Abstract

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with a complex pathogenesis, where changes in skin barrier and imbalance of the immune system are relevant factors. The skin forms a mechanic and immune barrier, regulating water loss from the internal to the external environment, and protecting the individual from external aggressions, such as microorganisms, ultraviolet radiation and physical trauma. Main components of the skin barrier are located in the outer layers of the epidermis (such as filaggrin), the proteins that form the tight junction (TJ) and components of the innate immune system. Recent data involving skin barrier reveal new information regarding its structure and its role in the mechanic-immunological defense; atopic dermatitis (AD) is an example of a disease related to dysfunctions associated with this complex.

Keywords: Antimicrobial cationic peptides; Claudins; Dermatitis, atopic; Immunity, innate

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a highly prevalent dermatosis in the population, especially in children. It has a chronic, inflammatory and pruriginous nature and progresses with periods of exacerbation. Its increasing prevalence in recent decad ranges from 10% to 20% in children and reaches 3% in adults. 1,2 AD can be associated with other manifestations of atopic disease such as asthma and rhinitis, which occur more frequently in patients with recalcitrant AD.1

For many years, the altered immune response in AD has been considered the main mechanism for inflammation and changes in skin permeability (inside-ouside theory). However, the outside-inside theory was then conceived, and the skin barrier defects in AD proved to exert a key role in the pathogenesis of AD.3,4

This review aims to focus on dysfunction of proteins of the skin barrier (filaggrin and claudins 1 and 4) and of components of the innate immune system (pattern recognition receptors, secretory elements, predominant cells of the innate immune system and skin microbiota) in AD patients, which contribute to the constant AD phenotype of xerosis, inflammation and susceptibility to infections.

SKIN BARRIER

Protection and defense are the main functions of the skin. Regulation of the transepidermal water loss (TEWL), defense against the action of external physico-chemical agents and aggression of microorganisms are part of the skin barrier. The stratum corneum (SC) is the main component of such barrier, and is based on the "brick and mortar" structure. Its filmogenic feature is due to the association of SC with surface lipids.5

Filaggrin and proteins of the tight junctions (TJs) have been the most studied components of the skin barrier. Filaggrin, after hydrolyzed, contributes to the formation of relevant components for pH maintenance, moisture and skin protection against microbial agents. TJ protein with active expression, on the other hand, are important to control the selective permeability of the epidermis to build the barrier against the external environment, therefore promoting recognition of the cell "territory".6

Skin barrier proteins with functional relevance

Filaggrin

Filaggrin is a protein originated from pro-filaggrin, produced by keratinocytes. It is the main component of keratohyalin granules, visualized by light microscopy within the granular layer. Conversion of pro-filaggrin into filaggrin, both intracellular proteins, occurs through dephosphorylation and proteolysis by serine proteases, releasing multiple active monomers of filaggrin.7 With the decrease of the water gradient in the outer layers of the epidermis, filaggrin hydrolysis occurs in hygroscopic amino acids.8,9 Factors such as age, ultraviolet B radiation, relative humidity and hypoxia affect this process.10,11

Hygroscopic amino acids, especially arginine, glutamine and histidine are detected within the intercellular space.10 They generate the natural moisturizing factors (NMF), responsible for the maintenance of SC and pH hydration for the production of urocanic acid (UCA) in its cis and trans forms, as well as 5- pyrrolidone carboxylic acid (PCA).10,12,13 Furthermore, these two byproducts filaggrin have inhibitory effects on the Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) growth.14

Changes in barrier proteins, such as decreased expression of filaggrin in the skin, and mutations with loss of function in filaggrin gene (FLG), such as those found in ichthyosis vulgaris, have been described in AD.10,15 These mutations lead to increased risk of early onset of the disease, respiratory atopy, allergies, elevated IgE serum levels and persistence of AD in adulthood.16 Moreover, there is a significant relationship between AD with FLG mutation and peanut allergy mediated by IgE, indicating an increased skin permeability and consequent enhanced exposure to allergens.17

Interleukins (IL) 4 and 13, detected in AD lesions, also lead to decreased expression of filaggrin in keratinocytes.18 The family of IL-1 has relevant pro-inflammatory features, such as IL-1α, suggesting that the onset of inflammation may occur due to changes in the skin barrier. Morevoer, there are reports of decrease of NMF in the SC of individuals with AD and mutations in the FLG gene, with increase of IL-1 family cytokines in non-inflammed skin.19

