Abstract

The protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei causes the fatal illness human African trypanosomiasis (HAT). Standard of care medications currently used to treat HAT have severe limitations, and there is a need to find new chemical entities that are active against infections of T. brucei. Following a “drug repurposing” approach, we tested anti-trypanosomal effects of carbazole-derived compounds called “Curaxins”. In vitro screening of 26 compounds revealed 22 with nanomolar potency against axenically cultured bloodstream trypanosomes. In a murine model of HAT, oral administration of compound 1 cured the disease. These studies established 1 as a lead for development of drugs against HAT. Pharmacological time-course studies revealed the primary effect of 1 to be concurrent inhibition of mitosis coupled with aberrant licensing of S-phase entry. Consequently, polyploid trypanosomes containing 8C equivalent of DNA per nucleus and three or four kinetoplasts were produced. These effects of 1 on the trypanosome are reminiscent of “mitotic slippage” or endoreplication observed in some other eukaryotes.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) is a disease endemic to regions of sub-Saharan Africa, and is caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei. Nearly 70 million people are at risk of contracting HAT1. Drug therapy is necessary to cure this otherwise fatal infectious disease2.

The five drugs currently registered to treat HAT are suramin, pentamidine, melarsoprol, eflornithine and nifurtimox. Except for nifurtimox (administered orally, but only in combination with the injectable drug eflornithine), none are orally bioavailable. Thus, an entirely orally bioavailable treatment regimen does not exist for treatment of HAT. Other problems relating to safety have led to renewed calls for safe and orally bioavailable anti-HAT drugs, even as clinical trials for two leads (Fexinidazole3 and SCYX-71584) are ongoing (reviewed in refs 1, 5 and 6).

There are several strategies for discovering drugs against neglected human diseases such as HAT7,8,9,10. In this study we utilize a “drug repurposing” approach7 in which drugs developed for one indication are tested for efficacy against a different disease. Chemical scaffolds of drugs that are active against parasites in vitro and in a mouse model of HAT could be subsequently optimized through medicinal chemistry efforts to create novel anti-trypanosome compounds10,11.

Carbazole scaffolds are found in some marketed drugs or are “hits” in development for treatment of chronic disease. For example, carprofen, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic is a carbazole derivative12. N-alkyl carbazoles as well as aminopropyl-carbazoles are under investigation as lead drugs to treat Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases13,14,15,16. As part of a drug discovery initiative, Cleveland BioLabs, Inc. synthesized a class of carbazole derivatives termed “Curaxins”. Some Curaxins can intercalate into DNA, though they are non-genotoxic in that they do not induce DNA damage17 and influence activity of the “facilitates chromatin transcription” (FACT) complex in some human cancer cells17,18.

We tested this class of compounds against T. brucei for several reasons. First, several of them were orally bioavailable and had excellent in vivo toxicology properties17. Moreover, CBL0137 (1, Fig. 1a) has completed phase I clinical trials for treatment of advanced solid tumors and lymphomas19. Finally, methods for synthesis of this family of compounds were available, enabling production of new analogs based on evolving phenotypic structure-activity relationship data20.

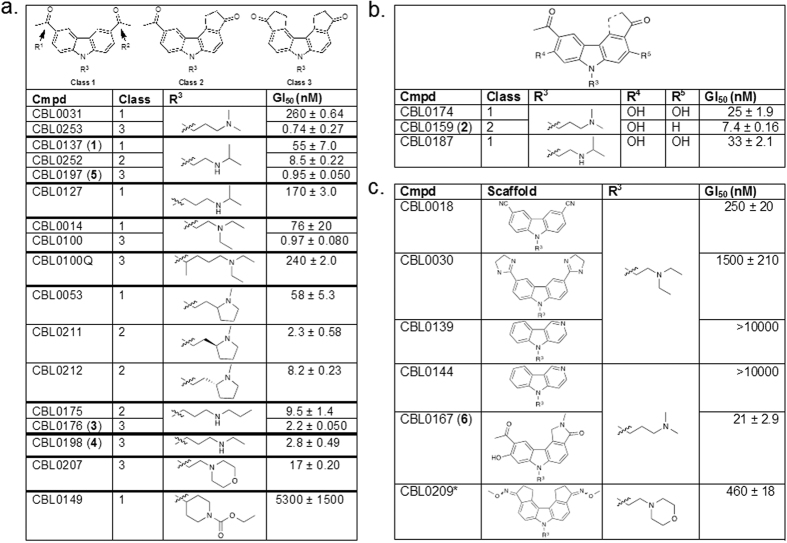

Figure 1. Inhibition of T. brucei proliferation: Exploratory Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR).

T. brucei (4 × 103 cells/mL) in 24-well or 96-well plates were incubated with DMSO or compound (various concentrations) for 48 h. The amount of drug that inhibits trypanosome proliferation 50% (GI50) was determined for each compound. Mean GI50 were determined from two independent experiments (totaling four separate biological replicates) within +/− standard deviation. (a) SAR of Class 1 (R1 and R2 = acetyl groups), Class 2 (R1 = acetyl group, R2 = cyclopentanone), and Class 3 (R1 and R2 = cyclopentanone). (b) Class 1, 2 or 3 structures with hydroxyls at R4 and/or R5. (c) Other compounds not qualified as Class 1, 2 or 3. *For CBL0209 we do not know which E/Z isomers were tested.

We report here that many representatives of this class of compounds inhibited proliferation of bloodstream T. brucei in vitro at nanomolar concentrations. CBL0137 (1), CBL0159 (2) and CBL0176 (3) were tested in a mouse model of HAT. Administered orally, they increased survival of infected mice compared to control untreated animals. Compound 1 cured 100% of infected mice, qualifying it as a lead drug worthy of pre-clinical evaluation studies according to guidelines on tropical diseases set forth by the World Health Organization21. In “mode of action” studies, we found that 1 inhibits mitosis and re-licenses entry into S-phase of the cell division cycle, leading to emergence of polyploid T. brucei.

Materials and Methods

Drugs

Samples of compounds (>95% pure) including CBL0137 (lot #10-106-88-30) were provided by Cleveland BioLabs, Inc. (Buffalo, NY). For in vitro studies, 10 mM stock solutions of the compounds were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). For oral gavage of mice, the compounds were formulated in 0.2% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC).

Cell culture

Bloodstream form (BSF) Trypanosoma brucei was maintained at densities below 106 cells/mL at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in HMI-9 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals; Atlanta, GA), 10% SERUM PLUSTM (Sigma; St. Louis, MO), and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic Solution (Corning cellgro®; Corning NY)22. T. brucei brucei RUMP52823, and T. brucei rhodesiense KETRI 248224 (a gift from Stephen Hajduk, University of Georgia), were used for these studies. All trypanosome experiments were performed using T. b. brucei unless otherwise specified.

Human HeLa cells were grown in 75 cm2 vented cap culture flasks (Corning) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Corning cellgro®) containing 10% FBS, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic Solution25. Cultures were maintained at up to 80% confluency.

Trypanosome and HeLa cell-based proliferation inhibition assays

T. brucei and HeLa cells were cultured as described9 with modifications.

T. brucei

T. brucei (brucei or rhodesiense) were seeded at 4 × 103 cells/mL in 24-well plates (0.5 or 1 mL of culture per well). Cells were incubated for 48 h with 1 or 2 μL of DMSO (vehicle control) or compound in DMSO. Compounds were initially tested at 10 nM, 100 nM or 1 μM, to define a range where cell density responded to drug concentrations. Then, at least five drug concentrations26 covering this range was used for subsequent assays. Each concentration was tested in duplicate. Cell density was determined with a Neubauer Bright-Line hemocytometer (Sigma) after 48 h. Cells were counted only if they were motile. Mean cell counts were plotted against compound concentration and the GI50 (compound concentration that inhibits T. brucei proliferation by 50%) was determined by linear interpolation using Excel for Mac 2011 (Microsoft)27. Final mean GI50 values were calculated based on two independent experiments, each with at least five data points performed in duplicate.

