In this pooled analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer patients, mutations in KRAS, and BRAF were associated with inferior progression-free and overall survival compared with patients with non-mutated tumors. KRAS exon 2 mutation variants were associated with heterogeneous outcome compared with unmutated tumors with KRAS G12C and G13D being associated with rather poor survival.

Keywords: BRAF, colorectal cancer, mutation, prognostic factor, RAS

Abstract

Background

To explore the impact of KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutations as well as KRAS mutation variants in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) receiving first-line therapy.

Patients and methods

A total of 1239 patients from five randomized trials (FIRE-1, FIRE-3, AIOKRK0207, AIOKRK0604, RO91) were included into the analysis. Outcome was evaluated by the Kaplan–Meier method, log-rank tests and Cox models.

Results

In 664 tumors, no mutation was detected, 462 tumors were diagnosed with KRAS-, 39 patients with NRAS- and 74 patients with BRAF-mutation. Mutations in KRAS were associated with inferior progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) [multivariate hazard ratio (HR) for PFS: 1.20 (1.02–1.42), P = 0.03; multivariate HR for OS: 1.41 (1.17–1.70), P < 0.001]. BRAF mutation was also associated with inferior PFS [multivariate HR: 2.19 (1.59–3.02), P < 0.001] and OS [multivariate HR: 2.99 (2.10–4.25), P < 0.001]. Among specific KRAS mutation variants, the KRAS G12C-variant (n = 28) correlated with inferior OS compared with unmutated tumors [multivariate HR 2.26 (1.25–4.1), P = 0.001]. A similar trend for OS was seen in the KRAS G13D-variant [n = 71, multivariate HR 1.46 (0.96–2.22), P = 0.10]. More frequent KRAS exon 2 variants like G12D [n = 152, multivariate HR 1.17 (0.86–1.6), P = 0.81] and G12V [n = 92, multivariate HR 1.27 (0.87–1.86), P = 0.57] did not have significant impact on OS.

Conclusion

Mutations in KRAS and BRAF were associated with inferior PFS and OS of mCRC patients compared with patients with non-mutated tumors. KRAS exon 2 mutation variants were associated with heterogeneous outcome compared with unmutated tumors with KRAS G12C and G13D (trend) being associated with rather poor survival.

introduction

KRAS exon 2–4 and NRAS exon 2–4 mutations (=RAS mutations) are found in ∼50% of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) tumors and exclude affected patients from epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-directed therapy [1–3]. Besides their negative predictive value, RAS mutations may also carry distinct prognostic information [4–6]. Some studies suggest that EGFR inhibition may even be detrimental in patients with RAS-mutant mCRC [1, 7] maybe due to interaction with the chemotherapeutic backbone [8–10]. Furthermore, low prevalence of the different RAS mutation variants limits conclusions concerning the impact of different subtypes of RAS mutation on prognosis so far.

BRAF V600E mutation occurs in ∼5%–10% of mCRC tumors [1, 5, 11]. Despite the limitation of sample size in single trials, BRAF mutation represents a consistently poor prognostic marker in the context of mCRC treatment [1, 11, 12], associated with rapid clinical deterioration after progression to initial therapy [12]. However, promising data with combination regimens as well as experimental treatment options may lead to routine assessment of this mutation in mCRC in the near future [5, 13].

This analysis was designed to explore the prognostic impact of mutations in RAS genes, their subtypes and BRAF on outcome of mCRC patients treated within randomized trials of the AIO colorectal cancer study group. With respect to potentially confounding factors of EGFR-based treatment, patients receiving EGFR-targeted agents as first-line therapy were not included.

patients and methods

studies

This analysis is based on individual patient data from five first-line trials in mCRC: FIRE-1 [14, 15], FIRE-3 (only bevacizumab-arm) [2, 16, 17], AIO KRK 0604 [18], AIO KRK 0207 [19] and RO91 [20]. Protocols, responsibilities, declarations of Helsinki, ethical approvals, definitions, treatment schedules and results of the studies were reported previously [2, 14, 18–20].