Therefore, patients with AD and deficiency in FLG expression have decreased SC hydration, increased TEWL, and higher pH than non-atopic individuals, with an augmented risk of developing allergies, asthma and rhinitis.20 Changes in the skin barrier due to filaggrin deficiency may also lead to inflammation, and reduced protein expression in keratinocytes (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

Key topics on filaggrin

| ATOPIC DERMATITIS AND FILAGGRIN: |

|---|

| • Filaggrin gene (FLG) mutation |

| • Decreased filaggrin expression: |

| • higher risk of early onset of the disease |

| • persistence of atopic dermatitis in adulthood |

| • increased risk of allergies by percutaneous sensitization |

| • association with high serum levels of IgE and other manifestations of atopy |

Tight junctions

TJ are formed by a complex of transmembrane and intracellular proteins found in simple and stratified mammalian epithelia. In normal skin, they are detected in the granular layer, and its expression rapidly increases after injury. They are essential for cell differentiation and keratinization of epidermal cells.6 In skin diseases with altered keratinization, such as psoriasis and ichthyosis vulgaris, they are present even in the deeper layers of the epidermis.21

TJ play an important role in epidermal selective permeability, controlling intercellular flow of substances such as hormones, cytokines and electrolytes, functioning as "gates". This permeability depends directly on the size and ionic specificity of the molecule. In addition to the intercellular permeability function, these structures also act as markers of the cell "territory".22

The intracellular portion of TJ binds to cytoskeletal plasma proteins, while the extracellular portion forms a "loop" in the intercellular space, connecting with the adjacent cell loop. TJ are formed by occludin, claudin, zonula occludens 1 (ZO1) and 2 (ZO2), junctional adhesion molecule-1 (JAM1) and the multi-PDZ-1 protein (MUPP1).23

In 2002, Tsukita and Furuse showed that claudin 1 deficiency in mice led to high TEWL and liver abnormalities, culminating with death.22 These animals showed no structural abnormalitie, but significant loss of function of the skin barrier. A similar clinical condition of claudin 1 deficiency was described in human neonates (ichthyosis-sclerosis-cholangitis syndrome).24

TJ proteins also play an important role in the invasion of some viruses (e.g.: herpes simplex) and bacteria. Some of these organisms use claudin 1 as receptors; others modulate the structure of TJ, inserting effectors, activating signals or even directly connecting to them, resulting in their partial break.25,26 Its expression rapidly increases via activation of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2).27

