Abstract

Introduction

There is insufficient evidence regarding the appropriate dose of methotrexate (MTX) required to achieve specific treatment goals in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) receiving biologic drugs in Japan. The present study aimed to assess the dose–response effect of MTX in combination with adalimumab (ADA) to achieve low disease activity (LDA) and/or remission at 24 weeks in RA patients.

Methods

This analysis used data of the ADA all-case survey in Japan (n = 7740), and 5494 patients who received ADA and MTX were classified into five groups by weighted average MTX dose (>0–<4, 4–<6, 6–<8, 8–< 10, and ≥10 mg/week). Of the 5494 patients, 3097 with baseline 28-joint disease activity score based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate >3.2 were analyzed for effectiveness by MTX dose.

Results

In biologic-naïve patients (n = 1996/3097), LDA/remission rates increased with MTX up to 6–<8 mg/week and then plateaued at higher doses (LDA, p = 0.0440; remission, p = 0.0422). In biologic-exposed patients (n = 1101/3097), LDA/remission rates increased with MTX dose (LDA, p = 0.0009; remission p = 0.0143). The incidences of serious adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and serious infections did not differ by MTX dose, but total ADRs and infections were significantly higher (p < 0.05) with increased MTX doses.

Conclusion

The appropriate MTX doses in combination with ADA to achieve LDA and/or remission at week 24 were different between biologic-naïve and biologic-exposed patients with RA, suggesting that 8 mg/week of MTX would be enough for biologic-naïve patients.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01076959.

Funding

AbbVie and Eisai Co., Ltd.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40744-015-0023-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adalimumab, Doses, Effectiveness, Methotrexate, Rheumatoid arthritis, Safety

Introduction

Adalimumab (ADA; Humira®, AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL, USA), a fully human monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-α, was approved in Japan in 2008 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1–4]. The safety and effectiveness of ADA has been confirmed with the results of an all-case postmarketing surveillance study that enrolled 7740 Japanese patients with RA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01076959) [5, 6]. Methotrexate (MTX) was approved in Japan in 1999 for the treatment of RA at the dose of ≤8 mg/week, and higher doses up to 16 mg/week, which is lower than the maximum weekly dose in Western countries, were additionally approved in 2011 [7]. Clinical studies conducted in and outside of Japan have shown that the combination of ADA and MTX is more effective than monotherapy with either drug [8–12]. In fact, the 2013 updates of the EULAR recommendations for the management of RA with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs describe that biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) should be used preferentially in combination with MTX or other conventional synthetic DMARDs [8]. However, evidence is lacking in terms of the optimal dose of MTX used in combination with TNF inhibitors. While the CONCERTO trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01185301) [11] has described the dose–response profile of MTX in bio-naïve patients with early stage RA, no studies have reported the corresponding data in patients with established RA in the clinical setting. In the present (MELODY) study, we conducted an analysis of data from the all-case postmarketing surveillance of ADA in 7740 Japanese patients with RA [6] by stratifying patients according to the clinical MTX dosages used in order to evaluate the effects of MTX dose in patients receiving ADA. Patients were classified as biologic-naïve and biologic-exposed patients, and the effects of MTX dose on the rates of achievement of low disease activity (LDA) and remission as determined by 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) as efficacy measures were analyzed using the maximum-contrast method [13].

Methods

In the MELODY study, we conducted secondary analyses of central registry data from an all-case postmarketing surveillance study with follow-up periods of 24 weeks for efficacy and 28 weeks for safety [6]. These analyses had been requested by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (MHLW) as a condition for approval of ADA, in accordance with the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law of Japan, and were conducted in compliance with the Good Post-marketing Study Practice (Ordinance No. 171 of the MHLW dated December 20, 2004). In this all-case study, as 2241 patients (2241/7740 patients, 29%) did not use MTX concomitantly with ADA (five patients with unknown MTX dose), we excluded the data from these patients receiving ADA monotherapy to investigate the dose response profile of MTX in 5494 patients with established RA in the clinical setting. The dose of MTX used concomitantly with ADA was calculated as the weighted average adjusted for the duration of ADA therapy during the follow-up period. Patients were classified into the following five groups according to the average weekly dose of concomitant MTX: group 1, >0–<4 mg; group 2, 4–<6 mg; group 3, 6–<8 mg; group 4, 8–<10 mg; and group 5, ≥10 mg.

