Abstract

Growing teratoma syndrome (GTS) is a rare clinical entity first described by Logothetis et al in 1982. Although it is unusual for GTS to be located in the ovary, this report is of a case of an adolescent girl who underwent a complete surgical resection of the mass. Histopathology confirmed only an immature teratoma had originated from the ovary and so she received adjuvant chemotherapy with blemycin, etopside, and cisplatin over 4 cycles. Results from an abdominal enhanced CT (computed tomography) 9 years later revealed a giant mass had compressed adjacent tissues and organs. Laparotomy was performed and a postoperative histopathology showed the presence of a mature teratoma, and so the diagnosis of ovarian GTS was made. One hundred one cases of ovarian GTS from English literature published between 1977 and 2015 were collected and respectively analyzed in large samples for the first time.

The median age of diagnosis with primary immature teratoma was 22 years (range 4–48 years, n = 56). GTS originating from the right ovary accounted for 57% (27/47, n = 47) whereas the left contained 43% (20/47, n = 47). Median primary tumor size was 18.7 cm (range 6–45 cm, n = 28) and median subsequent tumor size was 8.6 cm (range 1–25 cm, n = 25). From the primary treatment to the diagnosis of ovarian GTS, median tumor growth speed was 0.94 cm/month (range 0.3–4.3 cm/month, n = 21). Median time interval was 26.6 months (range 1–264 months, n = 41). According to these findings, 5 patients did have a pregnancy during the time interval between primary disease and GTS, making our patient the first case of having a pregnancy following the diagnosis of ovarian GTS. Because of its high recurrence and insensitiveness to chemotherapy, complete surgical resection is the preferred treatment and fertility-sparing surgery should be considered for women of child-bearing age.

Anyhow GTS of the ovary has an excellent prognosis. Patients with GTS had no evidence of recurrence or were found to be disease free during a 40.3-month (range 1–216 months, n = 48) median follow-up. Moreover, regular follow-ups with imaging and serum tumor markers are important and must not be neglected.

INTRODUCTION

The growing teratoma syndrome (GTS) was originally defined by Logothetis et al in 1982 as the phenomenon of subsequent growth of a benign tumor, following the removal of a primary malignant tumor during or after chemotherapy.1 Growing teratoma syndrome (GTS) is a rare entity related to both testicular and ovarian carcinoma. The incidence of GTS in a nonseminomatous germ cell of the testis is 1.9% to 7.6%, while it has been reported to occur in 12% of ovarian germ cell tumors.2,3 Generally speaking, ovarian GTS typically occurs in young adults and adolescents.4 Some researchers have recommended 3 criteria according to the Logothetis definition. The criteria of GTS includes (1) normalization of serum tumor markers, alpha fetoprotein (AFP), and human chorionic gonadotropin; (2) enlarging or new masses despite appropriate chemotherapy for nonseminomatous germ cell tumors; (3) the exclusive presence of mature teratoma in the resected specimen.5 Herein, we report a rare case of an adolescent girl with ovarian GTS, and 101 cases of ovarian GTS from English literature published between 1977 and 2015 were collected and respectively analyzed in large samples for the first time. This contributed to the understanding of the clinical features of this disease.

CASE REPORT

A 16-year-old girl was presented in August 2005 with intermittent abdominal pain and distention for half a year. Ultrasonography revealed a right ovarian tumor that occupied the whole right upper abdominal cavity. She received the right oophorectomy and the giant tumor was completely resected, showing about a 40 cm × 25 cm × 15 cm mass with intact capsule. Histopathology revealed skin, cartilage, and a malignant immature teratoma. After surgery, she was treated with 4 cycles of blemycin, etopside, and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy but refused any further treatment and missed her follow-up. In the following years, she had not felt any discomfort until August 2014. A mass in the whole right abdomen could be touched about 30 cm × 20 cm, without a clear boundary between surrounding tissues. Abdominal-enhanced CT revealed a giant mass in the retroperitoneum that compressed the postcava, the right hepatic vein, liver, pancreas, and the right kidney. Because of the compression, the portal vein, right renal artery, superior mesenteric artery, and celiac trunk had shifted to the left (Figure 1). Tumor markers, AFP, and human chorionic gonadotropin were normal while the carbohydrate antigen 125 level was 412.30 u/mL (normal, 0–35.00 u/mL), and carbohydrate antigen 199 level was over 7000 u/mL (normal, 0–37.00 u/mL). The rest of the laboratory tests were found to be negative. After a discussion by the departments of general surgery, obstetrics gynecology and urology, the patient underwent a resection of abdominal and pelvic lesions, around the liver and spleen. The giant tumor was completely resected and gross examination revealed a giant mass (29 cm × 24 cm × 12 cm) containing lipid, hair, gelatinous material, and a few nodules (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed only a mature teratoma (Figure 3). Hence, a final diagnosis of “growing teratoma syndrome (GTS)” was made. During the 14-month follow-up, no evidence of recurrence or metastasis was observed and she became pregnant 2 months after her last follow-up.

