Abstract

We investigated whether midlife pulse pressure is associated with brain atrophy and cognitive decline, and whether the association was modified by apolipoprotein-E ε4 (APOE-ε4) and hypertension. Participants (549 stroke- and dementia-free Framingham Offspring Cohort Study participants, age-range=55.0-64.9 years) underwent baseline neuropsychological and MRI (subset, n=454) evaluations with 5-7 year follow-up. Regression analyses investigated associations between baseline pulse pressure (systolic – diastolic pressure) and cognition, total cerebral volume and temporal horn ventricular volume (as an index of smaller hippocampal volume) at follow-up, and longitudinal change in these measures. Interactions with APOE-ε4 and hypertension were assessed. Covariates included age, sex, education, assessment interval, and interim stroke. In the total sample, baseline pulse pressure was associated with worse executive ability, lower total cerebral volume and greater temporal horn ventricular volume 5-7 years later, and longitudinal decline in executive ability and increase in temporal horn ventricular volume. Among APOE-ε4 carriers only, baseline pulse pressure was associated with longitudinal decline in visuospatial organization. Findings indicate arterial stiffening, indexed by pulse pressure, may play a role in early cognitive decline and brain atrophy in mid-to-late life, particularly among APOE-ε4 carriers.

Keywords: Pulse pressure, Cognition, APOE, Alzheimer's disease

Introduction

Substantial evidence suggests that midlife vascular risk factors, including hypertension, convey increased risk of later cognitive decline and dementia, independent of stroke1-3, and that these associations may be strengthened by the presence of the apolipoprotein-E ε4 allele (APOE-ε4).4 Beyond these traditional vascular risk factors, age-related arterial stiffening, quantified by brachial artery pulse pressure, central pulse pressure or carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity, has also been linked to cerebral atrophy5, cognitive decline6, 7 and dementia8, 9. Similar to traditional vascular risk factors, evidence suggests that the relationship between pulse pressure and cognitive decline may be modified by APOE genotype, potentially indicating an interactive effect on genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease (AD).10 Additional studies indicate that arterial stiffening may potentiate cerebral small vessel disease5, particularly in those with hypertension.11, 12 Thus, mounting evidence suggests that arterial stiffening may be an important component of the vascular contribution to dementia through its impact on brain atrophy and cerebrovascular disease, as well as interactions with other genetic and vascular risk factors for dementia.

Importantly, age-related arterial stiffening is also thought to be independent of traditional vascular risk factors, and may convey added risk of end-organ damage even in the absence of other health concerns.13 This is consistent with the hypothesis that these stiffening changes may play a role in the increased risk of dementia with age.14 In a series of recent studies, markers of arterial stiffening have demonstrated relationships with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of cerebral amyloidosis and tau-mediated neurodegeneration9, 15, 16, as well as cerebral amyloid retention on positron emission tomography (PET).15, 17, 18 Some evidence further suggests that the relationship between arterial stiffening and cerebral amyloid retention may be particularly salient in carriers of the APOE-ε4 allele.19 These findings suggest that arterial stiffening may contribute to AD pathophysiology, in addition to cerebrovascular disease, which may underlie the predictive utility of arterial stiffening in age-related cognitive decline.