Among the 5494 patients who received ADA and MTX, 3097 patients who had a baseline DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) of >3.2 were included in the efficacy analysis set. Low disease activity was defined as a DAS28-ESR of ≤3.2, and remission as a DAS28-ESR of <2.6. Missing DAS28-ESR data were imputed by the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as numbers and ratios (%). The relationships between patient background factors and groups were assessed using the Chi-square test for categorical data and the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous data. To identify factors relevant to the dose–response profile of MTX, univariate logistic regression analysis was performed using the effectiveness analysis set (n = 3097) on the factors listed below (step 1), and factors with p < 0.05 were included in the multivariate logistic analysis (step 2). Contrast analysis of the relationship between MTX dose and effectiveness was performed by multivariate logistic regression modeling, including variables selected as factors affecting LDA achievement by week 24 (LOCF method; step 3). The data were adjusted for essential variables, including interactions. In the selected model (n = 3097; Akaike’s information criterion, 3587.7), a maximum-contrast test [13] in each population was performed to establish the dose–response profile of MTX, adjusting for essential variables. To simplify the dose–response profile of MTX, the effectiveness analysis set was divided into biologic-naïve and biologic-exposed patients. Prior biologic treatment was determined to be a significant factor (p < 0.0001) in the multivariate logistic analysis.

Safety Evaluation

For safety evaluation, all adverse events (AEs) were recorded and tabulated based on preferred terms from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 14.0 [14]. The safety endpoints were the incidences of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) for which a causal relationship with ADA could not be ruled out, serious ADRs, infections, and serious infections. The safety analysis for the MELODY study was performed with 5494 of the 7740 patients registered in the all-case postmarketing surveillance study [6]: specifically, all patients except the 2241 patients who did not use MTX concomitantly with ADA and the five patients for whom the MTX dosage was unspecified. The safety endpoints were the incidences of ADRs, serious ADRs, infections, and serious infections. Multiplicity was not considered in the contrast test and Cox regression analysis, as this study was an explanatory study. All tests were two-sided and p < 0.05 was defined as significant, except for interactions (p < 0.10). All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). This article does not contain any new studies with human subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

In this post hoc analysis of the all-case survey with ADA, patients were stratified only by previous use of biologics to assess the effect of MTX dose on patients receiving ADA after the following analysis: In the selected model (n = 3097; Akaike’s information criterion, 3587.7), the essential variables were previous use of biologics (p < 0.0001), baseline DAS28-ESR (p < 0.0001), age (p = 0.0013), Steinbrocker class (p = 0.0004), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.0206), sex (p = 0.0068), group (p = 0.0280), and interaction between age and diabetes mellitus (p = 0.0558) (Data on file, AbbVie GK, Tokyo, Japan). Although both previous use of biologics and baseline DAS28-ESR showed a highly significant effect on the dose–response profile of MTX, baseline DAS28-ESR did not differ by MTX dose.

In the 1996 biologic-naïve patients, there were significant differences among the five MTX dose groups with respect to sex, age, disease duration, renal comorbidities, and percentages in each Steinbrocker stage at baseline. In the 1101 biologic-exposed patients, there were significant differences among the five MTX dose groups with respect to respiratory comorbidities, pulmonary disease history or comorbidity, and percentages in each Steinbrocker class (Tables 1, 2). Mean DAS28-ESR scores at baseline did not differ by MTX dose in either patient population, and both populations had similar scores (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of biologic-naïve RA patients stratified by weekly dose of concomitant MTX (n = 1996)

| Group 1 (n = 97) | Group 2 (n = 284) | Group 3 (n = 580) | Group 4 (n = 819) | Group 5 (n = 216) | p a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, females (%) | 79 (81.4) | 246 (86.6) | 492 (84.8) | 685 (83.6) | 161 (74.5) | 0.0038 |

| Age (y) | 61.1 ± 13.9 | 63.3 ± 11.4 | 60.9 ± 12.5 | 57.6 ± 13.1 | 56.4 ± 13.3 | <0.0001 |

| Duration of RA (y) | 12.5 ± 11.1 | 11.1 ± 10.4 | 9.9 ± 10.4 | 8.3 ± 8.7 | 7.7 ± 8.6 | <0.0001 |

| DAS28-ESR score | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.0 | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 0.2059 |

| Comorbidities | 64 (66.0) | 162 (57.0) | 329 (56.7) | 474 (57.9) | 135 (62.5) | 0.3130 |

