Abstract

The protocol describes the preparation and purification of interstrand DNA-DNA cross-links derived from the reaction of an N4-aminocytidine residue with an abasic site in duplex DNA. The procedures employ inexpensive, commercially-available chemicals and enzymes to carry out post-synthetic modification of commercially-available oligodeoxynucleotides. The yield of cross-linked duplex is typically better than 90%. If purification is required, the cross-linked duplex can be readily separated from single-stranded DNA starting materials by denaturing gel electrophoresis. The resulting covalent hydrazone-based cross-links are stable under physiologically-relevant conditions and may be useful for biophysical studies, structural analyses, DNA repair studies, and materials science applications.

Keywords: DNA cross-link, abasic, oligonucleotide, DNA repair, nanomaterials, click chemistry, hydrazone

INTRODUCTION

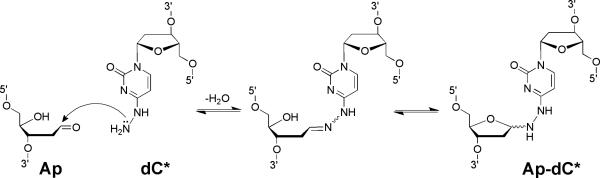

This unit describes methods for the high-yield preparation and purification of DNA duplexes containing interstrand cross-links at well-defined locations. These are simple, bench-top protocols that employ inexpensive, commercially available enzymes and chemicals for the post-synthetic modification of commercially available oligodeoxynucleotides (Gamboa Varela and Gates, 2015). Cross-link formation involves the reaction of an N4-aminocytidine residue (dC*) with an abasic site (Ap) on the opposing strand of a DNA duplex (Figures 1-3). The resulting covalent hydrazone-based cross-links are stable under physiologically-relevant conditions and may be useful for biophysical studies, structural analyses, DNA repair studies, and materials science applications.

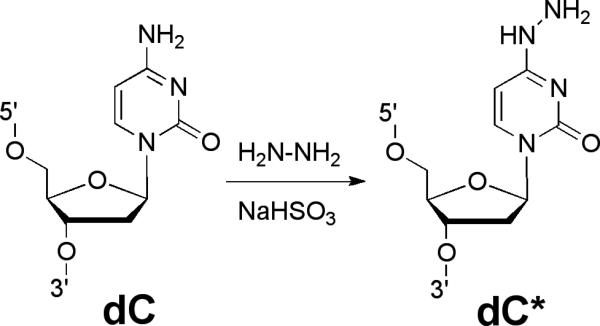

Figure 1.

Conversion of 2’-deoxycytidine (dC) to 4N-amino-2’-deoxycytidine (dC*).

Figure 3.

Formation and possible structures of the Ap-dC* interstrand cross-link.

Basic Protocol 1 describes a procedure for the installation of a dC* residue into oligodeoxynucleotides and Basic Protocol 2 presents the preparation of Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotides and interstrand DNA-DNA cross-link formation in a 5’-32P-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide duplex containing the dC* and Ap residues. The preparation of an unlabeled DNA duplex containing the Ap-dC* cross-link is described in Basic Protocol 3. Basic Protocol 4 reports a method for the purification of the unlabeled duplex containing the Ap-dC* cross-link using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

CAUTION: Chemicals, solvents, and laboratory equipment should be used only after consultation with information provided by the supplier, the relevant material safety data sheet (MSDS), experienced colleagues, and local environmental and health safety personnel.

NOTE: Solvents used in the protocol were HPLC-grade. Solutions are in water unless otherwise noted.

BASIC PROTOCOL 1

PREPARATION OF AN OLIGODEOXYNUCLEOTIDE CONTAINING AN N4-AMINOCYTIDINE RESIDUE (dC*)

This protocol describes the preparation of an oligodeoxynucleotide 2 (Figure 4) containing a single N4-aminocytidine (dC*) residue (Gamboa Varela and Gates, 2015; Gao and Orgel, 1999; Negishi et al., 1987). The procedure involves “post-synthetic modification” of a commercially available oligodeoxynucleotide 1 containing a single dC residue with bisulfite and hydrazine (Figure 1).

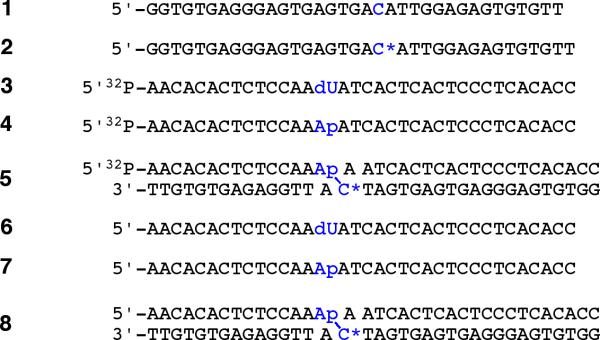

Figure 4.

Sequences used in these Protocols.

