Abstract

Background

Timing and trajectories of cardiovascular risk factor (CVRF) development in relation to atrial fibrillation (AF) have not been previously described. We assessed trajectories of CVRF and incidence of AF over 25 years in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

Methods

We assessed trajectories of CVRF in 2456 individuals with incident AF and 6414 matched controls. Subsequently, we determined the association of CVRF trajectories with the incidence of AF among 10,559 AF-free individuals (mean age 67, 52% men, 20% blacks). Risk factors were measured during 5 exams between 1987-2013. Cardiovascular events, including incident AF, were continuously ascertained. We modeled the prevalence of risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes in the period before and after AF diagnosis and the corresponding index date for controls using generalized estimating equations. Trajectories in risk factors were identified using latent mixture modeling. The risk of incident AF by trajectory group was examined using Cox models.

Results

The prevalence of stroke, myocardial infarction, and heart failure increased steeply during the time close to AF diagnosis. All CVRFs were elevated in AF cases compared to controls >15 years prior to diagnosis. We identified distinct trajectories for all the assessed CVRFs. In general, individuals with trajectories denoting long-term exposure to CVRFs had increased AF risk even after adjustment for single measurements of the CVRFs.

Conclusion

AF patients have increased prevalence of CVRF many years before disease diagnosis. This analysis identified diverse trajectories in the prevalence of these risk factors, highlighting their different roles in AF pathogenesis.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, cardiovascular diseases, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, with a lifetime risk of 1 in 4 in the general population and an increasing prevalence as the population ages.1 Major risk factors for AF include age, white race, obesity, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and a history of myocardial infarction (MI) and heart failure (HF).2-6 These risk factors are similar to the risk factors for cardiovascular disease in general, and these cardiovascular outcomes often precede an AF event.7 The development of AF is also associated with subsequent increased risk of cardiovascular death,8, 9 HF,10 MI,11, 12 and stroke.13

Despite the extensive literature on risk factors for AF, little attention has been devoted to the timing of risk factor development in relation to AF diagnosis; exceptions are stroke as an outcome of AF, and HF as both a risk factor for and outcome of AF. While it is known that AF is a risk factor for stroke and, therefore, most often precedes it,14 AF and HF show a bidirectional relation, and the existing severity of specific cardiovascular risk factors, along with age and sex, may determine whether AF or HF occurs first.15, 16 However, no information exists on the timing, relative to AF diagnosis, of the development of other AF risk factors such as hypertension or obesity. This information can be useful to better understand the factors that influence the progress of the cardiac substrate facilitating the onset of AF and, therefore, develop preventive strategies.

Furthermore, healthcare utilization, particularly cardiovascular-related utilization, is higher among patients with AF than among non-AF individuals even after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors.17 Exploring how trajectories in cardiovascular risk factor prevalence differ between individuals with and without AF could help to understand observed differences in healthcare utilization. Risk factor trajectories could also be clinically relevant and informative in the prevention of AF, and may provide more information than a one-time measurement. With the overall goal of assessing the association of trajectories of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes with AF, we addressed the following 2 aims: 1) To describe the long term prevalence of risk factors preceding AF diagnosis and the subsequent development of cardiovascular outcomes after diagnosis, and compare the risk factors and outcomes by AF status; 2) To identify subgroups of individuals with similar trajectories of risk factors and outcomes, and determine the association of these trajectory subgroups with the subsequent development of AF. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a population-based study with a 25-year follow-up and a large number of incident AF cases, provides an exceptional opportunity to describe these trajectories and assess their impact on AF risk.

METHODS

Study population

The ARIC study is a mostly biracial, prospective cohort study of cardiovascular disease and atherosclerosis risk factors.18 Participants at baseline (1987-1989) included 15,792 men and women aged 45-64, recruited from 4 communities in the US (Washington County, Maryland; the northwest suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota; Jackson, Mississippi; and Forsyth County, North Carolina). ARIC participants were mostly white in the Washington County and Minneapolis centers, only African-American in the Jackson center, and included both races in Forsyth County. After the initial assessment, study participants were examined 4 additional times (1990-92 (visit 2), 1993-95 (visit 3), 1996-98 (visit 4), 2011-13 (visit 5)). Additionally, ARIC participants receive annual follow-up calls, with response rates of ≥ 90% among survivors.

Of the 15,792 participants who attended visit 1 in the ARIC study, we excluded individuals who were of a racial group other than white or African-American and nonwhites in the Minneapolis and Washington County field centers (n=103), those with prevalent AF at visit 1 (n=37), and those with low quality or missing ECG (n=242). After exclusions, our study population included 15,410 participants (26% African-American, 45% male). For aim 1, our analysis included 2456 individuals with AF diagnosed during the follow-up and 6414 matched controls without AF. For aim 2, we included 10,559 individuals with measured risk factors at the first 4 visits, and without prevalent AF at visit 4.

This study was approved by institutional review boards at each participating center and all study participants provided written informed consent.