| Cardiovascular | 26 (26.8) | 61 (21.5) | 119 (20.5) | 153 (18.7) | 47 (21.8) | 0.3547 |

| Respiratory | 12 (12.4) | 23 (8.1) | 41 (7.1) | 75 (9.2) | 35 (16.2) | 0.0018 |

| Hematologic | 5 (5.2) | 20 (7.0) | 33 (5.7) | 46 (5.6) | 16 (7.4) | 0.7839 |

| Hepatic | 9 (9.3) | 20 (7.0) | 40 (6.9) | 34 (4.2) | 14 (6.5) | 0.0784 |

| Renal | 4 (4.1) | 4 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (1.1) | 3 (1.4) | 0.0083 |

| Others | 49 (50.5) | 124 (43.7) | 254 (43.8) | 367 (44.8) | 104 (48.1) | 0.6240 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (9.3) | 15 (5.3) | 44 (7.6) | 6.2 (7.6) | 13 (6.0) | 0.5663 |

| Pulmonary disease history or comorbidityb | 15 (15.5) | 29 (10.2) | 53 (9.1) | 101 (12.3) | 39 (18.1) | 0.0068 |

| History of allergies | 15 (15.5) | 31 (10.9) | 62 (10.7) | 100 (12.2) | 28 (13.0) | 0.5719 |

| Steinbrocker stage | ||||||

| I | 10 (10.3) | 26 (9.2) | 87 (15.0) | 142 (17.3) | 36 (16.7) | 0.0005 |

| II | 21 (21.6) | 89 (31.3) | 162 (27.9) | 228 (27.8) | 78 (36.1) | |

| III | 23 (23.7) | 75 (26.4) | 159 (27.4) | 236 (28.8) | 51 (23.6) | |

| IV | 43 (44.3) | 94 (33.1) | 172 (29.7) | 213 (26.0) | 51 (23.6) | |

| Steinbrocker class | ||||||

| I | 12 (12.4) | 41 (14.4) | 90 (15.5) | 126 (15.4) | 25 (11.6) | 0.0002 |

| II | 60 (61.9) | 162 (57.0) | 361 (62.2) | 535 (65.3) | 160 (74.1) | |

| III | 19 (19.6) | 75 (26.4) | 118 (20.3) | 150 (18.3) | 30 (13.9) | |

| IV | 6 (6.2) | 6 (2.1) | 11 (1.9) | 8 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Previous biologic therapy | ||||||

| None (biologic-naïve) | 97 (100.0) | 284 (100.0) | 580 (100.0) | 819 (100.0) | 216 (100.0) | NR |

| Infliximab only | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Etanercept only | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Infliximab and etanercept | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Others | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other prior medication | ||||||

| GCs > 5 mg/day | 14 (14.4) | 33 (11.6) | 73 (12.6) | 113 (13.8) | 35 (16.2) | 0.7226 |

| GCs > 7.5 mg/day | 7 (7.2) | 14 (4.9) | 28 (4.8) | 50 (6.1) | 19 (8.8) | 0.4541 |

| DMARDs (excluding MTX) | 35 (36.1) | 94 (33.1) | 147 (25.3) | 195 (23.8) | 50 (23.1) | 0.0036 |

Group 1, >0–<4 mg; group 2, ≥4–<6 mg; group 3, ≥6–<8 mg; group 4, ≥8–<10 mg; group 5, ≥10 mg/week. Values are means ± SD or n (%). aChi-square test for categorical variables, Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. bIncludes patients with a past or current history of pulmonary disease (e.g., pneumonia, asthma, and obstructive pulmonary disease) and those with abnormal chest radiographic findings. A weighted average dose was used to calculate mean MTX dose. DAS28-ESR disease activity score for 28 joints based on the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, DMARDs disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, GCs glucocorticoids, MTX methotrexate, NR not reported, RA rheumatoid arthritis

