INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated and antigen-mediated disorder characterized by an isolated eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus resulting in esophageal dysfunction.1 Although there are many causes of esophageal eosinophilia, EoE must be primarily distinguished from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and proton-pump inhibitor (PPI)–responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE). EoE is an emerging disorder associated with other allergic conditions2 and currently affects approximately 56.7 per 100,000 people in the United States.3 EoE pathophysiology is complex, involving a variety inflammatory cells and cytokines in a non–immunoglobulin E (IgE)-dependent allergic model.4–6 EoE is primarily caused by the ingestion of one or more food antigens,7, 8 but may also be triggered by inhaled aeroantigens.9 EoE and associated complications have a significant impact on patient quality of life10 and patients with EoE in the United States have an annual health care cost of up to $1.4 billon.11 EoE therapy is limited to dietary modification, steroids, and endoscopic dilatation.1 At present, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the gold standard for diagnosis and disease monitoring.

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS DIAGNOSIS AND SURVEILLANCE

EoE requires a clinicopathologic diagnosis. EGD is often performed in children for a variety of reasons, including chronic reflux symptoms with or without a poor response to acid suppression therapy, feeding problems, poor growth, intermittent or persistent vomiting and regurgitation, chest or epigastric abdominal pain, gastric or duodenal ulcers, dysphagia, a history of food impaction, or any other chronic indication of esophageal or gastric dysfunction. Because the current gold standard for the diagnosis of EoE is histologic evidence of esophageal eosinophilia, when performing an EGD it is paramount to perform biopsies, even in the presence of normal-looking mucosa.1

Endoscopic Findings

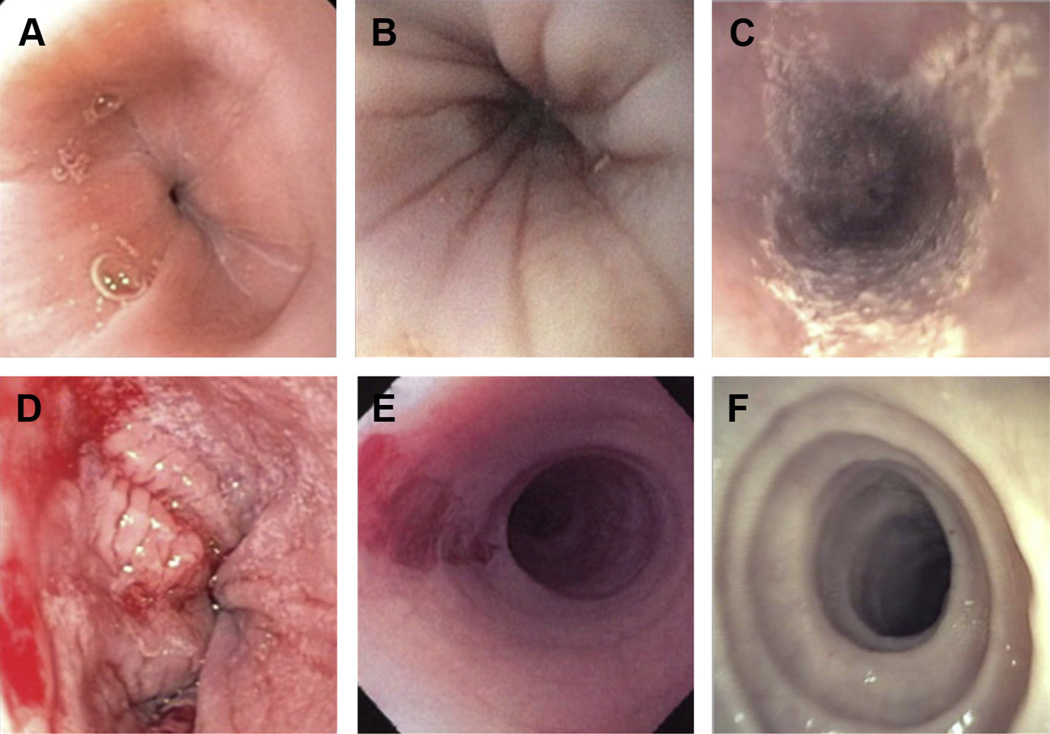

Although there are no pathognomonic findings for EoE, esophageal edema, longitudinal furrows, mucosal fragility, whitish exudates, transient esophageal rings (feline folds), fixed esophageal rings (trachealization), diffuse esophageal narrowing, and small-caliber esophagus are its typical macroscopic findings (Fig. 1).1 Up to one-third of children with EoE may have visually normal esophageal mucosa.12

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic findings of EoE. (A) Normal esophageal mucosa. (B) Esophageal furrowing. (C) Esophageal white mucosal plaques. (D) Esophageal mucosal fragility in a patient with EoE after biopsy. (E) Esophageal mucosal fragility with so-called crepe paper esophagus. (F) Esophageal trachealization. (Courtesy of [C, E, F] The International Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Researchers (TIGERS) and Children’s Digestive Health and Nutrition Foundation (CDHNF) slide set; and [E] Chris A. Liacouras, MD, Philadelphia, PA.)

