Abstract

The aim of this study was to add a new case of primary non-Hodgkin's malignant lymphoma of the vulva to the literature and to review the current literature.

We searched the PubMed/MEDLINE databases for previous case reports using the key words “non-Hodgkin's malignant lymphoma of the vulva,” “vulvar lymphoma,” and “primary vulvar non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.” We found 29 cases of primary vulvar non-Hodgkin's malignant lymphoma of the vulva reported until 2015. Among them, only 8 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), classified according to the most recent 2008 WHO classification, were reported.

Moreover, only few studies reported the therapeutic management and clinical follow-up of patients affected by this condition.

Due to its uncommon presentation, the primary non-Hodgkin's malignant lymphoma of the vulva can be undiagnosed; thus gynecologists, oncologists, and pathologists should be aware of this condition, as a correct diagnosis is essential for an appropriate therapeutic management.

INTRODUCTION

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) may involve the gynecological tract in the 30% of cases, most often as a manifestation of systemic disease.1 In order of frequency, ovary (49%), uterus (29%), Fallopian tubes (11%), vagina (7%), and vulva (4%) can be involved.2

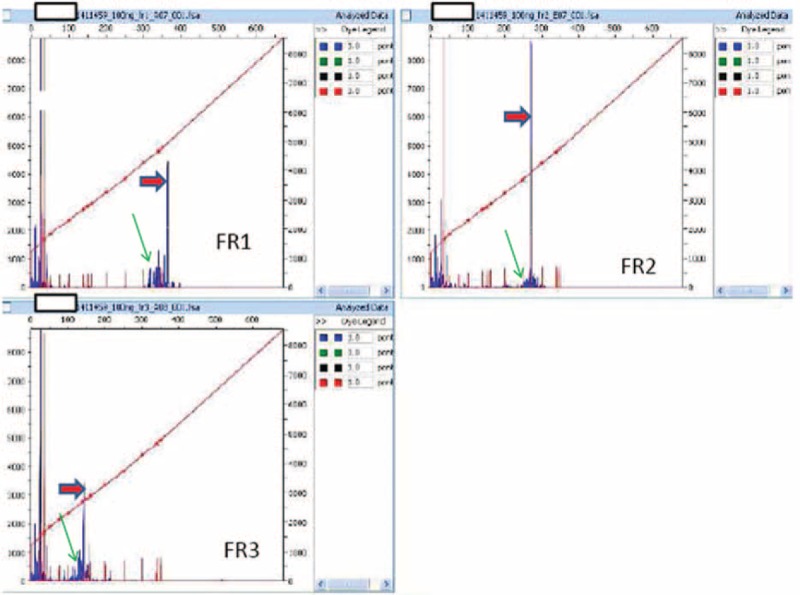

Therefore, vulvar NHL is quite rare and only very few cases of primary NHL involving the vulva have been reported in the literature (Table 1); thus it often poses a diagnostic challenge if its existence is not suspected.3