molecular assessment

Patients were derived from molecularly characterized subsets of the original study-populations (that were evaluated for KRAS exon 2 mutations and BRAF V600E mutation). FIRE-1, FIRE-3 and AIO KRK 0207 were additionally analyzed for mutations in KRAS exon 3–4 as well as NRAS exon 2–4. Methods of testing have been reported in previous publications [15–19, 21]. Patients were only included into the analysis if a single specified (i.e. including base-exchange) RAS/BRAF mutation or no RAS/BRAF mutation was present.

patient data

The following information was assessed for all patients: sex, age, mutation information, treatment, ECOG, location of primary tumor (colon versus rectum), metastatic spread, prior adjuvant chemotherapy, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) and response information.

PFS and OS

PFS was defined as interval between randomization or registration and progression or death from any cause. OS was defined as interval between randomization or registration and death from any cause. For AIO KRK 0207, PFS and OS were calculated from the initial registration (start of induction therapy, and not from randomization for maintenance treatment arms) in order to enable comparison of efficacy parameters [19].

influence of treatment on outcome

The outcome of molecular subgroups was also analyzed in the context of different treatment regimens (oxaliplatin- versus irinotecan-based therapy as well as bevacizumab versus non-bevacizumab therapy). For the assessment of irinotecan- versus oxaliplatin-based treatment, the mIROX arm of the FIRE-1 trial was excluded from the dataset.

statistical analysis

PFS and OS were assessed by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with log-rank tests. Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated by the Cox regression models stratified by study and treatment if appropriate. Multivariate tests were carried out using the Cox models adjusted for study treatment, ECOG, sex, adjuvant chemotherapy, liver-limited disease and number of involved organs. Comparisons of patients with mutation variants to patients with wild-type mCRC were adjusted for multiplicity (Dunnett's test). The significance level was set to 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and R (version 3.2.2).

results

For this analysis, data of 1239 patients were available. Distribution of patients across studies according to molecular characteristics is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients and studies

| Original study (recruiting years) [full population] | Evaluable subset | No mutation, n = 664 (%) | KRAS mutation, n = 462 (%) | NRAS mutation, n = 39 (%) | BRAF mutation, n = 74 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIRE-1 (2000–2004) [n = 479] | FUFIRI (n = 108, 100%) | 45 (41.7) | 55 (50.9) | 7 (6.5) | 1 (0.9) |

| mIROX (n = 100, 100%) | 48 (48) | 41 (41.0) | 4 (4.0) | 7 (7.0) | |

| FIRE-3 (2007–2012) [n = 362] | FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab (n = 283, 100%) | 177 (62.5) | 69 (24.4) | 12 (4.2) | 25 (8.8) |

| AIO KRK 0604 (2005–2006) [n = 255] | CAPOX plus bevacizumab (n = 110, 100%) | 65 (59.0) | 40 (36.4)a | n.a | 5 (4.5) |

| CAPIRI plus bevacizumab (n = 103, 100%) | 72 (70.0) | 30 (29.1)a | n.a. | 1 (1.0) | |

| AIO KRK 0207b (2009–2013) [n = 472] | Observation (n = 115, 100%) | 47 (40.9) | 53 (46.1) | 8 (7.0) | 7 (6.1) |

| bevacizumab (n = 109, 100%) | 45 (41.3) | 53 (48.6) | 4 (3.7) | 7 (6.4) | |

| FP plus bevacizumab (n = 109, 100%) | 48 (44.0) | 49 (45.0) | 4 (3.7) | 8 (7.3) | |

| RO91 (2002–2004) [n = 474] | CAPOX/FUFOX (n = 202) | 117 (57.9) | 72 (35.6)a | n.a. | 13 (6.4) |

n.a., not assessed; FP, fluoropyrimindine; percentages in parentheses indicate percentage of molecular subgroups within the respective study(-arm). FUFIRI, infusional 5-FU, folinic acid, irinotecan; mIROX, irinotecan plus oxaliplatin; FOLFIRI, infusional and bolus 5-FU, folinic acid, irinotecan; CAPOX, capecitabine, oxaliplatin; CAPIRI, capecitabine, irinotecan; FUFOX, infusional 5-FU, oxaliplatin.

