Abstract

Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumors (ES/PNET) are high-grade malignant neoplasms. These malignancies present very rare tumors of thoracopulmonary area and even rarer in the mediastinum. In our knowledge, ES/PNET presented with multiple mediastinal masses has not been reported previously.

We experienced a case of a 42-year-old man presented with gradual onset of left-side pleuritic chest pain. A contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed separate 2 large heterogeneously enhancing masses in each anterior and middle mediastinum of the left hemithorax. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan revealed high fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the mediastinal masses. After surgical excision for the mediastinal masses, both of the masses were diagnosed as the ES/PNET group of tumors on the histopathologic examination. The patient refused postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and came back with local tumor recurrence and distant metastasis on 4-month follow-up after surgical resection.

We report this uncommon form of ES/PNET. We are to raise awareness that this rare malignancy should be considered as a differential diagnosis of the malignant mediastinal tumors and which can be manifested as multiple masses in a patient. Understanding this rare entity of extra-skeletal ES/PNET and characteristic imaging findings can help radiologists and clinicians to approach proper diagnosis and better management for this highly malignant tumor.

INTRODUCTION

The ES/PNET group of tumors are primary malignant tumors of bone and soft tissue that consist of small round tumor cells.1 These uncommon and highly malignant tumors primarily affect children and young adults, but can occur in any age group.2,3

Extra-skeletal ES/PNET is rare in comparison with skeletal ES/PNET.4 Extra-skeletal ES/PNET is a rare disease that may develop in soft tissues at any location.3 Common sites of occurrence are the trunk, extremities, and retroperitoneum.3 Primary thoracopulmonary ES/PNET is the single most common form of extra-skeletal ES/PNET,5 but primary mediastinal location of the extraskeletal ES/PNET is extremely rare.1,2 And tumors show aggressive features with a high incidence of local recurrence and distant metastases.2,5

In our search for the literature, ES/PNET presented with multiple mediastinal masses has not been reported previously. In our case report, we review a unique case of this rare form of extra-skeletal ES/PNET presented as separate masses in different mediastinal compartments.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Ethics committee approval is not included as it is commonly accepted that case reports do not require such approval. Because our work did not use patients’ data that would allow identifying them, informed consent is not necessary.

A CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old Korean man visited our outpatient clinic with pleuritic left chest pain since a month. He also complained frequent and vigorous cough and chest pain was aggravated when coughing and breathing. He lost 3 kg of body weight during the past 1 month. The patient revealed no specific medical history. His physical examination showed dullness to percussion and decreased vocal fremitus on left hemithorax. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was increased of 487 U/L (normal range, 0–250 U/L). Otherwise, the results of initial laboratory tests including complete blood count, chemistry panel, and urine analysis revealed no remarkable abnormality.

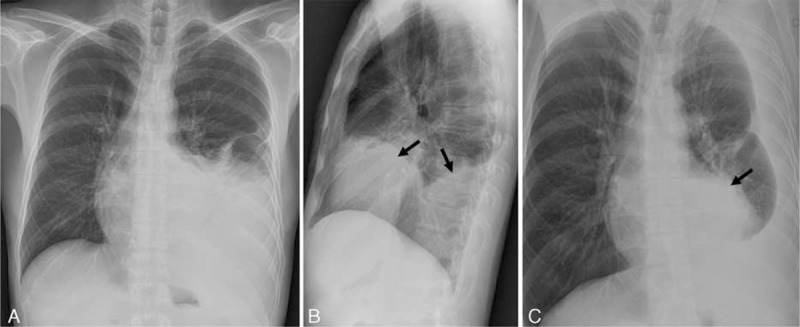

On initial chest radiographs after admission showed moderate amount of left pleural effusion with contralateral mediastinal shifting and obliteration of left cardiac and diaphragmatic margins on frontal view (Figure 1A and B). There were seen large contour bulging mass opacities in left lower hemithorax on lateral view (arrows in Figure 1B), which were seen as well-defined masses overlapped with left cardiac shadow on left side down decubitus view with fluid shifting (arrow in Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Initial chest radiographs on admission in a 47-year-old man. Chest posterior anterior (A), left lateral (B), and left decubitus (C) views show moderate amount of left pleural effusion. Left lateral (B) and left decubitus (C) views reveal anterior and posterior mediastinal contour bulging mass opacities (black arrows in B and C), which are obscured on chest posterior anterior view (A).

