Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Abstract

It remains unclear whether the efficacy of nonsurgical organ-preservation modalities (NOP) in the treatment of advanced-stage laryngeal cancer was noninferiority compared with that of total laryngectomy (TL). The objective of this study was to compare the curative effects between TL and NOP in the treatment of advanced-stage laryngeal cancer through a meta-analysis.

Clinical studies were retrieved from the electronic databases of PubMed, Embase, Wanfang, and Chinese National Knowledge infrastructure. A meta-analysis was performed to investigate the differences in the curative efficacy of advanced-stage laryngeal cancer between TL and the nonsurgical method. Two reviewers screened all titles and abstracts, and independently assessed all articles. All identified studies were retrospective.

Sixteen retrospective studies involving 8308 patients (4478 in the TL group and 3701 in the nonsurgical group) were included in this meta-analysis. The analysis results displayed the advantage of TL for 2-year and 5-year overall survival (OS)(OR 2.79, 95% CI 1.85–4.23 and OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.09–2.14) as well as in 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS)(OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.61–1.98), but no significant difference in 2-year DSS was detected between the 2 groups (OR = 2.09,95% CI0.69–6.40). Additionally, there were no significant differences between TL and NOP for 5-year local control (LC) either (OR = 1.75, 95% CI 0.87–3.53). When we carried out subgroup analyses, the advantage of TL was especially obvious in T4 subgroups, but not in T3 subgroups.

This is the first study to compare the curative effects on advanced-stage laryngeal cancer using meta-analytic methodology. Although there was a trend in favor of TL for OS and DSS, there is no clear difference in oncologic outcome between TL and NOP. Therefore, other factors such as tumor T-stage and size, lymph node metastasis, and physical condition are also important indicators for treatment choice.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer of the larynx is among the most common cancers of the head and neck, with almost 110,000 to 130,000 new cases diagnosed worldwide annually.1,2 Most of these cancers are squamous cell carcinoma, accounting for 85% to 95% of laryngeal malignant neoplasms.3 The large majority of laryngeal cancer patients diagnosed are in early stage which has a highly cure rate, with 5-year locoregional control rate approaching 90%.4 However, the therapy effects of advanced laryngeal cancer (stage III or IV) is extremely poorer than that in early stages. Advanced stage of laryngeal cancer is associated with a higher rate of relapse and cancer-related death, having crucial influence on overall prognosis. Increasing patients have already been in advanced stages, especially in the IV phase, when they are diagnosed.5 There were 2 different treatment strategies for advanced laryngeal cancer, namely total laryngectomy (TL) and nonsurgical organ-preservation modalities (NOP). The implementation of the latter includes vital conservation surgeries such as partial vertical laryngectomy (extending hemilaryngectomy), near laryngectomy with epiglottic reconstruction and supracricoid partial laryngectomy (with cricohyo-idoepiglottopexy reconstruction), and big nonsurgical organ-preservation treatments such as chemoradiation (CRT) and radiotherapy (RT). However, TL followed by RT or other therapeutic strategy provided no significant improvement in survival time in the past 30 years.6 Until now, the constituent of optimal treatment modality for advanced stage larynx cancers still has been mightily debated in medical research. One of the most controversial questions is the choice between conventional TL and organ preservation with nonsurgical treatment when facing advanced-stage laryngeal cancer. TL for laryngeal carcinoma results in the loss of vocal function, which was a major disadvantage of this method. The target of larynx-preservation approaches is to preserve the functional organ; nevertheless we worry over the survival rate and time when using such treatments. Whether the survival rate and time of patients with advanced-stage larynx cancer treated with NOP are noninferiority compared with those who are treated with TL? Which therapeutic strategy is optimal? Neither do we know. Some researchers have made efforts to preserve the larynx with nonsurgical treatment regiments that can improve quality of patients’ life and retain physiological function of larynx without compromising survival. Other scholars, however, believe that many situations should be considered as the basis of treatment choice, such as tumor size, the status of tumor invasion and lymph node metastasis, patient's performance status, and so on. Consequently, multiple studies have compared the 2 treatments of advanced laryngeal cancer. The objective of this study was to compare the effects between TL and NOP in the treatment of advanced-stage laryngeal cancer via a meta-analysis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the 2 methods using meta-analytic methodology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature Search Strategy