AF ascertainment

AF diagnoses were ascertained by 3 different sources in the ARIC study: electrocardiograms (ECG) performed at study visits, hospital discharge codes, and death certificates.3 At each ARIC study visit, a 10-second 12-lead ECG was performed using a MAC PC cardiograph (Marquette Electronics Inc, Milwaukee, WI) and transmitted to the ARIC ECG Reading Center for coding, interpretation and storage. All ECGs automatically coded as AF were visually checked by a trained cardiologist to confirm AF diagnosis.19 Annual follow-up calls and review of local hospital discharges identified hospitalizations in ARIC participants through the end of 2012. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes of 427.31 (atrial fibrillation) or 427.32 (atrial flutter) listed as a discharge diagnostic code in any position defined AF cases. AF events associated with cardiac surgery were not included in this study. Validity of ICD codes for AF is adequate as approximately 90% of the cases were confirmed in a physician review of discharge summaries from 125 possible AF cases.3 AF cases were also identified if code ICD-9 427.3 or International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code I48 was listed as a cause of death. In this analysis, the AF incident date was defined as the date of the first ECG showing AF (4% of our AF cases), the first hospital discharge with AF coded (96% of AF cases), or when AF was listed as a cause of death (0.1% of cases), whichever occurred earlier.

Risk factor and outcome ascertainment

At baseline and during follow-up exams, participants reported information on smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, use of medications, and underwent a physical exam. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Blood pressure was measured using a random-zero sphygmomanometer after 5 minutes of rest in the sitting position, and was defined as the average of the 2nd and 3rd measurements taken. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg or use of anti-hypertensive medications. In analysis using continuous SBP, a constant of 10 mmHg was added to the participant’s measure if they were taking anti-hypertension medications.20 Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L), non-fasting glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), treatment for diabetes mellitus, or self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes. Prevalent HF was defined as the reported use of HF medication in the previous two weeks, presence of HF according the Gothenburg criteria (only at the baseline visit), or having had a HF hospitalization since the previous visit.21 Incident HF was defined as the first occurrence of any listing of an ICD-9-CM code 428 for a hospitalization during follow-up.22 Prevalent MI at baseline was defined as a self-reported physician-diagnosed MI or presence of a MI by ECG, and incident MI was ascertained by study visit ECGs or the ARIC Morbidity and Mortality Classification Committee, by using data from follow-up calls, hospitalization records and death certificates.23 Prevalent stroke at baseline was defined as the self-reported physician diagnosis of a stroke prior to visit 1, and incident stroke was defined as the sudden or rapid onset of neurological symptoms lasting for at least 24 hours or leading to death in the absence of evidence for a non-stroke cause, and was validated using established criteria with physician review of records.24

Covariates measured at baseline (visit 1) included sex, race, and study center. Information on smoking, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, HF, MI, stroke, and AF was obtained during each of the 5 study exams between 1987 and 2013. AF, HF, MI and stroke also were ascertained from annual surveillance.

Statistical analysis

For Aim 1, to assess the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes in persons with AF vs. AF-free controls, we compared risk factors and outcomes both before and after AF diagnosis to those in individuals without AF. Each AF case was matched with up to 3 controls by age (± 2 years), sex, race, and field center. We defined index date (time t=0) as the date of AF diagnosis for each case and the same date for the corresponding matched controls. Time to each visit was re-calculated in relation to the index date as time at visit i (ti) = visit i date − index date (in years). Negative and positive values correspond to exams before and after the study index date, respectively.

Using a dataset with one observation per person-visit (maximum 5 observations per participant), we fit generalized estimating equation (GEE) models with a logistic link with time in years before/after index date as the main independent variable. Time was categorized in 5-year periods (<−17.5, −17.5 to <−12.5, −12.5 to <−7.5, -7.5 to <−2.5, −2.5 to +2.5 (reference), and >+2.5 years). We chose a reference time of ± 2.5 years to account for imprecise AF diagnosis, and chose 5 year increments for easy descriptive purposes. Separate models were used to predict the prevalence of risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes (hypertension, smoking, obesity, diabetes, HF, MI, and stroke) in each time period separately for AF cases and controls and by race. To describe the changes in risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes over time in those with and without AF, adjusted odds ratios (OR) were calculated using the same GEE models, and also using the index date ±2.5 years as the reference group. The interaction of time with AF status was used to test for differences in the OR trajectories in cases and controls.

For Aim 2, we included 10,559 individuals with measurements at the first 4 visits (during years 1987-1998) and without AF at the time of visit 4, and identified risk factor trajectories during those years. Then we determined the association of each trajectory with the risk of incident AF through the end of 2013. We used latent class models to identify distinct subgroups within the ARIC cohort sharing a similar underlying trajectory for each risk factor. These models were fit using SAS Proc Traj.25-27 The supplemental materials include additional details on the trajectory modeling process. The association of each trajectory group with the risk of incident AF was modeled using Cox proportional hazards models comparing the risk in each trajectory group with the reference trajectory group. Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, and each of the other risk factors (BMI, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and a history of MI, HF or stroke) measured at visit 4. An additional model adjusted for the measure of the continuous variable risk factor at visit 4 to determine if the previous trajectory itself provided more predictive information on the association with AF than a one-time measurement. This additional adjustment was possible for BMI, SBP, and current smoking, but not for diabetes, HF, MI, or stroke due to model fit issues derived from complete separation of the data. Follow-up time for Cox models began at visit 4, and continued until the date of AF, the end of follow-up (2013), death, or the date of last contact. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS v 9.3 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