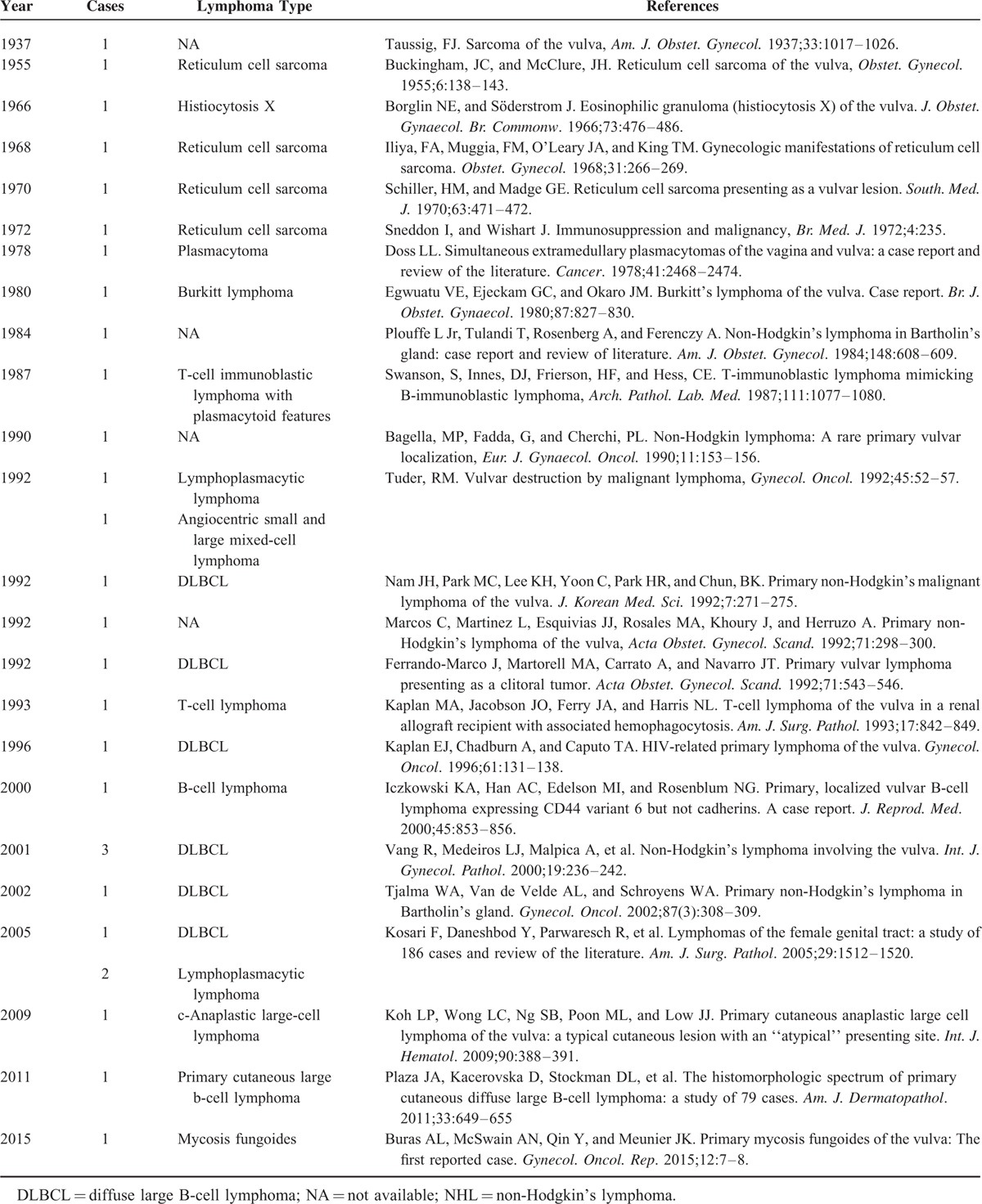

TABLE 1.

Primary NHL of the Vulva Reported in Literature

Vulvar NHL may present as a localized, solid, nontender mass confined to the clitoris or Bartholin's glands4; less often it can spread within the subcutaneous fibroadipose tissue of the labia maiora.5

We report the case of a woman diagnosed with a primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the upper part of the left labium maior of the vulva, arising in a background of a persistent lymphoma-like lesion (pseudolymphoma) of the inguino-femoral region diagnosed 1 year previously.

The uncommon presenting site of this entity warrants great diagnostic accuracy because of its prognostic and therapeutic implications.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old woman presented to our Institution with a 6 months history of a nontender mass in the upper part of the left labium maior. She was nulliparous and a moderate tobacco user (5–6 cigarettes/day).

One year earlier, the patient had developed a solid nontender mass within the left inguino femoral region. She underwent surgery in another Institution and a fibroadipose mass of 6.5 × 4.5 × 3.8 cm was excised. The mass had sclerotic areas and blood vessels in the context of friable fibroadipose tissue, with lymphocyte infiltration. The diagnosis was subcutaneous pseudolymphoma.

When the woman presented to our Institution, a gynecological examination was performed and revealed a solid mass of ∼3 cm, with irregular margins, in the upper third of the left labium maior. This mass was movable and nontender. A recurrence of the subcutaneous pseudolymphoma previously diagnosed was observed in the left inguino femoral region. The vagina and anal sphincter were clear of disease. The pelvic examination revealed normal cervix and vagina, and uterus of normal size with no palpable adnexal masses. Routine laboratory tests were normal. An abdominal CT scan with contrast revealed a left inguino-femoral adenopathy and a solid mass, without specific acquisition of contrast, within the left vulvar region. No hepatosplenomegaly was detected. Thus we decided to excise the vulvar mass to get an accurate histopathologic diagnosis of the lesion.