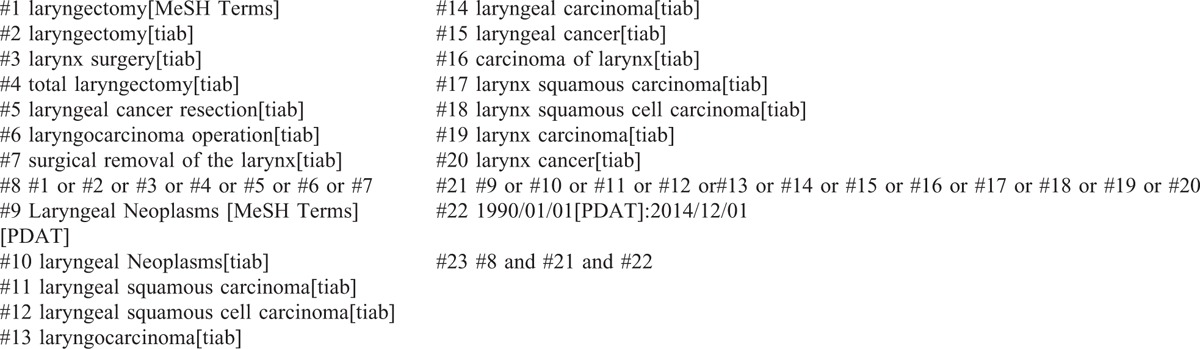

Literature searching was conducted in the 2 English databases of PubMed from January 1, 1990, to December 1, 2014, and Embase from 1990 to 2014, and in the 2 Chinese databases of Wanfang and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure from 1990 to 2014. Additionally, reference lists and conference proceedings were also checked to identify possibly additional clinical trials. The search strategies used for PubMed and Embase are illustrated in Table 1 and Table 2. Meanwhile, we searched these 2 Chinese databases using the search terms “laryngeal cancer” and “total laryngectomy” to identify potential studies for the analysis. Finally, we screened the references in all reviewed articles to identify additional articles that were not retrieved in the literature search described above.

TABLE 1.

PubMed Search Strategies

TABLE 2.

Embase Search Strategies

Selection Criteria

This meta-analysis included all studies meeting the following criteria: (a) clinic trials compared the curative effects between primary TL and primary RT or CRT; (b) patients with nonmetastatic advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) were biopsy-proved and untreated previously; (c) laryngeal cancer included any supraglottic, glottic, or subglottic lesions; (d) original articles provided sufficient information for meta-analysis; and (e) papers were published in Chinese or English language. The study does not involve patient consent, so ethical approval is not necessary for this study.

Data Extraction

Information from each study was abstracted independently by 2 investigators using a standardized data extraction form which were predesigned based on the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group data extraction template. The data included first author's name, publication year, study design, country of origin, numbers of patients after divided into various subgroups according to age, sex, tumor site, and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classifications. Any disagreement over extracted data was resolved through discussion between the 2 investigators to reach a consensus. The primary endpoint was OS. The secondary endpoints contained DSS and LC. When key pieces of information were not presented in the article, the corresponding author was contacted. In the event that the given information was still not available, it was classified as “not reported.”

Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts for initial relevance evaluation. For all initially retrieved articles, if either reviewer considered any titles or abstracts meeting the eligibility criteria, their full-text form were then obtained. The quality and bias risk of the papers were critically appraised separately by 2 reviewers. Quality assessment was conducted in each of the eligible studies by using the validated Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies.7,8 This scale is composed of 8 items that assess patient selection, study comparability and outcome with scores ranging from 0 to 9. In our selection criteria, the studies with a score no <6 were regarded as high quality. Eventual consensus governance resolved disagreements.