Materials

Water (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

1 M Sodium Phosphate buffer, pH 5 (reagent grade, Fisher)

3 M Sodium bisulfite (NaHSO3), freshly prepared (ACS reagent grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

8 M Hydrazine monohydrochloride freshly prepared (reagent grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

0.1 mM Oligodeoxynucleotide 1 (Integrated DNA Technologies) in water

0.5 M Tris base (ACS reagent grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

0.1 M Triethylamine, freshly prepared (TEA, reagent grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

0.001 M Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA, ACS reagent grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

Acetonitrile (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

0.01 M Ammonium acetate (BioXtra grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

8:2 (v:v) Methanol:water (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

1.5 and 2 mL polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes (Eppendorf)

Vortex-mixer (Fisher Vortex Genie 2)

Thermostat-controlled aluminum heating block

C-18 Sep-Pak® cartridges (Waters, 1 cc, 100 mg, cat # WAT023590)

Crushed dry ice

Speed-Vac Concentrator (SC 110, Savant)

Preparation of a dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2

To a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube, add 2.5 μL of water, 2.5 μL of sodium phosphate buffer 1 M stock solution (pH 5), 2.5 μL of a 3 M stock solution in water of sodium bisulfite, and 12.5 μL of a 8 M stock solution of hydrazine monohydrochloride in water.

From a stock solution of oligodeoxynucleotide 1 at a concentration of 0.1 mM transfer 5 μL into the 1.5 mL Eppendorf containing the solution prepared in step 1. This brings the final reaction volume to 25 μL.

Agitate this mixture for 5 s utilizing a vortex-mixer.

Incubate the mixture at 50 °C for 3 h in a thermostat-controlled heating block.

-

Approximately 5 min before the reaction is completed; the Tris-EDTA-TEA (TET) buffer needs to be prepared.

In a 2 mL Eppendorf tube, add 300 μL of water, 100 μL of a 0.5 M stock solution of Tris base, 50 μL of a 0.1 M stock solution of TEA in water, and 50 μL of a 0.001 M stock solution of EDTA. This is the TET buffer (pH ~10).

It is important to freshly prepare the TEA stock solution as its decomposition in solution may decrease the yield of dC*. The Tris base and EDTA stock solutions can be stored at room temperature for at least 3 months.

When the incubation described in step 4 is complete, add 250 μL (10 volumes) of TET buffer to the 1.5 mL Eppendorf reaction tube and mix using a vortex-mixer.

Desalt the oligodeoxynucleotide using a C-18 Sep-Pak® column (1 cc, 100 mg, cat #WAT023590).

-

The C-18 Sep-Pak® column is prepared with the following method:

- Add 1 mL of acetonitrile to the column and completely elute the solvent from the column (into a waste container) by pushing air through it with a 1 mL syringe.

- Add 1 mL of water and similarly elute to waste.

- Add 300 μL of 0.01 M sodium acetate solution in water and elute to waste.

- Add the reaction mixture (275 μL) and elute to waste.

- Add 1 mL of water and elute to waste. Repeat this two more times. This washes salts from the oligodeoxynucleotide.

- Add 1 mL of 8:2 MeOH:water solution and elute the solution into a 2 mL Eppendorf tube. This solution contains the oligodeoxynucleotide.

It is important that the sample is properly desalted because salt may affect the yield of the cross-linking reaction. In our hands, C-18 Sep-Pak® is the best desalting method for this purpose. Ethanol precipitation or G-25 Sephadex spin columns do not desalt the sample as thoroughly.

Place the 2 mL Eppendorf tube in crushed dry ice for 2-3 min with the cap opened.

Dry the sample in a Speed-vac concentrator for approximately 2 h at 37 °C.

The resulting dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2 can be used immediately or stored dry at −20 °C for up to 16 h.

When ready to use the dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2, resuspend in 250 μL of water to achieve a stock solution of approximately 1 μM for the 5’-32P-labeled cross-linking reaction (Basic Protocol 2) or 32.5 μL of water to achieve a stock solution of approximately 6 μM for the unlabeled cross-linking reaction (Basic Protocol 3).

BASIC PROTOCOL 2

PREPARATION OF A 5’-32P-LABELED OLIGODEOXYNUCLEOTIDE DUPLEX (5) CONTAINING THE Ap-dC* INTERSTRAND DNA-DNA CROSS-LINK

This protocol describes conversion of a 5’-32P-labeled dU-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 3 into the corresponding Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 4, followed by hybridization with the dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2 and formation of the cross-linked duplex 5 (Figures 2 and 3).

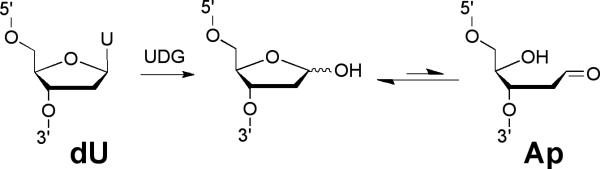

Figure 2.

Conversion of 2’-deoxyuridine (dU) to an abasic site (Ap).

Materials

0.1 mM Oligodeoxynucleotide 3 (Integrated DNA Technologies) in water

Water (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

Uracil-DNA glycosylase reaction buffer 10x (UDG buffer, New England Biolabs)

Uracil-DNA glycosylase enzyme (UDG enzyme, New England Biolabs)

Phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol 25:24:1 (BioUltra for molecular biology, Sigma-Aldrich)

3 M Sodium acetate, pH 5.2 (ACS reagent grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

Absolute ethanol (200 proof, Decon Labs)

8:2 (v:v) Ethanol:water (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

1 M Sodium phosphate buffer, pH 5 (Fisher)

1 M Sodium chloride (NaCl, Fisher)

dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2 (from Basic Protocol 1)

1.5-mL Eppendorf tube

Vortex-mixer (Fisher Vortex Genie 2)

Thermostat-controlled oven-incubator set at 37 °C

Tabletop centrifuge (5424, Eppendorf)

Crushed dry ice

Tabletop centrifuge in cold room 4 °C (AccuSpin Micro 17, Fisher Scientific)

Speed-Vac concentrator (SC 110, Savant)

Thermostat-controlled heating block

Preparation of the Ap-containing 5’-32P-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide 4

-

The oligodeoxynucleotide 3 is 5’-32P-labeled using standard procedures (Sambrook et al., 1989; see UNIT 10.4).