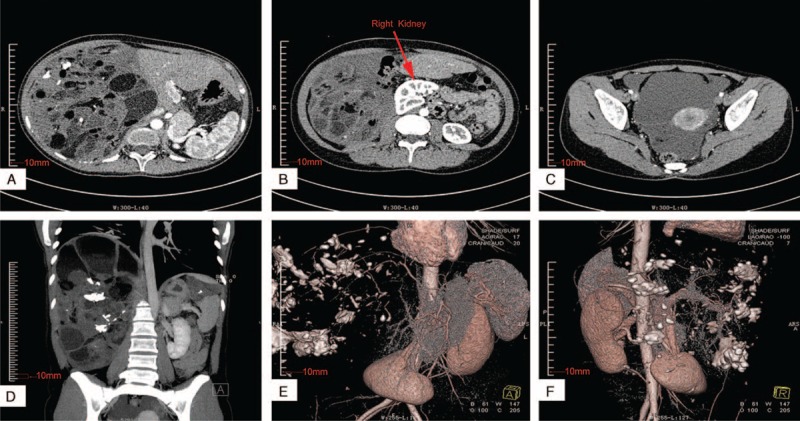

FIGURE 1.

CT showed the mass occupying the right upper abdominal cavity, revealing multiple new masses containing cystic and necrotic elements surrounding the liver (A, D, E). Because of tumor compression, the giant mass had compressed the postcava, liver, pancreas, and the right kidney (B, C). The portal vein, right renal artery, superior mesenteric artery, and celiac trunk shifted to the left and was not invaded by the tumor through the technique of 3-dimensional CT image reconstruction (D, E, F). CT = computed tomography.

FIGURE 2.

The whole abdominal lesion reached 29 cm × 24 cm × 12 cm in size (A, the ruler is 20 cm long), 5.015 kg in weight (C). A part of pelvic lesions, lesions in the hepatic envelop, and around the spleen (B).