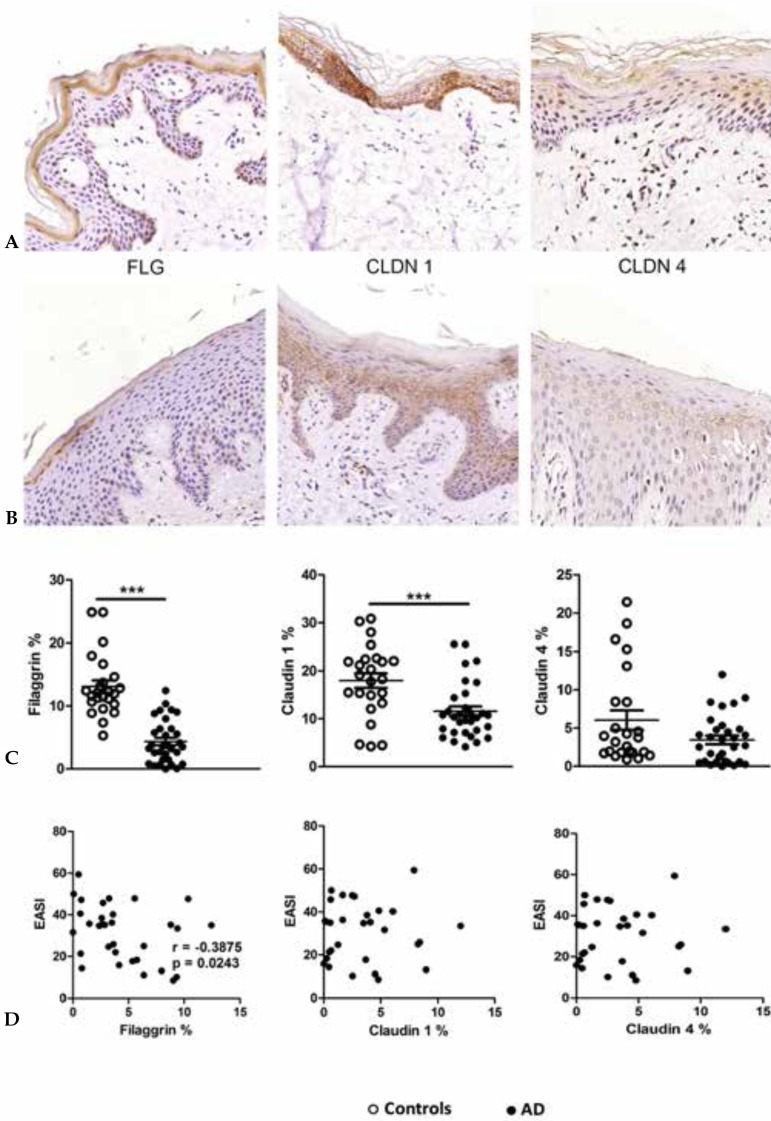

The lesional skin of atopic patients contains significant decreased claudin 1 expression, but no claudin 4 reduction, when compared to the skin of non-atopic individuals (Figure 1).28-30 Reduced claudin 1 appears to be related to increased risk of infection by herpes virus type 1 (HSV1) in individuals with AD.25 There is also an inverse relation between the expression of claudin 1 and the presence of the immune response markers Th2, suggesting that this protein affects the immune response to potential environmental allergens (Chart 2).28

Figure 1.

Expression of filaggrin (FLG), claudin 1 (CLDN1) and claudin 4 (CLDN4) in skin fragments of adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) stained by immunohistochemistry. (A) Skin fragments of healthy controls: FLG, CLDN1 and CLDN4. (B) Skin fragments of patients with AD, showing reduced expression of FLG, CLDN1 and CLDN4. (C) Expression of FLG, CLDN1 and CLDN 4 (area percentage) in the control group without AD (n=33) compared with patients with AD (n=25). (D) Correlation between disease severity (EASI) and the expression of the proteins in the skin barrier. The line represents the arithmetic mean of the expression of proteins in the skin barrier (percentage area). ** p≤0.01 and *** p≤0.001

Adapted from Batista, et al. 2015.29

Chart 2.

Key topics on tight junctions

| ATOPIC DERMATITIS AND TIGHT JUNCTIONS: |

|---|

| • Decreased expression on the skin without injury |

| • Favors infection by herpes-virus type 1 and other viral skin infections |

| • Increased paracellular permeability |

| • Increased risk of allergy to large molecules |

| • Proteins with active expression: |

| • Increase with activation via Toll-like receptor 2 |

| • Decrease with increased Th2 citokynes |

Innate immune system

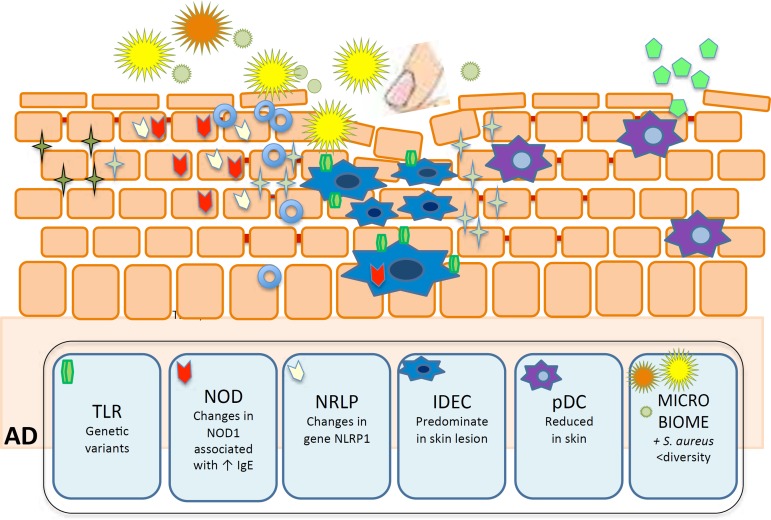

The innate immune system represents the initial and non-specific response of the human body to external aggressions. This response does not derive or result from target-oriented immune memory, but has an essential role in protecting the individual against potential pathogens. An intact skin barrier is needed, with proper maintenance of its cycle, pH and microbiota. Other componenents of such defense system includes secretory elements, cell receptors, such as pattern recognition receptors (PRR), immune cells and the skin microbiota (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Main components of innate immune system in epidermis and their role

in atopic dermatitis (AD). Defects in Toll-like receptor 2

contribute to increased colonization and infection by S. aureus.