For Aim 1, during a median follow-up of 24 years (interquartile range = 20.5-25.0 years), 2456 cases of AF were detected (19% black race; 54% male), and matched with 6414 controls without AF. Characteristics of AF cases and controls at the index date are included in table 1. Compared to controls, AF cases had higher BMI and greater prevalence of current smoking, hypertension, diabetes, HF, MI and stroke. The mean number of visits attended by AF cases and matched controls was 3.8 and 4.1, respectively. The mean calendar year of AF diagnosis was 2003.

Table 1.

Prevalent characteristics in AF cases at the time of AF diagnosis, and in matched controls at the corresponding index date, ARIC, 1987-2013.

| AF Cases (n=2456) |

Controls (n=6414) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Calendar year of diagnosis / Index date | 2003 (6.6) | 2003 (6.6) |

| Matched variables | ||

| Age, years | 66.7 (8.7) | 67.4 (8.4) |

| Black race, % | 18.9 | 20.5 |

| Male sex, % | 53.6 | 51.2 |

| Other variables | ||

| Obese, (BMI > 30) % | 35.1 | 28.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.9 (5.9) | 28.0 (5.1) |

| Current smoker, % | 17.3 | 14.3 |

| Hypertension, % | 69.8 | 57.4 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 130.0 (21.9) | 128.5 (19.7) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 70.5 (12.5) | 69.6 (10.8) |

| Diabetes, % | 32.3 | 22.4 |

| Heart Failure, % | 25.3 | 5.0 |

| Myocardial infarction, % | 19.7 | 8.3 |

| Stroke, % | 8.2 | 3.4 |

*Values correspond to mean (SD) unless otherwise noted

† AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index

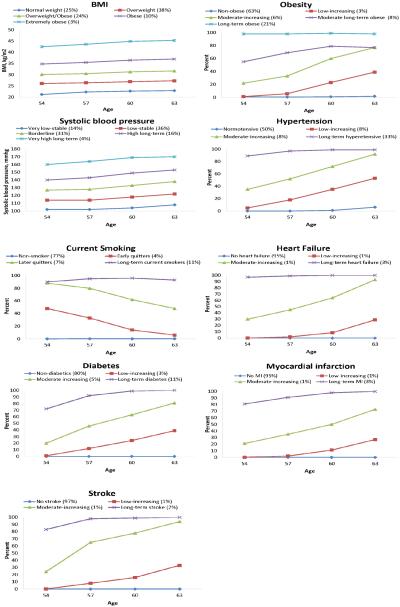

The age and sex-adjusted prevalence of risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes by AF status and race is depicted in Figure 1. Cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes were more prevalent in AF cases than in matched controls. This increased prevalence was present for all risk factors and outcomes from the beginning of follow-up, and was significantly higher for obesity, smoking and HF even in the period <−17.5 years before index date (p<0.05). Blacks with AF had the highest prevalence for each risk factor and cardiovascular outcome both before and after developing AF, while the prevalences were lowest in white controls. For both race groups, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes increased gradually over time, up to and after the index date. The prevalence of smoking and obesity increased slightly during follow-up but started to decline around the index date. The prevalence of HF, stroke and MI in AF cases had a J-shape pattern, with low prevalence in the 10+ years before AF, and steep increases in prevalence during the period of time close to AF diagnosis. The prevalence of HF, stroke and MI in controls remained low throughout follow-up for both blacks and whites.

Figure 1.

Predicted prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes over time by AF status, ARIC, 1987-2011. Adjusted prevalence was modeled using general estimating equations held constant for age, race and sex. Predicted probabilities of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes were then calculated based on a 65 year old male, stratified by race.

