Abstract

The gate-keeping function of primary healthcare facilities has not been fully implemented in China. This study was aiming at assessing the willingness on community health centers (CHCs) as gatekeepers among a sample of patients and investigating the influencing factors.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in 2013. A total of 7761 patients aged 18 to 90 years from 8 CHCs in Shenzhen (China) were interviewed using a structured questionnaire. Descriptive and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to analyze the characteristics of patients, their willingness on the gatekeeper policy, and identify the associated factors.

On willingness of patients to select CHCs as gatekeepers, 70.03% of respondents were willing, 18.95% were neutral, and 9.02% were unwilling. Multivariable analysis indicated that female patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02–1.30); patients with health insurance (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.07–1.36); patients who lives near CHC (OR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.17–3.05); and patients who were more familiar with the gatekeeper policy (OR = 2.09, 95% CI: 1.85–2.36), had higher level of willingness on the policy. Conversely, reporting with good health status was independently associated with the decreased willingness on gatekeeper policy (OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.53–0.90).

The findings indicated that patients’ willingness on CHCs as gatekeepers is high. More priority measures, such as expanding medical insurance coverage of patients, strengthening the propaganda of gatekeeper policy, and increasing the access to community health service, are warranted to be taken. This will help to further improve the patients’ willingness on CHCs as gatekeepers. It is thus feasible to implement the gatekeeper policy among patients in China.

INTRODUCTION

The healthcare reform has been explored and investigated for many years in China. The latest round of nationwide systemic reform was launched in 2009,1 in which the importance of grading health care system was identified.

The gatekeeper policy, the central part of grading medical care, played a key role in setting up a well-structured and rationally functional healthcare delivery system, promoting appropriate use of health resources and managing the inappropriate increase of healthcare expenditures.2–5 The gatekeeper policy has been widely established in many western countries, such as Germany,6,7 Spain,8 the United Kingdom,9,10 and the Netherlands.11,12 In the last 5 years, China's healthcare reform has made substantial progress in expansion of the insurance coverage, and strengthening of the infrastructure of primary healthcare facilities.13 However, much effort is needed to improve the healthcare system. Specially, primary healthcare facilities have been unable to act as the gatekeepers in their functions and roles. The lack of the gatekeeper policy has become the greatest obstacle to the development of community health services (CHS). The unreasonable allocation of health resources, ambiguity of medical service, and the barriers to referrals between primary health institutions, secondary, and tertiary hospitals have been identified as challenges in China.13,14 The patients’ feeling and complaint of “too difficult and too expensive to see a doctor,” one of the key public policy issues, still exists.

Shenzhen was the first pilot city that initiated the gatekeeper policy, targeting migrant workers since 2006. However, the gatekeeper policy for the entire population or people with health insurance remains unestablished. Because the government worried about the patients’ willingness was low. Additionally, some developing countries also faced some difficulties to promote the gatekeeper policy. The same was faced by some developed countries in west in the last century. To promote the gatekeeper policy to the entire population, it was thus very essential to know the willingness of patients and necessary to identify the associated factors. The study aimed at characterizing demographic profiles of patients and identifying associated indicators determining the willingness of patients to accept the gatekeeper policy in a large-scale cross-sectional study in China. In light of Chinese healthcare reform, this study would not only inform policy makers about priority areas to promote the implementation and spreading of the gatekeeper policy in China, but also provide the valuable reference for other developing countries.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. All participants read a statement that explained the purpose of the survey and were provided with written consent form before participating in the study.

Data Sources and Sampling

The cross-sectional study was conducted between May 1, 2013 and July 28, 2013 in Bao’an district of Shenzhen, which is located in Guangdong Province (Southern China). A multistage random sampling method was performed in the study. First, 4 streets from Bao’an District were selected randomly. Second, 2 CHCs were randomly selected from every street. Third, 1000 outpatients from each CHC were randomly interviewed through self-administered anonymous questionnaires at the exit of the CHCs. All interviewers received adequate training to ensure the reliability of the survey.