Note: Follow all standard radiation safety protocols for your laboratory and institution.

Resuspend the 5’- 32P-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide 3 in 50 μL of water (approximately 8 μM)

In a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube add 20 μL of water, 4 μL of UDG buffer, 12 μL of oligodeoxynucleotide 3 (100-200K cpm), and 4 μL of UDG enzyme (20 units/mL final) for a total reaction volume of 40 μL.

Mix the reaction using a vortex-mixer for 10 s.

Incubate at 37 °C for 1 h.

Add 40 μL of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol and vortex for 10 s.

Centrifuge at 21130 × g for 3 min (Tabletop microcentrifuge).

Transfer the aqueous (top) layer to a new 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube. Proceed to ethanol precipitation and wash (steps 9-17) (Sambrook et al., 1989).

Add 4 μL of a 3 M stock solution of sodium acetate, pH 5.2.

Add 200 μL (5 volumes) of cold ethanol and vortex for a few seconds.

Place the 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube in crushed dry ice for 55 min.

Centrifuge at 17000 × g at 4 °C for 45 min (tabletop centrifuge).

Remove the supernatant.

Add 90 μL of 8:2 EtOH:water to the Eppendorf tube and vortex for a few seconds.

Centrifuge at 17000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min (tabletop centrifuge).

Remove the supernatant.

-

Dry in a Speed-vac concentrator for 3 min at room temperature (23 °C).

Do not dry the mixture at 37 °C as this can cause cleavage of the oligodeoxynucleotide at the Ap site (Gates, 2009; Gates et al., 2004).

Resuspend the Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 4 in 40 μL of water (approximately 2.5 μM)

Preparation of the cross-linked 5’-32P-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide duplex 5

-

19.

To a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube add 4.5 μL of water, 1 μL of a 1 M stock solution (pH 5) of sodium phosphate buffer, 2 μL of 1 M stock solution of NaCl in water, 10 μL of the dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2, and 2.5 μL of the Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 4 (approximately 30-50K cpm)

-

20.

Mix the solution on a vortex-mixer for 20 s.

-

21.

Incubate in a heating block at 50 °C for 5 min.

-

22.

Remove the aluminum heating block containing the reaction tube from the heating source and allow it to cool to room temperature (over the course of approximately 5 h).

-

23.

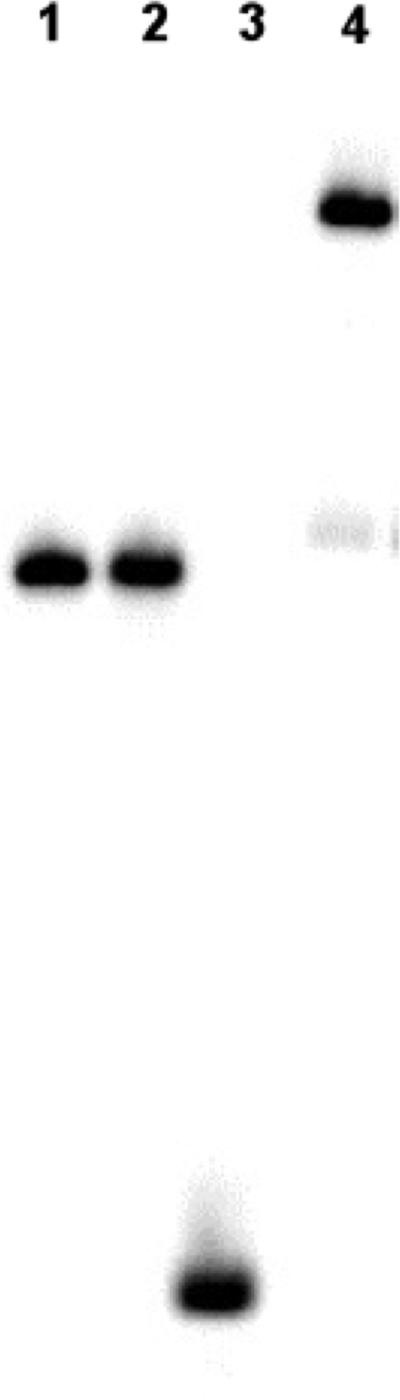

The Ap-dC* cross-link is formed during this incubation typically in yields of 88-95%. For many purposes, the cross-linking reaction mixture may be used without purification, especially because the cross-linked duplex is well resolved from the uncross-linked material on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (Figure 5).

It is important that the incubation time does not exceed 5 h because unreacted Ap-site undergoes cleavage and a low molecular weight cross-link begins to form (see Supporting Information of (Gamboa Varela and Gates, 2015)). The cross-linked DNA duplex 5 can be stored in solution at −20 °C for 1 d. The cross-linked DNA also can be ethanol precipitated and stored dry at −20 °C for up to 3 d. Radiolytic degradation of the DNA can occur if the 5’-32P-labeled material is stored for long periods of time.