HeLa cells

HeLa cells were seeded to 1 × 105 cells/mL in 24-well plates (1 mL of culture per well) and incubated drug-free for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. DMSO or stock inhibitor concentration (5 μL) was added to obtain the specified final concentrations. Cells were incubated for 24 h28,29 at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Next, cells were trypsinized and cell density was determined with a Neubauer Bright-line hemocytometer as described9. GI50 for each compound was calculated by plotting data for the cell counts in Excel as described for T. brucei above. Data were obtained from two independent experiments, four separate biological replicates.

High throughput trypanosome proliferation inhibition assay

T. brucei were seeded at 4 × 103 cells/mL and dispensed into wells of a 384-well black plate (Greiner; Frickenhausen, Germany). Wells in two columns per plate were filled with 50 μL of HMI-9 medium using a Multidrop Combi (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA) to serve as a background control. Fifty microliters of trypanosome suspension was added to separate columns using a Multidrop Combi. Lastly, an additional 50 μL of cell resuspension was added to only the top row of wells that contained cells (row A, labeled by Greiner), using an Xplorer multichannel pipette (Eppendorf; Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany) bringing final volumes of cell-containing wells in the top row to 100 μL.

Prior to their addition to assay plates, DMSO or compounds in DMSO were diluted 1:4 (v/v) with HMI-9 medium in 0.2 mL tubes (MidSci; St. Louis, MO). A microliter of DMSO (25%) or diluted drug was added to wells containing cells of the top row using an Xplorer multichannel pipette. Each concentration was tested in duplicate. Cells and DMSO/drug were mixed and serially diluted 1:2 down the rows of the plate.

Plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and loaded into a Fluoroskan Ascent Microplate Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific). Cells were lysed by addition of 15 μL of SYBR Green I (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) in lysis solution30 (5X SYBR Green I, 30 mM Tris pH 7.5, 7.5 mM EDTA, 0.012% saponin and 0.12% Triton X-100) to each well. Plates were agitated at 1200 rpm for 45 s, incubated in the dark for 1 h at room temperature, and fluorescence was detected (ex: 485 nm, em: 538 nm) using 100 ms integration time. Data collected was exported to Excel from Ascent Software (Thermo Scientific). Base-line corrected non-linear regression graphs were generated and GI50 values determined using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software; La Jolla, CA). Final mean GI50 values were calculated based on four separate biological replicates.

Infection of mice with T. brucei brucei

Cultured T. brucei were pelleted and resuspended in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% glucose at 1 × 105 cells/mL. Female Swiss-Webster mice (8–10 weeks old, 20–25 g, n = 4 per group) (Harlan; Indianapolis, IN) were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 104 bloodstream trypanosomes in 100 μL of PBS using 26G needles. To avoid damage to T. brucei cells, mechanical stress during administration was minimized by avoiding repeated pulling and pushing movements of cell resuspension through the syringe needle. Starting 48 h post-infection, and every 1–8 days thereafter, parasitemia was monitored by collecting 3 μL of blood from the tail vein of mice. Blood samples were supplemented with 21 μL of RBC Lysis Solution (Qiagen; Valencia, CA) and incubated at room temperature for 15–45 min. prior to observing for parasites using a Neubauer Bright-line hemocytometer. Mice with parasitemia greater than 2 × 108 trypanosomes/mL were euthanized. Mice were considered cured if they lived more than 30 days after experimental treatment ended and had no detectable parasites in the blood at that time31,32. To compare animal survival in treatment and vehicle control groups, Student’s t-test was performed in Excel to generate p-values. All animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Georgia. All experimental protocols involving animals were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines of the IACUC at the University of Georgia.

Drug administration and determination of parasitemia in mice

Formulated compounds or vehicle control (0.2% HPMC) were administered by oral gavage starting 24 h after mouse infection with T. brucei33,34. Animals were weighed before each compound administration, and dose volume was adjusted based on body weight (10 mL/kg) to deliver accurate doses of test compounds. The treatment was ceased for animals when normalized body weight (NBW) loss exceeded 20%, and resumed after NBW recovery above 90%. Compounds 1–3 were administered orally once per day of treatment 24 h post-infection as follows. 1: 30 mg/kg or 40 mg/kg, treatment regimen of “4 days on/2 days off” for a total of 14 doses; 2: 20 mg/kg (days 2–5), 10 mg/kg (day 7), 5 mg/kg (days 8–9), no drug (day 6, days 10–13); 3: 25 mg/kg (days 2–5), 12.5 mg/kg (day 7), 6.25 mg/kg (days 8–10), no drug (day 6, days 11–13). Scheduled euthanasia by CO2 overdose followed by incision to form a bilateral pneumothorax was conducted on mice considered cured 30 days after the end of experimental treatment (see previous section). Mice with parasitemia greater than 2 × 108 trypanosomes/mL or NBW losses ≥30% were subjected to unscheduled euthanasia.

Effects of ethidium bromide and compound 1 on kinetoplast duplication and nucleus mitosis

Thirty-hour compound 1 treatment of trypanosomes

T. brucei were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/mL in 175 cm2 vented cap culture flasks containing 100 mL of HMI-9 medium and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 30 h with 1 (200 nM), ethidium bromide (EtBr, 200 nM), sterile deionized H2O or DMSO (0.1%). At stated times trypanosome density was determined using a Z2 Coulter Counter (Beckman). A 10 mL aliquot of cell culture per sample (1 × 106–2 × 107 cells total) was collected every 6 h and analyzed using fluorescence microscopy as described below. At the same time-points a 5 mL aliquot (5 × 105–1 × 107 cells total) was collected and analyzed by flow cytometry as described below. All data reported were obtained from three independent experiments.

Fluorescence microscopy

HMI-9 medium (5–10 mL) containing 1 × 105–2 × 106 cells/mL of T. brucei was centrifuged (5 min, 3000 × g at room temperature) to pellet the cells. After supernatant removal cells were resuspended in 1 mL of PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde (Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA) and incubated for either 1 min at room temperature or up to two weeks at 4 °C. Fixed cells were adhered to poly-L-lysine coated coverslips for 15 min at room temperature. Coverslips were washed with approximately 0.1–1 mL of PBS, air dried, then mounted on 2 μL of DAPI (1.5 μM) in Vectashield (Vector Labs; Burlingame, CA). For quantitation, 150 cells per sample were counted for each independent experiment using an EVOS® FL inverted fluorescence microscope (Life Technologies; Grand Island, NY). Images for figures were captured on an Applied Precision DeltaVision microscope system (GE Healthcare; Issaquah, WA) using an Olympus IX-71 inverted microscope (Olympus; Center Valley, PA) at 60X, ex: 435 nm, em: 448 nm. To compare effects on organelle DNA duplication by drug treatment and vehicle control groups, Student’s t-test was performed in Excel to generate p-values.

Flow cytometry

T. brucei (between 5 × 105 cells to 1 × 107 cells) in 5 mL of culture medium were centrifuged (3 min, 3000 × g at room temperature) to pellet cells and washed once with 1 mL of PBS containing 10 mM glucose. Cells were fixed in 1 mL of 70% methanol supplemented by PBS at 4 °C for up to two weeks, centrifuged (3 min, 2000 × g at room temperature), and resuspended at 5 × 105 cells/mL in 1X PBS. RNase A and propidium iodide (PI) were added to each sample to final concentrations of 500 μg/mL and 7.5 μM, respectively, and the suspension was protected from light during incubation for 1 h at 37 °C35. Samples were placed on ice for 15 min and data was immediately collected on a CyAn ADP Analyzer (Beckman Coulter; Hialeah, FL). During analysis with FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC; Ashland, OR), trypanosomes were gated from background debris by plotting “events” as forward scatter vs. side scatter (both on the logarithmic scale). Single trypanosomes were gated for cell cycle analysis from cells stuck together (“doublets”) by plotting trypanosome events as PI fluorescence vs. pulse width. Distribution of trypanosomes into groups containing different amounts of chromosomal DNA was performed using Watson-Pragmatic algorithm in FlowJo. DNA distribution values from independent experiments were averaged with error bars generated and graphed in Excel. To compare effects of drug treatment on DNA content of experimental and vehicle control groups, Student’s t-test was performed in Excel to generate p-values.