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of biologic-exposed RA patients stratified by weekly dose of concomitant MTX (n = 1101)

| Group 1 (n = 84) | Group 2 (n = 175) | Group 3 (n = 349) | Group 4 (n = 369) | Group 5 (n = 124) | p a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, females (%) | 76 (90.5) | 149 (85.1) | 304 (87.1) | 317 (85.9) | 101 (81.5) | 0.4066 |

| Age (y) | 61.3 ± 11.3 | 61.1 ± 12.7 | 59.6 ± 11.9 | 56.8 ± 12.8 | 53.4 ± 13.5 | <0.0001 |

| Duration of RA (y) | 13.9 ± 9.8 | 12.0 ± 9.4 | 11.9 ± 9.5 | 10.6 ± 8.3 | 8.8 ± 7.5 | 0.0004 |

| DAS28-ESR score | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 0.8663 |

| Comorbidities | 54 (64.3) | 122 (69.7) | 216 (61.9) | 225 (61.0) | 68 (54.8) | 0.1132 |

| Cardiovascular | 12 (14.3) | 52 (29.7) | 71 (20.3) | 76 (20.6) | 18 (14.5) | 0.0086 |

| Respiratory | 8 (9.5) | 20 (11.4) | 30 (8.6) | 34 (9.2) | 12 (9.7) | 0.8894 |

| Hematologic | 6 (7.1) | 16 (9.1) | 33 (9.5) | 33 (8.9) | 11 (8.9) | 0.9781 |

| Hepatic | 4 (4.8) | 12 (6.9) | 18 (5.2) | 18 (4.9) | 8 (6.5) | 0.8642 |

| Renal | 5 (6.0) | 7 (4.0) | 3 (0.9) | 5 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0017 |

| Others | 45 (53.6) | 105 (60.0) | 174 (49.9) | 187 (50.7) | 55 (44.4) | 0.0841 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (6.0) | 17 (9.7) | 29 (8.3) | 27 (7.3) | 11 (8.9) | 0.8161 |

| Pulmonary disease history or comorbidityb | 14 (16.7) | 26 (14.9) | 39 (11.2) | 39 (10.6) | 15 (12.1) | 0.4064 |

| History of allergies | 19 (22.6) | 33 (18.9) | 69 (19.8) | 70 (19.0) | 21 (16.9) | 0.9103 |

| Steinbrocker stage | ||||||

| I | 6 (7.1) | 7 (4.0) | 15 (4.3) | 32 (8.7) | 16 (12.9) | 0.0058 |

| II | 11 (13.1) | 46 (26.3) | 81 (23.2) | 83 (22.5) | 32 (25.8) | |

| III | 24 (28.6) | 52 (29.7) | 113 (32.4) | 121 (32.8) | 42 (33.9) | |

| IV | 43 (51.2) | 70 (40.0) | 140 (40.1) | 133 (36.0) | 34 (27.4) | |

| Steinbrocker class | ||||||

| I | 6 (7.1) | 8 (4.6) | 33 (9.5) | 43 (11.7) | 12 (9.7) | 0.3818 |

| II | 50 (59.5) | 112 (64.0) | 214 (61.3) | 231 (62.6) | 80 (64.5) | |

| III | 26 (31.0) | 48 (27.4) | 95 (27.2) | 87 (23.6) | 31 (25.0) | |

| IV | 2 (2.4) | 7 (4.0) | 7 (2.0) | 8 (2.2) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Previous biologic therapy | ||||||

| None (biologic-naïve) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Infliximab only | 17 (20.2) | 51 (29.1) | 142 (40.7) | 151 (40.9) | 65 (52.4) | <0.0001 |

| Etanercept only | 41 (48.8) | 80 (45.7) | 126 (36.1) | 131 (35.5) | 28 (22.6) | |

| Infliximab and etanercept | 9 (10.7) | 17 (9.7) | 51 (14.6) | 50 (13.6) | 19 (15.3) | |

| Any others | 17 (20.2) | 27 (15.4) | 30 (8.6) | 37 (10.0) | 12 (9.7) | |

| Other prior medication | ||||||

| GCs > 5 mg/day | 14 (16.7) | 27 (15.4) | 56 (16.0) | 72 (19.5) | 30 (24.2) | 0.0854 |

| GCs > 7.5 mg/day | 10 (11.9) | 11 (6.3) | 21 (6.0) | 31 (8.4) | 11 (8.9) | 0.0886 |

| DMARDs (excluding MTX) | 24 (28.6) | 45 (25.7) | 68 (19.5) | 73 (19.8) | 29 (23.4) | 0.1987 |

