Abstract

Background

Transpedicular screw fixation of the cervical spine provides excellent biomechanical stability. The feasibility of inserting a 3.5-mm screw in the pedicle requires a minimum pedicle diameter of 4.5 mm. This diameter allows at least 0.5 mm bony bridge medially and laterally in order to avoid pedicle violation which can result in neurovascular complications. We aim to evaluate the feasibility of this technique in Arab people since no data are available about this population.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study involved a retrospective review of computed tomography scans of normal cervical spines of 99 Arab adults. Ten morphometric measurements were obtained. Data were analyzed using a p value of ≤0.05 as the cut-off level of statistical significance.

Results

Our sample included 63 (63.6 %) males and 36 (36.4 %) females, with a mean age of 35.5 ± 16.5 years. The morphometric parameters of C3–C7 spine pedicles were larger in males than in females. The outer pedicle width (OPW) was <4.5 mm in >25 % of all subjects at C3–C6 vertebrae. Statistically significant differences in the OPW between males and females were noted at C3 (p = 0.032) and C6 (p = 0.004).

Conclusions

Inserting pedicle screws in the subaxial cervical spine is feasible among the majority of Arab people.

Level of evidence

Level 3.

Keywords: Pedicle, Cervical spine, Transpedicular fixation, Screw fixation, Computed tomography, Anatomy

Introduction

Numerous conditions of the cervical spine, such as trauma, deformities, tumors and osteoarthritis, require rigid fixation and solid fusion of the vertebral segments in order to achieve good treatment results. The most reliable and strongest technique for stabilization and immobilization of the spine is transpedicular screw fixation (TPSF) [1, 2]. Placing screws in the pedicles provides a better bony purchase compared to other techniques of spine fixation, leading to higher biomechanical stability [3, 4]. Nevertheless, TPSF of the cervical spine remains a difficult procedure due to the close proximity of the cervical pedicles to the vertebral artery, spinal cord and nerve roots [5, 6]. In addition, limited space is available for screw placement because of the complex anatomy of cervical spine vertebrae [7]. Therefore, the risk of complications due to screw violation of the adjacent vascular and neural structures is expected to be high when performing the operation without a clear understanding of the morphometric characteristics of the pedicles [8].

Morphometry of the cervical spine pedicles was studied before using cadavers and computed tomography (CT) scans [2, 9]. It was found that some morphometric measurements significantly differ across gender and race. This fact emphasizes the importance of studying pedicle morphometry across different populations in order to enhance the safety of TPSF surgery.

Regardless of numerous anatomical studies on cervical spine pedicles, the morphometry of this structure was never examined among Arab people. Therefore, we aim to obtain these measurements among this population in order to provide information that might help spine surgeons in fixing the cervical spines of Arab patients.

Materials and methods

Subjects and setting

This cross-sectional study involved a retrospective review of CT scans of the cervical spine obtained between January 2014 and December 2014 at Al-Amiri Hospital in Kuwait. Obtaining informed consent from involved patients was waived by our Research Ethics Committee. All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The study was approved by our local Research Ethics Committee. Inclusion criteria were patients aged at least 18 years, citizens of an Arab country, and no evidence of cervical spine congenital malformations, trauma, infection or tumor, as well as previous cervical spine surgery.

A 64-slice multidetector CT scanner (highspeed QX/i; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with a gantry rotation speed of 0.8 s per rotation was used. Images of the cervical spine were obtained while the patients were lying supine. The coverage area of scanning included the whole cervical spine, from the base of the skull down to the upper dorsal spine, scanned in the craniocaudal direction. Slice thickness of 5 mm, pitch of 1.5, table speed of 15 mm per rotation, reconstruction interval of 2 mm, tube voltage of 120 kV, and tube current of 200 mA were used for scanning. A picture archiving and communication system workstation monitor (IMPAX, DS3000; AGFA, Mortsel, Belgium) was used to review the transferred transverse CT scans as digital images. Coronal and sagittal multiplanar images were reconstructed. The morphometric parameters of the pedicles were measured from images of multiplanar reformations.