Statistical Methods

Dichotomous results were summarized as pooled odds ratios (ORs) or weighted mean differences and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) around the point estimates using a random effects model given the assumption that included studies were only representative samples of all potentially available studies. The test for overall pooled effect used the z-statistic with P value ≤0.05 representing statistical significance.

The homogeneity of the estimates was formally tested using the X2 statistic with degrees of freedom and P value reported. The I2 test was used to measure the extent of inconsistency among results and the proportion of total variability described by heterogeneity rather than chance alone. The predetermined significance level of heterogeneity was P≤0.10. All statistical analyses were carried out using the RevMan 5.2 software.

RESULTS

Search Results

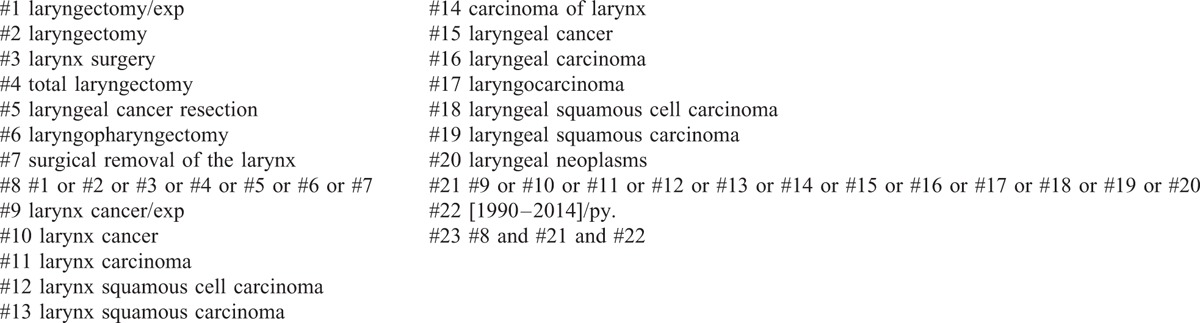

A total of 8308 citations were identified from the electronic databases. We excluded 2895 publications due to the duplication of the studies. In the review of the titles and abstracts of remained 5413 articles, we further excluded 5333 ones. According to the inclusion criteria established for the present study, additional 64 articles were excluded. We thus finally selected 16 studies in this study, which included 8179 patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. All studies were retrospective cohort study. The basic characteristics of the included studies are listed in supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Content. The flowchart of this search process is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart for study selecting.

Among the 16 selected studies, 5 of them were included in the pooled analysis of the 2-year OS, 12 of them were included in the analysis of 5-year OS, 2 of them were included in the analysis of 2-year DSS, 6 of them were included in the analysis of 5-year DSS, 2 of them were included in the analysis of 2-year LC, and 4 of them were included in the analysis of 5-year LC. Quality assessment with Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies demonstrated the combined scores of selection, comparability and outcome were higher than 5 in each of the selected 16 studies.9–24 The scores are listed in supplementary Table 2, Supplemental Content.

Clinical and Methodological Heterogeneity

The included studies are all retrospective designs. Multiple respects in these studies could affect their findings on OS, DSS, and LC, including various diversities in populations of the study samples, in the schemes of chemotherapy, in the strategies of RT, in the proportions of patients in stage IV, in patients’ performance status levels, and in the methods to detect recurrence. Therefore, there was considerable clinical and methodological heterogeneity among the included studies.

We have marked sensitivity analysis on the data. Neither the OS nor the DSS of the estimated pooled results was obviously affected when each study was removed in the sensitivity analysis, indicating that no single study dominated our results. Our sensitive analysis showed that the study by Megwalu and Sikora contributed significant heterogeneity to our results. We considered that the heterogeneity might come from the significantly bigger sample size than others. And it was a population-based, nonconcurrent cohort study, the patients selecting is different from other studies.