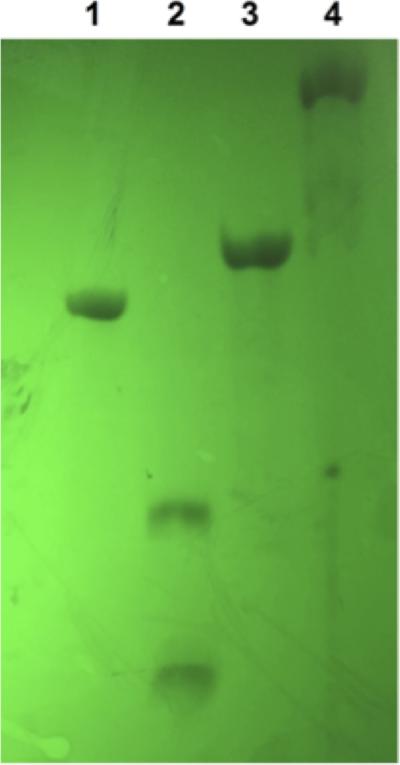

Figure 5.

Formation of the dC*-Ap cross-linked duplex 5. Oligodeoxynucleotides 2 and 4 were incubated in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 5) containing NaCl (100 mM) at 50 °C for 5 min then cooled to room temperature over the course of 5 h. The samples were then mixed with formamide loading buffer the DNA fragments separated on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (0.4 mm thick). The labeled fragments in the gel were visualized by phosphorimager analysis. Lane 1: size marker consisting of the 32P-labeled dU-containing oligonucleotide 3. Lane 2: the Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 4. Lane 3: the Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide treated with piperidine to induce strand cleavage (1 M, 95 °C, 30 min). Lane 4: generation of cross-linked duplex 5 from the complementary oligodeoxynucleotides 2 + 4.

BASIC PROTOCOL 3

PREPARATION OF AN UNLABELED DNA DUPLEX CONTAINING THE INTERSTRAND Ap-dC* CROSS-LINK

Some applications may require the preparation of larger quantities of cross-linked duplexes that do not bear the 5’-32P-label present in Basic Protocol 2. Accordingly, the Protocol below describes preparation of an unlabeled DNA duplex 8 containing the interstrand Ap-dC* cross-link, prepared by hybridization of the Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 7 with the dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2.

Materials

0.1 mM Oligodeoxynucleotide 6 (Integrated DNA Technologies) in water

Water (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

Uracil-DNA glycosylase “10x” reaction buffer (UDG buffer, New England Biolabs)

Uracil-DNA glycosylase enzyme (UDG enzyme, New England Biolabs)

Phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol 25:24:1 (BioUltra for molecular biology, Sigma-Aldrich)

3 M Sodium acetate, pH 5.2 (Sigma-Aldrich)

Absolute ethanol (200 proof, Decon Labs)

8:2 (v:v) Ethanol:water

1 M Sodium phosphate buffer, pH 5 (Fisher)

1 M Sodium chloride (NaCl, Fisher)

dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2 (from Basic Protocol 1)

1.5 mL Eppendorf tube

Vortex-mixer (Fisher Vortex Genie 2)

Thermostat-controlled oven-incubator set at 37 °C

Tabletop centrifuge (5424, Eppendorf)

Tabletop centrifuge in cold room 4 °C (AccuSpin Micro 17, Fisher Scientific)

Speed-vac Concentrator (SC 110, Savant)

Thermostat-controlled heating block

Preparation of the Ap site-containing unlabeled oligodeoxynucleotide 7

In a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube add 10 μL of oligodeoxynucleotide 6 (a 0.1 mM stock solution in water), 4 μL of UDG buffer, 21 μL of water, and 5 μL of UDG enzyme (25 units).

Mix using a vortex-mixer for 30 s.

Incubate at 37 °C for 1 h.

Add 40 μL of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol and vortex for a few seconds.

Centrifuge at 21130 × g for 3 min (tabletop centrifuge).

Remove the aqueous layer and ethanol precipitate as described in Basic Protocol 2, steps 9-16).

Dry the Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 7 in a Speed-vac concentrator for 2-3 min at room temperature (23 °C).

Preparation of the cross-linked duplex 8

Add 10 μL of water to the freshly prepared Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 7.

Add to the Eppendorf tube containing the Ap-oligodeoxynucleotide 7, 5 μL of the 1 M stock solution of NaCl and 2.5 μL of 1 M sodium phosphate buffer.

Resuspend the dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2 in 32.5 μL of water and vortex vigorously for 30 s.

Transfer the dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide 2 to the Eppendorf tube containing the Ap-oligodeoxynucleotide.

Incubate in a thermostat-controlled heating block at 50 °C for 5 min.

Remove the aluminum heating block containing the reaction tube from the heating source and allow it to cool to room temperature (over the course of approximately 5 h).

The cross-linked DNA can be ethanol precipitated (see Basic Protocol 2, steps 9-16) and stored dry at −20 °C until purification.

BASIC PROTOCOL 4

PURIFICATION CROSS-LINKED DUPLEX 8 USING PAGE

This protocol describes the purification of the cross-linked duplex 8 via denaturing PAGE. Basic procedures for gel electrophoresis have been summarized previously (Sambrook et al., 1989; see UNIT 10.4).

The procedure described here is for the purification of approximately 1 nmol of cross-link 8. The procedure can be utilized for reactions up to 20 nmol of cross-link.

Caution: Gel electrophoresis involves the use of a high voltage power source. Use a gel apparatus with proper safety designs after receiving proper safety training.