Wide local excision, with 1 cm clear peripheral margins, was performed. The mass was 3.2 cm in the maximum diameter and the cut surface showed a multilobular soft mass of whitish color, without necrosis or hemorrhage.

The histological examination (Figure 1A and B) showed a diffuse population of medium- to large-sized malignant lymphoid cells, which displayed vescicular and irregular nuclei with up to 4 membrane-bound nucleoli. Mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies were evident, as well as an admixed inflammatory infiltrate, mainly consisting of neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes.

FIGURE 1.

Immunohistological findings. The lesion showed a diffuse malignant lymphoid population of medium- to large-sized cells, which displayed vescicular and irregular nuclei with evident nucleoli (A, B: Hematoxylin & Eosin, C: diffuse immunopositivity for CD20; D: positive staining for BCL6; E: positive staining for CD10; F: positive staining for ICSAT/MUM1).

2.5-micron sections were cut and immunohistochemical analysis was performed in an automated system (Benchmark-XT, Ventana, Tucson, AZ). Neoplastic cells were positive for the following antibodies (Figure 1B–F):

CD20 (monoclonal, clone L26, dilution 1:200, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark)

CD10 (monoclonal, clone SP67, prediluted, Ventana, Tucson, AZ)

BCL-2 (monoclonal, clone 124, prediluted, Ventana, Tucson, AZ)

CD30 (monoclonal, clone berH2, prediluted, Ventana, Tucson, AZ)

ki67 (40%) (monoclonal, clone 30.9, prediluted, Ventana, Tucson, AZ)

BCL-6 (monoclonal, clone G/191E/A8, prediluted, Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA)

ICSAT (Interferon Consensus Sequencebinding protein for Activated T cells)/MUM1 (multiple myeloma oncogene 1) (polyclonal, dilution 1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX).

Neoplastic lymphoid cells did not react with the following antibodies: CD3 (monoclonal, 2GV6, prediluted, Ventana), CD5 (monoclonal, clone 4C7, dilution 1:100, Novocastra-Leica biosystems, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK), ALK-1 (monoclonal, clone ALK01, prediluted, Ventana).

The final pathologic diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). According to the immunohistochemical markers expressed, this DLBCL belonged to the subgroup with germinal center B cell-like (GCB) profile, which has shown a better prognosis compared with non GCB-like lymphomas.6 The definition of primary lymphoma was given, according to criteria adopted by Kosari et al.7 Molecular analysis further demonstrated the monoclonal origin of the lesion (Figure 2).

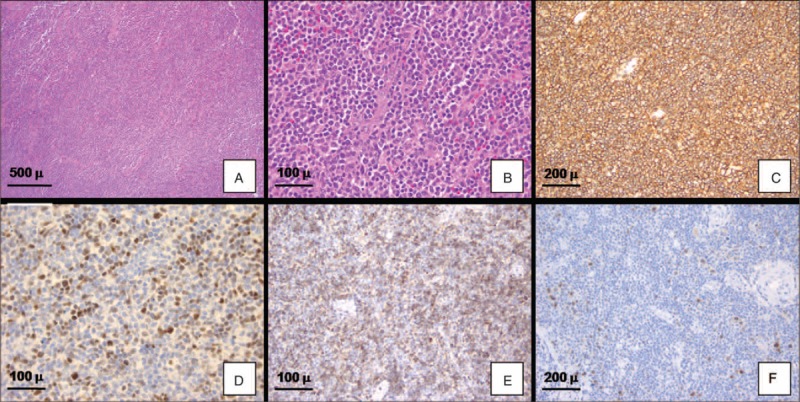

FIGURE 2.

B-cell clonality determination using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and capillary electrophoresis (GENESCAN analysis). Analysis of 3 different PCRs carried out using primers for FR1, FR2, FR3 regions (forward primer), and JH region (reverse primer): a single band consistent with single monoallelic clonal rearrangement is indicated by a red arrow; polyclonal background is indicated by a green arrow. JH = joining region of heavy chain; PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

At the time of diagnosis, the patient had no constitutional symptoms and the laboratory data were as follows: serum lactate dehydrogenase was 255 U/L (230–460 U/L); serum β2 microglobin was 1.49 mg/L (0.8–2.40 μg/mL). The blood routine examination and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate were normal. Urine occult blood was negative. Urea was 31 mg/dL (10–50 mg/dL), uric acid was 3.5 mg/dL (2.40–6.00 mg/dL). Serologic evaluations of HCV, HBV, and HIV infection were negative. K and lambda free chain ratio was normal.