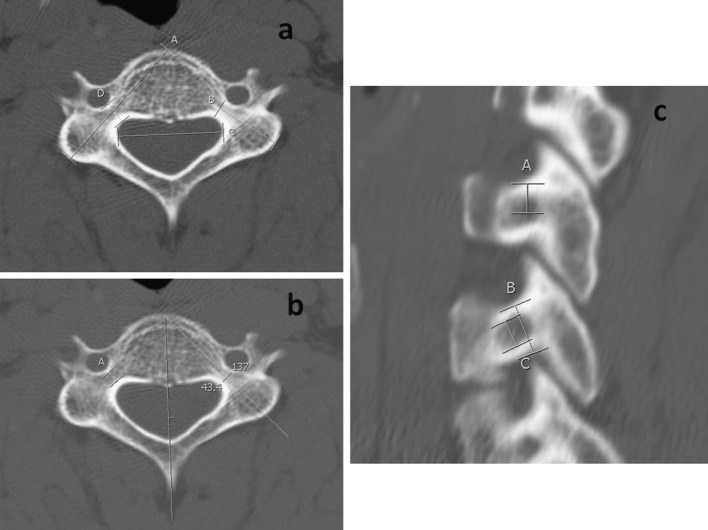

Ninety-nine patients were eligible for inclusion. Nine morphometric measurements were obtained for each pedicle, starting from C3 to C7, including both the right and left side (Table 1; Fig. 1). In addition to these measurements, the interpedicular distance (IPD) was also measured. The pedicle sagittal angle was not measured in our current study because of the variation in the technique of measuring this angle among previous investigators making it an unreliable measure [9–12].

Table 1.

Morphometric parameters of cervical spine pedicles

| Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

| Outer pedicle height | Outer superior to inferior diameter of the pedicle isthmus |

| Outer pedicle width | Outer medial to lateral diameter of the pedicle isthmus |

| Inner pedicle height | Superior to inferior diameter of the cancellous core of the pedicle isthmus |

| Inner pedicle width | Medial to lateral diameter of the cancellous core of the pedicle isthmus |

| Pedicle axis length | Distance from the posterior projective points of the pedicle axis on the lateral mass to the anterior margin of the vertebral body |

| Pedicle length | Distance from the posterior projective points of the pedicle axis on the lateral mass to the junction of the vertebral body and pedicle |

| Superior pedicle distance | Distance from the inferior edge of the superior facet to the posterior projective points of the pedicle axis on the lateral mass |

| Lateral pedicle distance | Distance from the lateral edge of the lateral mass to the posterior projective points of the pedicle axis on the lateral mass |

| Pedicle transverse angle | The angle between the pedicle axis projection and the anatomic sagittal plane |

| Interpedicular distance | Distance between the most medial point of the pedicle isthmus in the transverse plane |

Fig. 1.

Morphometric measurements of the subaxial cervical spine pedicle. a Axial image of C4 vertebra on computed tomography scan showing the pedicle axis length (A), pedicle length (B), interpedicular distance (C) and outer pedicle width (D). b Axial image of C4 vertebra on computed tomography scan showing the inner pedicle width (A) and transverse angle, which in this particular case was 43.4°. c Sagittal reconstruction image of the cervical spine at the level of C3 and C4 showing the superior pedicle distance (A), outer pedicle height (B) and inner pedicle height (C)

A total of 990 pedicles (198 pedicles at each vertebral level) were evaluated in this study. In order to assess the intra-observer repeatability and inter-rater reproducibility for these parameters, the measurements were repeated in 20 patients at 1 week after the initial assessment by the same radiologist as well as an independent investigator.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. Descriptive results, including frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations, were measured for all variables. Student t test was used to assess the association between patient gender and pedicle morphometric parameters. This test was used because gender is a binary qualitative variable, and the morphometric variables are normally distributed quantitative variables. The outer pedicle width (OPW) was re-coded into a binary qualitative variable, and the chi-squared test was used to assess the association between OPW and patient gender, since this measure is considered to be the most important when planning TPSF surgery. For statistical significance, a p value of ≤0.05 was used as the cut-off level. Moreover, inter- and intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated in order to assess the reliability of the morphometric measurements that were obtained by our two radiologists in this study [13].

Results

Our sample included 63 (63.6 %) males and 36 (36.4 %) females, with a mean age of 35.5 ± 16.5 years. The mean age for males was 33.1 ± 14.4 years, while the mean age for females was 39.7 ± 19.1 years (p = 0.012). All morphometric findings are shown in Tables 2, 3 and Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Morphometric findings of the subaxial cervical spine of Arab adults (N = 99; 990 pedicles)

| Parameter | All patients | Males | Females | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | (Range) | Mean ± SD | (Range) | Mean ± SD | (Range) | ||

| C3 | |||||||

| OPH (mm) | 6.4 ± 0.9 | (3.6–9.1) | 6.6 ± 0.8 | (3.8–9.1) | 6.2 ± 0.9 | (3.6–7.5) | 0.003 |

| OPW (mm) | 5.1 ± 1.3 | (1.8–7.7) | 5.2 ± 1.2 | (2.4–7.5) | 4.9 ± 1.4 | (1.8–7.7) | 0.057 |