Materials

20 % denaturing polyacrylamide solution (19:1 acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, 8 M urea, Fisher)

N,N,N’,N’-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED, BioReagent, for molecular biology, Sigma-Aldrich)

10% (w/v) Aqueous ammonium persulfate (for molecular biology, for electrophoresis, Sigma-Aldrich)

Tris-borate-EDTA buffer 1X (TBE buffer, BioReagent, for molecular biology, Sigma-Aldrich)

Formamide loading buffer (17.75 M formamide, deionized, Calbiochem), 0.01 M EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich) with bromophenol blue dye (ACS reagent, Sigma-Aldrich))

Elution buffer (0.2 M NaCl, 0.001 M EDTA, pH 8)

Water (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

Acetonitrile (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

0.01 M Ammonium acetate (BioXtra grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

8:2 (v:v) Methanol:water (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich)

Glass gel plates (16 × 19.7 cm) with 2 mm thick spacers and comb

1.5, 2 mL Eppendorf tubes

100 mL beaker and magnetic stir bar

20 mL disposable syringe and needle

Electrophoresis power source (2060-FBS, E-C Apparatus Corporation)

All-Purpose Laboratory Wrap (Saran Wrap, Fisherbrand)

UV lamp and silica gel TLC plate impregnated with UV-254 fluorophore (Sigma-Aldrich)

Disposable razor blade

Glass rod

Vortex-mixer (Fisher Vortex Genie 2)

Centrifuge (5424, Eppendorf)

Poly-Prep® Chromatography column (spin column, Bio-Rad Laboratories)

Clinical centrifuge (spin-bucket, IEC)

C-18 Sep-Pak® cartridges (Waters, 1 cc, 100 mg, cat #WAT023590)

Speed-vac Concentrator (SC 110, Savant)

Gel purification of cross-link 8

Assemble the glass plates for the gel, sealing the sides and bottom to prevent leaking.

In a 100-mL beaker equipped with a magnetic stir bar, pour 40 mL of 20% polyacrylamide solution containing 8 M urea.

Add TEMED (20-25 μL) to the stirred 100 mL beaker from step 1.

Add 200 μL of aqueous ammonium persulfate to the stirred 100 mL beaker from step 2.

Pour the mixture into the gel plate assembly.

Insert a 12-well comb between the plates assembly.

Allow gel polymerization to occur (1.5-2 h).

After polymerization is complete, remove the comb and bottom spacer slowly, and wash out the wells with a solution of 1X TBE using a 20-mL disposable syringe equipped with a disposable needle.

Mount the plate assembly onto the gel stand. Fill top and bottom wells of the gel stand with 1x TBE.

Before loading samples, electrophorese the gel for 30 min at 300 V.

Add 20 μL of formamide loading buffer to the dry cross-link 8 sample.

Vortex and spin down for 10 s.

Wash the gel wells once again with 1 X TBE.

Load the sample onto the wells of the gel.

Rinse the sample tube with 10 μL of formamide loading buffer.

Vortex and spin down for 10 sec.

Load the sample onto the same well as in step 14.

Electrophorese the gel at 300 V.

Disconnect the gel from the power source once the dye has traveled 12-14 cm from the well (approximately 6 h).

Remove the plate assembly from the stand and separate the plates carefully and remove the gel from both plates.

Wrap the gel with plastic Saran wrap and place on top of a large silica gel TLC plate containing UV-254 fluorophore.

-

Illuminate the gel with a handheld UV-254 lamp onto the gel to “UV-shadow” the DNA bands in the gel.(Sambrook et al., 1989)

The DNA bands will appear as purple bands against the light green fluorescence of emitted by the TLC plate. The cross-linked DNA will appear approximately 5-7 cm from the wells (Figure 6).

Minimize the amount of time the DNA is exposed to the handheld UV light. UV light can cause DNA damage.

Cut the band from the gel with a disposable razor blade and transfer the gel slice into a 2 mL Eppendorf tube.

Crush the gel slice with the tip of a glass rod and add 1 mL of elution buffer.

Shake the sample utilizing a vortex mixer for at least 1 h.

Centrifuge the 2 mL Eppendorf tube for 2 min at 21130 × g.

Transfer the liquid supernatant to an assembled spin-column with a 2 mL Eppendorf receiving tube at the bottom.

Spin using a spin-bucket centrifuge for 10 min at level 5.

Desalt the resulting liquid using a C-18 Sep-Pak® column (see Basic Protocol 1, step 8).

Put the eluted solution in crushed dry ice for 2-3 min.

Evaporate to dryness via Speed-vac concentrator at room temperature (approximately 2-3 h).

Figure 6.

Preparative gel purification of duplex 8 containing the Ap-dC* cross-link. Oligonucleotides 6 and 7 were incubated in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 5) containing NaCl (100 mM) at 50 °C for 5 min then cooled to room temperature over the course of 5 h. The samples were mixed with formamide loading buffer and the DNA fragments resolved on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (2 mm thick). The unlabeled fragments in the gel were visualized by UV-shadowing. Lane 1: size marker consisting of the unlabeled dU-containing oligonucleotide 6. Lane 2: the Ap-containing oligonucleotide 7 treated with piperidine (1 M, 95 °C, 30 min) to induce strand cleavage at the Ap site. Lane 3: the dC*-containing oligonucleotide 2. Lane 4: generation of cross-linked duplex 8 from the complementary oligonucleotides 2 + 7.

After this point the cross-link is ready to use in other experiments. The dry cross-link can be stored for at −20 °C long periods of time, the longest we have stored it is 2 months and have not observed significant degradation during this time.