aOnly tested for KRAS exon 2 mutations.

bTwenty-four weeks fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin plus bevacizumab.

mutations

Of 1239 analyzed tumors, in 664 tumors (53.6%), no mutation was detected, whereas 462 tumors harboring KRAS (37.3%) mutations and 39 NRAS (3.1%) mutations were found. Additionally, a total of 74 tumors (6.0%) were carrying BRAF V600E mutations (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

baseline characteristics

Distributions of baseline characteristics in molecular subgroups are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics according to molecular subgroups

| No mutation (n = 664) | KRAS mutation (n = 462) | NRAS mutation (n = 39) | BRAF mutation (n = 74) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Median (range) | 65 (25–82) | 64 (25–83) | 64 (32–81) | 62 (29–82) | 0.17 |

| Missing data | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male (%) | 460 (69.3) | 292 (63.2) | 21 (53.8) | 37 (50.7) | 0.002 |

| Female (%) | 204 (30.7) | 170 (36.8) | 18 (46.2) | 36 (49.3) | |

| Missing data | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Primary tumor site | |||||

| Colon (%) | 414 (63.1) | 286 (61.9) | 23 (59.0) | 56 (77.8) | 0.06 |

| Rectum (%) | 236 (36.0) | 175 (37.9) | 15 (38.5) | 15 (20.8) | |

| Colon + rectum (%) | 6 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Missing data | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| ECOG performance status | |||||

| 0 (%) | 340 (51.3) | 225 (49.7) | 18 (46.2) | 33 (45.8) | 0.64 |

| 1 (%) | 297 (44.8) | 206 (45.5) | 20 (51.3) | 33 (45.8) | |

| 2 (%) | 26 (3.9) | 22 (4.9) | 1 (2.6) | 6 (8.3) | |

| Missing data | 1 | 9 | 0 | 2 | |

| Prior adjuvant treatment | |||||

| Adjuvant treatment (%) | 140 (21.1) | 87 (18.9) | 10 (25.6) | 11 (15.1) | 0.43 |

| Missing data | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Metastatic lesions | |||||

| Liver (%) | 550 (83.2) | 366 (80.6) | 33 (84.6) | 57 (78.1) | 0.54 |

| Missing data | 3 | 8 | 0 | 1 | |

| Liver limited (%) | 290 (43.9) | 164 (36.1) | 15 (38.5) | 22 (30.1) | 0.02 |

| Missing data | 3 | 8 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lung (%) | 196 (29.7) | 184 (40.5) | 13 (33.3) | 17 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Missing data | 3 | 8 | 0 | 1 | |

| Peritoneum | 30 (5.5) | 20 (5.2) | 5 (12.8) | 12 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| Missing data | 120 | 80 | 0 | 14 | |

| Lymph nodes | 80 (29.7) | 29 (17.8) | 9 (39.1) | 13 (40.6) | 0.005 |

| Missing data | 395 | 299 | 16 | 42 | |

| >2 organs involved | 99 (15.0) | 77 (17.0) | 11 (28.9) | 15 (20.5) | 0.10 |

| Missing data | 4 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |

P values by χ2 tests, except for age: Wilcoxon's test. Calculations based on non-missing data. Metastastic spread reported to different extent in studies with evaluable data for all trials concerning liver and lung metastases and no of involved organs. Karnofsky performance status was translated into ECOG for the FIRE-1 study: Karnofsky 100 = ECOG 0; Karnofsky 80–90 = ECOG 1; Karnofsky 70 = ECOG 2.