A novel endoscopic classification and grading system called the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS) was recently developed and validated in adults to define common nomenclature, severity description, and disease assessment among providers. 13 The EREFS score is generated based on the presence and/or severity of transient or fixed esophageal rings, exudates, furrowing, mucosal fragility (so-called crepe-paper esophagus), edema (and the associated vascular pattern), as well as stricture.13 Although this system has good interobserver agreement between practitioners, a validated scoring system in children has yet to be established.

There are many past and present differences in EoE diagnostic practices between pediatric and adult gastroenterologists. For example, adult gastroenterologists have traditionally based the diagnosis of esophageal disorders primarily on symptoms and endoscopic findings, rather than histolopathology.14 Alternatively, pediatric gastroenterologists have been trained to obtain mucosal biopsies in all diagnostic procedures, even if the mucosa is visually normal. The pediatric approach to diagnosis may be extremely important to identifying the presence of EoE, because it is common for patients of all ages to have a normal-appearing esophagus.12

Radiology

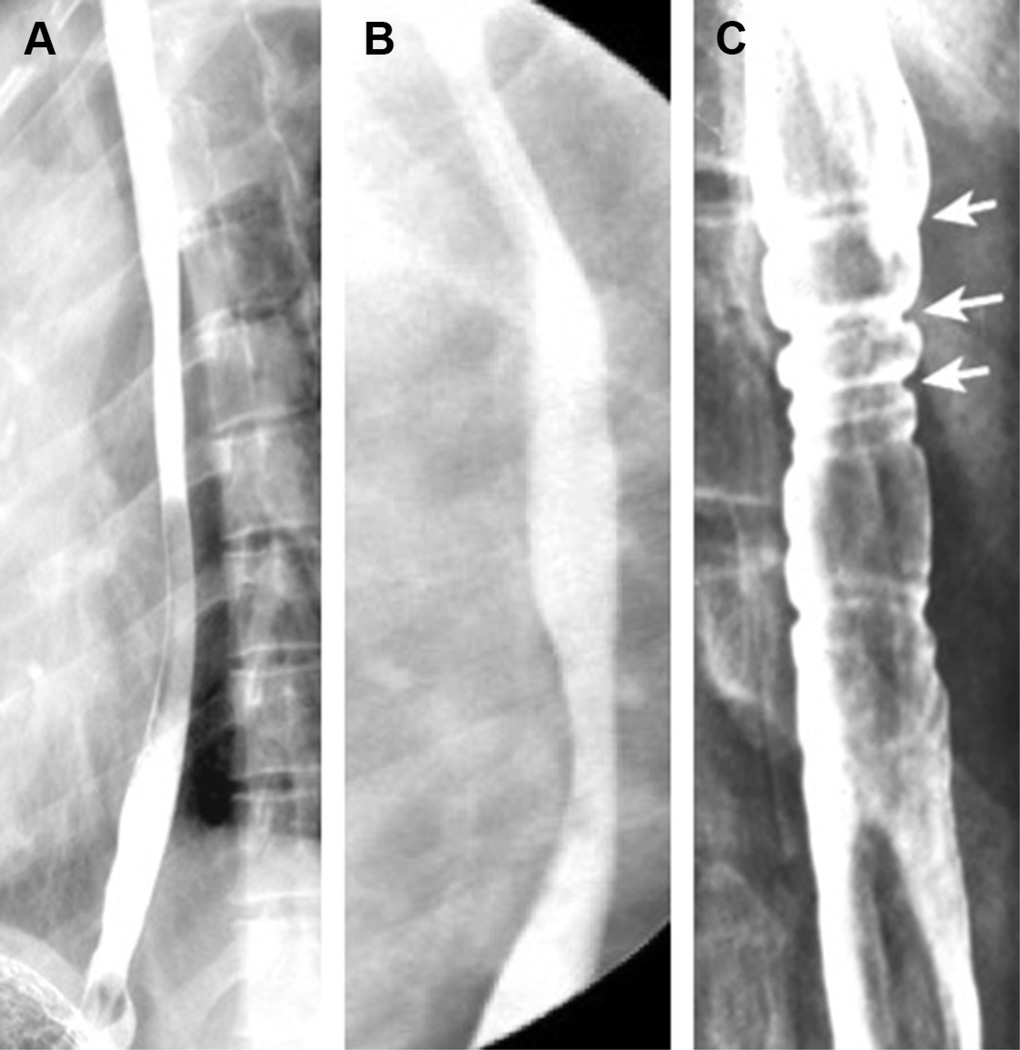

Although not recommended routinely for EoE diagnosis, imaging with upper gastrointestinal intestinal series (UGI) or esophagram should be recognized to be a useful test in patients with feeding problems, dysphagia, or food impaction to evaluate for anatomic and mucosal abnormalities such as narrowing, stricture, or formation of rings (Fig. 2).1, 15, 16 In a cohort of 22 pediatric patients with EoE with strictures who underwent esophagram and endoscopy within 3 months of each other, 12 had esophageal strictures identified by esophagram alone and only 1 had a stricture identified by endoscopy but not esophagram.16 Furthermore, 3 of 4 patients who received a barium pill had evidence of impaction or delayed pill transit.16 Although not specific to EoE, these findings may provide valuable adjunctive monitoring and diagnostic information before performing an upper endoscopy. Characterizing a patients’ anatomy may also be useful in preventing unwanted complications, including esophageal perforation. Patients with EoE may be at risk for perforation with instrumentation, and have been described as having crepe-paper esophagus.