COMMENTARY

Background Information

Interstrand DNA-DNA cross-links are often studied as critical, medicinally-relevant DNA lesions generated by anticancer chemotherapeutic agents such as cis-platin, carboplatin, bendamustine, or chlorambucil (Cheson and Leoni, 2011; Johnson et al., 2014; Povirk and Shuker, 1994; Rajski and Williams, 1998; Schärer, 2005; Zhu et al., 2013). In addition, there is evidence that some as-yet-unidentified endogenous DNA cross-link(s) may drive human aging (Bergstrahl and Sekelsky, 2007; Niedernhofer et al., 2005). Accordingly, there is substantial interest in the structure, occurrence, biochemical processing, and biological properties of interstrand DNA-DNA cross-links. Structural and biochemical studies can benefit from methods for the high yield preparation of structurally well-defined DNA cross-links. In addition, the facile methods for the preparation of interstrand cross-links may facilitate the construction of stable DNA nanostructures in the field of materials science and nanomedicine (Chen and Schuster, 2013; Rajendran et al., 2011).

The reactions of duplex DNA with bifunctional electrophiles such as anticancer cross-linking drugs or mutagenic agents like acrolein occurs with low sequence selectivity (Kohn et al., 1987; Kozekov et al., 2010; Povirk and Shuker, 1994). Furthermore, only a small number (1-3%) of the initial alkylation events go forward to generate interstrand cross-links (Kozekov et al., 2010; Povirk and Shuker, 1994; Rink et al., 1993). As a result, treatment of mixed sequence DNA with these agents typically generates intractable mixtures of cross-linked duplexes in very low yields. This is usually unacceptable from a preparative perspective. Alternatively, elegant syntheses of structurally-defined cross-linked duplexes have been devised (Balkrishnen et al., 1996; Carrette et al., 2013; Gao and Orgel, 1999; Gruppi et al., 2014; Haque et al., 2014; Harwood et al., 2000; Hentshel et al., 2012; Hong et al., 2006; Manoharan et al., 1999; Mukherjee et al., 2014; Nakatani et al., 2002; Nishimoto et al., 2013; Noll et al., 2001; O'Flaherty et al., 2013; Pujari et al., 2014; Schärer, 2005; Tomás-Gamasa et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2013), but many of these multi-step organic reaction sequences may not be practical in many of the biochemical and materials science laboratories with interests in cross-linked DNA. In the work described here, we sought a simple, benchtop procedure for the synthesis of DNA duplexes containing a site-specific interstrand cross-link that employs inexpensive commercially available enzymes, chemicals, and oligodeoxynucleotides. The Protocol for post-synthetic modification of the oligodeoxynucleotides and cross-linking uses procedures and equipment that are common in many laboratories. The cross-linking reaction exploits the facile post-synthetic generation of dC* and Ap in oligodeoxynucleotides (Gao and Orgel, 1999; Lindahl et al., 1977; Negishi et al., 1987; Varshney and van de Sande, 1991) to access one of the original forms of “click chemistry”, hydrazone formation (Kool et al., 2013; Wang and Canary, 2012), and generates high yields of cross-link at a single defined location in a DNA duplex. If purification is desired, the cross-linked material is readily separated from uncross-linked oligodeoxynucleotides using denaturing gel electrophoresis. The general methods described here can also be used for the preparation and isolation of Ap-derived cross-links involving the native nucleobases guanine and adenine (Catalano et al., 2015; Dutta et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2013; Price et al., 2015; Price et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015).

Critical Parameters

In the preparation of the dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide, removal of bisulfite at the end of the procedure is critical, as the cross-link yield will be greatly reduced or hindered completely if residual bisulfite remains during the cross-linking reaction. We find that desalting of dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotides using a C-18 Sep-Pak® cartridge is superior to other methods such as ethanol precipitation and Sephadex G-25 spin columns. Another important consideration is the design of the dC*-containing oligonucleotide. We have designed our oligonucleotides to contain only a single dC residue (and, therefore, only a single dC* residue) in the strand complementary to the Ap-containing oligonucleotide. In an oligonucleotide with multiple dC residues, presumably all would be transformed to dC* upon treatment with bisulfite/hydrazine. We have not explored cross-link formation when other dC* distal residues are present. We suspect that cross-linking would proceed normally in such a setting. It is critical that the Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide is used immediately after it is prepared as it is prone to cleavage, especially in the single-strand form.

Troubleshooting

The Ap-dC* cross-link can be formed in oligodeoxynucleotide duplexes of various lengths. However, the melting temperature of the oligodeoxynucleotides needs to be taken into consideration as shorter strands will need longer incubation times and/or lower incubation temperatures. In general, yields are likely to be compromised if the cross-linking reactions are carried out at or above the melting temperature of the duplex. The melting temperatures of Ap-containing duplexes are substantially lower than that of a fully paired duplex of similar length (Sági et al., 2001; Vesnaver et al., 1989). Use of low temperatures to favor hybridization of short duplexes may slow the cross-linking reactions. For example, formation of the Ap-dC* cross-link required incubation at 4 °C for 4 d to obtain 40% yield in a 12 base pair duplex. The location of the dU residue in the oligodeoxynucleotide also can affect yield of Ap generation by UDG. dU residues near the end of oligodeoxynucleotides are less effective substrates for UDG (Varshney and van de Sande, 1991). The Ap-dC* cross-link in duplex DNA is thermally reversible (Gamboa Varela and Gates, 2015). That is, the cross-link can be broken by heating the duplex to its melting point, but the cross-link is then spontaneously regenerated upon cooling and rehybridization.