Decreased AD expression of AMP (catelicidin-LL37 and

β-defensin) also favors skin infections. Reduced plasmacytoid

dendritic cells in skin injured areas by AD, facilitating certain

viral skin infections. Reduced NK cells in AD. S. epidermidis

increase the expression of human β-defensin by human

keratinocytes through TLR2 signaling pathway. IDEC are increased in

AD skin lesion. NOD1 changes are associated with elevated IgE levels

in AD individuals. Changes in expression of NLRP1 gene were

associated to AD severity  Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus),

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus),  Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis),

Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis),

other

bacteria,

other

bacteria,  staphylococcal enterotox in,

staphylococcal enterotox in,  virus,

virus,  Toll-like receptors (TLR),

Toll-like receptors (TLR),  nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing

protein (NOD)

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing

protein (NOD)  NOD-like receptor protein (NLRP)

NOD-like receptor protein (NLRP)  β-defensina 1,

β-defensina 1,

HBD-2,3 e

LL37,

HBD-2,3 e

LL37,  inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells (IDEC),

inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells (IDEC),

plasmacytoid DC (pDC).

plasmacytoid DC (pDC).

PATTERN RECOGNITION RECEPTORS (PRR)

The arsenal of PRR comprises members of the toll-like receptors (TLR), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein (NOD-like receptors or NLR), retinoic acid-inducible gene, C-type lectin receptors (CLR) and PGLYRPs (peptidoglycan recognition proteins).31,32

TLR family

TLRs are well-known transmembrane proteins that play as innate receptors. In humans, TLR1-10 have been described and they have the ability to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). TLR1, 2, 4-6,10 are in charge of such recognition on the cell surface, whereas TLR3, 7-9 are found in the endosomes.33 They also recognize endogenous ligands in response to tissue damage, contributing to the maintenance of skin barrier.34,35 TLRs are usually expressed both by innate immune cells, such as DC, NK and macrophages, as well as adaptive immune cells, including T and B cells. Activation of TLR triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines, therefore modulating the immune response against pathogens. 33

TLR2 is the receptor that recognizes a broad spectrum of PAMPs, including lipopeptides from Gram-positive bacteria, among others.33 There are reports on genetic variants of TLRs that are associated with AD; however, there is emphasis on TLR2, which is capable of recognizing products of the cell wall of S. aureus. AD individuals are more colonized and infected by S. aureus than non-atopic groups, suggesting that mutations of TLR2 may facilitate such susceptibility.36

NLR family

The NLR (NOD like receptors) family has three distinct subfamilies: the NODs (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein), NLRPs (NOD-like receptor protein) and IPAF (ice protease-activating factor).37

NOD receptors are intracellular receptors that respond to a diversity of microbial products.38 NOD1 (also known as CARD4 - caspase activation and recruitment domain 4), selectively respond to Gram-negative bacteria, and NOD2 recognizes a fragment common to all bacteria. NOD1 changes are associated with elevated IgE levels in AD individuals, and are important indicative factors of atopy susceptibility.39 NOD2 mutations that might result in inappropriate immunomodulation, are not only associated with autoimmune diseases but also with AD.40

NRLPs respond to a large variety of ligands, such as DAMPs (damage-associated molecular patterns), ATP and urate crystals, and exogenous agents, such as asbestos and silica. These receptors form a multiprotein complex, named inflammasome, which leads to the production of IL-1β and IL-18 by activation of caspase 1.37,41 There are four main subclasses of inflammasomes: NRLP3, NLRP1, IPAF (also known as NLRC4-NLR Family, CARD Domain Containing 4) and AIM2 (absent in melanoma 2).37

Changes in expression of NLRP1 gene were associated to AD severity.42 Impaired NLRP3 expression may partially explain how skin colonization and infection with S. aureus can contribute to chronic skin inflammation in AD.43 Increased epidermal expression of IL-1β cytokine has been observed in AD patients presenting FLG mutations.19 It was demonstrated enhanced levels of IL-18 both in sera and culture supernatants under staphylococcal enterotoxin A stimuli in AD patients.44

CLR family

C-Type Lectin Receptors (CLRs) contain C-type lectin-domains, therefore recognizing sugars present in microorganisms. KACL (keratinocyte-associated C-type lectin), expressed by human keratinocytes, is highlighted in this group. It triggers cytolytic activity of Natural killer (NK) cells and cytokine secretion; despite changes in the expression and function of this receptor have not been described in AD, atopic patients exhibit defective cytotoxicity of NK cells.45