Fig. 2.

Esophagram findings of EoE. (A) Diffuse esophageal narrowing. (B) Esophageal stricture with 2 pronounced areas of narrowing. (C) Esophageal rings indicated by white arrows. (Courtesy of [A, C] TIGERS and CDHNF slide set.)

Histology

EoE is a diagnosis that requires both clinical symptoms (isolated esophageal dysfunction) and abnormal histology, with greater than or equal to 15 esophageal eosinophils per high-power field in the most densely involved esophageal mucosal specimens. Eosinophils are not increased in any other part of the gastrointestinal tract. EoE often presents as a patchy disease, thus multiple biopsies are required. According to several recent guidelines, multiple biopsies should be obtained from both the mid/ proximal and distal esophagus of patients who are being concomitantly treated with high-dose PPI therapy for 8 to 12 weeks before endoscopy.1, 15

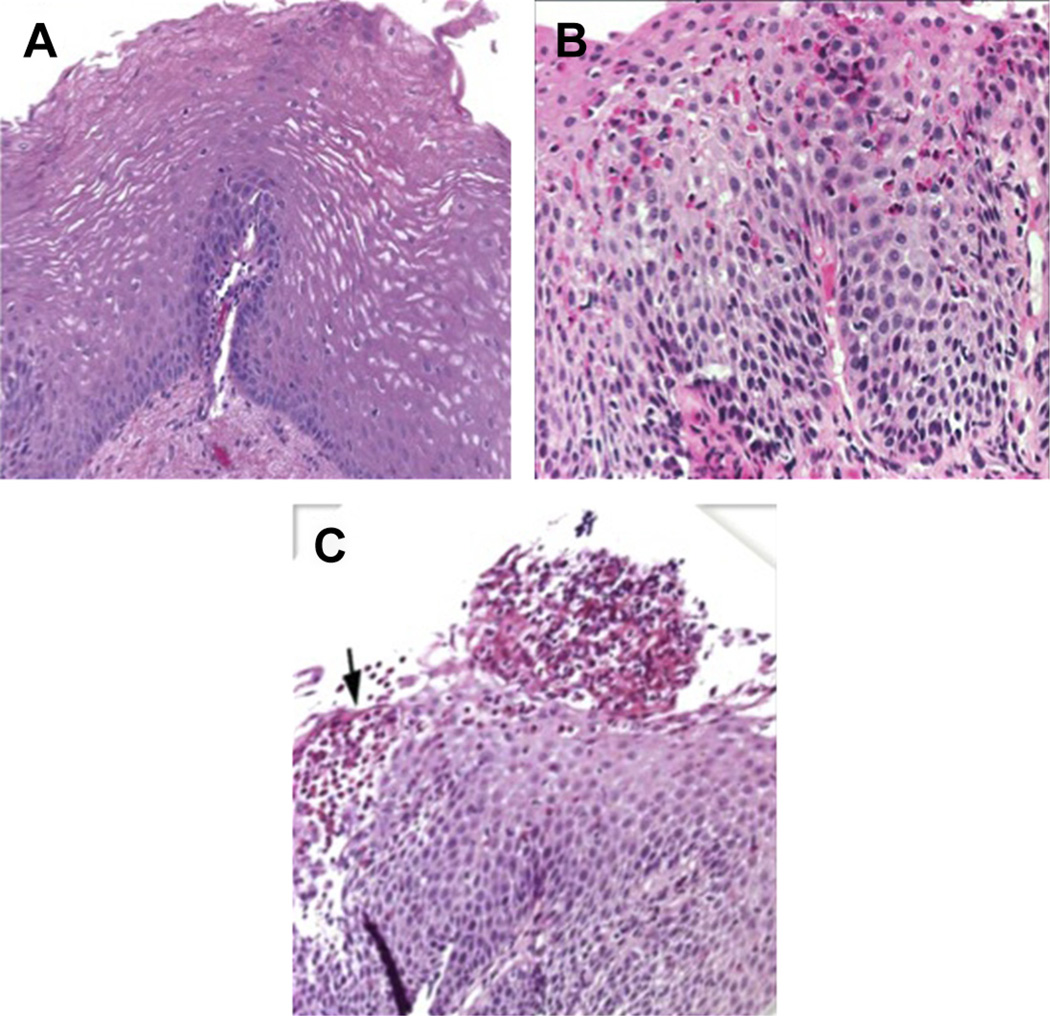

Common microscopic findings of EoE are shown in Fig. 3. Although the eosinophil is the predominant cell type seen on hematoxylin-eosin staining, additional microscopic findings, such as basal cell hyperplasia with resulting acanthosis, eosinophilic microabscess formation and layering, eosinophilic granules, dilated intercellular spaces, as well as thickened and dense lamina propria fibers, have also been reported.1, 17, 18 In addition to eosinophils, the feature and predominant inflammatory cells of EoE, many other cell types, including mast cells, basophils, and both B and T lymphocytes, have been discovered in the inflammatory milieu.1, 17, 19 A unique inflammatory cytokine and genetic profile has also been identified in human esophageal mucosal biopsies from patients with EoE.20–22

Fig. 3.