Initially, 8000 patients were targeted at be recruited in the survey, of whom 80 (1%) refused to participate in the study. Additionally, 9 questionnaires were discarded because of a lot of missing data and logical error. Finally, 7911 eligible questionnaires remained, of which 7761 participants aged 18 years or older were included in the analysis.

Questionnaire Design and Content

Owing to the unavailability of validated questionnaires for this study, we designed a questionnaire based on literature review, group discussions, and mock interviews. Furthermore we conducted a pilot study at one of the CHCs to improve the quality of the questionnaire. The questionnaire included 3 parts: sociodemographic information, health status and health-seeking behavior, and awareness of the gatekeeper policy.

Measures

The dependent variable was the attitude of patients to the gatekeeper policy. The willingness on CHCs as gatekeepers was evaluated with 1 item (“Were you willing to consult the doctor initially at the CHC when you were sick, and if necessary, would be referred to the secondary or tertiary hospital by primary care physician.”). The question was closed-ended with 3 response options (agree, neutral, disagree). The independent variables covered sociodemographics characteristics (sex, age), socioeconomic status (education level, work status, and household monthly income per capita), health insurance status, self-reported health status, history of chronic diseases, frequency of CHS utilization over the past year, types of CHS utilization for this visit, the close medical institution in living area, and the familiarity with gatekeeper policy. Fifty percent of the average income was often assigned as the low-income line for the country or region internationally.15 However, in this study household monthly income per capital was estimated by low-income line for Shenzhen in 2012 classified in 4 categories: <1521¥ (low-income group), 1521¥–3041¥ (low- and middle-income group), 3042¥–6084¥ (middle- and high-income group), 6084+ ¥ (high-income group) respectively. Additionally, the type of CHS utilization was categorized into 2 groups: medical services (including disease diagnosis and treatment, purchasing medicines, and rehabilitation) and public health services (including health check, preventive care, and health education).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted for sociodemographics characteristics, socioeconomic factors, physical health status, history of chronic diseases, frequency of CHS utilization, types of CHS utilization, the close medical institution in your living area, and familiarity with the gatekeeper policy. χ2 tests were conducted to compare the acceptance of gatekeeper policy among different groups. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for factors that might be associated with the willingness of the gatekeeper policy, including neutral or disagreement attitude as the reference category. We used the stepwise selection method to select variables that were associated with patients’ willingness towards gatekeeper policy (level for selection and elimination: P = 0.05 and P = 0.10, respectively). In the multivariable model, independent variables included: age (18∼, 45∼, 60 + years), sex (female and male), marital status (single, widowed, divorced, married), education level (primary, junior, senior, college), working status (unemployment, employment, retire, other), household monthly income per capita (<1521¥, 1521¥–3041¥, 3042¥–6083¥, 6084+¥), health insurance (yes, no), self-perceived health status (good, fair, bad), history of chronic disease (yes, no), frequency of CHS utilization (1–2, 3–5, 6+ times a year) in the past year, types of CHS utilization (medical services, public health services), the close medical institution in their living area (private clinic or other, CHC, hospital), and the familiarity with gatekeeper policy (yes, no). All statistical analyses were performed by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 13.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, III), and all tests were 2-sided with a significance level of 0.05 except where otherwise specified.