In order to further evaluate the role of arterial stiffening in cognitive and brain aging, the current study investigated whether brachial artery pulse pressure, a simple and clinically available index of arterial stiffness, was predictive of cognitive and atrophic brain changes over a 5-7 year period. This longitudinal study focused on a subset of the Framingham Offspring Cohort with relatively few health concerns, during the transition from mid- to late-life (ages 55-64 at baseline), with the aim of providing information on early cognitive and brain changes potentially indicative of future dementia risk. The study also examined interactions with genetic risk for AD, by investigating the potential role of the APOE-ε4 in modifying the predictive value of baseline pulse pressure. It was hypothesized that pulse pressure would predict cerebral and hippocampal atrophy, and neuropsychological decline, even in the absence of any evidence of subcortical ischemic white matter disease. It was further hypothesized that these changes would be more prominent in those carrying the APOE-ε4 allele.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The Framingham Heart Study is a community-based, prospective study aimed at identifying risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Participants in the current study were a subset of the Offspring Cohort who were of older middle age at baseline (55-64 years) and in good health. Participants underwent health examination between 1998 and 2001, and 2 neuropsychological assessments ≥5 years apart (first assessment, 1999-2003, and second assessment, 2004-2009). Three blood pressure measures were obtained within a 15-20 minute time period (twice from the left arm and once from the right arm) during the health exam. These were averaged to obtain systolic and diastolic blood pressure estimates, and pulse pressure was calculated as the difference between these measures (systolic – diastolic pressure). Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or greater, diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or greater, or use of antihypertensive medications.20 Participants were classified into three blood pressure groups: normal (SBP <120 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg), prehypertension (SBP 120-139 mm Hg or DBP 80-89 mm Hg), and hypertensive (SBP≥140 mm Hg or DBP≥90 mm Hg or antihypertensive treatment). Those in the normal or prehypertension groups were not taking antihypertensive medications. Among 1242 participants aged 55-64 years who were examined, the following exclusions were made: prevalent clinical stroke (n=8), prevalent dementia (n=0), missing blood pressure (n=3), missing neuropsychological assessment (n=665), <5 year interval between neuropsychological assessments (n=8), missing APOE status (n=13), other neurological conditions that could impact cognitive test scores (n=18). No participants were demented. Final total sample was 549 participants. A subset of 454 participants also underwent brain MRI concurrent with baseline and follow-up neuropsychological evaluations.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Standardized neuropsychological measures administered at both assessments included measures of verbal memory (Wechsler Memory Scale [WMS] Logical Memory–delayed free recall [LM-delayed]), visual memory (WMS Visual Reproduction–delayed free recall [VR-delayed]), attention and executive functioning (Halstead–Reitan Trail Making Test Part A [Trails A] and Part B [Trails B]), visuospatial organization or non-motor executive visuoconstructional skills (Hooper Visual Organization Test)21-23, and language (Boston Naming Test 30-item version [BNT]). For the Trail Making Test, a difference score (i.e., Trails B-A) was calculated. This derived score may reflect a purer measure of the executive abilities required to complete Trails B by subtracting out the simple sequencing, visual scanning, and psychomotor demands common to both Trails A and B.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Neuroanatomic Regions of Interest

The MRI techniques used in the FHS Offspring Study have been described previously.24 Briefly, participants were scanned on a 1.5-T Siemens Magnetom. All images were read by individuals who were blinded to any demographic or clinical information including age and parental dementia status. From T1-weighted scans, we computed total cerebral brain volume (TCBV) and the volume around the temporal horns (temporal horn volume [THV]), which served as a surrogate measure of hippocampal volume with greater THV being proportional to smaller hippocampal volume.24 T2-Weighted double spin-echo coronal sequences were also acquired in 4-mm contiguous slices and used to quantify total white matter hyperintensity volume (WMHV). All volumetric measures were calculated as a percentage of total cranial volume to correct for differences in head size.25

Statistical Analyses

Outcome variables were natural log (ln) transformed to improve normality, as needed. Annualized raw change on neuropsychological and MRI measures was calculated as follows: ([score at the second assessment minus score at the first assessment]/[time between the first and second assessments in years]). Signs of Trail Making Test variables were reversed during calculation of annual rate of change to be consistent with the other neuropsychological measures (i.e., negative rate of change indicates decline).

Multivariable linear regression models were constructed to examine the association between baseline pulse pressure and brain volume and performance on neuropsychological tests 5-7 years later, as well as annualized change in brain volume (TCBV and THV), WMHV, and neuropsychological performance. All analyses were adjusted for age at blood pressure measurement, sex, education group (<high school degree, high school degree, some college, ≥college degree), and time (years) from blood pressure assessment to the first neuropsychological assessment. Beta coefficients from the linear regression models represent the effect on neuropsychological measures or percent brain volume per mm Hg of pulse pressure after covariate adjustment. Interactions with APOE-ε4 carrier status and blood pressure were also evaluated by the inclusion of a cross-product term in the model. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for main effects. Stratified analysis results were presented for all instances where the p-value for interaction was <0.05. Given the exploratory nature of the study, correction for multiple comparisons was not applied. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the sample participants at the time baseline pulse pressure was measured. Characteristics of participants who were not included in the study sample due to lack of neuropsychological testing are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Overall, participants who were excluded from the study sample had lower education levels, higher pulse pressure, and a higher prevalence of hypertension.