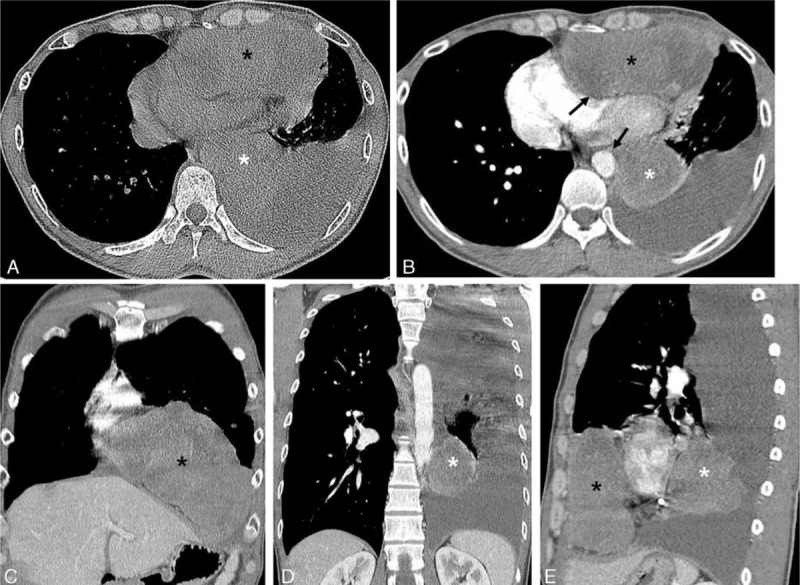

Findings of pre- and postcontrast-enhanced chest CT (Figure 2A–E) revealed heterogeneously enhancing (20–80 Hounsfield unit) well-defined 2 separate large masses, which were located in each anterior and middle mediastinum of the left lower hemithorax. The larger one of the masses in left anterior mediastinum (black asterisk in Figure 2) was measured about 15.0 × 9.0 × 8.0 cm, which showed broad contact with the left chest wall anteriorly, mass effect with compression resulting in contour deformity of the adjacent left cardiac chambers posteromedially on axial scan (Figure 2B) and inversion of the left diaphragm inferiorly on coronal scan (Figure 2C). The other separate smaller mass in the middle mediastinum of the left lower hemithorax (white asterisk in Figure 2) was measured about 6.0 × 6.6 × 6.8 cm, which was located between posterior wall of the left ventricle and left lateral wall of the descending thoracic aorta on axial and coronal scans (white asterisk in Figure 2B and D). Intervening mediastinal fat plane between those masses and adjacent mediastinal structures seemed to be preserved (black arrows in Figure 2B) with compression and contour deformity of the left cardiac chambers and no definite evidence of direct tumor invasion. There was seen moderate amount of left pleural effusion with mild pleural enhancement (Figure 2B, D, E). No significant mediastinal lymphadenopathy was seen.

FIGURE 2.

Pre- and contrast-enhanced chest CT scans in a 47-year-old man. Axial pre- (A) and contrast-enhanced (B) chest CT scan with mediastinal window images show 2 separate masses in left anterior (black asterisk) and posterior mediastinum (white asterisk), which show heterogenous enhancement with low-density areas after intravenous contrast administration (B). Extrinsic compression with contour deformity of the left cardiac chambers and left lateral wall of descending thoracic aorta is seen; however, intervening fat plane between the masses and mediastinal structures seems to be preserved (black arrows in B). Moderate amount of left pleural effusion is noted (B, D, E). Coronal (C, D) and sagittal (E) reconstruction images show 2 separate masses in left anterior (black asterisk in C and E) and posterior (white asterisk in D and E) mediastinum and well demonstrated anatomical relationship of the 2 mediastinal masses. CT = computed tomography.