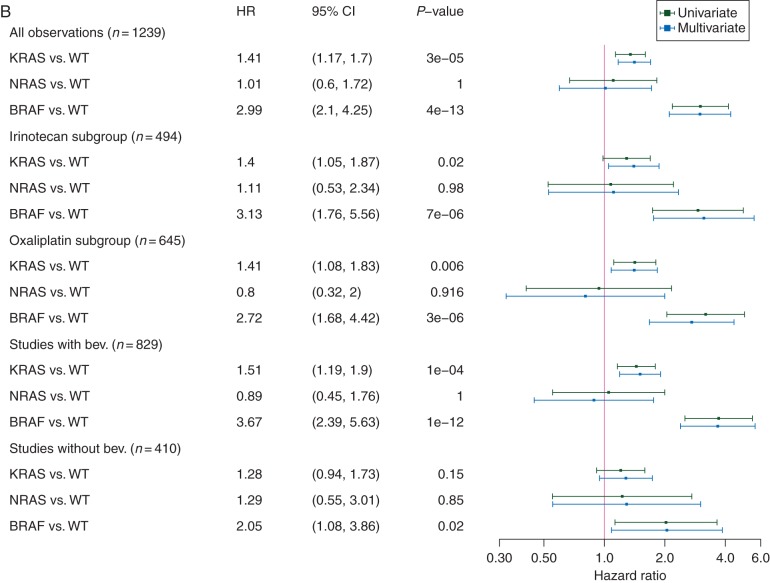

prognostic role of KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutation

PFS and OS were significantly influenced by molecular subgroups (Figures 1A and B and 2A and B). Univariate and multivariate comparisons of PFS and OS in patients with mutant tumors (KRAS, NRAS, BRAF) versus patients with non-mutated tumors revealed a negative prognostic effect of KRAS and BRAF mutations (Figure 2A and B). Interestingly, the negative prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF mutations was consistently observed across different treatment regimens (subgroups of irinotecan- and oxaliplatin-treated as well as in bevacizumab- and non-bevacizumab-treated) (Figure 2A and B).

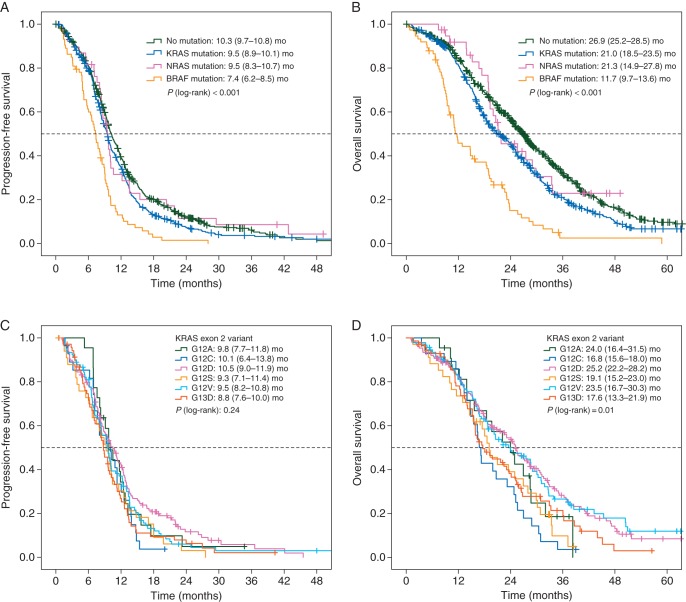

Figure 1.

Prognostic role of alterations in KRAS-, NRAS- and BRAF-genes. (A) Progression-free survival (PFS) according to molecular subgroups. (B) Overall survival (OS) according to molecular subgroups. (C) PFS in KRAS exon 2 variants. (D) OS in KRAS exon 2 variants, P values below 0.05 by log-rank test indicate at least one significant difference between two groups.

