Abstract

To determine the actual firefighter injury statistics in Korea, we conducted a survey on the nature of on-duty injuries among all male firefighters in Korea. We distributed questionnaires to all Korean male firefighters via email, and data from the 19,119 workers that responded were used for data analysis. The job types were categorized into fire suppression, emergency medical service (EMS) and officers. As estimated of age standardized injury prevalence per one thousand workers, 354 fire extinguishing personnel, 533 EMS workers, and 228 officers experienced one or more injuries during the previous 12 months. The odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of injuries was 1.86 (1.61–2.15) for fire suppression and 2.93 (2.51–3.42) for EMS personnel compared to officers after adjusting for age, marital status, smoking habit and career period. Age standardized absence days from work due to injuries per one thousand workers were 1,120, 1,337, and 676 for fire suppression, EMS and officers, respectively. Car accident (24.5%) was the most common cause and wound (42.3%) was the most common type of injuries. Our nationwide representative study showed that fire suppression and EMS workers are at greater risk of on-duty injuries compared to officers. We observed different injury characteristics compared to those reported in other countries.

Keywords: Injury, Firefighter, Emergency Medical Service, Korea

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The nature of a firefighter’s job is hazardous, and involves rescuing people as well as preventing further escalation of dangerous situations. Hence, the health and well-being of firefighters is key to preserving public safety. However, extinguishing fires and rescuing people, along with the risks inherent in the nature of the job, can threaten firefighters’ health and safety (1). The main hazards include physical, chemical, and psychological stress, which are often unpredictable (2,3). In biomechanics, intrinsic as well as extrinsic energy that surpasses the normal threshold of physiological tolerance can cause injury in affected body regions (4). Firefighters often overexert themselves and are often in unpredictable, extremely dangerous situations, increasing their risk of occupational injuries.

Analysis of injury data from 6 federal agencies in the USA showed that the risk of injury to a firefighter on the job is 2–7 times higher than that of all other industrial workers (5). The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) in the USA (2015) reported 63,350 firefighter injuries in 2014. Among those cases, 27,015 (43%) were fire-ground injuries corresponding to 20.8 injuries per 1,000 fire incidences (6). Falls, slips, and jumps were the most common causes of injuries, followed by over-exertion and strain. Six percent of injuries occurred enroute to or while returning from incident locations.

Generally, the duty of a firefighter can be categorized into extinguishing fires and participating in emergency medical services (EMS, including rescue work). Firefighting and EMS have somewhat different risks for work-related accidents. The injuries that require treatment in hospital emergency departments are almost 2 times higher in career firefighters compared to EMS workers (8.2 vs. 3.0 per 100 workers, respectively) (7). The relative risk (95% confidence interval [CI]) of injuries for fire suppression compared to EMS activities was 2.7 (2.35–3.06) in California compared to 0.6 (0.58–0.73) in New York City (8). Hence, injury characteristics between fire suppression and EMS workers vary widely according to the social system (8). In a study of the rate of compensated occupational injuries among firefighters in Korea, fire suppression caused more on-duty injuries than EMS; the rate of injuries per 100,000 workers was 193.5 in firefighters and 25.4 in EMS personnel (9). However, this study only investigated compensated cases, which did not provide a complete illustration of the nature of injury among firefighters. Furthermore, there has been a lack of investigation on the size and characteristics of injury among firefighters in Korea.

To determine the actual firefighter injury statistics in Korea, we conducted a survey of the nature of on-duty injuries among all firefighters in the country. Our aim was to provide as comprehensive an evaluation as possible to aid in improving safety strategies for firefighters, as well as to improve their health and well-being.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data and study population

Twenty-nine thousand three Korean male firefighters nation-wide received an email containing self-report questionnaires. The response rate was 83.9% (n = 24,348). Among them, we excluded workers aged below 20 and above 60 (n = 137). Workers who had less than 12 months’ experience in the current task job were excluded (n = 5,092). Finally, 19,119 workers were selected for data analysis.

Firefighter definition and occupational injury

For the current study, the term firefighter included all individuals who worked for the fire department as well as related services (10): workers responsible for fire suppression, paramedics, rescue workers, special investigators that determined the cause of fires or disasters, training officers for informatics, and others. Hence, the job was categorized into fire suppression, EMS (including paramedics and rescues) and officers. Officers comprised of individuals that performed administrative work, investigators of fire grounds, and those involved in the communicational and informational system business.