Anticipated results

With the protocols provided, cross-linked duplexes can be obtained in yields of 90% or better. If desired, the cross-linked duplexes can be easily purified by gel electrophoresis.

Time considerations

The cross-links can be obtained in one to three days. In approximately 5-6 h, the dC*-containing oligodeoxynucleotide can be obtained and the dried sample stored at −20 °C for 16 h (overnight), then resuspended in water and utilized in the cross-linking reaction. The Ap-containing oligodeoxynucleotide can be prepared from the corresponding dU-containing oligodeoxynucleotide in a few hours. The Ap-oligodeoxynucleotide should be used immediately in the cross-linking reaction. The cross-linking reaction takes approximately 1 h of set-up time and 5 h of incubation. Gel purification of the cross-linked duplex requires approximately 8 h. The gel slices containing the cross-linked duplex can be frozen overnight and extraction of the material from the gel continued on the next day.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health for support of this work (ES021007).

Literature cited

- Balkrishnen B, Leonard NJ, Robinson H, Wang AH-J. Deoxyadenosine and Thymidine Bases Held Proximal and Distal by Means of a Covalently-Linked Dimensional Analog of dA·dT: Intramolecular vs. Intermolecular Hydrogen Bonding. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118(44):10744–10751. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrahl DT, Sekelsky J. Interstrand crosslink repair: can XPF-ERCC1 be let off the hook? Trends in Genetics. 2007;24(2):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrette LLG, Gyssels E, Madder A. DNA interstrand cross-link formation using furan as a masked reactive aldehyde. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem. 2013;54(5.12):5.12.11–15.12.15. doi: 10.1002/0471142700.nc0512s54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano MJ, Liu S, Andersen N, Yang Z, Johnson KM, Price NA, Wang Y, Gates KS. Chemical structure and properties of the interstrand cross-link formed by the reaction of guanine residues with abasic sites in duplex DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3933–3945. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Schuster GB. Structural stabilization of DNA-templated nanostructures: cross-linking with 2,5-bis(2-thienyl)-pyrrole monomers. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:35–40. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26716k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson BD, Leoni L. Bendamustine: Mechanism of action and clinical data. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 9 Supp. 2011;19(8):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Chowdhury G, Gates KS. Interstrand crosslinks generated by abasic sites in duplex DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1852–1853. doi: 10.1021/ja067294u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa Varela J, Gates KS. A Simple, High-Yield Synthesis of DNA Duplexes Containing a Covalent, Thermally-Reversible Interstrand Cross-link At a Defined Location. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 2015;54:7666–7669. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K, Orgel LE. Nucleic acid duplexes incorporating a dissociable covalent base pair. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(26):14837–14842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates KS. An overview of chemical processes that damage cellular DNA: spontaneous hydrolysis, alkylation, and reactions with radicals. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22(11):1747–1760. doi: 10.1021/tx900242k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates KS, Nooner T, Dutta S. Biologically relevant chemical reactions of N7-alkyl-2′-deoxyguanosine adducts in DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17(7):839–856. doi: 10.1021/tx049965c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruppi F, Salyard TLJ, Rizzo CJ. Synthesis of G-N2-(CH2)3-N2-G trimethylene DNA interstrand cross-links. Curr Prot Nucleic Acid Chem. 2014;56(5.14):5.14, 11–15, 14.15. doi: 10.1002/0471142700.nc0514s56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque MM, Sun H, Liu S, Wang Y, Peng X. Photoswitchable formation of a DNA interstrand cross-link by a coumarin-modified oligonucleotide. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 2014;53:7001–7005. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood EA, Hopkins PB, Sigurdsson ST. Chemical synthesis of cross-link lesions found in nitrous acid treated DNA: A general method for the preparation of N2-substituted 2′-deoxyguanosines. J Org Chem. 2000;65:2959–2964. doi: 10.1021/jo991501+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentshel S, Alzeer J, Angelov T, Schärer OD, Luedtke NW. Synthesis of DNA interstrand cross-links using a photocaged nucleobase. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 2012;51:3466–3469. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong IS, Ding H, Greenberg MM. Oxygen independent DNA interstrand cross-link formation by a nucleotide radical. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:485–491. doi: 10.1021/ja0563657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Parsons ZD, Barnes CL, Gates KS. Toward hypoxia-selective DNA-alkylating agents built by grafting nitrogen mustards onto the bioreductively-activated, hypoxia-selective DNA-oxidizing agent 3-amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine 1,4-dioxide (tirapazamine). J Org Chem. 2014;79:7520–7531. doi: 10.1021/jo501252p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Price NE, Wang J, Fekry MI, Dutta S, Seiner DR, Wang Y, Gates KS. On the Formation and Properties of Interstrand DNA-DNA Cross-links Forged by Reaction of an Abasic Site With the Opposing Guanine Residue of 5’-CAp Sequences in Duplex DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1015–1025. doi: 10.1021/ja308119q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn KW, Hartley JA, Mattes WB. Mechanisms of DNA sequence selective alkylation of guanine-N7 positions by nitrogen mustards. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15(24):10531–10549. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.24.10531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool ET, Park D-H, Crisalli P. Fast Hydrazone Reactants: Electronic and Acid/Base Effects Strongly Influence Rate at Biological pH. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(47):17663–17666. doi: 10.1021/ja407407h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozekov ID, Turesky RJ, Alas GR, Harris CM, Harris TM, Rizzo CJ. Formation of deoxyguanosine cross-links from calf thymus DNA treated with acrolein and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:1701–1713. doi: 10.1021/tx100179g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl T, Ljunquist S, Siegert W, Nyberg B, Sperens B. DNA N-glycosidases: properties of uracil-DNA glycosidase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:3286–3294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoharan M, Andrade LK, Cook PD. Site-specific cross-linking of nucleic acids using the abasic site. Org Lett. 1999;1(2):311–314. doi: 10.1021/ol9906209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Guainazzi A, Schärer OD. Synthesis of struturally diverse major groove DNA interstrand crosslinks using three different aldehyde precursors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7429–7435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani K, Yoshida T, Saito I. Photochemistry of benzophenone immobilized in a major groove of DNA: formation of thermally reversible interstrand cross-link. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2118–2119. doi: 10.1021/ja017611r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi K, Kawakami M, Kayasuga K, Odo J, Hayatsu H. An improved synthesis of N4-aminocytidine. Chem Pharm Bull. 1987;35(9):3884–3887. doi: 10.1248/cpb.35.3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedernhofer LJ, Lalai AS, Hoeijmakers JHJ. Fanconi anemia (cross)linked to DNA repair. Cell. 2005;123(Dec 29):1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto A, Jitsuzaki D, Onizuka K, Tnaiguchi Y, Nagatsugi F, Sasaki S. 4-Vinyl-substituted pyrimidine nucleosides exhibit the efficient and selective formation of interstrand cross-links with RNA and duplex DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(13):6774–6781. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll DM, Noronha AM, Miller PS. Synthesis and characterization of DNA duplexes containing an N4-C-ethyl-N4-C interstrand cross-link. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3405–3411. doi: 10.1021/ja003340t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty DK, McManus FP, Noronha AM, Wilds CJ. Synthesis of building blocks and oligonucleotides containing {T}O4-alkylene{T} interstrand cross-links. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem. 2013;55(5.13):5.13, 11–15, 13.19. doi: 10.1002/0471142700.nc0513s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povirk LF, Shuker DE. DNA damage and mutagenesis induced by nitrogen mustards. Mutation Res. 1994;318:205–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price NE, Catalano MJ, Liu S, Wang Y, Gates KS. Chemical and structural characterization of interstrand cross-links formed between abasic sites and adenine residue in duplex DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:3434–3441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price NE, Johnson KM, Wang J, Fekry M,I, Wang Y, Gates KS. Interstrand DNA–DNA Cross-Link Formation Between Adenine Residues and Abasic Sites in Duplex DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3483–3490. doi: 10.1021/ja410969x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujari SS, Leonard P, Seela F. Oligonucleotides with “clickable” sugar residues: synthesis, duplex stability, and terminal versus central interstrand cross-linking of 2′-O-propargylated 2- aminoadenosine with a bifunctional azide. J Org Chem. 2014;79:4423–4437. doi: 10.1021/jo500392j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran A, Endo M, Katsuda Y, Hidaka K, Sugiyama H. Photo-cross-linking-assisted thermal stability of DNA origami structures and its application for higher-temperature self assembly. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14488–14491. doi: 10.1021/ja204546h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajski SR, Williams RM. DNA cross-linking agents as antitumor drugs. Chem Rev. 1998;98:2723–2795. doi: 10.1021/cr9800199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink SM, Solomon MS, Taylor MJ, Rajur SB, McLaughlin LW, Hopkins PB. Covalent structure of a nitrogen mustard-induced DNA interstrand cross-link: an N7-to-N7 linkage of deoxyguanosine residues at the duplex sequence 5′-d(GNC). J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115(7):2551–2557. [Google Scholar]