| IPH (mm) | 3.5 ± 1.0 | (1.5–8.0) | 3.6 ± 1.0 | (1.9–8.0) | 3.3 ± 1.0 | (1.5–5.9) | 0.037 |

| IPW (mm) | 2.8 ± 1.1 | (0.6–7.2) | 2.9 ± 1.0 | (0.7–6.0) | 2.6 ± 1.1 | (0.6–7.2) | 0.100 |

| PA (mm) | 32.2 ± 2.4 | (23.2–39.7) | 32.5 ± 2.5 | (26.6–39.7) | 31.6 ± 2.2 | (23.2–37.2) | 0.017 |

| PL (mm) | 18.0 ± 3.3 | (11.2–36.8) | 18.2 ± 3.5 | (11.6–36.8) | 17.6 ± 3.0 | (11.2–28.6) | 0.181 |

| SPD (mm) | 2.6 ± 0.6 | (1.2–4.4) | 2.7 ± 0.6 | (1.2–4.4) | 2.5 ± 0.5 | (1.3–3.7) | 0.027 |

| LPD (mm) | 2.3 ± 0.8 | (0.8–5.3) | 2.4 ± 0.8 | (0.8–4.6) | 2.2 ± 0.9 | (0.9–5.3) | 0.221 |

| PTA (°) | 40.8 ± 3.4 | (27.4–48.3) | 40.8 ± 3.2 | (32.7–48.3) | 40.8 ± 3.8 | (27.4–47.1) | 0.910 |

| IPD (°) | 24.6 ± 1.8 | (12.7–32.1) | 24.8 ± 1.6 | (20.9–32.1) | 24.2 ± 2.1 | (12.7–28.3) | 0.021 |

| C4 | |||||||

| OPH (mm) | 6.5 ± 1.0 | (3.6–9.2) | 6.7 ± 0.9 | (3.7–9.2) | 6.1 ± 1.0 | (3.6–7.8) | <0.001 |

| OPW (mm) | 5.0 ± 1.3 | (2.1–7.9) | 5.0 ± 1.2 | (2.3–7.9) | 4.9 ± 1.4 | (2.1–7.3) | 0.334 |

| IPH (mm) | 3.4 ± 1.0 | (1.6–7.9) | 3.6 ± 1.0 | (1.8–7.9) | 3.1 ± 0.9 | (1.6–5.2) | 0.004 |

| IPW (mm) | 2.7 ± 1.0 | (0.6–6.3) | 2.8 ± 1.0 | (0.7–6.1) | 2.6 ± 1.0 | (0.6–6.3) | 0.118 |

| PA (mm) | 32.3 ± 2.7 | (22.8–41.0) | 32.6 ± 2.6 | (26.9–41.0) | 31.8 ± 2.7 | (22.8–38.2) | 0.035 |

| PL (mm) | 18.0 ± 3.6 | (12.2–35.0) | 18.1 ± 3.6 | (12.2–34.9) | 17.7 ± 3.7 | (12.5–35.0) | 0.462 |

| SPD (mm) | 2.7 ± 0.6 | (1.2–4.4) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | (1.3–4.4) | 2.5 ± 0.5 | (1.2–3.9) | 0.004 |

| LPD (mm) | 2.5 ± 1.0 | (1.2–6.7) | 2.6 ± 1.0 | (1.2–6.7) | 2.4 ± 1.0 | (1.2–5.2) | 0.278 |

| PTA (°) | 40.4 ± 3.8 | (19.5–48.5) | 40.5 ± 4.1 | (19.5–48.5) | 40.1 ± 3.4 | (29.5–46.0) | 0.515 |

| IPD (mm) | 25.1 ± 1.7 | (11.7–30.3) | 25.3 ± 1.5 | (21.2–30.3) | 24.7 ± 2.0 | (11.7–28.7) | 0.025 |

| C5 | |||||||

| OPH (mm) | 6.2 ± 1.0 | (2.8–9.0) | 6.5 ± 0.9 | (2.8–9.0) | 5.8 ± 1.0 | (4.0–7.9) | <0.001 |

| OPW (mm) | 5.1 ± 1.2 | (2.5–7.3) | 5.2 ± 1.2 | (3.1–7.3) | 5.0 ± 1.2 | (2.5–7.3) | 0.191 |

| IPH (mm) | 3.3 ± 1.0 | (1.2–7.5) | 3.4 ± 1.0 | (1.2–7.5) | 3.1 ± 0.9 | (1.4–5.1) | 0.042 |