Structured questionnaires were used to identify the experience of job injuries and related absence days from work during the past 12 months. The experiences of injury were limited to only when the event occurred in relation to duties. Furthermore, the occurrence of workplace injuries was defined when the injuries required hospital care: if the injuries did not require hospital care, they were not counted. These criteria were applied to all types of injuries and events including car accidents. The types and number of injuries were measured, and the sites of injury were also reported. The total absence days from work due to injuries during the past 12 months were reported. The total number of experiences with injury as a firefighter was determined with the questionnaires. The length of time in the current job was also measured.

Demographic characteristics

Self-reported structured questionnaires were used for data collection. The questionnaires were composed of questions about occupation, demographic, life style, accidents and injury on duties during the past 12 months (Table 1).

Table 1. Basic characteristic of firefighters.

| Parameters | Not injured | Injured | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | 16,889 (88.34) | 2,230 (11.66) | |

| Age, yr | |||

| 20-29 | 973 (85.43) | 166 (14.57) | < 0.001 |

| 30-39 | 7,035 (86.44) | 1,104 (13.56) | < 0.001* |

| 40-49 | 6,860 (89.73) | 785 (10.27) | |

| 50 -59 | 2,021 (92.03) | 175 (7.97) | |

| Marriage status | |||

| Married | 14,557 (88.66) | 1,862 (11.34) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 2,332 (86.37) | 368 (13.63) | |

| Smoking | |||

| Current smoker | 6,214 (88.64) | 796 (11.36) | < 0.001 |

| Non-smoker | 8,562 (88.65) | 1,096 (11.35) | |

| Former-smoker | 1,259 (84.95) | 223 (15.05) | |

| Alcohol drinking | |||

| Non-heavy alcohol consumption | 15,054 (88.39) | 1,977 (11.61) | 0.494 |

| Heavy alcohol consumption | 1,835 (87.88) | 253 (12.12) | |

| Exercise | |||

| ≥ 3 times a wk | 7,214 (88.13) | 972 (11.87) | 0.434 |

| < 3 times a wk | 9,675 (88.49) | 1,258 (11.51) | |

| Education | |||

| Below high school | 387 (90.21) | 42 (9.79) | 0.432 |

| High school | 6,542 (88.42) | 857 (11.58) | |

| University of above | 9,960 (88.21) | 1,331 (11.79) | |

| Current job | |||

| Fire suppression | 9,004 (88.91) | 1,123 (11.09) | < 0.001 |

| Medical emergency service | 4,001 (82.49) | 849 (17.51) | |

| Officer | 3,884 (93.77) | 258 (6.23) | |

| Experiences as firefighter, yr | |||

| < 5 | 3,096 (85.64) | 519 (14.36) | < 0.001 |

| 5-10 | 2,524 (87.52) | 360 (12.48) | < 0.001* |

| 10-15 | 4,819 (87.76) | 672 (12.24) | |

| 15-20 | 4,031 (89.56) | 470 (10.44) | |

| ≥ 20 | 2,419 (92.05) | 209 (7.95) | |

| Current job experiences, yr | |||

| < 5 | 7,458 (88.75) | 945 (11.25) | < 0.0001 |

| 5-10 | 3,105 (87.42) | 447 (12.58) | 0.393* |

| 10-15 | 3,347 (87.03) | 499 (12.97) | |

| 15-20 | 2,024 (88.81) | 255 (11.19) | |

| ≥ 20 | 955 (91.92) | 84 (8.08) |

*P values for trend which calculated by Cochran-Armitage trend test.

Smoking history was categorized into never smoker, ex-smoker and current smoker. Regular physical activity was defined as more than 20 minutes of physical activity sufficient to cause sweating, 3 or more times per week. Heavy alcohol consumption was defined as drinking 7 or more glasses of alcohol on 2 or more occasions per a week in men (about alcohol 100 mg). Educational levels were categorized into below high school (less than 12 years), high school (12 years), and university or above (over 12 years).