RESULTS

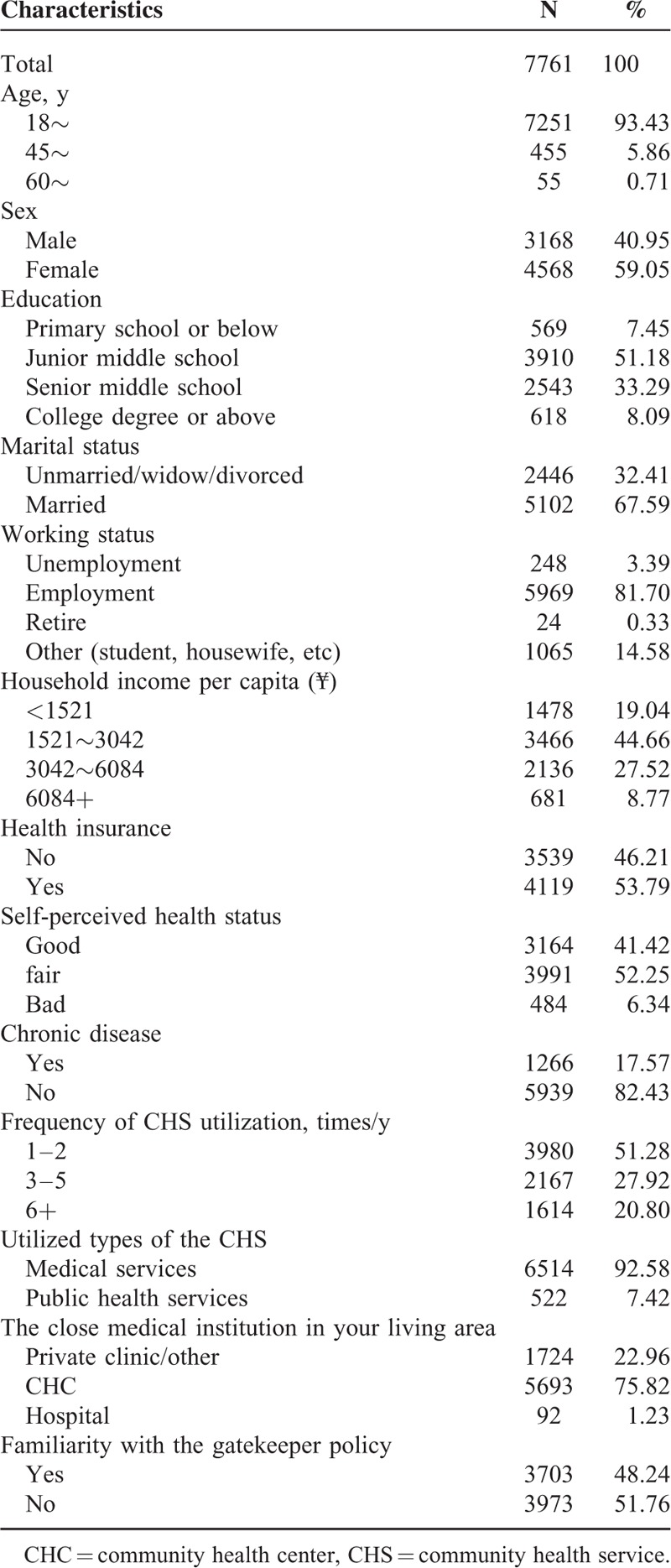

The main characteristics of participants were reported in Table 1. A total of 7,761 participants (4,568 females, 59.05%) were investigated in this study. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 90 years (mean age of 29.96 and standard deviation (SD) = 8.82). There were 58.63% of the participants who attended junior middle school or below. Most of the participants (63.70%) were from low and middle income groups. More than half of the participants (53.79%) were covered by health insurance plan. The 41.42% of participants reported to have a good self-perceived physical health status. On all the participants, the utilization of CHS was measured according to the frequency of CHS visits in the past year. The median of CHS visits was 2 times and the proportion of participants who had more than 6 times visits was 20.80%. The participants (92.58%) mostly utilized the medical services. The majority of respondents (75.82%) reported that the close medical institution in their living area was CHC, and more than half of respondents were unfamiliar with the gatekeeper policy (51.76%).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population