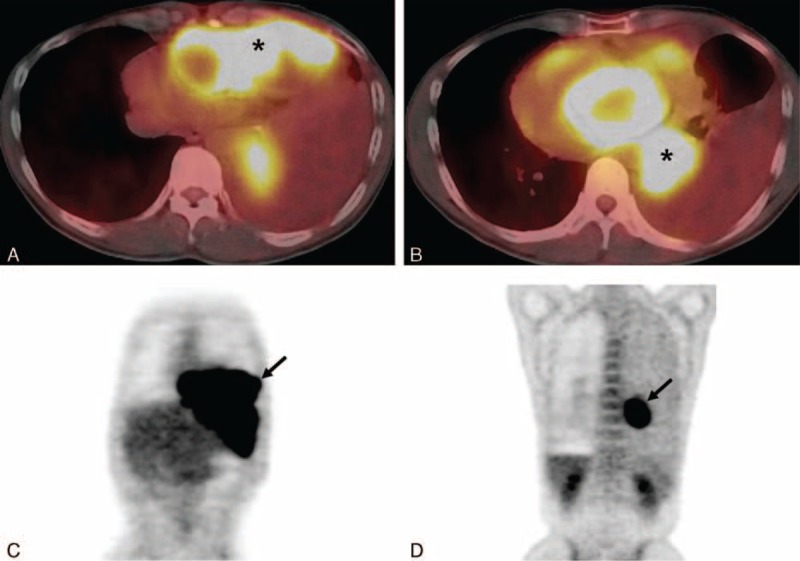

Chest magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not performed in our patient and initial radiologic differential diagnoses included tumor of thymic origin with metastasis, malignant lymphoma, malignant neurogenic tumors, malignant germ cell tumor with metastasis, malignant mesenchymal tumors based on the findings of chest CT scan. Subsequently performed PET-CT scan showed increased maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax 8.3) of FDG for each of the anterior and middle mediastinal masses (Figure 3A–D).

FIGURE 3.

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan in a 47-year-old man. Axial fusion images (A, B) show increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptakes (maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax, 8.3) in the anterior and posterior mediastinal masses (each asterisk in A, B). Torso maximum intensity projection images (C, D) reveal increased FDG uptake in each of the anterior (arrow in C) and posterior (arrow in D) mediastinal masses. FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose.

Based on imaging findings on chest CT and PET-CT scans, malignant mediastinal masses were highly considered. After multidisciplinary discussion with the attending physician, chest radiologist, and thoracic surgeon, we decided a surgical approach with excision of the mediastinal masses for the proper diagnosis and management.

The surgical approach with lateral thoracotomy and excision of the mediastinal masses was performed. On operation field, there were seen highly vascularized anterior and middle mediastinal masses in left lower hemithorax. Those masses were tightly adhered to adjacent pleura, pericardium, diaphragm, and lungs. The left anterior mediastinal mass was more than double adult fist-sized with lobulation, which tightly attached to left 6th costal cartilage. Upper portion of the left anterior mediastinal mass was well encapsulated, whereas lower portion of the tumor was easily ruptured with necrosis. A separate left middle mediastinal mass was identified and which was well encapsulated with less than adult fist-sized and rugged surface. Those left anterior and middle mediastinal masses revealed their blood supply from intercostal arteries and also small feeding arteries from the descending thoracic aorta, respectively. The patient well recovered with no immediate and delayed postoperative complication.