The PET-CT performed 40 days after the vulvar excisional surgery showed a mass in the left inguinal area (>5 cm, bulk), and a smaller one (2 cm) in a right inguinal node with elevated 18-FDG activity, which did not undergo surgical excision. The PET-CT showed a positive 2 cm mass in the left breast that was biopsied and diagnosed as fibroadenoma.

Moreover, a staging bone marrow biopsy in the iliac crest was then performed and resulted negative for neoplasia.

In conclusion the patient had a stage IIE disease, according to revised staging for primary nodal lymphoma and Lugano classification.8 Regarding the prognostic factors we considered an aa-IPI 0 (low risk) and MInT unfavorable subgroup (>5 cm).9,10

Due to the MInT unfavorable group and the age, the patient underwent to R-CHOP chemotherapy (rituximab 375 mg/m2 i.v. day 1, Endoxan 750 mg/m2 i.v. day 2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 i.v. day 2, and prednisone 100 mg from day 2 to day 6 every 14 days for 6 cycles) without consolidation radiotherapy considering the fast achievement of complete response after 2 cycles of treatment assessed with PET-CT scan.

The treatment was well tolerated with the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for 6 days from day 4 from the beginning of the chemotherapy. Prophylaxis with fluconazole 100 mg a day, cotrimoxazole 1 tablet a day, and acyclovir 800 mg a day were also administered.

At the first follow-up visit, 6 months after the end of chemotherapy, the patient showed a complete remission of the disease, without clinical signs or symptoms and no pathological findings on PET-CT scan; the routine laboratory tests were normal.

A signed written consent was obtained from the patient for this case report.

DISCUSSION

Primary vulvar NHL is a rare entity and, as such, has been reported only in single cases and in few limited series, most of which lacked a detailed immunohistochemical analyses and molecular tests (which often were not available at the time of diagnosis) and used out-dated classifications. Moreover, sometimes authors used archaic terminology, that is, “reticulum cell sarcoma” or “lymphosarcoma”: those cases are now hypothesized to represent DLBCL, according to the most recent classification.11 Furthermore, only few previous studies reported the therapeutic management and the clinical follow-up of patients affected by this condition.

Until 2015, 29 cases of primary vulvar non-Hodgkin's malignant lymphoma were reported (Table 1): among them only 8 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), classified according to the most recent 2008 WHO classification, were identified. Moreover, only 3 cases of vulvar pseudolymphoma (lymphoma-like) have been reported, only 1 of which evolving into lymphoma of the vulva.4,12,13

There is increasing evidence that these tumors may have been underdiagnosed by either the gynecologists (because of their low incidence and unusual site of presentation) or by the pathologists (because they could be mistaken for different malignancies or for inflammatory lesions).

The differential diagnosis of vulvar NHL includes inflammatory conditions (e.g., lichenoid dermatoses, lymphoma-like lesions), carcinomas (e.g., neuroendocrine carcinomas, Merkel's cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma or cutaneous adnexa carcinoma), Hodgkin lymphoma and lesions with small round blue cell or sarcomatoid components (e.g., melanoma, extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor). Reactive processes are usually superficial, band-like, noninfiltrating and they are commonly composed of a polymorphous population of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes without atypia.1,4

Poorly differentiated epithelial tumors may have a broad, discohesive pattern that might mimic DLBCL. However, focal intercellular bridges, keratinization and the association with an in situ component, are all clues to the diagnosis of an epithelial neoplasm. On the contrary, sclerosis that compartimentalizes neoplastic lymphoid cells in DLBCL may be mistaken for cluster and cords of a carcinoma. Immunohistochemical stains and, when needed, molecular tests are of invaluable help in making this distinction.1,4