Group 1, >0–< 4 mg; group 2, ≥4–<6 mg; group 3, ≥6–<8 mg; group 4, ≥8–<10 mg; group 5, ≥10 mg. Values are means ± SD or n (%). aChi-square test for categorical variables, Kruskal–Wallis test used for continuous variables. bIncludes patients with a past or current history of pulmonary disease (e.g., pneumonia, asthma, and obstructive pulmonary disease) and those with abnormal chest radiographic findings. A weighted average dose was used to calculate mean MTX dose. DAS28-ESR disease activity score for 28 joints based on the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, DMARDs disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, GCs glucocorticoids, MTX methotrexate, RA rheumatoid arthritis

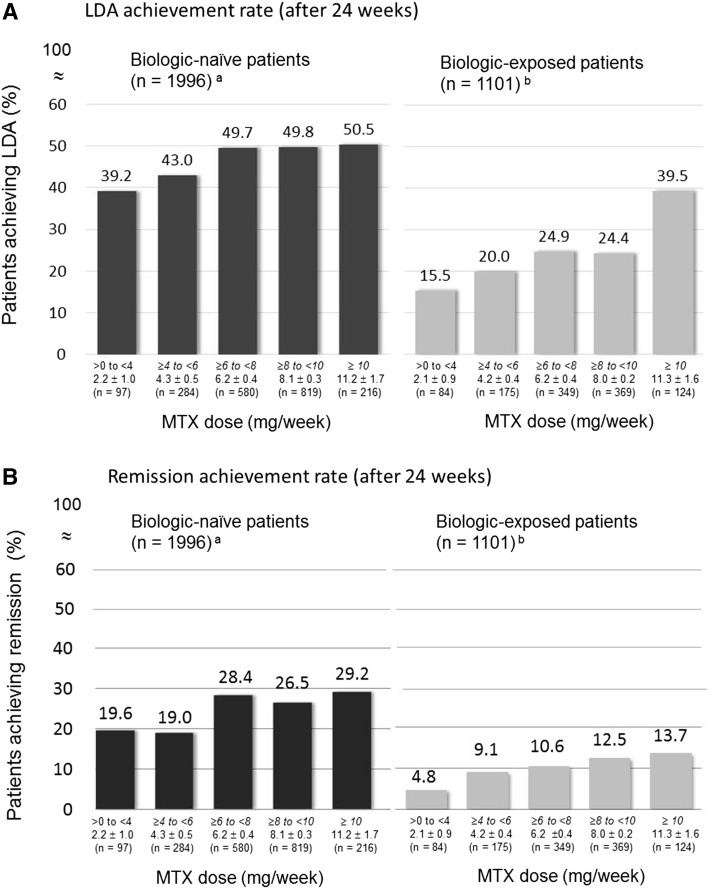

LDA and remission rates at week 24 are summarized in Fig. 1. In the 1996 biologic-naïve patients, LDA rates were 39.2, 43.0, 49.7, 49.8, and 50.5% in groups 1 through 5, respectively (Fig. 1A, left), and remission rates were 19.6, 19.0, 28.4, 26.5, and 29.2%, respectively (Fig. 1B, left). There was a tendency toward a dose-dependent increase in both LDA and remission rates among groups 1, 2, and 3; however, the rates did not increase further in groups 4 and 5. A contrast test adjusted for differences in baseline patient characteristics revealed that the LDA and remission rates by MTX dose in biologic-naïve patients were in the order group 1 < group 2 < group 3 = group 4 = group 5 (LDA, p = 0.0440; remission, p = 0.0422). In the 1101 biologic-exposed patients, in contrast, LDA rates were 15.5, 20.0, 24.9, 24.4, and 39.5% in groups 1 through 5, respectively (Fig. 1A, right), and remission rates were 4.8, 9.1, 10.6, 12.5, and 13.7%, respectively (Fig. 1B, right). The contrast test also revealed that LDA and remission rates by MTX dose in biologic-exposed patients were in the order group 1 < group 2 < group 3 < group 4 < group 5 (LDA, p = 0.0009; remission, p = 0.0143).

Fig. 1.