Statistical methods

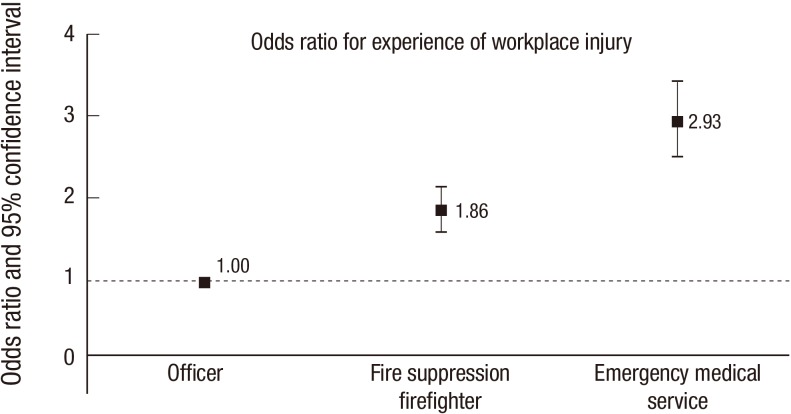

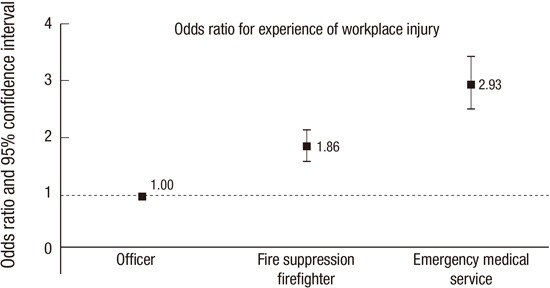

The prevalence of workplace injuries is described in Table 2. We used age adjusted direct standardization methods to calculate the prevalence of injury and the number of injury cases. The prevalence was calculated according to the current job. The absence days from work due to accidents were also age adjusted by direct standardization methods. The direct standardized prevalence was calculated by the age-specific prevalence from each job category. Afterward, the obtained prevalence was multiplied with the reference population for each age group. The age distribution for all firefighters was used as the reference population. The standardized value was multiplied by 1,000 to represent the prevalence or number per one thousand workers during the past 12 months. 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of prevalence were calculated using the mid-p test because certain age groups experienced less than 30 injury cases and we assumed the Poisson’s distribution for the occurrence of injuries in the target population (11). The P values and P values for trend were calculated with the χ2 test and the Cochran-Armitage trend test, respectively. We used a multiple logistic regression model to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals for each injury parameters with officers as the reference group. Age, marital status, smoking habit and career periods were used as confounding variables in the multiple logistic regression model, because those variables show significant differences according to the presence or absence of injury experiences (Fig. 1). All P values below 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Table 2. Age standardized prevalence of workplace injury during past 12 months per 1,000 firefighters.

| Workplace | Total No. of workers | No. of workers who suffer from injuries | No. of injuries | Absence days of work due to injuries | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Age-standardized | Observed | Age-standardized | Observed | Age-standardized | ||

| Fire suppression | 10,127 | 1,216 | 113 (110-114) | 3,516 | 354 (348-358) | 11,667 | 1,120 (1,102-1,133) |

| Emergency medical service | 4,850 | 587 | 168 (164-169) | 1,956 | 533 (524-539) | 3,370 | 1,337 (1,316-1,354) |

| Officer | 4,142 | 299 | 65 (63-66) | 854 | 228 (224-230) | 2,270 | 676 (665-684) |

| Total | 19,119 | 2,102 | 116 (114-117) | 6,326 | 372 (368-374) | 17,307 | 1,044 (1,034-1,052) |

Direct method was used to calculate age standardized ratio, and total firefighter was used for reference population.

Number, ratio (95% confidence interval)

Fig. 1.

Odds ratio of suffering one or more accident during past 12 months according to job categories. Age, marital status, career period, smoking status were controlled by multiple logistic regression model.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted with the approval of the institutional review board (IRB) of Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital (2014-82). The authors obtained written informed consent for participation in the study.

