, pimps), by roaming around in public places, and through referral by old clients, might be exposed to a greater risk of HIV transmission than those who operationalize by phone, due to their increased risk of drug injection. Thus, in designing intervention strategies, understanding this variation in structural factors that may drive the HIV risk is crucial. This evidence may help to design interventions that explicitly aim to target structural factors that lie along the pathways to HIV risk.

The risk of HIV acquisition varies widely, dependent on many individual factors, such as condom use,30 circumcision,31–34 antiretroviral treatment initiation by both the infected and uninfected partner,35 and use of sterilized needle and syringe during needle-sharing. Thus, accounting for all these individual factors, alongside the heterogeneous networking structure (how SWs solicit or communicate with clients) and overlapping of risks between SWs and PWID, is crucial to halt the trajectory of HIV transmission in a concentrated epidemic.

SW Interactions With PWID and HIV Prevalence

HIV prevalence among SWs, who injected drugs in the past 6 months, was much lower (1.99%) than has been shown in previous work among all PWID in this population (27.2%).1 This is likely explained partly by the lower age of SWs in our study, on average, than PWID. The minimum age in years for study eligibility was 15 among FSWs and HSWs, 13 among MSWs, and 18 among PWID. SWs in our sample who injected drugs were thus younger, on average, than all PWID. More importantly, this may be explained by the duration in practicing drug injection. SWs who had injected drugs in the past 6 months had practiced sex work for approximately 2.7 years longer, on average, than the length of time that PWID who exchanged sex for money had injected drugs. We did not ask people who were recruited into the study because of sex work how long they had injected drugs, but among those SWs who did inject drugs, the duration of exposure to HIV through drug injection could be as short as in the past 6 months compared to the average duration of drug injection among the PWID. The difference in HIV prevalence may also be explained by the frequency of injection after SWs started practicing drug injection. We do not have information among the SW population on frequency of injection, but as their recruitment into the study was based on sex work and not based on injecting, they may be more casual or less frequent injectors than the population that was specifically recruited into the study based on their injecting behavior.

We found that estimated HIV prevalence was slightly lower among those with one (2.56%) or both (2.09%) of the overlapping risks of sex with a PWID and injecting drugs, than among those with neither of the two risks (2.79%). This seemed counter-intuitive, so it was investigated. We explored whether it was possible that those with both overlapping risks may have been younger, thus having fewer years of exposure to HIV on average, than those with none or one mode of interaction with PWID. We also explored whether those with both overlapping risks may have more consistently used condoms, thus their safer condom behavior may have offset their more risky interactions with PWID. We found very minimal differences in mean age between those SWs who injected drugs and/or had had sex with a PWID, and those SWs who had not interacted with PWID. Neither did we find a significant difference in condom use at last sex with a paying client. In fact, what differences we did find in condom use were in the opposite direction – those who interacted with PWID were also less likely to use condoms (Table 2). It is possible that the disparity in HIV prevalence could be due to condom use with nonpaying clients or partners. Perhaps those with greater interaction with PWID practice safer condom behavior with their nonpaying sexual partners, than those with less interaction with PWID. It is also possible that the disparity in HIV prevalence could be explained by changes in risk-taking behavior after becoming HIV infected. The HIV-infected individuals may have had higher risks before they were HIV infected, and lowered their risk-taking after learning of their HIV status. The questions on our survey refer to drug injection and sex with a PWID during the past 6 months.

The main demographic distinction between HSWs, compared with FSWs and MSWs, is that HSWs were 4 to 5 years older than FSWs and MSWs, on average. In addition, HSWs had been practicing sex work approximately 5 to 6 years longer than FSWs and MSWs, on average. This difference in time of potential HIV exposure could explain why HIV prevalence patterns among HSW differed from those among FSWs and MSWs.

Limitations

Although data on condom use among SWs with any paying client was available, we were unable to assess specifically condom use with PWID. Also, while we were able to assess whether or not the SW had injected drugs, details of frequency and needle sharing were unavailable. This study was also limited in ability to assess underlying factors that may drive SWs to inject drugs. For instance, some SWs may offer sexual services in exchange for drugs. These SWs may have begun by injecting and moved into SW to support their injecting habit. They may differ in risk-taking exposures with those SWs who may have begun to inject drugs as a means of coping with the unpleasant aspects of their occupation. Thus, we suggest further work to better understand why SWs inject drugs and how their SW is related to drug injection. We also acknowledge that the utility of age as a determinant of overlapping HIV risk is limited due to the different age cut-off criteria used to recruit among SW groups.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a need in Pakistan, as in other areas with concentrated HIV epidemics, to closely monitor high-risk behaviors that drive the mixing patterns among KPs and underlying structural factors along the pathway to HIV risk vulnerability. HIV prevention programs that combine behavioral and structural interventions, customized to local subepidemics based on key epidemiological trends, are recommended so as to have the greatest sustained impact on reducing potential spread of HIV among KPs and to the general population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Canada–Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project (HASP) team for their efforts in mapping, data collection, specimen collection, and data entry. The authors also thank the participants who took part in the surveys for their time and participation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: FSWs = female sex workers, HSWs = hijra/transgender sex workers, IBBS = integrated biological and behavioral surveillance, KPs = key populations, MSWs = male sex workers, PWID = people who inject drugs, SWs = sex workers.

Performed the data analyses, wrote the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript: DYM; cowrote the manuscript and critically reviewed the manuscript: LAS; critically reviewed the manuscript and revised later drafts: SYS, TR, FE, and JFB; involved in the design of the study: LHT, BKA, SF, TR, FE, and JFB; all authors interpreted the results and made a substantial contribution to the final version of the article.

The Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Projected was funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA PK 30849).

The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript.

All authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.National AIDS Control Program, Pakistan. Global AIDS Response Progress Report 2014: Country progress report Pakistan. National AIDS Control Program, Ministry of National Health Services Regulation and Coordination, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad 2014. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents//PAK_narrative_report_2014.pdf (accessed January 30, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project (HASP). HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan: National report round IV, 2011. National AIDS control program, Ministry of Health, Pakistan. http://www.nacp.gov.pk/library/reports/Surveillance & Research/HIV-AIDS Surveillance Project-HASP/HIV Second Generation Surveillance in Pakistan - National report Round IV 2011.pdf (accessed January 30, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reza T, Melesse DY, Shafer LA, et al. Patterns and trends in Pakistan's heterogeneous HIV epidemic. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89 suppl 2:ii4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra S, Thompson LH, Sonia A, et al. Sexual behaviour, structural vulnerabilities and HIV prevalence among female sex workers in Pakistan. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89 suppl 2:ii34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Ambrosio M, Semini I, et al. Revitalizing the HIV response in Pakistan: a systematic review and policy implications. Int J Drug Policy 2014; 25:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Lind van Wijngaarden JW, Schunter BT, Iqbal Q. Sexual abuse, social stigma and HIV vulnerability among young feminised men in Lahore and Karachi, Pakistan. Cult Health Sex 2013; 15:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddiqui AU, Qian HZ, Altaf A, et al. Condom use during commercial sex among clients of Hijra sex workers in Karachi, Pakistan (cross-sectional study). BMJ Open 2011; 1:e000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anonymous. Pakistan combats hidden AIDS menace. AIDS Wkly Plus 1996. 16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Country Office, Pakistan. Illicit Drug Trends in Pakistan. The Paris PACT initiative: a partnership to counter trafficking and consumption of Afgan opiates. http://www.unodc.org/documents/regional/central-asia/ (accessed January 30, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archibald CP, Shaw SY, Emmanuel F, et al. Geographical and temporal variation of injection drug users in Pakistan. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89 suppl 2:ii18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson LH, Salim M, Baloch CR, et al. Heterogeneity of characteristics, structure, and dynamics of male and hijra sex workers in selected cities of Pakistan. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89 suppl 2:ii43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/Global_report.htm (accessed January 15, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project (HASP). HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan: National report round III, 2008. National AIDS control program, Ministry of Health, Pakistan. http://www.nacp.gov.pk/library/reports/Surveillance & Research/HIV-AIDS Surveillance Project-HASP/HIV Second Generation Surveillance in Pakistan – National report Round III 2008.pdf (accessed January 30, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project (HASP). HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan: National report round II, 2006–2007. National AIDS control program, Ministry of Health, Pakistan. http://www.nacp.gov.pk/library/reports/Surveillance & Research/HIV-AIDS Surveillance Project-HASP/HIV Second Generation Surveillance in Pakistan – Round 2 Report 2006–07.pdf (accessed January 30, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project (HASP). HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan: National report round I, 2005. National AIDS control program, Ministry of Health, Pakistan. http://www.nacp.gov.pk/library/reports/Surveillance & Research/HIV-AIDS Surveillance Project-HASP/HIV Second Generation Surveillance in Pakistan - Round 1 Report - 2005.pdf (accessed January 30, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanif HM. An assessment of the Pakistan national HIV/AIDS strategy for sex workers. J Infect Public Health 2012; 5:215–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations, July 2014. Geneva, Switzerland. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128048/1/9789241507431_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed January 30, 2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmad S, Mehmood J, Awan AB, et al. Female spouses of injection drug users in Pakistan: a bridge population of the HIV epidemic? East Mediterr Health J 2011; 17:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bokhari A, Nizamani NM, Jackson DJ, et al. HIV risk in Karachi and Lahore, Pakistan: an emerging epidemic in injecting and commercial sex networks. Int J STD AIDS 2007; 18:486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.UNAIDS, ed. Redefining AIDS in Asia: Crafting an Effective Response, Report of the Commission on AIDS in Asia. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shakarishvili A, Dubovskaya LK, Zohrabyan LS, et al. Sex work, drug use, HIV infection, and spread of sexually transmitted infections in Moscow, Russian Federation. Lancet 2005; 366:57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saidel TJ, Jarlais DD, Peerapatanapokin W, et al. Potential impact of HIV among IDUs on heterosexual transmission in Asian settings: scenarios from the Asian Epidemic Model. Int J Drug Policy 2003; 14:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulsudjarit K. Drug problem in southeast and southwest Asia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004; 1025:446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poshyachinda V. Drugs and AIDS in Southeast-Asia. Forensic Sci Int 1993; 62:15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emmanuel F, Adrien A, Athar U, et al. Using surveillance data for action: lessons learnt from the second generation HIV/AIDS surveillance project in Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J 2011; 17:712–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emmanuel F, Blanchard J, Zaheer HA, et al. The HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project mapping approach: an innovative approach for mapping and size estimation for groups at a higher risk of HIV in Pakistan. AIDS 2010; 24 suppl 2:S77–S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sändal C, Swensson B. Model Assisted Survey Sampling. New York, USA: Springer-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohr SL. Sampling: Design and Analysis. 2nd edBoston, USA: Brooks/Cole; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambers R, Skinner C. Analysis of Survey Data. Chichester: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weller SC, Davis-Beaty K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 1:CD003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, et al. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med 2005; 2:e298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369:643–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byakika-Tusiime J. Circumcision and HIV infection: assessment of causality. AIDS Behav 2008; 12:835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet 2007; 369:657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]