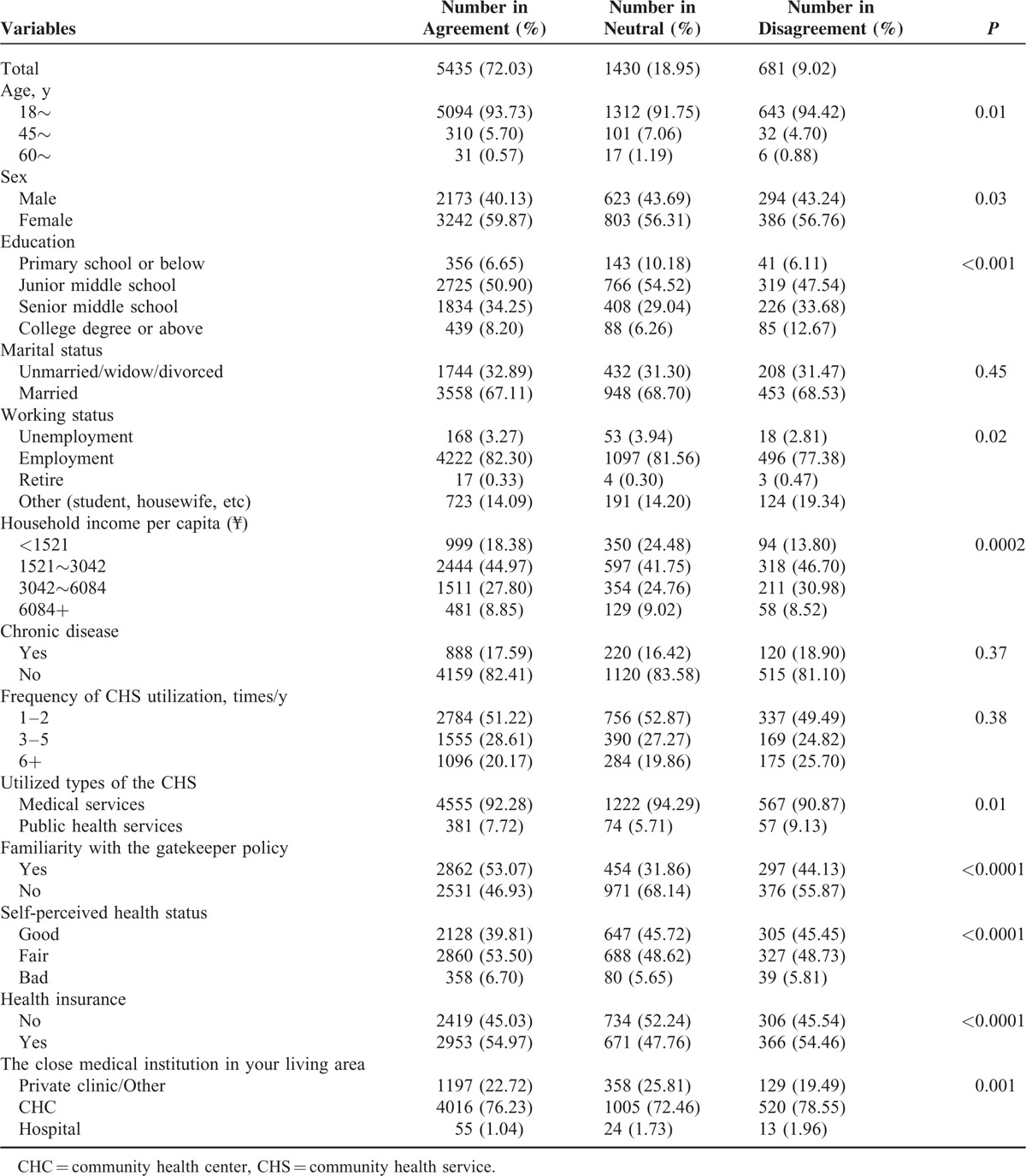

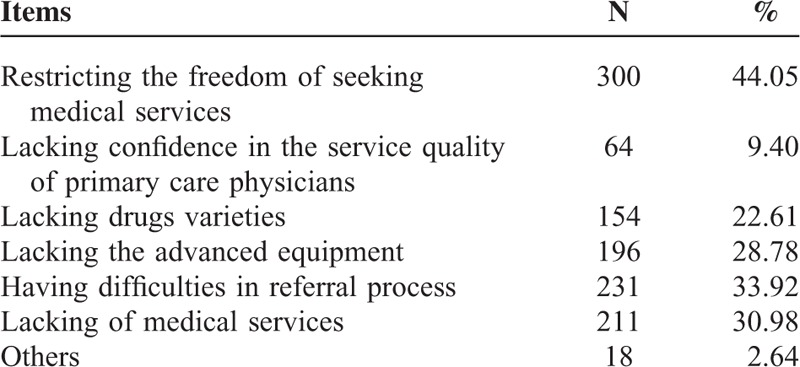

Pearson χ2 tests were used to assess the associations between characteristics of study population and willingness of participants toward the gatekeeper policy. The results are shown in Table 2. Overall, 72.03% of participants stated that they were willing to consult a doctor initially at CHCs when they were sick, and if necessary, they would get the referrals. There were significant differences in patients’ willingness of CHCs as gatekeepers in terms of age, sex, education level, working status, household monthly income per capita, health insurance, self-perceived health status, types of CHS utilization, the close medical institution in their living area, and familiarity with the gatekeeper policy (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Additionally, when we investigated the reasons for patients’ disagreement with the gatekeeper policy; restricting