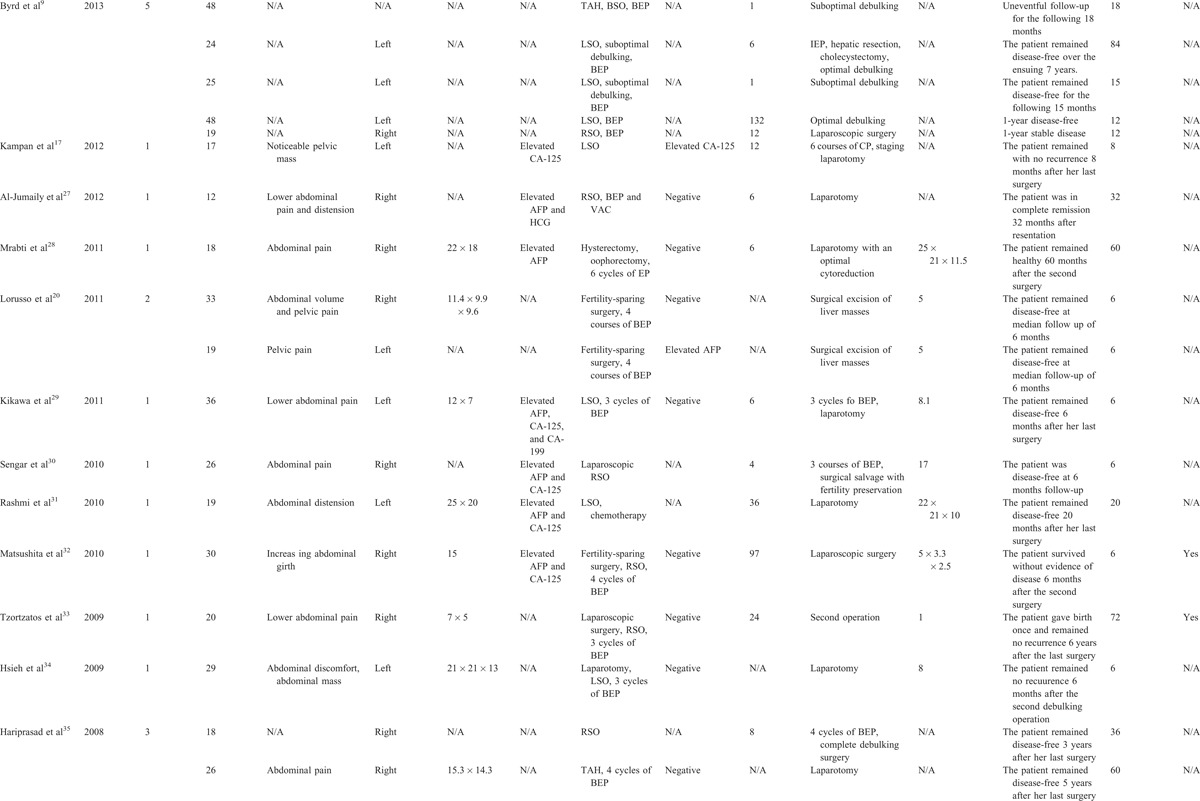

FIGURE 3.

Histopathology of mature teratoma of the abdomen cavity at the age of 24. The carcinoids are distributed in various mature tissues derived from 3 germ cell layers (HE × 100). (A) sebaceous gland (red arrow); (B) muscular tissue (red arrow); (C) bronchus tissue (red arrow). HE = hematoxylin-eosin.

DISCUSSION

This is an unusual case in which there were increasing masses 9 years after chemotherapy for an ovarian immature teratoma, but all the masses subsequently resected were shown to contain only mature teratoma. In 1977, DiSaia firstly reported 3 cases of “chemotherapeutic retroconversion” in which benign distant metastasis appeared following adjuvant chemotherapy for immature teratoma of the ovary.6 However, the term GTS was originally defined by Logothetis in 1982, when he described 6 patients with nonseminomatous germ cell tumors who subsequently developed growing metastatic masses despite appropriate systemic chemotherapy and normal range of serum tumor markers.7 The histopathology revealed benign mature teratoma without viable germ cell elements.1

GTS is characterized by an increase in metastatic mass after complete eradication of a primary malignant ovarian germ cell tumor and by normalization of serum tumor markers, either during or after chemotherapy.8,9 Some researchers considered that these 2 characters are in fact the same entity.7,8 There are 2 major inferences of GTS formation. The first hypothesis is that chemotherapy transforms malignant cells into “benign” teratomatous elements. The second hypothesis is that chemotherapy can only destroy malignant cells leaving chemoresistant teratoma behind.3,10 It remains, that there is much uncertainty around GTS due to the limited number of cases, and that either of the inference is in fact possible or that both can play an important roles in the development of GTS.