The most used treatment for vulvar lymphoma is actually R-CHOP therapy, with or without consolidation radiotherapy.14 Recently, however, several studies have demonstrated that the cell of origin of DLBCL is of particular clinical relevance. Indeed, the distinction between Activated B Cell (ABC) and Germinal Centre B Cell (GBC) DLBCLs is not only important from a scientific point of view, but also has clinical implications, as these subtypes are characterized by differences in the overall survival when treated with the standard treatment of rituximab and CHOP chemotherapy (R-CHOP). The majority of patients diagnosed with GCB-DLBCL respond favorably to R-CHOP, whereas R-CHOP appear to be less effective in ABC-DLBCL patients.15 For these reasons, we treated this case of vulvar lymphoma, derived from GCB, with the standard R-CHOP.16 Even if in previous studies the dose intensification of R-CHOP by a 14-day versus a 21-day cycle did not result in improved outcomes,17 for this young patient, we preferred the 14-day R-CHOP taking into account the faster conclusion of the treatment. With the rapid achievement of a complete response after 2 cycles that was confirmed with PET-CT scan after 6 courses of R-CHOP, we chose to avoid radiotherapy, according to RICOVER-North study in which overall survival benefit was not demonstrated.18

CONCLUSION

The aim of this case report was to highlight an unusual and extremely rare case of vulvar disease.

Primary vulvar NHL is a rare entity; thus it often poses a diagnostic challenge if its existence is not suspected. Gynecologists, oncologists, and pathologists should be aware of this condition, as a correct diagnosis is essential for an appropriate therapeutic management. These patients should always be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team with particular expertise in NHL.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ABC = activated B cell, CT = computed tomography, DLBCL = diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, GCB = germinal center B cell, G-CSF = Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor, NHL = non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, PET = positron emission tomography

NC and LA contributed equally to this study.

Authors’ contribution—study concept and design: NC, FS; acquisition of data: NC, LA, MR, PB, EL; analysis and interpretation of data: NC, LA, MR, FS; drafting of the manuscript: NC, LA, MR; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: FS, VC.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vang R, Medeiros LJ, Malpica A, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma involving the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000; 19:236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagella MP, Fadda G, Cherchi PL. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a rare primary vulvar localization. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1990; 11:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koh LP, Wong LC, Ng SB, et al. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the vulva: a typical cutaneous lesion with an ’atypical’ presenting site. Int J Hematol 2009; 90:388–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagoo AS, Robboy SJ. Lymphoma of the female genital tract: current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006; 25:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nam JH, Park MC, Lee KH, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin's malignant lymphoma of the vulva—a case report. J Korean Med Sci 1992; 7:271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004; 103:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosari F, Daneshbod Y, Parwaresch R, et al. Lymphomas of the female genital tract: a study of 186 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29:1512–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Alliance, Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Consortium; Italian Lymphoma Foundation; European Organisation for Research; Treatment of Cancer/Dutch Hemato-Oncology Group; Grupo Español de Médula Ósea; German High-Grade Lymphoma Study Group; German Hodgkin's Study Group; Japanese Lymphorra Study Group; Lymphoma Study Association; NCIC Clinical Trials Group; Nordic Lymphoma Study Group; Southwest Oncology Group; United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32:3059–3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Osterborg A, et al. MabThera International Trial Group. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7:379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. World Health Organization classification of tumours of haematopoietic and Lymphoid tissues, fourth edition. Lyon:International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Orelli S, Schnarwyler B, Maurer R, et al. Vulvar pseudolymphoma: detection of infection by Borrelia burgdorferi using polymerase chain reaction. Gynakol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch 1998; 38:143–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martorell M, Gaona Morales JJ, Garcia JA, et al. Transformation of vulvar pseudolymphoma (lymphoma-like lesion) into a marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of labium majus. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008; 34:699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Kacemi H, Lalya I, Kebdani T, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the vulva in an immunocompetent patient. J Cancer Res Ther 2015; 11:657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenz G. Insights into the molecular pathogenesis of activated B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and its therapeutic implications. Cancers (Basel) 2015; 7:811–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coiffier B. State-of-the-art therapeutics: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:6387–6393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham D, Hawkes EA, Jack A, et al. Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone in patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a phase 3 comparison of dose intensification with 14-day versus 21-day cycles. Lancet 2013; 381:1817–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Held G, Murawski N, Ziepert M, et al. Role of radiotherapy to bulky disease in elderly patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32:1112–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]