Abstract

Drug-associated thrombocytopenia is common and curable, but there were few reports about entecavir-associated thrombocytopenia.

We report here a case of a 65-year-old female patient with decompensated cirrhosis. The patient developed a fatal thrombocytopenia while under entecavir treatment. After she received entecavir treatment for 4 days, the patient's platelet count dropped significantly to 1 × 109/L, accompanied with a manifestation of mild sclera bleeding. All diagnostic data suggested an entecavir-induced immunological thrombocytopenia. The patient eventually fully recovered after treated with daily intravenous immunoglobulin infusions.

Actually, there were only a handful of reports that children or adults with chronic hepatitis B developed a thrombocytopenia due to nucleoside analogue medication. Timeliness of intravenous immunoglobulin infusion could stop the fatal bleeding for patients with entecavir-associated immunological thrombocytopenia. Hence, early diagnosis and treatment are recommended. Our case suggested that the platelet count should be monitored regularly in patients with decompensated cirrhosis with underline immunological disease while treated with ETV.

INTRODUCTION

Long-term nucleoside analogues (NAs) are the 1st-line treatments for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and HBV-induced liver cirrhosis because of less side effects and higher tolerance than pegylated interferon alpha. Entecavir (ETV) has been proven to be effective and safe in treating CHB, especially for lamivudine (LMV)-resistant CHB patients and patients with high HBV-DNA levels.1–3 ETV works by inhibiting the polymerase activity of HBV, stopping HBV proliferation, and lowering HBV DNA level significantly.4 The reported adverse effects of ETV include headache, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, and so forth.5,6 Rare but serious adverse events were reported among patients with myopathy, lactic acidosis, and thrombocytopenia. Drug-induced immunological thrombocytopenia is one of those serious adverse events and has been reported in the CHB patients treated with various NAs.7–10 We have reviewed the literature (Table 1) regarding NAs-associated thrombocytopenia for clues on its clinical and pathologic features, management, prognosis, and prophylaxis. No report was found on thrombocytopenia caused by ETV monotherapy in decompensated cirrhotic patients. Here, we report a case of an old female patient of decompensated cirrhosis who developed a fatal thrombocytopenia after she received ETV treatment.

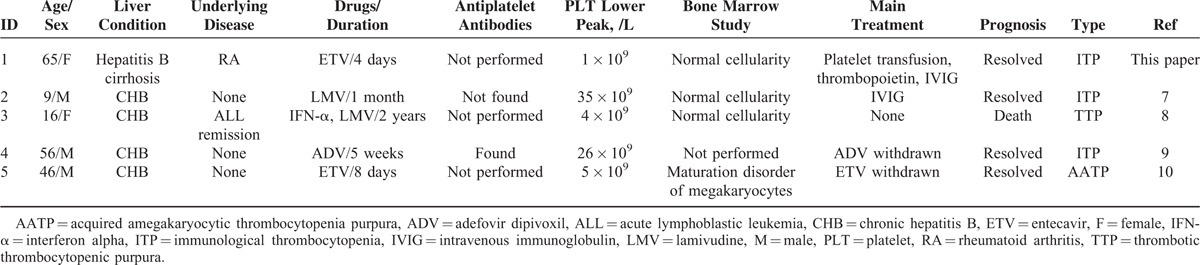

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Patients With Thrombocytopenia After Treated With Various Nucleotide Analogues

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old Han Chinese female was admitted to our hospital with symptoms of ascites and abdominal distension in April 2015. Diagnosis results on hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBeAg), and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) were positive, while antibodies to hepatitis C and delta hepatitis were absent. There was no evidence of cytomegalovirus, HIV virus, Herpes simplex virus, or Epstein–Barr virus. The detail data of serologic markers are: <5.00 AU/mL cytomegalovirus IgM, 0.285COI HIVCOM, and <10.00 AU/mL Rube-IgM. Epstein–Barr virus DNA was negative by real-time PCR assay. In addition, the diagnosis results were also negative for serologic markers of autoimmune hepatitis (AMA, LKM, LC-1, and SLA were all negative, 28.7 g/L globulin, 15.5 g/L IgG, and 669 mg/L IgM). Hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin: 96.3 μmol/L) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count: 45 × 109/L) were measured through blood examination. Meanwhile, transaminases were elevated (alanine aminotransferase: 126 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase: 302 IU/L; reference value: 0–40 IU/L). HBV-DNA in serum was more than 5.00E + 07 IU/mL. The autoimmune inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was stable as rheumatoid factor (RF) was 35.60 IU/mL before ETV treatment was initiated, and RF was less than 20.00 IU/mL when the patient came back for the follow-up examination. Although the results of anticardiolipin IgG and antiphospholipid were absent due to the high diagnosis cost, no signs or symptoms of swelling were shown in the joints when the patient was hospitalized. Other laboratory test results were unremarkable. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed signs of decompensated cirrhosis and a 4.6 cm-wide spleen.

