Abstract

The purpose of this report is to present a case of myeloid sarcoma of the gingiva with myelodysplastic syndrome.

A 52-year-old male diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome with skin lesions presented with gingival swelling and gingival redness involving the maxillary left second premolar and the maxillary left first molar. The patient was referred from the Department of Hematology for a biopsy of the lesion. Full-thickness flaps were elevated and inflamed, and neoplastic soft tissue was removed from a lesion and the samples sent for histopathologic analysis.

Histopathologic results showed leukemic cell infiltration beneath the oral epithelium, and the specimen was positive for the leukocyte marker. The diagnosis was myeloid sarcoma. Uneventful healing was observed at 2-week follow-up, but relapse of the lesions with the hyperplastic and neoplastic tissue was noted at 4-week follow-up. Further follow-up or treatment could not be performed because the patient did not visit at the next follow-up.

In conclusion, myeloid sarcoma should be a diagnosis option for gingival growth because it can involve intraoral lesion. In this report, a biopsy was performed due to referral considering the patient's medical history. Although myeloid sarcoma in the oral cavity is extremely rare, a small biopsy and consultation with a hematologist may be beneficial for patients and may provide a differential diagnosis.

Keywords: biopsy, case report, differential diagnosis, gingiva, myeolid sarcoma, myelodysplastic syndromes

1. Introduction

Myeloid sarcoma (previously known as granulocytic sarcoma or chloroma) is an uncommon extramedullary tumor composed of dense aggregates of immature myeloid precursor cells.[1] Infiltrations of any site of the body by myeloid precursor cells in leukemic patients are not classified as myeloid sarcoma unless they present tumor masses in which the tissue architecture effaced.[2]

Myeloid sarcoma was reported in only 3% to 9% of patients with myeloid leukemia, and 60% of patients with myeloid sarcoma are <15 years of age.[3] Although myeloid sarcoma can affect almost every site of the body, it has been reported more often in the skin, bone, and lymph node.[4,5] The involvement of multiple myeloid sarcoma sites is found in <10% of cases.[4,5] Myeloid sarcoma may develop de novo or concurrently with acute myeloid leukemia, myeloproliferative neoplasm, or myelodysplastic syndrome.

The purpose of this report is to present a case of myeloid sarcoma of the gingiva with myelodysplastic syndrome. Intraoral occurrence of myeloid sarcoma is extremely rare.[6] Although several myeoloid sarcoma of the oral cavity were reported previously,[1,6–14] 2-site involvement, including gingiva and skin, may be a rare case.

2. Ethics, consent, and permissions

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea (KC14ZISE0338).