Histology of the esophagus. (A) Normal esophagus (B) EoE esophagus with basal cell hyperplasia and eosinophilic infiltrate. (C) EoE esophagus with superficial layering of eosinophils (black arrow) and an eosinophilic abscess. Histologic evaluation of the esophagus by hematoxylin and eosin stain. (Courtesy of [C] TIGERS and CDHNF slide set.)

Recent guidelines have stressed the importance of making the distinction between esophageal eosinophilia and EoE. Esophageal eosinophilia is a descriptive term, whereas EoE is a disease and diagnosis. There are many causes of esophageal eosinophilia, including GERD; PPI-REE; bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections; Crohn disease; primary immune deficiencies; other hypereosinophilic disorders; connective tissue disorders; and side effects of various medications.23 There may be a some patients with EoE who do not meet the threshold of eosinophils for EoE diagnosis either because of inadequate biopsies and sampling error or partial treatment response, although these patients may have other characteristic histologic features.1

Eosinophilic Esophagitis Treatment

After establishing a diagnosis of EoE and initiating therapy, surveillance endoscopy is performed to evaluate for esophageal mucosal healing. At present, there are no other methods that can be used to evaluate the severity of esophageal inflammation. The frequency of endoscopic monitoring varies based on selected therapy. In general, it is recommended that repeat EGD with biopsy be performed to evaluate for response any time a therapy is initiated or altered, because clinical symptoms and histologic inflammation do not correlate.24

Dietary therapy

Dietary elimination of causative foods is an effective treatment strategy to address the inflammation associated with EoE and may reverse esophageal fibrosis.25 Dietary elimination should be considered in all children diagnosed with EoE.1 Dietary management strategies range from empiric elimination of 1 or more antigenic proteins (typically milk, wheat, soy, egg) to a targeted dietary elimination based on an allergy evaluation or the strict use of an elemental diet.8, 26, 27 The use of an amino acid–based formula, thought to be the most efficacious of all EoE therapies, needs to be carefully considered secondary to the significant lifestyle changes and costs related to this therapy. The option chosen should be based on the likelihood of compliance and the patient’s lifestyle and resources.1 When any type of dietary therapy is chosen, consultation with a dietician should be considered to ensure appropriate nutrition in children on elimination diets.1

Endoscopy plays a major role in evaluating the effectiveness of dietary therapy. In many centers, follow-up endoscopy is typically performed 8 to 12 weeks after a change in dietary therapy to evaluate for histologic changes. Dietary therapy has been shown to significantly reverse endoscopic and histologic esophageal abnormalities. 8, 25 Once remission is achieved, no further EGD with biopsies is required, unless and until symptoms recur and/or foods are reintroduced.

Corticosteroid therapy

Both systemic and topical corticosteroid therapies have been shown to be effective strategies for EoE management, and both may reverse fibrosis, although disease typically recurs upon discontinuation of either.28 Although systemic corticosteroids can be considered in severe presentations,1, 29 swallowed topical corticosteroids are most commonly used as therapy for EoE30–32 based on their lower bioavailability and risk of systemic side effects, although local fungal infection remains a concern.33 Fluticasone is sprayed via a metered-dose inhaler directly into the mouth without a spacer and swallowed twice per day.29, 34 Budesonide can be administered as an oral viscous slurry.33, 35 Recommended dosing for these medications is outlined in recent guidelines.1

Similar to dietary therapy, EGD with biopsy is required not only after starting swallowed topical steroid therapy but also after changes in dosing. Although there are no established guidelines, most practitioners perform endoscopy no sooner than 8 to 12 weeks after steroid initiation to ensure response.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis Surveillance

How to decide when and how often to perform EGD with biopsy for surveillance of patients with a known diagnosis of EoE is currently not well understood. Because of the invasive nature of endoscopy, patient concerns, possible anesthesia side effects, and increased medical costs, some investigators argue to limit the number of endoscopies. In contrast, limiting these procedures can often delay therapeutic changes such as expanding a patient’s diet or decreasing medication doses.

Moreover, although some physicians use patient symptoms to guide clinical management, the general lack of correlation between clinical symptoms and tissue inflammation in EoE has been well shown,24 and this approach can often misguide therapeutic decision making. Although in a few cases clinical symptoms and histologic changes have been shown to coincide, this is not typical of most patients. Until less invasive diagnostic tools are available, physicians should recognize the limitations of clinical symptoms for guiding management, and make appropriate decisions regarding the timing of EGD with biopsy.

THERAPEUTIC ROLE OF ENDOSCOPY IN EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

Emergent Procedures in Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Food impaction accounts for up to 10% of pediatric esophageal foreign bodies36 and is considered one of the classic disease presentations of EoE in adults.37, 38 Retrospective pediatric and adult studies suggest that approximately half of all food impactions requiring endoscopy are likely secondary to EoE.38, 39

Patients with food impaction typically present with nausea, odynophagia, substernal chest pain, and salivation. Almost all food impactions are secondary to meat.36, 40 Nevertheless, all patients with suspected food impaction should undergo chest radiograph to rule out other radio-opaque foreign bodies and other complications of ingestion, such as pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax,40 specifically in the pediatric population, in which patient history may be unreliable. In addition, surgical or otolaryngologic consultation should be considered for patients with proximal foreign bodies, which may be removed more successfully with a rigid endoscope rather than with a flexible instrument.