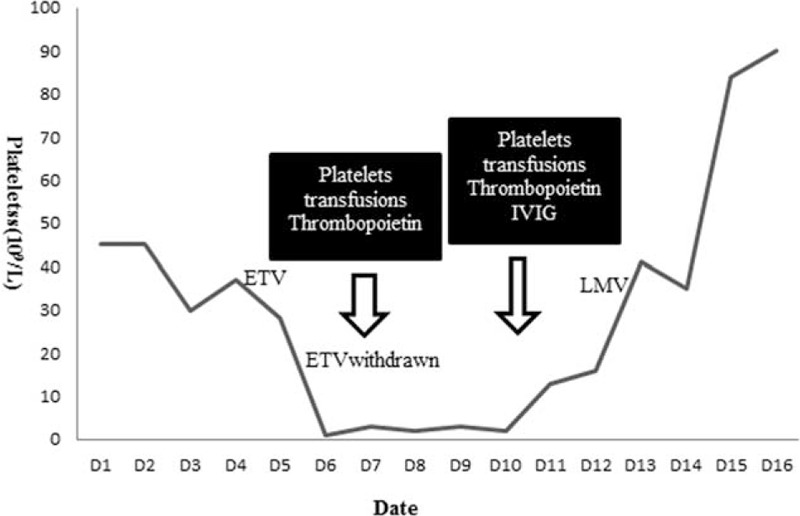

The patient had a fever above 39 °C several days before she was treated with ETV. The temperature dropped back to normal soon after the ETV treatment. As she had massive ascites, antibiotic (cefoperazone/sulbactam) was given to her once she went through the blood culture and abdominocentesis. Blood culture results (duplicate experiments) and PMN in her ascitic fluid specimen through routine analysis were negative. Blood tests showed that platelet counts were unchanged compared with the baseline during the 1st 10 days. Four days after antibiotic was administered, the platelet count remained constant. Subsequently, she began to take ETV 0.5 mg/day when she was diagnosed with high HBV-DNA level. The patient did not experience any discomfort, such as headache or nausea after the treatment started. Four days after the initiation of ETV treatment, the patient showed thrombocytopenia that dropped to 1 × 109/L, while white blood cell (WBC) and hemoglobin (HGB) stayed the same. In addition, she also experienced an intermittent nasal hemorrhage and a mild sclera bleeding in her left eye. No other evidences of new infections or sickness could be found. ETV medication was stopped immediately. Since the patient was in urgent condition, frequent platelets transfusions and thrombopoietin were applied for several days. Platelet count did not increase until she took the daily intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) of 0.4 g/(kg day) (Figure 1).11 Her clinical symptoms of sclera bleeding faded away gradually, too. The bone marrow smear showed a normal human myelogram (Figure 2). The platelet count gradually reached a relatively high value (90 × 109/L) after the 2-week treatment.

FIGURE 1.

Progression of platelet count. Thrombocytopenia took place after the 4-day treatment of ETV while other medications remained unchanged. ETV was discontinued since the patient showed a sharp thrombocytopenia. Platelets transfusion was given when the plate count declined to 1 × 109/L. Plate count did not increase meaningfully until additional 1-week of IVIG was given to her. Then the antiviral therapy was switched to LMV. ETV = entecavir, IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin, LMV = lamivudine.