Antimicrobial peptides (AMP)

AMPs play an important role in the skin innate immunity acting as endogenous antibiotics. Cathelicidin (LL37) and β-defensin family are the main AMPs, but other keratinocyte products are also recognized for their anti-microbial functions, such as ribonuclease (RNase), S100 family, dermcidin and regenerating islet-derived (REG3α).46

While human β-defensin 1 (HDB1) is expressed by normal human keratinocytes, dermal inflammation induces expression of HBD2, HBD3 and LL37. AD skin lesions have is significantly lower levels of AMPs than psoriatic lesions. Reduced expression and secretion of AMPs may contribute to increased susceptibility to skin infections by viruses, bacteria and fungi in AD patients (Chart 3).32

Chart 3.

Key topics on the innate immune system (part 1)

| Atopic dermatits and innate immune system |

|---|

| • Changes in pathogen recognition receptors |

| • Defects in Toll-like receptor 2 contribute to increased |

| colonization and infection by S. aureus |

| • Anti-mycobians peptides (AMPs) |

| • Main AMPs: catelicidin (LL37) and β-defensin |

| • Decreased AD expression. Favors skin infections |

Dendritic cells (DC)

DC belong to the family of antigen-presenting cells, and are known as sentinels of the immune system, recognizing and presenting antigens, leading to T cell activation.47,48 They lack other markers of leukocyte lineages (CD3, 14, 16, 19, 20, and 56), and express high levels of MHC class II (HLA-DR) molecules.49 A DC lineage-specific marker has not yet been identified, and the subsets of DC in humans and mice are therefore currently defined by lineage − MHC II+ cells, in combination with various cell surface markers.50

There are two major human DC subsets: CD11c+ myeloid DC (mDC) and CD123+ plasmacytoid DC (pDC); mDC are efficient in the uptake, processing, and presentation of foreign antigens, and under Toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation, induce secretion of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12. Conversely, pDC are less effective in these processes and mainly known for their function in antiviral immunity.50 The pDC are a critical source for the antiviral type I IFNs (IFNα and IFNβ), and a reduction of these cells in AD skin, facilitate viral skin infections such as eczema herpeticum.38,51

In AD, a single population of inflammatory DC is well described, which belongs to mDC group. They were initially named inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells (IDEC) based on flow cytometry analysis of cells from epidermal suspensions 52-54. IDEC were defined by the following: HLA-DR+LIN-CD11c+CD1a+ and co-express CD206, CD36, FceRI, IgE, CD1b/c, CD11b, among others.55 Yet, IDECs can be modulated by calcineurin inhibitors and topical corticosteroids.51,56

Natural killer cells (NK)

NK cells are capable of destroying cells infected by microorganisms and tumor cells, without previous activation by reconizing the lack of MHC-I espression on the surface of such cells. They release perforins and protease granzime, promoting target cell lysis, and produce a large variety of cytokines, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, GMCSF, IL-5 and IL-8.51,57 In AD, there is a reduced number of both and in situ and circulating NK.51 In the affected AD tissue, NK cells are in close contact with dendritic cells, indicating that NK cells in direct contact with activated monocytes are ideal targets for apoptosis; this would lead to reduced Th1 cytokine production, and enhanced Th2 immune response, favoring microbial infection.58 Cytokines derived from the keratinocyte, such as TSLP (thymic stromal lymphopoietin), activate NK cells and induce Th2-prone response.59

Regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg)

In patients with AD, circulating regulatory T cells (Treg) (CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ phenotype) are detected in greater numbers and with unchanged immunosuppressive activity.60 These Tregs seem to lose their immunosuppressive activity after stimulation with superantigens, suggesting an increase of effector T cell activation in such individuals.61 Furthermore, the innate immune system produces cytokines inducers of T cells differentiation into Th2, Th17 and Th22.60,61

Other cells of the innate immune system

The innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) group comprises NK cells and ILCs non-NK cells (ILC1, ILC2 and ILC3). They are morphologically very similar to lymphocytes, but lack expression of conventional markers (non-T and non-B cells). They depend on the common γ chain of IL-2 receptor for their development, and on ID2 transcription factor.61 ILC2 has been found in gastrointestinal, skin and lung tissue in humans. Epithelial cytokines IL-25, IL-3 and TSLP, as well as leukotriene D4, activate ILC2 under specific conditions. Studies in animal models of asthma and AD suggest a role of ILC2 in inflammation (Chart 4).62

Chart 4.