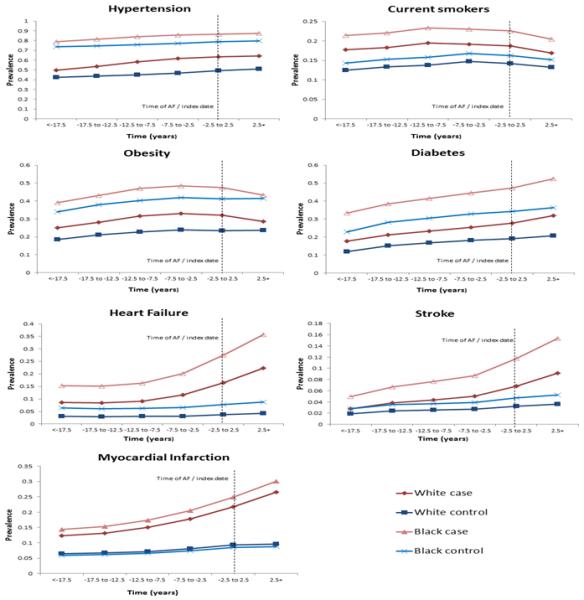

Figure 2 depicts the change in the prevalence of risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes in AF cases, adjusted for age, race and sex. We observed diverse odds ratio trajectories in the prevalence of risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes among AF patients, with steep increases in the prevalence of stroke, MI and HF during the time period closest to AF diagnosis. Odds ratio trajectories for hypertension and diabetes showed monotonic increases over time, and those for smoking and obesity suggested decreases after AF diagnosis. An odds ratio <1 or >1 can be interpreted as a lower or higher odds, respectively, of the corresponding risk factor or outcome at a particular time period compared with the odds at the time of AF diagnosis date. The odds of having HF around 10 years prior to AF diagnosis is approximately 50% lower when compared to having HF at the time of AF, whereas the odds of having diabetes or hypertension is only about 20% lower 10 years prior to AF. The odds ratios over time for hypertension, obesity, HF, stroke and MI were significantly different based on AF status (p<0.05 for all the interaction terms), with lower increments among those without AF.

Figure 2.

Odds ratios (OR) of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes over time, based on AF status, adjusted for age, race and sex. OR <1 or >1 can be interpreted as a lower or higher odds, respectively, of the risk factor or cardiovascular outcome at a particular time period compared with the odds at the time of AF diagnosis date.

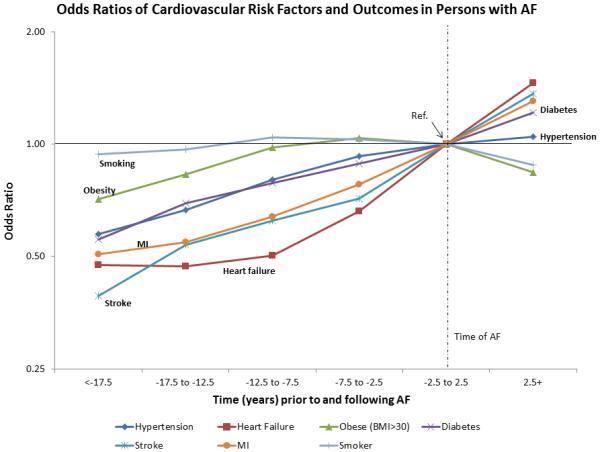

For aim 2, trajectories for each of the cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes were fit to the 10,559 participants who participated in the first 4 visits and were free of AF at visit 4. These trajectories are depicted in Figure 3. Five distinct trajectories were identified for BMI, obesity, and SBP, and 4 distinct trajectories were identified for hypertension, smoking, diabetes, HF, MI and stroke. The trajectory analysis for BMI and SBP identified subsets with different baseline values but parallel increases in the values of the risk factor over the 9-year period. In contrast, for obesity, hypertension, diabetes, HF, MI and stroke, we identified a group without the condition during the 9-year period, a group with prevalence close to 100% during the follow-up, and 2 or 3 intermediate groups in which the prevalence increased at different rates during the 9-year period. For smoking, the trajectory analysis identified a group of non-smokers (77% of the cohort), a group of long-term current smokers (11% of the cohort), and 2 smaller groups that quit smoking at similar rates.

Figure 3.

Trajectories in risk factors and outcomes over time, ARIC, 1987-1998. Groups are trajectory groups (percentage of the population in each group).

During follow-up of these trajectory groups (median follow-up = 15 years), 1507 cases of incident AF were detected. The association of each trajectory group for each risk factor and outcome is presented in table 2. For each risk factor, the trajectory group with the most favorable profile (group 1) was the reference to which the other trajectory groups were compared. For all risk factors, risk of incident AF was highest among individuals in the trajectory group with the highest prevalence of risk factor values and lowest in the reference trajectory group. The long-term obese (obesity trajectory group 5), had a 39% (95% confidence interval [CI], 14-70%) increased risk of AF compared to the reference trajectory group (non-obese), even after adjusting for BMI measured at visit 4. Similarly, the SBP trajectory groups with high and very high long-term SBP, who had average SBP >140 for >9 years, had an increased risk of AF, even after adjustment for SBP measured at visit 4. These results were consistent with the hypertension analysis, in which hypertension trajectory group 4 (long-term hypertensives) had a HR (95% CI) of 1.31 (1.14-1.51) compared to the reference group, even after adjustment for visit 4 SBP. Compared with long-term non-smokers (smoking trajectory group 1), the long-term current smokers (trajectory group 4) had increased risk of AF, even after adjusting for smoking status at visit 4. The risk of AF among those who quit (trajectory groups 2 and 3) was intermediate. The risk of AF was higher in the trajectories containing participants with long-term (trajectory group 4) or newly diagnosed (trajectory groups 2 and 3) diabetes, HF, MI and stroke compared to those without the disease (trajectory group 1).