“Delayed killing” effects after 6-h exposure of cells to compound 1

T. brucei cells

T. brucei were seeded at 5 × 105 cells/mL in 25 cm2 vented cap culture flasks containing 5 mL of HMI-9 medium and incubated 6 h with 1 (1 μM) or DMSO (0.1%). Cells were centrifuged (3000 × g, 5 min, room temperature), washed twice with HMI-9 medium and resuspended at 1 × 105 cells/mL in 5 mL of HMI-9 medium. Trypanosomes were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 48 h. Cell density was determined with a Neubauer Bright-line hemocytometer as described for cell proliferation assays. Data were obtained from two independent experiments, four separate biological replicates.

HeLa cells

HeLa cells were seeded to 1 × 105 cells/mL in 24-well plates (1 mL of culture per well) and incubated drug-free for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Next, 1 (1 μM) or DMSO (0.1%) was added and cells were treated for 6 h. Cells were washed, trypsinized, and resuspended in equivalent volumes of HMI-9 medium9. Cell density was determined using a Neubauer Bright-line hemocytometer as described in the cell-based proliferation assays. Samples were resuspended in HMI-9 medium to 5 × 104 cells/mL and incubated for 48 h. Cells were counted by hemocytometer, and resuspended to 5 × 104 cells/mL every 48 h for 8 days (192 h) post-treatment. Data were obtained from two independent experiments, four separate biological replicates.

Results

Effect of compounds on trypanosome proliferation: Preliminary structure-activity relationship (SAR)

Twenty-six compounds were screened for their effects on trypanosome proliferation in vitro, by culturing bloodstream T. brucei in different concentrations of each compound. Test compound concentrations causing 50% inhibition of trypanosome proliferation (GI50) were calculated (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). Compounds with GI50 less than 100 nM were classified as “hits”36.

Most compounds were categorized into one of three classes according to the R1 and R2 substituents on the carbazole scaffold (Fig. 1a,b). The most potent inhibitors belonged to Class 3, containing two cyclopentanone rings fused with the carbazole. Most of these inhibitors displayed a GI50 between 0.7–3 nM. Class 2 compounds (with one fused cyclopentanone ring and one acetyl group) had GI50 between 2–10 nM. Class 1 compounds (diacetyl-substituted on the carbazole) had GI50 between 25–300 nM. We could hypothesize a few reasons why this conformational restraint may be relevant. First, this ring restraint could reinforce presentation of the hydrogen bond acceptor carbonyl(s) in a vector that made more favorable interactions with its target(s) of action. Second, the enhanced planarity compared to the acyclic acetyl groups could enhance DNA intercalation. Lastly, we do not rule out a possibility that this structural feature affects other properties that contributed to the potency of Class 3 inhibitors against the parasite. Work is ongoing to test these hypotheses.

Other compounds that did not cleanly fit into the classification system above were tested (Fig. 1c). These compounds all presented H-bond acceptor moieties that could potentially mimic the cyclopentanone carbonyl oxygen, however only one, CBL0167 (6), had appreciable activity with GI50 less than 25 nM (Fig. 1c).

With the exception of CBL0149 (Fig. 1a), the N-linked side chain of each compound tested contained either a basic secondary or tertiary amine. Within the Class 1 compounds, increasing chain length and steric bulk around the amine generally reduced potency. For example, extension of the chain from two to three carbons (1 vs. CBL0127, Fig. 1a) resulted in a 3-fold reduction in potency. In another example, increasing the steric bulk on the linker (CBL0100Q versus CBL0100, Fig. 1a) led to a nearly 250-fold potency loss. Lastly, we noted that hydroxylation of the carbazole core was tolerated in three examples (such as compound 2, Fig. 1b). This initial SAR was instructive with regards to the first round of medicinal chemistry optimization, which will be reported in due course.

Selection of compounds for testing in a mouse model of HAT

To explore anti-trypanosomal effects of the compounds in mice, we selected representatives of each class as defined in Fig. 1. Compound 1 was the best Class 1 candidate to test in vivo because it is well-tolerated in mice following oral administration17, and it had a low GI50 of 55 nM against T. brucei (Fig. 1a). Compounds 2 (Class 2) and 3 (Class 3) were chosen because they were also orally bioavailable (Cleveland BioLabs, unpublished data) and they had low GI50’s of 7.4 nM and 2.2 nM respectively. Furthermore, compounds 1–3 were potent against the human-infective subspecies T. brucei rhodesiense (Table 1).

Table 1. Selectivity Index of hits.

| Cmpd | Growth inhibition (GI50) ± SD (nM) | Selectivity Index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. b. rhodesiense | T. b. brucei | HeLa | HL GI50/Tbb GI50 | |

| 1 | 58 ± 3 | 55 ± 7 | 2100 ± 50 | 38 |

| 2 | 13 ± 3 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 580 ± 100 | 78 |

| 3 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 520 ± 40 | 236 |

Proliferation inhibition of compounds against T. b. brucei, T. b. rhodesiense and human HeLa (HL) cells. T. brucei (4 × 103 cells/mL) in 24-well plates were incubated with DMSO (0.1% vol/vol) or compound (various concentrations) for 48 h. The amount of drug that inhibits trypanosome proliferation 50% (GI50) was determined for each compound. Mean GI50 ± standard deviation was determined from two independent experiments, four separate biological replicates.

Prior to performing drug efficacy studies in a mouse model of HAT, we sought to identify overtly toxic compounds, by determining the GI50 of compounds 1–3 against HeLa cells in vitro (Table 1). The selectivity index (SI) for each compound was calculated as a ratio between HeLa and T. brucei GI50 values. Because 1 is well-tolerated in mice17, it’s SI (38-fold) was used as a threshold for compound selection. Both 2 and 3 had SI values greater than that of 1 (SI = 78 and 236-fold, respectively), indicating less general toxicity by these criteria. Therefore, 1 (Class 1), 2 (Class 2) and 3 (Class 3) were selected for testing in a mouse model of HAT.