Key topics on the innate immune system (part 2)

| Atopic dermatitis and innate immune system (2): |

|---|

| • Dendritic cells (DCs) |

| • Reduced plasmacytoid dendritic cells in skin injured areas by AD, facilitating certain viral skin infections |

| • IDECs can be modulated by calcineurin inhibitors and topical corticosteroids |

| • Natural killer cells (NK) |

| • Reduced NK cells in AD |

| • TSLP (thymic stromal lymphopoietin) activates NK cells and induces Th2 cytokines secretion |

| • Regulatory T cells (Tregs) |

| • Increased circulating Treg |

| • Tregs lose their immunosuppressive activity with superantigens of S. aureus |

| • Non-NK innate lymphoid cells (ILC) |

| • Inflammation-promoting role of ILC-2 in animal |

| models of asthma and AD |

Skin Microbiome

There is a wide group of microorganisms that colonize the skin; rather than passive inhabitants, they actively interact with host cells and influence the innate immune response.63 There is poor bacterial diversity in active lesions of AD, with predominance of S. aureus; once the patient reaches control, the bacterial milieu is then at least partially recovered. Interestingly, the number of commensal bacteria (Staphylococcus epidermidis) increases during exacerbations of AD, suggesting a compensatory mechanism to control S. aureus.64 S. epidermidis produces two AMP (phenol-soluble modulins γ and δ), which are selective for skin pathogens, such as S. aureus, group A Streptococcus, and Escherichia coli, but do not combat S. epidermidis.65 Furthermore, LTA released by S. epidermidis inhibits skin inflammation during tissue damage, through a TLR2-dependent mechanism.66 Finally, small molecules secreted by S. epidermidis increase the expression of human β-defensin by human keratinocytes through TLR2 signaling pathway. These findings evidence a potential inhibition of the skin microflora on survival of cutaneous pathogens, while promoting recovery of the normal skin microbiota.32

The skin microbiota in patients with AD is altered by endogenous factors, such as FLG mutation, or exogenous stimuli, such as soaps, topical corticosteroids and antibiotics, leading to a modified/non-effective response of the host to allergens, pathogens and tissue damage.32

CONCLUSION

Changes in skin barrier seem to play an undoubtful role in the pathogenesis of AD, connecting the structural changes with the innate and adaptive immune system. AD is a prevalent dermatosis, especially among the pediatric population, but may evolve into a refractory disease, non-responsive to standard anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive drugs that are currently available. The search of a better understanding of AD pathogenesis will trigger new specific therapeutical targets.

Footnotes

Study performed atDermatology Department, Faculty of Medicine of Universidade de São Paulo (USP) - São Paulo (SP), Brazil.

Financial Support: FUNADERSP.