Percentages of patients achieving LDA (A) and remission rate (B) after treatment with MTX and adalimumab for 24 weeks. Patients were stratified by weighted average dose of concomitant weekly MTX as follows: group 1, >0–<4 mg; group 2, 4–<6 mg; group 3, 6–<8 mg; group 4, 8–<10 mg; and group 5, ≥10 mg; one degree of freedom for each. aAIC, 2479.177. Contrast test results adjusted for baseline DAS28-ESR (continuous), age (1: <20 years, 2: 20–29 years, 3: 30–39 years, 4: 40–49 years, 5: 50–59 years, 6: 60–69 years, 7: 70–79 years, and 8: ≥80 years; continuous), class (I–II, III–IV), previous or coexisting diabetes mellitus (yes, no), and sex. Patients received any biologic treatment other than adalimumab before starting adalimumab treatment; bAIC, 1116.088. Contrast test results adjusted for baseline DAS28-ESR (continuous), class (I–II, III–IV), sex, and past biologic treatment (infliximab only, etanercept only, both infliximab and etanercept, and any others). AIC, Akaike’s information criterion. DAS28-ESR disease activity score for 28 joint counts based on the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, LDA low disease activity, MTX methotrexate. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation

With respect to safety evaluation of the 5494 patients receiving ADA and MTX, neither serious ADRs nor serious infections differed significantly across the five groups. The incidence of ADRs was significantly higher in group 1 than in the other groups. The incidence of infections was significantly higher in group 5 than in groups 2, 3, and 4 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adverse drug reactions in adalimumab-treated RA patients by weekly MTX dose (n = 5494)

| Group 1 (n = 356) | Group 2 (n = 894) | Group 3 (n = 1651) | Group 4 (n = 2005) | Group 5 (n = 588) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADRs | |||||

| n, (%) | 111 (31.2) | 201 (22.5) | 367 (22.2) | 409 (20.4) | 137 (23.3) |

| p value (vs. Group 1)a | NR | 0.0022 | 0.0009 | <0.0001 | 0.0148 |

| p value (vs. Group 2)a | NR | 0.9735 | 0.2816 | 0.6537 | |

| p value (vs. Group 3)a | NR | 0.1822 | 0.6400 | ||

| p value (vs. Group 4)a | NR | 0.1482 | |||

| Serious ADRs | |||||

| n, (%) | 19 (5.3) | 35 (3.9) | 66 (4.0) | 85 (4.2) | 19 (3.2) |

| p value (vs. Group 1)b | NR | 0.2509 | 0.4077 | 0.6596 | 0.2256 |

| p value (vs. Group 2)b | NR | 0.5949 | 0.2897 | 0.8135 | |

| p value (vs. Group 3)b | NR | 0.3933 | 0.4669 | ||

| p value (vs. Group 4)b | NR | 0.2670 | |||

| Infection | |||||

| n, (%) | 34 (9.6) | 57 (6.4) | 97 (5.9) | 140 (7.0) | 61 (10.4) |

| p value (vs. Group 1)c | NR | 0.0831 | 0.0310 | 0.2111 | 0.4343 |

| p value (vs. Group 2)c | NR | 0.7408 | 0.3874 | 0.0032 | |

| p value (vs. Group 3)c | NR | 0.1480 | 0.0003 | ||

| p value (vs. Group 4)c | NR | 0.0080 | |||

| Serious infection | |||||

| n, (%) | 13 (3.7) | 19 (2.1) | 26 (1.6) | 49 (2.4) | 12 (2.0) |

| p value (vs. Group 1)d | NR | 0.2106 | 0.1056 | 0.7095 | 0.5138 |

| p value (vs. Group 2)d | NR | 0.7647 | 0.2170 | 0.5903 | |

| p value (vs. Group 3)d | NR | 0.0683 | 0.3950 | ||

| p value (vs. Group 4)d | NR | 0.2052 | |||

Group 1, >0–<4 mg; group 2, ≥4–<6 mg; group 3, ≥6–<8 mg; group 4, ≥8–<10 mg; group 5, ≥10 mg. aThe analysis was conducted with a stepwise Cox regression analysis, including 5491 patients from the safety population (n = 5494). Group, Steinbrocker’s stage (I and II vs. III and IV), past history of tuberculosis, respiratory comorbidity, cardiovascular comorbidity, and hematologic comorbidity were included in a stepwise Cox regression model. bThe analysis was conducted with a stepwise Cox regression analysis, including 5493 patients from the safety population (n = 5494). Age (per 10 years), sex, comorbidity of respiratory and comorbidity of hematologic were included in a stepwise Cox regression model. cThe analysis was conducted with a stepwise Cox regression analysis, including 5491 patients from the safety population (n = 5494). Group, Steinbrocker’s stage (I and II vs. III and IV), past history of interstitial pneumonia, and cardiovascular comorbidity were included in a stepwise Cox regression model. dThe analysis was conducted with a stepwise Cox regression analysis, including 5400 patients from the safety population (n = 5494). Age (per 10 years), Steinbrocker’s stage (I and II vs. III and IV), past history of interstitial pneumonia, cardiovascular comorbidity, hematologic comorbidity, and prior medication with glucocorticoids (none, >0–≤5 mg/day, >5 mg/day) were included in a stepwise Cox regression model. A weighted average was used to calculate mean MTX dose. ADRs adverse drug reactions, MTX methotrexate, NR not reported, RA rheumatoid arthritis