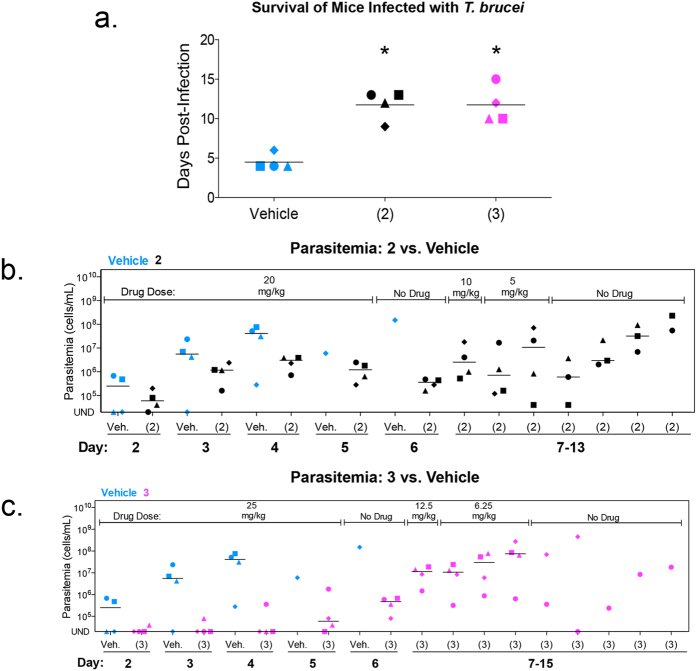

Compound 2 and Compound 3 extend life of mice infected with T. brucei

Following infection with trypanosomes, mice from the vehicle (i.e., untreated) control group survived 5 days on average. Mice treated orally with 2 or 3 had a 2-fold increase in average survival (Fig. 2a). From days two to five a full dose (at the repeated maximum tolerated dose) of either 2 or 3 was orally administered to mice (20 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg respectively). At day six, both compounds reduced parasitemia 100-fold (Fig. 2b,c). However, weight loss exceeding 10% of normal body weight (NBW) was observed in both treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. S2b,c). As a result, over the next several days, doses of both compounds were reduced to limit weight loss. After treatment with 2 and 3 ended (day 10), parasitemia rose and all mice were euthanized for humane reasons because of high parasitemia (>2 × 108 cells/mL) (Fig. 2b,c).

Figure 2. Compounds 2 and 3 reduce trypanosome proliferation in mice.

Mice (n = 4 per group) were infected intraperitoneally with 1 × 104 bloodstream T. brucei. Compound 2, 3 and vehicle were administered orally as indicated in graphs. Doses administered of compound 2: 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg. Doses administered of compound 3: 6.25 mg/kg, 12.5 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg (a) Mean survival of vehicle and compound treated mice. Horizontal lines indicate mean survival (days). Student’s t-test was used to compare survival of vehicle to drug-treated mice. *P < 0.0007. (b,c) Parasitemia of 2 (b) or 3 (c) treated mice compared to vehicle. Individual mice are represented by different symbol shapes. Horizontal lines indicate median parasitemia.

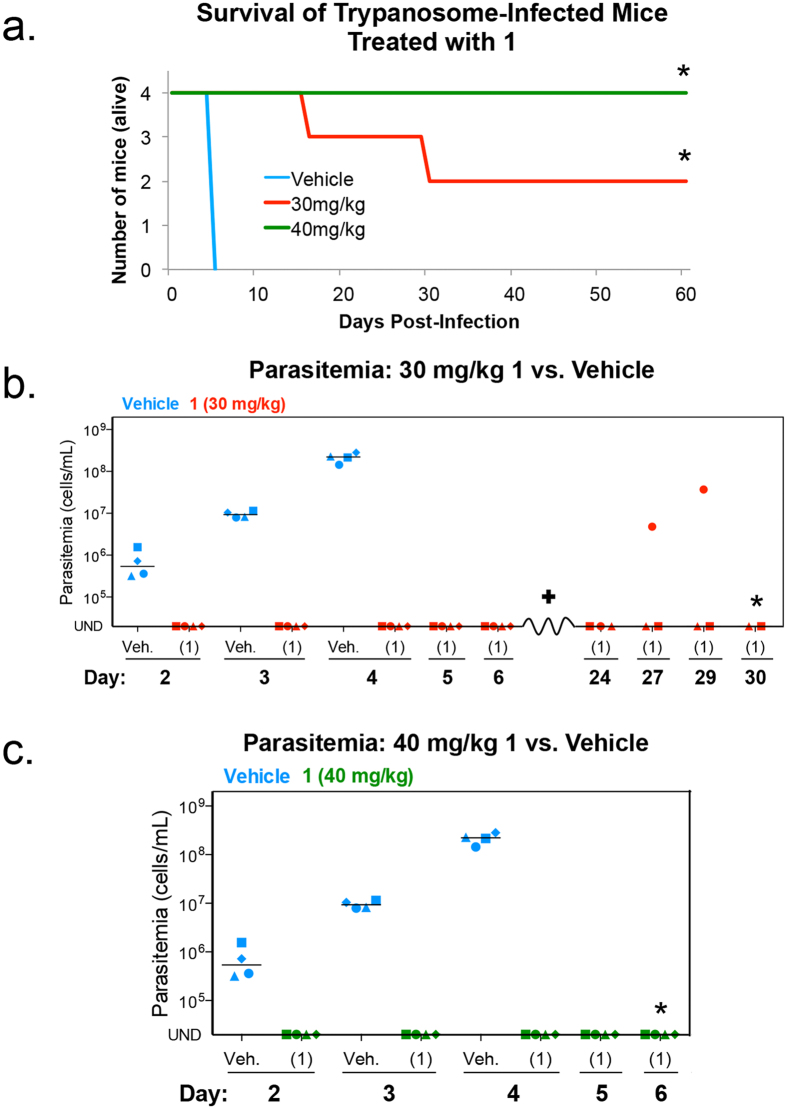

Compound 1 cures T. brucei infection in a mouse model of HAT

Compound 1 was administered to T. brucei-infected mice once per day of treatment (4-on, 2-off) at 30 mg/kg or 40 mg/kg for a total of 14 doses. Little or no weight loss was observed during treatment with 1 (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Vehicle control mice were euthanized for humane reasons by day five because their parasitemia was greater than the 2 × 108 parasites/mL threshold. All mice treated with 1 were alive on day five. A 30 mg/kg dose of 1 cured 50% of trypanosome-infected mice. Following administration of 40 mg/kg, 100% of trypanosome-infected mice were cured of infection (Fig. 3a). Trypanosomes were not observed in peripheral blood of infected mice at either dose level (Fig. 3b,c). Of the two mice that died during the 30 mg/kg treatment, one had no parasitemia and may have died of other causes, whereas the second mouse died following recrudescence observed on day 27 post-infection (Fig. 3b). Overall, this data demonstrated efficacy of 1 in a mouse model of HAT, and established 1 as a lead for T. brucei drug development.

Figure 3. Compound 1 cures T. b. brucei infection in a mouse model of HAT.

Mice (n = 4 per group) were infected intraperitoneally with 1 × 104 bloodstream T. brucei. Compound 1 (30 mg/kg or 40 mg/kg) and vehicle were administered orally once per day of treatment for a total of 14 doses. (a) Number of mice alive post-infection. *All remaining mice were cured of trypanosome infection. (b,c) Parasitemia in mice dosed with vehicle or 30 mg/kg of compound 1 (b) or 40 mg/kg of compound 1 (c). Individual mice are represented by different symbol shapes. Horizontal lines indicate median parasitemia. UND = parasitemia undetectable. Mouse (♦) died on day 16 post-infection, no parasitemia observed prior to death (data not presented). *All remaining mice were cured of trypanosome infection.

Compound 1 affects DNA replication and mitosis

Following discovery of 1 as a lead, we explored that drug’s mode of action by examining its effect on trypanosome cell division. Trypanosomes have chromosomal DNA in the nucleus, and their mitochondrial DNA (kinetoplast DNA (kDNA)) is found in a nucleoid termed the kinetoplast within the mitochondrion. Because compound 1 binds DNA in HeLa cells17 we compared its effects on trypanosome biology to that of ethidium bromide (EtBr), a well-known DNA binding agent that is also anti-trypanosomal37.