Statistical Pooling

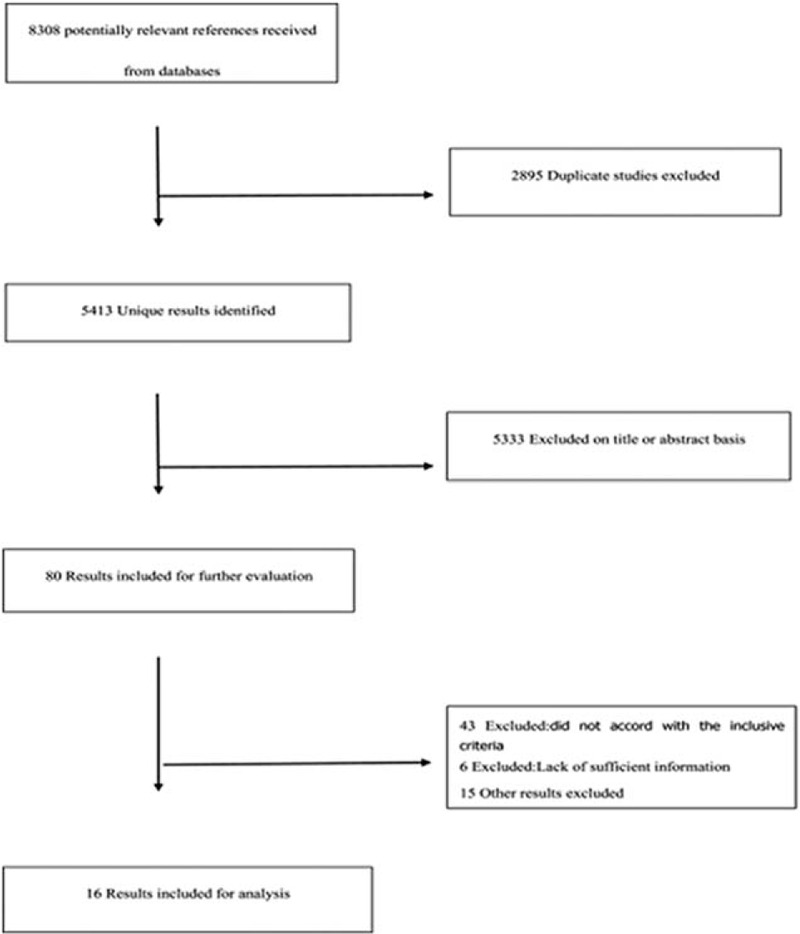

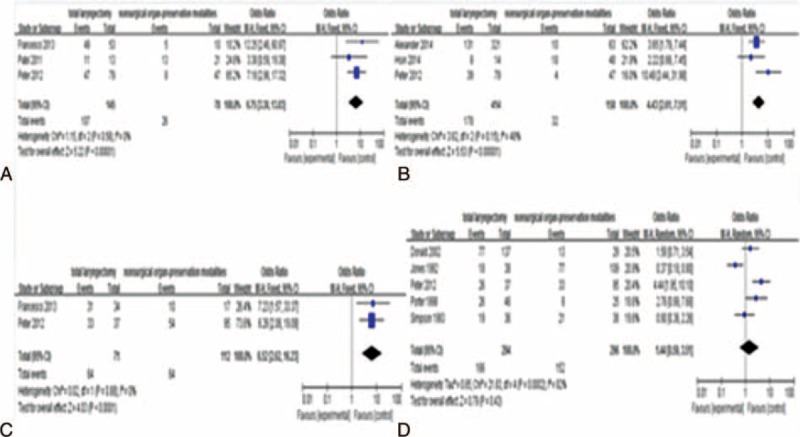

The pooled results showed that compared with nonsurgical treatment, TL was associated with longer survival time, both for 2-year and for 5-year (OR 2.79, 95% CI 1.85–4.23, P < 0.00001; Figure 2A and OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.09–2.14, P = 0.01; Figure 2B). The difference in T4 subgroup was more significant (OR = 6.75, 95% CI 3.30–13.83, P < 0.00001; Figure 3A and OR = 4.43, 95% CI 2.61–7.51, P < 0.00001; Figure 3B). In the T3 subgroup, the difference appeared in 2-year OS (OR = 6.52, 95% CI 2.62–16.23, P < 0.00001; Figure 3C), but not in 5-year OS (OR = 1.44, 95% CI 0.59–3.51, P = 0.43; Figure 3D).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of overall survival (2-year overall survival, A; 5-year overall survival, B) between total laryngectomy (TL) and nonsurgical organ-preservation modalities (NOP). CI = confidence interval; NOP = nonsurgical organ-preservation; OR = odds ratio; TL = total laryngectomy.