Discussion

The major finding from post hoc analysis of the MELODY study is that in biologic-naïve patients, MTX in combination with ADA increased LDA and remission rates at week 24 up to a MTX dose of 6–<8 mg/week and then plateaued at higher doses, whereas in biologic-treated patients there was a dose-dependent increase up to ≥10 mg/week of MTX. The dose–response profile in the biologic-naïve patients appears similar to that observed in the CONCERTO trial [11]. In that trial, biologic-naïve patients who received MTX in combination with ADA were evaluated for the MTX dose–response of the therapeutic outcomes, including LDA, and there was a statistically significant trend toward better clinical outcomes at higher MTX doses, although no differences were observed in clinical, radiographic, and functional responses between 10 and 20 mg/week of MTX. However, these results suggest that for patients with prior treatment with biologics, MTX dose increase in combination with biologics should be carefully considered.

In the safety analysis, despite no differences in serious ADRs or serious infections, the incidence of ADRs and infections differed significantly between lower- and higher-dose MTX groups. The significantly higher incidence of infections in patients of group 5, who received the highest MTX dose in our study, was consistent with findings from the previous safety analysis of the all-case study [6]. That analysis revealed that the use of MTX at >8 mg/week represents a risk factor for infections, respiratory infections, severe respiratory infections, and pneumonia. In the present analysis, incidences of ADRs and infections were also significantly higher in patients of group 1 who received MTX at the lowest dose range. Patients of group 1 tended to be older, had longer disease duration, and more concomitant diseases, which are factors for higher risk of ADRs and infections.

As a post hoc analysis of an observational study, this study had several limitations. Of note, the Japan College of Rheumatology has published its guidelines for the use of MTX in the treatment of RA, including the supplementation with folic acid, and, in the present study, Japanese patients with RA were treated accordingly. First, the dose of MTX could be changed whenever necessary during combination treatment with ADA. Second, although we adjusted the contrast tests for differences in baseline data, baseline characteristics of patients were different among the groups. Third, as outcome measures available for analysis depend on the original all-case survey, no radiologic or functional data were analyzed in this study, and the efficacy of treatment was analyzed only with clinical measures. A direct comparison between our findings with and those in non-Japanese populations could not be made. To confirm these data in the Japanese population, a randomized clinical study is needed. To date, there is no scientifically sound explanation for the observation that biologic-exposed patients need higher doses of MTX than biologic-naïve patients to achieve LDA and remission. To address this question in a future study, we must measure disease activity more accurately and use a more clinically relevant endpoint.

Conclusion

In the treatment of RA, the effects of MTX in combination with ADA on LDA and remission rates showed a different dose–response profile between biologic-naïve and biologic-exposed patients. In biologic-naïve patients, the effects of MTX plateaued at a dose of 6–<8 mg/week, suggesting that 8 mg/week is sufficient for this patient population.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were funded by AbbVie GK, Tokyo, Japan (formerly Abbott Japan Co., Ltd., Japan) and Eisai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, who provided funds for data collection. AbbVie contributed to the design of the study, the data analysis and interpretation, and in the drafting, review, and approval of the manuscript.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

We express our sincere thanks to the participating investigators, fellows, nurses, and research coordinators at each medical institution. We also deeply thank the patients who participated in this study for their contribution. We thank Jungo Sawa, Ph.D., a contracted biostatistician of AbbVie GK, for his dedicated support in the development of the statistics plan and interpretation of the results. We also thank Naoki Agata, Ph.D. and Sarina Kurimoto, M.D., Ph.D. for critical review of this work, and Rie Moriguchi, R&A Medical Translation Service, who provided medical writing support on behalf of AbbVie.

Part of the work was presented in an abstract form at the 59th Annual General Assembly and Scientific Meeting of the Japan College of Rheumatology (on April 24, 2015 in Nagoya, Japan).