Table 1.

Study sample characteristics.

| N= 549 | |

|---|---|

| Age at blood pressure measurement, years | 59.6 (2.7) |

| Women, n (%) | 292 (53.2) |

| Education group, n (%) | |

| <HS degree | 12 (2.2) |

| HS degree | 149 (27.1) |

| Some college | 190 (34.6) |

| ≥College degree | 198 (36.1) |

| APOE-ε4 carrier, n (%) | 126 (23.0) |

| Pulse pressure, mm Hg | 50 (12) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 124 (16.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75 (9.0) |

| Blood pressure group, n (%) | |

| Normal | 166 (30.2) |

| Prehypertension | 175 (31.9) |

| Hypertension | 208 (37.9) |

| Time between blood pressure measure and baseline NP, years | 0.6 (0.5) |

| Time between initial and follow-up NP, years | 6.6 (0.8) |

| Neuropsychological test measures (at follow-up visit) | |

| LM-delayed | 11.4 (3.7) |

| VR-delayed | 8.2 (3.1) |

| Similarities | 17.2 (3.5) |

| Trails A, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 0.47 (0.38, 0.60) |

| Trails B-A, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 0.75 (0.55, 1.07) |

| Boston Naming Test, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 28 (26, 29) |

| Hooper Visual Organization Test, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 25.5 (24.0, 27.0) |

| MRI brain measures (at follow-up visit) | N=454 |

| Total cerebral brain volume, % | 79.2 (3.0) |

| Temporal horn volume, %, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 0.048 (0.026, 0.076) |

| White matter hyperintensities volume, %, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 0.081 (0.044, 0.16) |

Note: Data presented as mean (standard deviations) unless otherwise indicated. MRI brain measures are presented as a percentage of total cranial volume.

Neuropsychological Test Outcomes

Across all participants, higher baseline pulse pressure was associated with worse performance on a test of executive functioning (Trails B-A) at 5-7 year follow-up, p = .02 (Table 2A), as well as greater annualized decline in performance on this test over the follow-up interval, p = .03 (Table 2B). There were no statistically significant interactions between pulse pressure and blood pressure group for any of the neuropsychological test outcomes.

Table 2.

Regression results for baseline pulse pressure predicting cognition at 5-7 year follow-up and annualized change in cognition, as well as interactions with the APOE-ε4 carrier status and blood pressure group.

| A Time 2 Performance | Pulse Pressure (mm Hg) Main Effects | Blood pressure group* Interaction | APOE-ε4 status Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (SE) | P | P | P | |

| LM-delayed | -0.0018 (0.013) | 0.89 | 0.08 | 0.48 |

| VR-delayed | -0.018 (0.011) | 0.10 | 0.74 | 0.09 |

| Similarities | 0.0017 (0.011) | 0.88 | 0.60 | 0.16 |

| Trails A** | -0.0017 (0.0012) | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.22 |

| Trails B-A** | -0.0015 (0.00068) | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.66 |

| BNT** | 0.0021 (0.0022) | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.42 |

| HVOT** | -0.0021 (0.0018) | 0.25 | 0.63 | 0.26 |

| B | ||||

| Time 2-1 Performance | Beta (SE) | P | P | P |

| LM-delayed | -0.00085 (0.0020) | 0.67 | 0.11 | 0.49 |

| VR-delayed | -0.00045 (0.0017) | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.78 |

| Similarities | -0.0010 (0.0018) | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.18 |

| Trails A | -0.000014 (0.00011) | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.68 |

| Trails B-A | -0.00098 (0.00045) | 0.03 | 0.65 | 0.30 |

| BNT | -0.000052 (0.00081) | 0.95 | 0.34 | 0.08 |

| HVOT | -0.00012 (0.0012) | 0.92 | 0.70 | 0.004 |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; LM, logical memory; VR, visual reproductions; BNT, Boston Naming Test; HVOT, Hooper Visual Organization Test

Normal is SBP <120 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg, prehypertension is SBP 120-139 mm Hg or DBP 80-89 mm Hg, hypertension is SBP≥140 mm Hg or DBP≥90 mm Hg or anti hypertensive treatment

Natural log transformed.