There has been recent controversy among gastroenterologists regarding whether or not to biopsy at the time of endoscopic food removal. Many patients who present with a food impaction may also have esophageal trachealization, furrows, or white plaques on the esophageal mucosa. In many of these cases, patients who present with impactions are not on a PPI, and physicians may erroneously presume that the endoscopic findings are pathognomonic for EoE. However, this is now appreciated to not be the case. A significant number of these patients respond effectively to treatment with PPI, and in turn have a diagnosis of PPI-REE. Thus, making a formal diagnosis of EoE during the initial EGD for a foreign body impaction in the absence of acid suppression can be challenging unless the EGD is repeated after the patient has been treated with high-dose PPI on a regular basis for 6 to 12 weeks. Regardless, biopsies should be obtained, if possible, during food disimpaction, because important information can be obtained and a biopsy that does not reveal features of EoE in PPI-naive patients may be helpful by suggesting a decreased likelihood of EoE.

Stricture Management and Dilations

Esophageal stricture is the most severe complication of EoE. Symptoms of stricture include dysphagia, delayed transit of food, and recurrent impaction. Recent evidence suggests that long-standing, untreated EoE leads to fibrostenosis.41 Note that not all patients with severe, prolonged esophageal eosinophilia develop strictures. Alternatively, many patients with EoE who have esophageal strictures have developed coping mechanisms to deal with their symptoms, which can mask or further delay diagnosis. For example, patients may chew their food for a prolonged period of time or cut their food into very small pieces. They may also drink large quantities of water during meals in order to ease the passage of food, or they may take longer than an hour to eat a meal. Hence, diagnosis of stricture in EoE may require obtaining a specialized patient history that targets the identification of such behaviors.

EGD is not considered an adequate means of identifying esophageal strictures in EoE. Not only can an esophageal stricture or luminal narrowing be difficult to appreciate by EGD, but esophageal laceration can occur with passage of the scope, because of a small-caliber and/or crepe-paper appearance of the mucosa. An esophagram is helpful in patients with EoE who present with dysphagia or feeding difficulty and may diagnose strictures or narrowing more reliably.16, 42

Esophageal stricture formation is rare in pediatric EoE compared with adults with the diagnosis, with the exact rate of this complication in children unknown.12 Because esophageal narrowing and tissue inflammation have been shown to be reversible in children undergoing treatment of EoE,43 dilation is most commonly recommended for symptomatic relief in patients who do not respond to medical therapy or who have irreversible stenotic lesions. In contrast, in adults with EoE, some physicians use dilation as a primary monotherapy.44 Although this method of therapy may provide symptomatic relief, it is important to recognize that dilation does not treat the underlying esophageal inflammation in EoE and almost always needs to be repeated.

Before 2008, the rate of complications from esophageal dilation in patients with EoE was thought to be higher than in other benign esophageal conditions. For example, perforation rates were reported as high as 5%. However, in recent years larger-scale studies, some of which have included pediatric patients, have shown that the rate of perforation is considerably less than had been previously reported.45 The most recent EoE consensus guidelines report only 3 perforations out of 839 performed dilations.1 However, the guideline investigators also speculate that this decrease in perforations may reflect growing gastroenterologist experience with dilation in EoE.

To date, there are no standard dilation techniques for children and many of the practices are extrapolated from the adult literature. Bougie dilation and balloon pull-through techniques have both been successful in providing symptomatic relief in adults with esophageal stricture.46 Although both dilation approaches are reported to be safe in adults,47, 48 their safety and efficacy have not been formally studied in the pediatric population.

Challenges with Eosinophilic Esophagitis Management

Although established consensus guidelines for EoE diagnosis and management are available,1, 15 there may be variation in interpretation of clinical history and histologic findings because the disease is patchy and many pathologists do not specify the size of a high-power field.17 There is also significant variability in the practice among pediatric and adult providers.49–52 For example, some providers do not recommend a PPI trial before endoscopy,49 complicating the diagnostic distinction between GERD and PPI-REE, which may drastically change the management approach.

Another consideration in clinical management is the timing and interpretation of endoscopic evaluation in the context of a patient’s treatment regimen for allergies, asthma, and other disorders. EoE is often comorbid with other allergic disorders, and reports of anecdotal experience have suggested that patients with allergic rhinitis may have a proximal esophageal eosinophilia that resolves with nasal corticosteroids. Nevertheless, at this time, there is no evidence to suggest any endoscopic or histologic benefit in EoE from nasal or inhaled steroids or antihistamines.

In addition, physicians must also always be aware of concomitant medication use. For example, systemic steroid therapy can induce clinical and pathologic remission of EoE.53 Therefore, unless a patient is being treated primarily for EoE, patients taking systemic corticosteroids should undergo endoscopy at least 4 to 6 weeks after systemic steroid therapy to appropriately assess EoE disease status.

