Abstract

Noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) is the response-independent delivery of a reinforcer (Vollmer, Iwata, Zarcone, Smith, and Mazaleski in Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 26: 9–21 1993). Two staff members (preservice education majors) implemented NCR procedures for two students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who exhibited problem behavior and attended an after-school program. The amount of training on NCR and procedural fidelity was measured for each staff member, and the effects of the treatment on problem behavior were evaluated. Results indicate NCR is a low-effort procedure that reduced problem behavior of two participants with ASD.

• NCR can both reduce problem behaviors of clients who engage in difficult behaviors (Carr, Severtson, & Lepper, 2009).

• NCR can be used for clients for whom extinction-induced behaviors are dangerous (Tucker, Sigafoos, and Bushell in Behavior Modification, 22: 529–547, 1998).

• Nonbehavioral providers can implement NCR with high fidelity, making it a good procedure to use when collaborating with other professionals (teachers, SLP, parents, etc.; Matson, 2009).

• NCR can be used when clinicians first begin working with a client until more detailed interventions are created.

Keywords: Noncontingent reinforcement, Autism Spectrum Disorders

Noncontingent reinforcement (NCR), delivering a reinforcer independent of a target response (Carr, Severtson, & Lepper, 2009), has been used to decrease a number of problem behaviors, such as self-injurious behavior (Vollmer, Iwata, Zarcone, Smith, & Mazaleski, 1993), aggression (Vollmer et al., 1993), and destructive behavior (Hagopian, Fisher, & Legacy, 1994), as well as to increase appropriate behaviors such as on-task behavior (Riley et al., 2011; Austin & Soeda, 2008).

NCR has several advantages in applied settings. First, NCR is relatively easy to implement (Hagopian, Fisher, & Legacy, 1994; O’Callaghan, Allen, Powell, & Salama, 2006). Studies have shown that care providers can successfully implement NCR with subsequent positive effects (Matson, 2009). A second advantage of NCR is that it can attenuate extinction-induced increase in problem behavior, (i.e., extinction bursts; Hagopian et al., 1994). Finally, NCR can be used as an initial intervention for staff allowing them time to develop more detailed interventions. NCR may also be a way to initially reduce problem behaviors to a level which allows staff to more easily teach and reinforce the appropriate behaviors.

NCR is a promising behavioral intervention; however, dimensions of this procedure require further study. First, there are currently no studies that have investigated the type of training required for implementers of NCR to perform the procedure with high fidelity. Although many studies report the procedural fidelity with which NCR is implemented, assessments of training protocols are not provided. Second, other studies utilize implementers who are likely experienced with behavioral interventions. The extent to which NCR can be implemented with high fidelity by professionals who do not commonly utilize behavior interventions is still unknown. For these reasons, this study included the following objectives: (a) to determine whether and to what extent NCR procedures can be used to decrease problem behaviors in two students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in a group after-school setting and (b) to determine whether and to what extent after-school staff (preservice education majors) can implement the NCR procedures through video modeling and corrective feedback.

Setting and Materials

This study was conducted in a university-sponsored after-school setting for students with ASD. The program was operated from Monday to Friday. Students attended either Monday or Wednesday for 1.5 h, Tuesday or Thursday for 1.5 h, or Friday for 3 h. The program followed a schedule of planned activities including music and movement, social skill instruction, games, and crafts. The staff of the program consisted of undergraduate students interested in pursuing a career in special education or a related field.

Participants

Students

Two participants with ASD were chosen for this study because they engaged in high levels of attention-maintained problem behavior that was interfering with their ability to engage with the after-school program. They were in different classes of the program and had different staff. Prior to the intervention, each participant’s problem behavior was occurring at a level of intensity that required one of the two staff persons in the room to act as a 1:1 aide. Thus, the other staff person was responsible for the remaining students in the class. This also resulted in each participant being on an individualized schedule that resulted in less engaged academic programming, namely the social skill curriculum time of the day. A Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) conducted a function-based assessment (FBA) to identify the function of each participant’s problem behavior. The BCBA used a functional assessment interview (Dunlap et al., 1993) to elicit information from staff, program director, and participant caregivers regarding the participant’s behavior. The BCBA then conducted direct observation of the participant in the after-school setting in different increments measuring a total of 4 h for each participant. The results of the FBA suggested that attention was the function of the problem behavior for each participant.