Note: All models are adjusted for age at pulse pressure measurement, sex, education group, years between pulse pressure measurement and follow-up neurospsychological testing, and prevalent stroke at follow-up neurospsychological testing. Trails A, Trails B-A, HVOT, and BNT raw scores were transformed using natural log. Signs were inverted for Trails A and Trails B-A so that the direction of effects is consistent across all measures.

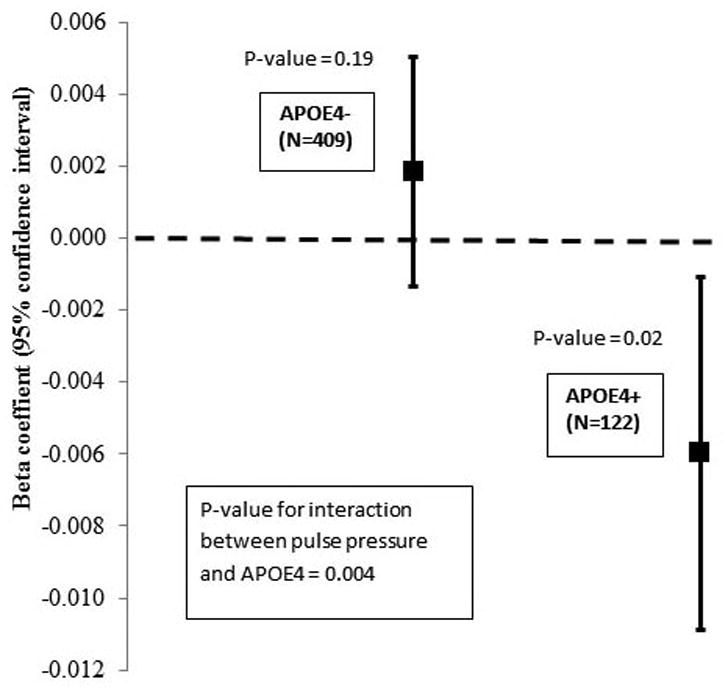

Regarding APOE-ε4 carrier status, interaction analyses suggested potential differences in the relationship between pulse pressure and longitudinal change in visuospatial organization over the follow-up interval (HVOT; Table 3). Stratified analyses indicated that among APOE-ε4 carriers, higher baseline pulse pressure was associated with greater decline in visuospatial organization ability over follow-up, β = -0.006, p = 0.02 (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Summary of statistically significant interactions (p-value<0.05) between pulse pressure and APOE-ε4 carrier status and blood pressure group for cognitive outcomes.

| Time 2-1 Performance | Stratification Group | N | Pulse Pressure (mm Hg) Main Effects | P-value for interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (SE) | P | ||||

| HVOT | APOE-ε4 status | 0.004 | |||

| No | 409 | 0.0019 (0.0014) | 0.19 | ||

| Yes | 122 | -0.0060 (0.0025) | 0.02 | ||

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; HVOT, Hooper Visual Organization Test

Note: All models are adjusted for age at pulse pressure measurement, sex, education group, and years between pulse pressure measurement and follow-up neuropsychological testing. There was insufficient sample size in the stratified analysis to adjust for prevalent stroke at follow-up neuropsychological testing.

Figure 1.

Association between pulse pressure and annualized change in HVOT, stratified by APOE4. Beta coefficients are displayed for the association between pulse pressure and HVOT performance among APOE-ε4 noncarriers (APOE4-) and carriers (APOE4+). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for beta coefficients.