the freedom of seeking medical services and having difficulties in the referral processes were the 2 main reasons (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Factors Associated With the Acceptance of the Gatekeeper Policy Among Patients

TABLE 3.

Distribution According to the Reasons for Disagreement With Gatekeeper Policy Among Patients (N = 681)

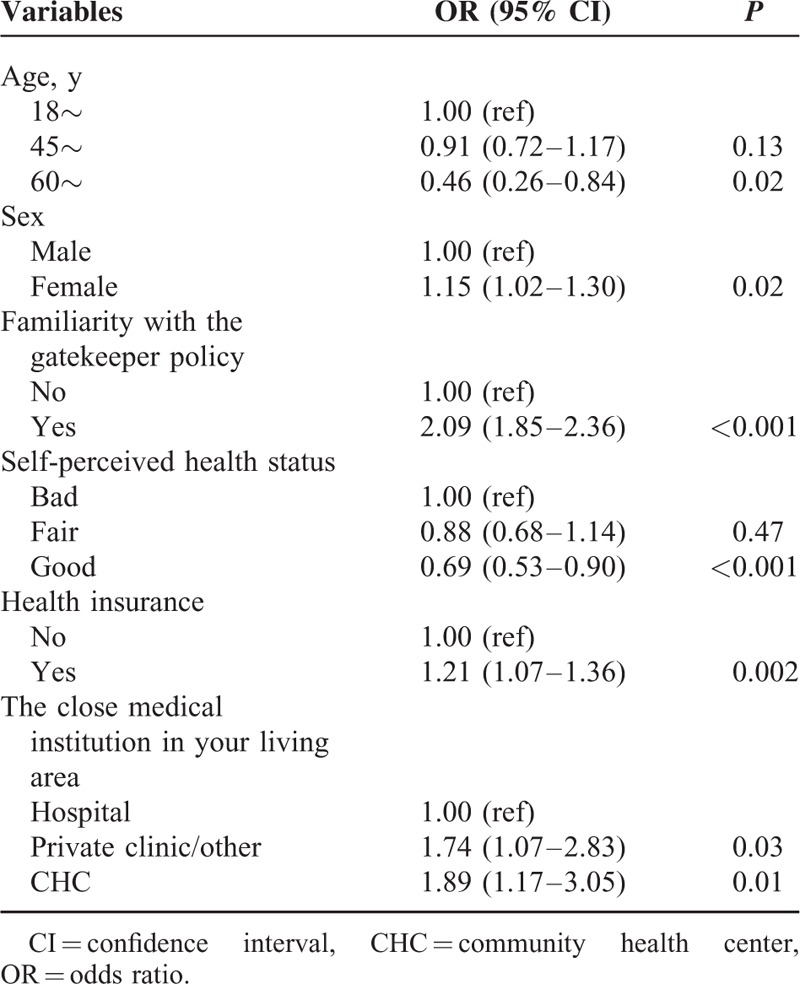

The factors associated with participants’ willingness were shown in Table 4. The results show that compared with males, females were more likely to agree on consulting the doctor first at CHC (OR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.02–1.30) when sick. Notably, the self-perceived health status was inversely associated with the participants’ willingness, and participants with good self-perceived health status were less willing to select CHCs as gatekeepers (OR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.53–0.90).