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) of atrial fibrillation by risk factor trajectory groups, ARIC, 1998-2013.

| Trajectory groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| BMI | Normal weight | Overweight | Overweight/obese | Obese | Extremely obese |

| N, % | 2607 (25%) | 4025 (38%) | 2548 (24%) | 1086 (10%) | 293 (3%) |

| # AF | 325 | 535 | 401 | 187 | 59 |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 0.98 (0.85-1.12) | 1.33 (1.14-1.55) | 1.66 (1.37-2.01) | 2.56 (1.91-3.43) |

| Model 1 + V4 BMI | 1 (REF) | 0.90 (0.75-1.07) | 1.13 (0.87-1.47) | 1.28 (0.86-1.90) | 1.70 (0.92-3.14) |

| Obesity (≥30) | Non-obese | Low-increasing | Moderate-increasing | Moderate long- term obese |

Long-term obese |

| N, % | 6615 (63%) | 292 (3%) | 605 (6%) | 802 (8%) | 2245 (21%) |

| # AF | 837 | 57 | 87 | 100 | 426 |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.03 (0.78-1.35) | 1.35 (1.08-1.69) | 1.18 (0.96-1.45) | 1.68 (1.48-1.91) |

| Model 1 + V4 BMI | 1 (REF) | 0.93 (0.70-1.23) | 1.21 (0.95-1.54) | 1.07 (0.86-1.34) | 1.39 (1.14-1.70) |

| SBP | Very low-stable | Low-stable | Borderline | High long-term | Very high long-term |

| N, % | 1464 (14%) | 3773 (36%) | 3228 (31%) | 1713 (16%) | 381 (4%) |

| # AF | 170 | 450 | 490 | 312 | 85 |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.02 (0.86-1.22) | 1.32 (1.11-1.59) | 1.73 (1.42-2.10) | 2.52 (1.92-3.30) |

| Model 1 + V4 SBP | 1 (REF) | 0.96 (0.79-1.16) | 1.16 (0.93-1.46) | 1.43 (1.08-1.89) | 1.94 (1.32-2.86) |

| Hypertension | Normotensive | Low-increasing | Moderate-increasing | Long-term hypertensive | |

| N, % | 5321 (50%) | 878 (8%) | 866 (8%) | 3494 (33%) | |

| # AF | 583 | 178 | 99 | 647 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.43 (1.21-1.70) | 1.30 (1.04-1.61) | 1.57 (1.39-1.77) | |

| Model 1 + V4 SBP | 1 (REF) | 1.23 (1.02-1.47) | 1.10 (0.88-1.39) | 1.31 (1.14-1.51) | |

| Current smoking | Non-smoker | Early quitters | Later quitters | Long-term current smokers | |

| N, % | 8175 (77%) | 439 (4%) | 743 (7%) | 1202 (11%) | |

| # AF | 1116 | 50 | 132 | 209 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.22 (0.92-1.63) | 1.57 (1.31-1.88) | 1.78 (1.53-2.07) | |

| Model 1 + V4 current smoking |

1 (REF) | 1.23 (0.92-1.64) | 1.48 (1.21-1.81) | 1.43 (1.03-2.00) | |

| Diabetes | Non-diabetics | Low-increasing | Moderate-increasing | Long-term diabetes | |

| N, % | 8497 (80%) | 328 (3%) | 529 (5%) | 1205 (11%) | |

| # AF | 1096 | 85 | 91 | 235 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.29 (1.03-1.62) | 1.28 (1.03-1.59) | 1.57 (1.36-1.82) | |

| Heart failure | No heart failure | Low-increasing | Moderate-increasing | Long-term heart failure | |

| N, % | 10,066 (95%) | 77 (1%) | 60 (1%) | 356 (3%) | |

| # AF | 1368 | 29 | 22 | 88 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.91 (1.31-2.78) | 3.06 (1.99-4.70) | 1.59 (1.27-1.98) | |

| MI | No MI | Low-increasing | Moderate-increasing | Long-term MI | |

| N, % | 10,035 (95%) | 84 (1%) | 120 (1%) | 320 (3%) | |

| # AF | 1360 | 29 | 34 | 84 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.82 (1.25-2.64) | 2.02 (1.43-2.85) | 1.77 (1.41-2.21) | |

| Stroke | No stroke | Low-increasing | Moderate-increasing | Long-term stroke | |

| N, % | 10,229 (97%) | 74 (1%) | 76 (1%) | 180 (2%) | |

| # AF | 1434 | 19 | 17 | 37 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.37 (0.87-2.16) | 1.57 (0.96-2.54) | 1.68 (1.21-2.33) | |

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, BMI, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, history of MI, history of heart failure, history of stroke where appropriate

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; AF, atrial fibrillation; V4, visit 4; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction

DISCUSSION

In this large population-based study describing the timing of risk factors and outcomes in relation to AF diagnosis, we observed diverse trajectories in the prevalence of risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes. We also found that trajectories of risk factors are associated with the future risk of AF, providing additional information beyond that obtained from single risk factor measurements. In the first aim, there were steep increases in the prevalence of stroke, MI and HF during the years proximal to the AF diagnosis, while prevalences for hypertension and diabetes showed monotonic increases over time, and those for smoking and obesity suggested decreases in prevalence after AF diagnosis. The odds ratios over time for hypertension, obesity, HF, stroke and MI were significantly different based on AF status, with lower increments among those without AF. Also, we found that the prevalence of most cardiovascular risk factors was higher in individuals with AF compared to AF-free controls even 15 years or more before the diagnosis of AF. In Aim 2, we observed that those with prevalent risk factors, and those that have had them for a longer duration, had an increased risk of AF. Participants with high blood pressure or who have been obese for a longer period of time have an even higher risk, and the time since onset may be important. These results underscore the role of factors such as hypertension and obesity in contributing to the development of the atrial substrate that eventually leads to the clinical onset of AF, and the need to act earlier in the pathogenic process to be able to prevent this common arrhythmia.