MRI Brain Outcomes

Higher baseline pulse pressure was associated with smaller TCBV, p = .01, and larger THV (indexing smaller hippocampal volume), p = .01, at follow-up (Table 4A), as well as greater increase in THV over the follow-up interval, p = .03 (Table 4B). There were no statistically significant interactions between pulse pressure and either hypertensive status or APOE-ε4 carrier status for any MRI measure (Table 4A-B). Participants showed little white matter disease on MRI at follow-up (median=0.081%, 25th percentile = 0.044%, 75th percentile= 0.16%) and pulse pressure was not associated with total WMHV in any analyses (all p's > .05).

Table 4.

Regression results for baseline pulse pressure predicting MRI measures at 5-7 year follow-up and annualized change in MRI measures, as well as interactions with the APOE-ε4 carrier status and blood pressure group.

| A Time 2 MRI measures | Pulse Pressure (mm Hg) Main Effects | Blood pressuregroup* Interaction | APOE-ε4 status Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (SE) | P | P | P | |

| Total Cerebral Brain Volume | -0.00028 (0.00011) | 0.01 | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| Temporal Horn Volume** | 0.0077 (0.0031) | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.81 |

| White Matter Hyperintensities Volume** | 0.0015 (0.0041) | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

| B | ||||

| Time 2-1 MRI measures | Beta (SE) | P | P | P |

| Total Cerebral Brain Volume | -0.023 (0.014) | 0.09 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| Temporal Horn Volume | 0.00059 (0.00027) | 0.03 | 0.84 | 0.36 |

| White Matter Hyperintensities Volume | 0.0018 (0.0010) | 0.09 | 0.95 | 0.87 |

Normal is SBP <120 mm Hg and DBP <80 mm Hg, prehypertension is SBP 120-139 mm Hg or DBP 80-89 mm Hg, hypertension is SBP≥140 mm Hg or DBP≥90 mm Hg or anti hypertensive treatment

Natural log transformed.

Note: All models are adjusted for age at pulse pressure measurement, sex, education group, years between pulse pressure measurement and follow-up MRI, and prevalent stroke at follow-up MRI. All MRI measures were analyzed as percent of total intracranial volume.

Discussion

We hypothesized that arterial stiffening, indexed by higher pulse pressure, may accelerate cognitive decline in middle-age to young-old adults, and that this effect may be further potentiated by the presence of hypertension and the APOE-ε4 allele. Consistent with this hypothesis, the present study findings indicated that increased pulse pressure during the transition from middle to young-old age was associated with decline on a measure of executive function, even in the absence of significant white matter lesion pathology. This finding is also consistent with extensive evidence that vascular dysfunction and disease impacts executive abilities26, 27, and further suggests that these changes may be independent of subcortical small vessel disease observable on MRI.28 Executive abilities show expected declines as part of “normal” cognitive aging.23, 29. The results of the present study could also suggest that these declines may occur in part due to age-related arterial stiffening and its hemodynamic consequences. Importantly, findings were significant even after controlling for age, suggesting that arterial stiffness may also further contribute to executive decline beyond that observed as part of normal aging.

The current study further revealed that participants at genetic risk for AD due to presence of the APOE-ε4 allele displayed additional relationships between pulse pressure and visuospatial organization. Our test of visuospatial organization, the HVOT, assesses primarily executive and visuospatial domains, requiring mental rotation and reconstruction of disassembled line drawings, but also requires naming ability.21, 23 Thus, it remains unclear exactly which of these abilities was most related to pulse pressure, but the involvement of both visual memory and visuospatial organization may suggest that arterial stiffening has broader implications for cognitive decline among APOE-ε4 carriers than noncarriers. This is consistent with a growing body of research suggesting that vascular vulnerability factors may interact with genetic risk related to APOE-ε4 in conveying increased risk of cognitive decline.4

Pulse pressure was not associated with white matter hyperintensities in this stroke-free sample with relatively low vascular risk factor burden, suggesting that relationships with cognitive decline were not due solely to observable cerebrovascular disease. Higher baseline pulse pressure was associated with smaller cerebral volume and was predictive of hippocampal atrophy, indexed by increased ventricular volume in the temporal horn. Together these findings could point to a neurodegenerative mechanism linking pulse pressure to cognitive decline. This is consistent with prior work demonstrating associations between pulse pressure elevation and both cerebral amyloidosis30 and tau-mediated neurodegeneration9, 15, and other findings indicating that arterial stiffening predicts longitudinal change in cerebral amyloid retention.17, 18 We hypothesize that arterial stiffening may accelerate cognitive decline, particularly among carriers of the APOE-ε4 allele.