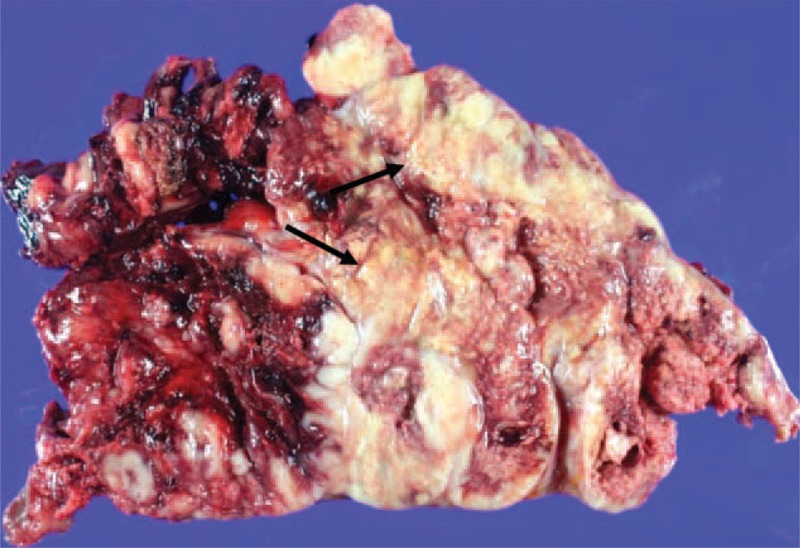

On gross histopathologic examination, the tumors were seen as multilobulated, friable, soft masses, totally weighing 654 g and measuring 19 × 13 × 6 cm in the larger one. On cross section, the cut surface has a gray-yellow and gray-tan appearance with multifocal areas of necrosis (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Gross specimen of the left anterior mediastinal mass. Grossly the tumor reveals a multilobulated, friable, soft mass with areas of multifocal necrosis (black arrows).

Microscopically, the tumors revealed lobular growth pattern with hemorrhage and extensive necrosis on low magnification (Figure 5A). The tumor was composed of uniform round blue cells with inapparent, small nucleoli, and scanty cytoplasm (Figure 5B). On immunohistochemical stain, the tumor cells showed strong membranous staining for CD99 (Figure 5C). These findings were consistent with ES/PNET and histologic findings were identical in the 2 separate masses. And resection margins and dissected adjacent pleura were free from tumor cells.

FIGURE 5.

Histopathologic findings of the mediastinal tumor. On microscopy, the tumor shows lobular growth pattern with extensive necrosis (black arrows) (×40, H&E) (A). The tumor is composed of uniform round blue cells with inapparent, small nucleoli, and scanty cytoplasm (×400, H&E) (B). On immunohistochemical stain, the tumor cells show strong membranous staining for CD99 (×400, CD99) (C).

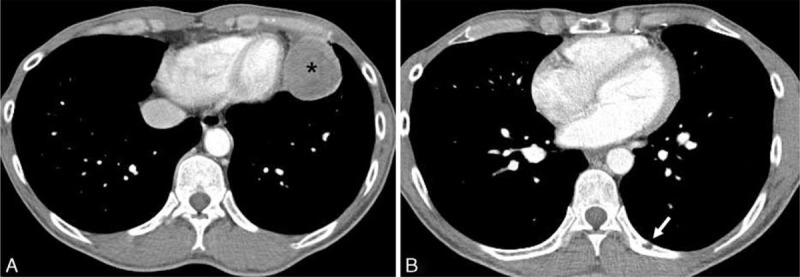

With consideration of aggressive behavior of the tumor, postoperative chemotherapy was recommended. However, the patient refused further treatment and discharged. Four months later, chest CT and PET-CT scans were performed in our out-patient clinic for routine postoperative follow-up evaluation. The follow-up chest CT scan again revealed a recurrent mediastinal mass at paracardiac area of the left lower hemithorax (asterisk in Figure 6A), which showed increased FDG uptake on PET-CT scan (not shown). Also a focal osteolytic lesion was newly appeared on left 9th posterior rib suggesting bone metastasis (white arrow in Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Follow-up contrast-enhanced chest CT scan 4 months after the mediastinal tumor excision in a 47-year-old man. Axial contrast-enhanced chest CT scan performed on postoperative 4-month follow-up shows a recurrent heterogeneously enhancing left anterior mediastinal mass (asterisk) in the left paracardiac area (A). A newly appeared focal osteolytic metastatic lesion (arrow) is noted on posterior arc of the left 9th rib (B). CT = computed tomography.