RESULTS

The basic characteristics and risks of injuries among firefighters

The basic characteristics of firefighters according to the experience of injuries on duty are shown in Table 1. Two thousand two hundred thirty (11.66%) firefighters experienced injuries during the past 12 months. Younger firefighters were more likely to experience injuries compared to older workers (14.6% in 20-29 age group and 8.0% in 50-59 age group, P < 0.001 and P for trend < 0.001). Married workers had fewer experiences with injury compared to the others (11.34% vs. 13.63%, respectively, P value < 0.001). Former smokers had higher injury experience compared to non-smokers (15.1% vs. 11.4%, respectively, P < 0.001). The other lifestyle variables such as alcohol drinking, exercise, and education did not influence the injury experience in firefighters.

In terms of current job categories, EMS (17.5%) showed the highest injury experiences among firefighters, followed by fire suppression (11.1%): the prevalence was much higher than that of officers (6.2%, P < 0.001). Shorter experience duration as a firefighter was related to injury experiences (P for trend < 0.001), but shorter current job experience duration was not (P for trend = 0.3928).

The injury prevalence according to the job

One thousand two hundred sixteen among 10,127 fire suppression workers, 587 among 3,169 EMS and 299 among 1,681 officers experienced one or more injuries during the past 12 months. The age standardized prevalence (95% CI) was 113 (110-114), 168 (164-169) and 65 (63-66) per one thousand workers, respectively (Table 2). There were 3,516, 1,956 and 854 accidents among fire suppression, EMS and officers, respectively. The corresponding age standardized prevalence (95% CI) per one thousand workers was 354 (348-358), 533 (524-539) and 228 (224-230). The observed and age standardized absence days of work due to injuries per one thousand workers were 11,667 and 1,120 (1,102-1,133), 3,370 and 1,337 (1,316-1,354), and 2,270 and 676 (665-684) in fire suppression, EMS and officers, respectively. The odds of suffering one or more injuries during the past 12 months were almost 3 times higher in EMS compared to officer workers. Actually, the OR (95% CI) was 1.86 (1.61-2.15) in fire suppression and 2.93 (2.51-3.42) in EMS compared to officers after adjustments for age, marital status, smoking habit and career period as a firefighter (Fig. 1). The OR (95% CI) of injury for EMS was 1.58 (1.42-1.75) compared to that for fire suppression workers (data not shown in Fig. 1).

Causes and types of injuries

The most common cause of injuries in all firefighters was traffic accidents (20.6%, 28.7% and 18.4% of injury cases in fire suppression, EMS and officers, respectively) (Table 3). Slip was the 2nd most common cause of injuries in EMS and officers while chemical intoxication (including lack of oxygen) was the 2nd most common in fire suppression. Explosion was the 3rd most common cause of injuries in all firefighters. Slip during fire suppression, falling down in EMS and chemical intoxication in officers were the 4th most common cause of injuries. Falling down for fire suppression and officers and falling material for EMS were the 5th most common cause of injuries.

Table 3. Causes of injuries in firefighters during past 12 months.

| Causes of injuries | Total firefighters (n = 19,119) | Fire suppression (n = 10,127) | Emergency medical service (n = 4,850) | Officer (n = 4,142) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.* | %† | %‡ | No.* | %† | %‡ | No.* | %† | %‡ | No.* | %† | %‡ | |

| Fall, jump, slip | 883 | 17.8 | 4.6 | 488 | 17.7 | 4.8 | 292 | 17.9 | 6.0 | 103 | 18.1 | 2.5 |

| Overexertion, strain | 280 | 5.6 | 1.5 | 135 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 107 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 38 | 6.7 | 0.9 |

| Contact with object | 519 | 10.5 | 2.7 | 316 | 11.5 | 3.1 | 145 | 8.9 | 3.0 | 58 | 10.2 | 1.4 |

| Struck by an object | 145 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 98 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 31 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 16 | 2.8 | 0.4 |

| Extreme weather | 98 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 53 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 33 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 12 | 2.1 | 0.3 |

| Exposure to fire products | 917 | 18.5 | 4.8 | 524 | 19.0 | 5.2 | 278 | 17.0 | 5.7 | 115 | 20.2 | 2.8 |

| Exposure to chemical or radiation | 515 | 10.4 | 2.7 | 351 | 12.7 | 3.5 | 105 | 6.4 | 2.2 | 59 | 10.4 | 1.4 |

| Car accident | 1,213 | 24.5 | 6.3 | 608 | 22.1 | 6.0 | 495 | 30.3 | 10.2 | 110 | 19.3 | 2.7 |

| Others | 388 | 7.8 | 2.0 | 182 | 6.6 | 1.8 | 148 | 9.1 | 3.1 | 58 | 10.2 | 1.4 |

| Total | 4,958 | 100.0 | 25.9 | 2,755 | 100.0 | 27.2 | 1,634 | 100.0 | 33.7 | 569 | 100.0 | 13.7 |

*All natures of multiple causes were counted for number and percent of prevalence; †proportion of injuries; ‡proportion of workers.