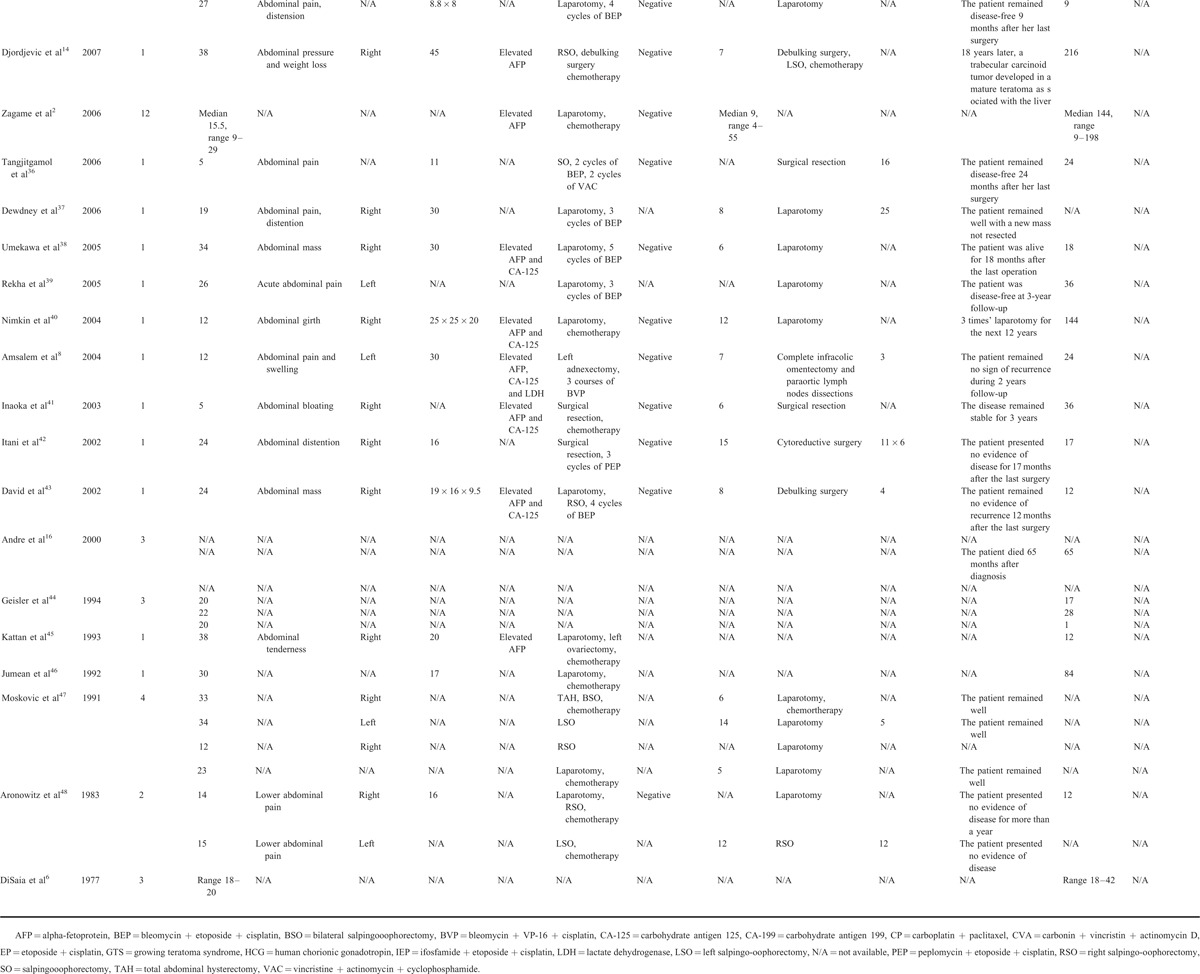

To the best of our knowledge, ovarian GTS is only 101 cases in published English literatures (Table 1 ). Most of the patients had abdominal symptoms, such as abdominal pain and distension when they first sought medical advice. In our study, the median age of the diagnosis of primary immature teratoma was 22 years (range 4–48 years, n = 56) (Table 1 ). While Bentivegna et al5 reported the median age at diagnosis was 26 years (range 8–41 years, n = 38). Because of the existence of 10 gliomatosis peritonei cases in 38, this data would not be suitable for pure GTS. GTS originating from the right ovary accounted for 57% (27/47, n = 47) and the left contained 43% (20/47, n = 47) (Table 1 ). Median primary tumor size was 18.7 cm (range 6–45 cm, n = 28) and median subsequent tumor size was 8.6 cm (range 1–25 cm, n = 25) (Table 1 ). Growing teratomas have a rapid expansion rate, with a median linear growth of 0.5 to 0.7 cm/month and volume increase of 9.2 to 12.9 cm3/month.11,12 While from the results of our study, the tumor growth was 0.94 cm/month (range 0.3–4.3 cm/month, n = 21) (Table 1 ). The discrepancy could be explained by different sample sizes.