The observed relationships between pulse pressure and indicators of cognitive decline and brain atrophy may have treatment implications. Studies investigating the influence of antihypertensive medications on cognitive decline and brain atrophy have yielded mixed results.31-33 This may be due to the great variety of available medications which work through several distinct physiological pathways. Some antihypertensive medicines exhibit “destiffening effects” that can reduce indicators of arterial stiffening independent of their effects on systolic, diastolic and mean pressures.34 Among these destiffening medicines, those impacting the renin angiotensin system, particularly angiotensin II AT1-receptor blockers (ARBs), have also shown benefit for cognitive decline.35 Thus, use of ARBs or other destiffening medications may exert potential benefits partly through modification of arterial stiffening and its hemodynamic consequences.

Strengths of the current study include its longitudinal design and inclusion of both neuropsychological and MRI measures in a large sample of community dwelling adults transitioning from midlife to young-old age. Although the study findings indicated a small effect size, this may largely be due to the fact that participants were relatively healthy with very limited vascular risk and cerebrovascular disease burden. Indeed these aspects of our study sample underscore the potential importance of arterial stiffness in the slow, insidious process of cognitive and brain aging, even in the context of relatively good cognitive and cerebrovascular health. The large sample size also allowed investigation of important interaction effects for APOE-ε4 carrier status and history of hypertension. Study limitations include the lack of molecular markers for neurodegenerative disease. Additionally, given the exploratory nature of the study, correction for multiple comparisons was not applied. Moreover, since the study sample was predominantly white coupled with an age range of 55-64 years, the generalizability of our results to other populations is uncertain. Future studies should seek to replicate these findings in more diverse samples. Future studies should also further elucidate the mechanisms linking increased pulse pressure to later cognitive decline and cerebral atrophy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Framingham Heart Study's National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contract (N01-HC-25195), by grants (R01-AG16495, R01-AG08122) from the National Institute on Aging, and by grant (R01-NS17950) from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