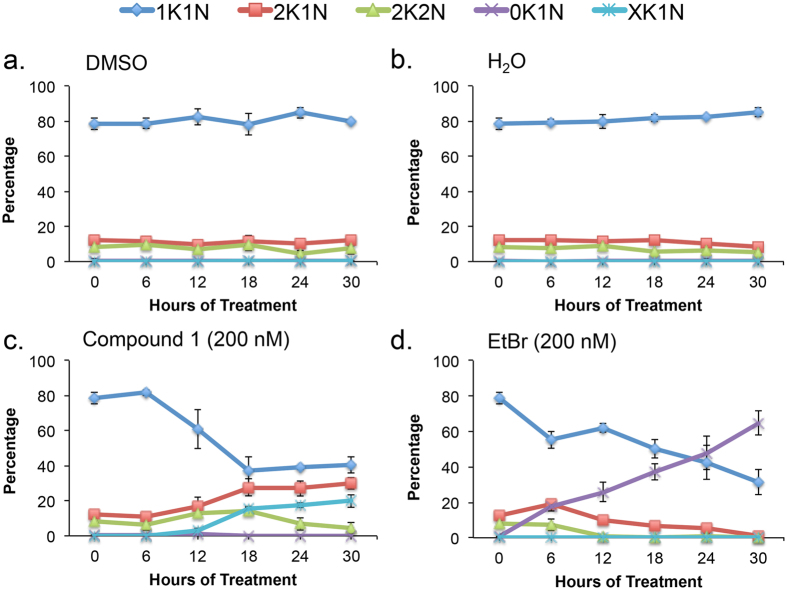

A 30 h time-course of ethidium bromide (EtBr, 200 nM) and 1 (200 nM) treatment was performed with their appropriate vehicle controls under conditions reported to cause dyskinetoplastic formation during EtBr treatment37. Cell density and effects on DNA “karyotype” (i.e., number of nuclei and kinetoplasts per cells) and DNA content were determined from samples collected every 6 h (Figs 4, 5, 6 and 7, Supplementary Figs S4–S8). Both compounds blocked trypanosome proliferation, with only 1.5-fold and 2.5-fold increases in cell density during 30 h treatment with 1 or ethidium bromide (Supplementary Fig. S4). Generally, effects on DNA karyotype/content by either drug reached maximum effect by 24 h (Figs 4 and 6). Therefore, representative microscopy images presented were taken only from trypanosomes obtained at this time-point (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S6).

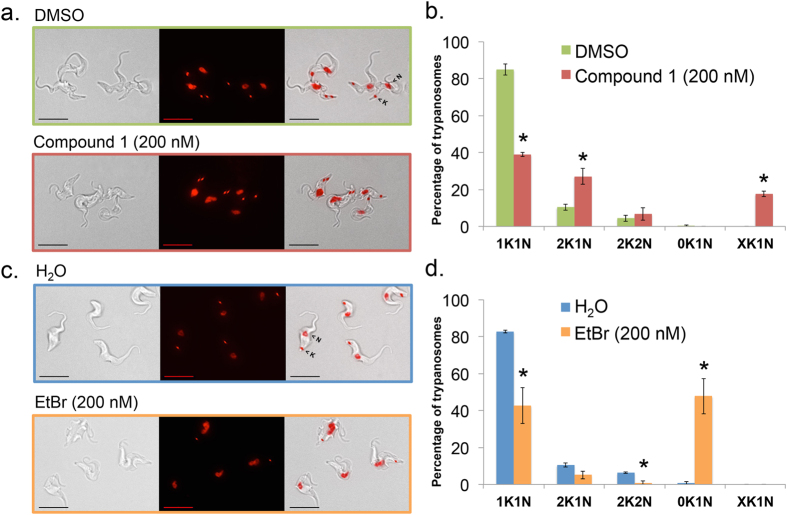

Figure 4. Summary of effects of compound 1 and ethidium bromide on trypanosome nucleus and kinetoplast copy number.

Results summarized from Supplementary Fig. S5. (a) DMSO-treated, (b) H2O-treated, (c) 1-treated, (d) ethidium bromide-treated. Mean percentage of cells +/− standard deviation were determined from three independent experiments.

Figure 5. Effects of 24 h compound 1 treatment on trypanosome nucleus and kinetoplast copy number.

T. brucei (1 × 105 cells/mL) were treated with 1 (200 nM), ethidium bromide (200 nM), H2O, or DMSO (0.1% vol/vol) for 24 h as part of a 30 h time-course in HMI-9 medium (Supplementary Fig. S5). Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS) and DNA was stained with DAPI (1.5 μM). (a,c) Representative images of 24 h treated cells. Panels = Left: DIC (differential interference contrast), middle: DAPI (red), right: Merge. Bar = 10 μm. (b,d) Nuclei (N) and kinetoplasts (K) were counted from 150 cells for each sample. 1K1N, trypanosomes with one kinetoplast/one nucleus; 2K1N, trypanosomes with two kinetoplasts/one nucleus; 2K2N, trypanosomes with two kinetoplasts/two nuclei; 0K1N, trypanosomes without visible kinetoplasts/one nucleus; XK1N, trypanosomes with more than two kinetoplasts/one nucleus. Mean percentage of cells +/− standard deviation were determined from three independent experiments. Student’s t-test was used to compare organelle copy number distribution of vehicle (DMSO or H2O) to drug-treated trypanosomes. *P < 0.05, determined by Student’s t-test.

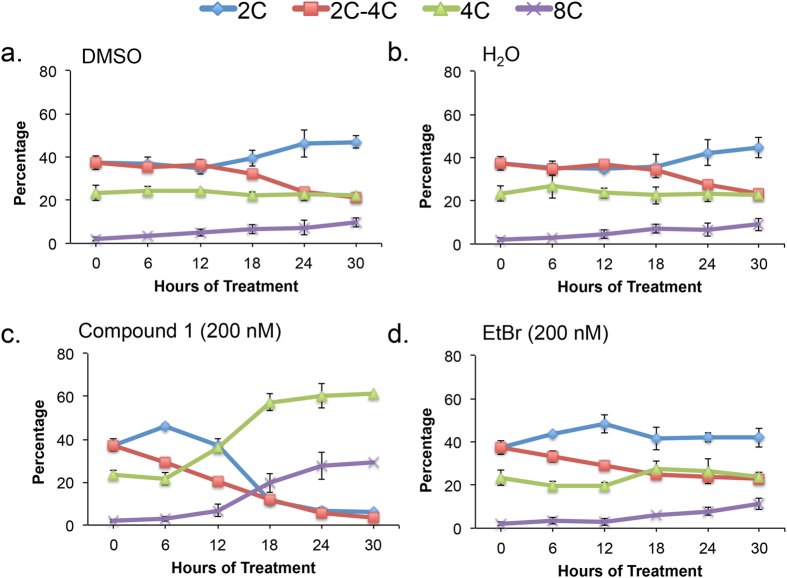

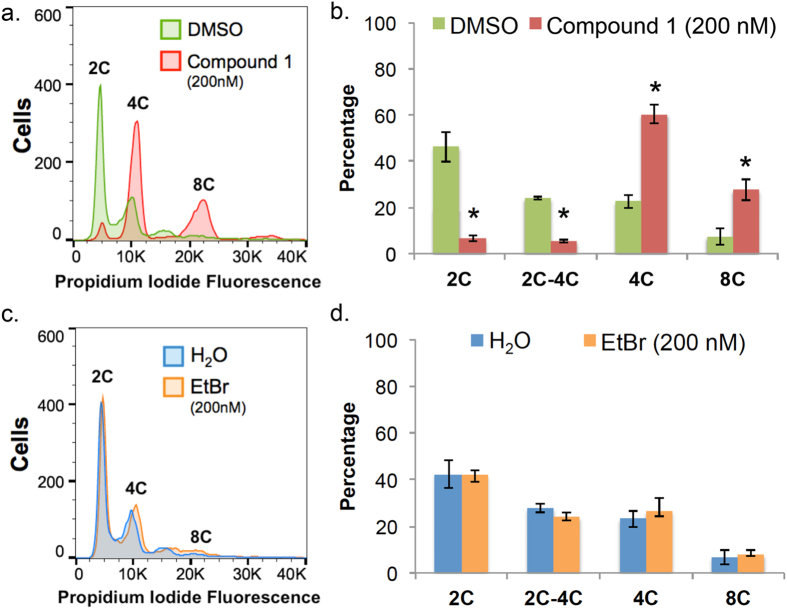

Figure 6. Summary of effects of compound 1 and ethidium bromide on nuclear DNA content.