In terms of injury types, cutting/stabbing/piercing wounds were the most common types of injuries among all firefighter job categories (Table 4). Sprain/dislocation/ligament injuries and internal organ injuries were the 2nd and 3rd most common types of injuries, respectively.

Table 4. Types of injuries in firefighters during past 12 months.

| Types of injuries | Total firefighters (n = 19,119) | Fire suppression (n = 10,127) | Emergency medical service (n = 4,850) | Officer (n = 4,142) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.* | %† | %‡ | No.* | %† | %‡ | No.* | %† | %‡ | No.* | %† | %‡ | |

| Fracture | 368 | 9.0 | 1.9 | 215 | 9.9 | 2.1 | 106 | 7.4 | 2.2 | 47 | 9.9 | 1.1 |

| Wound, cut, bleeding, bruise | 1,728 | 42.3 | 9.0 | 904 | 41.6 | 8.9 | 646 | 44.9 | 13.3 | 178 | 37.5 | 4.3 |

| Strain, sprain, muscular pain | 876 | 21.4 | 4.6 | 464 | 21.4 | 4.6 | 306 | 21.3 | 6.3 | 106 | 22.3 | 2.6 |

| Burns (heat or chemical) | 77 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 50 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 19 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 8 | 1.7 | 0.2 |

| Internal organ damage (heat attack, smoke or gas inhalation, other respiratory distress etc.) | 616 | 15.1 | 3.2 | 347 | 16.0 | 3.4 | 198 | 13.8 | 4.1 | 71 | 14.9 | 1.7 |

| Others | 422 | 10.3 | 2.2 | 193 | 8.9 | 1.9 | 164 | 11.4 | 3.4 | 65 | 13.7 | 1.6 |

| Total | 4,087 | 100.0 | 21.4 | 2,173 | 100.0 | 21.5 | 1,439 | 29.7 | 29.7 | 475 | 100.0 | 11.5 |

*All natures of multiple injuries were counted for number and percent of prevalence; †proportion of injuries; ‡proportion of workers.

DISCUSSION

Our analyses of nationally representative data show that there were 116 injured workers and 372 cases of injuries per 1,000 firefighters that required clinical care during the past 12 months. The number of absence days from work due to injuries per 1,000 firefighters was 1,044 days. Roughly, an injury case needs 2.8 days of absence. The EMS and fire suppression workers have much more experience with injuries on duty compared to officer workers, and their odds of injuries were three and two times higher, respectively. Traffic accident is the most common cause of injuries and wound, cut, bleeding and bruising are the most common types of injuries across all job categories.

A study from Poland consisted of a survey with a nationally representative sample of 1,503 firefighters over a 3 years period. There were 352 injuries with 301 victims, responsible for 14,675 days of work absence (12), but the criteria for the injuries were not defined. The annual injury rate and days of absence were 70.3 and 2,937 days per 1,000 workers (12). One injury required approximately 40 or more absence days in the study. In our current study, the annual injury rate and days of absence were 372 and 1,044 days per 1,000 workers, which means less than 3 days of absence were needed for one injury. Because of the lack of definition for injuries, it is impossible to determine the factors responsible for the differences in the results. A survey using questionnaires was conducted with 462 Missouri Valley region firefighters. The definitive criteria for injury on duty included all cases for which an accident report was completed, the workers compensation program was invoked, or medical care was required (13). In the study, 115 firefighters experienced injuries on duty during the past 12 months. Roughly, 25% of all firefighter suffered from injuries. This is similar to a previous report by the US department of Commerce in 2004 (10). The researchers used all on-duty injuries during fire suppression, providing emergency medical service and rescue, and other services for preventing and investigating disasters. The injury rates per 1,000 firefighters were from 22.4 to 25.2 between 2000 and 2002. A retrospective study of Australian firefighters showed that 117 victims per 1,000 workers annually suffered from injuries on duty (14): the injuries were defined as cases when the worker reported the injury to their supervisor. The injury rate for our current analysis (11.6%) was much higher than the Poland report (7%), was similar to the Australian (11.7%) report, but was much lower than the Missouri Valley region and USA (22%-25%) report. Different criteria for injuries on duty might be one of the reasons for such differences. The injury criteria in the Missouri Valley region and USA report was similar to our current study, in that any injuries that needed hospital care were defined as injuries on duty. Hence, the reporting criteria for the Missouri Valley region and USA report, which included all injuries for which an accident report was completed, might be one of the reasons why they reported somewhat higher prevalence of injuries than our current study. Our analysis did not include cases of minor injury that did not need hospital care.