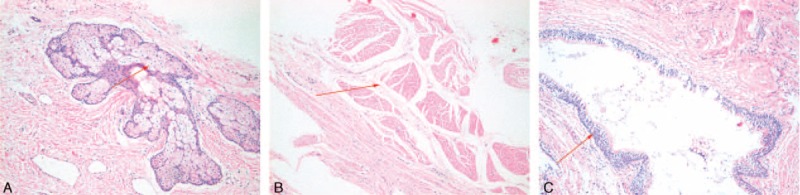

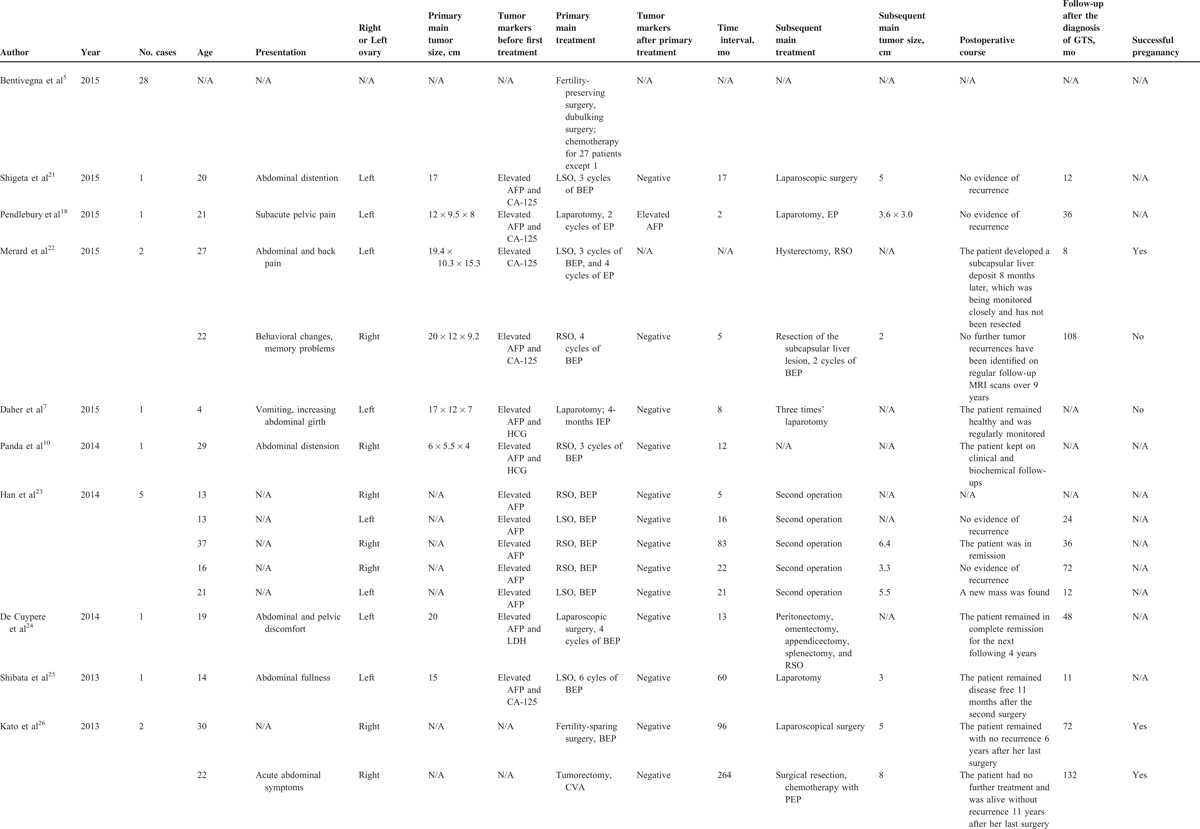

TABLE 1.

Growing teratoma syndrome of ovary

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Growing teratoma syndrome of ovary

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Growing teratoma syndrome of ovary

This behavior is unpredictable because of aggressive local spread as well as GTS having the potential for malignant degeneration.11,13,14 The GTS nodules can appear at any stage during or after chemotherapy, and in some cases can be delayed anything up to 8 years, with an average interval of 8 months.5,7,14 In our study, median time interval was 26.6 months (range 1–264 months, n = 41) (Table 1 ) and our patient was delayed up to 9 years. Therefore regular follow-ups contributed to early detection, diagnosis, and treatment. It is reported that the retroperitoneum is the most common site for GTS, followed closely by the lung, cervical lymph nodes, and mediastinum.7,15 To date, there is no reliable indicator for GTS. Close attention should always be paid to an enlarged tumor and/or normalization of serum tumor markers during chemotherapy.16–18

The preferred treatment is complete surgical resection, because of GTS having a high recurrence rate of 72% to 83% in patients with partial resection, against 0% to 4% in those who undergo complete resections, as teratomas are resistant to chemotherapy and radiation therapy.11 Early detection and reasonable complete resection of the primary lesion and implantation or metastasis are essential. Adjuvant chemotherapy with blemycin, etopside, and cisplatin was recommended for patients when diagnosed with immature teratoma following primary surgery. Palbociclib (PD0332991) is reported that it can stabilize the vascularization of the tumor in pediatric patients with an intracranial teratoma.19 But further investigation of the use of Palbociclib in patients with growing teratoma syndrome should be carried out.19 From these literatures, tumor markers AFP usually returned to within the normal range, with the exception of 2 cases reported by Pendlebury et al and Lorusso et al.18,20