Results summarized from Supplementary Figs S7 and S8. (a) DMSO-treated, (b) H2O-treated, (c) 1-treated, (d) ethidium bromide-treated. Mean percentage of cells +/− standard deviation were determined from three independent experiments.

Figure 7. Effects of 24 h compound 1 treatment on nuclear DNA content.

T. brucei (105 cells/mL) were treated with 1 (200 nM), ethidium bromide (200 nM), H2O, or DMSO (0.1% vol/vol) for 24 h as part of a 30 h time-course in HMI-9 medium (Supplementary Figs S7 and S8). Cells were fixed with PBS containing 70% methanol, treated with RNase A (500 μg/mL) and DNA was stained with propidium iodide (7.5 μM). (a,c) Histograms of DNA content per cell. 10,000 trypanosomes were analyzed per sample. Chromosomal content (e.g. “2C”) is indicated for each peak. (b,d) Proportion of cells with DNA content from 2C–8C. Mean percentage of cells +/− standard deviation were determined from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, determined by Student’s t-test comparing DNA content of vehicle (DMSO or H2O) to drug-treated trypanosomes.

Ethidium bromide (200 nM) produced dyskinetoplastic trypanosomes (i.e., cells that lack a kinetoplast but contain a nucleus, 0K1N) within 6 h (Fig. 4d). Proportions of dyskinetoplastic trypanosomes increased whereas proportions of cells with one kinetoplast one nucleus (1K1N) and cells with two kinetoplasts and one nucleus (2K1N) decreased during the 30 h treatment (Figs 4d and 5c,d). Compound 1 (200 nM) failed to generate dyskinetoplastic trypanosomes. Instead, 1 increased the fraction of 2K1N cells while decreasing the proportion of 1K1N cells. Furthermore, 1 caused the formation of XK1N trypanosomes containing three or four kinetoplasts and one nucleus (Figs 4c and 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. S6). These observations indicated that 1 inhibits mitosis, but did not affect kinetoplast biogenesis. These differences in the biological effects of EtBr and 1 suggested that the targets of the two compounds are different.

Effects of 30 h treatment with 1 (200 nM) or EtBr (200 nM) on trypanosome DNA content were analyzed (Figs 6 and 7 and Supplementary Figs S7 and S8). For 1, most treated cells contained 4C DNA and a significant fraction (~30%) were polyploid with 8C DNA (Figs 6c and 7a,b and Supplementary Fig. S7). These data indicated that although 1-treated trypanosomes failed mitosis they could, surprisingly, re-enter S-phase of the cell division cycle. Ethidium bromide caused little or no effect on nuclear DNA content compared to the H2O (vehicle) control (Figs 6d and 7c,d and Supplementary Fig. S8).

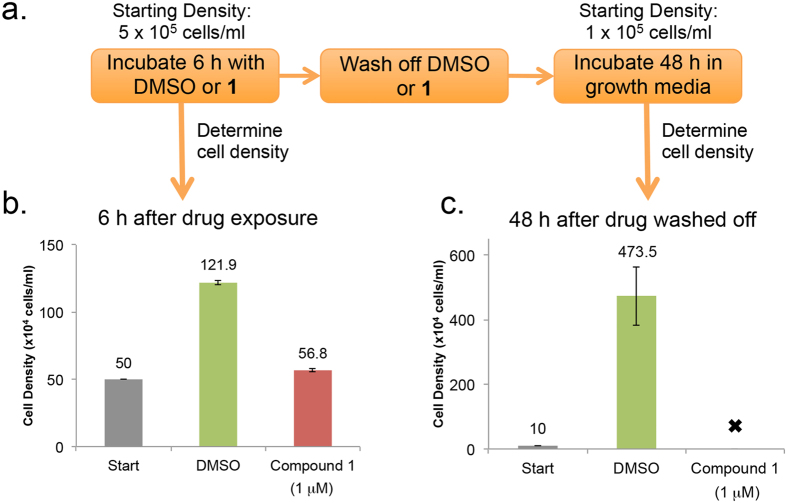

Compound 1 has a “delayed killing” effect on T. brucei

Compound 1 cured trypanosome infection in the mouse model of acute HAT (Fig. 3) whereas 30 h incubation with 200 nM of the drug arrested proliferation of T. brucei in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S4). To explain these data, we hypothesized that exposure of trypanosomes to 1 could lead to “delayed killing” of the cells after removal of drug from culture medium. To test this theory, an experiment was designed to best mimic conditions of detectable parasitemia and reasonable drug exposure in a mouse infection. We used 5 × 105 trypanosomes/mL and 1 μM of compound 1, because the maximum concentration of 1 observed in mouse blood plasma (Cmax) was 2.25 μM after a single oral dose of 30 mg/kg (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Supplementary Table S1). Trypanosomes were treated with 1 (1 μM) for 6 h after which the drug was washed off, trypanosomes were seeded in fresh medium and incubated for 48 h, eight division cycles (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Delayed killing effects of Compound 1 on T. brucei. T. brucei (5 × 105 cells/mL) were treated with 1 (1 μM) or DMSO (0.1% vol/vol) for 6 h.

Cells were washed twice with HMI-9 medium, resuspended at 1 × 105 cells/mL, and cultured for 48 h. Trypanosome densities were determined with a hemocytometer. (a) Flow chart summarizing trypanosome treatment and recovery protocol prior to analysis. (b) Cell density before (“Start”) and after 6 h treatment with DMSO or 1 (1 μM). (c) Cell density after wash and resuspension at 1 × 105 cell/mL (“Start”) and after 48 h incubation in drug-free medium. Mean cell density (values above each bar) ± standard deviation is presented from two independent experiments, four separate biological replicates. “” indicates no cells observed.

Following 6 h compound 1 treatment, wash off, and 48 h incubation in drug-free medium, control cells treated with DMSO proliferated, whereas all 1-treated trypanosomes died (Fig. 8b,c). We concluded that trypanosomes are damaged irreversibly within hours of exposure to 1. Delayed killing effects were restricted to trypanosomes because no such effects on HeLa proliferation were observed under similar experimental conditions (Supplementary Fig. S9).

Discussion

Drugs currently used to treat HAT are in great need of improvement1. Unfortunately, because HAT is a disease of poverty, discovering better drugs against the disease is not suited for expensive research by major pharmaceutical companies38. In this study, we employed a “drug repurposing” strategy7,8 to establish 1 as a lead for anti-trypanosome drug discovery.

By comparing compounds with matching substituents at R3, R4, and/or R5 we observed that replacing cyclopentanones with acetyl groups or other chemical structures at R1 or R2 always reduced the anti-trypanosomal activity of the compound (e.g. compare 5 to CBL0252 to 1, Fig. 1a). Overall, these observations supported the significance of a rotationally-restricted cyclopentanone ring in enhancing anti-trypanosomal features. Cyclopentanone rings provided an electron-withdrawing effect, a hydrogen-bond acceptor, hydrophobicity, and steric restriction. Restraint of the rotation posed by the cyclopentanone ring may have placed the carbonyl group oxygen atom(s) at an ideal orientation for better interaction with the compound’s target(s) of action, when compared to the Class 1 and 2 analogs. Finally, the importance of R1 and R2 on drug potency was illustrated best by CBL0139 and CBL0144 (Fig. 1c). Both compounds contained a nitrogen within the carbazole ring system with no attached substituent, and they were both inactive (GI50 > 10 μM) against T. brucei.