- Sági J, Guliaev AB, Singer B. 15-mer DNA duplexes containing an abasic site are thermodynamically more stable with adjacent purines than with pyrimidines. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3859–3868. doi: 10.1021/bi0024409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Lab Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schärer OD. DNA interstrand crosslinks: natural and drug-induced DNA adducts that induce unique cellular responses. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:27–32. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás-Gamasa M, Serdjukow S, Su M, Müller M, Carell T. “Post-it” type connected DNA created with a reversible covalent cross-link. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 2014;53:796–800. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney U, van de Sande JH. Specificities and kinetics of uracil excision from uracil-containing DNA oligomers by Escherichia coli uracil DNA glycosylase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4055–4061. doi: 10.1021/bi00230a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesnaver G, Chang C-N, Eisenberg M, Grollman AP, Breslauer KJ. Influence of abasic and anucleosidic sites on the stability, conformation, and melting behavior of a DNA duplex: correlations of thermodynamic and structural data. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3614–3618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Canary JW. Rapid catalyst-free hydrazone ligation: protein-pyridoxal phosphoramides. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012;23:2329–2334. doi: 10.1021/bc300430k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Johnson KM, Price NE, Gates KS. Characterization of interstrand DNA-DNA cross-links derived from abasic sites using bacteriophage φ29 DNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 2015;54:4259–4266. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye M, Guillaume J, Liu Y, Sha R, Wang R, Seeman NC, Canary JW. Site specific inter-strand cross-links of DNA duplexes. Chem Sci. 2013;4:1319–1329. doi: 10.1039/C2SC21775A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, Song L, Lippard SJ. Visualizing inhibition of nucleosome mobility and transcription by cisplatin-DNA interstrand crosslinks in live mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73(14):4451–4460. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]