The individuals involved in fire suppression extinguish fires. EMS workers provide urgent care and transfer patients to the hospital system such as emergency departments at hospitals. They usually use ambulances not only for transfer but also to provide suitable care during transportation. The Missouri Valley region report showed that 33% of fire suppression, 21% of EMS, 17% of drivers, and 22% of officers suffered from injuries during the past 12 months (13). A retrospective analysis (8) showed that the rate of injury per 1,000 workers was 186 for fire suppression and 346 for EMS workers. The retrospective analysis showed large differences in the injury rate for fire suppression workers according to the region. The injury rates per 1,000 fire workers were 89 for Maine, 142 for California, 170 For New Jersey and 343 for New York (8). In contrast, EMS showed 1.6 times higher odds of injury compared to fire suppression in the current study: 168 vs. 113 per 1,000 workers, respectively, with an OR of 1.58. Although the definitions of injury may be different in each study, our current study shows differences in injury risk according to job characteristics. The absence days from work due to injuries showed fewer differences between EMS and fire suppression workers, as presented in Table 4. This suggests that the injury might be more severe in fire suppression compared to EMS. Hence, if we used somewhat different criteria for injury that reflect severity, our current results might be different.

A retrospective study of Australian firefighters using the registry database (14) reported that sprains represented almost 70% of all types of injuries. NFPA in the USA analyzed the registry data and reported that the most common type of injuries were strains, sprains and muscular pain (55%) followed by cuts, lacerations and bruises (15%) (6). The Missouri Valley region of the USA report showed that 76.3% of injuries were dislocations, strains and sprains while 13.0% was superficial injuries and open wounds in firefighters (13). A retrospective analysis (8) showed that 55% of total injuries were strains, sprains and tears. To summarize the previous studies, the findings suggested that strains, sprains and muscular pain were the most common types of injuries among firefighters. However, we observed somewhat different results for the common types of injuries. In the current study, wounds, cuts, bleeding, and bruises were the most common types of injuries followed by fractures. This might be due to our definition of injuries, which was all injuries on duty that needed hospital care, whereas other studies used registry data. Generally, registry data have somewhat strict criteria and involve reporting to supervisors or a claim system.

In terms of causes of injuries, falls, jumps and slips accounted for 29% of all injuries, while overexertion and strain accounted for 25% in the 2014 NFPA report. The report did not include the number of car accidents because the NFPA focused only on fire ground injuries. In the current study, commuting car accidents for firefighters was not included under workplace injuries, but car accidents were the most common cause of injuries, accounting for 25% of all cases. With car accidents excluded, falls, jumps and slips were the most common causes of injuries, similar to the USA. The next most common cause of injuries was exposure to fires. Contrary to reports from other centuries, overexertion and strain did not account for a large number of injuries in the current study. This correlated with the observation that strains, sprains and muscular pain were not the most common types of injuries in the current study. We investigated the prevalence of back pain among firefighters (data not shown in current results), and almost 50% of firefighters reported experiencing back pain. These injuries fell under the category of overexertion, strains, sprains and muscular pain that did not need urgent hospital care in the current study.

Recently, some studies reported that noise exposure can aggravate the risk of occupational injury, and the association was related to the degree of exposure (15,16). This may be because noise blocks communication with co-workers and masks warning signals at the fire ground (15,16). If workers have hearing defects, the risk of occupational injury may be increased (17). High frequency noise can be caused by sirens while driving emergency cars or fire trucks, when handling various equipment such as water pumps and saws or with sudden explosions at the fire ground (18). Hence, to prevent occupational injuries for firefighters, plans and programs for noise exposure and hearing defects are needed.