DISCUSSION

Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumors represent a family of high-grade small round cell tumors, which have neuroectodermal origin and show varying degrees of neuronal differentiation.2,5 The Ewing sarcoma family of tumors includes classic Ewing sarcoma of bone, extra-skeletal Ewing sarcoma, Askin tumors of the chest wall, and primitive neuroectodermal tumors of bone or soft tissues.2–4 The family of ES/PNET tumors can be united as a tumor entity by the presence of a reciprocal translocation of the long arms of chromosomes 11 and 22, t (11;22)(q24;q12), so-called EWS (Ewing sarcoma protein)-friend leukemia virus integration-1 (FLI-1) fusion gene.2,6

These highly malignant tumors are reported commonly in children and young adults, which show ∼80% of patients being in their first 2 decades of life.2,5 And ∼80% of these tumors occur in the skeletal system, which tend to involve the diaphysis or metaphyseal-diaphyseal regions of long bones.5,7 Extraskeletal ES/PNETs are quite rare than skeletal ES/PNETs and common location of extraskeletal ES/PNETs is thoracopulmonary area.5,8 Among the thoracopulmonary ES/PNETs, primary mediastinal ES/PNETs are very rare.1,2 In our search for the radiology literature, only 7 cases of primary ES/PNETs of the anterior or middle mediastinal location have been reported.2,8 To our knowledge, ES/PNET presented with multiple mediastinal masses in different mediastinal compartments has not been reported.

The classic histologic finding of ES/PNET is made up of solid sheets of small round blue cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and scant eosinophilic cystoplasm (Figure 5B).2,3,6 Wright-type rosettes can be identified in the more neurally differentiated tumors.9 However, these histologic patterns are not specific morphologic features. Then, it is hard to differentiate the ES/PNET from similar other small round blue cell tumors such as embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, and lymphoma by a standard microscope alone.2,9 Immunohistochemical staining is helpful in differentiating ES/PNET from other small round blue cell tumors.2,6,9 The ES/PNET group of tumors has a common cell surface glycoprotein marker, cluster of differentiation 99 (CD99), which is a product of major histocompatibility complex class I-related (MIC) 2 gene.2,3,6 And positive finding of other markers, including FLI-1, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), vimentin, also can be helpful for diagnosis of ES/PNET.2,6 Molecular genetic techniques, such as fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH), reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can be used for definitive diagnosis for the ES/PNET.1,9 Identification of the t (11;22)(q24;q12) chromosomal translocation (EWS-FLI1 gene fusion) is highly specific for ES/PNET, because >90% of the tumors show this gene rearrangement.9

On chest CT scan, ES/PNET usually manifests as a large unilateral heterogeneously enhancing mass, often with low attenuating necrosis or cystic areas and high attenuating hemorrhage.2,10 The tumor tends to displace rather than encase adjacent structures such as vessels, the trachea/bronchi, or the mediastinum,10 which finding also can be well recognized in our case. Calcification of the mass is relatively rare and can be seen in ∼10 % of the tumors.2,10 Lymph node metastasis is also rarely seen.2,10 Interestingly, distant metastasis is rare at the time of diagnosis in the thoracopulmonary ES/PNET, but after treatment, including excision, chemotherapy, and local radiation therapy, the tumor shows tendency of frequent local recurrence and distant metastasis as seen in our case.2,5 In case of thoracopulmonary ES/PNET, the tumor is frequently associated with adjacent rib or sternum destruction and pleural effusion.2,4,5

In our case, the mediastinal tumors revealed relatively typical CT features, which include heterogeneously enhancing large masses with areas of low attenuation corresponding tumor necrosis on gross specimen. No calcification was identified and there was no lymph node metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis. Our case presented as separate 2 synchronous masses in each anterior and middle mediastinum at initial diagnosis. We think it is not certain whether those 2 separate mediastinal masses are synchronous multiple primary tumors or a malignant tumor with metastasis. And unfortunately, local tumor recurrence was identified on postoperative 4-month follow-up chest CT scan in our patient, in whom adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy were not performed.