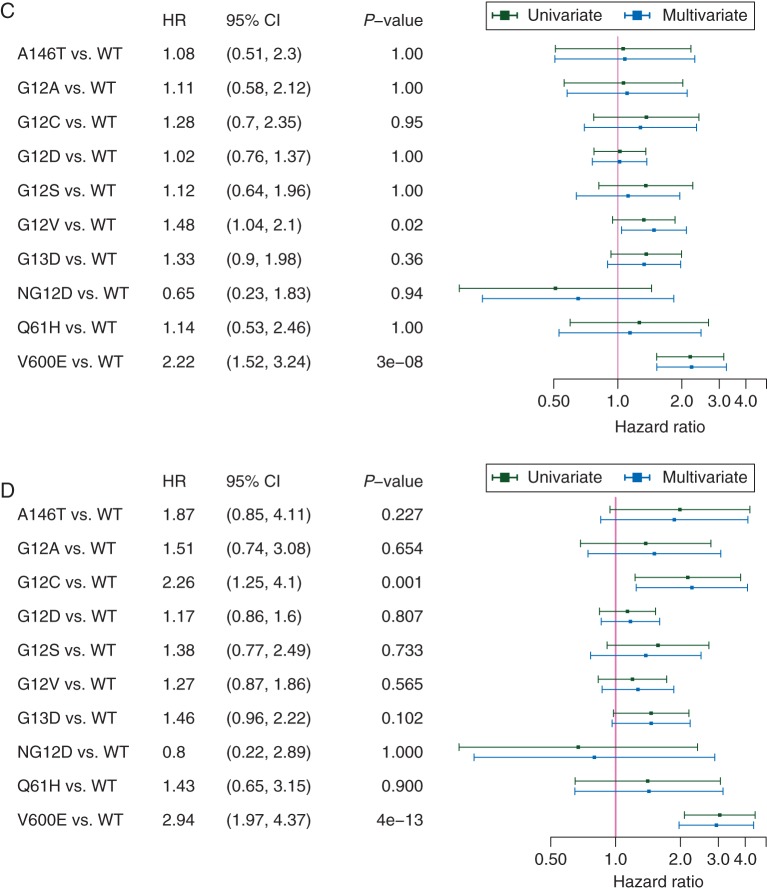

Figure 2.

Forest plots of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) molecular subgroups as well as mutation variants compared with KRAS/NRAS/BRAF wild-type mCRC. (A) Progression-free survival (PFS) according to molecular subgroups. (B) Overall survival (OS) according to molecular subgroups. (C) PFS according to mutation variants. (D) OS according to mutation variants; hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) adjusted for multiplicity indicate results drawn from the multivariate model. An HR >1 indicates a higher hazard rate for death or progression in patients with mutated tumors compared with patients with unmutated tumors. Only mutation variants with >10 patients were included into the analysis in C and D. All variants in C and D represent respective KRAS mutations except NG12D, NRAS G12D; V600E, BRAF V600E; bev., bevacizumab; WT, unmutated tumors.

prognostic role of single RAS mutation variants

The median PFS of patients with KRAS exon 2 mutant tumor subtypes ranged from 8.8 [95% confidence interval (CI) 7.6–10.0] months (G13D mutation) to 10.5 (95% CI 9.0–11.9) months in (G12D variants). The median OS widely ranged between 16.8 (95% CI 15.6–18.0) months (G12C) and 25.2 (95% CI 22.2–28.2) (G12D variants) (Figure 1C and D). Besides KRAS exon 2 variants, KRAS mutations A146T (n = 18) and Q61H (n = 17) as well as NRAS mutation G12D (n = 11) were separately evaluated for efficacy end points, all other variants were less frequent (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Comparisons of PFS and OS (univariate and multivariate) of patients with mutation variants to patients with non-mutated tumors revealed the KRAS exon 2 G12C-variant (n = 28) to correlate with inferior OS compared with non-mutated tumors [multivariate model HR 2.26 (1.25–4.1), P = 0.001] (Figure 2C and D). A similar trend was seen in the KRAS exon 2 G13D-variant [n = 71, multivariate model HR 1.46 (0.96–2.22), P = 0.10]. More frequent KRAS exon 2 variants like G12D [n = 152, multivariate model HR 1.17 (0.86–1.6), P = 0.81] and G12V [n = 92, multivariate model HR 1.27 (0.87–1.86), P = 0.57] did not have significant impact on OS. The G12V mutation variant had a negative prognostic effect on PFS in the multivariate analysis (Figure 2C).

discussion

The present analysis was motivated by the limited clinical data regarding the prognostic impact of RAS mutation variants in patients with mCRC receiving first-line systemic treatment without EGFR-targeted therapy. Our analysis comprises data of 1239 patients and therefore represents one of the largest datasets available.