A study from the USA using the Workers Compensation database reported that overall injury rates for females were lower than those for males (19). The trend was significant in all major industries, but was not observed in the service and agriculture sectors. In terms of injury types, carpal tunnel syndrome as well as burns, sprains and fractures are more common types of injuries in females compared to males. Some articles show that the reporting and claim rate for occupational injuries was higher in females compared to males (20). There is a possibility that the occurrence and types of injuries in firefighters might be different according to gender. Because our current investigation only used male firefighters, careful considerations are needed to generalize our results to female firefighters.

Younger firefighters were found to be at greater risk of injuries in the current study, indicating that low job experience increases the risk of injuries. In contrast, a study involving university employees showed that older populations had a higher risk of injuries compared to younger populations (20). Universities might have different demographic characteristics of employees to firefighters, such as age and gender, as well as heterogenic job differences (professor, student and service workers). However, the study did not include stratification analysis for gender, job and other factors. A different study involved a comprehensive investigation of the risk of injuries and other job factors (21). Short or temporary employment periods are related to a lack of knowledge about hazards, consequently, less job experience increased the risk of occupational injuries (21). Our current results of higher risk in younger firefighters suggest that detailed education programs are needed for younger or beginner firefighters to reduce occupational injuries.

A one year follow up prospective study demonstrated that individual factors such as obesity (body mass index and body fat amount), smoking habits, aerobic power and body flexibility were closely related to occupational injury (22). A cross sectional and prospective study using almost two thousand interview respondents did not show a relationship between heavy alcohol drinking and occupational injuries, although there was evidence that alcohol-induced reduction in motor and decision functions are risk factors of occupational injuries (23). However, the study lacked data about life threatening injuries compared to minor injuries because of the nature of the interview study design. Smoking habit was related to occupational injuries in a prospective study using 2,537 postal employees (24). In the current study, we did not find a significant association between occupational injuries and individual characteristics for smoking (non-smoker vs. current smoker), alcohol drinking, and regular exercise. The homogeneity of the participants, as we only used male firefighters, might be the reason for this result.

Our current nationally representative study showed the amounts, types and causes of injuries in firefighters. However, we should consider the limitations to understand and generalize our results. First of all, we used self-reported questionnaires to measure the amounts, types and causes of injuries. Furthermore, our injury criteria included all kinds of injuries on duty that needed hospital care and occurred in relation to the job. Actually, car accidents were included in the current study as injuries on duty if the car usage was related to the job. However, some previous reports focused only on fire ground injuries and used registry data such as workers’ compensation or formalized report systems. Hence, direct comparison without understanding our limitations can lead to serious errors in generalization. Second, self-reported methods involve a certain amount of recall bias. Third, the number as well as severity of fire accidents or disasters in the past 12 months was not adjusted to calculate the amount of injuries. Generally, the number or severity of fire accidents, fire resistance or disasters affect the risk of injuries among firefighters (25). Fourth, as we discussed above, different survey methods and injury criteria should be carefully considered before generalizing or comparing our results to other populations.

In summary, our nationally representative analyses show the amount, types and causes of injuries among firefighters. Among firefighters, fire suppression and EMS workers experienced almost 2 and 3 times more injuries on duty compared to officers. We observed different characteristics of injuries compared to previous reports from other countries and the differences were due to differences in study design. The use of nationally representative data for Korean male firefighters is the main strength of our current study. Therefore, we hope our report can help in the development of preventive strategies for firefighters’ safety and health.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was supported by the Fire Fighting Safety and 119 Rescue Technology Research and Development Program funded by the Ministry of Public Safety and Security (NEMA-Chaseidae-2014-44).

DISCLOSURE: All the authors have approved the manuscript and have agreed to submit it to your esteemed journal. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Conception and design: Yoon JH, Kim KS, Ahn YS. Acquisition of data: Kim KS, Ahn YS. Analysis and interpretation of data: Yoon JH, Kim YK. Writing manuscript: Yoon JH, Kim YK. Revision and approval of final manuscript: all authors.