| IPW (mm) | 2.8 ± 0.9 | (0.9–5.9) | 2.9 ± 1.0 | (1.1–5.9) | 2.7 ± 0.9 | (0.9–5.2) | 0.080 |

| PA (mm) | 33.0 ± 2.9 | (21.2–41.1) | 33.3 ± 2.9 | (22.8–41.1) | 32.4 ± 3.0 | (21.2–38.3) | 0.045 |

| PL (mm) | 18.6 ± 3.6 | (12.5–38.8) | 18.8 ± 3.6 | (12.5–38.8) | 18.1 ± 3.6 | (12.9–33.0) | 0.201 |

| SPD (mm) | 2.6 ± 0.6 | (1.2–5.1) | 2.7 ± 0.7 | (1.2–5.1) | 2.5 ± 0.5 | (1.2–3.3) | 0.005 |

| LPD (mm) | 2.6 ± 1.2 | (0.8–8.5) | 2.7 ± 1.2 | (1.2–8.5) | 2.5 ± 1.1 | (0.8–5.9) | 0.152 |

| PTA (°) | 40.1 ± 4.2 | (17.5–51.8) | 40.2 ± 4.3 | (17.5–51.8) | 39.9 ± 4.1 | (26.3–48.0) | 0.590 |

| IPD (mm) | 25.6 ± 1.9 | (11.2–30.8) | 25.9 ± 1.6 | (21.5–30.8) | 25.0 ± 2.2 | (11.2–29.0) | 0.004 |

| C6 | |||||||

| OPH (mm) | 6.3 ± 1.0 | (3.1–8.4) | 6.5 ± 0.9 | (3.1–8.4) | 5.9 ± 0.9 | (3.6–7.3) | <0.001 |

| OPW (mm) | 5.2 ± 1.1 | (2.9–7.7) | 5.3 ± 1.1 | (2.9–7.7) | 5.0 ± 1.0 | (3.1–7.2) | 0.088 |

| IPH (mm) | 3.3 ± 0.9 | (1.5–6.8) | 3.5 ± 0.9 | (1.6–6.8) | 3.0 ± 0.9 | (1.5–5.4) | <0.001 |

| IPW (mm) | 2.9 ± 0.9 | (1.0–6.1) | 3.0 ± 0.9 | (1.0–6.1) | 2.7 ± 0.8 | (1.1–4.9) | 0.035 |

| PA (mm) | 33.5 ± 2.9 | (22.9–40.2) | 33.9 ± 2.9 | (25.7–40.2) | 32.8 ± 2.9 | (22.9–38.2) | 0.014 |

| PL (mm) | 18.9 ± 3.6 | (12.9–38.1) | 19.1 ± 3.7 | (12.9–38.1) | 18.5 ± 3.4 | (13.3–33.0) | 0.286 |

| SPD (mm) | 2.6 ± 0.7 | (1.2–4.6) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | (1.2–4.6) | 2.4 ± 0.6 | (1.2–4.0) | 0.001 |

| LPD (mm) | 2.8 ± 1.2 | (1.2–8.4) | 2.9 ± 1.2 | (1.2–8.4) | 2.6 ± 1.1 | (1.2–5.2) | 0.145 |

| PTA (°) | 39.2 ± 3.7 | (22.5–47.5) | 39.2 ± 3.8 | (22.5–46.7) | 39.2 ± 3.5 | (27.4–47.5) | 0.868 |

| IPD (mm) | 25.5 ± 1.9 | (11.7–31.1) | 25.8 ± 1.7 | (21.3–31.1) | 25.0 ± 2.2 | (11.7–28.4) | 0.007 |

| C7 | |||||||

| OPH (mm) | 6.6 ± 0.9 | (3.2–9.0) | 6.8 ± 0.8 | (4.5–8.9) | 6.2 ± 0.9 | (3.2–9.0) | <0.001 |

| OPW (mm) | 5.8 ± 1.2 | (3.1–9.0) | 6.0 ± 1.2 | (3.1–9.0) | 5.4 ± 1.0 | (3.7–7.6) | 0.001 |

| IPH (mm) | 3.6 ± 0.9 | (1.6–7.1) | 3.8 ± 0.8 | (2.1–7.1) | 3.3 ± 0.9 | (1.6–6.4) | <0.001 |

| IPW (mm) | 3.4 ± 0.9 | (1.4–6.2) | 3.6 ± 0.9 | (2.1–6.2) | 3.0 ± 0.7 | (1.4–4.8) | <0.001 |