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison between the treatment groups for T4 (2-year overall survival for T4, A; 5-year overall survival for T4, B)and T3 (2-year overall survival for T3, C; 5-year overall survival for T3, D) overall survival. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

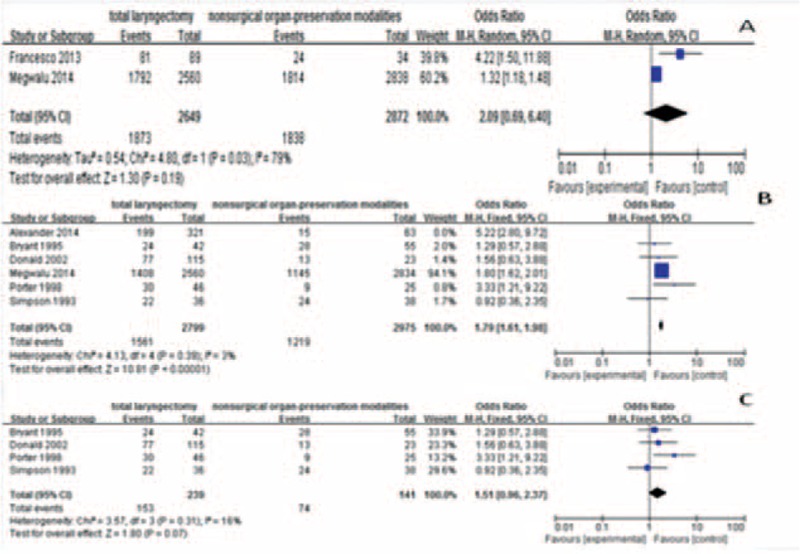

In terms of 2-year DSS, there was no significant difference (OR = 2.09, 95% CI0.69–6.40, P = 0.19; Figure 4A) between patients with advanced stage laryngeal cancer who were treated with TL and those who underwent nonsurgical therapy. But the analysis result was in favor of TL in 5-year DSS (OR = 1.79, 95% CI 1.61–1.98, P < 0.00001; Figure 4B). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the 5-year DSS between the 2 treatment groups had no statistical difference in the T3 stage (OR = 1.51, 95% CI 0.96–2.37, P = 0.07; Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Comparison between the treatment groups for disease-specific survival (2-year disease-specific survival, A; 5-year disease-specific survival, B; 5-year disease-specific survival forT3, C). CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