TABLE 4.

Logistic Regression Analysis for the Association With the Willingness of the Gatekeeper Policy Among Patients (N = 7546)

The association between health insurance and the willingness of gatekeeper policy was statistically significant. Participants with health insurance were more likely to accept the gatekeeper policy (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.07–1.36). In addition, participants with familiarity with the gatekeeper policy were more willing to select CHCs as gatekeepers (OR = 2.09, 95% CI 1.85–2.36). Finally, the nearest medical facilities from the patients living area was an important factor for the willingness of first-contact care. The participants who lived near by the CHCs were more likely to accept the gatekeeper policy than those who living near by the hospitals (OR = 1.89, 95%CI 1.17–3.05).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the willingness of gatekeeper policy and relevant determinants among patients in China, indicating that a majority of patients (72.03%) were willing to accept the gatekeeper policy, which showed that the CHS were highly acceptable by the public. The finding was much higher than previous studies conducted in other cities in China.16–19The willingness on CHCs as gatekeeper ranged from 40.0% to 95.5% in Israel,20 Germany,7 the United States,21 Canada,22 and the Netherlands.6The differences might result from the participants’ characteristics including age, sex, socioeconomic status, geographic regions, and sample size. Another possible explanation to this difference was that the gatekeeper policy for migrant workers was implemented in Shenzhen, which might promote the acceptance of patients to some extent.

The findings also showed that restricting the freedom of seeking medical services and having difficulties in the referral processes were the 2 main reasons for participants to refuse the gatekeeper policy, which needed to raise the attention to promote the gatekeeper policy from those health policy makers. Needless to say, conducting the reasonable idea of seeking care and emphasizing the value of primary care for the residents was a crucial strategy to improve the recognition for the gatekeeper policy. Additionally, on basis of the findings, we also suggest that optimizing the referral procedures and strengthening the care coordination between primary health care (PHC) facilities, secondary, and tertiary healthcare hospitals were also an important step to develop the China's 3-tier health system. The findings provided the crucial policy implications for the health and social security departments to determine the gatekeeper policy.

In this study, we obtained 2 important and interesting findings. First, the proportion of female visitors of CHCs was 59.05%, which was much higher than male. It identified that females were more likely to visit the CHCs when they needed health care services than males. These similar findings were reported in China (56.07%)23 and other countries such as UK (64.08%),24 Spain (53.20%),25 Australia (51.80),27 South Africa (66.60%),28 and Canada (65.00%).29 More importantly, the multivariable analyses indicated that sex was a significant indicator for the willingness to accept the gatekeeper policy among patients, and women were more likely to accept the gatekeeper policy. One possible explanation was that compared with male, female lived longer. However, paradoxically women reported greater morbidity and disability and made greater utilization of health care services.30–33 Another interpretation was that the different social construction of the disease (such as roles, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of females and males when they got sick or worried about the ill-health), which contributed to the different processes for seeking health care.26,30,33 In addition, women were more likely to seek the health services in PHC institutions because of low socioeconomic status.34 Second, the proportion of low- and middle-income groups was 63.70%. This study indicated that they were more likely to utilize the health care services. These results showed that the CHS might have important effect on provision of PHC services to meet the demands of vulnerable populations (eg, females and low-income groups). Additionally, the findings showed that CHCs of Shenzhen played an important role in promoting equity in health service utilization. In this regard, the results have shown that it was the right strategy for World Health Organization (WHO) in adopting primary healthcare to resolve the health care use for vulnerable populations.

There are significant association between medical insurance and the willingness of the gatekeeper policy among patients. The study showed that the participants with medical insurance were more likely to increase the probability of seeking care at CHC. The finding was consistent with previous studies.35,36 As such, it was thus necessary to make efforts to extend the medical insurance coverage, which would help to promote the gatekeeper policy. The findings raised an idea of combining initial consultations at CHC and medical insurance to ensure that general practitioners (GPs) serve as “gatekeepers” and patients are practically referred in to the healthcare system.37,38

The nearest medical facility of the patients’ living area was also an important predictor for the willingness of the gatekeeper policy. The participants who lived near CHC were more likely to accept the policy. In this study, 75.82% of participants reporting living near CHCs and were more frequent users of the CHS. In this study, distance to CHS was an important aspect in the availability of CHS. Therefore, the health department and related researchers should ensure that CHCs were strategically placed to guarantee the convenience in access to CHS to promote the gatekeeper policy.