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kapoor R, Menon C, Hoffstad O, Bilker W, Leclerc P, Margolis DJ. The prevalence of atopic triad in children with physician-confirmed atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, Robertson CF, Asher MI, Group IPTS Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009. e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elias PM, Hatano Y, Williams ML. Basis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1337–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal R, Woodfolk JA. Skin barrier defects in atopic dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14:433–433. doi: 10.1007/s11882-014-0433-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Addor FA, Aoki V. Skin barrier in atopic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:184–194. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morita K, Miyachi Y, Furuse M. Tight junctions in epidermis: from barrier to keratinization. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:12–17. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown SJ, McLean WH. One remarkable molecule: filaggrin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:751–762. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckhart L, Lippens S, Tschachler E, Declercq W. Cell death by cornification. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:3471–3480. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun R, Celli A, Crumrine D, Hupe M, Adame LC, Pennypacker SD, et al. Lowered humidity produces human epidermal equivalents with enhanced barrier properties. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2015;21:15–22. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2014.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thyssen JP, Kezic S. Causes of epidermal filaggrin reduction and their role in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:792–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong WJ, Richardson T, Seykora JT, Cotsarelis G, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate filaggrin expression and epidermal barrier function. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:454–461. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fluhr JW, Elias PM, Man MQ, Hupe M, Selden C, Sundberg JP, et al. Is the filaggrinhistidine-urocanic acid pathway essential for stratum corneum acidification. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2141–2144. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vavrova K, Henkes D, Struver K, Sochorova M, Skolova B, Witting MY, et al. Filaggrin deficiency leads to impaired lipid profile and altered acidification pathways in a 3D skin construct. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:746–753. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miajlovic H, Fallon PG, Irvine AD, Foster TJ. Effect of filaggrin breakdown products on growth of and protein expression by Staphylococcus aureus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1184–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.09.015. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomura T, Akiyama M, Sandilands A, Nemoto-Hasebe I, Sakai K, Nagasaki A, et al. Specific filaggrin mutations cause ichthyosis vulgaris and are significantly associated with atopic dermatitis in Japan. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1436–1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kezic S, O'Regan GM, Yau N, Sandilands A, Chen H, Campbell LE, et al. Levels of filaggrin degradation products are influenced by both filaggrin genotype and atopic dermatitis severity. Allergy. 2011;66:934–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown SJ, Asai Y, Cordell HJ, Campbell LE, Zhao Y, Liao H, et al. Loss-of-function variants in the filaggrin gene are a significant risk factor for peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell MD, Kim BE, Gao P, Grant AV, Boguniewicz M, Debenedetto A, et al. Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kezic S, O'Regan GM, Lutter R, Jakasa I, Koster ES, Saunders S, et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are associated with enhanced expression of IL-1 cytokines in the stratum corneum of patients with atopic dermatitis and in a murine model of filaggrin deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.989. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf R, Wolf D. Abnormal epidermal barrier in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Clinics in dermatology. 2012;30:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Neill CA, Garrod D. Tight junction proteins and the epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:88–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsukita S, Furuse M. Claudin-based barrier in simple and stratified cellular sheets. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:531–536. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niessen CM. Tight junctions/adherens junctions: basic structure and function. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2525–2532. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hadj-Rabia S, Baala L, Vabres P, Hamel-Teillac D, Jacquemin E, Fabre M, et al. Claudin-1 gene mutations in neonatal sclerosing cholangitis associated with ichthyosis: a tight junction disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1386–1390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Benedetto A, Slifka MK, Rafaels NM, Kuo IH, Georas SN, Boguniewicz M, et al. Reductions in claudin-1 may enhance susceptibility to herpes simplex virus 1 infections in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.014. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turksen K, Troy TC. Barriers built on claudins. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2435–2447. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuki T, Yoshida H, Akazawa Y, Komiya A, Sugiyama Y, Inoue S. Activation of TLR2 enhances tight junction barrier in epidermal keratinocytes. J Immunol. 2011;187:3230–3237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Benedetto A, Rafaels NM, McGirt LY, Ivanov AI, Georas SN, Cheadle C, et al. Tight junction defects in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.018. e1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batista DIS, Perez L, Orfali RL, Zaniboni MC, Samorano LP, Pereira NV, et al. Profile of skin barrier proteins (filaggrin, claudins 1 and 4) and Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokines in adults with atopic dermatitis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2015;29:1091–1095. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokouchi M, Kubo A, Kawasaki H, Yoshida K, Ishii K, Furuse M, et al. Epidermal tight junction barrier function is altered by skin inflammation, but not by filaggrindeficient stratum corneum. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;77:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumagai Y, Akira S. Identification and functions of pattern-recognition receptors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:985–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo IH, Yoshida T, De Benedetto A, Beck LA. The cutaneous innate immune response in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skabytska Y, Kaesler S, Volz T, Biedermann T. The role of innate immune signaling in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and consequences for treatments. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:29–43. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0544-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, Luo Y, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med. 2005;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borkowski AW, Kuo IH, Bernard JJ, Yoshida T, Williams MR, Hung NJ, et al. Tolllike receptor 3 activation is required for normal skin barrier repair following UV damage. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:569–578. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo IH, Carpenter-Mendini A, Yoshida T, McGirt LY, Ivanov AI, Barnes KC, et al. Activation of epidermal toll-like receptor 2 enhances tight junction function: implications for atopic dermatitis and skin barrier repair. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:988–998. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Benedetto A, Agnihothri R, McGirt LY, Bankova LG, Beck LA. Atopic dermatitis: a disease caused by innate immune defects? J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:14–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weidinger S, Klopp N, Rummler L, Wagenpfeil S, Novak N, Baurecht HJ, et al. Association of NOD1 polymorphisms with atopic eczema and related phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weidinger S, Klopp N, Rümmler L, Wagenpfeil S, Baurecht HJ, Gauger A, et al. Association of CARD15 polymorphisms with atopy-related traits in a populationbased cohort of Caucasian adults. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:866–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:707–735. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grigoryev DN, Howell MD, Watkins TN, Chen YC, Cheadle C, Boguniewicz M, et al. Vaccinia virus-specific molecular signature in atopic dermatitis skin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.024. e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niebuhr M, Baumert K, Heratizadeh A, Satzger I, Werfel T. Impaired NLRP3 inflammasome expression and function in atopic dermatitis due to Th2 milieu. Allergy. 2014;69:1058–1067. doi: 10.1111/all.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orfali RL, Sato MN, Takaoka R, Azor MH, Rivitti EA, Hanifin JM, et al. Atopic dermatitis in adults: evaluation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells proliferation response to Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins A and B and analysis of interleukin-18 secretion. Experimental Dermatology. 2009;18:628–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luci C, Gaudy-Marqueste C, Rouzaire P, Audonnet S, Cognet C, Hennino A, et al. Peripheral natural killer cells exhibit qualitative and quantitative changes in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:789–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakatsuji T, Gallo RL. Antimicrobial peptides: old molecules with new ideas. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:887–895. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vittorakis S, Samitas K, Tousa S, Zervas E, Aggelakopoulou M, Semitekolou M, et al. Circulating conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cell subsets display distinct kinetics during in vivo repeated allergen skin challenges in atopic subjects. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:231036–231036. doi: 10.1155/2014/231036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida K, Kubo A, Fujita H, Yokouchi M, Ishii K, Kawasaki H, et al. Distinct behavior of human Langerhans cells and inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells at tight junctions in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi Y, Ishii Y, Hata-Suzuki M, Arai R, Chibana K, Takemasa A, et al. Comparative analysis of circulating dendritic cell subsets in patients with atopic diseases and sarcoidosis. Respir Res. 2013;14:29–29. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sato K, Fujita S. Dendritic cells: nature and classification. Allergol Int. 2007;56:183–191. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.R-06-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wollenberg A, Räwer HC, Schauber J. Innate immunity in atopic dermatitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011;41:272–281. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bieber T. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of human antigen-presenting cells expressing the high affinity receptor for IgE (Fc epsilon RI) Immunobiology. 2007;212:499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wollenberg A, Kraft S, Hanau D, Bieber T. Immunomorphological and ultrastructural characterization of Langerhans cells and a novel, inflammatory dendritic epidermal cell (IDEC) population in lesional skin of atopic eczema. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:446–453. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12343596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaba LC, Krueger JG, Lowes MA. Resident and "inflammatory" dendritic cells in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:302–308. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guttman-Yassky E, Lowes MA, Fuentes-Duculan J, Whynot J, Novitskaya I, Cardinale I, et al. Major differences in inflammatory dendritic cells and their products distinguish atopic dermatitis from psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1210–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schuller E, Oppel T, Bornhövd E, Wetzel S, Wollenberg A. Tacrolimus ointment causes inflammatory dendritic epidermal cell depletion but no Langerhans cell apoptosis in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deniz G, van de Veen W, Akdis M. Natural killer cells in patients with allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cork MJ, Danby SG, Vasilopoulos Y, Hadgraft J, Lane ME, Moustafa M, et al. Epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1892–1908. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu WH, Park CO, Oh SH, Kim HJ, Kwon YS, Bae BG, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-activated invariant natural killer T cells trigger an innate allergic immune response in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:290–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.024. 9 e1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Atopic dermatitis: a disease of altered skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:233–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spits H, Cupedo T. Innate lymphoid cells: emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:647–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mjosberg J, Eidsmo L. Update on innate lymphoid cells in atopic and non-atopic inflammation in the airways and skin. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:1033–1043. doi: 10.1111/cea.12353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cogen AL, Nizet V, Gallo RL. Skin microbiota: a source of disease or defence? Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:442–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, Conlan S, Grice EA, Beatson MA, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in childrenwith atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850–859. doi: 10.1101/gr.131029.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cogen AL, Yamasaki K, Sanchez KM, Dorschner RA, Lai Y, MacLeod DT, et al. Selective antimicrobial action is provided by phenol-soluble modulins derived from Staphylococcus epidermidis, a normal resident of the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:192–200. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lai Y, Di Nardo A, Nakatsuji T, Leichtle A, Yang Y, Cogen AL, et al. Commensal bacteria regulate Toll-like receptor 3-dependent inflammation after skin injury. Nat Med. 2009;15:1377–1382. doi: 10.1038/nm.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]