| PA (mm) | 34.0 ± 3.3 | (23.5–43.3) | 34.5 ± 3.4 | (23.5–43.3) | 33.2 ± 3.0 | (23.7–39.4) | 0.012 |

| PL (mm) | 19.1 ± 3.6 | (12.3–41.1) | 19.3 ± 3.7 | (12.3–41.1) | 18.6 ± 3.2 | (13.3–32.0) | 0.155 |

| SPD (mm) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | (1.2–4.7) | 2.9 ± 0.8 | (1.2–4.7) | 2.6 ± 0.5 | (1.7–3.9) | 0.006 |

| LPD (mm) | 2.4 ± 0.9 | (0.9–5.7) | 2.4 ± 0.9 | (0.9–5.4) | 2.3 ± 0.7 | (0.9–4.6) | 0.414 |

| PTA (°) | 38.1 ± 3.5 | (26.4–48.0) | 38.1 ± 3.4 | (27.5–46.2) | 37.9 ± 3.5 | (26.4–48.0) | 0.679 |

| IPD (mm) | 25.1 ± 1.9 | (11.9–30.7) | 25.3 ± 1.6 | (21.7–30.7) | 24.8 ± 2.4 | (11.9–29.1) | 0.083 |

SD standard deviation, OPH outer pedicle height, OPW outer pedicle width, IPH inner pedicle height, IPW inner pedicle width, PA pedicle axis length, PL pedicle length, SPD superior pedicle distance, LPD lateral pedicle distance, PTA pedicle transverse angle, IPD interpedicular distance

Student t test was used to calculate the p value

Table 3.

Outer pedicle width of the subaxial cervical spine pedicles of Arab adults (N = 99; 990 pedicles)

| Outer pedicle width | All patients | Males | Females | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| C3 | 0.032 | ||||||