KRAS (37.3%) and NRAS (3.1%) mutations were a little less frequent in our cohort compared with other series. [1, 22]. Selection of KRAS exon 2 wild-type for inclusion in the FIRE-3 trial as well as lack of testing for KRAS exon 3–4 and NRAS exon 2–4 in AIO KRK 0604 and RO91 may have contributed to this result. The lack of testing in these two studies might cause a small negative bias on outcome of patients with unmutated tumors.

Baseline characteristics compared between molecular subgroups reflected more aggressive disease in patients with mutated tumors (in particular in patients with BRAF-mutant mCRC). BRAF mutation seemed associated with female sex and tumor location (colon). These results confirm previous observations [23].

PFS of patients evaluated by molecular subgroups demonstrated a strong negative prognostic effect of BRAF mutation (HR 2.19, P < 0.0001) as well as a smaller, but also significant negative effect of KRAS mutation, both compared with non-mutated tumors (HR 1.2, P = 0.03). The differences in outcome associated with molecular subtype were pronounced in OS. Of note, the median OS reported in patients with non-mutated tumors was 26.9 (95% CI 25.2–28.5) months. Taking into account that not all patients had access to EGFR-targeted agents since these were partly unavailable at the time of study conduct of FIRE-1/RO91, this result compares well with recent reports of first-line treatment in mCRC [5, 24]. Outcome of patients with KRAS or BRAF-mutant mCRC demonstrated significantly shorter medians of OS: 21.0 (18.5–23.5) and 11.7 (9.7–13.6) months, respectively, translating to HRs of 1.41 (P < 0.001) for KRAS and 2.99 (P < 0.001) for BRAF. Availability of later-line treatment (i.e. EGFR-targeted agents) in patients with non-mutated tumors might have impacted on OS for those patients. However, the also present differences in PFS in patients with non-mutated tumors compared with patients with KRAS-mutant mCRC support the hypothesis that KRAS is a prognostic factor per se and differences in outcome are not only mediated by a subset of patients receiving later-line EGFR-inhibitors. The number of patients with NRAS-mutant tumors in this dataset was probably too small to allow for significant effects on outcome.

In this pooled dataset, the prognostic effect of molecular subgroups (i.e. KRAS and BRAF mutation) in comparison with non-mutated tumors was consistently observed in all subsets of patients being treated with irinotecan- or oxaliplatin combinations as well as in bevacizumab- or non-bevacizumab-treated patient. Considering that microsatellite-instable tumors are rare in stage IV mCRC, these findings compare well with a recent analysis of the adjuvant PETACC-8-trial that identified KRAS and BRAF mutations as prognostic markers in microsatellite-stable (but not microsatellite-instable) tumors [25]. Further classification of mCRC might be seen in differentiation of left-sided versus right-sided primary tumor location, probably being a surrogate for molecular profiles that have not been understood in full extent [26]. Unfortunately, primary tumor location was not recorded during study conduct for the majority of patients in this cohort and cannot be taken into account for our analysis.

KRAS exon 2 mutation variants were associated with heterogeneous outcome concerning OS as well as PFS. The G12V mutation variant, representing one of the most frequent subtypes, was associated with a significantly worse PFS compared with patients without any mutation (HR = 1.48, P = 0.02). OS was also inferior—however not significant—in G12V and G13D 1 subtypes, and significantly inferior in G12C mutations variants compared with patients with non-mutated tumors. This observation supports the hypothesis that KRAS exon 2 mutation variants are associated with a differing spectrum of clinical outcome [4, 8, 27]. It might be speculated that the reason for differing outcomes could be mediated by differing activation of KRAS-depending pathways by distinct mutation variants, as suggested previously with high baseline activation and potentially aggressive biology in G12C variants [28]. In addition, the poor outcome of patients with G12C mutant mCRC might be of clinical relevance as allele-specific inhibitors may provide therapeutic options in the future [29, 30]. In this context, also the mutation rate of KRAS could be a factor that impacts significantly on prognosis of KRAS-mutant mCRC [31]. Unfortunately, this information is not available for our cohort.