EMERGING METHODS OF DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Although established guidelines exist for EoE histologic diagnosis, there are current limitations of diagnosis and monitoring because EoE is a patchy disease and esophageal eosinophilia can result from other causes.54, 55 In addition, there has been some controversy over the variability in a diagnostic eosinophil count among investigators and pathologists both in eosinophil counts and high-power fields.17 Histologic evaluation may diagnose EoE with 99% specificity, but only 80% sensitivity.17, 56 Additional review of biopsies, particularly those with borderline eosinophil counts, may result in increased sensitivity and more accurate EoE diagnosis.56 Furthermore, unless deep esophageal mucosal biopsies are obtained with jumbo forceps, esophageal fibrosis and remodeling are difficult to detect in early stages before stricture formation. Emerging technologies in EoE include tissue biomarkers and methods, which may help to measure and monitor fibrosis, as well as further optimize disease diagnosis, monitoring, and management. These technological advances use both invasive and noninvasive approaches, and include new endoscopic instruments, such as Endo- FLIP, and use of less invasive tests, such as the cytosponge.

Molecular Analysis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Tissue Samples

Gene expression profiling57 using esophageal biopsies has led to development of a 96-gene panel, which may be available for future use to distinguish patients with active EoE from those in remission as well as from those with GERD, PPI-REE, and healthy controls.58 RNA sequencing has identified transcriptional regulators involved in EoE and associated with the inflammatory milieu.20 These methods have not yet been integrated into current standard of care for EoE, although molecular diagnostic techniques will likely enhance interpretation of esophageal biopsies, as well as EoE disease management in the future.

Endoscopic Ultrasonography

Although EoE is characterized by esophageal epithelial findings, evidence of dysmotility59 and stricture formation in EoE suggest that the disorder extends to deeper layers than are evaluated by endoscopic biopsy, thus warranting further diagnostic methods. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) evaluation of children and adults with EoE has provided further insight into the associated esophageal dysfunction and dysphagia. Expansion of the esophageal wall and individual tissue layers has been shown in children with EoE compared with healthy controls.60 Functional studies performed in coordination with EUS have revealed esophageal longitudinal muscle dysfunction, as opposed to circular muscle function, which is typically detected with esophageal manometry.61 Furthermore, the associated functional impairment improved with treatment.61 Although EUS is not currently part of the EoE guidelines in children or adults, this diagnostic tool may provide further insight into future EoE management regarding fibrosis and esophageal motility.

EndoFLIP

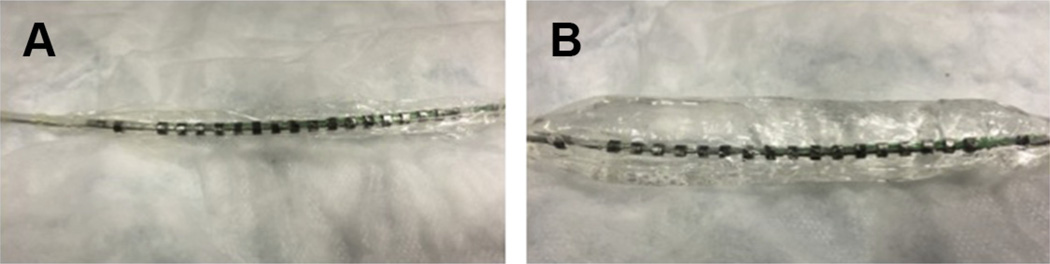

EndoFLIP (endoluminal functional lumen imaging probe) uses high-resolution impedance palimetry to determine the pressure-geometry relationship or distensibility of hollow gastrointestinal organs, including the esophagus. The EndoFLIP catheter has an inflatable bag with pressure sensors (Fig. 4). The balloon is inserted into the esophagus while the patient is anesthetized and inflated with saline under endoscopic guidance. The catheter pressure sensors detect esophageal diameter and distensibility. A recent study using the EndoFLIP has shown decreased distensibility of the esophagus in adult patients with EoE compared with non-EoE controls. The impaired distensibility correlated with increased risk of food impaction and disease severity in the EoE population.62

Fig. 4.

EndoFLIP catheter. (A) EndoFLIP catheter deflated, and (B) inflated.

Manometry

High-resolution manometry in adults with EoE has shown an increase in panesophageal pressurization and peristaltic dysfunction.63 This increase may result because eosinophilic infiltration occurs not only in the epithelium of the EoE esophagus but also throughout the lamina propria and muscularis.64 Feline esophageal smooth muscle strips displayed abrogated muscle contraction in the presence of eosinophil sonicates as well as EoE-associated cytokines, suggesting that inflammation hinders proper muscle function.64 Further studies have correlated duration of disease with abnormal manometry studies65 as well as the presence of fibrostenosis. 66 Although manometric evaluation may be useful to help explain dysphagia in this population, there are limited data to suggest manometry as a marker of disease activity. There is no current literature evaluating the motility of pediatric patients with EoE.