The first participant was Frank, a 10-year-old male diagnosed with ASD. He attended the after-school program 2 days a week and received speech therapy after school for 2 days a week. In the after-school program, Frank was in a class with eight other males with ASD ranging from 6 to 11 years of age.

The second participant was Charlie, a 12-year-old male diagnosed with ASD. He attended the after-school program 2 days a week. Charlie was in class with four other males with ASD ranging from 11 to 13 years of age.

Staff

The staff participants were chosen because they were the staff in the classroom with the participants with ASD. There were two staff in each classroom, and one staff was chosen randomly from each room to participate in the study. The first staff participant was Sarah. She was an undergraduate student in special education in her Junior year at a local university. She was majoring in special education and had one 3-h course in Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). Sarah had worked at this after-school program for 1 year prior to the study and had never implemented NCR prior to the study.

The second participant was Hank. Hank was also a Junior special education major at a local university. He also had one 3-h course on ABA. Hank had worked at the after-school program for 1.5 years prior to the study and had never implemented NCR.

Data Collection, Interobserver Agreement, and Procedural Fidelity

Problem Behavior

Both participants engaged in negative talk and property destruction that severely limited their ability to interact with their teachers and peers.

Negative talk was defined as negative statements or vocalizations (e.g., mock statements, whining, complaining, tattling, or making fun of another person). This category also included threats of physical aggression against a person or property, arguing with another person (as in protest) as well as any verbal refusal to comply with a command from the teacher. Negative talk was coded separately if at least 5 s passed between the end of one statement and the beginning of another. Property destruction was defined as throwing, breaking, tearing, or other actions that destroyed classroom property. Property destruction was coded separately if at least 5 s passed between the end of one incident and the beginning of another.

Measurement System

Observers used pen-and-pencil event-based recording to measure disruptive behavior and noncontingent reinforcement statements. All sessions were videotaped and later coded by two independent observers.

Interobserver Agreement

Two observers simultaneously but independently collected data during 42 % of the sessions. Interobserver agreement (IOA) was measured as the total number of agreement plus the total number of disagreement divided by the total behaviors for each session. These totals were then averaged. IOA for Frank averaged 93 % for negative talk (Range = 82–100 %) and 86 % for property destruction (Range = 63–100 %). IOA for Charlie averaged 100 % for negative talk and 97 % for property destruction (Range = 85–100 %).

IOA was collected for 35 % of sessions. To calculate IOA for staff procedural fidelity, both observers’ data were compared, and the number of events that fell within ±5 s of each other (agreements) was divided by the total number of events recorded by either observer (agreements and disagreements); then, the quotient was multiplied by 100 %. IOA for procedural fidelity averaged 90 % for Sarah (Range = 80–100 %) and 96 % for Hank (Range = 90–100 %).

Procedural Fidelity

Procedural fidelity was measured as either an occurrence or nonoccurrence of appropriately delivered NCR. To be coded as an appropriate NCR delivery, the staff had to meet two criteria: (a) a neutral statement was made within 5 s of the 1-min-timed interval and (b) the statement was directed explicitly to the participant. Procedural fidelity was collected during 100 % of intervention sessions. Any comment that was directed to the class as a whole, a praise statement or reprimand, or fell outside the 5-s mark was considered to be an inaccurate NCR.

Training

A BCBA conducted one training session prior to the initial baseline phase with each staff member in the study. The training sessions lasted approximately 1 h. The training included a PowerPoint discussion of why NCR was a promising intervention, a 10-min video of a staff member modeling the NCR procedure in different settings, and a 10-min mock practice session with corrective feedback. During the training, the researcher and staff brainstormed examples and non examples of NCR statements that could be used. At the end of the training, staff were given a brief quiz about how to implement NCR. The staff member was taught to use NCR on a fixed-time schedule by using a MotivAider® to prompt NCR during classroom instruction. During the 10-min mock practice session, the staff member was considered trained if he/she could correctly give a neutral statement on a 1-min schedule with 80 % accuracy.