Few studies have considered the timing of risk factor development in relation to AF diagnosis. Most current information consists of the well-known association of increased stroke risk following an AF event,14 and for this reason, the 2014 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients with AF recommend oral anticoagulation in patients with a moderate or greater risk of ischemic stroke.28 The studies that address the timing of AF and HF development show a bidirectional association, and the existing severity of specific cardiovascular risk factors such as BMI, diabetes and previous MI, along with age and sex, may determine whether AF or HF occurs first in the individual. 15, 16 Which event develops first also may be indicative of the overall health of the patient, as it has been shown that among hospitalized patients with both AF and HF, AF more frequently developed first.29 HF onset in patients with previous AF has been associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality.16, 30

Though less documented, it appears MI and AF also can occur concurrently. In a meta-analysis, AF onset in MI patients is associated with higher mortality, (odds ratio (95% confidence interval) = 1.46 (1.35-1.58)), and this worse prognosis persisted regardless of the timing of AF, suggesting that AF is a major adverse health event for those with MI.31, 32 Several other studies have shown that AF is associated with an increased risk of MI,11, 33 particularly non-ST elevation MI, and that this association was stronger in women.12

While stroke, MI and HF are all relatively discrete cardiovascular events, with the highest prevalence following AF diagnosis, the trajectories in prevalence of traditional risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes are much different, showing monotonic increases over time. Both hypertension and diabetes are associated with increased risk of AF, independent of other risk factors, and the trajectories depicted in this analysis corroborate that the long-term effects of each chronic condition could take many years, even decades, to appear. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the role of hypertension as a risk factor for AF over time. Chronic increased systemic blood pressure leads to left ventricular hypertrophy, impaired ventricular filling, left atrial enlargement, and slowing of atrial conduction velocity.34 High blood pressure causes structural and functional changes in the myocardium, leading to an increased risk of arrhythmia.35 Similarly, the damaging impact of diabetes on AF risk occurs after prolonged exposure to diabetes, and several mechanisms have been proposed. Diabetes could place metabolic stress on the atrium or through association with systemic illnesses such as infection or renal failure.36 Also, high HbA1c levels and the severity of diabetes and long-term cumulative exposure to hyperglycemia could induce AF.37 Several other theories involve atrial dilation, elevated inflammation factors such as C-reactive protein, and electrical remodeling of atria.38

Obesity is associated with higher risk of AF, possibly through increased risk of diabetes and hypertension, and through the association of high body mass with the metabolic syndrome, chronic inflammation, and stress. Obesity also increases atrial size and is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy.34, 35 Smoking also is associated with AF in both current and former smokers and the association is higher in those with more pack years.7, 39 Nicotine increases heart rate and blood pressure, and smoking causes decreased lung function and leads to chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, which are also risk factors for AF. 4, 39 In this analysis, we see a higher prevalence of smoking and obesity in AF cases throughout the entire follow-up, increasing slightly over time up to AF diagnosis and then decreasing around the time of AF and afterwards. This decrease could be due to either health issues causing weight loss, or a diagnosis of AF instigating lifestyle changes leading to weight loss and smoking cessation.

As previously shown in the ARIC study, AF is more common in whites than in blacks, despite the higher prevalence of co-morbidities and cardiovascular outcomes in blacks.3 This new analysis reports a higher prevalence of all risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes in blacks with AF or without AF compared to their white counterparts throughout the entire follow-up, with the highest prevalence in blacks with AF.

This study describing the prevalence and trajectories of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes in AF cases has relevant clinical and public health implications. First, it reinforces the concurrent nature of cardiovascular events such as HF, MI and stroke as major adverse events that tend to cluster around the time of AF. For newly diagnosed AF cases, treatment should involve the prevention and early detection of these other cardiovascular events. For patients with previous MI or HF, prevention and early detection of AF could lead to better outcomes. Second, this study implies that chronic conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, smoking and obesity cause damage to the cardiovascular system over an extended amount of time. Targeting these upstream risk factors could prevent AF in addition to other cardiovascular diseases; treatment for these conditions should emphasize long-term control to minimize the risks of eventual cardiovascular events, such as AF. The decreased risk of AF in former smokers compared to current smokers could have clinical implications, and future studies should explore the effects of improvement in risk factors, including smoking cessation, on the risk of AF. Third, the timing of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes, relative to AF diagnosis, is useful to better understand the pathogenesis of AF, and should be used to further causation theories and to develop preventive strategies. Fourth, the distinct trajectory groups could contribute to identify subsets of AF patients with shared etiology and pathophysiologic mechanisms, which may result in more targeted treatments and preventive strategies. Lastly, these trajectories could be used to help explain observed differences in healthcare utilization in those with and without AF, and can be used to develop plans for healthcare resource allocation.