Disclosures

Doctors T. Koike, M. Harigai, N. Ishiguro, S. Inokuma, S. Takei, T. Takeuchi, H. Yamanaka, and Y. Tanaka are members of the Postmarketing Surveillance (PMS) Committee of the Japan College of Rheumatology. It is the belief of the authors that this does not constitute a conflict of interest. The doctors participated in review and analysis of the PMS data in their capacity as committee members. The financial relationships of the authors with manufacturers of biological products used in the management of RA are as listed. T. Koike has received consultancies, speaking fees, and honoraria from Abbott Japan, AbbVie GK, Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Santen Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Teijin Pharmaceutical, and Pfizer. M. Harigai has received research grants, speaking fees, or honoraria from Abbott Japan, AbbVie GK, Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eisai Pharmaceutical, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Santen Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, UCB Japan, and Pfizer and has received consultant fees from Abbott Japan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Janssen Pharmaceutical. N. Ishiguro has received research grants from AbbVie GK, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Eisai Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Pfizer Japan Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. S. Inokuma has nothing to disclose. S. Takei has received research grants, consulting fees, and/or speaking fees from Eisai, Chugai, Takeda, Bristol-Myers K.K., Teijin, Pfizer, Mylan, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Asahi Kasei, and Astellas. T. Takeuchi has received grants from AbbVie GK, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Nippon Shinyaku Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Sanofi K.K., Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and Teijin Pharma Limited, has received speaking fees from AbbVie GK, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Eisai Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Pfizer Japan Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and has received consultant fees from AstraZeneca K.K., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Novartis Pharma K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, and Asahi Kasei Medical Co., Ltd. H. Yamanaka has received research grants from AbbVie GK, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Eisai Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer Japan Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and UCB Japan Co., Ltd., and has received speaker honoraria/consulting fees from AbbVie GK, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Eisai Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer Japan Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and UCB Japan Co., Ltd. Y. Takasaki has received grants and research from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca plc, Astellas Pharma Inc., MSD K.K., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, Eisai Co., Ltd., and Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K. T. Mimori has received grant and research support from Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, Astellas Pharma Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Merck & Co., Inc., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Pfizer Japan Inc., Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and is on the speakers’ bureaus for Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Pfizer Japan Inc., Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Y. Tanaka has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from AbbVie GK, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Astellas Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Pfizer Japan Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Eisai Co., Ltd., Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., UCB Japan Co., Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline K.K., and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and has received research grants from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., MSD K.K., Astellas Pharma, and Novartis Pharma K.K. K. Hiramatsu and S. Komatsu are full-time employees of AbbVie GK and may have AbbVie stock or stock options.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40744-015-0023-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Koeller M, Weisman MH, Emery P. New therapies for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2007;370:1861–1874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Redlich K. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: new insights from old clinical data? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:235–243. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Christensen R, Wells GA, et al. Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD007848. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007848.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtis JR, Singh JA. Use of biologics in rheumatoid arthritis: current and emerging paradigms of care. Clin Ther. 2011;33:679–707. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of the first 3000 patients. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:498–508. doi: 10.3109/s10165-011-0541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of 7740 patients. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:390–398. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2013.843760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seto Y, Tanaka E, Inoue E, et al. Studies of the efficacy and safety of methotrexate at dosages over 8 mg/week using the IORRA cohort database. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21:579–593. doi: 10.3109/s10165-011-0445-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492–509. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:26–37. doi: 10.1002/art.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, Kaneko Y, et al. Effectiveness and safety of adalimumab in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: retrospective analyses of data collected during the first year of adalimumab treatment in routine clinical practice (HARMONY study) Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:327–338. doi: 10.3109/s10165-011-0516-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burmester GR, Kivitz AJ, Kupper H, et al. Efficacy and safety of ascending methotrexate dose in combination with adalimumab: the randomised CONCERTO trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;74:1037–1044. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaeley GS, Evangelisto AM, Nishio MJ, et al. Impact of methotrexate dose reduction upon initiation of adalimumab on clinical and ultrasonographic parameters in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2014;53(suppl 1):i86–i87. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu101.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimura I, Wakana A. A performance comparison of maximum contrast methods to detect dose dependency. Drug Inf J. 1997;31:423–432. doi: 10.1177/009286159703100213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Steering Committee. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Clinical safety data management: definitions and standards for expedited reporting. http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000156018.pdf. Accessed 21 May 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.