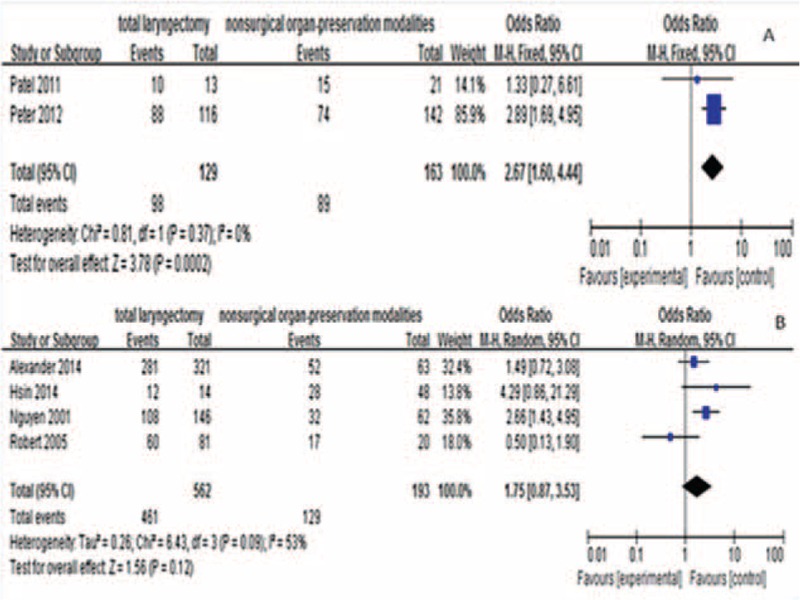

In addition, we found that patients treated with TL had improved 2-year LC compared with patients treated with nonsurgical treatment (OR = 2.67, 95% CI 1.60–4.44, P = 0.0002; Figure 5A). But there were no significant difference between TL and NOP for 5-year LC (OR = 1.75, 95% CI 0.87–3.53, P = 0.12; Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison between the treatment groups for local control (2-year local control, A; 5-year local control, B). CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

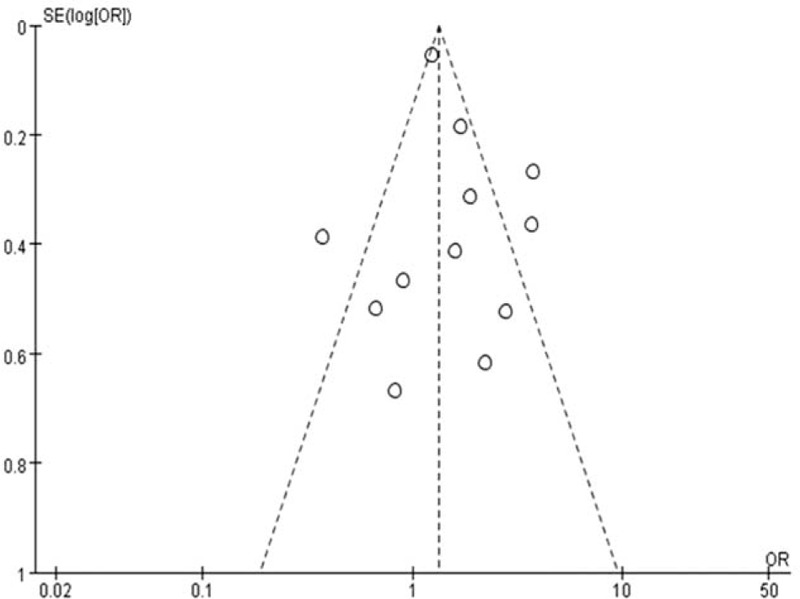

In the meta-analysis performed, the funnel plots were symmetrical (Figure 6). These results indicate that it is unlikely that publication bias was significant across included studies.

FIGURE 6.

Funnel plot for publication bias.

DISCUSSION

The quality of the available literature with respect to the treatment of advanced-stage laryngeal cancer is limited–no randomized controlled trial (RCT) was identified, and the majority of studies on this topic had a small sample size, making detailed and meaningful outcome analysis difficult. In terms of complications, due to the significant heterogeneity in the literature, there may produce incorrect results if use meta-analysis research, so we give up using meta-analysis.