Limitations of this study include possible misclassification of the HF and AF diagnoses, which were based mostly on ICD discharge codes. Similarly, outpatient AF cases were not captured, so it is possible that some paroxysmal/intermittent AF cases were undetected. Bias may also occur if AF was detected as an incidental finding during a hospitalization for some other reason, such as a cardiovascular event. However, it has been shown that AF diagnosed by ICD codes and from study visit ECGs has a positive predictive value of ~90%,3 and validity of HF in ARIC is ~90%.40 For aim 1, we used AF diagnosis date ± 2.5 years to capture the time period around the diagnosis, since participants could have episodes of AF occurring before they were diagnosed. Selection bias is a concern, particularly after the index date, as those who live longer may have an overall healthier cardiovascular profile compared to someone who died shortly after AF.

Despite these limitations, our study has numerous key strengths. This is a large community-based cohort, with a biracial sample, repeat study visits with comparable assessment of risk factors over time, and long-term annual follow-up, giving us the ability to observe health trends over 25 years. There are a large number of cardiovascular and AF events with good quality data on risk factors and detailed ascertainment and adjudication of cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes.

CONCLUSION

In this large population-based study, we report increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in AF patients more than 15 years before their diagnosis. The prevalence of cardiovascular outcomes increased after AF diagnosis, and trajectories differed by AF status. We also found diverse trajectories in the prevalence of risk factors and cardiovascular outcomes, suggesting they could have different roles in the pathogenesis of AF.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

Using follow-up from a large community-based cohort, we assessed the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and atrial fibrillation (AF)-related outcomes over time by AF status, and explored the association of trajectories of risk factors with incident AF. Stroke, myocardial infarction and heart failure prevalence increased steeply around the time of AF, while monotonic increases in hypertension and diabetes prevalence over many years were associated with AF risk.

A trajectory analysis showed that not only presence of risk factors such as hypertension and obesity, but also their duration was more informative in determining AF risk compared to 1-time clinical measurements.

What are the clinical implications?

Exploring the timing and trajectories of risk factor development in relation to AF diagnosis could provide insights into the pathogenesis of this common arrhythmia and inform prevention strategies.

This large, community-based study with 25 years of follow-up demonstrated an increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in AF patients many years before disease diagnosis and identified diverse trajectories in the prevalence of these risk factors, highlighting their different roles in AF pathogenesis, and the need to establish preventive strategies that address risk factors decades before AF diagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