The use of proliferation inhibition assays for hit discovery (Supplementary Fig. S1) is standard for identifying anti-trypanosomal compounds26,30,39. Moreover, there has been a recent emphasis on identifying compounds that kill T. brucei rather than inhibit proliferation40. However, as our work suggests, proliferation inhibition is not always the best indicator of drug efficacy in the mouse model of HAT. For example, 2 and 3 had excellent GI50 values that were less than 10 nM (Table 1). However, 2 and 3 failed to cure T. brucei infection in mice (Fig. 2). Conversely, 1 had relatively less impressive anti-proliferative activity (Table 1). Yet it was 1 that cured a trypanosome infection in mice (Fig. 3). One possible explanation for these results is that varying toxicity of different analogs in mice limits how much drug can be administered to clear the infection without killing the mouse (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Studies investigating the mode of action of our lead compound, 1, revealed that the principal biological effect was inhibition of mitosis (Figs 4 and 5, Supplementary Figs S5 and S6). However, it is not possible to completely exclude other effects contributing to trypanosome death.

Compound 1 treatment led to a build-up of 2K1N and XK1N cells (Fig. 4c) and blocked trypanosome proliferation (Supplementary Fig. S4). The population of cells with 2C DNA was depleted, and instead most trypanosomes had 4C and 8C DNA (Fig. 6c). Together, these data indicated that trypanosomes were unable to execute mitosis, failed to undergo cytokinesis and they re-entered S-phase marked by (i) synthesis of chromosomal DNA, and (ii) production of new kinetoplasts. Consistent with these concepts, detection of trypanosomes with 8C DNA content was concurrent with appearance of XK1N at 18 h (Figs 4c and 6c).

Mitosis inhibition accompanied by ongoing DNA synthesis (both nuclear and mitochondrial) has been reported in bloodstream form (BSF) T. brucei following knockdown of select protein kinases or cyclins41,42. Although compound 1 is a non-genotoxic DNA intercalator in a human cell17, we failed to detect it in trypanosome nuclei using the published conditions. However, the ability to inhibit mitosis and not DNA replication argues against compound 1 principally acting as a DNA intercalator in T. brucei. Instead, compound 1 could target proteins. Compound 1 is a carbazole, some of which bind proteins12,16,17,18,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50. So it is possible that compound 1 has a protein target in trypanosomes.

Three protein kinases (Cdc-2 related kinase 3 (CRK3), Aurora kinase 1 (AUK1) and tousled-like kinase 1 (TLK1)) are of interest as possible targets of 1 because they regulate both nuclear DNA replication and mitosis. Knockdown of CRK351, AUK152 or TLK153 in bloodstream T. brucei results in build-up of 2K1N cells with 4C DNA content. Most strikingly, sustained knockdown of AUK1 led to an accumulation of trypanosomes with 8C DNA content, a single enlarged nucleus, and multiple kinetoplasts similar to the XK1N trypanosomes observed after 1 treatment (Supplementary Fig. S6). CRK3 and TLK1 knockdown also produced an XK1N population, however, effects on DNA content above 4C were not reported.

Mitotic arrest preceding overreplication of DNA has been observed in select vertebrate cells either as a natural process (i.e., differentiation) or induced by drug treatment. In (i) “mitotic slippage” or (ii) endoreplication, human glioma cells treated with nocodazole54, or megakaryocytes undergoing endoreplication55,56,57,58, arrest at mitosis but continue to synthesize DNA.

In summary, we have found that the carbazole compound 1 is an orally bioavailable lead for anti-trypanosome drug discovery, and established its mode of action: it blocks mitosis but allows licensing of chromosomal and kinetoplast DNA replication. Carbazoles such as carprofen and other carbazole derivatives are being evaluated as leads for drugs to treat human neurodegenerative disorders12,13,14,15,16. Additionally, some carbazole derivatives are active against other protozoan parasites, such as Leishmania donovani59, and Plasmodium falciparum60,61. Thus, carbazoles are a promising chemical scaffold for “repurposing” in an effort to discover new and better anti-trypanosomal drugs.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Thomas, S. M. et al. Discovery of a Carbazole-Derived Lead Drug for Human African Trypanosomiasis. Sci. Rep. 6, 32083; doi: 10.1038/srep32083 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alex Adjei (Mayo Clinic) who initiated the collaboration between the Mensa-Wilmot laboratory and Cleveland BioLabs, Inc. We thank Julie Nelson (University of Georgia, UGA) and Justin Wiedeman (UGA) for invaluable technical support for data collection/analysis. We thank Paul Guyett (UGA) and Catherine Sullenberger (UGA) for helpful discussion and advice. Incuron, LLC (Moscow, Russian Federation) performed the pharmacokinetic analysis. Work in the Mensa-Wilmot lab was supported by grant R21AI098998 from the National Institute of Health. Dedicated to the memory of Martin John Rogers (1960–2014). John inspired drug discovery in academia through his enthusiasm and commitment to excellence as a program officer for Tropical Diseases at NIAID (National Institutes of Health). John, you are missed greatly: we will continue your legacy and make you proud.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: S.M.T., A.P. and K.M.-W. Performed the experiments: S.M.T. Analyzed the data: S.M.T., M.P., A.P. and K.M.-W. Wrote the paper: S.M.T., M.P. and K.M.-W.

References

- WHO. Control and surveillance of human African trypanosomiasis. WHO Technical Report Series 984, 1–237 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun R., Blum J., Chappuis F. & Burri C. Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet 375, 148–159, 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60829-1 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser M. et al. Antitrypanosomal activity of fexinidazole, a new oral nitroimidazole drug candidate for treatment of sleeping sickness. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55, 5602–5608, 10.1128/aac.00246-11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs R. T. et al. SCYX-7158, an orally-active benzoxaborole for the treatment of stage 2 human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5, e1151, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001151 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannin J. & Cattand P. Treatment and control of human African trypanosomiasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 17, 565–571 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser P. et al. Antiparasitic agents: new drugs on the horizon. Curr Opin Pharmacol 12, 562–566, 10.1016/j.coph.2012.05.001 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb M. H. et al. Protein farnesyl and N-myristoyl transferases: piggy-back medicinal chemistry targets for the development of antitrypanosomatid and antimalarial therapeutics. Mol Biochem Parasitol 126, 155–163 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburn T. T. & Thor K. B. Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3, 673–683, 10.1038/nrd1468 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera R., Thomas S. M. & Mensa-Wilmot K. New Chemical Scaffolds for Human African Trypanosomiasis Lead Discovery from a Screen of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 2202–2210, 10.1128/aac.01691-13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollastri M. P. & Campbell R. K. Target repurposing for neglected diseases. Future medicinal chemistry 3, 1307–1315, 10.4155/fmc.11.92 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel G. et al. Kinase scaffold repurposing for neglected disease drug discovery: discovery of an efficacious, lapatinib-derived lead compound for trypanosomiasis. J Med Chem 56, 3820–3832, 10.1021/jm400349k (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favia A. D. et al. Identification and characterization of carprofen as a multitarget fatty acid amide hydrolase/cyclooxygenase inhibitor. J Med Chem 55, 8807–8826, 10.1021/jm3011146 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus-Cortes H. et al. Neuroprotective efficacy of aminopropyl carbazoles in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 17010–17015, 10.1073/pnas.1213956109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H. J. et al. Aminopropyl carbazole analogues as potent enhancers of neurogenesis. Bioorg Med Chem 21, 7165–7174, 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.066 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper A. A., McKnight S. L. & Ready J. M. P7C3 and an unbiased approach to drug discovery for neurodegenerative diseases. Chem Soc Rev 43, 6716–6726, 10.1039/c3cs60448a (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saturnino C. et al. N-alkyl carbazole derivatives as new tools for Alzheimer’s disease: preliminary studies. Molecules 19, 9307–9317, 10.3390/molecules19079307 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparian A. V. et al. Curaxins: anticancer compounds that simultaneously suppress NF-kappaB and activate p53 by targeting FACT. Science translational medicine 3, 95–74, 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002530 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter D. R. et al. Therapeutic targeting of the MYC signal by inhibition of histone chaperone FACT in neuroblastoma. Science translational medicine 7, 312ra176, 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab1803 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incuron. A Phase I Trial of CBL0137 in Patients With Metastatic or Unresectable Advanced Solid Neoplasm or Refractory Lymphomas. http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01905228. Date of Access: 2015 Dec 15 (2013).