3. Case presentation

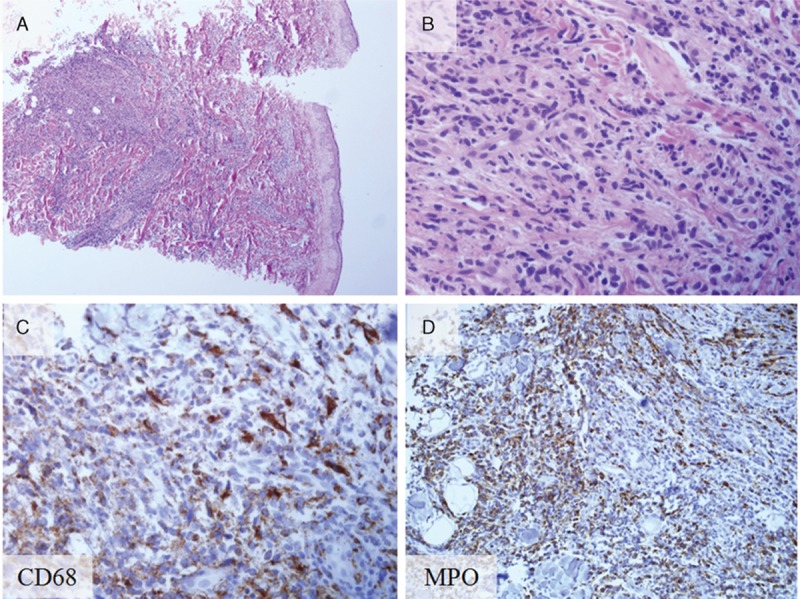

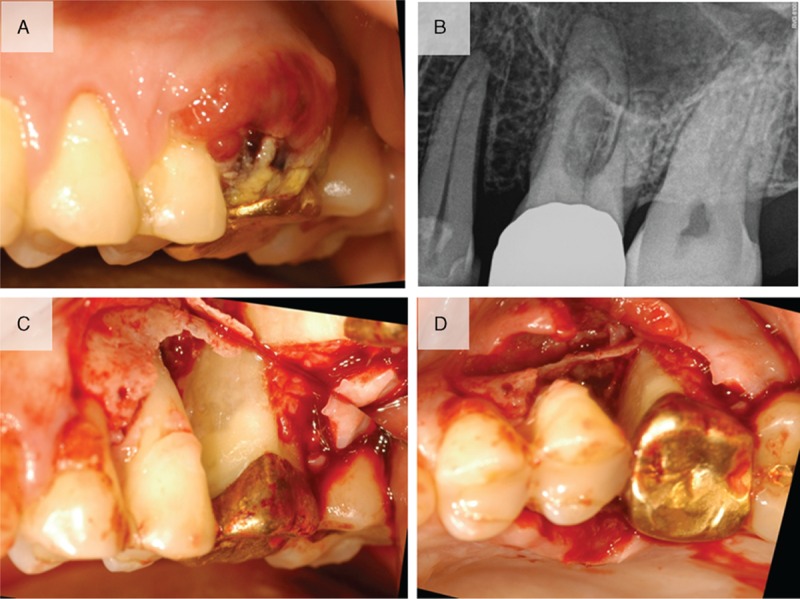

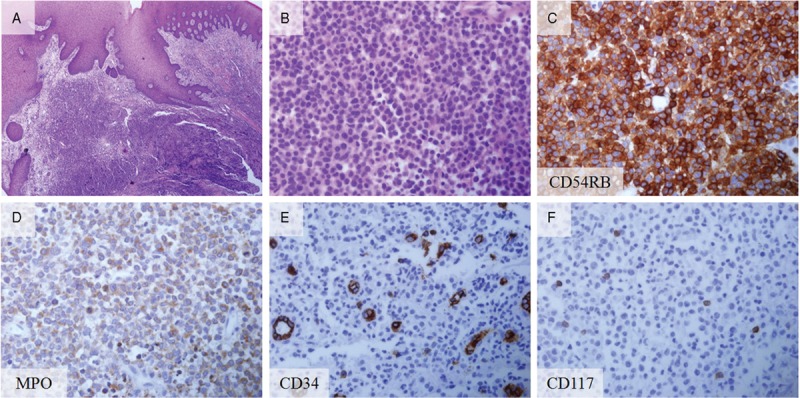

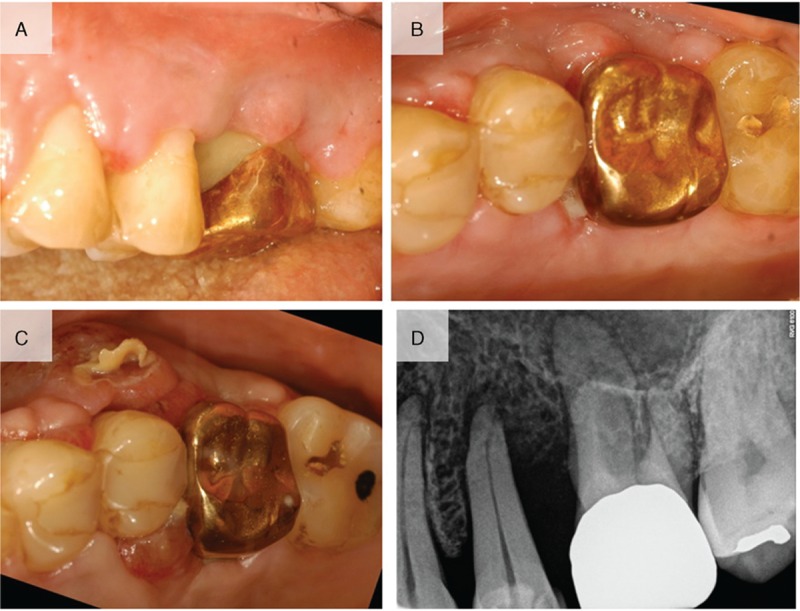

The 52-year-old male patient was previously diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome at another hospital. A hematologic test showed that the patient was suspected of conversion to acute myeloid leukemia. Closer examination showed that the patient was suspected of refractory anemia with excess blasts-1 or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Multiple skin-colored or bluish masses were presented on the trunk for 10 days. Skin biopsy and histologic sections showed perivascular and diffuse infiltration of atypical mononuclear cells in the mid and deep dermis (Fig. 1A and B). On immunohistochemical staining, the tumor cells were positive for CD68 (Fig. 1C) and myeloperoxidase (Fig. 1D). Histopathological findings were compatible with leukemia cutis. The patient was referred from the Department of Hematology to the Department of Periodontics for the biopsy of the lesion to evaluate the leukemic infiltration after visiting the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. The patient's chief complaint was swelling of the maxillary left gingiva. Oral examination revealed gingival swelling with gingival redness involving the maxillary left second premolar and the maxillary left first molar (Fig. 2A). The deepest probing depth was 12 mm at the maxillary left second premolar and the maxillary left first molar interdental area. In periapical radiograph, the widening of periodontal ligament space was observed at the maxillary left second premolar (Fig. 2B). There was consultation with the Department of Hematology for the possibilities and considerations of the flap operation and an extraction was made. Full-thickness flaps were elevated and inflamed and neoplastic soft tissues were removed from lesion (Fig. 2C and D). The samples were sent to the Department of Pathology for histopathologic analysis. Hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections revealed mass formation with atypical mononuclear cells beneath the oral epithelium (Fig. 3A and B). The tumor cells were positive for leukocyte common antigen CD45RB (Fig. 3C) and myeloperoxidase (Fig. 3D). In addition, some scattered cells were positive for CD34 and CD117 (Fig. 3E and F). The histopathological findings were compatible with myeloid leukemic infiltration of myeloid sarcoma. Uneventful healing was observed at 2-week follow-up (Fig. 4A and B). At the 4-week follow-up, relapse of the lesions with the hyperplastic and neoplastic tissue was noted (Fig. 4C). Periapical radiograph showed bone loss at the interdental area between the maxillary left second premolar and the maxillary left first molar (Fig. 4D). Extraction of the maxillary left second premolar was planned, but the patient did not visit at the next follow-up.

Figure 1.

Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining of biopsy from the skin leukemia cutis. (A) Leukemic cell infiltration beneath the epidermis (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×40). (B) Magnified view of the leukemic cell infiltration (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×400). (C) CD68-positive cells (CD68 staining; original magnification ×400). (D) Myeloperoxidase-positive (MPO) cells (MPO staining; original magnification ×400). MPO cells = myeloperoxidase-positive cells.

Figure 2.