| <4.5 mm | 69 | 34.8 | 37 | 29.4 | 32 | 44.4 | |

| ≥4.5 mm | 129 | 65.2 | 89 | 70.6 | 40 | 55.6 | |

| C4 | 0.323 | ||||||

| <4.5 mm | 79 | 39.9 | 47 | 37.3 | 32 | 44.4 | |

| ≥4.5 mm | 119 | 60.1 | 79 | 62.7 | 40 | 55.6 | |

| C5 | 0.256 | ||||||

| <4.5 mm | 67 | 33.8 | 39 | 31.0 | 28 | 38.9 | |

| ≥4.5 mm | 131 | 66.2 | 87 | 69.0 | 44 | 61.1 | |

| C6 | 0.004 | ||||||

| <4.5 mm | 51 | 25.8 | 24 | 19.0 | 27 | 37.5 | |

| ≥4.5 mm | 147 | 74.2 | 102 | 81.0 | 45 | 62.5 | |

| C7 | 0.149 | ||||||

| <4.5 mm | 29 | 14.6 | 15 | 11.9 | 14 | 19.4 | |

| ≥4.5 mm | 169 | 85.4 | 111 | 88.1 | 58 | 80.6 | |

Chi-squared test was used to calculate the p value

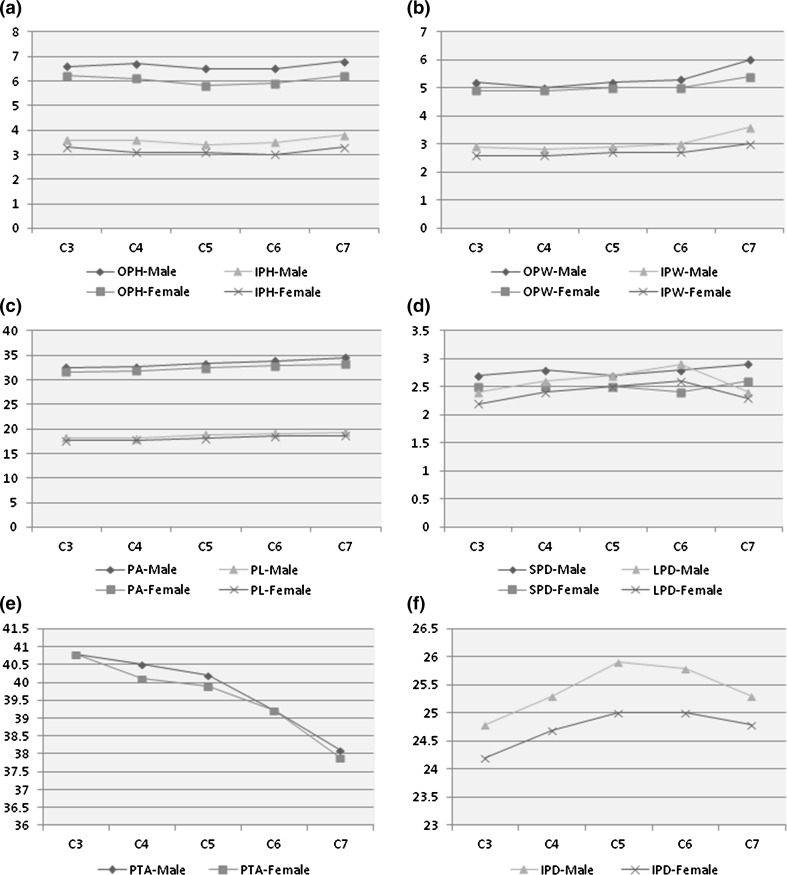

Fig. 2.

Morphometric findings of the subaxial cervical spine among Arab adults (N = 99; 990 pedicles). a Outer pedicle height (OPH) and inner pedicle height (IPH), b outer pedicle width (OPW) and inner pedicle width (IPW), c pedicle axis length (PA) and pedicle length (PL), d superior pedicle distance (SPD) and lateral pedicle distance (LPD), e pedicle transverse angle (PTA), f interpedicular distance (IPD)

Pedicle height and width (Tables 2, 3; Fig. 2a, b)

The mean outer pedicle height (OPH), OPW, inner pedicle height (IPH) and inner pedicle width (IDW) were larger among males at all levels. The most significant differences were observed at C7. A statistically significant difference in OPH and IPH between males and females was noted from C3 to C7 (p values ranged from 0.042 to <0.001). The OPW was significantly larger at C7 only (p = 0.001), while the IPW was significantly larger at C6 (p = 0.035) and C7 (p < 0.001).

A larger percentage of males compared to females had an OPW of ≥4.5 mm at C3–C7 levels (Table 3), which was statistically significant at C3 (p = 0.032) and C6 (p = 0.004). At C4, 79 (39.9 %) of the subjects had an OPW of <4.5 mm. On the other hand, only 29 (14.6 %) subjects had an OPW of <4.5 mm at C7.

Pedicle axis length and pedicle length (Table 2; Fig. 2c)

The mean pedicle axis (PA) length was significantly larger among males at all vertebral levels assessed in this study (p value ranged from 0.045−0.012). The pedicle length (PL) was also larger among males at all levels; however, this difference was not statistically significant. Among all subjects, the smallest PL (11.2 mm) was at C3, while the largest (41.1 mm) was at C7. The overall mean of both PA and PL consistently increased from the cephalad (C3) to the caudad (C7).

Superior and lateral pedicle distances (Table 2; Fig. 2d)

A statistically significant difference was noted in the superior pedicle distance (SPD) between males and females at all C3–C7 levels (p value ranged 0.027–0.001); males also had larger SPD than females. The lateral pedicle distance (LPD) was larger among males; however, this difference was not statistically significant. From C3 to C7, the smallest SPD was 1.2 mm. On the other hand, the smallest LPD (0.8 mm) was seen at both C3 and C5. C5 had the largest SPD (5.1 mm) and LPD (8.5 mm).

Pedicle transverse angle (Table 2; Fig. 2e)

There was no statistically significant difference between males and females in the pedicle transverse angle (PTA). The mean PTA of males and females was equal at C3, and larger among males at all other levels. The largest (51.8°) and smallest (17.5°) PTA was seen at C5. The overall mean of PTA consistently decreased from the cephalad (C3) to the caudad (C7).

Interpedicular distance (Table 2; Fig. 2f)

The mean IPD was larger among males at all vertebral levels. This was statistically significant for all levels except C7 (p values ranged from 0.083−0.004). The smallest IPD was seen in C5, while the largest was at C3.

Reliability

The inter- and intraclass correlation coefficients were between 0.74 and 0.99 for all morphometric parameters. This indicates that reproducibility and repeatability were substantial to almost perfect, respectively.

Discussion

TPSF of the cervical spine was proposed because of the limited biomechanical stability of the commonly used posterior plating techniques. The preferred site of screw placement for posterior plating is the lateral mass [14]. The small amount of bony purchase available in the lateral mass results in biomechanical instability leading to loosening or avulsion of the screw [3]. A significantly higher resistance to pull-out forces, lower rate of loosening and higher strength after fatigue testing were observed with cervical pedicle screws compared to lateral mass screws during biomechanical investigations [3, 15]. In addition, screw-related complications, such as screw loosening, loss of reduction, pseudarthrosis and revision surgery were more commonly reported with lateral mass screws in the subaxial spine [16]. Accordingly, TPSF is being commonly used nowadays.