Prior to intervention, the schedule of reinforcement was determined by calculating the average rate of which the student was given teacher attention in the form of either praise or reprimands during baseline observations (number rounded to the nearest minute). For both participants, the schedule was determined to be a fixed-time (FT) 1-min schedule of reinforcement.

Design

An ABAB design was utilized to evaluate the effects of NCR on problem behavior. Conditions included a baseline condition and NCR condition.

Intervention

Baseline

When training was complete and the schedule was chosen, the data collection began on the first baseline phase. During baseline, staff did not use the Motivator® and were directed to engage in the typical instruction that was occurring prior to the training.

NCR

Following baseline conditions in which consistent levels of problem behavior were observed, the NCR condition was implemented. During NCR, the program activities were identical to baseline. The only change occurred during the 10-min segment of social skills instruction. The observer signaled to the staff that the videotape was beginning, and the staff set the MotivAider® to a FT 1-min schedule. The staff member was told to provide NCR on a FT 1-min schedule to the participant.

Results

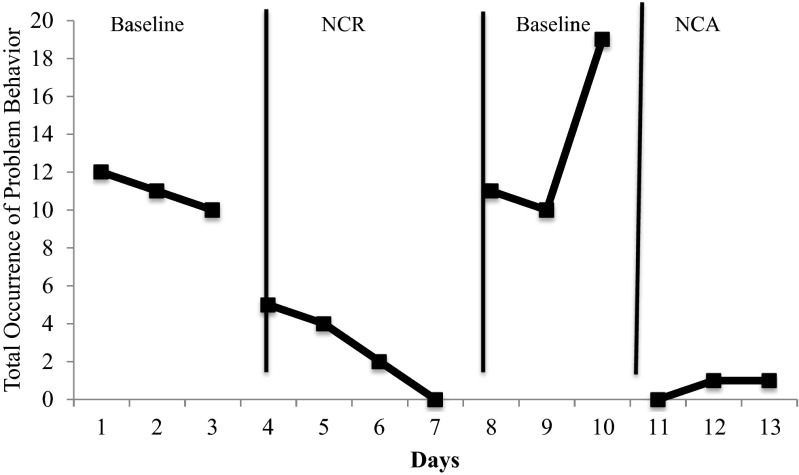

Frank’s problem behaviors are presented in Fig. 1. During baseline, occurrences of problem behavior were relatively frequent (M = 11), but decreased during the NCR phase (M = 2.8). When NCR was withdrawn, high frequencies of problem behavior returned (M = 13.3). Levels again reduced to near zero frequencies with the reintroduction of the NCR condition (M = 0.7).

Fig. 1.

Frank’s total problem behavior

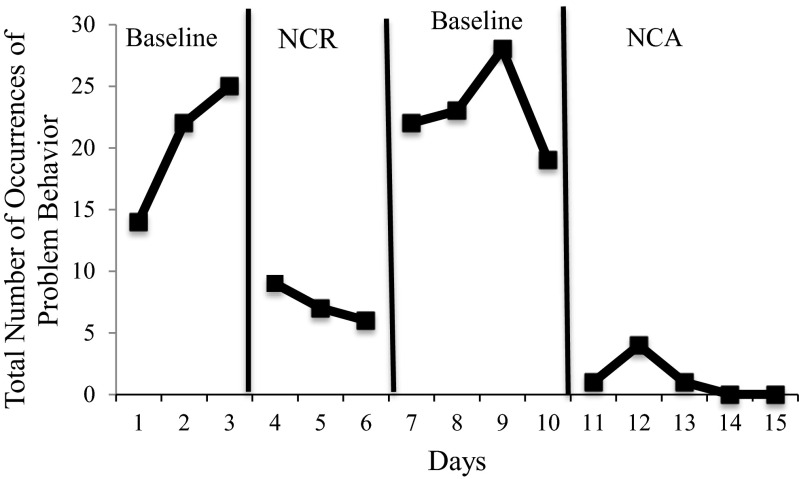

Charlie’s problem behaviors are presented in Fig. 2. During baseline, occurrences of problem behavior were relatively frequent (M = 20.3), but decreased during the NCR condition (M = 7.3). When NCR was withdrawn, high frequencies of problem behavior returned (M = 23). Levels again reduced when NCR was reintroduced (M = 1.2). Overall, these results suggest that NCR consisting of attention effectively reduced problem behavior for both Frank and Charlie.