References

- 1.Qiu C, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The age-dependent relation of blood pressure to cognitive function and dementia. The Lancet Neurology. 2005;4:487–499. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polidori MC, Pientka L, Mecocci P. A review of the major vascular risk factors related to Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2012;32:521–530. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skoog I, Lernfelt B, Landahl S, et al. 15-year longitudinal study of blood pressure and dementia. Lancet. 1996;347:1141–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangen KJ, Beiser A, Delano-Wood L, et al. APOE genotype modifies the relationship between midlife vascular risk factors and later cognitive decline. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:1361–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsao CW, Seshadri S, Beiser AS, et al. Relations of arterial stiffness and endothelial function to brain aging in the community. Neurology. 2013;81:984–991. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a43e1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nation DA, Wierenga CE, Delano-Wood L, et al. Elevated pulse pressure is associated with age-related decline in language ability. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 2010;16:933–938. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waldstein SR, Rice SC, Thayer JF, Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Zonderman AB. Pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity are related to cognitive decline in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Hypertension. 2008;51:99–104. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu C, Winblad B, Viitanen M, Fratiglioni L. Pulse pressure and risk of Alzheimer disease in persons aged 75 years and older: a community-based, longitudinal study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2003;34:594–599. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000060127.96986.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nation DA, Edmonds EC, Bangen KJ, et al. Pulse pressure in relation to tau-mediated neurodegeneration, cerebral amyloidosis, and progression to dementia in very old adults. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:546–553. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFall GP, Wiebe SA, Vergote D, et al. ApoE and pulse pressure interactively influence level and change in the aging of episodic memory: Protective effects among epsilon2 carriers. Neuropsychology. 2015;29:388–401. doi: 10.1037/neu0000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kearney-Schwartz A, Rossignol P, Bracard S, et al. Vascular structure and function is correlated to cognitive performance and white matter hyperintensities in older hypertensive patients with subjective memory complaints. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40:1229–1236. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.532853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poels MM, Zaccai K, Verwoert GC, et al. Arterial stiffness and cerebral small vessel disease: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:2637–2642. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.642264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell GF. Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: implications for end-organ damage. Journal of applied physiology. 2008;105:1652–1660. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90549.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabkin SW. Arterial stiffness: detection and consequences in cognitive impairment and dementia of the elderly. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2012;32:541–549. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nation DA, Edland SD, Bondi MW, et al. Pulse pressure is associated with Alzheimer biomarkers in cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. 2013;81:2024–2027. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436935.47657.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nation DA, Edmonds EC, Bangen KJ, et al. Pulse Pressure in Relation to Tau-Mediated Neurodegeneration, Cerebral Amyloidosis, and Progression to Dementia in Very Old Adults. JAMA Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes TM, Kuller LH, Barinas-Mitchell EJ, et al. Pulse wave velocity is associated with beta-amyloid deposition in the brains of very elderly adults. Neurology. 2013;81:1711–1718. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000435301.64776.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes TM, Kuller LH, Barinas-Mitchell EJ, et al. Arterial stiffness and beta-amyloid progression in nondemented elderly adults. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:562–568. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigue KM, Rieck JR, Kennedy KM, Devous MD, Sr, Diaz-Arrastia R, Park DC. Risk factors for beta-amyloid deposition in healthy aging: vascular and genetic effects. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:600–606. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. Jama. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferson AL, Wong S, Bolen E, Ozonoff A, Green RC, Stern RA. Cognitive correlates of HVOT performance differ between individuals with mild cognitive impairment and normal controls. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;21:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms, and commentary. 2nd. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Libon DJ, Glosser G, Malamut BL, et al. Age, executive functions and visuospatial functioning in healthy older adults. Neuropsychology. 1994;8:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeCarli C, Massaro J, Harvey D, et al. Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the framingham heart study: establishing what is normal. Neurobiology of aging. 2005;26:491–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, et al. Stroke risk profile, brain volume, and cognitive function: the Framingham Offspring Study. Neurology. 2004;63:1591–1599. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142968.22691.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamar M, Price CC, Giovannetti T, Swenson R, Libon DJ. The dysexecutive syndrome associated with ischaemic vascular disease and related subcortical neuropathology: a Boston process approach. Behav Neurol. 2010;22:53–62. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2009-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Libon DJ, Drabick DA, Giovannetti T, et al. Neuropsychological syndromes associated with Alzheimer's/vascular dementia: a latent class analysis. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2014;42:999–1014. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng L, Mack WJ, Chui HC, et al. Coronary artery disease is associated with cognitive decline independent of changes on magnetic resonance imaging in cognitively normal elderly adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60:499–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindenberger U. Human cognitive aging: corriger la fortune? Science. 2014;346:572–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1254403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langbaum JB, Chen K, Launer LJ, et al. Blood pressure is associated with higher brain amyloid burden and lower glucose metabolism in healthy late middle-age persons. Neurobiology of aging. 2012;33:827, e811–829. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu C. Preventing Alzheimer's disease by targeting vascular risk factors: hope and gap. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2012;32:721–731. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters R, Beckett N, Forette F, et al. Incident dementia and blood pressure lowering in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2008;7:683–689. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staessen JA, Thijs L, Richart T, Odili AN, Birkenhager WH. Placebo-controlled trials of blood pressure-lowering therapies for primary prevention of dementia. Hypertension. 2011;57:e6–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.165142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Vascular Mechanism C. Dose-dependent arterial destiffening and inward remodeling after olmesartan in hypertensives with metabolic syndrome. Hypertension. 2014;64:709–716. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levi Marpillat N, Macquin-Mavier I, Tropeano AI, Bachoud-Levi AC, Maison P. Antihypertensive classes, cognitive decline and incidence of dementia: a network meta-analysis. Journal of hypertension. 2013;31:1073–1082. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283603f53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.