In addition, this study indicated that participants with higher level of familiarity with the gatekeeper policy were more likely to accept the policy, which was consistent with previous study.16 It suggested that health administrators and other related departments should pay attention to strengthen the propaganda of the gatekeeper policy. Consequently, more announcements of the advantages, characteristics and the functions of CHCs would improve the public perception of CHS, which would be further favorable to improve the preference of the policy.

To the best of our knowledge, to date, this study is the largest cross-sectional study investigating the willingness of gatekeeper policy and relevant determinants among the patients in China. The large sample size significantly increased statistical power to detect social determinates of willingness of the gatekeeper policy. However, the generalizability of our data to other populations in China, particularly the elderly, other racial groups, and other poor regions, may be limited. In addition, all information was collected from a self-reported questionnaire and the response bias was therefore unavoidable. Finally, some other factors, such as the medical fees, relationship with doctors, waiting time, and satisfaction of participants were not considered, which might also be significant determinants of carrying out the gatekeeper policy of CHS.

CONCLUSION

Since the Chinese government worried that the patients’ willingness was low, the gatekeeper policy was not performed in China. Intriguingly, this study shows that the willingness is high among patients reported with health insurance, who were female, and who were familiar with gatekeeper policy. These findings remind the healthcare sector about the need to formulate more priority strategies for promoting the implementation of the gatekeeper policy in China.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Health Bureau of Bao’an district and community health centers for participating in the study. The authors also thank all study participants who have been involved and contributed to the procedure of data collection.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CHC = community health center, CHS = community health service, GP = general practitioner, OR = odds radio, PHC = primary health care, WHO = World Health Organization.

YG and WL contributed equally to this work.