In general, despite high data quality, pooled datasets of different randomized trials may always lead to cohorts with study-specific bias. Although multivariate models can adjust calculations for some (obvious) factors, retrospectively evaluated, pooled data invoke uncertainties. Pooling data from five studies has enlarged the number of some mutation variants (i.e. NRAS as well as KRAS exon 2 mutation variants) to a level that consecutively enabled survival analysis. However, absolute numbers in these subgroups are still unsatisfactory and the analyses appear underpowered to allow for definite conclusions, especially in rare mutation variants. In particular, false-negative results cannot be excluded as potential limitations in this setting. Given that some biomarkers (i.e. KRAS mutation variants) were identified as potential prognostic markers, validation of our findings within alternative study-sets appears justified.

In conclusion, our data suggest that mutations in KRAS and BRAF are associated with inferior PFS and OS of mCRC patients compared with patients with non-mutated tumors. Whereas role of chemotherapy and treatment with or without bevacizumab did not affect these findings, KRAS exon 2 mutation variants differed, with G12C being associated with shorter OS when compared with patients with non-mutated tumors, while G13D mutations were showing a similar trend.

funding

FIRE-1 was supported by Pfizer; FIRE-3 was supported by Merck and Pfizer; RO91 and AIOKRK0604 were supported by Roche and Sanofi; AIOKRK0207 was supported by Roche. The present evaluation did not receive specific funding and the funding sources did not contribute to this evaluation.

disclosure

DPM: honoraria: Merck, Roche, Amgen, Bayer; advisory role: Merck, Bayer, Amgen; research grant: Amgen (inst), Merck (inst), Roche (inst); travel support: Amgen, Merck, Sanofi, Bayer.

VH: honoraria: Merck, Roche, Amgen, Sirtex, Sanofi-aventis; advisory role: Merck, Roche, Amgen, Sirtex, Sanofi-aventis; research funding: Amgen, Merck, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis; travel support: Merck, Roche. SS: honoraria: Merck, Roche, Amgen, Bayer, Sanofi-aventis; advisory role: Merck Serono, Roche; travel support: Roche, Merck Serono, Sanofi-aventis. UG: honoraria: Amgen, Roche, Merck, Sanofi, Bayer. DA: honoraria: Bayer, Merck, Roche, Sanofi; advisory role: Roche, Bayer, Merck, Servier, Sandoz ARS: honoraria: Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck, Celgene, Amgen, Roche; advisory role: Amgen, Roche, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck, Celgene; research support: Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Celgene. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and families for participation in the studies, as well as all involved study centers, colleagues and nurses.