References

- 1.Matt SE, Shupp JW, Carter EA, Flanagan KE, Jordan MH. When a hero becomes a patient: firefighter burn injuries in the National Burn Repository. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:147–151. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31823dea3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spadafora R. Firefighter safety and health issues at the World Trade Center site. Am J Ind Med. 2002;42:532–538. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim MG, Kim KS, Ryoo JH, Yoo SW. Relationship between occupational stress and work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Korean male firefighters. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2013;25:9. doi: 10.1186/2052-4374-25-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanzode VV, Maiti J, Ray PK. Occupational injury and accident research: a comprehensive review. Saf Sci. 2012;50:1355–1367. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houser AN, Jackson BA, Bartis JT, Peterson DJ. Emergency Responder Injuries and Fatalities: an Analysis of Surveillance Data. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Science and Technology; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haynes HJ, Molis JL. US Firefighter Injuries in 2014. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichard AA, Jackson LL. Occupational injuries among emergency responders. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53:1–11. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguire BJ, Hunting KL, Guidotti TL, Smith GS. Occupational injuries among emergency medical services personnel. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9:405–411. doi: 10.1080/10903120500255065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn Y, Hyun S, Jeong K, Kim K, Choi K, Chae J. The Analysis of Risk Factors Related Health and Safety at Disasters and Development of Special Medical Health Examination System for Firefighters. Seoul: Korea National Emergency Management Agency; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Standards and Technology (US) The Economic Consequences of Firefighter Injuries and Their Prevention. Final Report. Arlington, VA: National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen GR, Yang SY. Mid-P confidence intervals for the Poisson expectation. Stat Med. 1994;13:2189–2203. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780132102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szubert Z, Sobala W. Work-related injuries among firefighters: sites and circumstances of their occurrence. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2002;15:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahnke SA, Poston WS, Haddock CK, Jitnarin N. Injury among a population based sample of career firefighters in the central USA. Inj Prev. 2013;19:393–398. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor NA, Dodd MJ, Taylor EA, Donohoe AM. A retrospective evaluation of injuries to Australian urban firefighters (2003 to 2012): injury types, locations, and causal mechanisms. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57:757–764. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantley LF, Galusha D, Cullen MR, Dixon-Ernst C, Rabinowitz PM, Neitzel RL. Association between ambient noise exposure, hearing acuity, and risk of acute occupational injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2015;41:75–83. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon JH, Hong JS, Roh J, Kim CN, Won JU. Dose - response relationship between noise exposure and the risk of occupational injury. Noise Health. 2015;17:43–47. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.149578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantley LF, Galusha D, Cullen MR, Dixon-Ernst C, Tessier-Sherman B, Slade MD, Rabinowitz PM, Neitzel RL. Does tinnitus, hearing asymmetry, or hearing loss predispose to occupational injury risk? Int J Audiol. 2015;54(Suppl 1):S30–6. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2014.981305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong O, Samo D, Hulea R, Eakin B. Perception and attitudes of firefighters on noise exposure and hearing loss. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2008;5:210–215. doi: 10.1080/15459620701880659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Islam SS, Velilla AM, Doyle EJ, Ducatman AM. Gender differences in work-related injury/illness: analysis of workers compensation claims. Am J Ind Med. 2001;39:84–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-0274(200101)39:1<84::aid-ajim8>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saleh SS, Fuortes L, Vaughn T, Bauer EP. Epidemiology of occupational injuries and illnesses in a university population: a focus on age and gender differences. Am J Ind Med. 2001;39:581–586. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benavides FG, Benach J, Muntaner C, Delclos GL, Catot N, Amable M. Associations between temporary employment and occupational injury: what are the mechanisms? Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:416–421. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.022301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig BN, Congleton JJ, Kerk CJ, Amendola AA, Gaines WG. Personal and non-occupational risk factors and occupational injury/illness. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49:249–260. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veazie MA, Smith GS. Heavy drinking, alcohol dependence, and injuries at work among young workers in the United States labor force. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1811–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan J, Zwerling C, Orav EJ. Occupational risks associated with cigarette smoking: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:29–32. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Britton C, Lynch CF, Torner J, Peek-Asa C. Fire characteristics associated with firefighter injury on large federal wildland fires. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]