Although TPSF provides excellent biomechanical stability to the cervical spine, violation of the pedicle cortex is possible. Screw perforation was seen in up to 29.8 % of cases; however, this rarely caused significant complications [16–18]. As a consequence of screw perforation, vertebral artery and nerve root injuries are possible. These complications were reported in a limited number of cases in the literature [16–18]. In order to avoid these serious complications, surgeons should have a proper understanding of the anatomy of the cervical spine and perform appropriate preoperative planning using CT scans for each individual patient. Moreover, the use of intraoperative CT scans, 3-dimensional fluoroscopy and other forms of navigation systems have been shown to reduce the rate of screw perforation and complications [19, 20].

This is the first study to provide CT scan-based morphometric evaluation of the subaxial cervical spine pedicles of Arab adults. Our results revealed that the morphometric parameters of the C3–C7 cervical spine pedicles were larger in males than in females. This finding is similar to results found among other ethnic groups [2, 9, 21, 22]. Spine surgeons should carefully take into account such gender differences before performing TPSF surgery. Moreover, the CT scan dimensions of the subaxial pedicles of our subjects were found to be slightly different when compared to Asians, Europeans and Americans [2, 9]. Height and width were noted to be smaller in Arab people compared to Asians and European/Americans, highlighting the importance of thorough preoperative planning for Arab patients undergoing TPSF of the cervical spine.

The feasibility of inserting a 3.5-mm screw in the pedicle requires a minimum pedicle diameter of 4.5 mm. This diameter allows at least 0.5 mm bony bridge medially and laterally in order to avoid pedicle violation which can result in neurovascular complications [1, 12, 16, 22, 23]. Based on data from previous reports and our current study, the OPW is considered to be the most important parameter in assessing the feasibility of the TPSF technique [1, 2, 9, 12, 24, 25]. This is because the OPH is larger than the width. An OPW of <4.5 mm was seen in more than one-third of males at C4, and more than one-third of females at C3–C6 among our subjects. This indicates that TPSF of the cervical spine is more feasible among Arab males compared to Arab females. Moreover, this technique of fixation appeared to be more applicable at lower cervical vertebral levels in all ethnic groups [2, 9]. The mean OPW of the subaxial spine of Asians ranged from 5.26−6.63 mm, while that of Europeans/Americans ranged from 5.17−6.64 mm [9]. In our current study, this morphometric measurement ranged from 5.0−5.8 mm among Arab people. These results indicate that a preoperative CT scan evaluation is mandatory for Arab patients before TPSF surgery, especially if the patient is female and the fracture involves higher levels of the cervical spine. Another morphometric finding which can help spine surgeons is the PTA, which had a mean of approximately 40° at all C3–C7 levels. This indicates that the angulation of screw placement at the transverse plane should be directed medially in Arab patients to avoid complications. Other studies reported very close values, in which the PTA of the subaxial spine ranged from 37.1° to 49° and 38.7° to 48.8° among Asians and Europeans/Americans, respectively [2, 9]; this means that cervical spine pedicle screw insertion should always be directed medially regardless of the patient’s ethnicity [2, 9, 21, 22].

Although this study provides important information about the morphometry of the subaxial cervical spine pedicles, it has a limitation. Possible differences in the morphometric parameters might exist between Arab people from different geographic regions (i.e., South West Asia vs North Africa). Our study included Arab people from both regions; however, we did not document this feature during our data collection.

In conclusion, the morphometry of the pedicles of the subaxial cervical spine of Arab people shared some similarities and differences compared to other ethnic groups. For the majority of our subjects, inserting screws in the pedicles of C3–C7 vertebrae is feasible. In order to avoid serious intraoperative complications, spine surgeons should carefully assess the morphometry of the pedicles preoperatively for Arab patients undergoing TPSF surgery at the level of the cervical spine.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee. All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Obtaining the informed consent from involved patients was waived by the Research Ethics Committee.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from Kuwait University Research Administration. Grant number is MX01/14.