references

- 1.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1065–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Cutsem E, Lenz HJ, Kohne CH et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazan V, Migliavacca M, Zanna I et al. Specific codon 13 K-ras mutations are predictive of clinical outcome in colorectal cancer patients, whereas codon 12 K-ras mutations are associated with mucinous histotype. Ann Oncol 2002; 13: 1438–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C et al. FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: updated overall survival and molecular subgroup analyses of the open-label, phase 3 TRIBE study. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 1306–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Hartmann JT et al. Efficacy according to biomarker status of cetuximab plus FOLFOX-4 as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: the OPUS study. Ann Oncol 2011; 22: 1535–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modest DP, Brodowicz T, Stintzing S et al. Impact of the specific mutation in KRAS codon 12 mutated tumors on treatment efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving cetuximab-based first-line therapy: a pooled analysis of three trials. Oncology 2012; 83: 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peeters M, Douillard JY, Van Cutsem E et al. Mutant KRAS codon 12 and 13 alleles in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: assessment as prognostic and predictive biomarkers of response to panitumumab. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 759–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tejpar S, Celik I, Schlichting M et al. Association of KRAS G13D tumor mutations with outcome in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with first-line chemotherapy with or without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 3570–3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Lang I et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2011–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seligmann J. Exploring the poor outcomes of BRAF mutant (BRAF mut) advanced colorectal cancer (aCRC): analysis from 2,530 patients (pts) in randomized clinical trials (RCTs). J Clin Oncol 2015; 33 (Suppl): abstr 3509. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corcoran RB, Atreya CE, Falchook GS et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition with dabrafenib and trametinib in BRAF V600-mutant colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 4023–4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer von Weikersthal L, Schalhorn A, Stauch M et al. Phase III trial of irinotecan plus infusional 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid versus irinotecan plus oxaliplatin as first-line treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2011; 47: 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stahler A, Heinemann V, Giessen-Jung C et al. Influence of mRNA expression of epiregulin and amphiregulin on outcome of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with 5-FU/LV plus irinotecan or irinotecan plus oxaliplatin as first-line treatment (FIRE 1-trial). Int J Cancer 2016; 138: 739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stintzing S, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Decker T et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer-subgroup analysis of patients with KRAS: mutated tumours in the randomised German AIO study KRK-0306. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: 1693–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stintzing S, Jung A, Rossius L, Modest DP et al. Analysis of KRAS/NRAS and BRAF mutations in FIRE-3 A randomized phase III study of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab or bevacizumab as first-line treatment for wild-type KRAS (exon 2) metastatic colorectal cancer patients. In ESMO/ECCO, 2013; Abstract E17-7073. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmiegel W, Reinacher-Schick A, Arnold D et al. Capecitabine/irinotecan or capecitabine/oxaliplatin in combination with bevacizumab is effective and safe as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase II study of the AIO colorectal study group. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 1580–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegewisch-Becker S, Graeven U, Lerchenmuller CA et al. Maintenance strategies after first-line oxaliplatin plus fluoropyrimidine plus bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (AIO 0207): a randomised, non-inferiority, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 1355–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porschen R, Arkenau HT, Kubicka S et al. Phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and leucovorin plus oxaliplatin in metastatic colorectal cancer: a final report of the AIO Colorectal Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 4217–4223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinacher-Schick A, Schulmann K, Modest DP et al. Effect of KRAS codon13 mutations in patients with advanced colorectal cancer (advanced CRC) under oxaliplatin containing chemotherapy. Results from a translational study of the AIO colorectal study group. BMC Cancer 2012; 12: 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumann J, Zeindl-Eberhart E, Kirchner T, Jung A. Frequency and type of KRAS mutations in routine diagnostic analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer. Pathol Res Pract 2009; 205: 858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokota T, Ura T, Shibata N et al. BRAF mutation is a powerful prognostic factor in advanced and recurrent colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2011; 104: 856–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simkens LH, van Tinteren H, May A et al. Maintenance treatment with capecitabine and bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer (CAIRO3): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Lancet 2015; 385: 1843–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taieb J, Zaanan A, Le Malicot K et al. Prognostic effect of BRAF and KRAS mutations in patients with stage iii colon cancer treated with leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin with or without cetuximab: a post hoc analysis of the PETACC-8 trial. JAMA Oncol 2016; 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Missiaglia E, Jacobs B, D'Ario G et al. Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1995–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Roock W, Jonker DJ, Di Nicolantonio F et al. Association of KRAS p.G13D mutation with outcome in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. JAMA 2010; 304: 1812–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camaj P, Primo S, Wang Y et al. KRAS exon 2 mutations influence activity of regorafenib in an SW48-based disease model of colorectal cancer. Future Oncol 2015; 11: 1919–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lito P, Solomon M, Li LS et al. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science 2016; 351: 604–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML et al. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature 2013; 503: 548–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vincenzi B, Cremolini C, Sartore-Bianchi A et al. Prognostic significance of K-Ras mutation rate in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 31604–31612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.