- Tucker J. et al. Inventors; Cleveland BioLabs, Inc., assignee. Carbazole compounds and therapeutic uses of the compounds. World Patent WO 2010/042445 A1. Apr 15 2010.

- Nwaka S. & Hudson A. Innovative lead discovery strategies for tropical diseases. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 5, 941–955 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirumi H. & Hirumi K. Axenic culture of African trypanosome bloodstream forms. Parasitology Today 10, 80–84, 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90402-2 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal S. et al. Virulence of Trypanosoma brucei strain 427 is not affected by the absence of glycosylphosphatidylinositol phospholipase C. Mol Biochem Parasitol 114, 245–247 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi C. J. et al. Differential susceptibility to DL-alpha-difluoromethylornithine in clinical isolates of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 34, 1183–1188 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar S. et al. Lapatinib-binding protein kinases in the african trypanosome: identification of cellular targets for kinase-directed chemical scaffolds. PloS one 8, e56150, 10.1371/journal.pone.0056150 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky R. & Brun R. In vitro assays to determine drug sensitivities of African trypanosomes: a review. Acta Tropica 54, 279–289, 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90100-p (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber W. & Koella J. C. A comparison of three methods of estimating EC50 in studies of drug resistance of malaria parasites. Acta Tropica 55, 257–261 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaba S. I. & Egorova E. M. In vitro studies of the toxic effects of silver nanoparticles on HeLa and U937 cells. Nanotechnology, science and applications 8, 19–29, 10.2147/nsa.s78134 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwall B. & Johansson A. Preliminary studies on the validity of in vitro measurement of drug toxicity using HeLa cells. I. Comparative in vitro cytotoxicity of 27 drugs. Toxicology letters 5, 299–307 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria J. et al. Drug discovery for human African trypanosomiasis: identification of novel scaffolds by the newly developed HTS SYBR Green assay for Trypanosoma brucei. Journal of biomolecular screening 20, 70–81, 10.1177/1087057114556236 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi C. J. et al. Cure of murine Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense infections with an S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 36, 2736–2740 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nare B. et al. Discovery of Novel Orally Bioavailable Oxaborole 6-Carboxamides That Demonstrate Cure in a Murine Model of Late-Stage Central Nervous System African Trypanosomiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4379–4388, 10.1128/aac.00498-10 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magez S., Radwanska M., Beschin A., Sekikawa K. & De Baetselier P. Tumor necrosis factor alpha is a key mediator in the regulation of experimental Trypanosoma brucei infections. Infect Immun 67, 3128–3132 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouteille B. et al. Effect of megazol on Trypanosoma brucei brucei acute and subacute infections in Swiss mice. Acta Trop 60, 73–80 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthen C., Jensen B. C. & Parsons M. Diverse effects on mitochondrial and nuclear functions elicited by drugs and genetic knockdowns in bloodstream stage Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4, e678, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000678 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwaka S. et al. Advancing drug innovation for neglected diseases-criteria for lead progression. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3, e440, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000440 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy Chowdhury A. et al. The killing of African trypanosomes by ethidium bromide. PLoS Pathog 6, e1001226, 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001226 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMasi J. A., Hansen R. W. & Grabowski H. G. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. Journal of health economics 22, 151–185, 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00126-1 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling T., Mercer L., Don R., Jacobs R. & Nare B. Application of a resazurin-based high-throughput screening assay for the identification and progression of new treatments for human African trypanosomiasis. International journal for parasitology. Drugs and drug resistance 2, 262–270, 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2012.02.002 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rycker M. et al. A Static-Cidal Assay for Trypanosoma brucei to Aid Hit Prioritisation for Progression into Drug Discovery Programmes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6, e1932, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001932 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarton T. C. Cell cycle regulation in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol 153, 1–8, 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.01.017 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Regulation of the cell division cycle in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryotic cell 11, 1180–1190, 10.1128/ec.00145-12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolacci L. et al. A binding site for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in fatty acid amide hydrolase. Journal of the American Chemical Society 135, 22–25, 10.1021/ja308733u (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckler F. M. et al. Targeted rescue of a destabilized mutant of p53 by an in silico screened drug. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 10360–10365, 10.1073/pnas.0805326105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koman I. E. et al. Targeting FACT complex suppresses mammary tumorigenesis in Her2/neu transgenic mice. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa.) 5, 1025–1035, 10.1158/1940-6207.capr-11-0529 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K. et al. Antitumor activity of ER-37328, a novel carbazole topoisomerase II inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther 1, 169–175 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro B. A., Ray S., Jung E., Allred W. T. & Bollag W. B. Putative conventional protein kinase C inhibitor Godecke 6976 [12-(2-cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3.4-c)-carbazole] stimulates transglutaminase activity in primary mouse epidermal keratinocytes. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 302, 352–358 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaill J. B. et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of N-6 substituted analogues of 9-hydroxy-4-phenylpyrrolo[3,4-c]carbazole-1,3(2H,6H)-diones as inhibitors of Wee1 and Chk1 checkpoint kinases. European journal of medicinal chemistry 43, 1276–1296, 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.07.016 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. et al. P7C3 neuroprotective chemicals function by activating the rate-limiting enzyme in NAD salvage. Cell 158, 1324–1334, 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.040 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z. et al. DNA replication is the target for the antibacterial effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Chemistry & biology 21, 481–487, 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.02.009 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu X. & Wang C. C. The involvement of two cdc2-related kinases (CRKs) in Trypanosoma brucei cell cycle regulation and the distinctive stage-specific phenotypes caused by CRK3 depletion. J Biol Chem 279, 20519–20528, 10.1074/jbc.M312862200 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetton N. et al. The cell cycle as a therapeutic target against Trypanosoma brucei: Hesperadin inhibits Aurora kinase-1 and blocks mitotic progression in bloodstream forms. Mol Microbiol 72, 442–458, 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06657.x (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay M. E., Gluenz E., Gull K. & Englund P. T. A new function of Trypanosoma brucei mitochondrial topoisomerase II is to maintain kinetoplast DNA network topology. Mol Microbiol 70, 1465–1476, 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06493.x (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuiki H. et al. Mechanism of hyperploid cell formation induced by microtubule inhibiting drug in glioma cell lines. Oncogene 20, 420–429, 10.1038/sj.onc.1204126 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder L., Larkin J. C. & Schnittger A. Molecular control and function of endoreplication in development and physiology. Trends in plant science 16, 624–634, 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.07.001 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanet J. et al. A mitosis block links active cell cycle with human epidermal differentiation and results in endoreplication. PloS One 5, e15701, 10.1371/journal.pone.0015701 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddis A. E. & Kaushansky K. Megakaryocytes express functional Aurora-B kinase in endomitosis. Blood 104, 1017–1024, 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0419 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitrat N. et al. Endomitosis of human megakaryocytes are due to abortive mitosis. Blood 91, 3711–3723 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendle J. J. et al. Antileishmanial activities of several classes of aromatic dications. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 46, 797–807 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molette J. et al. Identification and optimization of an aminoalcohol-carbazole series with antimalarial properties. ACS medicinal chemistry letters 4, 1037–1041, 10.1021/ml400015f (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erath J. et al. Small-molecule xenomycins inhibit all stages of the Plasmodium life cycle. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59, 1427–1434, 10.1128/aac.04704-14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.