FUNDING SOURCES

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN26820110 0012C). This work was additionally supported by American Heart Association grant 16EIA26410001 (Alonso).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, D'Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 2004;110:1042–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140263.20897.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso A, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Stepas KA, Pencina MJ, Moser CB, Sinner MF, Sotoodehnia N, Fontes JD, Janssens AC, Kronmal RA, Magnani JW, Witteman JC, Chamberlain AM, Lubitz SA, Schnabel RB, Agarwal SK, McManus DD, Ellinor PT, Larson MG, Burke GL, Launer LJ, Hofman A, Levy D, Gottdiener JS, Kaab S, Couper D, Harris TB, Soliman EZ, Stricker BH, Gudnason V, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ. Simple risk model predicts incidence of atrial fibrillation in a racially and geographically diverse population: The charge-af consortium. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2:e000102. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso A, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Ambrose M, Chamberlain AM, Prineas RJ, Folsom AR. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in whites and african-americans: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. American heart journal. 2009;158:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Kuller LH, Kronmal RA, Cushman M, Fried LP, White R, Furberg CD, Rautaharju PM. Incidence of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation in older adults. Circulation. 1997;96:2455–2461. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanoski CA. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and impact of atrial fibrillation. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2010;67:S11–16. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang TJ, Parise H, Levy D, D'Agostino RB, Sr., Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:2471–2477. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.20.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The framingham heart study. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Cha SS, Gersh BJ, Seward JB, Tsang TS. Mortality trends in patients diagnosed with first atrial fibrillation: A 21-year community-based study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49:986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, McMurray JJ. A population-based study of the long-term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the renfrew/paisley study. The American journal of medicine. 2002;113:359–364. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soliman EZ, Safford MM, Muntner P, Khodneva Y, Dawood FZ, Zakai NA, Thacker EL, Judd S, Howard VJ, Howard G, Herrington DM, Cushman M. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174:107–114. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soliman EZ, Lopez F, O'Neal WT, Chen LY, Bengtson L, Zhang ZM, Loehr L, Cushman M, Alonso A. Atrial fibrillation and risk of st-segment-elevation versus non-st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. Circulation. 2015;131:1843–1850. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The framingham study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1991;22:983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardiogenic brain embolism Cerebral embolism task force. Archives of neurology. 1986;43:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnabel RB, Rienstra M, Sullivan LM, Sun JX, Moser CB, Levy D, Pencina MJ, Fontes JD, Magnani JW, McManus DD, Lubitz SA, Tadros TM, Wang TJ, Ellinor PT, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ. Risk assessment for incident heart failure in individuals with atrial fibrillation. European journal of heart failure. 2013;15:843–849. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, Leip EP, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Murabito JM, Kannel WB, Benjamin EJ. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 2003;107:2920–2925. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bengtson LG, Lutsey PL, Loehr LR, Kucharska-Newton A, Chen LY, Chamberlain AM, Wruck LM, Duval S, Stearns SC, Alonso A. Impact of atrial fibrillation on healthcare utilization in the community: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2014;3:e001006. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study: Design and objectives. The aric investigators. American journal of epidemiology. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Case LD, Zhang ZM, Goff DC., Jr Ethnic distribution of ecg predictors of atrial fibrillation and its impact on understanding the ethnic distribution of ischemic stroke in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40:1204–1211. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobin MD, Sheehan NA, Scurrah KJ, Burton PR. Adjusting for treatment effects in studies of quantitative traits: Antihypertensive therapy and systolic blood pressure. Statistics in medicine. 2005;24:2911–2935. doi: 10.1002/sim.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eriksson H, Caidahl K, Larsson B, Ohlson LO, Welin L, Wilhelmsen L, Svardsudd K. Cardiac and pulmonary causes of dyspnoea--validation of a scoring test for clinical-epidemiological use: The study of men born in 1913. European heart journal. 1987;8:1007–1014. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the atherosclerosis risk in communities study) The American journal of cardiology. 2008;101:1016–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study: Methods and initial two years' experience. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1996;49:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosamond WD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Wang CH, McGovern PG, Howard G, Copper LS, Shahar E. Stroke incidence and survival among middle-aged adults: 9-year follow-up of the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) cohort. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1999;30:736–743. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones BL, Nagin D, Roeder K. A sas procedure based on mixture models for estimating developemental trajectories. Sociological methods & research. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2010;6:109–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling (nearly) two decades later. Journal of quantitative criminology. 2010;26:445–453. doi: 10.1007/s10940-010-9113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Jr., Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Murray KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW, Members AATF 2014 aha/acc/hrs guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: Executive summary: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. Circulation. 2014;130:2071–2104. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smit MD, Moes ML, Maass AH, Achekar ID, Van Geel PP, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Gelder IC. The importance of whether atrial fibrillation or heart failure develops first. European journal of heart failure. 2012;14:1030–1040. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McManus DD, Saczynski JS, Lessard D, Kinno M, Pidikiti R, Esa N, Harrington J, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and prognosis of patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation (the worcester heart failure study) The American journal of cardiology. 2013;111:1460–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jabre P, Roger VL, Murad MH, Chamberlain AM, Prokop L, Adnet F, Jouven X. Mortality associated with atrial fibrillation in patients with myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2011;123:1587–1593. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bengtson LG, Chen LY, Chamberlain AM, Michos ED, Whitsel EA, Lutsey PL, Duval S, Rosamond WD, Alonso A. Temporal trends in the occurrence and outcomes of atrial fibrillation in patients with acute myocardial infarction (from the atherosclerosis risk in communities surveillance study) The American journal of cardiology. 2014;114:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Neal WT, Sangal K, Zhang ZM, Soliman EZ. Atrial fibrillation and incident myocardial infarction in the elderly. Clinical cardiology. 2014;37:750–755. doi: 10.1002/clc.22339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healey JS, Connolly SJ. Atrial fibrillation: Hypertension as a causative agent, risk factor for complications, and potential therapeutic target. The American journal of cardiology. 2003;91:9G–14G. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aksnes TA, Kjeldsen SE, Schmieder RE. Hypertension and atrial fi brillation with emphasis on prevention. Blood pressure. 2009;18:94–98. doi: 10.1080/08037050903040744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Movahed MR, Hashemzadeh M, Jamal MM. Diabetes mellitus is a strong, independent risk for atrial fibrillation and flutter in addition to other cardiovascular disease. International journal of cardiology. 2005;105:315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huxley RR, Alonso A, Lopez FL, Filion KB, Agarwal SK, Loehr LR, Soliman EZ, Pankow JS, Selvin E. Type 2 diabetes, glucose homeostasis and incident atrial fibrillation: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Heart. 2012;98:133–138. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tadic M, Ivanovic B, Cuspidi C. What do we currently know about metabolic syndrome and atrial fibrillation? Clinical cardiology. 2013;36:654–662. doi: 10.1002/clc.22163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chamberlain AM, Agarwal SK, Folsom AR, Duval S, Soliman EZ, Ambrose M, Eberly LE, Alonso A. Smoking and incidence of atrial fibrillation: Results from the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study. Heart rhythm : the official journal of the Heart Rhythm Society. 2011;8:1160–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Baggett C, Johnson A, Bertoni AG, Shahar E, Deswal A, Heiss G, Chambless LE. Classification of heart failure in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (aric) study: A comparison of diagnostic criteria. Circulation. Heart failure. 2012;5:152–159. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.