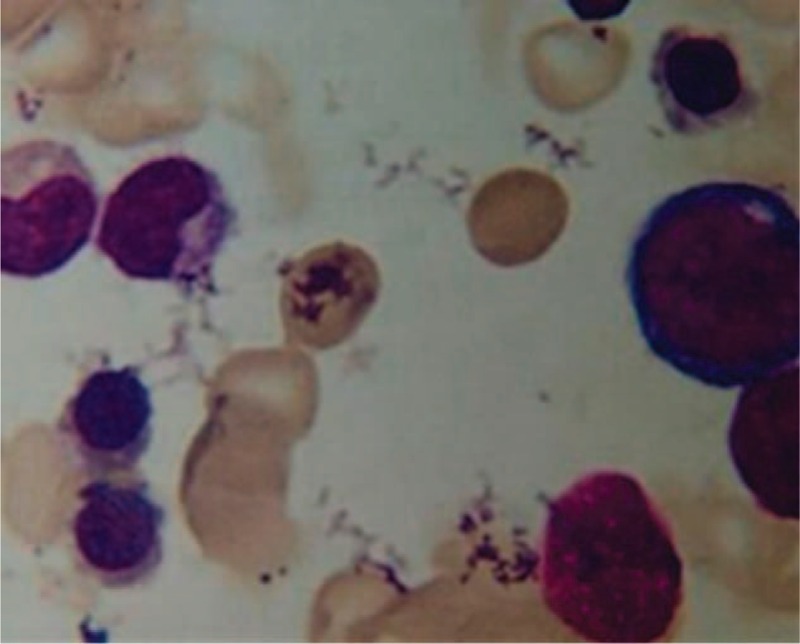

FIGURE 2.

Marrow smear prior to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). It presented an active proliferation of bone marrow cells.

The platelet count came down to 35 × 109/L 10 days after she was discharged, but it did not cause any similar symptom even after the cessation of IVIG for a long time.

DISCUSSION

ETV has been an important agent as the 1st-line treatment of CHB in patients with decompensated liver disease. In this case, the patient had taken oral methotrexate and aceclofenac for 20 years, since she was diagnosed of rheumatoid arthritis. Although it was reported that immune dysfunction could result in thrombocytopenia, the patient's autoimmune inflammation was stable and her immunosuppressive therapy was discontinued 2 months ago.12 In addition, the platelet count remained stable before the ETV treatment. Therefore, these symptoms ruled out methotrexate-induced acute thrombocytopenia.

The patient did have a fever over 39 °C before she was treated with ETV. Physical examination showed symptoms and signs of intraabdominal infection. Antibiotics (cefoperazone/sulbactam) were applied after blood culture and abdominocentesis were performed. Although thrombocytopenia might be associated with 3% of patients on cefoperazone/sulbactam treatment,13 the infection took place and antibiotic was taken several days before she was treated with ETV. She continued taking antibiotics even 1 week after she finished the IVIG treatment. Therefore, we believed that the existing infection and antibiotics might not be responsible for her thrombocytopenia. Since the platelet count did not decrease until the ETV treatment started, this sharp thrombocytopenia was highly caused by ETV.

According to the massive efficacy and safety data from previous clinic trials, CHB or decompensated cirrhosis was not coupled with other diseases. We believed that this fatal thrombocytopenia only happened to decompensated cirrhotic patients coupled with rheumatoid arthritis after they were treated with ETV.

Thrombocytopenia in peripheral blood is common in cirrhotic patients, mostly caused by hypersplenism or myelosuppression due to long-term CHB infection.14 Although this patient did have thrombocytopenia before the ETV treatment, the platelet count was measured constantly with values ranging from 40 × 109 to 50 × 109/L. The platelet count declined sharply to 1 × 109/L after a 4-day ETV treatment, and it did not increase until the patient took the IVIG treatment. Therefore, it is highly likely that this thrombocytopenia was immunological, with platelets in peripheral blood destructed by platelet antibodies. This hypothesis could explain how ETV could result in sharp thrombocytopenia in our patient.15 As far as we know, this is the first reported case that an old female patient of hepatitis B cirrhosis and RA suffered from a fatal thrombocytopenia after she received ETV treatment. Kim et al15 did report that ETV might enhance cytokine release and immune-mediated responses. Further work will be conducted to understand the mechanism for such as rare case.