String Test and Cytosponge

The newest methods to evaluate EoE disease activity without endoscopy involve sampling of the esophageal milieu with a string67 or tissue with a sponge.68 The esophageal string test is an adaptation of the Enterotest, formerly used to diagnose gastrointestinal infection. A capsule with an internally coiled string is swallowed while the proximal end of the string is taped to the cheek and left in place for hours, sometimes overnight. The secretions obtained on the string from patients with active EoE have enhanced concentrations of eosinophil-derived proteins compared with inactive and control patients.67

Similarly, the cytosponge is a sponge within a capsule attached to a string. It is swallowed and after 5 minutes the capsule dissolves and the sponge is removed. The sponge is able to sample the epithelium and the tissue collected can be evaluated histologically for eosinophilia.68

Serum Testing

Although there are many serologic findings in the EoE population, none currently distinguish EoE from other atopic conditions. Serum peripheral eosinophilia, immuno-CAP testing, and IgE level do not correlate with active EoE. Larger-scale investigations of individual serum cytokines found no difference between patients with EoE and controls. 69, 70 Levels of eosinophil-derived neurotoxin have been shown to be significantly increased in the serum of patients with active EoE but not in stool samples.70 A specific serum micro-RNA (miRNA) signature pattern including induction of miR-21 and miR-223, and repression of miR-375 has been associated with EoE and is distinct from healthy control patients and those with noneosinophilic forms of esophagitis.71, 72 Furthermore, this signature nearly completely reverts to normal on disease remission. 71, 72 Despite these findings, serum miRNA levels do not always reflect changes in esophageal biopsies73 and further investigation is warranted to determine the clinical and diagnostic significance of miRNA dysregulation in EoE.

SUMMARY

Upper endoscopy with biopsies remains the cornerstone of diagnosis and surveillance in pediatric EoE. In making the diagnosis, it is critical to evaluate for other causes of esophageal eosinophilia, including PPI-REE. Children with known EoE should be considered to be on adequate therapy when there is remission of clinical symptoms and pathologic findings. Although there are many promising less invasive modalities emerging, histopatholgic examination of tissue is currently the only method of monitoring disease activity and fibrosis in pediatric and adult EoE.

KEY POINTS.

Endoscopy is currently the only way to diagnose eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) and monitor disease activity.

Food impaction occurs frequently in undiagnosed or chronic EoE, especially in the adult population, and may result in emergent endoscopic disimpaction.

Stricture dilation in EoE may relieve symptoms of dysphagia but does not attenuate underlying inflammation.

Endoscopic tools are being studied to find additional invasive biomarkers of disease activity.