Clinical view and radiograph at the first visit. (A) Clinical view indicating gingival swelling with gingival redness involving the maxillary left second premolar and the maxillary left first molar. (B) Periapical radiograph indicating the widening of periodontal ligament space at the maxillary left second premolar. (C) Buccal view showing the removal of inflamed or neoplastic soft tissues. (D) Occlusal view after removal of the tissues.

Figure 3.

Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining of biopsy from the gingiva. (A) Leukemic cell infiltration beneath the oral epithelium (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×40). (B) Magnified view showing the leukemic cell infiltration (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×400). (C) Leukocyte marker (CD45RB)-positive (CD45RB staining; original magnification ×400). (D) MPO-positive cells (MPO staining; original magnification ×400). (E) Some cells were positive for CD34 (CD 34 staining; original magnification ×400). (F) Number of cells were CD117 positive (CD117 staining; original magnification ×400). MPO cells, myeloperoxidase-positive cells.

Figure 4.

(A) Clinical photograph at 2 weeks after surgery showing uneventful healing. (B) Occlusal view at 2 weeks after surgery. (C) Relapse of the lesions in the hyperplastic and neoplastic tissue was noted 4 weeks after the surgery. (D) Periapical radiograph showed bone loss between the maxillary left second premolar and the maxillary left first molar.

4. Discussion

Myeloid sarcoma may occur under 3 clinical settings: (1) it may precede or coincide with acute myeloid leukemia; (2) it may occur in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes or myeloproliferative neoplasm; (3) it may have initial manifestation of relapse of acute myeloid leukemia.[15] Myelodysplastic syndrome is the group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell diseases characterized by cytopenia, dysplasia in 1 or more of the major myeloid cell lines, ineffective hematopoiesis, and increased risk of development of acute myeloid leukemia.[16] In this report, therefore, the patient had the possibility of acute myeloid leukemia because of the myeloid sarcoma at 2 sites and increased risk of secondary acute myeloid leukemia in myelodysplastic syndrome patients. A previous study reported that acute myeloid leukemia occurs after 1 to 25 months in most cases of myeloid sarcoma.[17] In this report, rapid growth of tumor mass was observed 4 weeks after surgery. Several factors can be considered as the cause of relapse. Myeloid sarcoma has an invasive and aggressive character and the myeloid sarcoma-derived cell line has the type IV collagenase (matrix metalloproteinase-2 [MMP-2]).[18] Type IV collagenase has been reported to be related to poor prognosis for cancer.[19] Furthermore, myeloid sarcoma cells are the only cell line among several leukemic cell lines to bind both bone marrow stromal layers and dermal fibroblast.[20] The patient was under schedule for intensive chemotherapy and radiotherapy after the confirmation of the biopsy. The biopsy results in the Department of Dermatology and the Department of Periodontology may provide the rationale for a further treatment regimen for myeloid sarcoma, but open flap debridement performed for the biopsy may have increased the tumor growth.[21] Although there is no consensus about the treatment of myeloid sarcoma, the current recommended treatment regimen in patients presenting with isolated myeloid sarcoma or myeloid sarcoma presenting concomitantly with acute myeloid leukemia is conventional acute myeloid leukemia-type chemotherapy.[22]