Fig. 2.

Charlie’s total problem behavior

Procedural fidelity for Sarah and Hank are presented in Table 1. Sarah’s procedural fidelity averaged 96.6 % (Range = 90–100 %) and Hank’s averaged 95 % (Range = 90–100 %). Thus, they both implemented the intervention with a high level of fidelity.

Table 1.

Procedural fidelity for NCR sessions for Sarah and Hank

| NCR session | Percentage of intervals of correctly delivered NCR statements for Sarah | Percentage of intervals of correctly delivered NCR statements for Hank |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90 | 100 |

| 2 | 100 | 90 |

| 3 | 100 | 90 |

| 4 | 100 | 100 |

| 5 | 100 | 100 |

| 6 | 90 | 100 |

Discussion and Implications for Practice

Results of the current study corroborate previous research on the positive impacts NCR can have on reducing problem behavior (e.g., Hagopian et al., 1994; Tomlin & Reed, 2012; Vollmer et al., 1993). The current study extends previous research by showing that NCR can be used with high fidelity by staff unfamiliar with behavioral interventions in an after-school setting. Additionally, the current results indicate that NCR can be used with specific students with negative behaviors effectively in a group setting when only the target students are receiving NCR. For practitioners, this study demonstrates the applicability of NCR in a setting that may be less structured than a typical classroom. Community-based programs are often staffed by non licensed educators. Therefore, it is important for behavior analytic researchers to evaluate the effects of various behavior analytic procedures in environments, such as classrooms, summer camp, after-school programs, and athletic teams. Additionally, using the procedures in settings with multiple participants suggests the potential applicability of this intervention to other inclusive community-based programs. Behavioral providers are often tasked with suggesting behavioral interventions that can be used broadly by staff and varied professionals and result in positive outcomes for individuals. An intervention with a high probability of fidelity may be a useful first step when training professionals on behavioral strategies. The current study illustrates that a basic training on NCR procedures can result in high levels of fidelity even among preservice teachers who have limited training in ABA or behavioral interventions.

Behavioral interventions that have shown to be promising in reducing problematic and disruptive behaviors are needed in both educational and inclusive community-based settings. NCR is one such promising intervention that can be implemented with relative ease across environments and as shown in this study, it can be implemented with targeted participants in a larger group setting. Additionally, this study supports the ease at which staff with little training in behavioral interventions can successfully implement NCR with high fidelity.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Austin JL, Soeda JM. Fixed-time teacher attention to decrease off-task behaviors of typically developing third graders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:279–283. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JE, Severtson JM, Lepper TL. Noncontingent reinforcement is an empirically supported treatment for problem behavior exhibited by individuals with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30:44–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Kern L, dePerczel M, Clarke S, Wilson D, Childs KE, et al. Functional analysis of classroom variables for students with emotional and behavioral challenges. Behavioral Disorders. 1993;18:275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Fisher WW, Legacy SM. Schedule effects of noncontingent reinforcement on attention-maintained destructive behavior in identical quadruplets. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:317–325. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL. Applied behavior analysis for children with autism spectrum disorders. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan PM, Allen KD, Powell S, Salama F. The efficacy of noncontingent escape for decreasing children’s disruptive behavior during restorative dental treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:161–171. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.79-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, McKevitt BC, Shriver MD, Allen KD. Increasing on-task behavior using teacher attention delivered on a fixed-time schedule. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2011;20:149–162. doi: 10.1007/s10864-011-9132-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin, M., & Reed, P. (2012). Effects of fixed-time reinforcement delivered by teachers for reducing problem behavior in special education classrooms. Journal of Behavioral Education, 21, 150–162. doi:10.1007/s10864-012-9147-z.

- Vollmer TR, Iwata BA, Zarcone JR, Smith RG, Mazaleski JL. The role of attention in the treatment of attention-maintained self-injurious behavior: noncontingent reinforcement and differential reinforcement of other behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:9–21. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]