Until now, only a few reviews summarized the contrast of curative effects between TL and nonsurgical treatment on advanced laryngeal cancer, but no system evaluation involved this aspect. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis of 16 published studies to evaluate the differences of survival outcomes between surgical therapy and laryngeal conservation in the treatment of advanced laryngeal cancer. First, we compared 2-year OS between the 2 groups. A total of 5 studies included could not be merged into this comparison because of significant heterogeneity. Considerable heterogeneity resulting from the data was not accuracy of individual, so we get rid of the worst reported by Megwalu and Sikora.9 It was a population-based, nonconcurrent cohort study, and the data were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results 18 Database. The 2-year OS rates in patients treated with TL and nonsurgical treatment were 78.8% and 52.9%, respectively. These results indicated patients treated with surgery had higher survival rate (P < 0.00001). In subgroup analysis of T-stage, the T3 (P < 0.0001) and T4 (P < 0.00001) subgroups had the same results. However, the result of 5-year OS was slightly different. Specifically, the 5-year OS in patients treated with TL was superior to that in patients with nonsurgical treatment (P = 0.04), but the difference was not significant. Besides, there was no statistical difference between the 2 groups in T3 subgroup analysis (P = 0.11), whereas significant difference was found in the T4 subgroup analysis (P < 0.00001). Then, we compared 2 years DSS, as a result, no statistical difference was detected between the 2 groups. Due to limited number of included studies, we did not perform subgroup analysis for 2-years DSS. But, the 5-year DSS in patients treated with TL was superior to that in patients with nonsurgical treatment (P < 0.00001), and the difference was statistically significant. Likewise, the advantage of TL in the 5-year DSS was also revealed in T4 subgroup analysis, though there was only 1 study. The comparison result of this article showed that 5-year DSS of T4 stage was higher in patients treated with TL than in those with nonsurgical modalities (P < 0.00001). Nevertheless, in the T3 subgroup analysis, this advantage was not existent any more. At last, we compared 2 years LC between the 2 groups, and found that the amalgamated 2-year LC rate was 76.0% and 54.6% in 129 patients treated with TL and in patients treated with nonsurgical modalities, respectively. These results indicated that TL provided higher LC rate than nonsurgical modalities (P = 0.0002). In the subgroup analysis, we find a same result in T4 subgroup (P = 0.002). However, there was no statistical difference in 5 years LC rate between the 2 groups.

The results of our meta-analysis manifested that comparing to nonsurgical modalities, TL might improve 2-year OS, 5-year OS, 5-year DSS, and 2-year LC, without statistically significant difference in 2-year DSS or 5-year LC. Therefore, we hypothesized that TL may be superior to nonsurgical modalities in improving long-term survival while may not possess a similar advantage for the local control rate. So, in the treatment of advanced-stage laryngeal cancer, TL cannot be indiscriminately considered superior to NOP modalities and vice verse. Then, what affect the survival outcomes of patients treated with nonsurgical treatment? For this question, the plausible explanations may lie in many aspects, such as multiple side-effect of treatments, as well as worse physical condition or other situations of the patients in the nonsurgical group. And this analysis was limited in terms of its small sample size, the difference method of RT and chemotherapy, diverse follow-up times, and various general situations of the patients. So we need more clinical trials to answer this question.

When we performed subgroup analysis, the advantage of TL expressed especially obvious in T4 subgroups, but there was no statistical difference between patients treated with TL and those treated with nonsurgical modalities in T3 subgroups. We thought about the possible reasons for this phenomenon. Tumor volumetry may be an important factor affecting the effects of radiation therapy. Dubben et al25 have found tumor volumetry is a basic predictor of the treatment response and survival among various types of cancer when treated with RT. Hsin et al10 investigated the impact of primary tumor volume on T4a laryngeal cancer patients and found that for tumor volume≥15 cm3, TL provided a significantly higher 5-year OS and PFS than definitive chemoradiotherapy (54.5% vs 22.5%, P = 0.039; 80.0% vs 32.2%, P = 0.017). Maybe the greater the tumor volume, the higher hypoxic content of the tumor, the more serious resistance to both RT and chemotherapy causes by hypoxic microenvironment. And for the larger volume, compared with the TL, to complete resection of tumor and its sub clinical range, present radiation technology is difficult to obtain the effect of complete elimination for T4 tumors. Then, T4 tumors maybe have more severe adverse effects when treated with CRT compared to cases that have undergone TL, because of larger clinical target volume. So, TL has a superior survival outcome when compared with CRT for T4 laryngeal cancer patients.