Less invasive techniques to diagnose and evaluate disease activity are currently being investigated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. e26 [quiz: 21-2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jyonouchi S, Brown-Whitehorn TA, Spergel JM. Association of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders with other atopic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29(1):85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.09.008. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(4):589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.008. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merves J, Muir A, Modayur Chandramouleeswaran P, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(5):397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra A. Mechanism of eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.09.010. viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clayton F, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with IgG4 and not mediated by IgE. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(3):602–609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A, et al. Identification of causative foods in children with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with an elimination diet. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.021. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, et al. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(4):777–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugnanam KK, Collins JT, Smith PK, et al. Dichotomy of food and inhalant allergen sensitization in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2007;62(11):1257–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klinnert MD, Silveira L, Harris R, et al. Health-related quality of life over time in children with eosinophilic esophagitis and their families. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(3):308–316. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen ET, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, et al. Health-care utilization, costs, and the burden of disease related to eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(5):626–632. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(12):1198–1206. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62(4):489–495. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoepfer AM, Panczak R, Zwahlen M, et al. How do gastroenterologists assess overall activity of eosinophilic esophagitis in adult patients? Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(3):402–414. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):679–692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. [quiz-693] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menard-Katcher C, Swerdlow MP, Mehta P, et al. Contribution of esophagram to the evaluation of complicated pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000849. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins MH. Histopathologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis and eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43(2):257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah A, Kagalwalla AF, Gonsalves N, et al. Histopathologic variability in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):716–721. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noti M, Kim BS, Siracusa MC, et al. Exposure to food allergens through inflamed skin promotes intestinal food allergy through the thymic stromal lymphopoietin-basophil axis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1390–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.021. 1399.e1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherrill JD, Kiran KC, Blanchard C, et al. Analysis and expansion of the eosinophilic esophagitis transcriptome by RNA sequencing. Genes Immun. 2014;15(6):361–369. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, et al. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1292–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Rodriguez-Jimenez B, et al. A striking local esophageal cytokine expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1):208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.039. 217.e1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mueller S. Classification of eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22(3):425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pentiuk S, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Dissociation between symptoms and histological severity in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(2):152–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817f0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abu-Sultaneh SM, Durst P, Maynard V, et al. Fluticasone and food allergen elimination reverse sub-epithelial fibrosis in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(1):97–102. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagalwalla AF. Dietary treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. Dig Dis. 2014;32(1–2):114–119. doi: 10.1159/000357086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(9):1097–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helou EF, Simonson J, Arora AS. 3-yr-follow-up of topical corticosteroid treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(9):2194–2199. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teitelbaum JE, Fox VL, Twarog FJ, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children: immunopathological analysis and response to fluticasone propionate. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(5):1216–1225. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora AS, Perrault J, Smyrk TC. Topical corticosteroid treatment of dysphagia due to eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(7):830–835. doi: 10.4065/78.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aceves SS, Bastian JF, Newbury RO, et al. Oral viscous budesonide: a potential new therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2271–2279. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01379.x. [quiz-2280] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, et al. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(2):418–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(5):1381–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1526–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.048. 1537.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hurtado CW, Furuta GT, Kramer RE. Etiology of esophageal food impactions in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52(1):43–46. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181e67072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falk GW. Clinical presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43(2):231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, et al. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(7):795–801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sperry SL, Crockett SD, Miller CB, et al. Esophageal foreign-body impactions: epidemiology, time trends, and the impact of the increasing prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(5):985–991. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alrazzak BA, Al-Subu A, Elitsur Y. Etiology and management of esophageal impaction in children: a review of 11 years. Avicenna J Med. 2013;3(2):33–36. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.114113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1230–1236. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gentile N, Katzka D, Ravi K, et al. Oesophageal narrowing is common and frequently under-appreciated at endoscopy in patients with oesophageal eosinophilia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(11–12):1333–1340. doi: 10.1111/apt.12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Chen D, et al. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy. 2010;65(1):109–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipka S, Keshishian J, Boyce HW, et al. The natural history of steroid-naive eosinophilic esophagitis in adults treated with endoscopic dilation and proton pump inhibitor therapy over a mean duration of nearly 14 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(4):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dellon ES, Cullen NR, Madanick RD, et al. Outcomes of a combined antegrade and retrograde approach for dilatation of radiation-induced esophageal strictures (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(7):1122–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madanick RD, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. A novel balloon pull-through technique for esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(1):138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schoepfer AM, Gonsalves N, Bussmann C, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: effectiveness, safety, and impact on the underlying inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(5):1062–1070. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirano I. Dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: to do or not to do? Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(4):713–714. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peery AF, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Practice patterns for the evaluation and treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(11–12):1373–1382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, et al. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52(3):300–306. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181eb5a9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Molina-Infante J, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults: results from a Spanish registry of clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(7):562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dellon ES, Aderoju A, Woosley JT, et al. Variability in diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2300–2313. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liacouras CA, Wenner WJ, Brown K, et al. Primary eosinophilic esophagitis in children: successful treatment with oral corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26(4):380–385. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodrigo S, Abboud G, Oh D, et al. High intraepithelial eosinophil counts in esophageal squamous epithelium are not specific for eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(2):435–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, et al. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(3):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stucke EM, Clarridge KE, Collins MH, et al. The value of an additional review for eosinophil quantification in esophageal biopsies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61(1):65–68. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):536–547. doi: 10.1172/JCI26679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wen T, Stucke EM, Grotjan TM, et al. Molecular diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis by gene expression profiling. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1289–1299. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mavi P, Rajavelu P, Rayapudi M, et al. Esophageal functional impairments in experimental eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(11):G1347–G1355. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00013.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fox VL, Nurko S, Teitelbaum JE, et al. High-resolution EUS in children with eosinophilic “allergic” esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(1):30–36. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Korsapati H, Babaei A, Bhargava V, et al. Dysfunction of the longitudinal muscles of the oesophagus in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2009;58(8):1056–1062. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.168146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicodeme F, Hirano I, Chen J, et al. Esophageal distensibility as a measure of disease severity in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(9):1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.020. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martin Martin L, Santander C, Lopez Martin MC, et al. Esophageal motor abnormalities in eosinophilic esophagitis identified by high-resolution manometry. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(9):1447–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rieder F, Nonevski I, Ma J, et al. T-helper 2 cytokines, transforming growth factor beta1, and eosinophil products induce fibrogenesis and alter muscle motility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1266–1277. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.051. e1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Rhijn BD, Oors JM, Smout AJ, et al. Prevalence of esophageal motility abnormalities increases with longer disease duration in adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26(9):1349–1355. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Colizzo JM, Clayton SB, Richter JE. Intrabolus pressure on high-resolution manometry distinguishes fibrostenotic and inflammatory phenotypes of eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis esophagus. 2015 doi: 10.1111/dote.12360. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Furuta GT, Kagalwalla AF, Lee JJ, et al. The oesophageal string test: a novel, minimally invasive method measures mucosal inflammation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2013;62(10):1395–1405. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katzka DA, Geno DM, Ravi A, et al. Accuracy, safety, and tolerability of tissue collection by cytosponge vs endoscopy for evaluation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.026. e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dellon ES, Rusin S, Gebhart JH, et al. Utility of a noninvasive serum biomarker panel for diagnosis and monitoring of eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(6):821–827. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Subbarao G, Rosenman MB, Ohnuki L, et al. Exploring potential noninvasive biomarkers in eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53(6):651–658. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318228cee6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sherrill JD, Rothenberg ME. Genetic and epigenetic underpinnings of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43(2):269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lu TX, Sherrill JD, Wen T, et al. MicroRNA signature in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, reversibility with glucocorticoids, and assessment as disease biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(4):1064–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.060. e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zahm AM, Menard-Katcher C, Benitez AJ, et al. Pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with changes in esophageal microRNAs. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307(8):G803–G812. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00121.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]