This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 71373090, “Study on the gatekeeper policy of community health service”). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen Z. Launch of the health-care reform plan in China. Lancet 2009; 373:1322–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velasco Garrido M, Zentner A, Busse R. The effects of gatekeeping: a systematic review of the literature. Scand J Prim Health Care 2011; 29:28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kravitz RL. Beyond gatekeeping: enlisting patients as agents for quality and cost-containment. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23:1722–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starfield B, Powe NR, Weiner JR, et al. Costs vs quality in different types of primary care settings. JAMA 1994; 272:1903–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zentner A, Velasco Garrido M, Busse R. Do primary care physicians acting as gatekeepers really improve health outcomes and decrease costs? A systematic review of the concept gatekeeping. Gesundheitswesen 2010; 72:e38–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linden M, Gothe H, Ormel J. Pathways to care and psychological problems of general practice patients in a “gate keeper” and an “open access” health care system: a comparison of Germany and the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003; 38:690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Himmel W, Dieterich A, Kochen MM. Will German patients accept their family physician as a gatekeeper? J Gen Intern Med 2000; 15:496–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez Aurrecoechea B, Valdivia Jimenez C. [Primary care pediatrics in the public health system of the twenty-first century. SESPAS report 2012]. Gac Sanit 2012; 26 Suppl 1:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McEvoy P, Richards D. Gatekeeping access to community mental health teams: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2007; 44:387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gervas J, Perez Fernandez M, Starfield BH. Primary care, financing and gatekeeping in western Europe. Fam Pract 1994; 11:307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens FC, van der Horst F, Hendrikse F. The gatekeeper in vision care. An analysis of the co-ordination of professional services in The Netherlands. Health Policy 2002; 60:285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schafer W, Kroneman M, Boerma W, et al. The Netherlands: health system review. Health Syst Transit 2010; 12:1–228.v-xxvii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yip W, Hsiao W. Harnessing the privatisation of China's fragmented health-care delivery. Lancet 2014; 384:805–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu S, Tang S, Liu Y, et al. Reform of how health care is paid for in China: challenges and opportunities. Lancet 2008; 372:1846–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mo TJ. The poverty and social security of Hong Kong. 1993; Hong Kong: Zhong Hua Book Company, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie Y, Dai T, Zhu K, et al. Analysis of residents’ willingness to select community doctor as gatekeeper and its determinats. Chinese Gen Practs 2010; 13:1621–1623. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao W, Lin Y, Zhong W, et al. A study on the willingness of first-contact care among the residents in Guangdong. Soft Sci Health 2014; 28:602–606. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian G, Wang G, Jin S, et al. Analysis of outpatients’ willingness to accept the first treatment in the community of Zhabei district of Shanghai. Chinese Health Res 2014; 17:241–243. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin X, Zhang K, Hu D, et al. Analysis of residents’ willingness to seek first contact in community health organizations in Jiansu Province. Chinese Hosp Manag 2007; i27:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross R, Tabenkin H, Brammli-Greenberg S. Who needs a gatekeeper? Patients’ views of the role of the primary care physician. Fam Pract 2000; 17:222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grumbach K, Selby JV, Damberg C, et al. Resolving the gatekeeper conundrum: what patients value in primary care and referrals to specialists. JAMA 1999; 282:261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steele LS, Glazier RH, Agha M, et al. The gatekeeper system and disparities in use of psychiatric care by neighbourhood education level: results of a nine-year cohort study in toronto. Healthc Policy 2009; 4:e133–e150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong X, Liu L, Cao S, et al. Focus on vulnerable populations and promoting equity in health service utilization--an analysis of visitor characteristics and service utilization of the Chinese community health service. BMC Public Health 2014; 14:503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, et al. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract 2000; 49:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palacios-Cena D, Hernandez-Barrera V, Jimenez-Garcia R, et al. Has the prevalence of health care services use increased over the last decade (2001–2009) in elderly people? A Spanish population-based survey. Maturitas 2013; 76:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redondo-Sendino A, Guallar-Castillon P, Banegas JR, et al. Gender differences in the utilization of health-care services among the older adult population of Spain. BMC Public Health 2006; 6:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parslow R, Jorm A, Christensen H, et al. Gender differences in factors affecting use of health services: an analysis of a community study of middle-aged and older Australians. Soc Sci Med 19822004; 59:2121–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mash B, Fairall L, Adejayan O, et al. A morbidity survey of South African primary care. PloS One 2012; 7:e32358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Tuna M, et al. Age equity in different models of primary care practice in Ontario. Canad Fam Physician 2011; 57:1300–1309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macintyre S, Hunt K, Sweeting H. Gender differences in health: are things really as simple as they seem? Soc Sci Med 19821996; 42:617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verbrugge LM. Gender and health: an update on hypotheses and evidence. J Health Soc Behav 1985; 26:156–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez-Mayoralas G, Rodriguez V, Rojo F. Health services accessibility among Spanish elderly. Soc Sci Med (1982) 2000; 50:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leon-Munoz LM, Lopez-Garcia E, Graciani A, et al. Functional status and use of health care services: longitudinal study on the older adult population in Spain. Maturitas 2007; 58:377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ladwig KH, Marten-Mittag B, Formanek B, et al. Gender differences of symptom reporting and medical health care utilization in the German population. Eur J Epidemiol 2000; 16:511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng SH, Chiang TL. Disparity of medical care utilization among different health insurance schemes in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med (1982) 1998; 47:613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong Y, Yin X, Wang Y, et al. Social determinants of community health services utilization among the users in China: a 4-year cross-sectional study. PloS One 2014; 9:e98095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang HH, Wong SY, Wong MC, et al. Patients’ experiences in different models of community health centers in southern China. Ann Fam Med 2013; 11:517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang H, Huang X, Zhou Z, et al. Determinants of Initial Utilization of Community Healthcare Services among Patients with Major Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases in South China. PloS One 2014; 9:e116051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]