From this we infer that the T stage can affect the curative efficacy of treatment and it may be as a poor prognostic factor among advanced-stage laryngeal cancer patients treated with nonsurgical modalities. Therefore the T stage should be taken into account when choosing local therapeutic methods in order to improve the quality of decision making and to provide a better prediction of treatment outcome, especialy, to T4 N0 patients.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, for advanced-stage laryngeal cancer, no strong evidence for the superiority of TL to nonsurgical modalities was found in survival or locoregional control, but TL did express significant advantage in survival and locoregional control in patients with T4 laryngeal cancer. Choice of treatment, whether it be organ preservation or TL, it is not a simple question in the choice of treatments for advanced-stage laryngeal cancer, so regardless of using TL or nonsurgical modalities, the factors such as tumor T stage and size, lymph node metastasis, and physical condition should be important reference indicators for adopting more suitable treatments.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CRT = chemoradiation, DSS = disease-specific survival, LC = local control, NOP = nonsurgical organ-preservation modalities, OS = overall survival, RCT = randomized controlled trial, RT = radiotherapy, SCC = squamous cell carcinoma, TL = total laryngectomy.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57:43–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes L, Tse LY, Hunt JL. Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P, Sidransky D, et al. Tumours of the hypopharynx, larynx and trachea: introduction. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours.. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2005. 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendenhall WM, Werning JW, Hinerman RW, et al. Management of T1-T2 glottic carcinomas. Cancer 2004; 100:1786–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah JP, Karnell LH, Hoffman HT, et al. Patterns of care for cancer of the larynx in the United States. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 123:475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 2009; 59:225–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010; 25:603–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Megwalu UC, Sikora AG. Survival outcomes in advanced laryngeal cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 140:855–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsin LJ, Fang TJ, Tsang NM, et al. Tumor volumetry as a prognostic factor in the management of T4a laryngeal cancer. Laryngoscope 2014; 124:1134–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karatzanis AD, Psychogios G, Waldfahrer F, et al. Management of locally advanced laryngeal cancer. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 43:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bussu F, Paludetti G, Almadori G, et al. Comparison of total laryngectomy with surgical (cricohyoidopexy) and nonsurgical organ-preservation modalities in advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Head Neck 2013; 35:554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dziegielewski PT, O’Connell DA, Klein M, et al. Primary total laryngectomy versus organ preservation for T3/T4a laryngeal cancer: a population-based analysis of survival. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012; 41:S56–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel UA, Howell LK. Local response to chemoradiation in T4 larynx cancer with cartilage invasion. Laryngoscope 2011; 121:106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foote RL, Foote RT, Brown PD, et al. Organ preservation for advanced laryngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 2006; 28:689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sessions DG, Lenox J, Spector GJ, et al. Management of T3N0M0 glottic carcinoma: therapeutic outcomes. Laryngoscope 2002; 112:1281–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen-Tan PF, Le QT, Quivey JM, et al. Treatment results and prognostic factors of advanced T3–4 laryngeal carcinoma: the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and Stanford University Hospital (SUH) experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 50:1172–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porter MJ, McIvor NP, Morton RP, et al. Audit in the management of T3 fixed-cord laryngeal cancer. Am J Otolaryngol 1998; 19:360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson D, Robertson AG, Lamont D. A comparison of radiotherapy and surgery as primary treatment in the management of T3 N0 M0 glottic tumours. J Laryngol Oto 1993; 107:912–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones AS (1), Cook JA, Phillips DE, et al. Treatment of T3 carcinoma of the larynx by surgery or radiotherapy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1992; 17:433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryant GP, Poulsen MG, Tripcony L, et al. Treatment decisions in T3N0M0 glottic carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995; 31:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaves AL, Muniz F, Barbosa L, et al. Surgery followed by radiation therapy versus chemotherapy concurrent with radiation therapy for advanced larynx cancer: experience of a Brazilian community-based hospital. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2012; 269:1368. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Djordjevic V, Milovanovic J, Petrovic, et al. Radical surgery of the malignant laryngeal tumors. Acta Chir Iugosl 2004; 51:31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.2012; Fraser MA, Floyd E, et al. Treatment of laryngeal cancer at the brooklyn va. 147:187. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubben HH, Thames HD, Beck-Bornholdt HP, et al. Tumor volume: a basic and specific response predictor in radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 1998; 47:167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.