So far, no standardized management protocol has been established to diagnose and treat GTS.5 However it has shown, GTS has an overall good prognosis with a 5-year overall survival rate of 89% in patients who undergo surgery.3,7 This study has shown, patients with GTS had little or no evidence of recurrence or indeed were disease free for 40.3 months (range 1–216 months, n = 48) median follow-up (Table 1 ). According to our study, 5 patients had a pregnancy during the time interval between primary disease and GTS, with our patient being the first case of having a pregnancy following the diagnosis of ovarian GTS. Therefore fertility-sparing surgery is recommended for women of child-bearing age if conditions allow. Until now, the mechanism of GTS is still unclear and the diagnosis of it has proven difficult. Consequently, the accumulation of additional data from more cases would be necessary to further elucidate this type of tumor and standardize optimal therapy.

PATIENT CONSENT

Patient consent was obtained for this study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AFP = alpha fetoprotein, BEP = blemycin etopside and cisplatin, CA = carbohydrate antigen, CT = computed tomography, GP = gliomatosis peritonei, GTS = growing teratoma syndrome, HCG = human chorionic gonadotropin, HE = hematoxylin-eosin, NSGCT = nonseminomatous germ cell of the testis.

Song Li and Zhenzhen Liu contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The study was supported by clinical capability construction project for liaoning provincial hospitals(LNCCC-B03-2014) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471755, 81272368). We really appreciate it if you could help us to add our Chinese funding.

Funding: The study was supported by clinical capability construction project for liaoning provincial hospitals(LNCCC-B03-2014) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471755, 81272368).