References

- 1.Ludwig SC, Kramer DL, Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ. Transpedicle screw fixation of the cervical spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;359:77–88. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199902000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chazono M, Tanaka T, Kumagae Y, Sai T, Marumo K. Ethnic differences in pedicle and bony spinal canal dimensions calculated from computed tomography of the cervical spine: a review of the English-language literature. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(8):1451–1458. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2295-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones EL, Heller JG, Silcox DH, Hutton WC. Cervical pedicle screws versus lateral mass screws. Anatomic feasibility and biomechanical comparison. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22(9):977–982. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199705010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaines R. The use of pedicle-screw internal fixation for the operative treatment of spinal disorders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(10):1458–1476. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200010000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu R, Kang A, Ebraheim NA, Yeasting RA. Anatomic relation between the cervical pedicle and the adjacent neural structures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24(5):451–454. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199903010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng CW, Chou BT, Bendo JA, Spivak JM. Vertebral artery injury in cervical spine surgery: anatomical considerations management, and preventive measures. Spine J. 2009;9(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao GP, Zhao JN, Wang YR, Li JS, Chen YX, Wu SJ, Bao NR. Design of cervical pedicle locator and three-dimensional location of cervical pedicle. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(9):1045–1050. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000161011.08086.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosmopopoulos V, Schizas C. Pedicle screw placement accuracy: a metaanalysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32(3):E111–E120. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000254048.79024.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Napolitano JT, Ebraheim NA. Systematic review of cervical pedicle dimensions and projections. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35(24):E1373–E1380. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e92272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebraheim NA, Xu R, Knight T, Yeasting RA. Morphometric evaluation of lower cervical pedicle and its projection. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199701010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan SH, Teo EC, Chua HC. Quantitative three-dimensional anatomy of cervical, thoracic and lumbar vertebrae of Chinese Singaporeans. Eur Spine J. 2004;13(2):137–146. doi: 10.1007/s00586-003-0586-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chazono M, Soshi S, Inoue T, Kida Y, Ushiku C. Anatomical considerations for cervical pedicle screw insertion: the use of multiplanar computerized tomography reconstruction measurements. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4(6):472–477. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.6.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1997;33(1):159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coe JD, Vaccaro AR, Dailey AT, Skolasky RL, Jr, Sasso RC, Ludwig SC, Brodt ED, Dettori JR. Lateral mass screw fixation in the cervical spine: a systematic literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(23):2136–2143. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston TL, Karaikovic EE, Lautenschlager EP, Marcu D. Cervical pedicle screws vs. lateral mass screws: uniplanar fatigue analysis and residual pullout strengths. Spine J. 2006;6(6):667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshihara H, Passias PG, Errico TJ. Screw-related complications in the subaxial cervical spine with the use of lateral mass versus cervical pedicle screws: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19(5):614–623. doi: 10.3171/2013.8.SPINE13136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uehara M, Takahashi J, Ikegami S, Mukaiyama K, Kuraishi S, Shimizu M, Futatsugi T, Ogihara N, Hashidate H, Hirabayashi H, Kato H. Screw perforation features in 129 consecutive patients performed computer-guided cervical pedicle screw insertion. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(10):2189–2195. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yukawa Y, Kato F, Ito K, Horie Y, Hida T, Nakashima H, Machino M. Placement and complications of cervical pedicle screws in 144 cervical trauma patients using pedicle axis view techniques by fluoroscope. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(9):1293–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason A, Paulsen R, Babuska JM, Rajpal S, Burneikiene S, Nelson EL, Villavicencio AT. The accuracy of pedicle screw placement using intraoperative image guidance systems. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20(2):196–203. doi: 10.3171/2013.11.SPINE13413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aoude AA, Fortin M, Figueiredo R, Jarzem P, Ouellet J, Weber MH. Methods to determine pedicle screw placement accuracy in spine surgery: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(5):990–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-3853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta R, Kapoor K, Sharma A, Kochhar S, Garg R. Morphometry of typical cervical vertebrae on dry bones and CT scan and its implications in transpedicular screw placement surgery. Surg Radiol Anat. 2013;35(3):181–189. doi: 10.1007/s00276-012-1013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chanplakorn P, Kraiwattanapong C, Aroonjarattham K, Leelapattana P, Keorochana G, Jaovisidha S, Wajanavisit W. Morphometric evaluation of subaxial cervical spine using multi-detector computerized tomography (MD-CT) scan: the consideration for cervical pedicle screws fixation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panjabi MM, Duranceau J, Goel V, Oxland T, Takata K. Cervical human vertebrae: quantitative three-dimensional anatomy of the middle and lower regions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991;16(8):861–869. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruofu Z, Huilin Y, Xiaoyun H, Xishun H, Tiansi T, Liang C, Xigong L. CT evaluation of cervical pedicle in a Chinese population for surgical application of transpedicular screw placement. Surg Radiol Anat. 2008;30(5):389–396. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onibokun A, Khoo LT, Bistazzoni S, Chen NF, Sassi M. Anatomical considerations for cervical pedicle screw insertion: the use of multiplanar computerized tomography measurements in 122 consecutive clinical cases. Spine J. 2009;9(9):729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]