Magnetic resonance imaging similarly shows a large heterogeneous mass with typically isointense to slightly hyperintense on T1-weighted image and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted image when compared to skeletal muscle.4,5 Prominent areas of high-signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images represent hemorrhage and necrosis.4,5 The tumors show variable enhancement patterns after intravenous contrast material administration, depending on tumor size, degree of necrosis, and hemorrhage.4,5,10 MRI can be more useful than CT scan in delineating chest wall invasion.4,5

Combination of surgical excision, chemotherapy and radiotherapy is known to standard treatment for the ES/PNET group of tumors.3–5 Although optimal combination of chemotherapeutic agents is yet to be established, combination therapy including vincristine, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, and actinomycin D (VACA) is known to standard first-line treatment.3 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can also be considered to eliminate micrometastases and reduce the size of primary bulky tumor mass before surgical excision.4,5

The ES/PNET group of tumors has been known to have poor prognosis.2,4 Askin et al reported median survival of only 8 months after the diagnosis of the tumor.4 However, recent studies show significant improvement in 5-year overall survival of exceeding 60% to 65% for localized ES/PNET with a combination of surgical excision, intense chemotherapy, and high-dose radiotherapy.3 Most important prognostic factors are known as tumor size, presence of distant metastasis at presentation, and surgical resection margin.3,9 Resection margins were free from tumor cells, but postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy were not performed in our case due to patient's refusal of treatment and the clinical course of the patient well represents highly malignant characteristics and behavior of the ES/PNET as previously reported.2,5

Based on radiologic findings in our case of extra-skeletal ES/PNET manifested as multiple mediastinal masses and previous literature review, the imaging feature of the tumor is relatively typical appearance of malignant tumors although which is nonspecific. Therefore, it is difficult to differentiated ES/PNET from other malignant mediastinal tumors, especially in the case of anterior mediastinal location. In our routine practice, more common anterior mediastinal tumors, including thymic carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, nonseminomatous germ cell tumor, share similar imaging findings and confirmative histopathologic diagnosis is essential for definite diagnosis and management.2,7 Although the mediastinal ES/PNET is a rare tumor entity in adult patient, it should be considered as a differential diagnosis for malignant mediastinal tumors and which can be manifested as multiple masses in a patient. Understanding this rare entity of extra-skeletal ES/PNET and characteristic imaging findings can help radiologists and clinicians to approach proper diagnosis and better management for this highly malignant tumor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CD99 = Cluster of differentiation 99, CT = computed tomography, ES/PNET = Ewing Sarcoma/Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumors in the Mediastinum, EWS = Ewing sarcoma protein, FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose, FISH = fluorescent in-situ hybridization, FLI-1 = Friend leukemia virus integration-1, LDH = lactate dehydrogenase, MIC = major histocompatibility complex class I-related, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, NSE = neuron-specific enolase, PET-CT = Positron emission tomography-computed tomography, RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, SUVmax = maximum standardized uptake value, U/L = unit per liter, VACA = vincristine adriamycin cyclophosphamide and actinomycin D.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrei M, Cramer SF, Kramer ZB, et al. Adult primary pulmonary primitive neuroectodermal tumor: molecular features and translational opportunities. Cancer Biol Ther 2013; 14:75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang WD, Zhao LL, Huang XB, et al. Computed tomography imaging of anterior and middle mediastinal Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumors. J Thorac Imaging 2010; 25:168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Weshi A, Allam A, Ajarim D, et al. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma family of tumours in adults: analysis of 57 patients from a single institution. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2010; 22:374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphey MD, Senchak LT, Mambalam PK, et al. From the radiologic pathology archives: Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2013; 33:803–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Javery O, Krajewski K, O’Regan K, et al. A to Z of extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma family of tumors in adults: imaging features of primary disease, metastatic patterns, and treatment responses. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197:W1015–W1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folpe AL, Goldblum JR, Rubin BP, et al. Morphologic and immunophenotypic diversity in Ewing family tumors: a study of 66 genetically confirmed cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29:1025–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tecce PM, Fishman EK, Kuhlman JE. CT evaluation of the anterior mediastinum: spectrum of disease. Radiographics 1994; 14:973–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young Jae Sung MD, Jeung Sook Kim MD. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of mediastinum in an adult: a case report. J Korean Soc Radiol 2009; 61:5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manduch M, Dexter DF, Ellis PM, et al. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the posterior mediastinum with t(11;22)(q24;q12). Tumori 2008; 94:888–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dick EA, McHugh K, Kimber C, et al. Imaging of non-central nervous system primitive neuroectodermal tumours: diagnostic features and correlation with outcome. Clin Radiol 2001; 56:206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]