In conclusion, myeloid sarcoma should be a diagnosis option for gingival growth because it can involve intraoral lesion. In this report, a biopsy was performed due to referral considering the patient's medical history. Although myeloid sarcoma in the oral cavity is extremely rare, a small biopsy and consultation with a hematologist may be beneficial for a patient and may provide a differential diagnosis.

Footnotes

Abbreviation: MMP-2 = matrix metalloproteinase-2.

Funding: this research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2014R1A1A1003106).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Antmen B, Haytac MC, Sasmaz I, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma of gingiva: an unusual case with aleukemic presentation. J Periodontol 2003;74:1514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ferri E, Minotto C, Ianniello F, et al. Maxillo-ethmoidal chloroma in acute myeloid leukaemia: case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2005;25:195–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Liu PI, Ishimaru T, McGregor DH, et al. Autopsy study of granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) in patients with myelogenous leukemia, Hiroshima-Nagasaki 1949–1969. Cancer 1973;31:948–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Falini B, Lenze D, Hasserjian R, et al. Cytoplasmic mutated nucleophosmin (NPM) defines the molecular status of a significant fraction of myeloid sarcomas. Leukemia 2007;21:1566–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pileri SA, Ascani S, Cox MC, et al. Myeloid sarcoma: clinico-pathologic, phenotypic and cytogenetic analysis of 92 adult patients. Leukemia 2007;21:340–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Matsushita K, Abe T, Takeda Y, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma of the gingiva: two case reports. Quintessence Int 2007;38:817–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Eisenberg E, Peters ES, Krutchkoff DJ. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) of the gingiva: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991;49:1346–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee SS, Kim HK, Choi SC, Lee JI. Granulocytic sarcoma occurring in the maxillary gingiva demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;92:689–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yinjun L, Jie J, Zhimei C. Granulocytic sarcoma of the gingiva with trisomy 21. Am J Hematol 2006;81:79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Niscola P, Tendas A, Scaramucci L, et al. Gingival myeloid sarcoma in myelodysplastic syndrome. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:917–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Papamanthos MK, Kolokotronis AE, Skulakis HE, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia diagnosed by intra-oral myeloid sarcoma. A case report. Head Neck Pathol 2010;4:132–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Guastafierro S, Falcone U, Colella G. Gingival swelling and pleural effusion: non-leukemic myeloid sarcoma. Eur J Haematol 2013;91:94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stoopler ET, Pinto A, Alawi F, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma: an atypical presentation in the oral cavity. Spec Care Dentist 2004;24:65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yoon AJ, Pulse C, Cohen LD, et al. Myeloid sarcoma occurring concurrently with drug-induced gingival enlargement. J Periodontol 2006;77:119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Neiman RS, Barcos M, Berard C, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases. Cancer 1981;48:1426–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Swerdllow S, Campo E, Harris NL. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. France: IARC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Byrd JC, Edenfield WJ, Shields DJ, et al. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: a clinical review. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:1800–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kobayashi M, Hamada J, Li YQ, et al. A possible role of 92 kDa type IV collagenase in the extramedullary tumor formation in leukemia. Jpn J Cancer Res 1995;86:298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shen W, Xi H, Wei B, et al. The prognostic role of matrix metalloproteinase 2 in gastric cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014;140:1003–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kobayashi M, Imamura M, Soga R, et al. Establishment of a novel granulocytic sarcoma cell line which can adhere to dermal fibroblasts from a patient with granulocytic sarcoma in dermal tissues and myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol 1992;82:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gunduz N, Fisher B, Saffer EA. Effect of surgical removal on the growth and kinetics of residual tumor. Cancer Res 1979;39:3861–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Avni B, Koren-Michowitz M. Myeloid sarcoma: current approach and therapeutic options. Ther Adv Hematol 2011;2:309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]