For a more comprehensive understanding of the clinical features of NAs-induced thrombocytopenia, in the next section, a short review of NAs-induced thrombocytopenia was presented7–10 (Table 1). Several characteristics of NAs-induced thrombocytopenia were identified: most cases were immunological, while only 1 case showed a thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and the other one belonged to acquired amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia purpura. Reports of thrombocytopenia caused by ETV monotherapy were rare, and this paper analyzed problems in ETV-induced immunological thrombocytopenia. For this patient, we believed that ETV might interact with RA-associated immune dysfunction, while the pathogenesis remained unknown and more research is needed. A longer term observation is warranted for further demonstration.

CONCLUSION

Although sometimes it is difficult to distinguish drug-associated immunological thrombocytopenia from decreased platelet production,16 careful analysis of all clinical history and a marrow biopsy could help on the diagnosis of drug-induced immunological thrombocytopenia. Based on this case, if a fatal thrombocytopenia develops following the medications and routine treatment cannot relieve the symptom, IVIG treatment is highly recommended. Our case also suggested that the platelet count should be monitored regularly in patients with decompensated cirrhosis with underline immunological disease while they are treated with ETV.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank their colleagues and the devotion of the patient.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AATP = acquired amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia purpura, ADV = adefovir dipivoxil, ALL = acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AMA = anti-mitochondrial antibodies, CHB = chronic hepatitis B, CT = computed tomography, ETV = entecavir, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HGB = hemoglobin, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, IFN-α = interferon alpha, ITP = immunological thrombocytopenia, IVIG = intravenous immunoglobulin, LC-1 = liver cytosol antigen type I, LKM = liver kidney microsomal antibodies, LMV = lamivudine, NA = nucleoside analogue, PLT = platelet, PMN = polymorphonuclea, RA = rheumatoid arthritis, RF = rheumatoid factor, SLA = soluble liver antigen, TTP = thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, WBC = white blood cell.

Xiaoli Fan and Liyu Chen contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ye XG, Su QM. Effects of entecavir and lamivudine for hepatitis B decompensated cirrhosis: meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:6665–6678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shim JH, Lee HC, Kim KM, et al. Efficacy of entecavir in treatment-naive patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2010; 52:176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvaruso V, Craxi A. Regression of fibrosis after HBV antiviral therapy. Is cirrhosis reversible? Liver Int 2014; 34 suppl 1:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai CL, Rosmawati M, Lao J, et al. Entecavir is superior to lamivudine in reducing hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Gastroenterology 2002; 123:1831–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manns MP, Akarca US, Chang TT, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B in the rollover study ETV-901. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2012; 11:361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Liu L, Zhang M, et al. The efficacy and safety of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B-associated liver failure: a meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol 2015; 14:150–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebensztejn DM, Kaczmarski M. Lamivudine-associated thrombocytopenia. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2687–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selimoglu MA, Ertekin V, Kiki I, et al. Lamivudine and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: cause or coincidence. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005; 39:82–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stornaiuolo G, Amato A, Gaeta GB. Adefovir dipivoxil-associated thrombocytopenia in a patient with chronic hepatitis B. Dig Liver Dis 2006; 38:211–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li BMLJ. Entecavir-associated thrombocytopenic purpura: a case report. Chin Commun Doctors 2009; 24:232–233. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooper JA. Intravenous immunoglobulins: evolution of commercial IVIG preparations. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2008; 28:765–778.viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colebatch AN, Marks JL, Edwards CJ. Safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including aspirin and paracetamol (acetaminophen) in people receiving methotrexate for inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, other spondyloarthritis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; Cd008872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jauregui LE, Appelbaum PC, Fabian TC, et al. A randomized clinical study of cefoperazone and sulbactam versus gentamicin and clindamycin in the treatment of intra-abdominal infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 1990; 25:423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi H, Beppu T, Shirabe K, et al. Management of thrombocytopenia due to liver cirrhosis: a review. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:2595–2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JT, Jeong HW, Choi KH, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reaction resulting in maculopapular-type eruption due to entecavir in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:15931–15936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George JN, Aster RH. Drug-induced thrombocytopenia: pathogenesis, evaluation, and management. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2009; 153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]