REFERENCES

- 1.Logothetis CJ, Samuels ML, Trindade A, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome. Cancer 1982; 50:1629–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zagame L, Pautier P, Duvillard P, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome after ovarian germ cell tumors. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108:509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorbatiy V, Spiess PE, Pisters LL. The growing teratoma syndrome: current review of the literature. Indian J Urol 2009; 25:186–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai CH, Chang TC, Hsueh S, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in ovarian germ cell malignancies. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 96:784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentivegna E, Azais H, Uzan C, et al. Surgical outcomes after debulking surgery for intraabdominal ovarian growing teratoma syndrome: analysis of 38 cases. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22 suppl 3:964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiSaia PJ, Saltz A, Kagan AR, et al. Chemotherapeutic retroconversion of immature teratoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol 1977; 49:346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daher P, Riachy E, Khoury A, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome: first case report in a 4-year-old girl. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2015; 28:e5–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amsalem H, Nadjari M, Prus D, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome vs chemotherapeutic retroconversion: case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 92:357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrd K, Stany MP, Herbold NC, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome: brief communication and algorithm for management. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2013; 53:318–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panda A, Kandasamy D, Sh C, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome of ovary: avoiding a misdiagnosis of tumour recurrence. J Clin Diagnos Res 2014; 8:197–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiess PE, Kassouf W, Brown GA, et al. Surgical management of growing teratoma syndrome: the M. D. Anderson cancer center experience. J Urol 2007; 177:1330–1334.discussion 1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DJ, Djaladat H, Tadros NN, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome: clinical and radiographic characteristics. Int J Urol 2014; 21:905–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scavuzzo A, Santana Rios ZA, Noveron NR, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome. Case Rep Urol 2014; 2014:139425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djordjevic B, Euscher ED, Malpica A. Growing teratoma syndrome of the ovary: review of literature and first report of a carcinoid tumor arising in a growing teratoma of the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol 2007; 31:1913–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denaro L, Pluchinotta F, Faggin R, et al. What's growing on? The growing teratoma syndrome. Acta neurochirurgica 2010; 152:1943–1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andre F, Fizazi K, Culine S, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome: results of therapy and long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Eur J Cancer 2000; 36:1389–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kampan N, Irianta T, Djuana A, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome: a rare case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2012; 2012:134032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pendlebury A, Rischin D, Ireland-Jenkin K, et al. Ovarian growing teratoma syndrome with spuriously elevated alpha-fetoprotein. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:e99–e100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultz KA, Petronio J, Bendel A, et al. PD0332991 (Palbociclib) for treatment of pediatric intracranial growing teratoma syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015; 62:1072–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorusso D, Malaguti P, Trivellizzi IN, et al. Unusual liver locations of growing teratoma syndrome in ovarian malignant germ cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep 2011; 1:24–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shigeta N, Kobayashi E, Sawada K, et al. Laparoscopic excisional surgery for growing teratoma syndrome of the ovary: case report and literature review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2015; 22:668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merard R, Ganesan, Hirschowitz L. Growing teratoma syndrome: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2015; 34:465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han NY, Sung DJ, Park BJ, et al. Imaging features of growing teratoma syndrome following a malignant ovarian germ cell tumor. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2014; 38:551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Cuypere M, Martinez A, Kridelka F, et al. Disseminated ovarian growing teratoma syndrome: a case-report highlighting surgical safety issues. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2014; 250–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shibata K, Kajiyama H, Kikkawa F. Growing teratoma syndrome of the ovary showing three patterns of metastasis: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2013; 6:544–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato N, Uchigasaki S, Fukase M. How does secondary neoplasm arise from mature teratomas in growing teratoma syndrome of the ovary? A report of two cases. Pathol Int 2013; 63:607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Jumaily U, Al-Hussaini M, Ajlouni F, et al. Ovarian germ cell tumors with rhabdomyosarcomatous components and later development of growing teratoma syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2012; 6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mrabti H, El Ghissassi I, Sbitti Y, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome and peritoneal gliomatosis. Case Rep Med 2011; 2011:123527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kikawa S, Todo Y, Minobe S, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome of the ovary: a case report with FDG-PET findings. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2011; 37:929–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sengar AR, Kulkarni JN. Growing teratoma syndrome in a post laparoscopic excision of ovarian immature teratoma. J Gynecol Oncol 2010; 21:129–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rashmi, Radhakrishnan G, Radhika AG, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome: a rare complication of germ cell tumors. Indian J Cancer 2010; 47:486–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsushita H, Arai K, Fukase M, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome of the ovary after fertility-sparing surgery and successful pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2010; 69:221–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzortzatos G, Sioutas A, Schedvins K. Successful pregnancy after treatment for ovarian malignant teratoma with growing teratoma syndrome. Fertil Steril 2009; 91:936.e1-e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh TY, Cheng YM, Chang FM, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome: an Asian woman with immature teratoma of left ovary after chemotherapy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 48:186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hariprasad R, Kumar L, Janga D, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome of ovary. Int J Clin Oncol 2008; 13:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tangjitgamol S, Manusirivithaya S, Leelahakorn S, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome: a case report and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006; 16:384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dewdney S, Sokoloff M, Yamada SD. Conservative management of chylous ascites after removal of a symptomatic growing retroperitoneal teratoma. Gynecol Oncol 2006; 100:608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umekawa T, Tabata T, Tanida K, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome as an unusual cause of gliomatosis peritonei: a case report. Gynecol Oncol 2005; 99:761–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rekha W, Amita M, Sudeep G, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome in germ cell tumour of the ovary: a case report. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2005; 45:170–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nimkin K, Gupta P, McCauley R, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome. Pediatr Radiol 2004; 34:259–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inaoka T, Takahashi K, Yamada T. The growing teratoma syndrome secondary to immature teratoma of the ovary. Eur Radiol 2003; 13:2115–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itani Y, Kawa M, Toyoda S, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome after chemotherapy for a mixed germ cell tumor of the ovary. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2002; 28:166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.David YB, Weiss A, Shechtman L, et al. Tumor chemoconversion following surgery, chemotherapy, and normalization of serum tumor markers in a woman with a mixed type germ cell ovarian tumor. Gynecol Oncol 2002; 84:464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geisler JP, Goulet R, Foster RS, et al. Growing teratoma syndrome after chemotherapy for germ cell tumors of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol 1994; 84:719–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kattan J, Droz JP, Culine S, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome: a woman with nonseminomatous germ cell tumor of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 1993; 49:395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jumean HG, Komorowski R, Mahvi D, et al. Immature teratoma of the ovary—an unusual case. Gynecol Oncol 1992; 46:111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moskovic E, Jobling T, Fisher C, et al. Retroconversion of immature teratoma of the ovary: CT appearances. Clin Radiol 1991; 43:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aronowitz J, Estrada R, Lynch R, et al. Retroconversion of malignant immature teratomas of the ovary after chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 1983; 16:414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]